by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 19, 2019 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s important to note that, as in the case of protracted popular warfare, Decisive Ecological Warfare is not necessarily a linear progression. In this scenario resisters fall back on previous phases as necessary. After major setbacks, resistance organizations focus on survival and networking as they regroup and prepare for more serious action. Also, resistance movements progress through each of the phases, and then recede in reverse order. That is, if global industrial infrastructure has been successfully disrupted or fragmented (phase IV) resisters return to systems disruption on a local or regional scale (phase III). And if that is successful, resisters move back down to phase II, focusing their efforts on the worst remaining targets.

And provided that humans don’t go extinct, even this scenario will require some people to stay at phase I indefinitely, maintaining a culture of resistance and passing on the basic knowledge and skills necessary to fight back for centuries and millennia.

The progression of Decisive Ecological Warfare could be compared to ecological succession. A few months ago I visited an abandoned quarry, where the topsoil and several layers of bedrock had been stripped and blasted away, leaving a cubic cavity several stories deep in the limestone. But a little bit of gravel or dust had piled up in one corner, and some mosses had taken hold. The mosses were small, but they required very little in the way of water or nutrients (like many of the shoestring affinity groups I’ve worked with). Once the mosses had grown for a few seasons, they retained enough soil for grasses to grow.

Quick to establish, hardy grasses are often among the first species to reinhabit any disturbed land. In much the same way, early resistance organizations are generalists, not specialists. They are robust and rapidly spread and reproduce, either spreading their seeds aboveground or creating underground networks of rhizomes.

The grasses at the quarry built the soil quickly, and soon there was soil for wildflowers and more complex organisms. In much the same way, large numbers of simple resistance organizations help to establish communities of resistance, cultures of resistance, that can give rise to more complex and more effective resistance organizations.

The hypothetical actionists who put this strategy into place are able to intelligently move from one phase to the next: identifying when the correct elements are in place, when resistance networks are sufficiently mobilized and trained, and when external pressures dictate change. In the US Army’s field manual on operations, General Eric Shinseki argues that the rules of strategy “require commanders to master transitions, to be adaptive. Transitions—deployments, the interval between initial operation and sequels, consolidation on the objective, forward passage of lines—sap operational momentum. Mastering transitions is the key to maintaining momentum and winning decisively.”

This is particularly difficult to do when resistance does not have a central command. In this scenario, there is no central means of dispersing operational or tactical orders, or effectively gathering precise information about resistance forces and allies. Shinseki continues: “This places a high premium on readiness—well trained Soldiers; adaptive leaders who understand our doctrine; and versatile, agile, and lethal formations.” People resisting civilization in this scenario are not concerned with “lethality” so much as effectiveness, but the general point stands.

Resistance to civilization is inherently decentralized. That goes double for underground groups which have minimal contact with others. To compensate for the lack of command structure, a general grand strategy in this scenario becomes widely known and accepted. Furthermore, loosely allied groups are ready to take action whenever the strategic situation called for it. These groups are prepared to take advantage of crises like economic collapses.

Under this alternate scenario, underground organizing in small cells has major implications for applying the principles of war. The ideal entity for taking on industrial civilization would have been a large, hierarchal paramilitary network. Such a network could have engaged in the training, discipline, and coordinated action required to implement decisive militant action on a continental scale. However, for practical reasons, a single such network never arises. Similar arrangements in the history of resistance struggle, such as the IRA or various territory-controlling insurgent groups, happened in the absence of the modern surveillance state and in the presence of a well-developed culture of resistance and extensive opposition to the occupier.

Although underground cells can still form out of trusted peers along kinship lines, larger paramilitary networks are more difficult to form in a contemporary anticivilization context. First of all, the proportion of potential recruits in the general population is smaller than in any anticolonial or antioccupation resistance movements in history. So it takes longer and is more difficult to expand existing underground networks. The option used by some resistance groups in Occupied France was to ally and connect existing cells. But this is inherently difficult and dangerous. Any underground group with proper cover would be invisible to another group looking for allies (there are plenty of stories from the end of the war of resisters living across the hall from each other without having realized each other’s affiliation). And in a panopticon, exposing yourself to unproven allies is a risky undertaking.

A more plausible underground arrangement in this scenario is for there to have been a composite of organizations of different sizes, a few larger networks with a number of smaller autonomous cells that aren’t directly connected through command lines. There are indirect connections or communications via cutouts, but those methods are rarely consistent or reliable enough to permit coordinated simultaneous actions on short notice.

Individual cells rarely have the numbers or logistics to engage in multiple simultaneous actions at different locations. That job falls to the paramilitary groups, with cells in multiple locations, who have the command structure and the discipline to properly carry out network disruption. However, autonomous cells maintain readiness to engage in opportunistic action by identifying in advance a selection of appropriate local targets and tactics. Then once a larger simultaneous action happened (causing, say, a blackout), autonomous cells take advantage of the opportunity to undertake their own actions, within a few hours. In this way unrelated cells engage in something close to simultaneous attacks, maximizing their effectiveness. Of course, if decentralized groups frequently stage attacks in the wake of larger “trigger actions,” the corporate media may stop broadcasting news of attacks to avoid triggering more. So, such an approach has its limits, although large-scale effects like national blackouts can’t be suppressed in the news (and in systems disruption, it doesn’t really matter what caused a blackout in the first place, because it’s still an opportunity for further action).

When we look at some struggle or war in history, we have the benefit of hindsight to identify flaws and successes. This is how we judge strategic decisions made in World War II, for example, or any of those who have tried (or not) to intervene in historical holocausts. Perhaps it would be beneficial to imagine some historians in the distant future—assuming humanity survives—looking back on the alternate future just described. Assuming it was generally successful, how might they analyze its strengths and weaknesses?

For these historians, phase IV is controversial, and they know it had been controversial among resisters at the time. Even resisters who agreed with militant actions against industrial infrastructure hesitated when contemplating actions with possible civilian consequences. That comes as no surprise, because members of this resistance were driven by a deep respect and care for all life. The problem is, of course, that members of this group knew that if they failed to stop this culture from killing the planet, there would be far more gruesome civilian consequences.

A related moral conundrum confronted the Allies early in World War II, as discussed by Eric Markusen and David Kopf in their book The Holocaust and Strategic Bombing: Genocide and Total War in the Twentieth Century. Markusen and Kopf write that: “At the beginning of World War II, British bombing policy was rigorously discriminating—even to the point of putting British aircrews at great risk. Only obvious military targets removed from population centers were attacked, and bomber crews were instructed to jettison their bombs over water when weather conditions made target identification questionable. Several factors were cited to explain this policy, including a desire to avoid provoking Germany into retaliating against non-military targets in Britain with its then numerically superior air force.”19

Other factors included concerns about public support, moral considerations in avoiding civilian casualties, the practice of the “Phoney War” (a declared war on Germany with little real combat), and a small air force which required time to build up. The parallels between the actions of the British bombers and the actions of leftist militants from the Weather Underground to the ELF are obvious.

The problem with this British policy was that it simply didn’t work. Germany showed no such moral restraint, and British bombing crews were taking greater risks to attack less valuable targets. By February of 1942, bombing policy changed substantially. In fact, Bomber Command began to deliberately target enemy civilians and civilian morale—particularly that of industrial workers—especially by destroying homes around target factories in order to “dehouse” workers. British strategists believed that in doing so they could sap Germany’s will to fight. In fact, some of the attacks on civilians were intended to “punish” the German populace for supporting Hitler, and some strategists believed that, after sufficient punishment, the population would rise up and depose Hitler to save themselves. Of course, this did not work; it almost never does.

So, this was one of the dilemmas faced by resistance members in this alternate future scenario: while the resistance abhorred the notion of actions affecting civilians—even more than the British did in early World War II—it was clear to them that in an industrial nation the “civilians” and the state are so deeply enmeshed that any impact on one will have some impact on the other.

Historians now believe that Allied reluctance to attack early in the war may have cost many millions of civilian lives. By failing to stop Germany early, they made a prolonged and bloody conflict inevitable. General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command, said as much during his war crimes trial at Nuremburg: “[I]f we did not collapse already in the year 1939 that was due only to the fact that during the Polish campaign, the approximately 110 French and British divisions in the West were held completely inactive against the 23 German divisions.”20

Many military strategists have warned against piecemeal or half measures when only total war will do the job. In his book Grand Strategy: Principles and Practices, John M. Collins argues that timid attacks may strengthen the resolve of the enemy, because they constitute a provocation but don’t significantly damage the physical capability or morale of the occupier. “Destroying the enemy’s resolution to resist is far more important than crippling his material capabilities … studies of cause and effect tend to confirm that violence short of total devastation may amplify rather than erode a people’s determination.”21 Consider, though, that in this 1973 book Collins may underestimate the importance of technological infrastructure and decisive strikes on them. (He advises elsewhere in the book that computers “are of limited utility.”22)

Other strategists have prioritized the material destruction over the adversary’s “will to fight.” Robert Anthony Pape discusses the issue in Bombing to Win, in which he analyzes the effectiveness of strategic bombing in various wars. We can wonder in this alternate future scenario if the resisters attended to Pape’s analysis as they weighed the benefits of phase III (selective actions against particular networks and systems) vs. phase IV (attempting to destroy as much of the industrial infrastructure as possible).

Specifically, Pape argues that targeting an entire economy may be more effective than simply going after individual factories or facilities:

Strategic interdiction can undermine attrition strategies, either by attacking weapons plants or by smashing the industrial base as a whole, which in turn reduces military production. Of the two, attacking weapons plants is the less effective. Given the substitution capacities of modern industrial economies, “war” production is highly fungible over a period of months. Production can be maintained in the short term by running down stockpiles and in the medium term by conservation and substitution of alternative materials or processes. In addition to economic adjustment, states can often make doctrinal adjustments.23

This analysis is poignant, but it also demonstrates a way in which the goals of this alternate scenario’s strategy differed from the goals of strategic bombing in historical conflicts. In the Allied bombing campaign (and in other wars where strategic bombing was used), the strategic bombing coincided with conventional ground, air, and naval battles. Bombing strategists were most concerned with choking off enemy supplies to the battlefield. Strategic bombing alone was not meant to win the war; it was meant to support conventional forces in battle. In contrast, in this alternate future, a significant decrease in industrial production would itself be a great success.

The hypothetical future historians perhaps ask, “Why not simply go after the worst factories, the worst industries, and leave the rest of the economy alone?” Earlier stages of Decisive Ecological Warfare did involve targeting particular factories or industries. However, the resisters knew that the modern industrial economy was so thoroughly integrated that anything short of general economic distruption was unlikely to have lasting effect.

This, too, is shown by historical attempts to disrupt economies. Pape continues, “Even when production of an important weapon system is seriously undermined, tactical and operational adjustments may allow other weapon systems to substitute for it.… As a result, efforts to remove the critical component in war production generally fail.” For example, Pape explains, the Allies carried out a bombing campaign on German aircraft engine plants. But this was not a decisive factor in the struggle for air superiority. Mostly, the Allies defeated the Luftwaffe because they shot down and killed so many of Germany’s best pilots.

Another example of compensation is the Allied bombing of German ball bearing plants. The Allies were able to reduce the German production of ball bearings by about 70 percent. But this did not force a corresponding decrease in German tank forces. The Germans were able to compensate in part by designing equipment that required fewer bearings. They also increased their production of infantry antitank weapons. Early in the war, Germany was able to compensate for the destruction of factories in part because many factories were running only one shift. They were not using their existing industrial capacity to its fullest. By switching to double or triple shifts, they were able to (temporarily) maintain production.

Hence, Pape argues that war economies have no particular point of collapse when faced with increasing attacks, but can adjust incrementally to decreasing supplies. “Modern war economies are not brittle. Although individual plants can be destroyed, the opponent can reduce the effects by dispersing production of important items and stockpiling key raw materials and machinery. Attackers never anticipate all the adjustments and work-arounds defenders can devise, partly because they often rely on analysis of peacetime economies and partly because intelligence of the detailed structure of the target economy is always incomplete.”24 This is a valid caution against overconfidence, but the resisters in this scenario recognized that his argument was not fully applicable to their situation, in part for the reasons we discussed earlier, and in part because of reasons that follow.

Military strategists studying economic and industrial disruption are usually concerned specifically with the production of war materiel and its distribution to enemy armed forces. Modern war economies are economies of total warin which all parts of society are mobilized and engaged in supporting war. So, of course, military leaders can compensate for significant disruption; they can divert materiel or rations from civilian use or enlist civilians and civilian infrastructure for military purposes as they please. This does not mean that overall production is unaffected (far from it), simply that military production does not decline as much as one might expect under a given onslaught.

Resisters in this scenario had a different perspective on compensation measures than military strategists. To understand the contrast, pretend that a military strategist and a militant ecological strategist both want to blow up a fuel pipeline that services a major industrial area. Let’s say the pipeline is destroyed and the fuel supply to industry is drastically cut. Let’s say that the industrial area undertakes a variety of typical measures to compensate—conservation, recycling, efficiency measures, and so on. Let’s say they are able to keep on producing insulation or refrigerators or clothing or whatever it is they make, in diminished numbers and using less fuel. They also extend the lifespan of their existing refrigerators or clothing by repairing them. From the point of view of the military strategist, this attack has been a failure—it has a negligible effect on materiel availability for the military. But from the perspective of the militant ecologist, this is a victory. Ecological damage is reduced, and with very few negative effects on civilians. (Indeed, some effects would be directly beneficial.)

And modern economies in general are brittle. Military economies mobilize resources and production by any means necessary, whether that means printing money or commandeering factories. They are economies of crude necessity. Industrial economies, in contrast, are economies of luxury. They mostly produce things that people don’t need. Industrial capitalism thrives on manufacturing desire as much as on manufacturing products, on selling people disposable plastic garbage, extra cars, and junk food. When capitalist economies hit hard times, as they did in the Great Depression, or as they did in Argentina a decade ago, or as they have in many places in many times, people fall back on necessities, and often on barter systems and webs of mutual aid. They fall back on community and household economies, economies of necessity that are far more resilient than industrial capitalism, and even more robust than war economies.

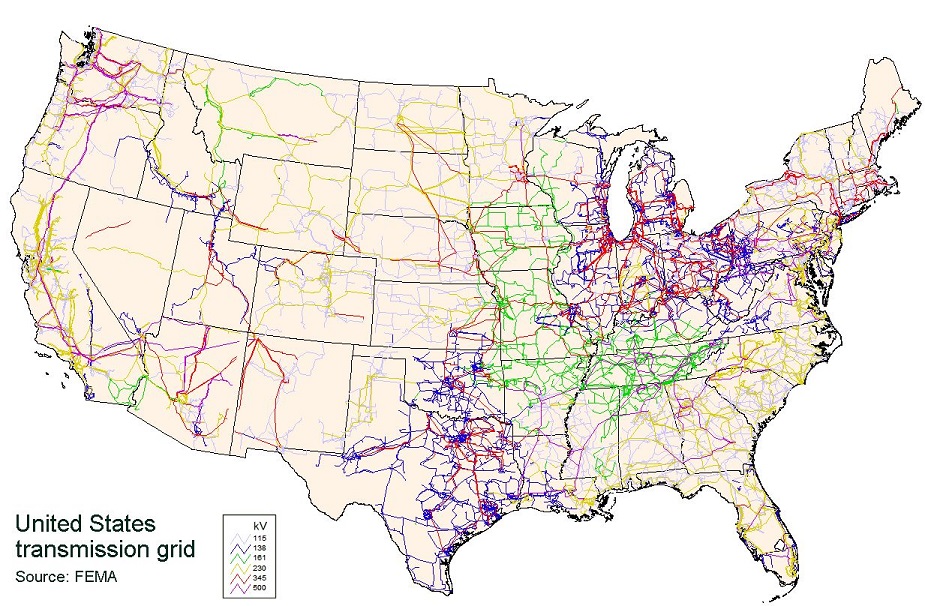

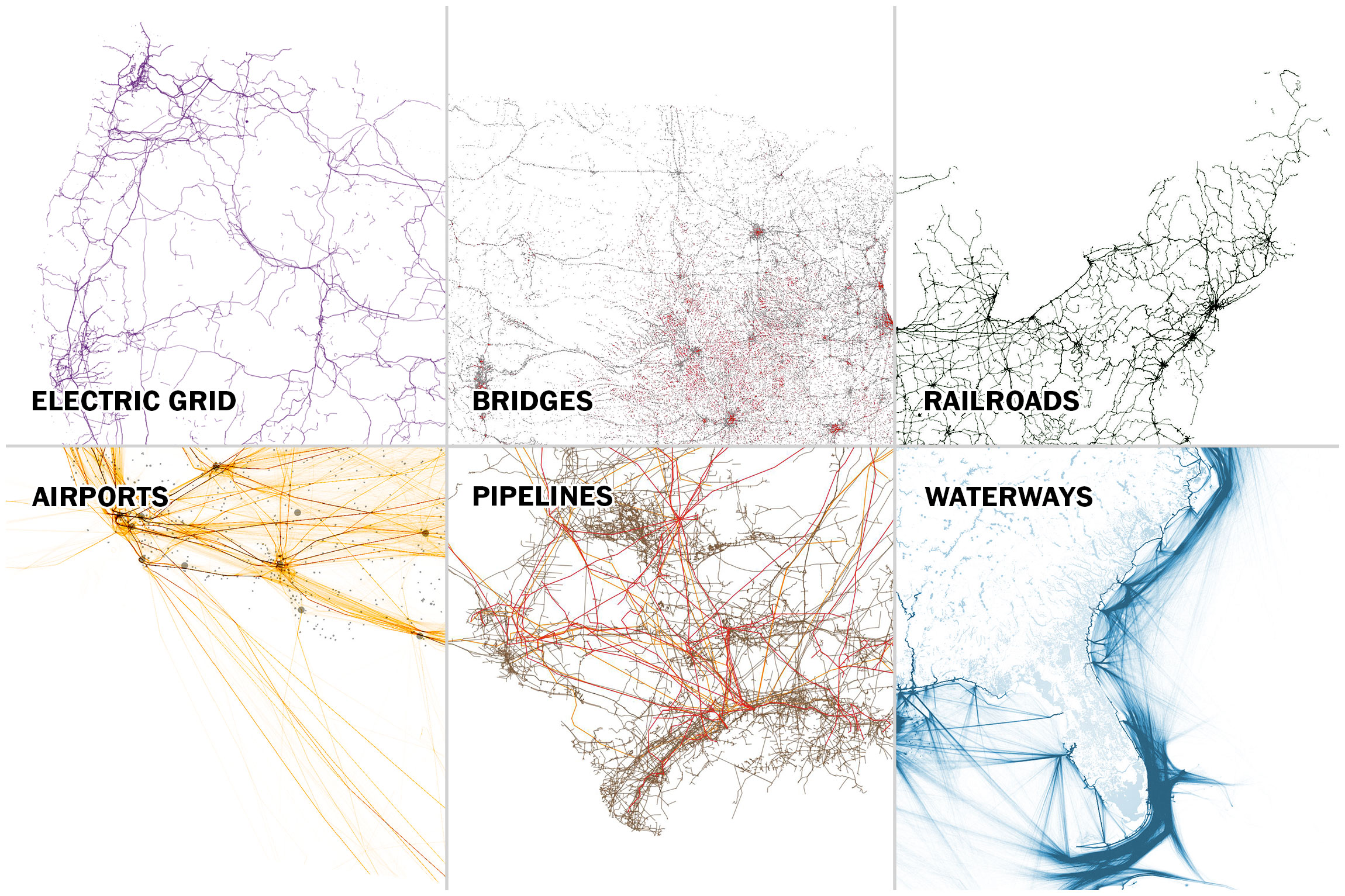

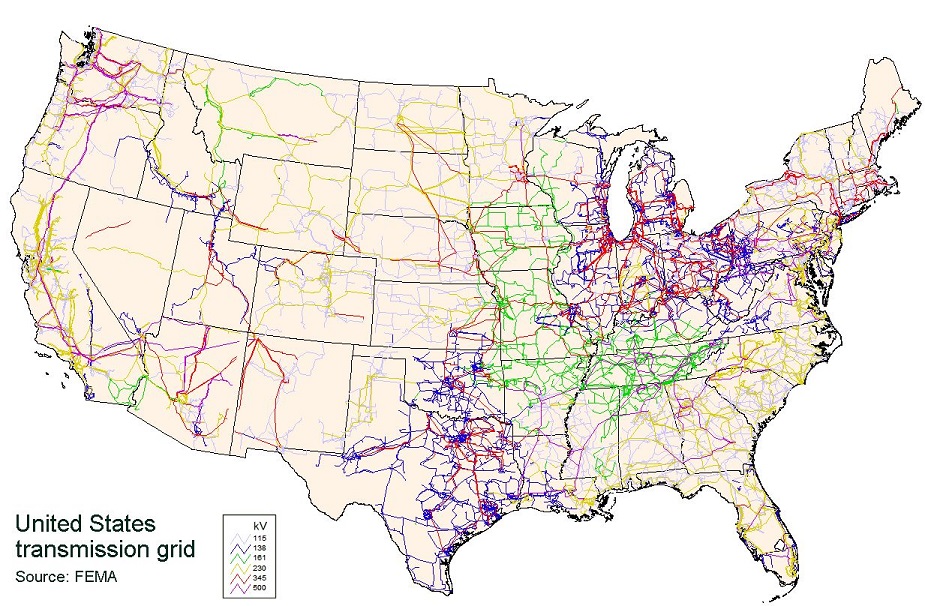

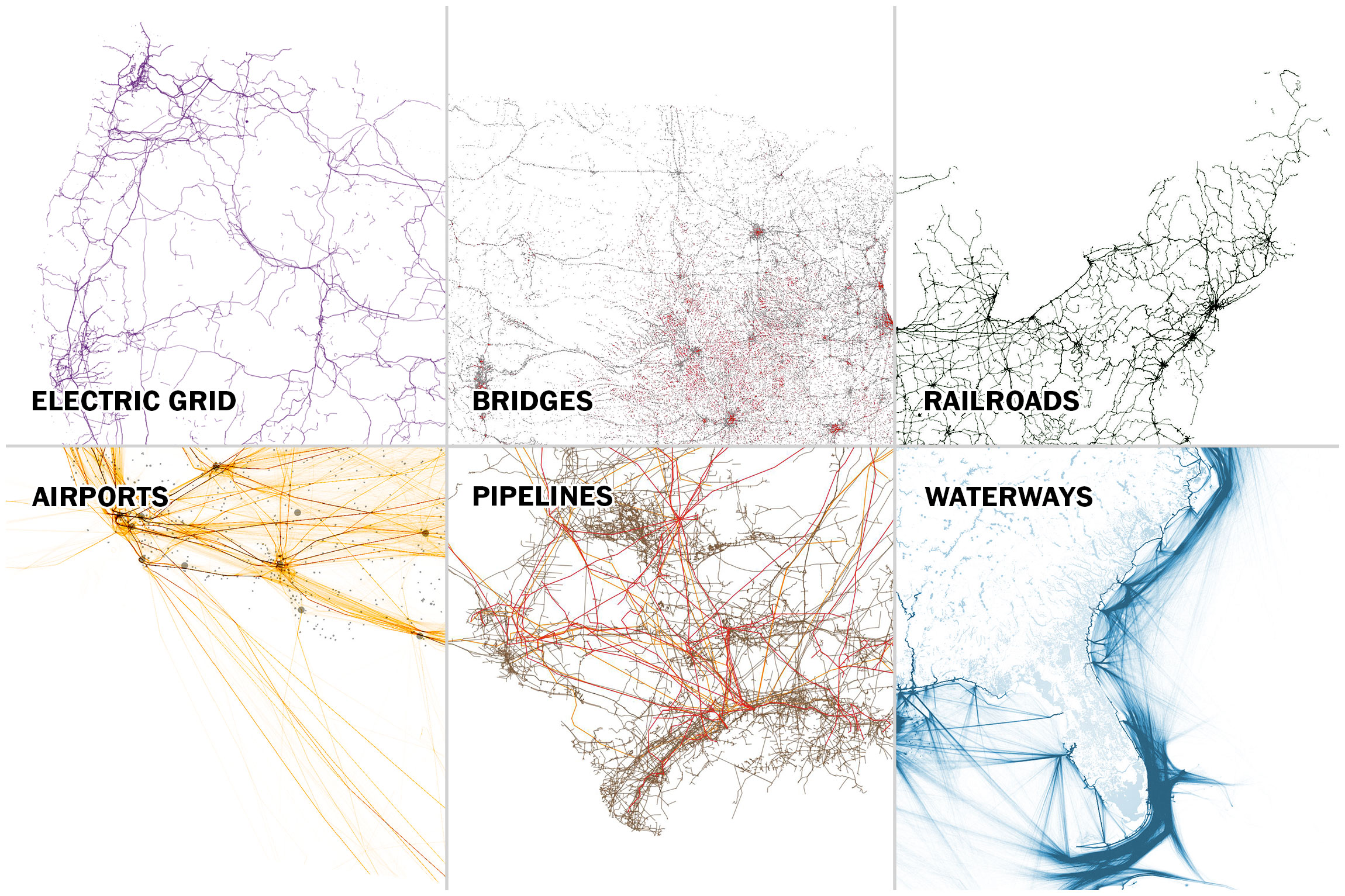

Nonetheless, Pape makes an important point when he argues, “Strategic interdiction is most effective when attacks are against the economy as a whole. The most effective plan is to destroy the transportation network that brings raw materials and primary goods to manufacturing centers and often redistributes subcomponents among various industries. Attacking national electric power grids is not effective because industrial facilities commonly have their own backup power generation. Attacking national oil refineries to reduce backup power generators typically ignores the ability of states to reduce consumption through conservation and rationing.” Pape’s analysis is insightful, but again it’s important to understand the differences between his premises and goals, and the premises and goals of Decisive Ecological Warfare.

The resisters in the DEW scenario had the goals of reducing consumption and reducing industrial activity, so it didn’t matter to them that some industrial facilities had backup generators or that states engaged in conservation and rationing. They believed it was a profound ecological victory to cause factories to run on reduced power or for nationwide oil conservation to have taken place. They remembered that in the whole of its history, the mainstream environmental movement was never even able to stop the growth of fossil fuel consumption. To actually reduce it was unprecedented.25

No matter whether we are talking about some completely hypothetical future situation or the real world right now, the progress of peak oil will also have an effect on the relative importance of different transportation networks. In some areas, the importance of shipping imports will increase because of factors like the local exhaustion of oil. In others, declining international trade and reduced economic activity will make shipping less important. Highway systems may have reduced usage because of increasing fuel costs and decreasing trade. This reduced traffic will leave more spare capacity and make highways less vulnerable to disruption. Rail traffic—a very energy-efficient form of transport—is likely to increase in importance. Furthermore, in many areas, railroads have been removed over a period of several decades, so that remaining lines are even now very crowded and close to maximum capacity.

Back to the alternative future scenario: In most cases, transportation networks were not the best targets. Road transportation (by far the most important form in most countries) is highly redundant. Even rural parts of well-populated areas are crisscrossed by grids of county roads, which are slower than highways, but allow for detours.

In contrast, targeting energy networks was a higher priority to them because the effect of disrupting them was greater. Many electrical grids were already operating near capacity, and were expensive to expand. They became more important as highly portable forms of energy like fossil fuels were partially replaced by less portable forms of energy, specifically electricity generated from coal-burning and nuclear plants, and to a lesser extent by wind and solar energy. This meant that electrical grids carried as much or more energy as they do now, and certainly a larger percentage of all energy consumed. Furthermore, they recognized that energy networks often depend on a few major continent-spanning trunks, which were very vulnerable to disruption.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 29, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Alison mackeyDiscover, based on NASA Earth Observatory image by Robert Simmon, using Suomi NPP VIIRS data provided by Chris Elvidge/NOAA National Geophysical Data Center

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Decisive Ecological Warfare” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

In this alternate future scenario, Decisive Ecological Warfare has four phases that progress from the near future through the fall of industrial civilization. The first phase is Networking & Mobilization. The second phase is Sabotage & Asymmetric Action. The third phase is Systems Disruption. And the fourth and final phase is Decisive Dismantling of Infrastructure.

Each phase has its own objectives, operational approaches, and organizational requirements. There’s no distinct dividing line between the phases, and different regions progress through the phases at different times. These phases emphasize the role of militant resistance networks. The aboveground building of alternatives and revitalization of human communities happen at the same time. But this does not require the same strategic rigor; rebuilding healthy human communities with a subsistence base must simply happen as fast as possible, everywhere, with timetables and methods suited to the region. This scenario’s militant resisters, on the other hand, need to share some grand strategy to succeed.

PHASE I: NETWORKING & MOBILIZATION

Preamble: In phase one, resisters focus on organizing themselves into networks and building cultures of resistance to sustain those networks. Many sympathizers or potential recruits are unfamiliar with serious resistance strategy and action, so efforts are taken to spread that information. But key in this phase is actually forming the above- and underground organizations (or at least nuclei) that will carry out organizational recruitment and decisive action. Security culture and resistance culture are not very well developed at this point, so extra efforts are made to avoid sloppy mistakes that would lead to arrests, and to dissuade informers from gathering or passing on information.

Training of activists is key in this phase, especially through low-risk (but effective) actions. New recruits will become the combatants, cadres, and leaders of later phases. New activists are enculturated into the resistance ethos, and existing activists drop bad or counterproductive habits. This is a time when the resistance movement gets organized and gets serious. People are putting their individual needs and conflicts aside in order to form a movement that can fight to win.

In this phase, isolated people come together to form a vision and strategy for the future, and to establish the nuclei of future organizations. Of course, networking occurs with resistance-oriented organizations that already exist, but most mainstream organizations are not willing to adopt positions of militancy or intransigence with regard to those in power or the crises they face. If possible, they should be encouraged to take positions more in line with the scale of the problems at hand.

This phase is already underway, but a great deal of work remains to be done.

Objectives:

- To build a culture of resistance, with all that entails.

- To build aboveground and underground resistance networks, and to ensure the survival of those networks.

Operations:

- Operations are generally lower-risk actions, so that people can be trained and screened, and support networks put in place. These will fall primarily into the sustaining and shaping categories.

- Maximal recruitment and training is very important at this point. The earlier people are recruited, the more likely they are to be trustworthy and the longer time is available to screen them for their competency for more serious action.

- Communications and propaganda operations are also required for outreach and to spread information about useful tactics and strategies, and on the necessity for organized action.

Organization:

- Most resistance organizations in this scenario are still diffuse networks, but they begin to extend and coalesce. This phase aims to build organization.

PHASE II: SABOTAGE & ASYMMETRIC ACTION

Preamble: In this phase, the resisters might attempt to disrupt or disable particular targets on an opportunistic basis. For the most part, the required underground networks and skills do not yet exist to take on multiple larger targets. Resisters may go after particularly egregious targets—coal-fired power plants or exploitative banks. At this phase, the resistance focus is on practice, probing enemy networks and security, and increasing support while building organizational networks. In this possible future, underground cells do not attempt to provoke overwhelming repression beyond the ability of what their nascent networks can cope with. Furthermore, when serious repression and setbacks do occur, they retreat toward the earlier phase with its emphasis on organization and survival. Indeed, major setbacks probably do happen at this phase, indicating a lack of basic rules and structure and signaling the need to fall back on some of the priorities of the first phase.

The resistance movement in this scenario understands the importance of decisive action. Their emphasis in the first two phases has not been on direct action, but not because they are holding back. It’s because they are working as well as they damned well can, but doing so while putting one foot in front of the other. They know that the planet (and the future) need their action, but understand that it won’t benefit from foolish and hasty action, or from creating problems for which they are not yet prepared. That only leads to a morale whiplash and disappointment. So their movement acts as seriously and swiftly and decisively as it can, but makes sure that it lays the foundation it needs to be truly effective.

The more people join that movement, the harder they work, and the more driven they are, the faster they can progress from one phase to the next.

In this alternate future, aboveground activists in particular take on several important tasks. They push for acceptance and normalization of more militant and radical tactics where appropriate. They vocally support sabotage when it occurs. More moderate advocacy groups use the occurrence of sabotage to criticize those in power for failing to take action on critical issues like climate change (rather than criticizing the saboteurs). They argue that sabotage would not be necessary if civil society would make a reasonable response to social and ecological problems, and use the opportunity and publicity to push solutions to the problems. They do not side with those in power against the saboteurs, but argue that the situation is serious enough to make such action legitimate, even though they have personally chosen a different course.

At this point in the scenario, more radical and grassroots groups continue to establish a community of resistance, but also establish discrete organizations and parallel institutions. These institutions establish themselves and their legitimacy, make community connections, and particularly take steps to found relationships outside of the traditional “activist bubble.” These institutions also focus on emergency and disaster preparedness, and helping people cope with impending collapse.

Simultaneously, aboveground activists organize people for civil disobedience, mass confrontation, and other forms of direct action where appropriate.

Something else begins to happen: aboveground organizations establish coalitions, confederations, and regional networks, knowing that there will be greater obstacles to these later on. These confederations maximize the potential of aboveground organizing by sharing materials, knowledge, skills, learning curricula, and so on. They also plan strategically themselves, engaging in persistent planned campaigns instead of reactive or crisis-to-crisis organizing.

Objectives:

- Identify and engage high-priority individual targets. These targets are chosen by these resisters because they are especially attainable or for other reasons of target selection.

- Give training and real-world experience to cadres necessary to take on bigger targets and systems. Even decisive actions are limited in scope and impact at this phase, although good target selection and timing allows for significant gains.

- These operations also expose weak points in the system, demonstrate the feasibility of material resistance, and inspire other resisters.

- Publically establish the rationale for material resistance and confrontation with power.

- Establish concrete aboveground organizations and parallel institutions.

Operations:

- Limited but increasing decisive operations, combined with growing sustaining operations (to support larger and more logistically demanding organizations) and continued shaping operations.

- In decisive and supporting operations, these hypothetical resisters are cautious and smart. New and unseasoned cadres have a tendency to be overconfident, so to compensate they pick only operations with certain outcomes; they know that in this stage they are still building toward the bigger actions that are yet to come.

Organization:

- Requires underground cells, but benefits from larger underground networks. There is still an emphasis on recruitment at this point. Aboveground networks and movements are proliferating as much as they can, especially since the work to come requires significant lead time for developing skills, communities, and so on.

PHASE III: SYSTEMS DISRUPTION

Preamble: In this phase resisters step up from individual targets to address entire industrial, political, and economic systems. Industrial systems disruption requires underground networks organized in a hierarchal or paramilitary fashion. These larger networks emerge out of the previous phases with the ability to carry out multiple simultaneous actions.

Systems disruption is aimed at identifying key points and bottlenecks in the adversary’s systems (electrical, transport, financial, and so on) and engaging them to collapse those systems or reduce their functionality. This is not a one-shot deal. Industrial systems are big and can be fragile, but they are sprawling rather than monolithic. Repairs are attempted. The resistance members understand that. Effective systems disruption requires planning for continued and coordinated actions over time.

In this scenario, the aboveground doesn’t truly gain traction as long as there is business as usual. On the other hand, as global industrial and economic systems are increasingly disrupted (because of capitalist-induced economic collapse, global climate disasters, peak oil, peak soil, peak water, or for other reasons) support for resilient local communities increases. Failures in the delivery of electricity and manufactured goods increases interest in local food, energy, and the like. These disruptions also make it easier for people to cope with full collapse in the long term—short-term loss, long-term gain, even where humans are concerned.

Dimitry Orlov, a major analyst of the Soviet collapse, explains that the dysfunctional nature of the Soviet system prepared people for its eventual disintegration. In contrast, a smoothly functioning industrial economy causes a false sense of security so that people are unprepared, worsening the impact. “After collapse, you regret not having an unreliable retail segment, with shortages and long bread lines, because then people would have been forced to learn to shift for themselves instead of standing around waiting for somebody to come and feed them.”18

Aboveground organizations and institutions are well-established by this phase of this alternate scenario. They continue to push for reforms, focusing on the urgent need for justice, relocalization, and resilient communities, given that the dominant system is unfair, unreliable, and unstable.

Of course, in this scenario the militant actions that impact daily life provoke a backlash, sometimes from parts of the public, but especially from authoritarians on every level. The aboveground activists are the frontline fighters against authoritarianism. They are the only ones who can mobilize the popular groundswell needed to prevent fascism.

Furthermore, aboveground activists use the disrupted systems as an opportunity to strengthen local communities and parallel institutions. Mainstream people are encouraged to swing their support to participatory local alternatives in the economic, political, and social spheres. When economic turmoil causes unemployment and hyperinflation, people are employed locally for the benefit of their community and the land. In this scenario, as national governments around the world increasingly struggle with crises (like peak oil, food shortages, climate chaos, and so on) and increasingly fail to provide for people, local and directly democratic councils begin to take over administration of basic and emergency services, and people redirect their taxes to those local entities (perhaps as part of a campaign of general noncooperation against those in power). This happens in conjunction with the community emergency response and disaster preparedness measures already undertaken.

In this scenario, whenever those in power try to increase exploitation or authoritarianism, aboveground resisters call for people to withdraw support from those in power, and divert it to local, democratic political bodies. Those parallel institutions can do a better job than those in power. The cross demographic relationships established in previous phases help to keep those local political structures accountable, and to rally support from many communities.

Throughout this phase, strategic efforts are made to augment existing stresses on economic and industrial systems caused by peak oil, financial instability, and related factors. The resisters think of themselves as pushing on a rickety building that’s already starting to lean. Indeed, in this scenario many systems disruptions come from within the system itself, rather than from resisters.

This phase accomplishes significant and decisive gains. Even if the main industrial and economic systems have not completely collapsed, prolonged disruption means a reduction in ecological impact; great news for the planet, and for humanity’s future survival. Even a 50 percent decrease in industrial consumption or greenhouse gas emissions is a massive victory (especially considering that emissions have continued to rise in the face of all environmental activism so far), and that buys resisters—and everyone else—some time.

In the most optimistic parts of this hypothetical scenario, effective resistance induces those in power to negotiate or offer concessions. Once the resistance movement demonstrates the ability to use real strategy and force, it can’t be ignored. Those in power begin to knock down the doors of mainstream activists, begging to negotiate changes that would co-opt the resistance movements’ cause and reduce further actions.

In this version of the future, however, resistance groups truly begin to take the initiative. They understand that for most of the history of civilization, those in power have retained the initiative, forcing resistance groups or colonized people to stay on the defensive, to respond to attacks, to be constantly kept off balance. However, peak oil and systems disruption has caused a series of emergencies for those in power; some caused by organized resistance groups, some caused by civil unrest and shortages, and some caused by the social and ecological consequences of centuries—millennia—of exploitation. For perhaps the first time in history, those in power are globally off balance and occupied by worsening crisis after crisis. This provides a key opportunity for resistance groups, and autonomous cultures and communities, to seize and retain the initiative.

Objectives:

- Target key points of specific industrial and economic systems to disrupt and disable them.

- Effect a measurable decrease in industrial activity and industrial consumption.

- Enable concessions, negotiations, or social changes if applicable.

- Induce the collapse of particular companies, industries, or economic systems.

Operations:

- Mostly decisive and sustaining, but shaping where necessary for systems disruption. Cadres and combatants should be increasingly seasoned at this point, but the onset of decisive and serious action will mean a high attrition rate for resisters. There’s no point in being vague; the members of the resistance in this alternate future who are committed to militant resistance go in expecting that they will either end up dead or in jail. They know that anything better than that was a gift to be won through skill and luck.

Organization:

- Heavy use of underground networks required; operational coordination is a prerequisite for effective systems disruption.

- Recruitment is ongoing at this point; especially to recruit auxiliaries and to cope with losses due to attrition. However, during this phase there are multiple serious attempts at infiltration. The infiltrations are not as successful as they might have been, because underground networks have recruited heavily in previous stages (before large-scale action) to ensure the presence of a trusted group of leaders and cadres who form the backbone of the networks.

- Aboveground organizations are able to mobilize extensively because of various social, political, and material crises.

- At this point, militant resisters become concerned about backlash from people who should be on their side, such as many liberals, especially as those in power put pressure on aboveground activists.

PHASE IV: DECISIVE DISMANTLING OF INFRASTRUCTURE

Preamble: Decisive dismantling of infrastructure goes a step beyond systems disruption. The intent is to permanently dismantle as much of the fossil fuel–based industrial infrastructure as possible. This phase is the last resort; in the most optimistic projection, it would not be necessary: converging crises and infrastructure disruption would combine with vigorous aboveground movements to force those in power to accept social, political, and economic change; reductions in consumption would combine with a genuine and sincere attempt to transition to a sustainable culture.

But this optimistic projection is not probable. It is more likely that those in power (and many everyday people) will cling more to civilization even as it collapses. And likely, they will support authoritarianism if they think it will maintain their privilege and their entitlement.

The key issue—which we’ve come back to again and again—is time. We will soon reach (if we haven’t already reached) the trigger point of irreversible runaway global warming. The systems disruption phase of this hypothetical scenario offers selectivity. Disruptions in this scenario are engineered in a way that shifts the impact toward industry and attempts to minimize impacts on civilians. But industrial systems are heavily integrated with civilian infrastructure. If selective disruption doesn’t work soon enough, some resisters may conclude that all-out disruption is required to stop the planet from burning to a cinder.

The difference between phases III and IV of this scenario may appear subtle, since they both involve, on an operational level, coordinated actions to disrupt industrial systems on a large scale. But phase III requires some time to work—to weaken the system, to mobilize people and organizations, to build on a series of disruptive actions. Phase III also gives “fair warning” for regular people to prepare. Furthermore, phase III gives time for the resistance to develop itself logistically and organizationally, which is required to proceed to phase IV. The difference between the two phases is capacity and restraint. For resisters in this scenario to proceed from phase III to phase IV, they need two things: the organizational capacity to take on the scope of action required under phase IV, and the certainty that there is no longer any point in waiting for societal reforms to succeed on their own timetable.

In this scenario, both of those phases save lives, human and nonhuman alike. But if large-scale aboveground mobilization does not happen once collapse is underway, phase IV becomes the most effective way to save lives.

Imagine that you are riding in a streetcar through a city crowded with pedestrians. Inside the streetcar are the civilized humans, and outside is all the nonhuman life on the planet, and the humans who are not civilized, or who do not benefit from civilization, or who have yet to be born. Needless to say, those outside far outnumber the few of you inside the streetcar. But the driver of the streetcar is in a hurry, and is accelerating as fast as he can, plowing through the crowds, maiming and killing pedestrians en masse. Most of your fellow passengers don’t seem to particularly care; they’ve got somewhere to go, and they’re glad to be making progress regardless of the cost.

Some of the passengers seem upset by the situation. If the driver keeps accelerating, they observe, it’s possible that the streetcar will crash and the passengers will be injured. Not to worry, one man tells them. His calculations show that the bodies piling up in front of the streetcar will eventually slow the vehicle and cause it to safely come to a halt. Any intervention by the passengers would be reckless, and would surely provoke a reprimand from the driver. Worse, a troublesome passenger might be kicked off the streetcar and later run over by it.

You, unlike most passengers, are more concerned by the constant carnage outside than by the future safety of the streetcar passengers. And you know you have to do something. You could try to jump out the window and escape, but then the streetcar would plow on through the crowd, and you would lose any chance to intervene. So you decide to try to sabotage the streetcar from the inside, to cut the electrical wires, or pull up the flooring and activate the brakes by hand, or derail it, or do whatever you can.

As soon as the other passengers realize what you are doing, they’ll try to stop you, and maybe kill you. You have to decide whether you are going to stop the streetcar slowly or speedily. The streetcar is racing along so quickly now that if you stop it suddenly, it may fling the passengers against the seats in front of them or down the aisle. It may kill some of them. But if you stop it slowly, who knows how many innocent people will be struck by the streetcar while it is decelerating? And if you just slow it down, the driver may be able to repair the damage and get the streetcar going again.

So what do you do? If you choose to stop the streetcar as quickly as possible, then you have made the same choice as those who would implement phase IV. You’ve made the decision that stopping the destruction as rapidly as possible is more important than any particular program of reform. Of course, even in stopping the destruction as rapidly as possible, you can still take measures to reduce casualties on board the streetcar. You can tell people to sit down or buckle up or brace themselves for impact. Whether they will listen to you is another story, but that’s their responsibility, not yours.

It’s important to not misinterpret the point of phase IV of this alternate future scenario. The point is not to cause human casualties. The point is to stop the destruction of the planet. The enemy is not the civilian population—or any population at all—but a sociopathological sociopolitical and economic system. Ecological destruction on this planet is primarily caused by industry and capitalism; the issue of population is tertiary at best. The point of collapsing industrial infrastructure in this scenario is not to harm humans any more than the point of stopping the streetcar is to harm the passengers. The point is to reduce the damage as quickly as possible, and in doing so to account for the harm the dominant culture is doing to all living creatures, past and future.

This is not an easy phase for the abovegrounders. Part of their job in this scenario is also to help demolish infrastructure, but they are mostly demolishing exploitative political and economic infrastructure, not physical infrastructure. In general, they continue to do what they did in the previous phase, but on a larger scale and for the long term. Public support is directed to local, democratic, and just political and economic systems. Efforts are undertaken to deal with emergencies and cope with the nastier parts of collapse.

Objectives:

- Dismantle the critical physical infrastructure required for industrial civilization to function.

- Induce widespread industrial collapse, beyond any economic or political systems.

- Use continuing and coordinated actions to hamper repairs and replacement.

Operations:

- Focus almost exclusively on decisive and sustaining operations.

Organization:

- Requires well-developed militant underground networks.

Continue reading at Implementing Decisive Ecological Warfare

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 25, 2018 | ANALYSIS, Movement Building & Support

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

People often talk about ecological collapse as if it were a distant scenario that might play out in the future, but the reality is that the planet is currently in a state of collapse. This process has been underway for decades.

Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than Nigeria, the most populous nation in Africa and a state still emerging from its legacy as a principal hub of the transcontinental slave trade and decades of British colonial rule.

Although it has long since gained independence, Nigeria has been a virtual oil colony for more than 60 years. Multinational corporations such as Shell and Chevron essentially run the Nigerian government, funding corrupt politicians and military officers to quash all legitimate dissent. Despite the supposed shift to democracy in 1999, Nigeria remains an economic colony run by oligarchs and foreign corporations. Its current president is retired general Muhammadu Buhari, who some locals describe as “Mr. Oil.”[i]

The hardest-hit zone is the oil-rich Niger River Delta, a vast wetland that has been turned into a toxic cesspool by the equivalent of an Exxon-Valdez sized oil spill every single year. Between oil spills, acid rain, and water contamination, the residents of the Niger River Delta are on the front lines of the environmental and capitalist crisis.

In the 1990’s, political opposition to oil extraction in the Niger River Delta became widespread. Much of the resistance was led by women, as Nigeria has a long history of collective women’s action. But the most famous figure of the resistance was Ken Saro-Wiwa, a poet-turned activist who led the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni people (MOSOP).

In 1995, Nigeria’s ruling military dictatorship arrested Saro-Wiwa along with 8 other leaders of MOSOP on trumped-up charges. They were tried and executed by hanging, and their bodies were dumped into a mass grave. This atrocity marked the end of the non-violent campaign in Nigeria and the beginning of a new phase of struggle.

In the mid-2000’s, a militant group emerged in Nigeria known as the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta—MEND. Born out of the failure of non-violence, MEND adopted radical new tactics: kidnapping oil workers for ransom, assassinating executives, and sabotaging oil pipelines, tankers, pump stations, offshore platforms, and other infrastructure.

MEND’s tactics have been innovative, using speed, stealth, and intelligence to target their attacks where they will do the most damage. At the height of their operations, MEND disabled a full half of all oil capacity in Nigeria, the largest oil exporting nation in Africa and a member of OPEC. One analyst writes that MEND’s targets have “been accurately selected to completely shut down production and delay/halt repairs.”[ii]

In 2006, MEND militants released a chilling letter reminding the oil companies of their total commitment.

“It must be clear that the Nigerian government cannot protect your workers or assets. Leave our land while you can or die in it,” the group wrote. “Our aim is to totally destroy the capacity of the Nigerian government to export oil.”[iii]

It is difficult for us to imagine the level of courage it takes for people from the Niger River Delta to rise up in the face of nearly impossible odds against Shell’s elite private mercenary armies and the American-trained special forces units of the Nigerian military.

But we must imagine it, and compare this to our own courage, or lack of courage.

Here in the United States, a grossly inequal and destructive society has been built on land stolen from indigenous people. Slaves built the American capitalism which today is maintained by weapons manufacturers, parasitic drug companies, predatory finance and investment banks, a private prison system that differs little from chattel slavery, and a global oil empire that has been built on the bones of the Ogoni people, on the total poisoning of the Gulf of Mexico, and on the tar sands, the largest and most destructive industrial project on Earth.

The signs of what is happening are so clear ignorance is a willful choice. Just a few days ago, the United Nations warned of imminent “ecosystem collapse.” The IPCC has issued warning after warning of the dire consequences of global warming. Plankton populations, the very foundation of oceanic life and the source of most of the world’s oxygen, are collapsing. Insect populations are collapsing. The last fragments of uncut forests around the world are falling to the chainsaw as fascists and militarists like Bolsonaro, Trump, Putin, Jinping, and Duterte sell off every last fragment of the planet to fund their nationalist, militarist dreams. Coral reefs are dying, wetlands are being drained, and rising seas are expected to make 2 billion people into refugees by century’s end.

As our world teeters on the brink of total ecological and social collapse, we have no more excuses. We have all the information and all the inspiration we need. The times are prompting us to exercise our “revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow” the systems that are murdering the planet and trampling human lives.

If we continue to take no action, we are all cowards. There is no other way to explain our inaction.

Max Wilbert is a third-generation organizer who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement, and works with Deep Green Resistance. He is the author of two books.

[i] Nigeria Oil and Gas: An Introduction and Outlook. By Dele Ogun. Oil and Gas IQ. October 16, 2018. https://www.oilandgasiq.com/market-outlook/news/nigeria-oil-and-gas-an-introduction-and-outlook.

[ii] Nigerian Evoluition. Global Guerillas. January 2006. https://globalguerrillas.typepad.com/globalguerrillas/2006/01/nigerian_evolut.html.

[iii] NIGERIA: Shell may pull out of Niger Delta after 17 die in boat raid. By Daniel Howden. Corpwatch. January 17, 2006. https://corpwatch.org/article/nigeria-shell-may-pull-out-niger-delta-after-17-die-boat-raid.

Photo by Justus Menke on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 21, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

An interview with a comrade from the Deep Green Resistance organization, co-author (with Lierre Keith and Derrick Jensen) of the forthcoming book, Bright Green Lies.

Nicolas Casaux: The latest fad, in the public sphere of mainstream ecology in French speaking Quebec, is this “pact for the transition.” To me it stands for much of mainstream ecology. It is a plea for shorter showers (as Derrick Jensen would call it), based on a naïve belief in the possibility for industrial civilization to become “green”, notably through “sustainable development”, and also a naïve belief in that our leaders, and the State, can and will someday save us all. What do you think?

Max Wilbert: It’s bullshit, like all the mainstream solutions.

In the 1960’s, capitalism was threatened by rising people’s movements and revolution was in the air. One of the main ways that capitalism adapted was by creating the non-profit system to absorb and defuse resistance. Environmental groups like the Sierra Club, 350.org, WWF, and The Nature Conservancy (as well as countless others) all operate with multi-million or billion dollar budgets. That funding comes from foundations; in other words, from the rich via their money laundering schemes. They channel movements towards so-called “solutions” which are really distractions. Sure, in some cases their “solutions” may partially address the issues, but they are being promoted because they are profitable.

This is why we see a massive groundswell movement pushing for “100% renewable energy.” Renewables are extremely profitable. But there is little to no evidence that they actually decrease carbon emissions. Look at overall emissions trends over the past decade. As “renewables” rise, so do overall emissions. That’s because you can’t extricate energy production from growth and the capitalist model. More energy is profitable, and feeds into the growth of the economy (along with population growth, new markets opening up, loans, and other means capitalism uses to grow).

These movements aren’t really grassroots. They’ve been created and funded by massive investments—billions of dollars—worth of grants and foundation funding. That propaganda has convinced millions of people around the world that renewable energy and “green technology” will save the day. And there is absolutely zero evidence that is the case, and plenty of evidence to the contrary. So even when a particular group seems grassroots, their ideology has been created and shaped by these massively funded “Astroturf” organizations.

That’s also why we see such a big focus on personal lifestyle choices. Sure, we should all strive to make moral choices. But “buy or don’t buy” is simply the capitalist model. There is zero threat to the status quo when that is your only weapon. These organizations ask individuals to reduce, but never question empire itself. They never interrogate (let alone threaten) the actual systems of power that are killing the planet. Instead they focus on their silly parochial changes. And I say that as someone who eats as ecologically as possible, drives little, lives in a small cabin in the woods, hunts and forages my own food, etc.

NC: What would you propose to those interested in stopping the current environmental destruction, instead of this pact?

MW: This pact does note that personal changes are insufficient to solve the ecological crisis. That’s good, and it’s a step in the right direction. But they nonetheless put their faith in existing governments and institutions by demanding that they “adopt laws and actions compliant with our climate commitments.” There is no evidence that these institutions will ever live up to the agreements, which are themselves terribly inadequate.

We’re currently on course for more than 4º C of global warming by 2100, and much more after 2100, at the very least. In other words, we’re tracking well beyond the worst case scenarios of the IPCC. Kyoto, Copenhagen, Paris—these have done nothing to slow or reverse these trends. There’s a very real chance this culture could kill more than 90% of all species on this planet, including our own. In fact, we’re well on our way. More than 200 species are driven extinct every day.

Destruction and GHG emissions are built into the structure of modern empire. This society functions by converting the living world into dead commodities. Global warming is merely a symptom of this process. If we want to have a chance in hell of saving the planet, we need to stop focusing on global warming. We need to stop asking governments to save us. We need to stop relying on capitalist, technological solutions. And we need to realize how deadly serious this situation is. We are well along the path towards global fascism, total war, ubiquitous surveillance, normalized patriarchy and racism, a permanent refugee crisis, water and food shortages, and ecological collapse.

We need to build legitimate movements to dismantle global capitalism. All work is useful towards this end. However, I see no way this goal will be achieved without force. The best methods I have come across for achieving this rely on dedicated cadre forming small, highly mobile and trained strike forces. These forces should target key nodes of global industrial infrastructure (shipping, communication, finance, energy, etc.) and destroy them, with the goal of inciting “cascading systems failure.” The interconnected global economy is vulnerable to this type of attack because of how interdependent it is. If the right targets are chosen and effectively attacked, the entire thing could come crashing down.

Obviously this isn’t a magic bullet that will fix every problem. But with ecological collapse now well underway, it is time for desperate measures. This strategy will create the time and space necessary to begin addressing other issues and build sustainable, just societies in the ashes of this corrupt, brutal global empire.

NC: You write that “the agreements” that are presented in this pact “are themselves terribly inadequate”, would you care to elaborate?

Well, this pact is referring specifically to agreements like what came out of Paris. And the deal that came out of Paris was bullshit. It wasn’t actually sufficient to limit warming to 2º C, let alone 1.5º C. All the worst-case scenarios are playing out. We recently passed the “carbon budget” deadline for 1.5º C laid out by the IPCC. And that’s not even to consider the inherent conservatism of science. I’ve written about this in the past, and it’s a critical topic that’s often missed. A meta-review of climate science in 2010 found that “new scientific findings are… twenty times as likely to indicate that global climate disruption is “worse than previously expected,” rather than “not as bad as previously expected.” It’s likely that things are even worse than we think.

After Paris a group of top climate scientists said that Paris would only create “false hope.” And we’ve seen that play out. But the Paris accord isn’t even being followed. There are no nations that are meeting their commitments. We’ve seen this across the board. This isn’t an isolated case. Each international climate treaty has failed in the same two fundamental ways. First, the goals are inadequate to prevent disaster. Second, the goals haven’t been met.

It’s because these conferences aren’t actually meant to solve the problem. They’re largely a political theater meant to built political support for massive subsidies to corporations building wind turbines, solar panels, electric grids, hydroelectric dams, electric cars, etc. These gatherings a massive international events, akin to WTO conventions, at which NGOs, corporations, and politicians can mingle and make deals.

NC: If I was a mainstream environmentalist, I wouldn’t understand why “wind turbines, solar panels, electric grids, hydroelectric dams, electric cars, etc.” are not a good thing, and I would respond that if the goals are inadequate, then we should ask our leaders, our governments, to set adequate goals. Why are “wind turbines, etc.” not a good thing, and what would adequate goals look like?

MW: To understand this, we have to understand how the global economy works. It runs on energy. The more energy is available, the more growth is enabled. For thousands of years, the total amount of energy consumed by global civilization has increased gradually. It jumped massively when coal, oil, and gas were adopted. But even early civilizations burned more and more wood, and harnessed more and more hydropower for mills and so on.

Solar panels, wind turbines, and other forms of “renewable energy” can be accurately seen as a response to peak oil. All the easily exploited oil, coal, and gas has already been burnt. (Unfortunately for all life, there is still a lot left—it’s just very expensive and dangerous to extract). This means that to expand total energy production, new methods are needed. And that’s why we see “unconventional” oil such as tar sands, oil shale, fracking, arctic drilling, and so on.

It’s also why we see this massive boom in solar and wind. Proponents of these technologies like to trumpet headlines about costs for solar electricity, for example, falling lower than coal in some areas. And because of this, corporations are going all-in. We now see “renewable” energy powering Apple’s data centers, Intel’s factories, Ford production lines, and Wal-Mart stores. Hell, even the US Military is investing heavily in “green energy” for bases and outposts.

People like Bill McKibben and Mark Z. Jacobson look at this as a major success. But the fact is, the boom in solar and wind hasn’t caused emissions to decline. If you look at a few localized areas, you are seeing emissions declines. But most of this comes down to fraudulent accounting, and the key fact that it’s somewhat useless to look at local or even regional emissions in a globalized, interconnected economy. What they hell does it matter if emissions decline in Germany, when they import all their solar panels from China (the #1 polluter now, globally, due to their status as a production center for the rich nations and a rising superpower in their own right) and export millions of brand new cars around the world?

Global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. That’s the key element. We can look at these localized claims of emissions declines as mostly being a form of “carbon laundering,” whereby mostly rich nations are able to claim they’re saving the world while continuing to profit off the backs of the economic colonies. Just like they imported slaves in the past, now they export carbon emissions. It’s all part of the theater and power politics of global empire.

This has been quantified by a sociologist named Richard York, who has shown that bringing online new “green” energy doesn’t actually displace the burning of fossil fuels. In other words, when you add a new wind energy installation, you don’t turn off a coal plant of equivalent size. In practice, the new energy is simply added on top. And that’s where it all comes back to growth. This is a massive growth opportunity for the capitalists. Businesses are practically drooling over the prospect of massive public subsidies for these “sorely needed” renewable energy projects, not to mention electric cars and so on.

So the bottom line is that green energy doesn’t work. Period. Green technology doesn’t work. People can talk about future scenarios all they like, but it’s not working right now.

But people continue to believe in these lies, and that’s because of the propaganda. Look at any mainstream ecology or even liberal news source. They all promote green technology like a religious savior. It’s because they can’t imagine questioning empire itself. The idea of ending this way of life is obscene to them. More accurately, it’s literally unthinkable.

But to look for rationality in all this is silly. My friend Derrick Jensen often says that the dominant culture has “death urge, an urge to destroy all life.” The author Richard Powell explained it in a different way, writing that “the motive behind all of this “deregulation” is not primarily economic. Any reasonable accounting reveals that the sum of these measures carries external costs far greater than the hoped-for benefits. (Did you know that the number-one killer in the world is pollution? And that doesn’t even include premature deaths from climate change.) The push to remove all environmental safety strikes me as mostly psychological. It’s driven by a will to total dominance, underwritten by the hierarchy of values that George Lakoff calls “stern paternalism,” putting men above women, whites above minorities, Americans above all other countries, and humans above all other living things.”

But I would add, just because it’s psychological doesn’t mean it’s not real. The world today is being run by people who believe in money as a god. They’re insane, but they have vast power, and they’re using that power in the real world. That’s the physical manifestation of their violent, corrupt ideology.

NC: So when you write “the idea of ending this way of life is obscene to them”, you mean that they don’t want to give up the modern industrialized way of life? Because in the end that’s the only way out, right? Giving up the modern, industrialized, high-tech way of life, and going back to —or inventing new forms of— small scale and low-tech living? Because, I don’t know about the US, but in France, and in Europe in general, we have this ecosocialist movement, who thinks it’s possible to have both degrowth AND a kind of green industrialism, to develop renewables AND to remove or give up on fossil fuels, to abolish or drastically diminish the use of the individual car and promote public transportation, to choose electrical rail transport instead of trucks, and so on, in short to rationalize the industrial mess, democratically, and to make it green/sustainable. What do you think about that?

MW: I sympathize with the degrowth socialists. I agree with many of them, especially the revolutionary ecosocialists, on a lot of issues. And I enjoy engaging in dialogue with them. I do think that it is physically possible to implement a degrowth model in which the vast majority of consumption is ended. Of course, there is zero political will for that, which is why degrowth must be a revolutionary struggle. Reform and electoral politics will never lead to deliberate degrowth.

But it’s a mistake to think that further development of “renewables” is possible with a degrowth model. Renewables are, without exception, fully dependent on fossil fuels. Take wind turbines, for example. The blades are made of plastics from oil. The steel in wind turbines is made with massive quantities of coke, which is a form of coal. Steel is one of the most toxic industries on the planet, and it’s essential for wind and many of the other “green” technologies. Wind turbines are lubricated with oil. Each turbine requires hundreds of gallons. In fact, Exxon Mobil has a whole wind turbine lubricant division. Turbines are transported into place on fossil fuels-powered trucks, lifted upright by cranes running on diesel, and bolted into foundations made of concrete (a highly energy intensive material) dug by diesel-powered machinery. We could go on and on.

It’s the same with solar. Where does the silicon mining happen? It happens with massive dump trucks which guzzle gallons of diesel per minute. And most solar panels are made in China, so they’re shipped across the ocean on massive vessels. The 100 largest ocean ships pollute more than all the cars in the world.

That’s not even to go into the water issues, pollution, labor exploitation, economic issues. A solar panel production factory is a $100 million facility. In other words, there is no way to make this technology community-scale. You need a globalized economy and massive capital investment to create these “renewables.” And this all runs on oil.

Degrowth socialists should take a more realistic perspective on these issues. The reality is, the planet has limits. The history of industrialism shows those limits. Steel production is not sustainable. Neither is the production of any of the other raw materials that are essential for green technologies. These aren’t simply claims I’m making. This is the physical reality.

A high-tech, ecological, post-capitalist society is a fantasy. We need to recognize what is sustainable, and what isn’t. Factories are not sustainable, whether they are producing hummers or electric buses. Electricity production is not sustainable. I organized an event years ago with Chief Caleen Sisk of the Winnemum Wintu. She grew up with no electricity on Indian land, and she reminded us that “electricity is a convenience. We can live without electricity, but we can’t live without clean water.” I’ve studied the issue and see no way to produce electricity, in the long haul, that doesn’t poison water and destroy the land.

Scientists and techno-priests can talk all they want about green energy and a renewable future, but whenever you analyze the full life-cycle of the technologies, they look like the same old planet-destroying bullshit. So I don’t see technology providing a way out. The best-case scenario I see is that people dismantle capitalism forcefully, via revolution. At the same time, we need to engage in relentless education to teach people the reality of ecological limits and our tasks for the future.

Mass society has some inherent characteristics that make it challenging, if not impossible, to be sustainable or egalitarian. It’s too easy to outsource destruction. Out of sight, out of mind. Look at sweatshop labor, mining, and so on. And it’s too easy for elites to take over the political process. That’s been the history of the last 8,000 years right there. It’s the history of empire.

If we want an egalitarian society, it needs to be in the form of local, autonomous communities. I think the democratic confederalism experiment in northern Syria is an interesting project in this regard. Confederations allow communities to collaborate, trade, work to protect one another from predatory and expansionist groups, and so on. But they preserve the local autonomy and decision-making power that’s essential for sustainability.

We need to replace global society and nation-states with thousands of hyper-localized communities, living with the boundaries of the natural world. These post-capitalist societies aren’t likely to shun electricity and other modern conveniences entirely. We don’t have to throw away every advancement of science and technology from the last 10,000 years. But it’s more likely these societies would jury-rig small-scale electric generation from the scraps of empire than that they’ll have full-fledged solar panel production factories. Long-term, industrial technology is going to disappear.

NC: We have, in France, a growing current, which called itself collapsologie (collapsology). It’s essentially composed of people who have understood that the collapse of industrial civilization is guaranteed, but are mainly concerned by building more resilience (emotional and material), for them and their communities, or elaborating national politics for going through the collapse of industrial civilization, but not fighting against empire, but not fighting for the living. What do you make of that?

MW: It’s a morally bankrupt position. The only way to justify not fighting empire is if you identify with the system. I’ve long been told that we need to decolonize ourselves, and a big part of that is breaking our psychological affiliation with empire and all its components: modern conveniences, culture, food systems, etc. Once we step outside of fear that these systems support our lives, it’s incredibly easy to see that these systems are destroying the planet.

Then, we need to go a step further—and this is the step that most people forget. We need to make our allegiance to the living planet. We need to identify with the greater-than-human world. This can be done at multiple levels. At the basic level, of course, is the physical understanding that we’re dependent on clean water, clean air, clear soil, etc. These are created and maintained by the biotic community, the community of life.

But having only a physical understanding is dangerous, because it can lead to a utilitarianism. We see this reflected in the environmental sciences in ideas like “ecosystem services,” where you try to quantify and put a dollar value on clean water. But the thing is, as soon as you attach a dollar value, that can be used against you, because if the economic value of the industry is greater than the value you’ve found for the water, your argument is moot. By using that capitalist, utilitarian language and argumentation, you’re granting one of their fundamental premises: that the economic factor is the most important.

We need to go to a deeper, spiritual level. Animism is the belief in spirits of the land, a belief that the land itself—mountains, rivers, clouds, storms, and so on—is alive. Some form of this belief system is shared amongst the vast majority of indigenous peoples worldwide. And it’s not a mystery why. I would argue that this is an adaptive trait. To survive in the long term, to live on the land without destroying it, human beings need a narrative that teaches us respect.

I think you can get to a similar mindset in many different ways. For me, it doesn’t really matter if we look at the world as collections of atoms self-organizing into beings, communities, landscapes, with billions of complex chemical reactions supporting the whole, or if we look at it as a world animated by spirits. The sense of awe is immense either way.

We are living in a world of astounding beauty and wonder. I love the world. I love my friends and my human community. I love the oak trees outside my window. I love the meadow beyond them. I love the deer, the wild turkeys, the voles, the spring flowers. I love the seasonal creek that flows nearby. I love the great evergreen forests in the mountains. I love the coastline, and the beings who live there. These aren’t abstract feelings. These are real communities who I have a relationship with.

And they’re being murdered. Within my region you have logging, mining, spraying of pesticides, road building, housing “development,” and worse. This is the economic system of empire, laying waste to this area slowly but surely, just as it does elsewhere. And this is in the US, the heart of empire. It’s much worse elsewhere, on the frontiers and in the economic colonies. And then there are the existential threats of global warming, nuclear annihilation, toxification, and so on.

It’s not that death itself is a problem. I am a hunter, I harvest plants, I take life, but I do so with respect and ensure the community as a whole is healthy. This isn’t comparable to what empire does. Again, civilization is a culture with a death urge, an urge to destroy life. When we see this, and we love the world, not fighting back is unthinkable.

When I hear people who recognize collapse, but who don’t want to fight empire, I feel pity and anger. They must have no love for the living world. But they’re not necessarily a lost cause. Some people can learn to change their beliefs, change their minds, and most importantly to change their actions. But once they are indoctrinated into a certain worldview, most people don’t change.

I agree with these people that we need to build individual and collective resilience. But not simply for the sake of survival, which is ultimately selfish. We need to do it to have a strong foundation for our resistance. We need revolutionary change, not lifeboat survivalism.

Photo: solar panels at the Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, U.S.A. Public domain.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 15, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis