Editor’s note: As the climate catastrophe worsens, chaos and contradiction reigns. Grassroots people’s resistance to the fossil fuel industry is growing, but so is government repression, and investment in coal, oil, and gas continues to grow (last year, more than 83% of global energy was supplied by fossil fuels). Meanwhile, governments are censoring the true depths of the crisis and a rush of big-businesses are seeking to capitalize on global warming, seeing a massive “shock doctrine” opportunity for profiting off the crisis.

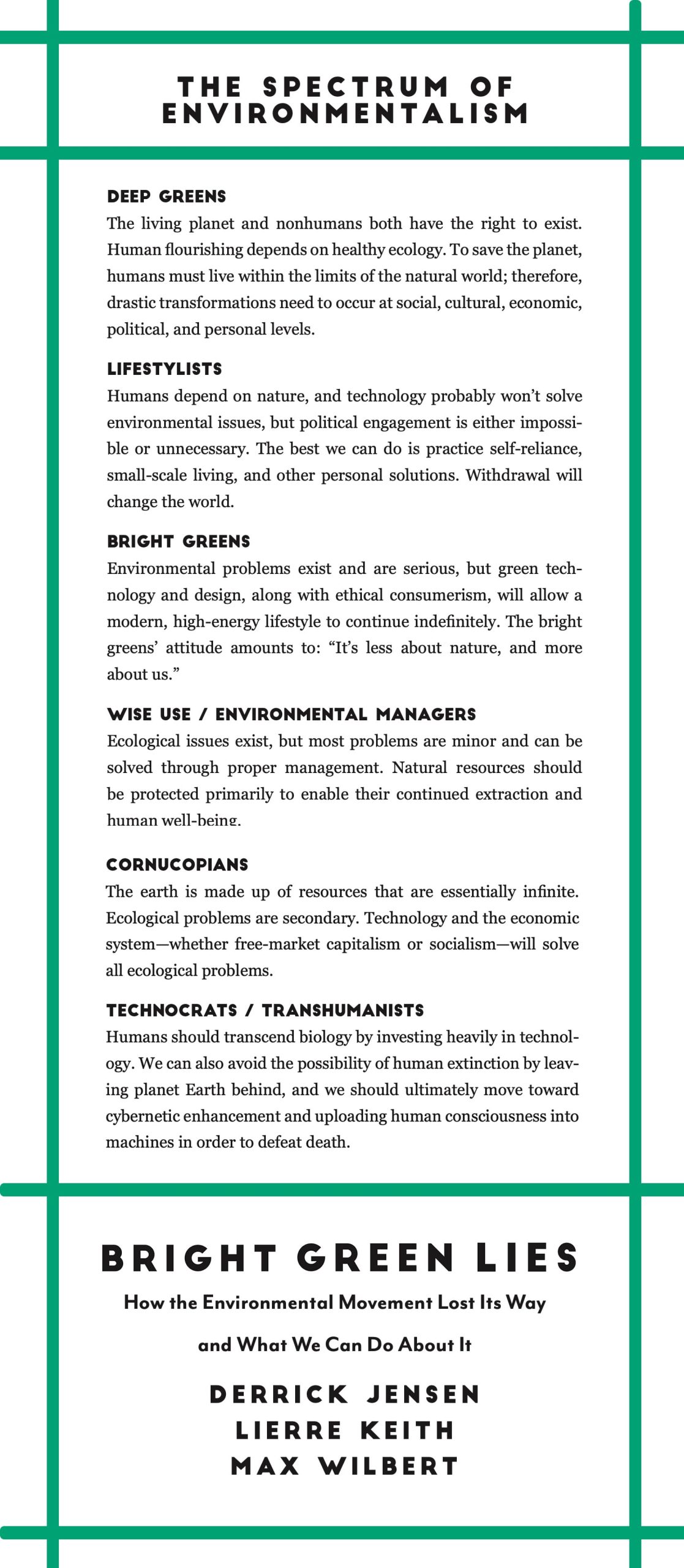

Today we bring you an excerpt from the book Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Max Wilbert, a book which Chris Hedges says “asks the questions most refuse to ask, and in that questioning, that seeking, uncovers profound truths we ignore at our peril.”

This excerpt uses Naomi Klein’s concept of the “Shock Doctrine” to analyze how big business has co-opted the environmental movement into a de-facto lobbying arm for the so-called “green” technology industry, and in the process has turned away from the fundamental values of the environmentalism.

It shouldn’t surprise us that the values of the environmental movement have degraded so much in the last 30 years.

It shouldn’t surprise us that the values of the environmental movement have degraded so much in the last 30 years.

Now more than ever, people are immersed in technology instead of the real world. As one report states, “The average young American now spends practically every minute—except for time in school—using a smart- phone, computer, television or electronic device.” A recent poll in Britain found that the average 18-to-25-year-old rated an internet connection as more important than daylight.

We’ve come a long way from the naturalists we were born to be; from inhabiting a living world flush with kin to serving a society in thrall to machines.

It’s no wonder, then, that so many people believe in nonsensical technological solutions. Technology does it for them and the real world doesn’t.

And so, the absurd becomes normal. We hear that green technology will stop global warming. We hear that cutting down forests and burning them is good for the planet. We hear that damming rivers is good for the planet. We hear that destroying the desert to put in solar panels is good for the planet. We hear that industrial recycling will save the world. We hear that commodifying nature is somehow significantly different than business as usual. We hear that we can invest our way to sustainable capitalism. We hear that capitalism can be sustainable.

A global growth rate of 3 percent, which is considered the mini- mum for capitalism to function, means the world economy doubles every 24 years. This is, of course, madness. If we can’t even name capitalism as a problem, how are we to have any chance of saving the planet?

There’s no doubt that global warming is apocalyptic. I (Max) have stood on thawing permafrost above the Arctic Circle and seen entire forests collapsing as soils lose integrity under their roots. This culture is changing the composition of the planet’s climate. But this is not the only crisis the world is facing, and to pretend otherwise ignores the true roots of the problem.

The Sierra Club has a campaign called “Ready for 100.” The campaign’s goal is to “convince 50 college campuses, a dozen key cities and half a dozen key states to go 100 percent renewable.’” The executive director of the Sierra Club, Michael Brune, explains,

“There are a few reasons why Ready for 100 is working—why it’s such a powerful idea. People have agency, for one. People who are outraged, alarmed, depressed, filled with despair about climate change—they want to make a difference in ways they can see, so they’re turning to their backyards. Turning to their city, their state, their university. And, it’s exciting—it’s a way to address this not just through dread, but with something that sparks your imagination.”

There are a lot of problems with that statement. First, is Ready for 100 really “working,” like Brune says? That depends on the unspoken part of that statement: working to achieve what? He may mean that the campaign is working to mobilize a larger main- stream climate movement. He may mean that Ready for 100 is working in the sense that more “renewable” infrastructure is being built, in great measure because more subsidies are being given to the industry.

If he means Ready for 100 is working to reduce the burning of coal, oil, and gas—which is, in fact, what he means—he’s dead wrong, as “fossil fuels continue to absolutely dominate global energy consumption.”

There’s more about Brune’s quote that’s bothersome. He’s explicitly turning people’s “outrage, alarm, depression, and despair” into means that serve the ends of capital; through causing people to use these very real feelings to lobby for specific sectors of the industrial economy.

If a plan won’t work, it doesn’t matter if people have “agency.” The ongoing destruction of the planet, and the continued dominance of coal, oil, and gas, seems to be less important than diverting people’s rage—which, if left unchecked, might actually explode into something that would stop capitalism and industrialism from murdering the planet—into corporate-friendly ends.

Led by 350.org, the Fossil Free campaign aims to remove financial support for the coal, oil, and gas industries by pressuring institutions such as churches, cities, and universities to divest. It’s modeled on the three-pronged boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) resistance to South African apartheid (a model used today against Israel). The Fossil Free campaign has thus far pressured 800 institutions and 58,000 individuals to divest $6 trillion. Some of these are partial divestments, such as withdrawing from tar sands but continuing to fund fracking.

Still, sounds great, right? Anyone fighting to stop coal, oil, and gas is doing a very good thing.

But given how little time we have, and how badly we’re losing the fight for the planet, we have to ask if divestment is an effective strategy.

The answer, unfortunately, is not really. Jay Taber of Intercontinental Cry points out that “All this divestment does is make once publicly held shares available on Wall Street, which allows trading houses like Goldman Sachs to further consolidate their control of the industry. BDS, when applied against apartheid states by other states and international institutions, includes cut- ting off access to finance, as well as penalties for crimes against humanity.” He states quite bluntly that divestment acts to “redirect activism away from effective work.”

Bill Gates—not usually someone we’d listen to—seems to agree. “If you think divestment alone is a solution,” Gates writes, “I worry you’re taking whatever desire people have to solve this problem and kind of using up their idealism and energy on something that won’t emit less carbon—because only a few people in society are the owners of the equity of coal or oil companies.”

If it occurs on a wide enough scale, divestment makes previously held stocks, bonds, and other investment products available for purchase. This glut drops prices, making it easier for less ethical investors to buy. This not only consolidates the industry, but it also makes fossil fuel stocks more profitable for those who snatch them up. As journalist Christian Parenti writes, “So how will dumping Exxon stock hurt its income, that is, its bottom line? It might, in fact, improve the company’s price to earnings ratio thus making the stock more attractive to immoral buyers. Or it could allow the firm to more easily buy back stock (which it has been doing at a massive scale for the last five years) and thus retain more of its earnings for use to develop more oil fields.”

It’s unlikely any divestment campaigner believes divestment alone will stop global warming. The Fossil Free website recognizes this, writing: “The campaign began in an effort to stigmatize the Fossil Fuel industry—the financial impact was secondary to the socio-political impact.” But as the amount of money being divested continues to grow, reinvestment is becoming a more central part of the fossil fuel divestment campaign. The website continues: “We have a responsibility and an opportunity to ask ourselves how moving the money itself … can help us usher forth our vision.”

Great! So, they’re suggesting these organizations take their money out of oil industry stocks, and use that money to set aside land as wilderness, for wild nature, right?

Well, no. They want the money to be used to fund “renewable energy.” And they’ve slipped a premise past us: the idea that divestment and reinvestment can work to create a better world. It’s an extraordinary claim, and not supported by evidence. As Anne Petermann of the Global Justice Ecology Project writes, “Can the very markets that have led us to the brink of the abyss now provide our parachute? … Under this system, those with the money have all the power. Then why are we trying to reform this system? Why are we not transforming it?”

Activist Keith Brunner writes, “Yes, the fossil fuel corporations are the big bad wolf, but just as problematic is the system of investment and returns which necessitates a growth economy (it’s called capitalism).” His conclusion: “We aren’t going to invest our way to a livable planet.”

Is it better to fight for “achievable, realistic” goals through reform, or address the fundamental issues at their root? Usually, we’re in favor of both. If we wait for the great and glorious revolution and don’t do any reform work (which we could also call defensive work), by the time the revolution comes, the world will have been consumed by this culture. And if we only do defensive work and don’t address the causes of the problems, this culture will consume the world until there’s nothing left.

But it’s pretty clear that the real goal of the bright greens isn’t defending the planet: Everyone from Lester Brown to Kumi Naidoo has been explicit about this. The real goal is to get money into so-called green technology. A recent article notes, “Climate solutions need cold, hard cash … about a trillion a year.”

One of Naomi Klein’s biggest contributions to discourse is her articulation of the “shock doctrine,” which she defines as “how America’s ‘free market’ policies have come to dominate the world—through the exploitation of disaster-shocked people and countries.” In her book The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, Klein explains—brilliantly—how the same principles used to disorient and extract concessions from victims of torture can be leveraged to extract political concessions from entire nations in the wake of major disasters. She gives many examples, including the wave of austerity and privatization in Chile following the Pinochet coup in 1973, the massive expansion of industrialism and silencing of dissidents following the Tienanmen Square massacre in China in 1989, and the dismantling of low-income housing and replacement of public education with for-profit schools in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

The shock doctrine also perfectly describes the entire bright green movement: Because of a terrible and very real disaster (in this case, climate change), you need to hand over huge subsidies to a sector of the industrial economy, and you need to let us destroy far more of the natural world, from Baotou to the Mojave Desert to the bottom of the ocean. If you don’t give us lots of money and let us destroy far more of the natural world, you will lose the luxuries that are evidently more important to you than life on the planet.

Once you start looking for this trend, it’s really clear. There’s a 2016 article in Renewable Energy World magazine about the Desert Renewable Energy and Conservation Plan. The plan allows major solar energy harvesting facilities to be built in some areas of the California desert, but not other areas. Shannon Eddy, head of the Large-Scale Solar Association, considers protecting parts of the desert “a blow.” She says, “The world is on fire—CO2 levels just breached the 400-ppm threshold. We need to do everything we can right now to reduce emissions by getting renewable projects online.”

Everything including destroying the desert. This is reminiscent of a phrase from the Vietnam War era, which originated in 1968 with AP correspondent Peter Arnett: “‘It became necessary to destroy the town to save it,’ a United States major said today.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can order the book Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What We Can Do About It to your local bookstore or anywhere you find books. It’s also available in audiobook format on Audible and other platforms.

We also invite readers to get involved in people’s movements against greenwashing and for degrowth, resistance to industrial civilization, humane population reduction, and for the land. You can learn more about an active struggle over these issues at Protect Thacker Pass.

This was an excellent book. If you want the details instead of just generalizations like the film Planet of the Humans, read this book.

Thanks, Jeff!

So many books on what’s wrong but nothing on how to get things right. It starts with the way we communicate with each other. I wrote a critique of Derrick Jensen’s Declaration and thought Derrick might be interested but he was only interested if I had had any books published. It’s so “superior”. And that’s how we are with each other. When what we need to be is egalitarian. I write what I feel is worthy and not interested in having a publisher compromise my work. Plenty of books have been written and where has it gotten us? However I write to change the world by changing the mechanics of thought. Here is the critique and Derrick was must ungracious which put me off him and consider DGR to be just more pissing in the wind. We need hard-core strategies if we are to turn this baby around. (sorry but it cannot be done in a soundbite) https://deniseward.medium.com/a-review-of-derrick-jensens-declaration-12f6fe6817be

Just a thought, are there individuals who want to end fossil fuels living without the benefits of these materials? I’ve worked in heavy industry for 44 years and the amount of resources necessary just to provide essentials is staggering, no amount of wind, solar, wave or whatever is going to replace coal, gas and oil… I have also lived a primitive lifestyle for short periods of time and it’s not all it’s cracked up to be.

The excerpt concentrated on what has “gone wrong” with environmentalism and not on what people concerned about the environment should do, although this is on the title.

So how should we be effective? I get that the ‘deep greens’ think that humanity should live within the natural limits of the world – but how do we persuade humanity to do this?

I think people in rich countries will just ignore us if we try to persuade them that they have to live their lives without electricity or transport or heating. So trying to make these things less harmful is a worthy project.

Prove me wrong. Tell me what the plan is DGR.

Guy – check out the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet for a full explanation of our movement’s strategy.

The only “renewable energy” is sunshine as it falls to Earth, enabling plants to grow and feed animals, etc.

“Solar farms” and “wind farms” are made from non-renewables, such as plastic solar panels and plastic wind turbine blades (plastic being a byproduct of fossil fuels), and lithium ion batteries (made from non-renewables, such as lithium, copper, cobalt, and rare earth minerals, extracted by diesel-powered equipment). These items are largely non-recyclable and non-biodegradable, and are installed by diesel-powered tractors and trucks.

Such “greenwashing” only postpones civilization’s crash, and makes it infinitely more lethal and destructive when it comes.

I agree and disagree with every comment here and I don’t have the solution or answers because no one does or ever will. However, even if we are doomed what’s the point of fighting amongst ourselves over perfect solutions? Of course, this is exactly what the ‘powers that be” literally bank on – people who could be encouraging inclusivity and working with each other instead circling the wagons and firing inward – divide and conquer by the very forces that we oppose. But on the other hand, I also realize that so long as the majority of people are brainwashed by capitalism and corporate propaganda then we have a duty to challenge the assumptions and naivette of people trying to solve environmental crises which of course usually makes them defensive but too bad if we hurt their feelings because the world is on fire. Perhaps one could have a non-dualistic approach to all of this and one can openly embrace both of these approaches. Or perhaps I’m just being too open-minded and contrarian….or maybe I’m not? No matter what, I strive to live a life of joyful defiance even if I’m going to hell in a bucket at least I’ll enjoy the ride, to paraphrase Jerry G

Thank you, Jeff. Well said.