Clouds of Uncertainty

A web of impunity, corruption and extractivism confronts indigenous leaders in Colombia’s southwest

Featured image: A cloud hangs over Rioblanco, a Yanacona reservation in the municipality of Sotará, in Cauca, Colombia. Photo: Robin Llewellyn

by Robin Llewellyn / Intercontinental Cry

When the Colombian government signed a peace agreement with the left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in June 2016, it brought a tentative end to more than five decades of violent armed conflict. But ever since the peace accord was signed, social leaders across Colombia have been threatened and killed with alarming regularity. The province of Cauca is at the epicenter of this new wave of violence.

On March 5 of this year, a death threat was anonymously placed under the door of the Yanacona’s council hall in Rioblanco, an indigenous reservation in the municipality of Sotará, high up in the mountains of south-western Colombia. The death threat pointed squarely at the Yanacona’s Governor and Vice-governor, as well as one security guard. The message was as obscure as it was threatening; there was just one hint of who what behind it. The letter was signed, “from the assassins of Popayán.”

A year earlier, on March 2, 2016, the young governor of Rioblanco, William Alexander Oime Alarcón, was shot dead in the historic center of Cauca’s capital, the UNESCO-registered “white city” of Popayan. CCTV footage shows an attacker struggling with the governor for his bag which contained the 20 million pesos (US$6,500) that he had just withdrawn from a bank to use in social programs in the reservation, then the attacker shoots the governor in the head, back, and legs, and flees on a motorbike driven by an accomplice. Although no-one attempted to intervene the attacker did not take the bag.

The governor died that evening. He had been known to have no tolerance for corruption and had opposed the expansion of all forms of mining into the area. He had arranged an appointment with the Ombudsman for the following morning to discuss a number of death threats made against him.

The governor had been accompanied to the bank by two youths from his reservation. Immediately after the attack, one of them quietly took Oime Alarcón’s phone from his body; he would reportedly refuse to pass it over to the investigator for two weeks. During that time the slain governor would occasionally appear to be available on his Facebook account, as though his phone was being accessed by a third party.

The other youth who had been present was escorted to an office of the SIJIN (Seccional de Investigación Criminal – Colombia’s criminal investigative authority), where he saw, in an adjoining office, the attacker and his accomplice. He immediately attempted to physically attack them but was restrained and guided away to give his account of the attack. When he came out the two had left; they would not be among the eight people later arrested for the crime (and quickly released on bail). The next stage of the judicial process against them is due to begin this coming October.

The governor was to have been accompanied to the office of the Ombudsman by his cousin, Alexis Barahona, who had shared the governor’s house in Rioblanco before moving to the city of Cali to find work. It was in a visit to Cali that, in October 2015, Oime Alarcón would drink a beer with his cousin and first speak about the threats he was receiving.

“He said that they threatened him at every opportunity”, remembered Alexis. “He told me names and everything. The threats kept arriving at the house, and he simply told me these things and smiled. Two people were threatening him over some funds, some differences that existed in the council: for some money that my cousin didn’t want them to use. At the same time he told me that there were differences between himself and those who wanted to use land for mining.”

The names Oime Alarcón shared with his cousin were Mesias Chicangana and Ancizar Paz, former governors of the reservation. According to Alexis Barahona the governor didn’t take their threats seriously, believing that this “cartel de los gordos”(“cartel of the fatties”), didn’t possess the power to hurt him. The murdered governor then told his cousin that a threatening text message had referred to him as a guerrilla, and that that when coltan had been discovered above the reservation it had led to pressure from some within the community to allow exploratory mining. He also mentioned that a representative of mining interests had once arrived from outside the reservation and had asked him to sign a letter of consent to allow them to enter the territory, a request he refused. According to Alexis the two members of the “cartel de los gordos” were investigated in relation to Oime Alarcón’s killing, but were cleared of all involvement.

There had been one more thing the governor had told his cousin over a beer that evening in Cali. “I’m doing something significant, I’m trying to avoid something big happening to Rioblanco”, he had told Alexis, but he didn’t tell his cousin what it was; only the ombudsman would be told. “He didn’t want to talk to anyone else, not to the Police nor to the CRIC [Consejo Regional Indigena del Cauca / Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca].”

Immediately after Oime Alarcón’s murder, while the event was still being described as a botched robbery, indigenous leader Aida Quilcué said that investigators should consider whether recent activities that the Yanacona community had carried out in the Paramo of Barbillas had been a cause. The paramo ecosystems of the Yanacona territories are highly vulnerable to a range of environmental threats, and there the booming illegal gold mining sector has been targeted for closure by indigenous guards and indigenous authorities. “They were exercising territorial control there just eight days before” she said of the dead governor and his colleagues. “We consider that these acts could be related to the case… I don’t believe that it was a simple robbery; it’s a persecution.”

But the governor’s sister, Elizabeth Alarcón, is skeptical about automatically connecting her brother’s death with mining: she points to the death in 1995 of another leader who struggled against corruption in the reservation, Dimas Onel Majin. “The two men shared many characteristics and those responsible for both deaths have never been identified… If you look at the origin of the threats that have recently arrived, they were delivered within the community.”

In Rioblanco, she added, “there have been a number of people who have been in authority, in control of the territory, and then he [Oime Alarcón] arrived as a different type of leader, much closer to the people… He wanted to do things differently and he encountered corruption, and in Cauca there is corruption, and in his own community there is corruption.”

A mural in the square of Rioblanco remembering Alexander Oime Alarcón.

With the failure of the state investigators to reveal the authors of the killing, Elizabeth Alarcón has been left facing a host of questions related to the attack: “One could say that it’s extraordinary because they assassinated him in the very center of Popayan where one supposes that there’s a lot of security, but there was not a police response in time, there was not an ambulance response in time… people have told me that he lay there shot in the street for 15 minutes. And it’s relatively close to the hospitals. They shot him here and there is the clinic. To organize an assassination in the manner that the investigators first described, they [the authors of the attack] used many people, six or eight, and every person had their function: one to do this, one to do that. So I think that behind this there’s a lot of money and a lot of power.”

The Yanakona authorities and the CRIC responded to the threat “from the assassins of Popayan” by calling a public meeting in Rioblanco that denounced threats and attacks across Yanacona areas.

The president of the CRIC, Carlos Maca, began by decrying the presence of “new armed actors that are gathering in the [indigenous] territories, BACRIM [“bandas criminales” – ‘criminal bands’ that resemble former or current paramilitary groups such as the Gaitanistas/Urabeños, Aguilas Negras, and Rastrojos] that affect the territories, they come to systematically violate human rights; they never cease to threaten our leaders, they carry out selective and extra-judicial killings of social leaders – not just against indigenous but also against Afro-Colombian and campesino leaders. But the government doesn’t want to accept this reality, nor the commissions for human rights that, in a similar manner, disregard the organization of these new armed actors.”

Outside the meeting hall, vast clouds obscured the surrounding mountainsides, only occasionally breaking to allow a view of the emerald-green slopes beyond. Across Cauca, criminal impunity rates stand at over 90%, cloaking the identities not just of those who were involved in the attack against Governor Alarcón, but also of the identities of the armed groups that have sprung up across the region. But as the number of threats and the number of killings of social leaders in Cauca have surpassed that in every other province of Colombia, analysts are pointing to several key dynamics.

In May 2017 the Pacifista! website noted that “Ten of the 35 leaders killed in Colombia since the beginning of December 2016 died in Cauca, almost all in broad daylight and in populated areas”. They found that among the principal causes of the deaths was the entrance of new criminal power structures into areas abandoned by the FARC following their demobilization. These groups included the ELN guerrillas as well as groups of what they called ‘post-demobilization paramilitaries’ – organizations that had grown out of the officially disbanded AUC(“United Self-defense Forces” – right-wing paramilitaries that had supported the state’s crackdown on guerrillas while also stealing large stretches of land). The authors drew on a report from the Ombudsman entitled, Violence and threats against social leaders and human rights defenders, that said these new armed groups have particularly “threatened community leaders and inhabitants that oppose both illegal and large-scale mining.”

The website also mentioned the prevalence in Cauca of the coca industry, the deadly continuation of the land conflict between indigenous Nasa communities and the sugar industry, and the stigmatization and subsequent attacks against activists linked to the CRIC and to the left-wing Marcha Patriotica political movement, visible in the many pamphlets produced under the claimed authorship of the Aguilas Negras.

Others support the importance of the mining sector in driving the violence. The CRIC’s human rights team was in attendance at the meeting in Rioblanco, and Maria Ovidia Palechor reiterated that the social leaders killed in the renewed wave of killings have been “men and women who have said ‘No to mining. They have said “no to mega-projects’”.

It remains difficult to confidently attribute responsibility for the deaths or to see past the clouds of uncertainty that Colombia’s extreme criminal impunity rate has created. Do the dynamics explored above alone explain how the killers of Oime Alarcón knew he was about to testify to the Ombudsman? Or that he would be withdrawing money from a specific bank at a specific time? And do they alone explain why his phone was taken from him as he lay dying in the street?

It’s possible that we may never know, but returning to the theme of general dynamics of criminality may at least be helpful in understanding the wave of violence that has claimed the lives of other social leaders. What is the illegal mining sector in Cauca that many have seen as responsible for the governor’s death, and how does it relate to other political and economic interests in the region?

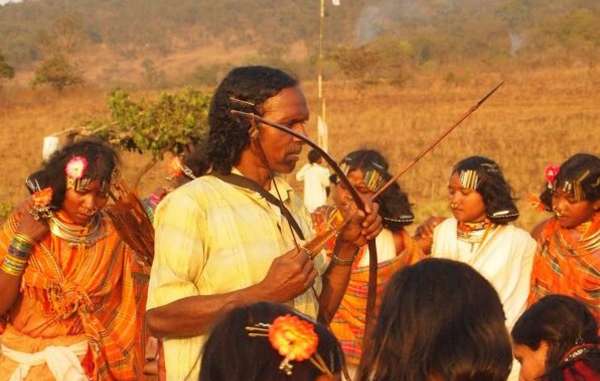

At the public meeting in Rioblanco, the governors of each community sat in the front row of the assembly holding their staffs of office, surrounding a chakana, a pre-Colombian cross laid out on the floor symbolizing Yanacona philosophy and spirituality. In the other seats and around the vast doorway gathered members of the community, one of whom announced his concern with the delay in advancing the investigation of Oime Alarcón, and recommending that another state investigator should take control of the case.

Others spoke more broadly about the history of violent conflict that was affecting the region, and condemned state institutions for their lack of interest and engagement, visible again in the failure of state officials to attend the event. Almost all the attendees wore heavy woolen ruanas against the cold, including the head governor of the Yanacona People, Ferley Quintero, who presented to the audience the measures being taken to advance their security: “The Yanacona People, their authorities and the community, have been able to advance actions of peace that enable us to live harmoniously as a people in our territory and to demand that we be respected by the armed groups. We are fortifying the position of the indigenous guards in defending our territory, in preventing the consumption of alcohol in the territory, in preventing the cultivation of coca and marijuana, and in disarming members of the community. But we have seen our efforts countered by the violation of our right to free, prior and informed consent through the installation of a High Mountain Battalion in our territory which represents a social and territorial disequilibrium, and additionally we’re threatened by the mining and energy policy that the government is forcing into our territories.”

Photo: Robin Llewellyn

Outside the hall, IC asked a member of the human rights team of the CRIC how mining represented a threat to their communities:

“In the indigenous territories there’s one problem of illegal mining, and there’s another in the form of legal mining, carried out by the multinationals. The national government is facilitating these dynamics through providing mining titles. In relation to the multinationals the government doesn’t want to accept that paramilitarism is active today in Colombia, and logically these threats come from that side because the BACRIM and the paramilitaries are returning and they, like before, are protecting the wealth and property of the rich. The other illegal mining is very well-organized, and is arriving to the rivers and mountains where there is evidence of gold, and they threaten the communities, the indigenous authorities, and the indigenous guards.”

Nelson Cuspián Jiménez, Vice-Governor of the indigenous council of Frontino, La Sierra, was also in attendance, and he told IC: “In the year 2006 Anglo Gold Ashanti arrived in the community, but thanks to the CRIC y the Grand Council of the Yanacona People, actions were organized to protect the territory and its communities. AngloGold had initiated its works without exercising prior consultation as demanded by the legal norms. But then last week that they would enter again “con toda” (with everything). We are worried that as indigenous, Afro-Colombian and campesino communities we’ll be displaced from our territories, endangering the elderly, children, and women. It would equate to the termination of the indigenous community. The state should assert the relevance of prior consultation.”

In Frontino, the Vice-Governor continued, “there is illegal mining, the gold-panners have used pressure hoses that have caused environmental damage for a number of years, no such ‘artesian mining’ should be done. The legal and illegal mining is carried out by people from outside, but also some from the campesinocommunities of the region. But the threats related to mining always come from outside.”

The explosion in illegal mining has spread across Cauca only in the last decade, according to journalist Moritz Tenthoff: “The gold fever, woken in 2008 by the financial crisis in speculative capital, increased fivefold the price of the metal between 2002 and 2010. Although in Cauca there was no company exploiting gold until that date, the production of gold has increased, according to the Sistema de Información Minero Colombiano (Information System of Colombian Mining – Simco), in a vertiginous manner, passing 621.54 kilos in 2008 to 3,544.39 kilos in 2013.”

The government has, according to the Colombian writer Alfredo Molano, exacerbated the problem. He spoke out in 2012 over the impact that Resolution 0045 would have. The Act, passed by the National Agency of Mining in June 2012, created vast new ‘strategic areas’ of mining, and would undoubtedly cause, according to Molano: “thousands of large and small miners to prepare expeditions to take possession of the ‘strategic reserve areas’ located in the few regions still preserving indigenous and black cultures, forests, rivers and wetlands. Who is going to prevent that mass of miners from invading the 22 million hectares and contaminating rivers and streams with mercury and cyanide, and from buying indigenous and municipal authorities? Moreover, when they arrive they will be giving the guerrillas and paramilitary commanders tips to provide the miners with a security service.”

The threats quickly ensued, some of which correspond with the entrance of the mining sector in various communities: The Comité de Integración del Macizo Colombiano (Committee for the Integration of the Colombian Massif) announcedthat in 2013 and 2014: “Environmentalist, authorities and social leaders of the Colombian Massif denounce how in the last weeks, they have been the victims of constant followings, threats, and harassments for defending their territory and rivers from large scale and illegal mining that is being developed in Cauca.”

Oime Alarcón’s successor as governor of Rioblanco is Juan Buenaventura Yangana. He asserted that the community remained in the dark over the identity of the killers: “We can’t truly confirm which are the sources of the criminal action that took the life of our governor last year.”

IC asked his position on mining: “We don’t take part in mining projects because they destroy our Mother Earth: they fill her with pollution, with cyanide, with all the chemicals that one has to use in mining. Mining also creates violence because it generates a lot of ready money, it creates violence and prostitution. What one has to see in relation to resources of money is that they generate deaths. For the indigenous Peoples, the places where they have detected precious metals have to be respected as sacred sites as we have determined them, and they are not there to enrich but to maintain as something sacred in our Mother Earth.”

In such words, one can perceive the vital elements of a conflict, whether or not such dynamics were at play in the specific case of the former governor’s death: the wave of illegal mining meeting such perspectives with many of the threats and attacks that have taken the region to the center of the current epidemic of violence.

The wave has also crowded many of the riversides of the department with yellow earth-movers, notwithstanding the illegality of their presence, nor their proximity to the main highways along which daily pass functionaries of the institutions of state. To a member of the CRIC who asked not to be identified, this cohabitation testifies not only to the bribes and the intimidation that have deterred mayors and governors from enforcing strict legal controls on the transport of earthmovers, but also to a tacit support by the state and multinational companies for the illegal mining sector. The violence and pollution caused by illegal miners weakens the social fabric of communities, which are then less able or less inclined to resist the entrance of the multinationals. The activist claimed that people in affected areas are left desperate, and more inclined to believe the promise of reduced environmental contamination that is implicit in the slogan shared by the large-scale mining lobby and the Colombian Ministry of Mines: “minería bien hecha” – “mining well done”.

Ministry of Mines slogan “mineria bien hecha” – “mining well done”.

The vast majority of Cauca’s gold is produced today in untitled mines and then sold through commercializing companies to enter the ‘legal’ markets in Cali and Medellin. Moritz Tenthoff was able to secure an interview with one of the kingpins in the illegal mining sector in Cauca, Alexander Duque Builes, who attributed the birth of the sector to the policies of ex-President Alvaro Uribe Velez: “When the ‘democratic security’ policy arrived [Uribe’s pursuit of a military crack-down against the guerrillas that relied on the involvement of paramilitary groups] we saw an opportunity to grow and strengthen. Cauca has immense mining potential, the mining zones are large, only the issue of public order has been the cause of the slow growth that Cauca has had.”

The majority of areas that today produce gold in Cauca are frequented by illegal armed groups including the ELN and BACRIM/paramilitaries, that charge protection money from the miners who sometimes have been displaced from failing sections of the rural economy. These payments then feed into other interests of criminal actors, including narco-trafficking and extortion, all of which serve to challenge the territorial control exercised by indigenous authorities.

Miller Hormiga, lawyer for the CRIC, represents those victimized by the killing of Oime Alarcón, and he attempted to explain why the impunity rate in Cauca is so high: “The Colombian justice system lacks the strong tools needed to guide its investigations. We sometimes overlook the technological aspect of investigative agencies, of the judicial police, which is still not at a good international standard. We still have many deficiencies, a great lack in personnel, the impossibility of reaching all territories, the context of risk that causes witness not to participate in an opportune way, the great accumulation of cases that one lawyer and judge will face… all of these things together generate a climate that favors impunity: that many cases don’t succeed in establishing who were the material and intellectual authors of the acts. It’s an enormous difficulty.

When asked about the impact mining has had on Cauca, Hormiga said that, “One of the things that we have always viewed with suspicion is that the activities of illegal mining precede the interests or activities of legal mining of a national or international character. This worries us. And what we do know is that there is interest from outside in pursuing mining in indigenous territories, and we have seen that mining truly represents a potent risk for the lives of indigenous Peoples.”

Threats continue to be made across indigenous Cauca. Just a few days ago, ICreturned with a voice-recorder that went unused because a victim wouldn’t talk to the media. Was mining involved? Probably, but without being able to conduct interviews the clouds of uncertainty continue to conceal vital details. In relation to justice, the impunity that Hormiga described could prove to be as potent a threat to the lives of Indigenous Peoples as the boom in illegal mining, and could it be that a synergy between these two dynamics was at play behind the actions of the “assassins of Popayan”.