by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 25, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

by Survival International

A mining company in India has renewed its efforts to start mining on the sacred hills of the Dongria Kondh people, despite previous defeat in the Supreme Court, and determined opposition by the tribe.

The Dongria Kondh consider the Niyamgiri Hills to be sacred and have been dependent on and managed them for millennia. Despite this the Odisha Mining Corporation (OMC), which previously partnered with British-owned Vedanta Resources, is once again attempting to open a bauxite mine there.

In February this year, OMC sought permission from India’s Supreme court to re-run a ground breaking referendum, in which the Dongria tribe had resolutely rejected large-scale mining in their hills. This petition was thrown out by the Supreme Court in May.

India’s Business Standard reported recently that OMC is gearing up for yet another attempt to mine, after getting the go-ahead from the government of Odisha state.

Dongria leader Lodu Sikaka has said: ”We would rather sacrifice our lives for Mother Earth, we shall not let her down. Let the government, businessmen, and the company argue and repress us as much as they can, we are not going to leave Niyamgiri, our Mother Earth. Niyamgiri, Niyam Raja, is our god, our Mother Earth. We are her children.”

For tribal peoples like the Dongria, land is life. It fulfills all their material and spiritual needs. Land provides food, housing and clothing. It’s also the foundation of tribal peoples’ identity and sense of belonging.

The theft of tribal land destroys self-sufficient peoples and their diverse ways of life. It causes disease, destitution and suicide.

The Dongria’s rejection of mining at 12 village meetings in 2013, led the Indian government to refuse the necessary clearances to mining giant Vedanta Resources. This was viewed as a heroic David and Goliath victory over London-listed Vedanta and the state-run OMC.

Only the Dongria’s courageous defence of their sacred hills has stopped a mine which would have devastated the area: more evidence that tribal peoples are better at looking after their environment than anyone else. They are the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world. Protecting their territory is an effective barrier against deforestation and other forms of environmental degradation.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

by Jen Moore / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Stories of bloody, degrading violence associated with Canadian mining operations abroad sporadically land on Canadian news pages. HudBay Minerals, Goldcorp, Barrick Gold, Nevsun and Tahoe Resources are some of the bigger corporate names associated with this activity. Sometimes our attention is held for a moment, sometimes at a stretch. It usually depends on what solidarity networks and under-resourced support groups can sustain in their attempts to raise the issues and amplify the voices of those affected by one of Canada’s most globalized industries. But even they only tell us part of the story, as Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber make painfully clear in their new book, The Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America (Fernwood Publishing, November 2016).

“Rather than a series of isolated incidents carried out by a few bad apples,” they write, “the extraordinary violence and social injustice accompanying the activities of Canadian capital in Latin America are systemic features of Canadian imperialism in the twenty-first century.” While not completely focused on mining, The Blood of Extraction examines a considerable range of mining conflicts in Central America and the northern Andes. Together with a careful review of government documents obtained under access to information requests, Gorden and Webber manage to provide a clear account of Canadian foreign policy at work to “ensure the expansion and protection of Canadian capital at the expense of local populations.”

Fortunately, the book is careful, as it must be in a region rich with creative community resistance and social movement organizing, not to present people as mere victims. Rather, by providing important context to the political economy in each country studied, and illustrating the truly vigorous social organization that this destructive development model has awoken, the authors are able to demonstrate the “dialectic of expansion and resistance.” With care, they also show how Canadian tactics become differentiated to capitalize on relations with governing regimes considered friendly to Canadian interests or to try to contain changes taking place in countries where the model of “militarized neoliberalism” is in dispute.

The spectacular expansion of “Canadian interests” in Latin America

We are frequently told Canadian mining investment is necessary to improve living standards in other countries. Gordon and Webber take a moment to spell out which “Canadian interests” are really at stake in Latin America—the principal region for Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) in the mining sector—and what it has looked like for at least two decades: “liberalization of capital flows, the rewriting of natural resource and financial sector rules, the privatization of public assets, and so on.”

Cumulative CDIA in the region jumped from $2.58 billion in stock in 1990 to $59.4 billion in 2013. These numbers are considerably underestimated, the authors note, since they do not include Canadian capital routed through tax havens. In comparison, U.S. direct investment in the region increased proportionately about a quarter as much over the same period. Despite having an economy one-tenth the size of the U.S., Canadian investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is about a quarter the value of U.S. investment, and most of it is in mining and banking.

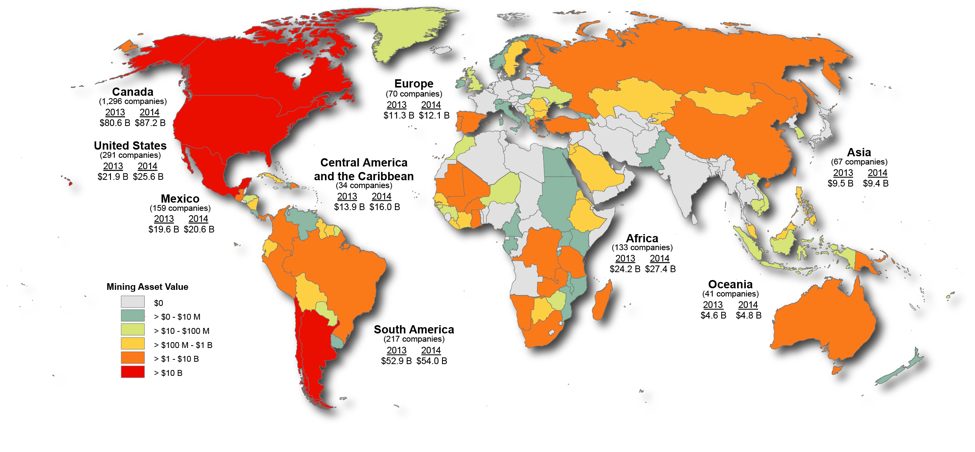

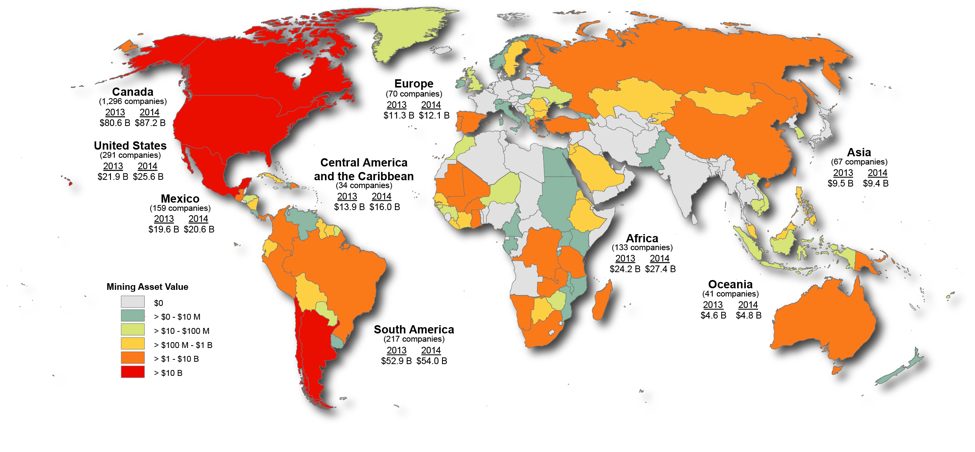

Canadian mining investment abroad

To cite a few of the statistics from Gordon and Webber’s book, Latin America and the Caribbean now account for over half of Canadian mining assets abroad (worth $72.4 billion in 2014). Whereas Canadian companies operated two mines in the region in 1990, as of 2012 there were 80, with 48 more in stages of advanced development. In 2014, Northern Miner claimed that 62% of all producing mines in the region were owned by a company headquartered in Canada. This does not take into consideration that 90% of the mining companies listed on Canadian stock exchanges do not actually operate any mine, but rather focus their efforts on speculating on possible mineral finds. This means that, even if a mine is eventually controlled by another source of private capital, Canadian companies are very frequently the first face a community will see in the early stages of a mining project.

The results have been phenomenal “super-profits” for private companies like Barrick Gold, Goldcorp and Yamana, who netted a combined $2.8-billion windfall in 2012 from their operating mines, according to the authors. (Canadian mining companies earned a total of $19.3 billion that year.) Between 1998 and 2013, the authors calculate that these three companies averaged a 45% rate of profit on their operating mines when the Canadian economy’s average rate of profit was 11.8%.

Compare this to Canada’s miserly Latin American development aid expenditures of $187.7 million in in 2012—a good portion of this destined for training, infrastructure and legislative reform programs intended to support the Canadian mining sector. Or consider that the same year $2.8 billion was taken out of Latin America by three Canadian mining firms, remittances back to the region from migrants living in Canada totalled only $798 million (much more than Canadian aid).

Without spelling out the long-term social and environmental costs of these operations—costs that are externalized onto affected communities—or going into the problematic ways that private investment and Canadian aid can be used to condition local support for a mine project, Gordon and Webber posit that “super-profits” may be precisely the “Canadian interests” the government’s foreign policy apparatus is set up to defend—not authentic community development, lasting quality jobs or a reliable macroeconomic model.

State support for “militarized neoliberalism”

The argument that the role of the Canadian state is “to create the best possible conditions for the accumulation of profit” is central to Gordon and Webber’s book. From the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) down, Canadian agencies and foreign policy have been harnessed to justify “Canadian plunder of the wealth and resources of poorer and weaker countries.” Furthermore, they write, Canada has actively supported the advancement of “militarized neoliberalism” in the region, as country after country has returned to extractive industry, and export-driven and commodity-fuelled economic growth, which comes with high costs for affected-communities and other macroeconomic risks:

The extractive model of capitalism maturing in the Latin American context today does not only involve the imposition of a logic of accumulation by dispossession, pollution of the environment, reassertion of power of the region by multinational capital, and new forms of dependency. It also, necessarily and systematically involved what we call militarized neoliberalism: violence, fraud, corruption, and authoritarian practices on the part of militaries and security forces. In Latin America, this has involved murder, death threats, assaults and arbitrary detention against opponents of resource extraction.

The rapid and widespread granting of mining concessions across large swaths of territory (20% of landmass in some countries), regardless of who lives there or how they might value different lands, water or territory, has provoked hundreds of conflicts and powerful resistance from the community level upward. In reaction, and in order to guarantee foreign investment, in many parts of the region states have intensified the demonization and criminalization of land- and environment-defenders, while state armed forces have increased their powers, and para-state armed forces expanded their territorial control.

Far from being a countervailing force to this trend, the Canadian state has focused its aid, trade and diplomacy on those countries most aligned with its economic interests. It is not unusual to see public gestures of friendship or allegiance toward governments “that share [Canada’s] flexible attitude towards the protection of human rights,” such as Mexico, post-coup Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia. Meanwhile, Canada has used diverse tactics (in Venezuela and Ecuador, for example) to contain resistance and influence even modest reforms.

Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach in Honduras

One of the more detailed examples in Blood of Extraction of Canadian imperialism in Central America covers Canada’s role in Honduras following the military-backed coup in June 2009. Documents obtained from access to information requests provide new revelations and new clarity into how Canadian authorities tried to take advantage of the political opportunities afforded by the coup to push forward measures that favour big business. Once again, though other economic sectors are discussed, mining takes centre stage.

After the terrible experience of affected communities with Goldcorp’s San Martin mine (from the year 2000 onward), Hondurans successfully put a moratorium on all new mining permits pending legal reforms promised by former president José Manuel Zelaya. On the eve of the 2009 coup, a legislative proposal was awaiting debate that would have banned open-pit mining and the use of certain toxic substances in mineral processing, while also making community consent binding on whether or not mining could take place at all. The debate never happened.

Instead, shortly after the coup, and once a president more friendly to “Canadian interests” was in place following a questionable election, the Canadian lobby for a new mining law went into high gear. A key goal for the Canadian government, according to an embassy memo, was “[to facilitate] private sector discussions with the new government in order to promote a comprehensive mining code to give clarity and certainty to our investments.” Another embassy record said that mining executives were happy to assist with the writing of a new mining law that would be “comparable to what is working in other jurisdictions” and developed with a resource person with whom their “ideologies aligned.”

In a highly authoritarian and repressive context, and under the deceptive banner of corporate social responsibility, the Canadian Embassy—with support from Canadian ministerial visits, a Honduran delegation to the annual meeting of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), and overseas development aid to pay for technical support—managed to get the desired law passed in early 2013, lifting the moratorium. Then, in June 2014, with full support from Liberals and Conservatives in the House of Commons and the Senate, Canada ratified a free trade agreement with Honduras, effectively declaring that “Honduras, despite its political problems, is a legitimate destination for foreign capital,” write Gordon and Webber.

Contrary to the prevailing theory in Canada that sustaining and increasing economic and political engagement with such a country will lead to improved human rights, the social and economic indicators in Honduras have gotten worse. Since 2010, the authors note, Honduras has the worst income distribution of any country in Latin America (it is the most unequal region in the world). Poverty and extreme poverty rates are up by 13.2% and 26.3%, respectively, after having fallen under Zelaya by 7.7% and 20.9%. Compounding this, Honduras is now the deadliest place to fight for Indigenous autonomy, land, the environment, the rule of law, or just about any other social good.

A strategy of containment in Correa’s Ecuador

In contrast to how Canada has more strongly aligned itself with Latin American regimes openly supportive of militarized neoliberalism, the experience in Ecuador under the administration of President Rafael Correa illustrates how Canada considers “any government that does not conform to the norms of neoliberal policy, and which stretches, however modestly, the narrow structures of liberal democracy…a threat to democracy as such.”

In the chapter on Ecuador, Gordon and Webber provide a detailed account of Canada’s “whole-of-government” approach to containing modest reforms advanced by Correa and undermining the opposition of affected communities and social movements to opening the country to large-scale mining. A critical moment in this process occurred in mid-2008, when a constitutional-level decree was issued in response to local and national mobilizations against mining. The Mining Mandate would have extinguished most or all of the mining concessions that had been granted in the country without prior consultation with affected communities, or that overlapped with water supplies or protected areas, among other criteria. It also set in place a short timeline for the development of a new mining law.

The Canadian embassy immediately went to work. Meetings between Canadian industry and Ecuadorian officials, including the president, were set up to ensure a privileged seat at talks over the new mining law. Gordon and Webber’s review of documents obtained under access to information requests further reveals that the embassy even helped organize pro-mining demonstrations together with industry and the Ecuadorian government. Embassy records describe their intention “to create sympathy and support from the people” as part of a “a pro-image campaign,” which included “an aggressive advertisement campaign, in favour of the development of mining in Ecuador.” Meanwhile, behind closed doors, industry threatened to bring international arbitration against Ecuador under a Canada–Ecuador investor protection agreement (which a couple of investors eventually did).

Ultimately, the authors conclude, Canadian diplomacy “played no small part” in ensuring that the Mining Mandate was never applied to most Canadian-owned projects, and that a relatively acceptable new mining law was passed in early 2009. While embassy documents show the Canadian government considered the law useful enough to “open the sector to commercial mining,” it was still not business-friendly enough, particularly because of the higher rents the state hoped to reap from the sector. As a result, the embassy kept up the pressure, including using the threat of withholding badly needed funds for infrastructure projects until mining company concerns were addressed and dialogue opened up with all Canadian companies.

Not discussed in The Blood of Extraction, we also know the pressure from Canadian industry continued for many more years, eventually achieving reforms, in 2013, that weakened environmental requirements and the tax and royalty regime in Ecuador. Meanwhile, as the door opened to the mining industry, mining-affected communities and supporting organizations were feeling the walls of political and social organizing space cave in, as they faced persistent legal persecution and demonization from the state itself, while the serious negative impacts of the country’s first open-pit copper mine started to be felt.

Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy”

The Blood of Extraction is a helpful portrait of “the drivers behind Canadian foreign policy.” Gordon and Webber lay bear “a systematic, predictable, and repeated pattern of behaviour on the part of Canadian capital and the Canadian state in the region,” along with its systemic and almost predictable harms to the lives, wellbeing and desired futures of Indigenous peoples, communities and even whole populations. They call it Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy.”

The problem is not Goldcorp or HudBay Minerals, Tahoe Resources or Nevsun. These companies are all symptoms of a system on overdrive, fuelling the overexploitation of land, communities, workers and nature to fill the pockets of a small transnational elite based principally in the Global North. If we cannot see how deeply enmeshed Canadian capital is with the Canadian state—how “Canadian interests” are considered met when Canadian-based companies are making super-profits, even through violent destruction—we cannot get a sense of how thoroughly things need to change.

Jen Moore is the Latin America Program Coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, working to support communities, organizations and networks in the region struggling with mining conflicts.

This article was published in the November/December 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 6, 2016 | Mining & Drilling

Featured image: Many contacted Matsés have expressed opposition to any efforts to contact their uncontacted neighbors, or to explore for oil in their territory. © Survival International

by Survival International

Survival International has learned that the Peruvian government is developing a “Master Plan” for a new national park that could pave the way for large-scale oil exploration. This will threaten the lives and lands of several uncontacted tribes.

The area, known in Spanish as the Sierra del Divisor [“Watershed Mountains”], is part of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier, the region straddling the Peru-Brazil border that is home to the largest concentration of uncontacted tribal peoples on the planet.

A new plan for the area currently being drafted by Peru’s national parks agency SERNANP could enable oil companies to enter the park. It has further been reported that the new government wants to change the law to make it even easier to open up national parks to oil and gas operations.

The Sierra del Divisor National Park was created in 2015 to protect the region. The new plan could wipe out the uncontacted Indians, not all of whom have been recognized by the authorities.

A contacted Matsés woman said: “Oil will destroy the place where our rivers are born. What will happen to the fish? What will the animals drink?”

In 2016, Canadian oil company Pacific E&P cancelled a contract to explore for oil on nearby contacted Matsés territory, in the face of stiff opposition from the tribe.

The Watershed Mountains are a unique and highly diverse environment, home to many uncontacted tribal peoples.

© Diego Perez

However, it still has a contract to explore in the Watershed Mountains.

In 2012, it conducted the first phase of exploration, which Survival International and contacted Matsés campaigned against.

The more vulnerable uncontacted members of the tribe are still at risk, and not in a position to consent or object to the project. The environment that they have depended on and managed for millennia could be destroyed.

The oil exploration process uses thousands of underground explosions along hundreds of tracks cut into the forest to determine the location of oil deposits.

Uncontacted tribes are the most vulnerable peoples on the planet. All uncontacted tribal peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected.

With a new Peruvian government in place, Survival and the indigenous organizations AIDESEP, ORPIO and ORAU are urging the government to think again.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “It’s in all our interests to fight for the land rights of uncontacted tribes, because evidence proves that tribal territories are the best barrier to deforestation. Survival is doing everything we can to secure their land for them.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 25, 2016 | Mining & Drilling, Toxification

Featured image: The San Juan River still turns a muddy orange after a heavy rain, as sediments from the Gold King Mine spill are stirred up from the bottom. Suzette Brewer

by Suzette Brewer / Indian Country Today Media Network

SHIPROCK, New Mexico—On Friday, as the Obama administration temporarily halted construction of the Dakota Access pipeline due to concerns of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, another water-related human tragedy continued to unfold within the Navajo Reservation in New Mexico.

A year after the Gold King Mine spill that turned the San Juan River bright orange with millions of gallons of toxic chemicals, Navajo families continue to struggle against the ongoing, catastrophic effects on their water supply that threaten both their health and the economic stability of an already fragile community. On a daily basis, tribal members along the San Juan River say, they are still confronting the environmental, agricultural, health and spiritual fallout from the disaster that has pushed some to the brink of despair and left many others teetering on poverty.

In August 2015, more than three million gallons of toxic acid sludge and heavy metals, including lead, mercury, cadmium, beryllium, arsenic and dozens of other dangerous contaminants, was released into the Animas River at its headwaters in Silverton, Colorado, the largest tributary to the San Juan River.

Home to Shiprock, the most populous community in the Navajo Nation, the San Juan supplies water to nearly 1,500 farms and 1,200 ranches that have been devastated in the wake of what the Navajo Nation contends was “a preventable tragedy.”

The disaster, which resulted from abandoned and poorly maintained mines, has left many tribal members depressed and fearful, saying they don’t trust that the waterways are safe for them, their crops or their livestock. This leaves hundreds of farmers and ranchers without the means to earn a living in one of the poorest regions in the United States.

Meanwhile, Navajo leaders say their communities situated along the river have been “torn apart” over whether to use the water from the San Juan for their irrigation canals, livestock and ceremonial purposes. They have been left stranded, the leaders say, with no clear answers or assurances that the river upon which they have lived and survived for thousands of years will ever be restored.

“It’s hard to even gauge the scale and significance of what the Gold King spill has done to our communities,” Shiprock Chapter president Duane Yazzie told Indian Country Today Media Network. “They began mining in the 1870s, so the net effect in the last 150 years is that these mining companies can inflict any damage they want without any liability whatsoever. Congress, who has the authority to fix this, has been asked to do so for nearly a century, but they won’t. And yet we’re left to clean up the mess.”

Experts agree that there are hundreds of abandoned mines in and around Silverton, Colorado, many of which interconnect and flow into the headwaters of the Animas River—which feeds into the San Juan and directly into the tribe’s irrigation canals. For decades, said Yazzie, it was public knowledge that the mines were being improperly managed with bulwarks that had been poorly conceived and constructed, causing a massive buildup of water pressure within the mines.

When subcontractors went in to do maintenance, the mine blew out a massive cocktail of toxic water that polluted rivers and waterways for dozens of communities downstream. The tribe, however, maintains that its communities are particularly vulnerable and the most at-risk because of their unique cultural, historical, agricultural, geographic and economic dependence on the San Juan River.

Although the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has conceded responsibility, the Navajo Nation says the agency’s response has been “slow and inadequate.” They say the mine owners continue to squabble and engage in finger-pointing and blame-shifting after one of the worst environmental disasters in U.S. history.

The ensuing domino effect of the spill has led to a bitter legal imbroglio involving the Navajo Nation, New Mexico, Colorado, the mine owners and the EPA. Subsequently, New Mexico has sued Colorado, for example, and both states have sued the EPA.

The Navajo Nation, however, infuriated by the EPA for its “reckless negligence” and its unwillingness to reimburse the tribe for the more than $2 million incurred in costs related to the catastrophe, sued the agency along with the mine owners in August. In its petition, the tribe alleges that, collectively, “Defendants failed at virtually every step, in most instances advancing their own interests,” and were negligent in their maintenance of mines that were “known and substantial risks.” The EPA did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

RELATED: Navajo Nation Sues EPA Over Gold King Mine Disaster

The Navajo Nation also named Gold King Mines, Sunnyside Gold, Kinross Gold, Harrison Western, and Environmental Restoration in the lawsuit in seeking redress for the enormous amount of economic, agricultural and cultural damage done to the Navajo communities who rely on the San Juan River for their entire way of life. The 48-page petition alleges that the EPA, its subcontractor and the mine owners “consistently acted improperly, shirked responsibility, and failed to fulfill their moral and legal obligations… [and] must be held accountable for the harms caused to the San Juan River, the Nation, and to the Navajo people.”

The damage to the Navajo communities that depend on the San Juan River, Yazzie concurs, has become incalculable.

“Indians have been expendable for a long time, it doesn’t matter what damage we’re subjected to,” said Yazzie, a hint of anger flashing in his eyes. “Our people are torn [about using the water], but what choice do we have? Just like the people from Flint, Michigan, it’s a disaster, but what choice do they have?

“The Gold King spill is so massive that we don’t even know if it’s possible to clean up.”

“Something Happened to the Water”

Allen and Bertha Etsitty were caught off guard. On August 7, 2015, two full days after the spill, the Etsittys were one their way to Shiprock when they heard over the Navajo radio station, KTNN, that “something had happened to the water.”

The Etsittys, who have been married for nearly 50 years, are retired and live on Social Security. At approximately 19 acres, theirs is one of the largest family farms on the Navajo Reservation—the income from which they use to survive throughout the year.

“We’ve been farming ever since we got married,” said Allen.

“Our parents and grandparents were farmers, too,” Bertha said, as Allen nodded. “We learned to farm from them. The river is sacred for us, it was here ever since we were kids. The river is so important to us, and it provides the food we need.”

Allen and Bertha Etsitty attend a workshop for farmers and ranchers in Shiprock, New Mexico, to get assistance in filing their EPA claims from the Gold King Mine Spill. (Photo: Suzette Brewer)

Later that day, they received a call from Martin Duncan, president of the San Juan Dineh Water Users, informing them that there had been a toxic mine spill in Colorado and that the tribe would be shutting off the main gate to the irrigation canals. That night, the Etsittys, who are in their 70s, set up camp in their fields with their son, Huron, as the three of them worked around the clock to irrigate their crops with what clean water was left before the main gate was closed.

“We flooded the fields,” said Allen. “We did everything we could do.”

Over the next several weeks, the Etsittys loaded their vehicles with 325 gallon water tanks and drove back and forth nearly 100 miles a day to get water from the tanks that had been set up by the tribe in Shiprock. All told, the elderly couple hauled more than 60,000 gallons of water in a desperate attempt to save their crops.

“We only had our regular vehicles, which aren’t built for that kind of thing,” said Allen. “We went through brakes, drums, pads, transmissions, everything, trying to keep our fields watered and save what we could.”

But it was not to be. As time dragged on and the growing season stalled, the Etsittys could only watch as their crops withered away—along with their income at fall harvest.

“Our corn didn’t even make it past the tassels. We only produced about one-quarter of what we normally grow,” Allen said, adjusting the cap on his head. “It hit us hard.”

“Our corn pollen is sacred to us for prayers and offerings,” Bertha said. “It was a loss to our traditional medicine men. Everybody was looking for corn pollen this year, and we didn’t have any.”

Allen says that prior to the disaster, they planted every square inch of their acreage with crops that included several varieties of traditional Navajo corns, squash, watermelons, cantaloupe, Navajo winter melons, and a wide variety of vegetables and fruit trees. This year, they said they did not plant the same volume because of the stigma that is now associated with crops grown with potentially contaminated water. As a result, people are buying their produce elsewhere.

“People used to come from all over the rez to buy our corn,” she said. “But now we can’t grow everything we normally would because people might not buy it, so we just planted what we could.”

Additionally, the Etsittys had to give away their pigs and sell all of their sheep, livestock and horses because they simply did not have the food and water to maintain them.

“This has been stressful for everyone here,” said Bertha, with a tired smile. “This has been very stressful for us, but we do the best we can. This River is so important to us because we need that water. But with this contamination people don’t really trust the water anymore. My grandchildren ask, ‘Grandma, where are the peaches? Where are the squash?’ We don’t have any.”

“The Dark Legacy of Mining”

Since the early 1990s, the residents of Silverton, Colorado, which had based its tourism on its historical ties to the mining industry, had vigorously rejected EPA efforts to list the area as a “Superfund site,” according to the Associated Press. Fearful that such a designation would impact the town’s tourism, Silverton and San Juan County fought federal funding and assistance, even though it would have allowed mitigation for the clean-up of toxic acid leakage and hundreds of other contaminants in what has been described as one of the “worst clusters of toxic mines” in the country.

In the subsequent decades, however, water pressure behind the cheap, poorly constructed bulkheads put in place by the now-defunct mining companies continued to build—until they inevitably burst open last year, creating an unprecedented environmental disaster. In February of this year, after national outcry over the spill, the city of Silverton and San Juan County reversed their position and asked the state of Colorado to declare the area a “disaster zone” to seek federal money for clean up.

On September 7, the EPA officially announced that Silverton will become a Superfund site under the official name of “Bonita Peak Mining District.”

RELATED: Activists, Tribes Hail EPA’s Superfund Designation for Gold King Mine

Even so, the tribe continues to suffer. Last month, the Navajo Nation Attorney General’s office hosted a workshop at the Shiprock Chapter House for local farmers and ranchers to assist them with filing their claims with the EPA. One by one, tribal members filed in and quietly took their seats in the small auditorium, hoping to get answers, legal advice—anything that might help them navigate the complicated, bureaucratic maze of a government that they feel has let them down too many times to count. The exhaustion and weariness from a year-long struggle to survive was palpable.

Ethel Branch, the attorney general for the Navajo Nation, had driven up from Window Rock to facilitate the workshop. Dressed in jeans and boots, Branch introduced herself to the small audience in Navajo. In English, she then explained that the tribe was offering this assistance out of recognition that many tribal members have no legal experience or representation and needed help with filing their claims.

Branch, who was born in Tuba City and grew up in Leupp, is a Harvard-trained lawyer and is barred in the Navajo Nation, Arizona, Oregon and Washington State. The suit against the EPA and the other defendants, she said, goes far beyond financial compensation.

“At bottom, the purpose of the litigation is to make the Navajo Nation and the Navajo people whole, to clean up our river, to restore our river to its role as a life giver and protector, and to shield us from the ongoing threat of future upstream sediment suspension and hard rock mine drainage and bursts,” Branch told ICTMN. “Our farmers and ranchers deserve to be able to continue pursuing their livelihoods undisturbed―livelihoods that trace us to our ancestors, going back to time immemorial. Our people also deserve to have the food, water and financial security they enjoyed prior to the spill.”

To that end, she says the tribe has suffered tolls on their mental, physical and spiritual health from which it will be difficult to recover. Gold King, she said, was yet another in a long list of environmental incursions on the Navajo people.

“We also want to send a strong message that the Navajo Nation is not a National Sacrifice Area,” Branch said. “Assaults on our land won’t go ignored, regardless of who commits them. This is our homeland—our sacred space—and our people will not leave it. Whatever happens to the land happens to us as a people. In the past the federal government has paid no heed to our timeless connection to our land. It has left it peppered with over 500 abandoned uranium mines and mills that continue to poison our land, our water, and our people. This is unacceptable and must stop. The filing of this lawsuit is our line in the sand saying that we will hold people accountable for their violations on Navajo land and of Navajo people.”

The Navajo Nation continues to struggle with the effects of uranium mining, among other issues related to resource extraction. (Photo: Suzette Brewer)

Branch echoes the sentiments of many tribal communities across the country who continue to suffer the deleterious effects of mining and other forms of resource extraction on their water sources and lands. Tribal scientists and environmental experts say that the primary difference between tribes and their non-Indian neighbors is that they are culturally, spiritually, historically, legally and physically connected to their lands and can be “sitting ducks” for ecological disasters.

Karletta Chief is an assistant professor and assistant specialist in the Department of Soil, Water and Environmental Sciences at the University of Arizona at Tucson. Chief, a member of the Navajo Nation from Black Mesa, became a co-principal investigator of a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to examine the exposures and risk perceptions following the Gold King Mine spill.

“It’s devastating to see the San Juan contaminated knowing all the ways our people use it,” says Chief, a graduate of Stanford University. “It just breaks my heart to hear how deeply wounded they are from the spill, not just financially but also spiritually and emotionally. It has definitely fueled me and driven me to do this work on behalf of our people.”

As a part of her NIH research, Chief has taken thousands of samples from the Navajo communities along the San Juan, including water from the river and soil from the banks and fields, as well as tap water and food, measuring varying river flows and testing for contaminants—chiefly, arsenic and lead. Additionally, she and her team of researchers have been conducting focus groups, as well as house-to-house interviews to assess the complexity of the impact of the spill on their lives.

In collaboration with the tribe, other investigators have also conducted blood and urine sampling of the Navajo residents to test for arsenic, mercury and heavy metal poisoning, the results of which are not yet completed. Other projects include a dietitian, a bio-statistician, a chemist and a social scientist, all working to establish the full measure of the disaster on the tribe.

“The object was to look at all the ways people might have been exposed and affected,” Chief said. “What we found is that there are 40 different ways that tribal members used the river. So it’s much more nuanced and complex than, say, a hiker, or someone who is using it for recreational purposes. That river is everything to these communities.”

Back in Shiprock, as the EPA claim workshop began to wind down, the simple human impact of the contamination of the San Juan was apparent. Frank John, a rancher who lives in Beclabito, had questions for the lawyers in attendance. He had filed a claim with the EPA last fall, he said, but gotten no response.

Frank John, a Navajo rancher, seeks information from attorneys in filing his EPA claim. (Photo: Suzette Brewer)

“Their lack of response is their response,” came the reply. “If they did not respond, then they have denied your claim.”

The attorney hired by the tribe to assist the attendees encouraged John to refile his claim online. But like many residents in his community, John said he has no internet, does not own a computer, and does not know how to use one, which puts him at a grave disadvantage in the modern era of instant technology.

After the workshop, John told ICTMN that after the spill, he hauled more than 250 gallons of water a day to water his cattle and sheep, to which he is now barely hanging on. He is tired and cannot understand why the EPA has ignored his claim. And he is more than a little suspicious of the federal government and its response to this and other environmental crises on the Navajo Reservation.

“Our fathers worked at the uranium mine—and they’re suffering,” he said. “And we didn’t cause this problem, but we have to live with it. And it’s ruined the river that I used to swim at when I was little, and I don’t go down there anymore.”

He stopped and looked away, wiping tears from his eyes.

“This is my home, and I’m not moving. The river is the most important thing. It’s sacred. It is our life.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 9, 2016 | Mining & Drilling

Featured image by Tony Webster / Flickr

by Steve Horn / Desmog

In the two months leading up to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ decision to issue to the Dakota Access pipeline project an allotment of Nationwide 12 permits (NWP) — a de facto fast-track federal authorization of the project — an army of oil industry players submitted comments to the Corps to ensure that fast-track authority remains in place going forward.

This fast-track permitting process is used to bypass more rigorous environmental and public review for major pipeline infrastructure projects by treating them as smaller projects.

Oil and gas industry groups submitted comments in response to the Corps’ June 1 announcement in the Federal Register that it was “requesting comment on all aspects of these proposed nationwide permits” and that it wanted “comments on the proposed new and modified NWPs, as well as the NWP general conditions and definitions.” Based on the comments received, in addition to other factors, the Corps will make a decision in the coming months about the future of the use of the controversial NWP 12, which has become a key part of President Barack Obama’s climate and energy legacy.

Beyond Dakota Access, the Army Corps of Engineers (and by extension the Obama Administration) also used NWP 12 to approve key and massive sections of both Enbridge’s Flanagan South pipeline and TransCanada’s southern leg of theKeystone XL pipeline known as the Gulf Coast Pipeline. Comments submitted as a collective by environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club, National Wildlife Federation, several 350.org local chapters, the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, Corporate Ethics International, and others, allege NWP 12 abuses by the Obama administration.

Image Credit: Regulations.gov

The groups say NWP was never intended to authorize massive pipeline infrastructure projects and that that kind of permitting authority should no longer exist. Instead, they argued in their August 1 comment, federal agencies should be required to issue Clean Water Act Section 404 permits and do a broader environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

“Simply put, the Congress did not intend the NWP program to be used to streamline major infrastructure projects like the Gulf Coast Pipeline, the Flanagan South Pipeline, and the Dakota Access Pipeline,” reads their comment. “For the reasons explained herein, we strongly oppose the reissuance of NWP 12 and its provisions that allow segmented approval of major pipelines without any project-specific environmental review or public review process.”

“Oil companies have been using this antiquated fast-track permit process that was not designed to properly address the issues of mega-projects such as the Dakota Access pipeline,” Dallas Goldtooth of the Indigenous Environmental Networkstated in the environmental groups’ press release at the closing of the NWP 12 comment period. “Meanwhile, tribal rights to consultation have been trampled and Big Oil is allowed to put our waters, air and land at immense risk. This cannot continue, it’s time for an overhaul.”

Industry groups, on the other hand, made their own arguments for the status quo.

Industry: Keep NWP 12 Alive, Presidential Campaign Ties

Many industry groups chimed in on the future of NWP 12. They included the American Petroleum Institute (API), Ohio Oil and Gas Association, West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association, Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, the Baker Botts Texas Industry Project (a who’s who of petrochemical corporations such as Halliburton, ExxonMobil, Shell Oil, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum, Kinder Morgan, and BP, as of 2008), coal and natural gas utility company Southern Company, and others.

One of those other commenters was the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance (DEPA), a lobbying and advocacy consortiumspearheaded by Harold Hamm, founder and CEO of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) giant Continental Resources, as well asenergy aide to the Donald Trump presidential campaign and potential future U.S. Secretary of Energy.

Continental Resources, as reported by DeSmog, will send some of its oil through Dakota Access and previously signed a shipping contract for the Keystone XL pipeline.

“DEPA applauds the Corps for its efforts to reissue the NWPs as they are an important regulatory vehicle to authorize activities that have minimal individual and cumulative adverse environmental effects under the Clean Water Act, Section 404 Program,” wrote DEPA. “These permits are critical to DEPA’s members in their day to day operations.”

Another commenter was Berkshire Hathaway Energy, a “most of the above” energy sources utility company (including coal and natural gas) owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway holding company. Buffett serves as a fundraiser for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

“Berkshire Hathaway Energy supports the Corps’ intention to issue NWPs,” wrote Berkshire Hathaway Energy. “The continued implementation of the NWPs is essential to the ongoing operation of Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s businesses — particularly in circumstances when timely service restoration is critical.”

Obama “Climate Test” Guidelines

On August 1, 2016, the day the commenting period closed for the future of NWP 12 and just days after the Army Corps issued a slew of NWP 12 determinations for Dakota Access, the Obama White House’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) issued a 34-page guidance memorandum, which could have potential implications for the environmental review of projects like Dakota Access.

That memo, while non-binding, calls for climate change considerations when executive branch agencies weigh what to do about infrastructure projects under the auspices of NEPA.

“Climate change is a fundamental environmental issue, and its effects fall squarely within NEPA’s purview,” wrote CEQ. “Climate change is a particularly complex challenge given its global nature and the inherent interrelationships among its sources, causation, mechanisms of action, and impacts. Analyzing a proposed action’s GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions and the effects of climate change relevant to a proposed action — particularly how climate change may change an action’s environmental effects — can provide useful information to decision makers and the public.”

NWP 12 does not receive mention in the memo. Neither does Dakota Access, Keystone XL, nor Flanagan South.

The non-binding guidance, which some have pointed to as an example of the Obama White House applying the “climate test” to the permitting of energy infrastructure projects, has been met with mixed reaction by the fossil fuel industry and its legal counsel.

The Center for Liquefied Natural Gas, a pro-fracked gas exports group created by API, denounced the CEQ memo. So too did climate change denier U.S. Sen. James Inhofe (R-OK), as well as U.S. Rep. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY).

Industry attorneys, however, do not view the guidance with the same level of trepidation, at least not across the board. On one hand, the firms Holland & Knight and K&L Gates — both of which work with industry clients ranging from Chevron and ExxonMobil to Chesapeake Energy and Kinder Morgan — have pointed to the risk of litigation that could arise as a result of the NEPA guidance. On the other end of the spectrum, the firms Squire Patton Boggs and Greenberg Traurig LLP do not appear to be quite as alarmed.

Greenberg Traurig — whose clients include Duke Energy, BP, Arch Coal, and others — jovially pointed out in a memo thatCEQ‘s NEPA guidance does not take lifecycle supply chain greenhouse gas emissions into its accounting. The firm also points out that, with agency deference reigning supreme throughout the memo, “agencies should exercise judgment when considering whether to apply this guidance to the extent practicable to an on-going NEPA process.”

Francesca Ciliberti-Ayres, one of the Greenberg Traurig memo co-authors, formerly served as legal counsel for pipeline giant El Paso Corporation.

Similar to Greenberg Traurig, the firm Patton Boggs attempted to quell its clients’ fears in its own memo written in response to the CEQ guidance memo. Patton Boggs’ clients also have included a number of oil and gas energy companies and lobbying groups, such as API, ConocoPhillips, Halliburton, Marathon Oil, and others.

“The new guidance has the potential to add substantial time and expense to all environmental reviews for companies and other entities currently undergoing the NEPA process — and for future actions,” Patton Boggs’ attorneys wrote.

“However, it will likely take some time for agencies to acclimate their review processes to the new requirements. Interested persons and companies would help themselves both by developing internal off the shelf information to accommodate the new review requirements and by working with federal agencies to develop efficient methodologies to expedite consideration on this issue, minimize any additional review time and add clarity to the process.”

J. Gordon Arbuckle, a Patton Boggs memo co-author, has previously worked on permitting projects such as the massive Trans-Alaska Pipeline, the Alaska Natural Gas Pipeline, the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, and others.

Using NWP 12 to permit major pipeline projects in a quiet and less transparent manner made its debut in the Obama White House. However, it remains unclear whether its use, or the somewhat contradictory NEPA guidelines from CEQ, will ultimately shape Obama’s climate legacy in the years to come.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 17, 2016 | Mining & Drilling, NEWS

By Steve Horn / Desmog

TransCanada, owner of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline currently being contested in federal court and in front of a North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) legal panel, has won a $2.1 billion joint venture bid with Sempra Energy for a pipeline to shuttle gas obtained from hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale basin across the Gulf of Mexico and into Mexico.

The 500-mile long Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline, as reported on previously by DeSmog, is part of an extensive pipeline empire TransCanada is building from the U.S. to Mexico. The pipeline network is longer than the currently operating southern leg of the Keystone pipeline (now dubbed the Gulf Coast Pipeline). Unlike Keystone XL, though, these piecemeal pipeline section bid wins have garnered little media attention or scrutiny beyond the business and financial press.

The Sur de Texas-Tuxpan proposed pipeline route avoids the drug cartel violence-laden border city of Matamoros by halting at Brownsville and then going underwater across the U.S.-Mexico border to Tuxpan.

After it navigates the 500-mile long journey, Sur de Texas-Tuxpan will flood Mexico’s energy grid with gas under a 25-year service contract. That energy grid, thanks to the efforts of the U.S. State Department under then-Secretary of State and current Democratic Party presumptive presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, has been privatized under constitutional amendments passed in 2013.

TransCanada and Sempra were the only bidders. TransCanada owns the joint venture with Sempra — coined the Infraestructura Marina del Golfo, Spanish for “marine infrastructure of the Gulf” — on a 60-percent basis.

“We are extremely pleased to further our growth plans in Mexico with one of the most important natural gas infrastructure projects for that country’s future,” Russ Girling, TransCanada’s president and CEO, said in a press release announcing the bid win. “This new project brings our footprint of existing assets and projects in development in Mexico to more than US$5 billion, all underpinned by 25-year agreements with Mexico’s state power company.”

State Department Role, FERC and Presidential Permits for Sur de Texas-Tuxpan

David Leiter, a campaign finance bundler for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and former chief-of-staff for then-U.S.Senator and current Secretary of State John Kerry, lobbied the White House and the U.S. State Department in 2013 and 2014 on behalf of Sempra Energy on gas exports-related issues.

Sempra has a proposed liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal on the northwest, Baja California coast of Mexico calledEnergía Costa Azul (“Blue Coast Energy”) LNG. Leiter’s wife, Tamara Luzzatto, formerly served as chief-of-staff to then-U.S.Sen. Hillary Clinton.

Because the pipeline is set to carry natural gas, as opposed to oil, it does not need a U.S. State Department permit (though tacit and non-permitted unofficial approval could still prove important). Instead, it seemingly technically requires U.S.Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) approval, as well as a presidential permit.

It is unclear if Sur de Texas-Tuxpan will require a presidential permit, though, given the precedent set in the Wild Earth Nation, Et Al v. U.S. Department of State and Enbridge Energy case.

In that case, the Judge allowed Enbridge to break up its tar sands diluted bitumen (“dilbit”)-carrying Alberta Clipper (Line 67) pipeline into multiple pieces — helped along with off-the-books and therefore unofficial State Department authorization — avoiding the more onerous presidential and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) permit review process altogether.

Due to the legal precedent set in another related case, Delaware Riverkeeper v. FERC, oil and gas industry law firm Baker Botts explicitly recommended against utilizing the “segmentation” approach in a January 2015 memo that came out before the Enbridge case ruling.

“Project proponents should be careful to avoid potential ‘segmentation’ of a project into smaller parts simply to try to avoid a more thorough NEPA review,” wrote Baker Botts attorney Carlos Romo. “Segmentation occurs when closely related and interdependent projects are not adequately considered together in the NEPA process.”

The presidential candidates Clinton and Donald Trump have yet to comment on this pipeline or the topic of U.S.-Mexico cross-border pipelines on the campaign trail. But Financial Times, in an April article, pointed out that even Trump — who has pledged he will build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico — has little to say and will likely do little to halt cross-border lines like Sur de Texas-Tuxpan.

“As long as the wall doesn’t go below ground,” Mark Florian, head of the infrastructure fund at First Reserve and a former Goldman Sachs executive, told FT. “I think we’ll be OK.”

Though still fairly early on in the process, Florian’s words have proven true so far.

Photo by Helio Dilolwa on Unsplash