Brazil’s Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens has been fighting for decades against the privatization of water and for popular control over natural resources.

This article originally appeared in Roarmag.

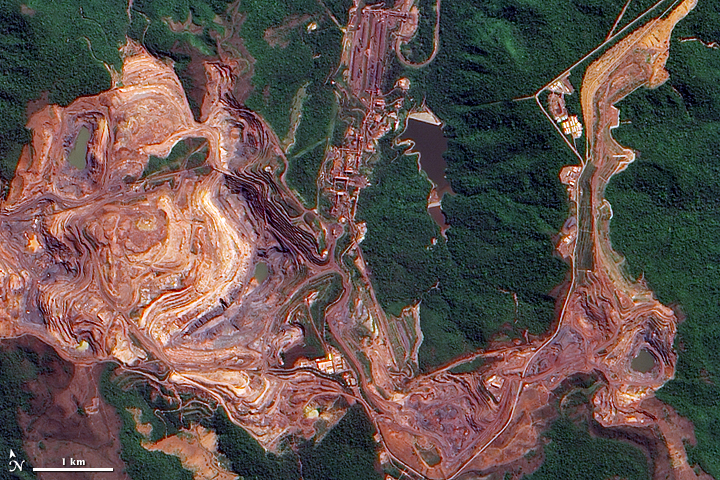

Featured image: Vale open pit iron ore mine, Carajas, Para, 2009

Todos somos atingidos

(“We are all affected”)— Common MAB saying

A person can go a few weeks without food, years without proper shelter, but only a few days without water. Water is fundamental, yet we often forget how much we rely on it. Only 37 percent of the world’s rivers remain free-flowing and numerous hydro dams have destroyed freshwater systems on every continent, threatening food security for millions of people and contributing to the decimation of freshwater non-human life.

Dams and dam failures have catastrophic socio-environmental consequences. In the 20th century alone, large dam projects displaced 40 to 80 million people globally. At the same time, the communities most impacted by dams have been typically excluded from the political decision-making processes affecting their lives.

In Brazil there is an extensive network of mining companies, electric companies and other corporate powers that construct, own and operate dams throughout the country. But for the communities directly affected by hydro dam projects, water and energy are not commodities. Brazil’s Movement of People Affected by Dams (Movimento dos Atingidos por Barragens, or MAB — pronounced “mah-bee”) fights against the displacement and privatization of water, rivers and other natural resources in the belief that everyday people should have sovereignty and control over their own resources.

MAB is a member of La Via Campesina, a transnational social movement representing 300 million people across five continents with over 150 member organizations committed to food sovereignty and climate justice. MAB also works with social movements across Brazil, including the more widely-known Landless Workers Movement (MST), unions and human rights organizations. These alliances speak to the importance of peasant movements and Global South movements in constructing globalizations from below.

MAB focuses its fights on six interconnected areas: human rights, energy, water, dams, the Amazon and international solidarity. The movement organizes for tangible policy and system-level changes and actively creates an alternative to capitalist globalization.

DISASTER CAPITALISM

Just over two years ago, on January 25, 2019, the worst environmental crime in Brazil’s history resulted in the loss of 272 lives. In Córrego do Feijão in Brumadinho, in the state of Minas Gerais, a dam owned by the transnational mining company Vale collapsed. Originally a state-owned company, Vale was privatized in 1997 and since then has made untold billions of dollars mining iron ore and other minerals.

Brazil is the world’s second-largest producer of mineral ores and in 2018 iron ore accounted for 20 percent of all exports from Brazil to the United States. More than 45 percent of Vale’s shareholders are international, including some of the world’s largest investment management companies based in the US such as BlackRock and Capital Group.

The logic of profit has dispossessed people of their sovereignty, their wealth and their water, the very essence of life. The massive dams Vale uses in its mining operations privatize and pollute water used by thousands of people.

When you fly over the state of Minas Gerais, you can see the iron mines as large gaping holes in the ground. Vale and its subsidiaries own and control 175 dams in Brazil, of which 129 are iron ore dams and Minas Gerais accounts for the vast majority of these. Minas Gerais is a region where thousands of people depend upon the water for their livelihood and survival, but the mining leaves the water contaminated. Agriculture and fishing are disrupted or halted, and residents struggle to live without access to potable water.

Exacerbating the problems associated with the privatization and contamination of water for residents, local economy and ecosystems, the dams themselves are vulnerable: the types of dams Vale uses are relatively cheap to build, but also present higher security risks because of their poor structure. When the Brumadinho iron ore mine collapsed, it released a mudflow that swept through a worker cafeteria at lunchtime before wiping out homes, farms and infrastructure. The disaster killed 272 people and an additional 11 people were never found. What made it a crime was that Vale knew something like this could happen. In an earlier assessment, Vale had classified the dam as “two times more likely to fail than the maximum level of risk tolerated under internal guidelines.”

The Associação Estadual de Defesa Ambiental e Social (State Association of Environmental and Social Defense) conducted an assessment and released a report in collaboration with more than 7,000 residents in the regions impacted by the dam collapse. This report shows that depending on the town — the effects of the collapse vary from those communities buried in mud, to those impacted further downstream — 55 to 65 percent of people currently lack employment due to the dam disaster.

Brumadinho is considered one of the worst socio-environmental crimes in the history of Brazil, but it is far from the only one. Five years ago, a dam collapsed in Mariana, killing 20 people; the impacted communities still suffer the effects and are without reparations. On the second anniversary of the Brumadinho collapse, on January 24, 2021, another dam collapsed in Santa Catarina. On March 25, 2021, a dam in Maranhão state, owned by a subsidiary of the Canadian company Equinox Gold, collapsed, polluting the water reservoir of the city of Godofredo Viana, leaving 4,000 people without potable water.

On January 22, 2021, MAB held a virtual international press conference to commemorate two years since the Brumadinho collapse. Jôelisia Feitosa, an atingida (an “affected person”) from Juatuba, one of the communities affected by the dam collapse, described the fallout. People are suffering from skin diseases due to the contaminated water; small farmers cannot continue with their livelihood; people who relied on fishing can no longer do so. As a result, many people have been forced to leave. The lack of potable water has created an emergency. Feitosa said that presently, there are “not conditions for surviving here” anymore. The after-effects of the collapse, compounded by the pandemic, continue to take lives.

There are more than 100,000 atingidos in the region, but people do not know what is going to happen or when emergency aid will come. Further, government negotiations with Vale for “reparations” were conducted without the participation of atingidos. On February 4, 2021, the Brazilian government and Vale reached an accord. Nearly US$7 billion was awarded to the state of Minas Gerais, making it the largest settlement in Brazil’s history, along with murder charges for company officials.

To MAB, however, the accord is illegitimate. It was made under false pretenses, the affected population was not included in the process, and the money, which is not even going to those who are most impacted, does not begin to cover the irreparable and continuing damages. As José Geraldo Martins, a member of the MAB state coordination, said: “[Vale’s] crime destroyed ways of life, dreams, personal projects and the possibility of a future as planned. This leads to people becoming ill, emotionally, mentally, and physically. It aggravates existing health problems and creates new ones.”

As Feitosa put it: “Vale is manipulating the government, manipulating justice.” The accord was reached without the full participation of atingidos, and to make matters worse, Vale decided who qualifies as an atingido based on whether or not people have formal titles to ancestral lands. Vale’s actions create a dangerous precedent that allows corporations to extract, exploit and take human life with impunity. Nearly 300 people died from the 2019 dam collapse, and since then almost 400,000 people have died in Brazil from COVID-19. Yet, during this time, Vale has made a record profit. Neither the dam collapse nor the pandemic has stopped production or profits, even as workers are dying.

FIGHTING BACK: MAB’S STRUGGLE FOR WATER AND LIFE

MAB is committed to continued resistance and will bring the case to the Supreme Court. MAB organizes marches and direct actions and also partners with other movements in activities all across Brazil. They have recently occupied highways and blocked the entrance and exit of trucks to Vale’s facilities. MAB also uses powerful, embodied art and theater called mística that tells a real story and asks participants to put themselves into mindset that “we are all affected.”

MAB emphasizes popular education to understand how historical processes inform present-day struggles. Drawing heavily on Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, they focus on collaborative learning and literacy by making use, for example, of small break-out groups where people take turns reading and discussing short passages. In these projects, there is an intentional effort to fight against interlocking systems of oppression: classism, racism, heterosexism and patriarchy, which are viewed as interlinked with capitalism at the root.

MAB also has a skilled communication team that makes use of online media, including holding frequent talks and panels broadcast via Facebook Live. A recent MAP pamphlet entitled, “Our fight is for life, Enough with Impunity!” details four women important to MAB’s struggle: Dilma, Nicinha, Berta and Marielle. Dilma and Nichina are two women atingidas who were murdered in their fights against dam projects in their communities. Berta was a Honduran environmentalist who also engaged in dam struggles and was murdered. Marielle was a Black, lesbian, socialist city-councilwoman (with Brazil’s Socialism and Liberty Party) in Rio who was murdered in 2018.

For MAB, the struggles of those who have died in their fight for a better world serve as seeds of resistance, a theme further explored in their film “Women Embroidering Resistance.”

For the past two years, MAB has organized events to commemorate the anniversary of the crime committed by Vale in Brumadinho. In 2020, MAB organized a five-day march and international seminar, beginning in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais’ state capital, and ending in Córrego do Feijão with a memorial service. Hundreds of people from around Brazil as well as allies from 17 countries marched through Belo Horizonte, chanting, “Vale killed the people, killed the river, killed the fish!”

Famed liberation theologian Leonardo Boff is a supporter of MAB and spoke at the seminar, decrying that letting people starve is a sin and asserting that “everyone has the right to land; everyone has the right to education; everyone has the right to culture; we all need security and have the right to housing—these are common and basic rights.” He went on: “We don’t get this world by voting — we need participatory democracy.”

MAB commemorated the second anniversary of Brumadinho this past January with various symbolic actions. In one such event, people tossed 11 roses into the water to honor the 11 people who have still not been found, with additional petals to honor the river that has been killed by the mining company. They also organized various virtual actions since the pandemic precluded an in-person convergence like the one held the year before.

JUSTICE THROUGH STRUGGLE AND ORGANIZATION

Less than a month after commemorating Brumadinho in 2020, COVID-19 exploded and the world went into lockdown. Brazil is now one of the hardest-hit countries with the actions and inactions of right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro — from calling COVID-19 a “little flu” to encouraging people to take hydroxychloroquine as a remedy, to defunding the public health system, and cutting back social services — leading to a dire situation.

In April, Brazil recorded over 4,000 COVID-19 deaths in 24 hours, with a death toll second only to the United States. On May 30, the official death toll from COVID-19 was 461,931. Brazil will not soon realize vaccine distribution to the entire population, and people continue to die from lack of oxygen in some regions, prompting an investigation of Bolsonaro and the health minister for mismanagement.

On May 29, 2021, MAB participated in protests with other social movements, unions and the population in general that spanned across 213 cities in Brazil (and 14 cities around the world). The protesters called for Bolsonaro’s impeachment, demanded vaccines and emergency aid for all, and denounced cuts to public health care and education as well as efforts to privatize public services.

In the past five years, the number of Brazilians experiencing hunger has grown to nearly 37 percent. The COVID-19 crisis has only worsened this reality. In August 2020, Bolsonaro vetoed a bill that would have granted emergency assistance to family farmers.

But Brazil’s story is one of resistance, resilience and hope. Efforts bringing together many social movements, unions and other popular organizations have mounted critical mutual aid efforts. MAB is a leader in these efforts, putting together baskets with essential food, hand sanitizer and other essential goods for families in need. The pandemic presents significant challenges, but MAB has continued to resist Bolsonaro’s policies. For example, they are fighting against the defunding of the national public health care system and continuing to organize in communities impacted by dam projects or threatened by new ones.

The fight for the right to water and against the socio-environmental impacts of dams is global. MAB’s struggle is one of resistance against the capitalist system for a world where the rights of people come ahead of profit. As MAB has said: “In 2020, Brazil did not sow rights; on the contrary, the country took lives, especially the lives of women, Black and poor people, all with a lot of violence and impunity.”

MAB’s struggle extends beyond the fight against water privatization. It is part of a global effort to regain the commons of water and fight against the commodification and privatization of life. MAB’s insistence that all forms of oppression are interconnected is also a statement of hope and a catalyst for envisioning a different world. Imagining new possibilities is a prerequisite for creating them.

This year, MAB celebrates 30 years of fighting to guarantee rights and their message is that the only way is to fight and organize: “Justice only with struggle and organization.” In doing so, they are sending a strong message to Vale: they cannot commit a crime like Brumadinho again and profit will not be valued over life.

Caitlin Schroering holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Pittsburgh. She has 16 years of experience in community, political, environmental and labor organizing.

Another article I read this week says there has also been an explosion of mining (most of it illegal) in southern Venezuela — encouraged by the Maduro government, whose oil income is down 90% in the last decade.