By GERRY MCGOVERN, SUE BRANFORD / Mongabay

In 2022, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres declared that the “lifeline of renewable energy can steer [the] world out of climate crisis.” In saying so, he echoed a popular and tantalizing idea: that, if we hurry, we can erase the climate emergency with widespread adoption of renewables in the form of solar panels, wind farms, electric vehicles and more.

But things aren’t that simple, and analysts increasingly question the naïve assumption that renewables are a silver bullet.

That’s partly because the rapid transition to a global energy and transport system powered by “clean” energy brings with it a host of new (and old) environmental problems. To begin with, stepping up solar, wind and EV production requires many more minerals and materials in the short term than do their already well-established fossil fuel counterparts, while also creating a major carbon footprint.

Also, the quicker we transition away from fossil fuel tech to renewable tech, the greater the quantity of materials needed up front, and the higher the immediate carbon and numerous other environmental costs. But this shift is now happening extremely rapidly, as companies, governments and consumers try to turn away from oil, coal and natural gas.

“Renewables are moving faster than national governments can set targets,” declared International Energy Agency executive director Fatih Birol. In its “ Renewables 2024” report, the IEA estimates the world will add more than 5,500 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity between 2024 and 2030 — almost three times the increase between 2017 and 2023.

But this triumph hasn’t brought with it a simultaneous slashing in global emissions, as hoped. In fact, 2023 saw humanity’s biggest annual carbon releases ever, totaling 37.4 billion metric tons, which has led experts to ask: What’s going on?

Jevons paradox meets limits to growth

Some analysts suggest the source of this baffling contradiction regarding record modern energy consumption can be found in the clamor by businesses and consumers for more, better, cheaper technological innovations, an idea summed up by a 160-year-old economic theory: the Jevons paradox.

Postulated by 19th-century English economist William Stanley Jevons, it states that, “in the long term, an increase in efficiency in resource use [via a new technology] will generate an increase in resource consumption rather than a decrease.” Put simply, the more efficient (and hence cheaper) energy is, the greater society’s overall production and economic growth will be — with that increased production then requiring still more energy consumption.

Writing in 1865, Jevons argued that the energy transition from horses to coal decreased the amount of work for any given task (along with the cost), which led to soaring resource consumption. For proof, he pointed to the coal-powered explosion in technological innovation and use occurring in the 19th century.

Applied to our current predicament, the Jevons paradox challenges and undermines tech prognosticators’ rosy forecasts for sustainable development.

Here’s a look at the paradox in action: The fastest-expanding renewable energy sector today is solar photovoltaics (PVs), expected to account for 80% of renewables growth in the coming years.

In many parts of the world, large solar power plants are being built, while companies and households rapidly add rooftop solar panels. At the head of the pack is China, with its astounding solar installation rate ( 216.9 GW in 2023).

But paradoxically, as China cranks out cheap solar panels for domestic use and export, it is also building six times more coal power plants every year than the rest of the world combined, though it still expects almost half its electricity generation to come from renewables, mainly solar, by 2028.

This astronomical growth at first seems like proof of the Jevons paradox at work, but there’s an unexpected twist: Why is China (and much of the rest of the world) still voraciously consuming outmoded, less-efficient fossil fuel tech, while also gobbling up renewables?

One reason is that coal and oil are seen as reliable, not subject to the same problems that renewables can face during periods of intense drought or violent weather — problems caused by the very climate change that renewables are intended to mitigate.

Another major reason is that fossil fuels continue being relatively cheap. That’s because they’re supported by vast government subsidies ( totaling more than $1 trillion annually. So in a sense, we are experiencing a quadruple Jevons paradox, with oil, coal, natural gas and renewables acting like four cost-efficient horses, all racing to produce more cheap stuff for an exploding world consumer economy. But this growth comes with terrible environmental and social harm.

Exponential growth with a horrific cost

Back to the solar example: China is selling its cheap solar installations all over the globe, and by 2030 could be responsible for half the new capacity of renewables installed planetwide. But the environmental cost of satisfying that escalating demand is rippling out across the world.

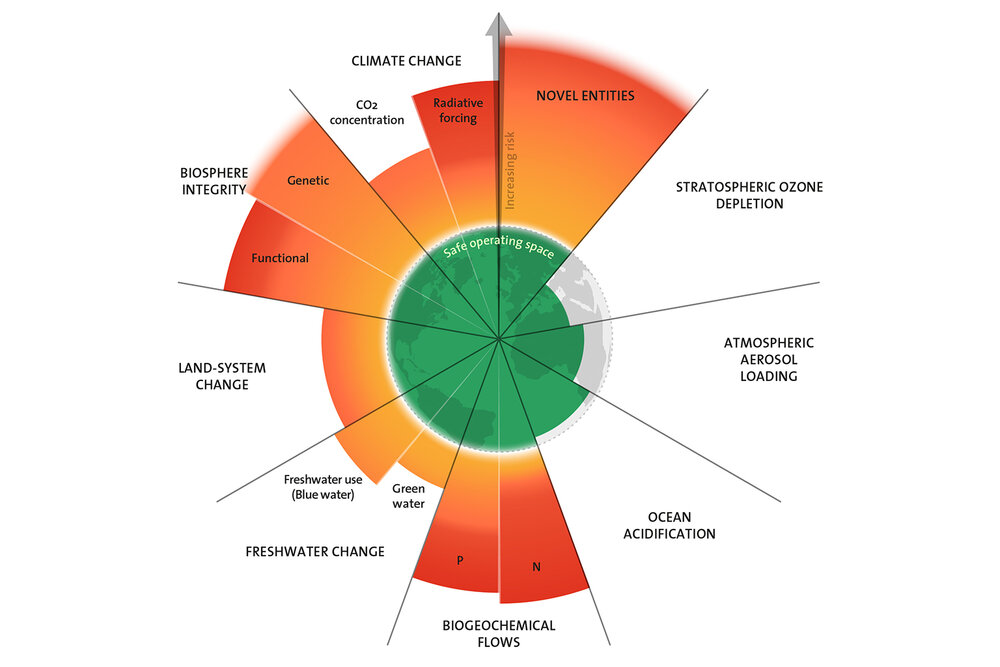

It has spurred a huge mining boom. Desperate to satisfy fast-rising demand, companies and nations are mining in ever more inaccessible areas, which costs more in dollars, carbon emissions, biodiversity losses, land-use change, freshwater use, ocean acidification, plus land, water and air pollution. So, just as with fossil fuels, the rush to renewables contributes to the destabilizing of the [nine planetary boundaries](https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/trillion-dollar-question-fossil-fuel-subsidies-2024-11-15/#:~:text=The%20International%20Energy%20Agency%20(IEA,at%20%24620%20billion%20in%202023.), of which six are already in the red zone, threatening civilization, humanity and life as we know it.

Mining, it must be remembered, is also still heavily dependent on fossil fuels, so it generates large quantities of greenhouse gases as it provides minerals for the renewables revolution. A January 2023 article in the MIT Technology Review predicts that the mining alone needed to support renewables will produce 29 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions between now and 2050.

Carbon is far from the only problem. Renewables also require a wide range of often difficult-to-get-at minerals, including nickel, graphite, copper, rare earths, lithium and cobalt. This means “paradoxically, extracting this large amount of raw materials [for renewables] will require the development of new mines with a larger overall environmental footprint,” says the MIT article.

There are other problems too. Every year 14,000 football fields of forests are cut down in Myanmar to create cheap charcoal for China’s smelting industries to process silicon, a key component of solar panels and of computers.

This rapid development in rural places also comes with harsh human costs: Mongabay has reported extensively on how Indigenous people, traditional communities and fragile but biodiverse ecosystems are paying the price for the world’s mineral demand in the transition to renewable energy.

There is strong evidence that the Uighur minority is being used as slave labor to build solar panels in China. There are also reports that workers are dying in Chinese factories in Indonesia that are producing nickel, a key metal for solar panels and batteries.

The search for solutions

“We really need to come up with solutions that get us the material that we need sustainably, and time is very short,” said Demetrios Papathanasiou, global director for energy and extractives at the World Bank.

One popularly touted solution argues that the impacts imposed by the rapid move to renewable energy can be greatly reduced with enhanced recycling. That argument goes this way: The minerals needed to make solar panels and build windfarms and electric vehicles only need to be sourced once. Unlike fossil fuels, renewables produce energy year after year. And the original materials used to make them can be recycled again and again.

But there are problems with this position.

First, while EV batteries, for example, may be relatively long lasting, they only provide the energy for new electric vehicles that still require steel, plastics, tires and much more to put people in the Global North and increasingly the Global South on the road. Those cars will wear out, with tires, electronics, plastics and batteries costly to recycle.

The solar energy industry says that “solar panels have an expected lifespan between 25-30 years,” and often much longer. But just because a product can last longer, does that mean people won’t clamor for newer, better ones?

In developed nations, for example, the speed at which technology is evolving mitigates against the use of panels for their full lifespan. A 2021 article in the Harvard Business Review found that, after 10 years or even sooner, consumers will likely dispose of their first solar panels, to install newer, more efficient ones. Again, the Jevons paradox rears its anti-utopian head.

Also, as solar proliferates in poorer nations, so too will the devices that solar can drive. As solar expands in the developing world, sales for cheap solar lanterns and small solar home electric systems are also expanding. An article in the journal Nature Energy calculates that in 2019 alone, more than 35 million solar products were sold, a huge rise from the 200,000 such products sold in 2010.

This expansion brings huge social benefits, as it means rural families can use their smartphones to study online at night, watch television, and access the market prices of their crops — all things people in the Global North take for granted.

But, as the article points out, many developing-world solar installations are poor quality and only last a few years: “Many, perhaps even the majority, of solar products sold in the Global South … only have working lives of a couple of years.” The problem is particularly acute in Africa. “Think of those solar panels that charge phones; a lot of them do not work, so people throw them away,” said Natalie Gwatirisa, founder of All For Climate Action, a Zimbabwean youth-led organization that strives to raise awareness on climate change. Gwatirisa calculates that, of the estimated 150 million solar products that have reached Africa since 2010, almost 75% have stopped working.

And as Americans familiar with designed obsolescence know, people will want replacements: That means more solar panels, cellphones, computers, TVs, and much more e-waste.

Another disturbing side to the solar boom is the unbridled growth of e-waste, much of it toxic. Gwatirisa cautions: “Africa should not just open its hand and receive [anything] from China because this is definitely going to lead to another landfill in Africa.”

The developed world also faces an e-waste glut. Solar panels require specialized labor to recycle and there is little financial incentive to do so. While panels contain small amounts of valuable minerals such as silver, they’re mostly made of glass, an extremely low-value material. While it costs $20-$30 to recycle a panel, it only costs $1-$2 to bury it in a landfill. And the PV industry itself admits that ’the solar industry cannot claim to be a “clean” energy source if it leaves a trail of hazardous waste.’

renewables

Solving the wrong problem

Ultimately, say some analysts, we may be trying to solve the wrong problem. Humanity is not experiencing an energy production problem, they say. Instead, we have an energy consumption problem. Thus, the key to reducing environmental harm is to radically reduce energy demand. But that can likely only be done through stationary — or, better still, decreased — consumption.

However, it’s hard to imagine modern consumers not rushing out to buy the next generation of consumer electronics including even smarter smartphones, which demand more and more energy and materials to operate (think global internet data centers). And it’s also hard to imagine industry not rushing to update its ever more innovative electronic product lines (think AI).

A decline in energy demand is far from happening. The U.S. government says it expects global energy consumption to increase by almost 50% by 2050, as compared with 2020. And much of that energy will be used to make new stuff, all of which increases resource demand and increases our likelihood of further overshooting already overshot planetary boundaries and crashing overstressed Earth systems.

One essential step toward sustainability is the circular economy, say renewable energy advocates. But, as with so much else, every year we somehow go in the opposite direction. Our current economic system is becoming more and more linear, built on a model of extracting more raw materials from nature, turning them into more innovative products, and then discarding it all as waste.

Currently, only 7.2% of used materials are cycled back into our economies after use. This puts an overwhelming burden on the environment and contributes to the climate, biodiversity and pollution crises.

If a circular economy could be developed by recycling all the materials used in renewables, it would significantly reduce the constant need to mine and source new ones. But, while efficient recycling will undoubtedly help, it also has limitations.

renewables

The future

Tom Murphy, a professor emeritus of the departments of physics and astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, San Diego, became so concerned about the world’s future, he shifted his career focus to energy.

While initially a big promoter of renewables, having built his own solar panels back in 2008, he has recently turned skeptical. Panels “need constant replacement every two or three decades ad infinitum,” he told Mongabay. “Recycling is not a magic wand. It doesn’t pull you out of the need for mining. This is because recycling is not 100% efficient and never will be. In the laboratory maybe, but not in the real world. You’re going to have this continual bleed of materials out of the system.”

Yet another renewables problem is that sustainable energy is often siloed: It is nearly always talked about only in the context of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Rarely are the total long-term supply chain costs to the environment and society calculated.

Reducing CO2 is clearly a vital goal, but not the only critical one, says Earth system scientist Johan Rockström, joint director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, and who (with an international team of scientists), developed the planetary boundaries framework.

It is undeniably important to reduce greenhouse emissions by half over the next seven years in order to reach net zero by 2050, he says. But this will be difficult to achieve, for it means “cutting emissions by 7.5% a year, which is an exponential decline.”

And even if we achieve such radical reductions, it will not solve the environmental crisis, warns Rockström. That’s because radical emission reductions only tackle the climate change boundary. A recent scientific paper, to which he contributed, warns that “six of the nine boundaries are transgressed, suggesting that Earth is now well outside of the safe operating space for humanity.”

Rockström in an exclusive interview told Mongabay that, at the same time as we vigorously combat global warming, “We also need to come back into the safe space for pollutants, nitrogen, phosphorus, land, biodiversity,” and more. This means that our efforts to repair the climate must also relieve stresses on these other boundaries, not destabilize them further.

Murphy says he believes this can’t be achieved. He says that modernity — the term he uses to delineate the period of human domination of the biosphere — cannot be made compatible with the protection of the biological world.

To make his point, he emphasizes an obvious flaw in renewables: they are not renewable. “I can’t see how we can [protect the biosphere] and retain a flow of nonrenewable finite resources, which is what our economic system requires.” He continues: “We are many orders of magnitude, 4 or 5 orders of magnitude, away from being at a sustainable scale. I like Rockström’s idea that we have boundaries, but I think his assessment of how far we have exceeded those boundaries is completely wrong.”

Murphy says he believes modernity has unleashed a sixth mass extinction, and it is too late to stop it. Modernity, he says, was unsustainable from the beginning: “Our brains can’t conceive of the degree of interconnectedness in the living world we’re part of. So the activities we started carrying out, even agriculture, don’t have a sustainable foundation. The minerals and materials we use are foreign to the living world and we dig them up and spew them out. They end up all over the place, even in our bodies at this point, [we now have] microplastics. This is hurting not just us, but the whole living world on which we depend.”

Like Murphy, Rockström says he is pessimistic about the level of action now seen globally, but he doesn’t think we should give up. “We have the responsibility to continue even if we have a headwind.” What is extremely frustrating, he says, is that today we have the answers: “We know what we need to do. That’s quite remarkable. Years back I could not have said that. We have solutions to scale down our use of coal, oil and gas. We know how to feed humanity from sustainable food systems, that largely bring us back into the [safe zone for] planetary boundaries, the safe space for nitrogen, phosphorous, freshwater, land and biodiversity.”

One key to making such radical change would be a dramatic, drastic, wholesale shift by governments away from offering trillions of dollars in “ perverse subsidies” to environment-destroying fossil fuel and mining technologies, to pumping those subsidies into renewables and the circular economy.

Murphy says he doesn’t believe we should give up either. But he also says he doesn’t believe modernity can be made sustainable. “I suspect that the deteriorating web of life will create cascading failures that end up pulling the power cord to the destructive machine. Only then will some people accept that ecological ignorance — paired with technological capability — has dire consequences.”

But, he adds, this does not mean the human race is doomed.

“The modernity project does not define humanity. Humanity is much older. It’s too late for modernity to succeed but it’s not too late for humanity to succeed.” Here he turns to Indigenous cultures: “For hundreds of thousands of years, they survived and did quite well without causing the sixth mass extinction.”

“There isn’t a single Indigenous package,” he says. “Each is tuned to its [particular local] environment, and they vary a lot. But they have common elements: humility, only taking what you need from the environment, and the belief that we can learn a lot from our ‘our brothers and sisters,’ that is, the other animals and plants who have been around for much longer than us.”

Perhaps surprisingly, Murphy remains cheerful: “Most people are extremely depressed by what I say. I’m not. Not at all. I think it’s exciting to imagine what the future can be. You’re only depressed if you’re in love with modernity. If you’re not, it’s not devastating to imagine it disappearing.”

Banner image: Installation of solar panels. Image by Trinh Trần via Pexels (Public domain).