by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 11, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Toxification

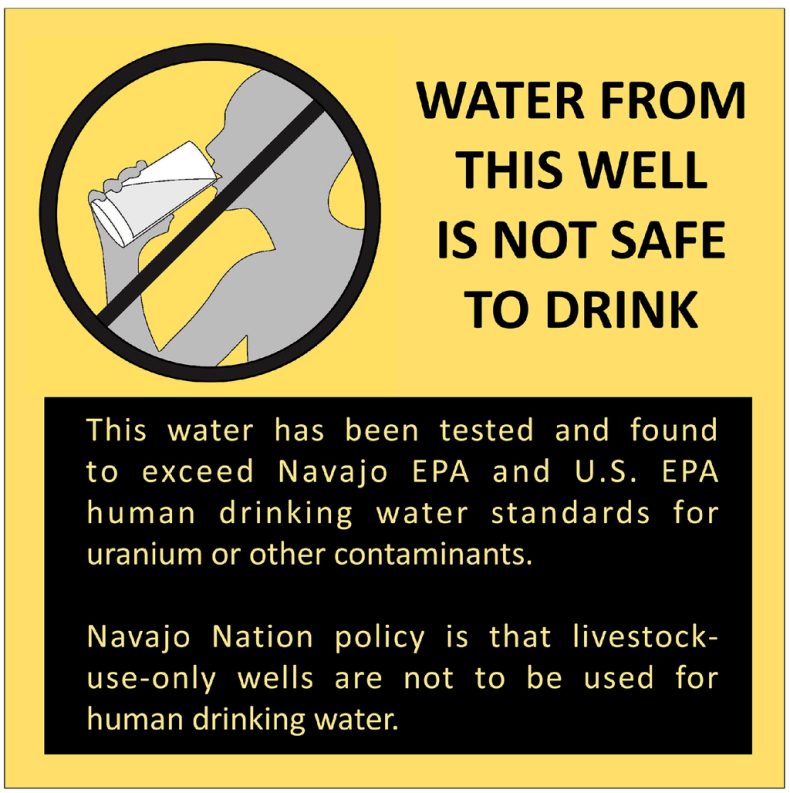

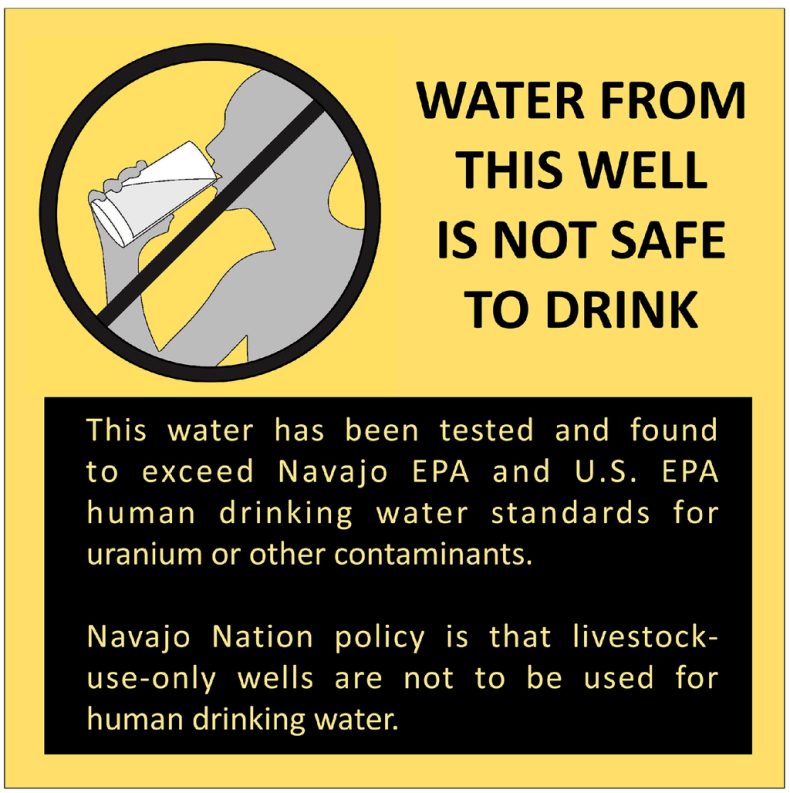

Featured image: Figure from EPA Pacific Southwest Region 9 Addressing Uranium Contamination on the Navajo Nation

By Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident. It is not. Rather, it is symptomatic of a much wider and deeper problem of environmental racism in the United States.

The history of uranium mining on Navajo (Diné) land is forever intertwined with the history of the military industrial complex. In 2002, the American Journal of Public Health ran an article entitled, “The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People.” Head investigators for the piece, Brugge and Gobel, framed the issue as a “tradeoff between national security and the environmental health of workers and communities.” The national history of mining for uranium ore originated in the late 1940’s when the United States decided that it was time to cut away its dependence on imported uranium. Over the next 40 years, some 4 million tons of uranium ore would be extracted from the Navajo’s territory, most of it fueling the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Situated by colonialist policies on the very margins of U.S. society, the Navajo didn’t have much choice but to seek work in the mines that started to appear following the discovery of uranium deposits on their territory. Over the years, more than 1300 uranium mines were established. When the Cold War came to an end, the mines were abandoned; but the Navajo’s struggle had just begun.

Back then, few Navajo spoke enough English to be informed about the inherent dangers of uranium exposure. The book Memories Come to Us in the Rain and the Wind: Oral Histories and Photographs of Navajo Uranium Miners and Their Families explains how the Navajo had no word for “radiation” and were cut off from more general public knowledge through language and educational barriers, and geography.

The Navajo began receiving federal health care during their confinement at Bosque Redondo in 1863. The Treaty of 1868 between the Navajos and the U.S. government was made in the good faith that the government – more specifically, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) – would take some responsibility in protecting the health of the Navajo nation. Instead, as noted in “White Man’s Medicine: The Navajo and Government Doctors, 1863-1955,” those pioneering the spirit of western medicine spent more time displacing traditional Navajo healers and knowledge banks, and much less time protecting Navajo public health. This obtuse, and ultimately short-sighted, attitude of disrespect towards Navajo healers began to shift in the late 1930’s; yet significant damage had already been done.

Founding director of the environmental cancer section of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Wilhelm C. Hueper, published a report in 1942 that tied radon gas exposure to higher incidence rates of lung cancer. He was careful to eliminate other occupational variables (like exposure to other toxins on the job) and potentially confounding, non-occupational variables (like smoking). After the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was made aware of his findings, Hueper was prohibited from speaking in public about his research; and he was reportedly even barred from traveling west of the Mississippi – lest he leak any information to at-risk populations like the Navajo.

In 1950, the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) began to study the relationship between the toxins from uranium mining and lung cancer; however, they failed to properly disseminate their findings to the Navajo population. They also failed to properly acquire informed consent from the Navajos involved in the studies, which would have required informing them of previously identified and/or suspected health risks associated with working in or living near the mines. In 1955, the federal responsibility and role in Navajo healthcare was transferred from the BIA to the USPHS.

In the 1960’s, as the incidence rates of lung cancer began to climb, Navajos began to organize. A group of Navajo widows gathered together to discuss the deaths of their miner husbands; this grew into a movement steeped in science and politics that eventually brought about the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) in 1999.

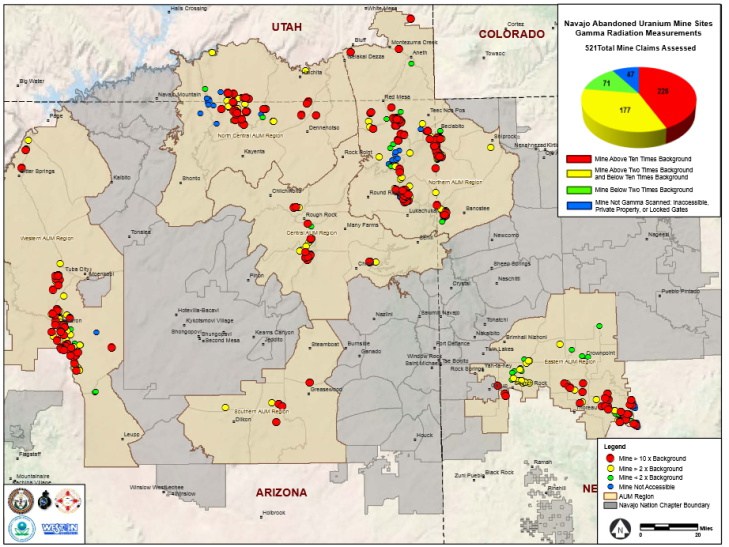

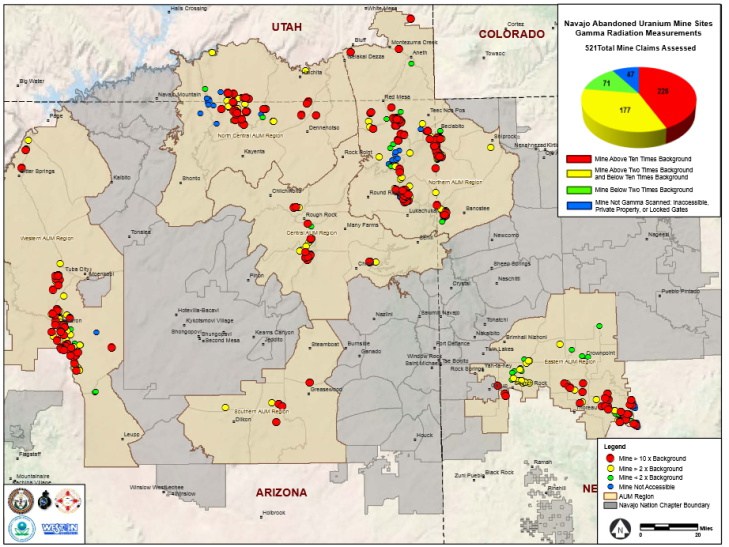

Cut to the present day. According to the US EPA, more than 500 of the existing 1300 abandoned uranium mines (AUM) on Navajo lands exhibit elevated levels of radiation.

Navajo abandoned uranium mines gamma radiation measurements and priority mines. US EPA

The Los Angeles Times gave us a sense of the risk in 1986. Thomas Payne, an environmental health officer from Indian Health Services, accompanied by a National Park Service ranger, took water samples from 48 sites in Navajo territory. The group of samples showed uranium levels in wells as high as 139 picocuries per liter. Levels In abandoned pits were far more dangerous, sometimes exceeding 4,000 picocuries. The EPA limit for safe drinking water is 20 picocuries per liter.

This unresolved plague of radiation is compounded by pollution from coal mines and a coal-fired power plant that manifests at an even more systemic level; the entire Navajo water supply is currently tainted with industry toxins.

Recent media coverage and spiraling public outrage over the water crisis in Flint, Michigan has completely eclipsed the ongoing environmental justice struggles of the Navajo. Even worse, the media continues to frame the situation in Flint as some sort of isolated incident.

Madeline Stano, attorney for the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, assessed the situation for the San Diego Free Press, commenting, “Unfortunately, Flint’s water scandal is a symptom of a much larger disease. It’s far from an isolated incidence, in the history of Michigan itself and in the country writ large.”

Other instances of criminally negligent environmental pollution in the United States include the 50-year legacy of PCB contamination at the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation (HNR) situated in the Yakama Nation’s “front yard.”

While many environmental movements are fighting to establish proper regulation of pollutants at state, federal, and even international levels, these four cases are representative of a pervasive, environmental racism that stacks up against communities like the Navajo and prevents them from receiving equal protection under existing regulations and policies.

Despite the common thread among these cases, the wave of righteous indignation over the ongoing tragedy in Flint has yet to reach the Navajo Nation, the Mohawk community of Akwesasne, the Yakama Nation – or the many other Indigenous communities across the United States that continue to endure various toxic legacies in relative silence.

Current public outcry may be a harbinger, however, of an environmental justice movement ready to galvanize itself towards a higher calling, one that includes all peoples across the United States, and truly shares the ongoing, collective environmental victories with all communities of color.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2016 | Building Alternatives, Repression at Home, Toxification

Originally published in the September/October 2012 issue of Orion. Now republished for the first time online.

In an era of government-sanctioned polluters, communities must defend themselves

Several years ago I spoke at a benefit for an organization working to prevent a toxic waste site from being built in their community. Yet another toxic waste site, the organizers clarified, since there already was one. It should surprise no one that their community was primarily poor, primarily people of color, and that the toxic waste was being brought in so that distant corporations could reap bigger profits.

The organization had been fighting the dump for years, on every level, from filing lawsuits to holding protests to physically blockading the dump site. Several people at the benefit commented on the bizarre role that the police played in all of this. Many of the cops lived in the community and were themselves opposed to the toxic dump. But when they put on their uniforms and headed off to work, their jobs included arresting their neighbors who were trying to protect the neighborhoods where their own children lived and played.

We’ve all heard of dues-paying union cops busting the heads of strikers because their capitalist bosses tell them to. And of cops arresting protesters trying to prevent the cops’ own water supplies from being toxified (while of course not arresting the capitalists who are toxifying the water supplies). And I’m sure I’m not the only one who’s had fantasies that at the next economic summit or World Bank meeting, members of the police will experience an epiphany of conscience and realize they share class interests not with those they’re protecting but rather with those at whom they’re pointing their guns. And in this fantasy the police then turn as one to join the protesters and face their real enemy.

At the benefit we shared all sorts of fantasies like these, and we all laughed at how unrealistic they were. There have been instances in which the police have worked with the people to stop government or corporate atrocities, but they’re too rare.

And then we shared some other fantasies, which all consisted in one way or another of police choosing to enforce laws that are already on the books, laws that protect our communities. Laws like the Clean Air Act, or the Clean Water Act, or for that matter laws against rape. We fantasized about what it might be like to have police enforce carcinogen-free zones, or dam-free zones, or WalMart-free zones, or rape-free zones.

And then again we laughed, since we knew that these fantasies, too, were unrealistic. It’s not the job of the police to protect you from living in a toxified landscape, even if that landscape is being toxified illegally.

In fact — and this may or may not be surprising to you — the police are under no legal obligation to protect you at all. This fact has been upheld in courts again and again. In one case, two women in Washington DC were upstairs in their townhouse when they heard their roommate being assaulted downstairs. Several times they phoned 911 and each time were told police were on their way. A half hour later their roommate stopped screaming, and, assuming the police had arrived, they went downstairs. But the police hadn’t arrived, and so for the next fourteen hours all three women were repeatedly beaten and raped. The women sued the District of Columbia and the police for failing to protect them, but the district’s highest court ruled against them, saying that it is “a fundamental principle of American law that a government and its agents are under no general duty to provide public services, such as police protection, to any individual citizen.”

So there you have it. Time and again, many similar cases have yielded the same case law, at local, state, and federal levels. But a lot of rape victims already know this; only 6 percent of rapists spend even one night in jail. And the people in that community who were having a toxic waste dump crammed down their throats with the professional support of the police also know this. As do the human and nonhuman people of the Gulf of Mexico, who are still being killed or injured by the Deepwater catastrophe — and who will experience far more of the same, since the U.S. government is supporting more deepwater drilling. As one technical advisor to the oil and gas industry put it, “We are seeing deep-water drilling coming back with a vengeance in the Gulf.”

So here’s the question: if the police are not legally obligated to protect us and our communities — or if the police are failing to do so, or if it is not even their job to do so — then if we and our communities are to be protected, who, precisely is going to do it? To whom does that responsibility fall? I think we all know the answer to that one.

A lot of people seem to love to talk about the virtues of self- and community-reliance, but where are they when we need to defend our communities?

Fortunately there are many examples of communities rising up to defend themselves from wrongdoing from which we can and should learn. Pre-Revolutionary — or you could say revolutionary yet pre-1776 — American patriots, sick and tired of rule by a distant elite (sound familiar?), increasingly refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Crown Courts and other institutions, and put in place their own systems of justice. The same has been true for the Irish in their struggle for independence. The same was true of the Spanish anarchists: part of their project included pushing fascists out of their communities and another part consisted of putting in place their own neighborhood systems of justice and community protection.

I think often of something a former head of “security” for South Africa under apartheid said: that what they’d been most afraid of from the revolutionary group the African National Congress had never been the ANC’s sabotage or even their violence, but rather that the ANC might be able to convince the mass of South Africans to not believe in law and order as such, which in this case meant the law and order imposed by the apartheid regime, which in this case meant the legitimacy of the exploitative apartheid government, which in this case meant that their greatest fear was that the ANC would convince the majority of people to withdraw their consent to be governed by an elite that does not have their best interests at heart.

In our case, we don’t need an ANC to convince us of the illegitimacy of many of the actions of those in power. Those in power are doing a great job of convincing us by their own actions. If the Gulf catastrophe (and the continuation of deepwater drilling) doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If fracking and the poisoning of our groundwater doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the governmental response to global warming — ranging from vindictiveness against climate scientists to denial to measures that at very best are completely incommensurate with the threat — doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. If the total toxification of the environment, with its inevitable health consequences for both humans and nonhumans, doesn’t convince you, I don’t know what will. I routinely ask the people at my talks whether they have had someone they love die of cancer, and at least 75 percent almost always say yes.

And when I ask people at my talks if they believe that state and federal governments take better care of corporations or of human beings, no one — and I mean no one — ever says human beings. Reframing the question to consider whether governments take better care of corporations or the planet — our only home — yields the same result.

If police are the servants of governments, and if governments protect corporations better than they do human beings (and far better than they do the planet), then clearly it falls to us to protect our communities and the landbases on which we in our communities personally and collectively depend. What would it look like if we created our own community groups and systems of justice to stop the murder of our landbases and the total toxification of our environment? It would look a little bit like precisely the sort of revolution we need if we are to survive. It would look like our only hope.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Dec 26, 2015 | Lobbying, Toxification

Featured Image: Alali Efanga & Chief Fidelis Oguru from Oruma, two plaintiffs in the Dutch court case against Shell. (Photo: Milieudefensie/flickr)

In a potentially precedent-setting ruling, a Dutch court said Friday that Royal Dutch Shell may be held liable for oil spills at its subsidiary in Nigeria—a win for farmers and environmentalists attempting to hold the oil giant accountable for leaks, spills, and widespread pollution.

The ruling by the Court of Appeals in the Hague, which overturns a 2013 decision in favor of Shell, allows four Nigerian farmers to jointly sue the fossil fuels corporation in the Netherlands for causing extensive oil spills in Nigeria.

The scars of those disasters are still visible in the fields and fishing ponds of three Nigerian villages. In one village, drinking water has been rendered non-potable, while in another, an entire mangrove forest has been destroyed.

Alali Efanga, one of the Nigerian farmers who, along with Friends of the Earth Netherlands, brought the case against Shell, said the ruling “offers hope that Shell will finally begin to restore the soil around my village so that I will once again be able to take up farming and fishing on my own land.”

Beyond that, the court’s decision “is a landslide victory for environmentalists and these four brave Nigerian farmers who, for more than seven years, have had the courage to take on one of the most powerful companies in the world,” said Geert Ritsema, campaigner at Friends of the Earth Netherlands. “This ruling is a ray of hope for other victims of environmental degradation, human rights violations, and other misconduct by large corporations.”

Indeed, as Amnesty International researcher Mark Dummett said in advance of the ruling: “This case is especially important as it could pave the way for further cases from other communities devastated by Shell’s negligence.”

“There have been thousands of spills from Shell’s pipelines since the company started pumping oil in the Niger Delta in 1958,” Dummett said, “with devastating consequences for the people living there.”

Decrying the “incredible levels of pollution” caused by the activities of Shell and its subsidiaries, environmentalists Vandana Shiva and Nnimmo Bassey said at a media briefing in July that “weekends in Ogoniland are marked by carnivals of funerals of people in their 20s and 30s.”

Citing a 2011 United Nations Environmental Programme assessment, they noted that in over 40 locations tested in Ogoniland, the soil is polluted with hydrocarbons up to a depth of 5 meters and that all the water bodies in the region are polluted.

The UN report, they said, also found that in some places the water was polluted with benzene, a known carcinogen, at levels 900 above World Health Organization standards. “With life expectancy standing at about 41 years, the clean up of Ogoniland is projected to require a cumulative 30 years to clean both the land and water,” they said.

In another historic victory for the plaintiffs, the Hague court on Friday also ordered Shell to give the farmers and environmental activists supporting their case access to internal documents that the court said could shed more light on the case.

Channa Samkalden, counsel for the farmers and Friends of the Earth, said it was “the first time in legal history that access to internal company documents was obtained in court…This finally allows the case to be considered on its merits.”

The court will continue to hear the case in March 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 License

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 11, 2015 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Mining & Drilling, Toxification

Elvira Nascimento

Cyntia Beltrão reports from Brazil on what may be the country’s worst environmental disaster ever, at the Samarco open pit project jointly owned by Vale and BHP Billiton:

Last Thursday, November 5th, two dams containing mine tailings and waste from iron ore mining burst, burying the small historic town of Bento Rodrigues, district of Mariana, Minas Gerais state. The village, founded by miners, used to gain its sustenance from family farming and from labor at cooperatives. For many years, the people successfully resisted efforts to expel them by the all-powerful mining company Vale (NYSE: VALE, formerly Vale do Rio Doce, after the same river now affected by the disaster). Now their land is covered in mud, with the full scale of the death toll and environmental impacts still unknown.

Officially there are almost thirty dead, including small children, with several still missing. The press and the government hide the true numbers. Independent journalists say that the number of victims is much larger.

The environmental damage is devastating. The mud formed by iron ore and silica slurry spread over 410 miles. It reached one of the largest Brazilian rivers, the Rio Doce (“Sweet River”), at the center of our fifth largest watershed. The Doce River already suffers from pollution, silting of margins, cattle grazing in the basin land, and several eucalyptus plantations that drain the land. This year Southeastern Brazil, a region with a normally mild climate, endured a devastating drought. Authorities imposed water rationing on several major cities. Meanwhile, miners contaminate ground water and exploit lands rich in springs. The Doce River, once great and powerful, is now almost dry, even in its estuary. The mud of mining waste further injures the life of the river.

We do not know if the mud is contaminated by mercury and arsenic. Samarco / Vale says it isn’t, but we know that its components, iron ore and silica, will form a cement in the already dying river. This “cement” will change the riverbed permanently, covering the natural bed and artificially leveling its structure. The mud is sterile, and nothing will grow where it was deposited. A fish kill is already occuring. We do not know the full extent of impacts on river life or for those who depend on the river’s waters.

Soon the dirty mud will reach the sea, where it will cause further damage, to the important Rio Doce estuary and to the ocean.

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

Some resources in Portuguese to learn more and get active:

by DGR Editor | Sep 7, 2015 | Toxification

By Kim Hill / Deep Green Resistance Australia

I think I’m dying. My heart is beating too fast, I’m too weak to get out of bed most days, and some days I don’t even have the energy to eat. It’s been like this for years. It’s been getting gradually worse.

I haven’t read a book, taken a walk, watched a movie, visited a friend, or done anything useful in months. I can’t focus, can’t even think most of the time.

I’m not the only one. Many of my friends are also ill. I see the sickness all around me. Every year there are less fish in the sea, less birds in the trees, less insects. The air smells more toxic, the industrial noise is getting louder. Every day, 200 species become extinct. Most rivers no longer support any life. Around half of all human deaths are caused by pollution. We’re all dying of the sickness.

My own illness can be attributed to heavy metal and chemical toxicity, from mining, vaccines, vehicle exhaust, and all the chemicals I’m exposed to every day, indoors and out. They’re in my food, in the air, in the water I drink. I can’t get away from them. There’s no safe place left to go. I can’t get any better while these are still being made, being used, being disposed of into my body.

It’s not just chemicals, but electromagnetic fields, from powerlines, phones, wifi and cell phone towers. The food of industrial agriculture, grown in soils depleted of nutrients and becoming ever more poisoned, is all I can get. It barely provides me with the nutrients I need to survive, let alone recover. Let food be thy medicine, but when the food itself spreads the sickness, there’s not much hope for anyone.

When the soil life dies, the entire landscape becomes sick. The trees can’t provide for their inhabitants. They can’t hold the community of life together. The intricate food web, the web of relationships that holds us all, collapses.

Will I recover? With the constant assault of chemicals, electromagnetic fields, and noise, it seems unlikely. Will the living world recover, or will it die along with me, unable to withstand the violent industries that extract the lifeblood of rivers, forests, fish and earth, to convert them into a quick profit?

Western medicine can’t help me. All it can offer is more chemicals, more poisons. And new technology can’t help the land, the water, the soil. It only worsens the sickness.

If I am to heal, the living world must first be healed. The water, the food, the air and the land need to recover from the sickness, as they are the only medicine that can bring me back to health.

The machines need to be stopped. The mining, ploughing, fishing, felling, and manufacturing machines. The advertising, brainwashing and surveillance machines. The coal, oil, gas, nuclear and solar-powered machines. They are all spreading the sickness. It’s a cultural sickness, as well as a physical one. Our culture is so sick that it barely acknowledges the living world, and has us believe that images, ideas, identities and abstractions are all we need. It all needs to stop. The culture needs to recover, to repair.

I need your help. I can’t do this myself. I’m close to death. To those who are not yet sick, those who have the strength to stand with the living, and stop the sickness: I need you now. Not just for me, but for everyone. For those close to extinction, those who still have some chance of recovery. We all need you.

Today is the last day on Earth for many species of plants and animals. Every day, the sickness consumes a few more of us. If I didn’t have friends and family looking after me, I wouldn’t be alive today. When the whole community becomes sick, there is no-one left to take care. This is how extinction happens.

It doesn’t have to happen. It can be stopped. Some people, mostly those in the worst affected areas, are taking on the sickness, fighting because they know their lives depend on it. They see the root cause of the affliction, not just the symptoms. They are taking down oil rigs, derailing coal trains, and sabotaging pipelines and mining equipment. They’re blockading ports, forests, mine sites and power stations, and doing everything they can to stop the sickness spreading further. They are few, and they get little thanks. They need all the help they can get. With a collective effort, the sickness can be eradicated, and we can all recover our health.

From Stories of Creative Ecology August 28, 2015

by DGR News Service | Oct 7, 2014 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Colonialism & Conquest, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Toxification

By Sacred Mauna Kea

Mauna Kea Protest

Tuesday, October 7, 2014 — 7am to 2pm,

Saddle Road at the entrance to the Mauna Kea Observatory Road

Native Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians will gather for a peaceful protest against the Astronomy industry and the “State of Hawaii’s” ground- breaking ceremony for a thirty-meter telescope (TMT) on the summit of Mauna Kea.

Native Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians will gather for a peaceful protest

against the Astronomy industry and the “State of Hawaii’s” ground-

breaking ceremony for a thirty-meter telescope (TMT) on the summit of

Mauna Kea.

CULTURAL ISSUES: Mauna Kea is sacred to the Hawaiian people, who

maintain a deep connection and spiritual tradition there that goes

back millennia.

“The TMT is an atrocity the size of Aloha Stadium,” said Kamahana

Kealoha, a Hawaiian cultural practitioner. “It’s 19 stories tall,

which is like building a sky-scraper on top of the mountain, a place

that is being violated in many ways culturally, environmentally and

spiritually.” Speaking as an organizer of those gathering to protest,

Kealoha said, “We are in solidarity with individuals fighting against

this project in U.S. courts, and those taking our struggle for

de-occupation to the international courts. Others of us must protest

this ground-breaking ceremony and intervene in hopes of stopping a

desecration.”

Clarence “Ku” Ching, longtime activist, cultural practitioner, and a

member of the Mauna Kea Hui, a group of Hawaiians bringing legal

challenges to the TMT project in state court, said, “We will be

gathering at Pu’u Huluhulu, at the bottom of the Mauna Kea Access

Road, and we will be doing prayers and ceremony for the mountain.”

When asked if he will participate in protests, he said, “We’re on the

same side as those who will protest, but my commitment to Mauna Kea is

in this way. We are a diverse people…everyone has to do what they know

is pono.”

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES: The principle fresh water aquifer for Hawaii

Island is on Mauna Kea, yet there have been mercury spills on the

summit; toxins such as Ethylene Glycol and Diesel are used there;

chemicals used to clean telescope mirrors drain into the septic

system, along with half a million gallons a year of human sewage that

goes into septic tanks, cesspools and leach fields.

“All of this poisonous activity at the source of our fresh water

aquifer is unconscionable, and it threatens the life of the island,”

said Kealoha. “But that’s only part of the story of this mountain’s

environmental fragility. It’s also home to endangered species, such as

the palila bird, which is endangered in part because of the damage to

its critical habitat, which includes the mamane tree.”

LEGAL ISSUES: Mauna Kea is designated as part of the Crown and

Government lands of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Professor Williamson PC Chang, from the University of Hawaii’s

Richardson School of Law, said, “The United States bases its claim to

the Crown and Government land of the Hawaiian Kingdom on the 1898

Joint Resolution of Congress, but that resolution has no power to

convey the lands of Hawaii to the U.S. It’s as if I wrote a deed

saying you give your house to me and I accepted it. Nobody gave the

land to the U.S., they just seized it.”

“Show us the title,” said Kealoha. “If the so-called ‘Treaty of

Annexation’ exists, that would be proof that Hawaiian Kingdom citizens

gave up sovereignty and agreed to be part of the United States 121

years ago. But we know that no such document exists. The so-called

‘state’ does not have jurisdiction over Mauna Kea or any other land in

Hawaii that it illegally leases out to multi-national interests.”

“I agree with how George Helm felt about Kahoolawe,” said Kealoha. “He

wrote in his journal: ‘My veins are carrying the blood of a people who

understood the sacredness of land and water. Their culture is my

culture. No matter how remote the past is it does not make my culture

extinct. Now I cannot continue to see the arrogance of the white man

who maintains his science and rationality at the expense of my

cultural instincts. They will not prostitute my soul.’”

“We are calling on everyone, Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians alike, to

stand with us, to protect Mauna Kea the way George and others

protected Kahoolawe. I ask myself every day, what would George Helm

do? Because we need to find the courage he had and stop the

destruction of Mauna Kea.”

From Sacred Mauna Kea: http://sacredmaunakea.wordpress.com/