by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 4, 2017 | Lobbying

by Real World Radio via Intercontinental Cry

After eight years of struggle, communities in Santa Cruz Barillas, Guatemala, are celebrating a decision by Spanish company Ecoener-Hidralia to leave Guatemala and start the “process of extinction of Hidro Santa Cruz S.A.”

The Dec. 29 announcement signals the end to a tragic legacy of political persecution and imprisonment, criminalization of resistance, threats and the murder of social leaders.

The aggressiveness of the hydro dam’s proponents reached its highest point with the murder of community leader Andrés Pedro Miguel, attributed to security officers hired by the multinational company. Legal authorities, even in light of undisputed evidence, decided to keep this crime unpunished.

The outrage of communities was used as an excuse by the Guatemalan government, led by Otto Pérez Molina, to declare a state of emergency in the area and imprison several people.

“As the people of Barillas we see this as a great victory. This is an important achievement towards the defense of the territory and the natural resources of the people, and it is a message for other companies in the country and the world,” said Basilio Tzoy, member of the Departmental Assembly of Huehuetenango and CEIBA – Friends of the Earth Guatemala, in an interview with Real World Radio.

Tzoy believes that the “key factor” for this victory was the struggle of “the people through community consultations since 2007, and then with the support of different organizations and individuals who opposed the state of emergency in 2012 and advocated for the freedom of the political prisoners.”

Tzoy also highlighted the importance of the solidarity shown by regional and international organizations that acted to stop the advance of the project, for instance through the International Mission on Human Rights carried out in 2013 in the framework of the 5th Latin American Meeting of the “Network of People Affected by Dams and in Defense of Rivers, Communities and Water” (REDLAR).

Another important action, according to him, was the delivery of over 23 thousand signatures gathered by Friends of the Earth Spain and the Alianza por la Solidaridad to the Guatemalan Ambassador in Spain, demanding the definitive withdrawal of the multinational company from the country.

The struggle continues

In addition to celebrating this victory, the communities have identified as next steps to strengthen the solidarity with the q’anjob’al and chuj peoples of San Mateo Ixtatán municipality, who are facing the advance of hydroelectric projects owned by company Promoción y Desarrollo Hídricos (PDHSA). According to Tzoy, the leaders of these communities, who live in a heavily militarized territory, have “over 17 arrest warrants against them and over 50 legal complaints,” for defending their territories.

With reference to the territories occupied by Hidro Santa Cruz, the activist said that starting next year, the local organizations will meet to define how they will be recovered.

In the framework of the 20th anniversary of the peace agreements today, December 29th, Tzoy said that Guatemalan social movements have been meeting for over two months now, carrying out actions to demand the State the right of Indigenous Peoples to their territories and to denounce the attacks and criminalization of the struggles of the communities.

As a conclusion, Basilio Tzoy addressed “the people of Latin America and the world resisting neoliberalism: the struggles take long and are hard, but the fruits can be reaped as long as they persevere,” said the Guatemalan leader.

This article was originally posted at RadioMundoReal.fm and edited and re-published at Intercontinental Cry under a Creative Commons License. Featured image by www.papelrevolucion.com.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 10, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

Mayanga family slaughtered by illegal colonizers while planting food on traditional land

Warning: this article includes graphic images that some readers may find disturbing.

by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

In a shocking escalation of the ongoing violent conflict devastating the Indigenous binational autonomous nation of Moskitia, a Mayanga family of three was killed in a brutal attack by ‘Colonos’ at the Llano Sucio site of the Alamikamba community in the Awala Prinsu territory on November 27, 2016. The attack sent shockwaves through the already war torn territories of Moskitia.

The family’s names and ages were documented by community members; and, the Miskito community continues to seek international solidarity amidst this tragedy and related ongoing devastation. The Mayanga individuals who lost their lives in this most recent and exceptionally brutal attack, have been identified as:

Bernicia Dixon Peralta, age 30 (family and community members claim she was between 3 and 5 months pregnant);

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Feliciano Benlis Flores, age 37;

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

And, their 11 year old son, Feliciano Benlis Dixon.

Photo: Cejudhcan Derechos Humanos

Reports from the community indicate the family was on the receiving end of threats from invading Colonos – heavily armed Mestizo settlers encroaching on Miskito territory, acting as agents of a large scale land grab. They also say these threats were fully realized last weekend while the family was attempting to plant seeds on their traditional land.

Eklan James Molina, mayor of Alamikamba, which is located in the municipality of Prinzapolka, has demanded a thorough investigation of the massacre. In a statement to one of the few independent news outlets in Nicaragua, La Prensa, he charged: “As mayor, I ask the police and the army to follow up on the case. You have to get to the bottom of why it [occurred].”

In the article published by La Prensa, unverified claims surfaced suggesting the deceased family’s land had been illegally sold to the violent, encroaching settlers by a mysterious third party. Nancy Elizabeth Henriquez, deputy of the YATAMA Indigenous political party – the only real political opposition to the Sandinista state in the region at this time – has dismissed such claims as already having been settled in a court of law; and, explicitly categorized this recent massacre as a revenge killing. In her statement to La Prensa, she relayed, “The owner sued and won the right [to the land] that is theirs; and the Colonos killed the entire family for revenge.” She cited ongoing ethnic clashes as one potential reason the Nicaraguan National Police continue to allow such atrocities to take place with impunity.

Moskitia, a lesser known conflict zone where the violent and heavily armed Meztizo settlers from the Pacific coast and interior of Nicaragua continue to invade traditional and legal Miskito land, has been experiencing escalations in terrorism and violence since June of 2015, according to an official statement issued by the Miskito Council of Elders in August of this year. In a statement published by The Ecologist in October, the elders explained:

“Since ancient times we’ve [cared for] our forests, because apart from being our only means of sustenance, we understand that any alteration to [them] attracts risks; alters our form of life; puts existence itself at risk; causes drastic changes [to] the climate; alters the ecosystem; and breaks our link with our ancestors.

[For] little more than five years, [we] have experienced the largest internal colonization [of] our history. The presence of ‘Colonos’ has drastically altered our form of life. In such a short time [the invasion] has destroyed tens of thousands of hectares of our forests, which has led to [the drying of] our rivers, [causing] the animals [to] migrate and the climate to alter, and us to emigrate. Our large forests are now deserts, occupied for the livestock, and [we] can do nothing to curb the advance of the settlers as they have the support of the Government of Nicaragua and [we] are alone.”

***

At this point, the much hyped November presidential election in Nicaragua has come and gone. President Daniel Ortega managed to further consolidate power and formally establish the foundations for a family dynasty and authoritarian dictatorship. All fanfare aside, Fidel Castro’s recent death means little in a pragmatic sense to the quasi-socialist, former Sandinista revolutionary, Ortega; his contradictory embrace of neoliberalism has carved out even more geopolitical space for a disturbing emerging brand of neoliberal authoritarianism – more in line with Putin’s newly conservative Russia, the theocratic regime of Iran, and the authoritarian capitalism embraced by China, than Fidel’s revolutionary ideals in Cuba. It is thus likely no coincidence that all three of the aforementioned nations have sought a stake in the notorious Nicaragua trans-oceanic canal. After mounting skepticism regarding whether the environmentally catastrophic, human rights disaster would actually come to fruition, recent reports have cited the monstrous development project may be poised to move forward after all. At least 11 non-violent protestors were recently injured amid the growing anti-canal movement.

Another recent report from La Prensa indicates the continued violent expansion of the agricultural frontier into the Indigenous nation of Moskitia – which includes the second largest tropical rainforest in the Western Hemisphere after the Amazon, referred to as the ‘lungs of Mesoamerica’ – may also be tied to Russia’s increasing imperialist presence in the region. A key player in the re-militarization of Nicaragua, Russia recently sold the impoverished nation an estimated 80 million dollars’ worth of military war tanks (some suggesting to suppress ongoing internal dissent) and is launching a strange new imperial drug war in the region. It is unclear what stake Russia has in fighting a drug war in Central America, but the La Presna report suggests that they may be hoping for a payoff in agricultural land appropriated through recent land grabs and ongoing deforestation.

Featured image: A young Miskitu girl stands before an armed indigenous resistance force in Muskitia, Nicaragua. From Ecologist Special Report: The Pillaging of Nicaragua’s Bosawás Biosphere Reserve, by Courtney Parker

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

by Jen Moore / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Stories of bloody, degrading violence associated with Canadian mining operations abroad sporadically land on Canadian news pages. HudBay Minerals, Goldcorp, Barrick Gold, Nevsun and Tahoe Resources are some of the bigger corporate names associated with this activity. Sometimes our attention is held for a moment, sometimes at a stretch. It usually depends on what solidarity networks and under-resourced support groups can sustain in their attempts to raise the issues and amplify the voices of those affected by one of Canada’s most globalized industries. But even they only tell us part of the story, as Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber make painfully clear in their new book, The Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America (Fernwood Publishing, November 2016).

“Rather than a series of isolated incidents carried out by a few bad apples,” they write, “the extraordinary violence and social injustice accompanying the activities of Canadian capital in Latin America are systemic features of Canadian imperialism in the twenty-first century.” While not completely focused on mining, The Blood of Extraction examines a considerable range of mining conflicts in Central America and the northern Andes. Together with a careful review of government documents obtained under access to information requests, Gorden and Webber manage to provide a clear account of Canadian foreign policy at work to “ensure the expansion and protection of Canadian capital at the expense of local populations.”

Fortunately, the book is careful, as it must be in a region rich with creative community resistance and social movement organizing, not to present people as mere victims. Rather, by providing important context to the political economy in each country studied, and illustrating the truly vigorous social organization that this destructive development model has awoken, the authors are able to demonstrate the “dialectic of expansion and resistance.” With care, they also show how Canadian tactics become differentiated to capitalize on relations with governing regimes considered friendly to Canadian interests or to try to contain changes taking place in countries where the model of “militarized neoliberalism” is in dispute.

The spectacular expansion of “Canadian interests” in Latin America

We are frequently told Canadian mining investment is necessary to improve living standards in other countries. Gordon and Webber take a moment to spell out which “Canadian interests” are really at stake in Latin America—the principal region for Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) in the mining sector—and what it has looked like for at least two decades: “liberalization of capital flows, the rewriting of natural resource and financial sector rules, the privatization of public assets, and so on.”

Cumulative CDIA in the region jumped from $2.58 billion in stock in 1990 to $59.4 billion in 2013. These numbers are considerably underestimated, the authors note, since they do not include Canadian capital routed through tax havens. In comparison, U.S. direct investment in the region increased proportionately about a quarter as much over the same period. Despite having an economy one-tenth the size of the U.S., Canadian investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is about a quarter the value of U.S. investment, and most of it is in mining and banking.

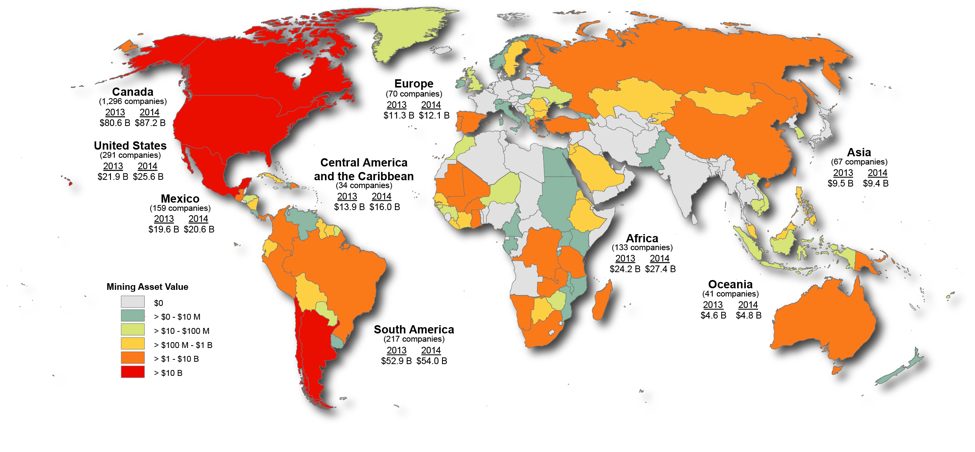

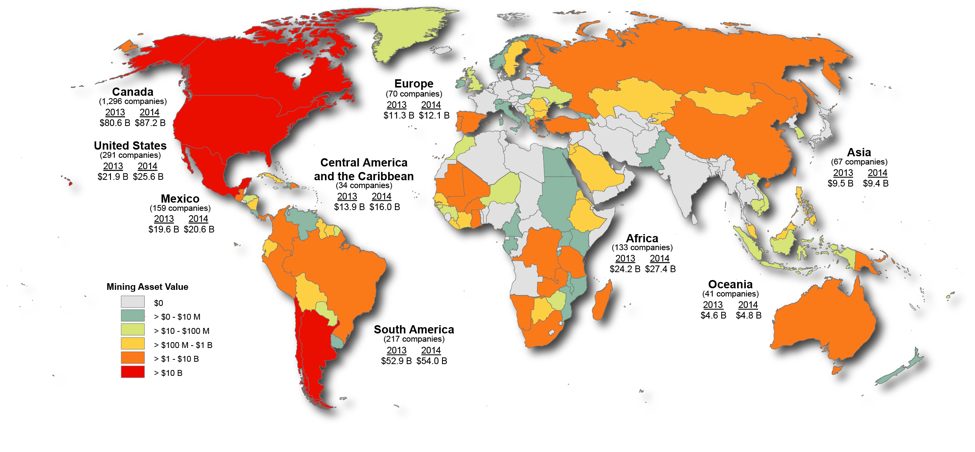

Canadian mining investment abroad

To cite a few of the statistics from Gordon and Webber’s book, Latin America and the Caribbean now account for over half of Canadian mining assets abroad (worth $72.4 billion in 2014). Whereas Canadian companies operated two mines in the region in 1990, as of 2012 there were 80, with 48 more in stages of advanced development. In 2014, Northern Miner claimed that 62% of all producing mines in the region were owned by a company headquartered in Canada. This does not take into consideration that 90% of the mining companies listed on Canadian stock exchanges do not actually operate any mine, but rather focus their efforts on speculating on possible mineral finds. This means that, even if a mine is eventually controlled by another source of private capital, Canadian companies are very frequently the first face a community will see in the early stages of a mining project.

The results have been phenomenal “super-profits” for private companies like Barrick Gold, Goldcorp and Yamana, who netted a combined $2.8-billion windfall in 2012 from their operating mines, according to the authors. (Canadian mining companies earned a total of $19.3 billion that year.) Between 1998 and 2013, the authors calculate that these three companies averaged a 45% rate of profit on their operating mines when the Canadian economy’s average rate of profit was 11.8%.

Compare this to Canada’s miserly Latin American development aid expenditures of $187.7 million in in 2012—a good portion of this destined for training, infrastructure and legislative reform programs intended to support the Canadian mining sector. Or consider that the same year $2.8 billion was taken out of Latin America by three Canadian mining firms, remittances back to the region from migrants living in Canada totalled only $798 million (much more than Canadian aid).

Without spelling out the long-term social and environmental costs of these operations—costs that are externalized onto affected communities—or going into the problematic ways that private investment and Canadian aid can be used to condition local support for a mine project, Gordon and Webber posit that “super-profits” may be precisely the “Canadian interests” the government’s foreign policy apparatus is set up to defend—not authentic community development, lasting quality jobs or a reliable macroeconomic model.

State support for “militarized neoliberalism”

The argument that the role of the Canadian state is “to create the best possible conditions for the accumulation of profit” is central to Gordon and Webber’s book. From the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) down, Canadian agencies and foreign policy have been harnessed to justify “Canadian plunder of the wealth and resources of poorer and weaker countries.” Furthermore, they write, Canada has actively supported the advancement of “militarized neoliberalism” in the region, as country after country has returned to extractive industry, and export-driven and commodity-fuelled economic growth, which comes with high costs for affected-communities and other macroeconomic risks:

The extractive model of capitalism maturing in the Latin American context today does not only involve the imposition of a logic of accumulation by dispossession, pollution of the environment, reassertion of power of the region by multinational capital, and new forms of dependency. It also, necessarily and systematically involved what we call militarized neoliberalism: violence, fraud, corruption, and authoritarian practices on the part of militaries and security forces. In Latin America, this has involved murder, death threats, assaults and arbitrary detention against opponents of resource extraction.

The rapid and widespread granting of mining concessions across large swaths of territory (20% of landmass in some countries), regardless of who lives there or how they might value different lands, water or territory, has provoked hundreds of conflicts and powerful resistance from the community level upward. In reaction, and in order to guarantee foreign investment, in many parts of the region states have intensified the demonization and criminalization of land- and environment-defenders, while state armed forces have increased their powers, and para-state armed forces expanded their territorial control.

Far from being a countervailing force to this trend, the Canadian state has focused its aid, trade and diplomacy on those countries most aligned with its economic interests. It is not unusual to see public gestures of friendship or allegiance toward governments “that share [Canada’s] flexible attitude towards the protection of human rights,” such as Mexico, post-coup Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia. Meanwhile, Canada has used diverse tactics (in Venezuela and Ecuador, for example) to contain resistance and influence even modest reforms.

Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach in Honduras

One of the more detailed examples in Blood of Extraction of Canadian imperialism in Central America covers Canada’s role in Honduras following the military-backed coup in June 2009. Documents obtained from access to information requests provide new revelations and new clarity into how Canadian authorities tried to take advantage of the political opportunities afforded by the coup to push forward measures that favour big business. Once again, though other economic sectors are discussed, mining takes centre stage.

After the terrible experience of affected communities with Goldcorp’s San Martin mine (from the year 2000 onward), Hondurans successfully put a moratorium on all new mining permits pending legal reforms promised by former president José Manuel Zelaya. On the eve of the 2009 coup, a legislative proposal was awaiting debate that would have banned open-pit mining and the use of certain toxic substances in mineral processing, while also making community consent binding on whether or not mining could take place at all. The debate never happened.

Instead, shortly after the coup, and once a president more friendly to “Canadian interests” was in place following a questionable election, the Canadian lobby for a new mining law went into high gear. A key goal for the Canadian government, according to an embassy memo, was “[to facilitate] private sector discussions with the new government in order to promote a comprehensive mining code to give clarity and certainty to our investments.” Another embassy record said that mining executives were happy to assist with the writing of a new mining law that would be “comparable to what is working in other jurisdictions” and developed with a resource person with whom their “ideologies aligned.”

In a highly authoritarian and repressive context, and under the deceptive banner of corporate social responsibility, the Canadian Embassy—with support from Canadian ministerial visits, a Honduran delegation to the annual meeting of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), and overseas development aid to pay for technical support—managed to get the desired law passed in early 2013, lifting the moratorium. Then, in June 2014, with full support from Liberals and Conservatives in the House of Commons and the Senate, Canada ratified a free trade agreement with Honduras, effectively declaring that “Honduras, despite its political problems, is a legitimate destination for foreign capital,” write Gordon and Webber.

Contrary to the prevailing theory in Canada that sustaining and increasing economic and political engagement with such a country will lead to improved human rights, the social and economic indicators in Honduras have gotten worse. Since 2010, the authors note, Honduras has the worst income distribution of any country in Latin America (it is the most unequal region in the world). Poverty and extreme poverty rates are up by 13.2% and 26.3%, respectively, after having fallen under Zelaya by 7.7% and 20.9%. Compounding this, Honduras is now the deadliest place to fight for Indigenous autonomy, land, the environment, the rule of law, or just about any other social good.

A strategy of containment in Correa’s Ecuador

In contrast to how Canada has more strongly aligned itself with Latin American regimes openly supportive of militarized neoliberalism, the experience in Ecuador under the administration of President Rafael Correa illustrates how Canada considers “any government that does not conform to the norms of neoliberal policy, and which stretches, however modestly, the narrow structures of liberal democracy…a threat to democracy as such.”

In the chapter on Ecuador, Gordon and Webber provide a detailed account of Canada’s “whole-of-government” approach to containing modest reforms advanced by Correa and undermining the opposition of affected communities and social movements to opening the country to large-scale mining. A critical moment in this process occurred in mid-2008, when a constitutional-level decree was issued in response to local and national mobilizations against mining. The Mining Mandate would have extinguished most or all of the mining concessions that had been granted in the country without prior consultation with affected communities, or that overlapped with water supplies or protected areas, among other criteria. It also set in place a short timeline for the development of a new mining law.

The Canadian embassy immediately went to work. Meetings between Canadian industry and Ecuadorian officials, including the president, were set up to ensure a privileged seat at talks over the new mining law. Gordon and Webber’s review of documents obtained under access to information requests further reveals that the embassy even helped organize pro-mining demonstrations together with industry and the Ecuadorian government. Embassy records describe their intention “to create sympathy and support from the people” as part of a “a pro-image campaign,” which included “an aggressive advertisement campaign, in favour of the development of mining in Ecuador.” Meanwhile, behind closed doors, industry threatened to bring international arbitration against Ecuador under a Canada–Ecuador investor protection agreement (which a couple of investors eventually did).

Ultimately, the authors conclude, Canadian diplomacy “played no small part” in ensuring that the Mining Mandate was never applied to most Canadian-owned projects, and that a relatively acceptable new mining law was passed in early 2009. While embassy documents show the Canadian government considered the law useful enough to “open the sector to commercial mining,” it was still not business-friendly enough, particularly because of the higher rents the state hoped to reap from the sector. As a result, the embassy kept up the pressure, including using the threat of withholding badly needed funds for infrastructure projects until mining company concerns were addressed and dialogue opened up with all Canadian companies.

Not discussed in The Blood of Extraction, we also know the pressure from Canadian industry continued for many more years, eventually achieving reforms, in 2013, that weakened environmental requirements and the tax and royalty regime in Ecuador. Meanwhile, as the door opened to the mining industry, mining-affected communities and supporting organizations were feeling the walls of political and social organizing space cave in, as they faced persistent legal persecution and demonization from the state itself, while the serious negative impacts of the country’s first open-pit copper mine started to be felt.

Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy”

The Blood of Extraction is a helpful portrait of “the drivers behind Canadian foreign policy.” Gordon and Webber lay bear “a systematic, predictable, and repeated pattern of behaviour on the part of Canadian capital and the Canadian state in the region,” along with its systemic and almost predictable harms to the lives, wellbeing and desired futures of Indigenous peoples, communities and even whole populations. They call it Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy.”

The problem is not Goldcorp or HudBay Minerals, Tahoe Resources or Nevsun. These companies are all symptoms of a system on overdrive, fuelling the overexploitation of land, communities, workers and nature to fill the pockets of a small transnational elite based principally in the Global North. If we cannot see how deeply enmeshed Canadian capital is with the Canadian state—how “Canadian interests” are considered met when Canadian-based companies are making super-profits, even through violent destruction—we cannot get a sense of how thoroughly things need to change.

Jen Moore is the Latin America Program Coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, working to support communities, organizations and networks in the region struggling with mining conflicts.

This article was published in the November/December 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 12, 2016 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Brett Spencer / Intercontinental Cry

On Monday, November 7th, the day after Nicaragua’s primary elections, supporters of the Miskito indigenous party, Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka, or Sons of Mother Earth (YATAMA), took to the streets of Puerto Cabezas to celebrate a regional victory for Indigenous Peoples. It had just been announced that Brooklyn Rivera, the leader of YATAMA, had won political office.

Supporters of YATAMA celebrate news of victory during a speech by Brooklyn Rivera. Photo: Brett Spencer

Local polls concluded that YATAMA had secured the victory despite numerous allegations of electoral fraud. Nine out of twelve people IC interviewed at four polling stations in Puerto Cabezas reported the fraud in favor of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), led by Nicaragua’s current president, Daniel Ortega.

“There is serious doubt about the transparency, the cleanliness and the purity of this process,” said Mr. Rivera. Other than YATAMA, “there is no real opposition” and “no international observation of the elections,” he concluded.

Despite these allegations, YATAMA supporters planned to march across the town at 2:00 pm. However, it was learned around that time that the victory would not be acknowledged until the vote was recounted in Managua, without the presence of YATAMA officials.

The announcement created a sense of unease as the streets filled with Miskito of all demographics in support of Brooklyn Rivera’s re-election as a deputy in the National Assembly.

Mr. Rivera was ousted from office in September of 2015, following a rise in violence over an endemic land conflict between the Miskito and Sandinista settlers known to the Miskito as colonos.

Puerto Cabezas reacts to news of a YATAMA victory. Photo: Brett Spencer

The indigenous population swelled the streets with gracious enthusiasm following an optimistic speech by Mr. Rivera. However, shortly after the start of the march, police began to line the main street in riot gear, preventing the march from continuing.

Miskito youth began throwing stones at the officers and the police began firing rubber bullets into the crowd, provoking more outrage. A group of YATAMA supporters overtook the governor’s office, removing office equipment including computers. The crowd began to compile makeshift weapons to fend off the police, who began using tear gas in an attempt to disperse the crowd.

Many of the women and children took safety in a bar overlooking the conflict, only to have tear gas thrown at them by the police officers.

Police fire rubber bullets at Miskito youth: Brett Spencer

“This was suppose to be a peaceful march, but the police started instigating,” said Walt, who works at the bar where we took safety. “But the people have to march to get results around here, otherwise the result would not be the same.”

YATAMA’s supporters eventually overtook the police around 6:00 pm, who retreated to the police station. After the sun had set, a group of Miskito youth, angry with the police for stopping the march, broke into several shops owned by Sandinista supporters.

Photo: Brett Spencer

The following morning, the local Sandinista radio station, Bilwi Stereo, blamed the conflict on the participation of foreigners, discrediting the power and agency of YATAMA’s wide support base. Puerto Cabezas became militarized overnight, with trucks of heavily armed soldiers patrolling the empty streets.

The streets remained calm but ill at ease, as relations between the Miskito and the Sandinista government continue to deteriorate. “We need something better for our people,” said Hector Williams, the Wihta Tara, or “Great Judge” of the Miskito separatist movement. “This is La Moskitia, it is not Nicaragua.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 5, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured Image: Police clashes. Credit: Frenadeso

By Richard Arghiris / Intercontinental Cry

Panama’s national police left approximately 20 indigenous Ngäbe protesters injured last week in what one medic described as an “absurd and irresponsible act.”

The protesters, all residents of Gualaquita, mobilized against the Barro Blanco hydro dam after the project’s owner and operator, Honduran-based Generadora del Istmo (GENISA) began flooding the Tabasará River basin with blessings from the government.

It didn’t take long for Ngäbe communities within the basin to suffer the consequences. In the community of Kiad, local road connections were washed away by the flood waters leaving entire families geographically isolated. Houses were also submerged by the rising waters, along with significant archaeological sites in the region.

Submerged houses. Photo: Ricardo Miranda

All of the Tabasará communities affected by the flood waters were excluded from the talks that led to the agreement. They also didn’t endorse the new agreement in any way, shape, or form.

The Ngäbe community of Gualaquita is located outside of the affected area, but they too declined to endorse the agreement.

For the protesters, who are members of the Mama Tatda religion, the Tabasará River is a holy site that needs to be protected. The river is also home to ancient petroglyphs and unique Ngäbe cultural centers. To the protesters, their loss or destruction represents a violation of religious freedom.

The government wasted little time responding to the protesters.

According to a preliminary report by one of the country’s largest trade unions – the National Front for the Defense of Economic and Social Rights (Frenadeso) – around 2pm on Aug 24, 2016, some 500 police officers arrived to crush the opposition.

Police in Gualaquita. Credit: Frenadeso

Speaking to Frenadeso, Dr. Manuel Pardo, who attended to the injured in the aftermath of the assault, called the protesters “victims of police aggression,” stating, “There was a clear and flagrant violation of the fundamental human rights of the community of Gualaquita.”

Dr. Manuel Pardo assesses the injured. Credit: Frenadeso

Osvaldo Jordan, director of the Alliance for Conservation and Development (ACD), told IC that the police didn’t just target the protesters. “[They] stormed into the whole community, detaining people who were not even in the protest… It was an outright occupation of the community, war style.”

Injuries that appear to have been inflicted by rubber bullets. Credit: Frenadeso

“The weapons that were used for the confrontation were rubber bullets, birdshot and pepper gas,” said Dr. Pardo during his visit to the community on Aug 28, 2016.

“The police entered the community and practically every house was ‘fumigated’ with pepper gas… we are still coughing and itchy… In addition to rubber bullets, birdshot and pepper gas, the attacks involved physical blows and kicking… The result was 20 people injured…”

Police ammunition and equipment collected in Gualaquita. Credit: unknown

Police ammunition and equipment collected in Gualaquita. Credit: unknown

Police ammunition and equipment collected in Gualaquita. Credit: unknown

Dr. Pardo went on to explain that, three of the protesters were severely wounded during the crackdown. One person may have suffered a life-changing injury to his right eye. Another, who sustained serious head trauma, was detained by police for 48 hours before receiving medical treatment in a hospital.

Some of the injured community members reportedly refused to seek help from official institutions for fear of being arrested. Dr. Pardo described this as a “lamentable” violation of their basic human right to health care.

The Frenadeso report also alleges that the police burned a Mama Tatda flag and broke into several community stores. They apparently stole food, cell phones, chargers and hundreds of dollars in cash. They are also alleged to have threatened a storekeeper with firearms and made various death threats to different people.

Adolfo Miranda was allegedly shot in his right eye by a rubber bullet. Credit: Frenadeso

Some of the protesters hit back at the police with rocks and slingshots. Several officers were injured and subsequently transported by plane for treatment in private hospitals.

In the aftermath of the clash, images of the injured protesters were circulated on social media, but government ministers initially denied their veracity.

“They are using old photos of other incidents,” Alexis Bethancourt, Minister of Security, told La Estrella newspaper. “This police force guarantees human rights.”

Subsequent on-the-scene reporting from national journalists such as Lissette Centen helped to confirm that the images were in fact real.

This photograph of journalist Lissette Centen at the scene verifies that the images were real. Credit: Frenadeso

According to a BARRO BLANCO. INFORME DDHH 22-6-16 (HRNP), the repression in Gualaquita is only the latest act of violence the Varela government has committed against Panama’s Indigenous Peoples.

According to eye-witness testimonies collected by the HRNP, on May 23, 2016, in an orchestrated prelude to the filling of the Barro Blanco reservoir, riot police descended on a Ngäbe protest camp, demolished a Mama Tata church and decapitated the community’s livestock. They rounded up some 30 protesters and held them for 36 hours without due process. Young children were among the detainees and one woman was apparently stripped naked in front of her family.

Despite clear threats to their safety, the Tabasará communities are determined to keep fighting Barro Blanco. Mass mobilizations are planned in different parts of the country for Monday September 5, 2016.

Meanwhile, the Ngäbe community of Kiad is at a critical juncture. According to Osvaldo Jordan, the waters of the reservoir are nearing the houses. “The main square can still be saved,” he said. The government just has to stop the flooding of Ngäbe land.