by DGR News Service | Jan 3, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This excerpt from Chapter 4 of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet was written by Lierre Keith. Click the link above to purchase the book or read online for free.

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

—Mary Oliver, poet

The culture of the left needs a serious overhaul. At our best and bravest moments, we are the people who believe in a just world; who fight the power with all the courage and commitment that women and men can possess; who refuse to be bought or beaten into submission, and refuse equally to sell each other out. The history of struggles for justice is inspiring, ennobling even, and it should encourage us to redouble our efforts now when the entire world is at stake. Instead, our leadership is leading us astray. There are historic reasons for the misdirection of many of our movements, and we would do well to understand those reasons before it’s too late.1

The history of misdirection starts in the Middle Ages when various alternative sects arose across Europe, some more strictly religious, some more politically utopian. The Adamites, for instance, originated in North Africa in the second century, and the last of the Neo-Adamites were forcibly suppressed in Bohemia in 1849.2 They wanted to achieve a state of primeval innocence from sin. They practiced nudism and ecstatic rituals of rebirth in caves, rejected marriage, and held property communally. Groups such as the Diggers (True Levelers) were more political. They argued for an egalitarian social structure based on small agrarian communities that embraced ecological principles. Writes one historian, “They contended that if only the common people of England would form themselves into self-supporting communes, there would be no place in such a society for the ruling classes.”3

Not all dissenting groups had a political agenda. Many alternative sects rejected material accumulation and social status but lacked any clear political analysis or egalitarian program. Such subcultures have repeatedly arisen across Europe, coalescing around a common constellation of themes:

■ A critique of the dogma, hierarchy, and corruption of organized religion;

■ A rejection of the moral decay of urban life and a belief in the superiority of rural life;

■ A romantic or even sentimental appeal to the past: Eden, the Golden Age, pre-Norman England;

■ A millenialist bent;

■ A spiritual practice based on mysticism; a direct rather than mediated experience of the sacred. Sometimes this is inside a Christian framework; other examples involve rejection of Christianity. Often the spiritual practices include ecstatic and altered states;

■ Pantheism and nature worship, often concurrent with ecological principles, and leading to the formation of agrarian communities;

■ Rejection of marriage. Sometimes sects practice celibacy; others embrace polygamy, free love, or group marriage.

Within these dissenting groups, there has long been a tension between identifying the larger society as corrupt and naming it unjust. This tension has been present for over 1,000 years. Groups that critique society as degenerate or immoral have mainly responded by withdrawing from society. They want to make heaven on Earth in the here and now, abandoning the outside world. “In the world but not of it,” the Shakers said. Many of these groups were and are deeply pacifistic, in part because the outside world and all things political are seen as corrupting, and in part for strongly held moral reasons. “Corruption groups” are not always leftist or progressive. Indeed, many right-wing and reactionary elements have formed sects and founded communities. In these groups, the sin in urban or modern life is hedonism, not hierarchy. In fact, these groups tend to enforce strict hierarchy: older men over younger men, men over women. Often they have a charismatic leader and the millenialist bent is quite marked.

“Justice groups,” on the other hand, name society as inequitable rather than corrupt, and usually see organized religion as one more hierarchy that needs to be dismantled. They express broad political goals such as land reform, pluralistic democracy, and equality between the sexes. These more politically oriented spiritual groups walk the tension between withdrawal and engagement. They attempt to create communities that support a daily spiritual practice, allow for the withdrawal of material participation in unjust systems of power, and encourage political activism to bring their New Jerusalem into being. Contemporary groups like the Catholic Workers are attempts at such a project.

This perennial trend of critique and utopian vision was bolstered by Romanticism, a cultural and artistic movement that began in the latter half of the eighteenth century in Western Europe. It was at least partly a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, which valued rationality and science. The image of the Enlightenment was the machine, with the living cosmos reduced to clockwork. As the industrial revolution gained strength, rural lifeways were destroyed while urban areas swelled with suffering and squalor. Blake’s dark, Satanic mills destroyed rivers, the commons of wetlands and forests fell to the highest bidder, and coal dust was so thick in London that the era could easily be deemed the Age of Tuberculosis. In Germany, the Rhine and the Elbe were killed by dye works and other industrial processes. And along with natural communities, human communities were devastated as well.

Romanticism revolved around three main themes: longing for the past, upholding nature as pure and authentic, and idealizing the heroic and alienated individual. Germany, where elements of an older pagan folk culture still carried on, was in many ways the center of the Romantic movement.

How much of this Teutonic nature worship was really drawn from surviving pre-Christian elements, and how much was simply a Romantic recreation—the Renaissance Faire of the nineteenth century—is beyond the scope of this book. Suffice it to say, there were enough cultural elements for the Romantics to build on.

In 1774, German writer Goethe penned the novel The Sorrows of Young Werther, the story of a young man who visits an enchanting peasant village, falls in love with an unattainable young woman, and suffers to the point of committing suicide. The book struck an oversensitive nerve, and, overnight, young men across Europe began modeling themselves on the protagonist, a depressive and passionate artist. Add to this the supernatural and occult elements of Edgar Allan Poe’s work, and, by the nineteenth century, the Romantics of that day resembled modern Goths. A friend of mine likes to say that history is same characters, different costumes—and in this case the costumes haven’t even changed much.4

Another current of Romanticism that eventually influenced our current situation was bolstered by philosopher Jean Jacques Rosseau,5 who described a “state of nature” in which humans lived before society developed. He was not the creator of the image of the noble savage—that dubious honor falls to John Dryden, in his 1672 play The Conquest of Granada. Rousseau did, however, popularize one of the core components that would coalesce into the cliché, arguing that there was a fundamental rupture between human nature and human society. The concept of such a divide is deeply problematical, as by definition it leaves cultures that aren’t civilizations out of the circle of human society. Whether the argument is for the bloodthirsty savage or the noble savage, the underlying concept of a “state of nature” places hunter-gatherers, horticulturalists, nomadic pastoralists, and even some agriculturalists outside the most basic human activity of creating culture. All culture is a human undertaking: there are no humans living in a “state of nature.”6 With the idea of a state of nature, vastly different societies are collapsed into an image of the “primitive,” which exists unchanging outside of history and human endeavor.

Indeed, one offshoot of Romanticism was an artistic movement called Primitivism that inspired its own music, literature, and art. Romanticism in general and Primitivism in particular saw European culture as overly rational and repressive of natural impulses. So-called primitive cultures, in contrast, were cast as emotional, innocent and childlike, sexually uninhibited, and at one with the natural world. The Romantics embraced the belief that “primitives” were naturally peaceful; the Primitivists tended to believe in their proclivity to violence. Either cliché could be made to work because the entire image is a construct bearing no relation to the vast variety of forms that indigenous human cultures have taken. Culture is a series of choices—political choices made by a social animal with moral agency. Both the noble savage and the bloodthirsty savage are objectifying, condescending, and racist constructs.

Romanticism tapped into some very legitimate grievances. Urbanism is alienating and isolating. Industrialization destroys communities, both human and biotic. The conformist demands of hierarchical societies leave our emotional lives inauthentic and numb, and a culture that hates the animality of our bodies drives us into exile from our only homes. The realization that none of these conditions are inherent to human existence or to human society can be a profound relief. Further, the existence of cultures that respect the earth, that give children kindness instead of public school, that share food and joy in equal measure, that might even have mystical technologies of ecstasy, can serve as both an inspiration and as evidence of the crimes committed against our hearts, our culture, and our planet. But the places where Romanticism failed still haunt the culture of the left today and must serve as a warning if we are to build a culture of resistance that can support a true resistance movement.

In Germany, the combination of Romanticism and nationalism created an upswell of interest in myths. They spurred a widespread longing for an ancient or even primordial connection with the German landscape. Youth are the perennially disaffected and rebellious, and German youth in the late nineteenth century coalesced into their own counterculture. They were called Wandervogel or wandering spirits. They rejected the rigid moral code and work ethic of their bourgeois parents, romanticized the image of the peasant, and wandered the countryside with guitars and rough-spun tunics. The Wandervogel started with urban teachers taking their students for hikes in the country as part of the Lebensreform (life reform) movement. This social movement emphasized physical fitness and natural health, experimenting with a range of alternative modalities like homeopathy, natural food, herbalism, and meditation. The Lebensreform created its own clinics, schools, and intentional communities, all variations on a theme of reestablishing a connection with nature. The short hikes became weekends; the weekends became a lifestyle. The Wandervogel embraced the natural in opposition to the artificial: rural over urban, emotion over rationality, sunshine and diet over medicine, spontaneity over control. The youth set up “nests” and “antihomes” in their towns and occupied abandoned castles in the forests. The Wandervogel was the origin of the youth hostel movement. They sang folk songs; experimented with fasting, raw foods, and vegetarianism; and embraced ecological ideas—all before the year 1900. They were the anarchist vegan squatters of the age.

Environmental ideas were a fundamental part of these movements. Nature as a spiritual source was fundamental to the Romantics and a guiding principle of Lebensreform. Adolph Just and Benedict Lust were a pair of doctors who wrote a foundational Lebensreform text, Return to Nature, in 1896. In it, they decried,

Man in his misguidance has powerfully interfered with nature. He has devastated the forests, and thereby even changed the atmospheric conditions and the climate. Some species of plants and animals have become entirely extinct through man, although they were essential in the economy of Nature. Everywhere the purity of the air is affected by smoke and the like, and the rivers are defiled. These and other things are serious encroachments upon Nature, which men nowadays entirely overlook but which are of the greatest importance, and at once show their evil effect not only upon plants but upon animals as well, the latter not having the endurance and power of resistance of man.7

Alternative communities soon sprang up all over Europe. The small village of Ascona, Switzerland, became a countercultural center between 1900 and 1920. Experiments involved “surrealism, modern dance, dada, Paganism, feminism, pacifism, psychoanalysis and nature cure.”8 Some of the figures who passed through Ascona included Carl Jung, Isadora Duncan, Mikhail Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, and an alcoholic Herman Hesse seeking a cure. Clearly, social change—indeed, revolution—was one of the ideas on the table at Ascona. This chaos of alternative spiritual, cultural, and political trends began to make its way to the US. On August 20, 1903, for instance, an anarchist newspaper in San Francisco published a long article describing the experiments underway at Ascona.

As we will see, the connections between the Lebensreform, Wandervogel youth, and the 1960s counterculture in the US are startlingly direct. German Eduard Baltzer wrote a lengthy explication of naturliche lebensweise (natural lifestyle) and founded a vegetarian community. Baltzer-inspired painter Karl Wihelm Diefenbach, who also started a number of alternative communities and workshops dedicated to religion, art, and science, all based on Lebensreform ideas. Artists Gusto Graser and Fidus pretty well created the artistic style of the German counterculture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Viewers of their work would be forgiven for thinking that their paintings of psychedelic colors, swirling floraforms, and naked bodies embracing were album covers circa 1968. Fidus even used the iconic peace sign in his art.

Graser was a teacher and mentor to Herman Hesse, who was taken up by the Beatniks. Siddhartha and Steppenwolf were written in the 1920s but sold by the millions in the US in the 1960s. Declares one historian, “Legitimate history will always recount Hesse as the most important link between the European counter-culture of his [Hesse’s] youth and their latter-day descendants in America.”9

Along with a few million other Europeans, some of the proponents of the Wandervogel and Lebensreform movements immigrated to the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century. The most famous of these Lebensreform immigrants was Dr. Benjamin Lust, deemed the Father of Naturopathy, quoted previously. Write Gordon Kennedy and Kody Ryan, “Everything from massage, herbology, raw foods, anti-vivisection and hydro-therapy to Eastern influences like Ayurveda and Yoga found their way to an American audience through Lust.”10 In Return To Nature, he railed against water and air pollution, vivisection, vaccination, meat, smoking, alcohol, coffee, and public schooling. Any of this sound a wee bit familiar? Gandhi, a fan, was inspired by Lust’s principles to open a Nature Cure clinic in India.

The emphasis on sunshine and naturism led many of these Lebensreform immigrants to move to warm, sunny California and Florida. Sun worship was embraced as equal parts ancient Teutonic religion, health-restoring palliative, and body acceptance. It was much easier to live outdoors and scrounge for food where the weather never dropped below freezing. Called Nature Boys, naturemensch, and modern primitives, they set up camp and began attracting followers and disciples. German immigrant Arnold Ehret, for instance, wrote a number of books on fasting, raw foods, and the health benefits of nude sunbathing, books that would become standard texts for the San Francisco hippies. Gypsy Boots was another direct link from the Lebensreform to the hippies. Born in San Francisco, he was a follower of German immigrant Maximillian Sikinger. After the usual fasting, hiking, yoga, and sleeping in caves, he opened his “Health Hut” in Los Angeles, which was surprisingly successful. He was also a paid performer at music festivals like Monterey and Newport in 1967 and 1968, appearing beside Jefferson Airplane, Jimi Hendrix, and the Grateful Dead. Carolyn Garcia, Jerry’s wife, was apparently a big admirer. Boots was also in the cult film Mondo Hollywood with Frank Zappa.

The list of personal connections between the Wandervogel Nature Boys and the hippies is substantial, and makes for an unbroken line of cultural continuity. But before we turn to the 1960s, it’s important to examine what happened to the Lebensreform and Wandervogel in Germany with the rise of Nazism.

This is not easy to do. Fin de siècle Germany was a tumult of change and ideas, pulling in all directions. There was a huge and politically powerful socialist party, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (Social Democratic Party of Germany), or SPD, which one historian called “the pride of the Second International.”11 In 1880, it garnered more votes than any other party in Germany, and, in 1912, it had more seats in Parliament than any other party. It helped usher in the first parliamentary democracy, including universal suffrage, and brought a shorter workday, legal workers’ councils in industry, and a social safety net. To these serious activists, the Wandervogel and Lebensreform, especially “the more manifestly idiotic of these cults,”12 were fringe movements. To state the obvious, the constituents of SPD were working-class and poor people concerned with survival and justice, while the Lebensreform, with their yoga, spiritualism, and dietary silliness, were almost entirely middle class.

Here we begin to see these utopian ideas take a sinister turn. The seeds of contradiction are easy to spot in the völkisch movement entry on Wikipedia, which states, “The völkisch movement is the German interpretation of the populist movement, with a romantic focus on folklore and the ‘organic.’ . . . In a narrow definition it can be used to designate only groups that consider human beings essentially preformed by blood, i.e. inherited character.”

Immediately, there are problems. The völkisch is marked with a Nazi tag. One Wikipedian writes, “Personally I consider it offensive to claim that an ethnic definition of ‘Folk’ equals Nationalism and/or Racism.” Another Wikipedian points out that the founders of the völkisch concept were leftist thinkers. Another argues, “With regard to its origins . . . the völkisch idea is wholeheartedly non-racist, and people like Landauer and Mühsam (the leading German anarchists of their time) represented a continuing current of völkisch anti-racism. It’s understandable if the German page focuses on the racist version—a culture of guilt towards Romanticism seems to be one of Hitler’s legacies—but these other aspects need to be looked at too.”13

Who is correct? Culture, ethnicity, folklore, and nationalism are all strands that history has woven into the word. But völk does have a first philosopher, Johann Gottfried von Herder, who founded the whole idea of folklore, of a culture of the common people that should be valued, not despised. He urged Germans to take pride in their language, stories, art, and history. The populist appeal in his ideas—indeed, their necessity to any popular movement—may seem obvious to us 200 years later, but at the time this valuing of a people’s culture was new and radical. His personal collection of folk poetry inspired a national hunger for folklore; the brothers Grimm were one direct result of Herder’s work. He also argued that everyone from the king to the peasants belonged to the völk, a serious break with the ruling notion that only the nobility were the inheritors of culture and that that culture should emulate classical Greece. He believed that his conception of the völk would lead to democracy and was a supporter of the French Revolution.

Herder was very aware of where the extremes of nationalism could lead and argued for the full rights of Jews in Germany. He rejected racial concepts, saying that language and culture were the distinctions that mattered, not race, and asserted that humans were all one species. He wrote, “No nationality has been solely designated by God as the chosen people of the earth; above all we must seek the truth and cultivate the garden of the common good.”14

Another major proponent of leftist communitarianism was Gustav Landauer, a Jewish German. He was one of the leading anarchists through the Wilhelmine era until his death in 1919 when he was arrested by the Freikorps and stoned to death. He was a mystic as well as being a political writer and activist. His biographer, Eugene Lunn, describes Landauer’s ideas as a “synthesis of völkisch romanticism and libertarian socialism,” hence, “romantic socialism.”15 He was also a pacifist, rejecting violence as a means to revolution both individually and collectively. His belief was that the creation of libertarian communities would “gradually release men and women from their childlike dependence upon authority,” the state, organized religion, and other forms of hierarchy.16 His goal was to build “radically democratic, participatory communities.”17

Landauer spoke to the leftist writers, artists, intellectuals, and youths who felt alienated by modernity and urbanism and expressed a very real need—emotional, political, and spiritual—for community renewal. He had a full program for the revolutionary transformation of society. Rural communes were the first practical step toward the end of capitalism and exploitation. These communities would form federations and work together to create the infrastructure of a new society based on egalitarian principles. It was an A to B plan that never lost sight of the real conditions of oppression under which people were living. After World War I, roughly one hundred communes were formed in Germany, and, of those, thirty were politically leftist, formed by anarchists or communists. There was also a fledgling women’s commune movement whose goal was an autonomous feminist culture, similar to the contemporary lesbian land movement in the US.

Where did this utopian resistance movement go wrong? The problem was that it was, as historian Peter Weindling puts it, “politically ambivalent.”18 Writes Weindling, “The outburst of utopian social protest took contradictory artistic, Germanic volkish, or technocratic directions.”19 Some of these directions, unhitched from a framework of social justice, were harnessed by the right, and ultimately incorporated into Nazi ideology. Lebensreform activities like hiking and eating whole-grain bread were seen as strengthening the political body and were promoted by the Nazis. “A racial concept of health was central to National Socialism,” writes Weindling. Meanwhile, Jews, gays and lesbians, the mentally ill, and anarchists were seen as “diseases” that weakened the Germanic race as a whole.

Ecological ideas were likewise embraced by the Nazis. The health and fitness of the German people—a primary fixation of Nazi culture—depended on their connection to the health of the land, a connection that was both physical and spiritual. The Nazis were a peculiar combination of the Romantic and the Modern, and the backward-looking traditionalist and the futuristic technotopians were both attracted to their ideology. The Nazi program was as much science as it was emotionality. Writes historian David Blackborn,

National socialism managed to reconcile, at least theoretically, two powerful and conflicting impulses of the later nineteenth century, and to benefit from each. One was the infatuation with the modern and the technocratic, where there is evident continuity from Wilhelmine Germany to Nazi eugenicists and Autobahn builders; the other was the “cultural revolt” against modernity and machine-civilization, pressed into use by the Nazis as part of their appeal to educated élites and provincial philistines alike.20

Let’s look at another activist of the time, one who was political. Erich Mühsam, a German Jewish anarchist, was a writer, poet, dramatist, and cabaret performer. He was a leading radical thinker and agitator during the Weimar Republic, and won international acclaim for his dramatic work satirizing Hitler. He had a keen interest in combining anarchism with theology and communal living, and spent time in the alternative community of Ascona. Along with many leftists, he was arrested by the Nazis and sent to concentration camps in Sonnenburg, Brandenburg, and finally Oranienburg. Intellectuals around the world protested and demanded Mühsam’s release, to no avail. When his wife Zenzl was allowed to visit him, his face was so bruised she didn’t recognize him. The guards beat and tortured him for seventeen months. They made him dig his own grave. They broke his teeth and burned a swastika into his scalp. Yet when they tried to make him sing the Nazi anthem, he would sing the International instead. At his last torture session, they smashed in his skull and then killed him by lethal injection. They finished by hanging his body in a latrine.

The intransigent aimlessness and anemic narcissism of so much of the contemporary counterculture had no place beside the unassailable courage and sheer stamina of this man. Sifting through this material, I will admit to a certain amount of despair: between the feckless and the fascist, will there ever be any hope for this movement? The existence of Erich Mühsam is an answer to embrace. Likewise, reading history backwards, so that Nazis are preordained in the völkish idea, is insulting to the inheritors of this idea who resisted Fascism with Mühsam’s fortitude. There were German leftists who fought for radical democracy and justice, not despite their communitarianism, but with it.

Our contemporary environmental movement has much to learn from this history. Janet Biehl and Peter Staudenmaier, in their book Ecofascism: Lessons from the German Experience,21 explore the idea that fascism or other reactionary politics are “perhaps the unavoidable trajectory of any movement which acknowledges and opposes social and ecological problems but does not recognize their systemic roots or actively resist the political and economic structures which generate them. Eschewing societal transformation in favor of personal change, an ostensibly apolitical disaffection can, in times of crisis, yield barbaric results.”22

The contemporary alterna-culture won’t result in anything more sinister than silliness; fascism in the US is most likely to come from actual right-wing ideologues mobilizing the resentments of the disaffected and economically stretched mainstream, not from New Age workshop hoppers. And friends of Mary Jane aren’t known for their virulence against anything besides regular bathing. German immigrants brought the Lebensreform and Wandervogel to the US, and it didn’t seed a fascist movement here. None of this leads inexorably to fascism. But we need to take seriously the history of how ideas which we think of as innately progressive, like ecology and animal rights, became intertwined with a fascist movement.

An alternative culture built around the project of an individualistic and interior experience, whether spiritual or psychological, cannot create a resistance movement, no matter how many societal conventions it trespasses. Indeed, the Wandervogel manifesto stated, “We regard with contempt all who call us political,”23 and their most repeated motto was “Our lack of purpose is our strength.” But as Laqueur points out,

Lack of interest in public affairs is not civic virtue, and . . . an inability to think in political categories does not prevent people from getting involved in political disaster . . . The Wandervogel . . . completely failed. They did not prepare their members for active citizenship. . . . Both the socialist youth and the Catholics had firmer ground under their feet; each had a set of values to which they adhered. But in the education of the free youth movement there was a dangerous vacuum all too ready to be filled by moral relativisim and nihilism.24

We are facing another disaster, and if we fail there will be no future to learn from our mistakes. That same “lack of interest”—often a stance of smug alienation—is killing our last chance of resistance. We are not preparing a movement for active citizenship and all that implies—the commitment, courage, and sacrifice that real resistance demands. There is no firm moral ground under the feet of those who can only counsel withdrawal and personal comfort in the face of atrocity. And the current Wandervogel end in nihilism as well, repeating that it’s over, we can do nothing, the human race has run its course and the bacteria will inherit the earth. The parallels are exact. And the outcome?

The Wandervogel marched off to World War I, where they “perished in Flanders and Verdun.”25 Of those who returned from the war, a small, vocal minority became communists. A larger group embraced right-wing protofascist groups. But the largest segment was apolitical and apathetic. “This was no accidental development,” writes Laqueur.26

The living world is now perishing in its own Flanders and Verdun, a bloody, senseless pile of daily species. Today there are still wood thrushes, small brown angels of the deep woods. Today there are northern leopard frogs, but only barely. There may not be Burmese star tortoises, with their shells like golden poinsettias; the last time anyone looked—for 400 hours with trained dogs—they only found five. If the largest segment of us remains apolitical and apathetic, they we’ll all surely die.

Part II will be published next week. For references, visit this link to read the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet online or to purchase a copy.

by DGR News Service | Dec 13, 2019 | Direct Action

This post is excerpted from the book, Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. Click here to buy a copy of the book or read it online. The book includes a detailed exploration of the morality of different forms of resistance, and is highly recommended reading. This is part 3 in a series. Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here.

Ultimately, success requires direct confrontation and conflict with power; you can’t win on the defensive. But direct confrontation doesn’t always mean overt confrontation. Disrupting and dismantling systems of power doesn’t require advertising who you are, when and where you are planning to act, or what means you will use.

Back in the heyday of the summit-hopping “anti-globalization” movement, I enjoyed seeing the Black Bloc in action. But I was discomfited when I saw them smash the windows of a Gap storefront, a Starbucks, or even a military recruiting office during a protest. I was not opposed to seeing those windows smashed, just surprised that those in the Black Bloc had deliberately waited until the one day their targets were surrounded by thousands of heavily armed riot police, with countless additional cameras recording their every move and dozens of police buses idling on the corner waiting to take them to jail. It seemed to be the worst possible time and place to act if their objective was to smash windows and escape to smash another day.

Of course, their real aim wasn’t to smash windows—if you wanted to destroy corporate property there are much more effective ways of doing it—but to fight. If they wanted to smash windows, they could have gone out in the middle of the night a few days before the protest and smashed every corporate franchise on the block without anyone stopping them. They wanted to fight power, and they wanted people to see them doing it. But we need to fight to win, and that means fighting smart. Sometimes that means being more covert or oblique, especially if effective resistance is going to trigger a punitive response.

That said, actions can be both effective and draw attention. Anarchist theorist and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin argued that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.” The intent of the deed is not to commit a symbolic act to get attention, but to carry out a genuinely meaningful action that will serve as an example to others.

Four Methods of Direct Confrontation

There are four basic ways to directly confront those in power. Three deal with land, property, or infrastructure, and one deals specifically with human beings. They include:

- Obstruction and occupation;

- Reclamation and expropriation;

- Property and material destruction (threats or acts); and

- Violence against humans (threats or acts)

In other words, in a physical confrontation, the resistance has three main options for any (nonhuman) target: block it, take it, or break it.

Nondestructive Obstruction or Occupation

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful . . . tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Reclamation and Expropriation

The second means of direct conflict is reclamation and expropriation—take it. Instead of blocking the use of land or property, the resistance takes it for their own use. For example, the Landless Workers Movement—centered in Brazil, a country renowned for unjust land distribution—occupies “underused” rural farmland (typically owned by wealthy absentee landlords) and sets up farming villages for landless or displaced people. Thanks to a land reform clause in the Brazilian constitution, the occupiers have been able to compel the government to expropriate the land and give them title. The movement has also engaged in direct action like blockades, and has set up its own education and literacy programs, as well as sustainable agriculture initiatives. The Landless Workers Movement is considered the largest social movement in Latin America, with an estimated 1.5 million members.

Expropriation has been a common tactic in various stages of revolution. “Loot the looters!” proclaimed the Bolsheviks during Russia’s October Revolution. Early on, the Bolsheviks staged bank robberies to acquire funds for their cause. Successful revolutionaries, as well as mainstream leftists, have also engaged in more “legitimate” activities, but these are no less likely to trigger reprisals. When the democratically elected government of Iran nationalized an oil company in 1953, the CIA responded by staging a coup. And, of course, guerilla movements commonly “liberate” equipment from occupiers in order to carry out their own activities.

Property and Material Destruction

The third means of direct conflict is property and material destruction—break it. This category includes sabotage. Some say the word sabotage comes from early Luddites tossing wooden shoes (sabots) into machinery, stopping the gears. But the term probably comes from a 1910 French railway strike, when workers destroyed the wooden shoes holding the rails—a good example of moving up the infrastructure. And sabotage can be more than just physical damage to machines; labor activism has long included work slowdowns and deliberate bungling.

Sabotage is an essential part of war and resistance to occupation. This is widely recognized by armed forces, and the US military has published a number of manuals and pamphlets on sabotage for use by occupied people. The Simple Sabotage Field Manual published by the Office of Strategic Services during World War II offers suggestions on how to deploy and motivate saboteurs, and specific means that can be used. “Simple sabotage is more than malicious mischief,” it warns, “and it should always consist of acts whose results will be detrimental to the materials and manpower of the enemy.” It warns that a saboteur should never attack targets beyond his or her capacity, and should try to damage materials in use, or destined for use, by the enemy. “It will be safe for him to assume that almost any product of heavy industry is destined for enemy use, and that the most efficient fuels and lubricants also are destined for enemy use.” It encourages the saboteur to target transportation and communications systems and devices in particular, as well as other critical materials for the functioning of those systems and of the broader occupational apparatus. Its particular instructions range from burning enemy infrastructure to blocking toilets and jamming locks, from working slowly or inefficiently in factories to damaging work tools through deliberate negligence, from spreading false rumors or misleading information to the occupiers to engaging in long and inefficient workplace meetings.

Ever since the industrial revolution, targeting infrastructure has been a highly effective means of engaging in conflict. It may be surprising to some that the end of the American Civil War was brought about in large part by attacks on infrastructure. From its onset in 1861, the Civil War was extremely bloody, killing more American combatants than all other wars before or since, combined. After several years of this, President Lincoln and his chief generals agreed to move from a “limited war” to a “total war” in an attempt to decisively end the war and bring about victory.

Historian Bruce Catton described the 1864 shift, when Union general “[William Tecumseh] Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructures.” Catton writes that “it was also the nineteenth-century equivalent of the modern bombing raid, a blow at the civilian underpinning of the military machine. Bridges, railroads, machine shops, warehouses—anything of this nature that lay in Sherman’s path was burned or dismantled.” Telegraph lines were targeted as well, but so was the agricultural base. The Union Army selectively burned barns, mills, and cotton gins, and occasionally burned crops or captured livestock. This was partly an attack on agriculture-based slavery, and partly a way of provisioning the Union Army while undermining the Confederates. These attacks did take place with a specific code of conduct, and General Sherman ordered his men to distinguish “between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.”

Catton argues that military engagements were “incidental” to the overall goal of striking the infrastructure, a goal which was successfully carried out. As historian David J. Eicher wrote, “Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South’s potential and psychology to wage war.” The strategy was crucial to the northern victory.

Violence Against Humans

The fourth and final means of direct conflict is violence against humans. Here we’re using violence specifically and explicitly to mean harm or injury to living creatures. Smashing a window, of course, is not violence; violence does include psychological harm or injury. The vast majority of resistance movements know the importance of violence in self-defense. Malcolm X was typically direct: “We are nonviolent with people who are nonviolent with us.”

In resistance movements, offensive violence is rare—virtually all violence used by historical resistance groups, from revolting slaves to escaping concentration camp prisoners to women shooting abusive partners, is a response to greater violence from power, and so is both justifiable and defensive. When prisoners in the Sobibór extermination camp quietly SS killed guards in the hours leading up to their planned escape, some might argue that they committed acts of offensive violence. But they were only responding to much more extensive violence already committed by the Nazis, and were acting to avert worse violence in the immediate future.

There have been groups which engaged in systematic offensive violence and attacks directed at people rather than infrastructure. The Red Army Faction (RAF) was a militant leftist group operating in West Germany, mostly in the 1970s and 1980s. They carried out a campaign of bombings and assassination attempts mostly aimed at police, soldiers, and high-ranking government or business officials. Another example would be the Palestinian group Hamas, which has carried out a large number of violent attacks on both civilians and military personnel in Israel. (It is also a political party and holds a legally elected majority in the Palestinian National Authority. It’s often ignored that much of Hamas’s popularity comes from its many social programs, which long predate its election to government. About 90 percent of Hamas’s activities are these social programs, which include medical clinics, soup kitchens, schools and literacy programs, and orphanages.)

It’s sometimes argued that the use of violence is never justifiable strategically, because the state will always have the larger ability to escalate beyond the resistance in a cycle of violence. In a narrow sense that’s true, but in a wider sense it’s misleading. Successful resistance groups almost never attempt to engage in overt armed conflict with those in power (except in late-stage revolutions, when the state has weakened and revolutionary forces are large and well-equipped). Guerilla groups focus on attacking where they are strongest, and those in power are weakest. The mobile, covert, hit-and-run nature of their strategy means that they can cause extensive disruption while (hopefully) avoiding government reprisals.

Furthermore, the state’s violent response isn’t just due to the use of violence by the resistance, it’s a response to the effectiveness of the resistance. We’ve seen that again and again, even where acts of omission have been the primary tactics. Those in power will use force and violence to put down any major threat to their power, regardless of the particular tactics used. So trying to avoid a violent state response is hardly a universal argument against the use of defensive violence by a resistance group.

The purpose of violent resistance isn’t simply to do violence or exact revenge, as some dogmatic critics of violence seem to believe. The purpose is to reduce the capacity of those in power to do further violence. The US guerilla warfare manual explicitly states that a “guerrilla’s objective is to diminish the enemy’s military potential.” (Remember what historian Bruce Catton wrote about the Union Army’s engagements with Confederate soldiers being incidental to their attacks on infrastructure.) To attack those in power without a strategy, simply to inflict indiscriminate damage, would be foolish.

The RAF used offensive violence, but probably not in a way that decreased the capacity of those in power to do violence. Starting in 1971, they shot two police and killed one. They bombed a US barracks, killing one and wounding thirteen. They bombed a police station, wounding five officers. They bombed the car of a judge. They bombed a newspaper headquarters. They bombed an officers’ club, killing three and injuring five. They attacked the West German embassy, killing two and losing two RAF members. They undertook a failed attack against an army base (which held nuclear weapons) and lost several RAF members. They assassinated the federal prosecutor general and the director of a bank in an attempted kidnapping. They hijacked an airliner, and three hijackers were killed. They kidnapped the chairman of a German industry organization (who was also a former SS officer), killing three police and a driver in the attack. When the government refused to give in to their demands to release imprisoned RAF members, they killed the chairman. They shot a policeman in a bar. They attempted to assassinate the head of NATO, blew up a car bomb in an air base parking lot, attempted to assassinate an army commander, attempted to bomb a NATO officer school, and blew up another car bomb in another air base parking lot. They separately assassinated a corporate manager and the head of an East German state trust agency. And as their final militant act, in 1993 they blew up the construction site of a new prison, causing more than one hundred million Deutsche Marks of damage. Throughout this period, they killed a number of secondary targets such as chauffeurs and bodyguards.

Setting aside for the time being the ethical questions of using offensive violence, and the strategic implications of giving up the moral high ground, how many of these acts seem like effective ways to reduce the state’s capacity for violence? In an industrial civilization, most of those in government and business are essentially interchangeable functionaries, people who perform a certain task, who can easily be replaced by another. Sure, there are unique individuals who are especially important driving forces—people like Hitler—but even if you believe Carlyle’s Great Man theory, you have to admit that most individual police, business managers, and so on will be quickly and easily replaced in their respective organizations. How many police and corporate functionaries are there in one country? Conversely, how many primary oil pipelines and electrical transmission lines are there? Which are most heavily guarded and surveilled, bank directors or remote electrical lines? Which will be replaced sooner, bureaucratic functionaries or bus-sized electrical components? And which attack has the greatest “return on investment?” In other words, which offers the most leverage for impact in exchange for the risk undertaken?

As we’ve said many times, the incredible level of day-to-day violence inflicted by this culture on human beings and on the natural world means that to refrain from fighting back will not prevent violence. It simply means that those in power will direct their violence at different people and over a much longer period of time. The question, as ever, is which particular strategy—violent or not—will actually work.

by DGR News Service | Dec 6, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

Excerpted from the book, Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. Click here to buy a copy of the book or read it online. Part 2 in a series. Part 1 is here.

Indirect to Direct

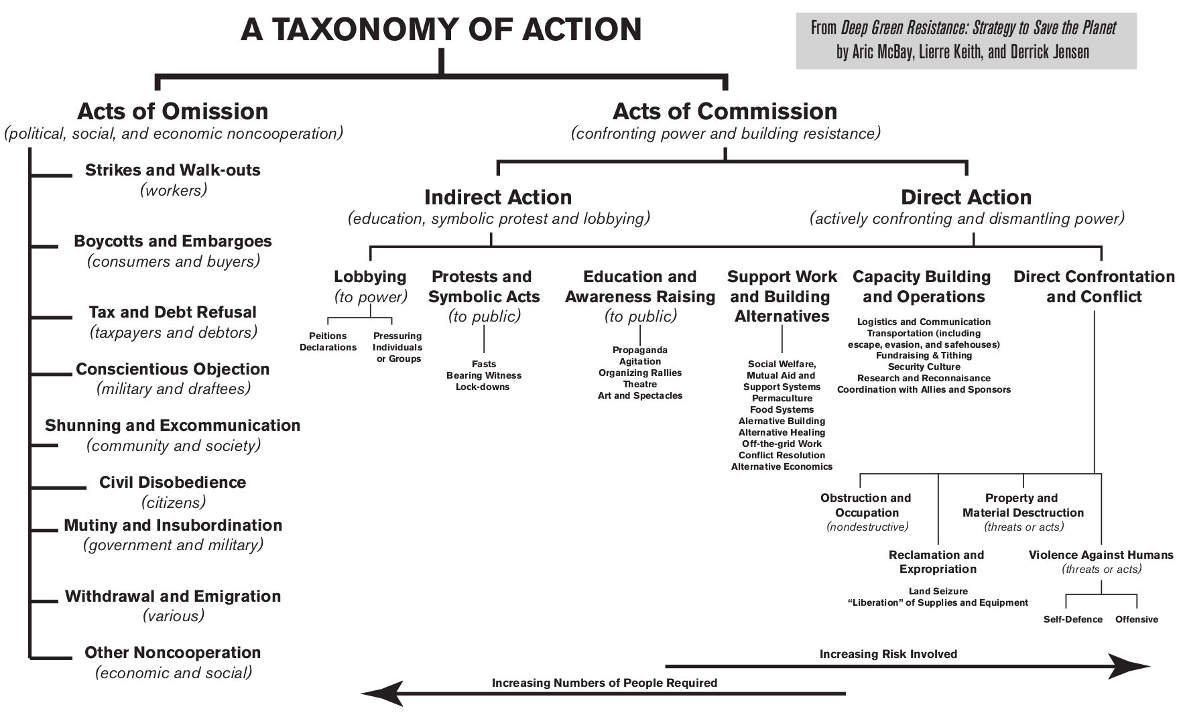

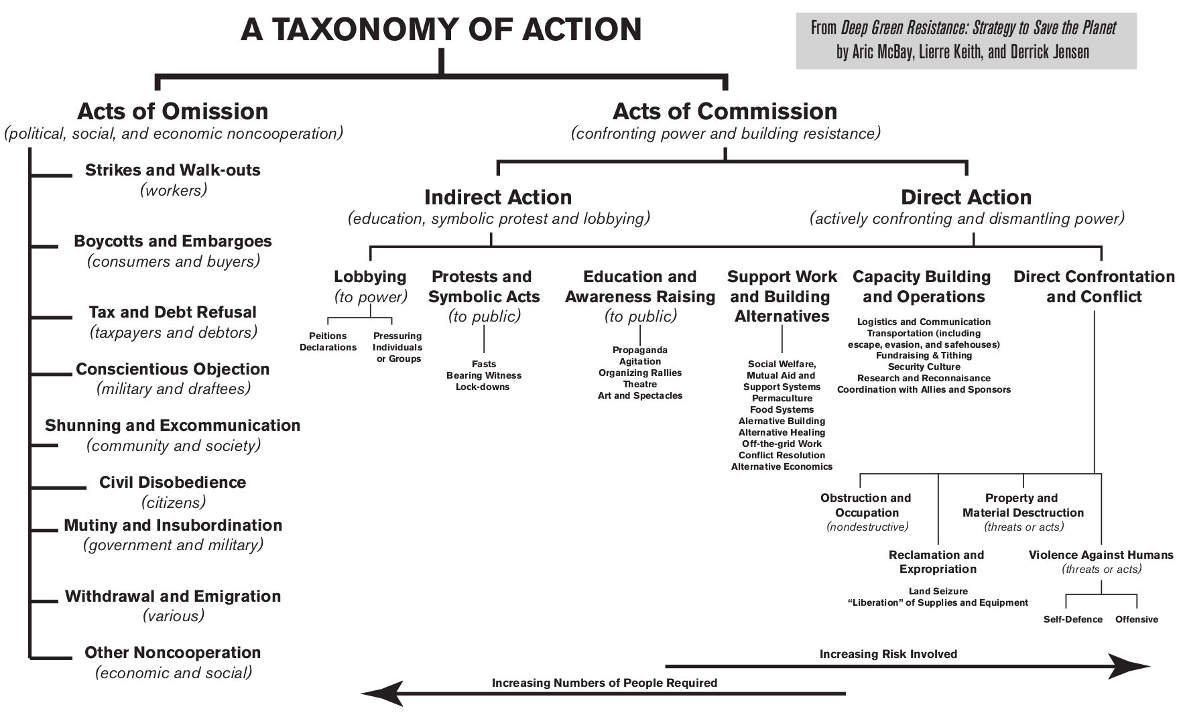

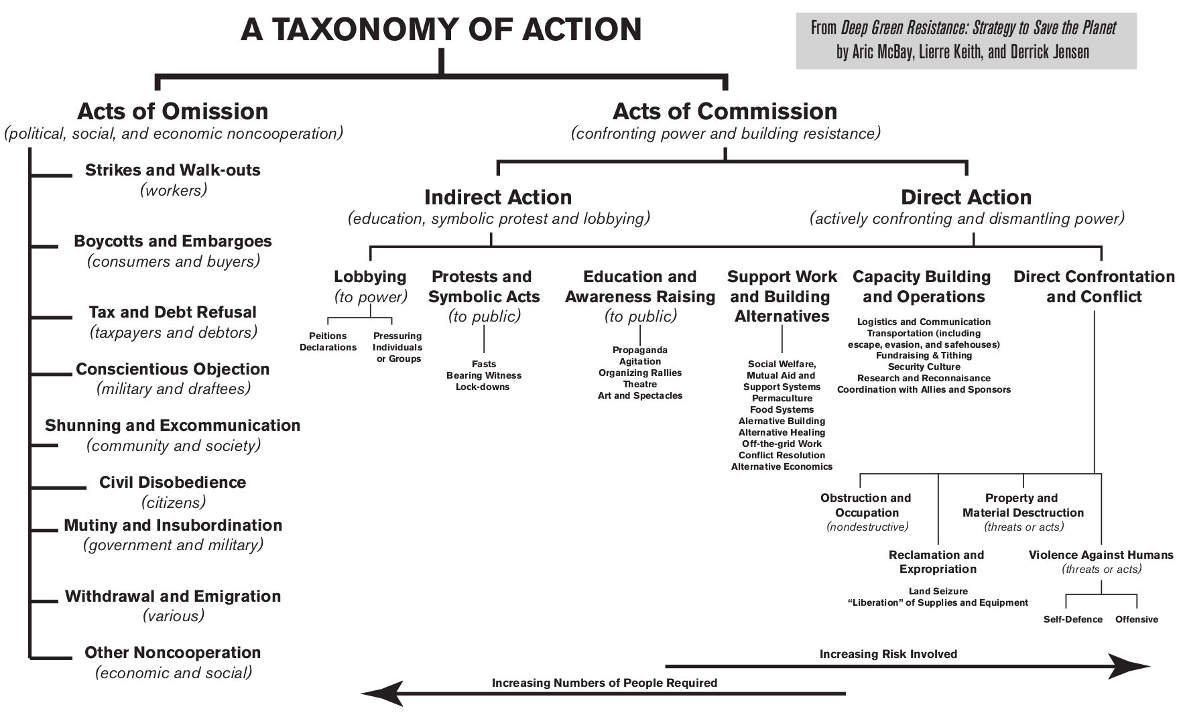

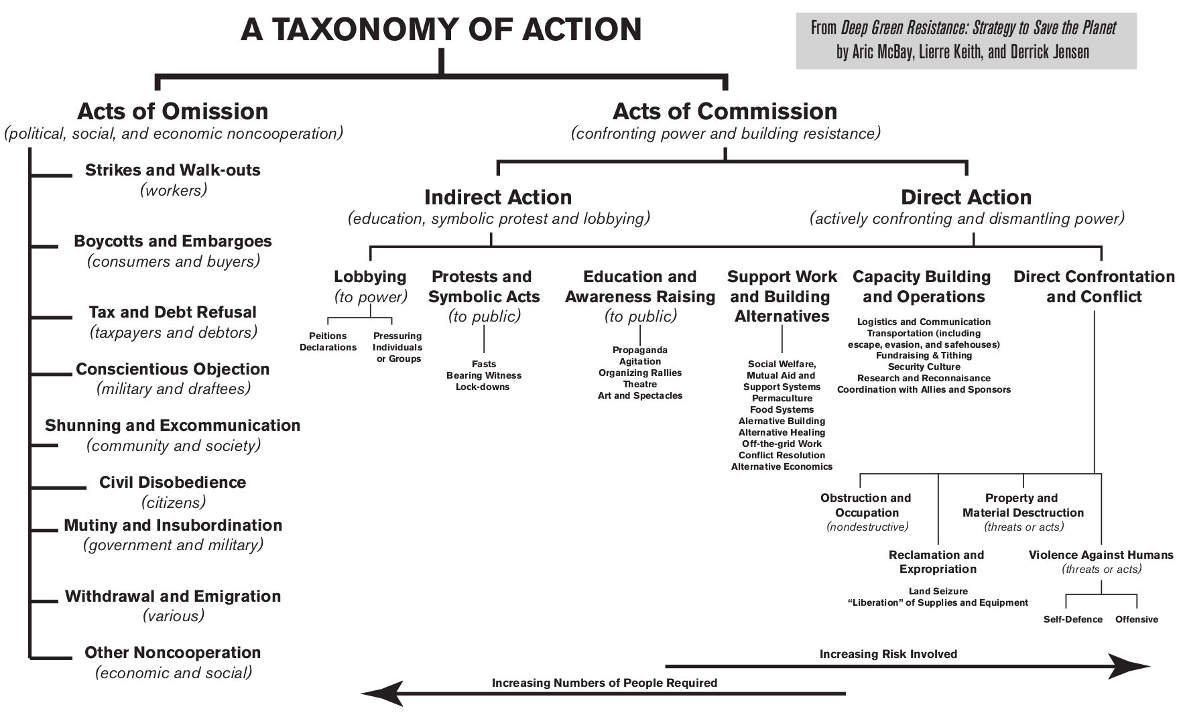

As we’ve made clear, acts of omission are not going to bring down civilization. Let’s talk about action with more potential. We can split all acts of commission into six branches:

■ lobbying;

■ protests and symbolic acts;

■ education and awareness raising;

■ support work and building alternatives;

■ capacity building and logistics;

■ and direct confrontation and conflict.

The illustration (Figure 6-1, “Taxonomy of Action,” page 243) groups them by directness. The most indirect tactics are on the left, and become progressively more direct when moving from left to right. More direct tactics involve more personal risk. (The main collective risk is failing to save the planet.) Direct acts require fewer people.

Lobbying

The first, lobbying, is attempting to influence or persuade those in power through letter writing, petitions, declarations or “speaking truth to power,” protests, and so on. For the liberal, even atrocities are just big misunderstandings.29 Lobbying informs those in power of their mistake (of course, since those in power are well-meaning, they will reform after being politely informed of their error).

Lobbying seems attractive because if you have enough resources (i.e., money), you can get government to do things for you, magnifying your actions. Success is possible when many people push for minor change, and unlikely when few people push for major change. But lobbying is too indirect—it requires us to try to convince someone to convince other people to make a decision or pass a law, which will then hopefully be enacted by other people, and enforced by yet a further group.

Lobbying via persuasion is a dead end, not just in terms of taking down civilization, but in virtually every radical endeavor. It assumes that those in power are essentially moral and can be convinced to change their behavior. But let’s be blunt: if they wanted to do the right thing, we wouldn’t be where we are now. Or to put it another way, their moral sense (if present) is so profoundly distorted they are almost all unreachable by persuasion.

And what if they could be persuaded? Capitalists employ vast armies of professional lobbyists to manipulate government. Our ability to lobby those in power (which includes heads of governments and corporations) is vastly outmatched by their ability to lobby each other. Convincing those in power to change would require huge numbers of people. If we had those people, those in power wouldn’t be convinced—they would be replaced. Convincing them to mend their ways would be irrelevant, because we could undertake much more effective action.

Lobbying is simply not a priority in taking down civilization. This is not to diminish or insult lobbying victories like the Clean Water Act and the Wildlife Act, which have bought us valuable time. It is merely to point out that lobbying will not work to topple a system as vast as civilization.

Protests and Symbolic Acts

Protests and symbolic acts are tactics used mostly to gain attention. If the intent of an action is to obstruct or disrupt business as usual in terms of transportation, the enforcement of laws, or other economic and political activities, then it’s direct confrontation. If the protest is a rally for discussion or public education, it’s education and awareness raising (see the next section).

When effective, demonstrations are part of a broader movement and go beyond the symbolic. There have been effective protests, such as the civil rights actions in Birmingham, but they were not symbolic; they were physical obstructions of business and politics. This disruption is usually illegal. Still, symbolic protests can get attention. Protests are most effective at “getting a message out” when they focus on one issue. Modern media coverage is so superficial and sensational that nuances get lost. But a critique of civilization can’t be expressed in sound bytes, so protests can’t publicize it. And civilization is so large and so ubiquitous that there is no one place to protest it. Some resistance movements have employed protests, to show strength and attract recruits, but the majority of people will never be on our side; our strategy needs to be based on effectiveness, not just numbers.

Education and Awareness Raising

All resistance groups engage in some type of education and awareness raising, often public. In the most repressive regimes, education moves underground. Propaganda, agitation, rallies, theater, art, and spectacle are all actions that fall into these categories.

For public education to work, several conditions must be met. The resistance education and propaganda must be able to outcompete the mass media. The general public must be able and willing to unravel the prevailing falsehoods, even if doing that contravenes their own social, psychological, and economic self-interest. They must have accessible ways to change their actions, and they must choose morally preferable actions over convenient ones. Unfortunately, none of these conditions are in place right now.

Another drawback of education is its built-in delay; it may take years before a given person translates new information into action. But as we know, the planet is being murdered, and the window for effective action is small. For deep green resisters, skills training and agitation may be more effective than public education.

Education won’t directly take down civilization, but it may help to radicalize and recruit people by providing a critical interpretation of their experiences. And as civilization continues to collapse, education may encourage people to question the underlying reasons for a declining economy, food crises, and so on.

Support Work

Resistance movements need internal support structures to win. This may take the physical form of sustainable local food systems, alternative construction, alternative health care, and off-the-grid energy, transport, and communications. It may also include socially focused endeavors such as mutual aid, prisoner support, conflict resolution work, alternative economics, and intentional communities.

These support structures directly enable resistance. The Quakers’ Society of Friends developed a sturdy ethic of support for the families of Quakers who were arrested under draconian conditions of religious persecution (see Chapter 5). People can take riskier (and more effective) action if they know that they and their families will be supported.

Building Alternatives

Building alternatives won’t directly bring down civilization, but as industrial civilization unravels, alternatives have two special roles. First, they can bolster resistance in times of crisis; resisters are more able to fight if they aren’t preoccupied with getting food, water, and shelter. Second, alternative communities can act as an escape hatch for regular people, so that their day-to-day work and efforts go to autonomous societies rather than authoritarian ones.

To serve either role, people building alternatives must be part of a culture of resistance—or better yet, part of a resistance movement. If the “alternative” people are aligned with civilization, their actions will prolong the destructiveness of the dominant culture. Let’s not forget that Hitler’s V2 rockets were powered by biofuel fermented from potatoes. The US military has built windmills at Guantanamo Bay, and is conducting research on hybrid and fuel-cell vehicles. Renewable energy is a necessity for a sustainable and equitable society, but not a guarantee of one. Militants and builders of alternatives are actually natural allies. As I wrote in What We Leave Behind, “If this monstrosity is not stopped, the carefully tended permaculture gardens and groves of lifeboat ecovillages will be nothing more than after-dinner snacks for civilization.” Organized militants can help such communities from being consumed.

In addition, even the most carefully designed ecovillage will not be sustainable if neighboring communities are not sustainable. As neighbors deplete their landbases, they have to look further afield for more resources, and a nearby ecovillage will surely be at the top of their list of targets for expansion. An ecovillage either has to ensure that its neighbors are sustainable or be able to repel their future efforts at expansion.

In many cultures, what might be considered an “alternative” by some people today is simply a traditional way of life—perhaps the traditional way of life. Peoples struggling with displacement from their lands and dealing with attempts at assimilation and genocide may be mostly concerned with their own survival and the survival of their way of life. And for many indigenous groups, expressing their traditional lifestyle and culture may be in itself a direct confrontation with power. This is a very different situation from people whose lives and lifestyles are not under immediate threat.

Of course, even people primarily concerned with the perpetuation of their traditional cultures and lifestyles are living with the fact that civilization has to come down for any of us to survive. People born into civilization, and those who have benefitted from its privilege, have a much greater responsibility to bring it down. Despite this, indigenous peoples are mostly fighting much harder against civilization than those born inside of it.

Every successful historical resistance movement has rested upon a subsistence base of some kind. Establishing that base is a necessary step, but that alone is not sufficient to stop the world from being destroyed.

Capacity Building and Logistics

Capacity building and logistics are the backbone of any successful resistance movement. Although direct confrontation and conflict may get the glory, no sustained campaign of direct action is possible without a healthy logistical and operational core. That includes the following:

-

- Resistance groups need ways of recruiting new members. The risk level of the group determines how open this process can be. Furthermore, new and existing members require training in tactics, strategy, logistics, and so on. Some or all of that training can take place in a lower-risk environment. Resistance movements of all kinds must be able to screen recruits or volunteers to assess their suitability and to exclude infiltrators. Members of the group must share certain essential viewpoints and values (either assured through screening or teaching) in order to maintain the group’s cohesion and focus.

- Resisters need to be able to communicate securely and rapidly with one another to share information and coordinate plans. They may also need to communicate with a wider audience, for propaganda or agitation. Many resistance groups have been defeated because of inadequate communications or poor communications security.

- Resistance requires funding, whether for offices and equipment, legal costs and bail, or underground activities. In aboveground resistance, procurement is mostly a subset of fund raising, since people can buy the items or materials they need. In underground resistance, procurement may mean getting specialized equipment without gathering attention or simply getting items the resistance otherwise would be unable to get. Of course, fund raising isn’t just a way to get materials, but also a way to support mutual aid and social welfare activities, support arrestees and casualties or their families, and allow core actionists to focus on resistance efforts rather than on “making a living.”

- People and equipment need access to transportation in order to reach other resisters and facilitate distribution of materials. Conventional means of transportation may be impaired by collapse, poverty, or social or political repression, but there are other ways. The Underground Railroad was a solid resistance transportation network. The Montgomery bus boycott was enabled by backup transportation systems (especially walking and carpooling) coordinated by civil rights organizers who scheduled carpools and even replaced worn-out shoes.

- Security is necessary for any group big enough to make a splash and become a target for state intelligence gathering and repression. Infiltration is definitely a concern, but so is ubiquitous surveillance. This does not apply solely to people or groups considering illegal action. Nonviolent, law-abiding groups have been and are surveilled and disrupted by COINTELPRO-like entities. Many times it is the aboveground resisters who are more at risk as working aboveground means being identifiable.

- Research and reconnaissance are equally important logistical tools. To be effective, any strategy requires critical information about potential targets. This is true whether a group is planning to boycott a corporation, blockade a factory, or take out a dam. Imagine how foolish you’d feel if you organized a huge boycott against some military contractor, only to find that they’d recently converted to making school buses. Resistance researchers can help develop a strategy and identify potential targets and weaknesses, as well as tactics likely to be useful against them. Research is also needed to gain an understanding of the strategy and tactics of those in power.

- There are certain essential services and care that keep a resistance movement running smoothly. These include services like the repair of equipment, clothing, and so on. Health care skills and equipment can be extremely valuable, and resistance groups should have at least basic health care capabilities, including first aid and rudimentary emergency medicine, wound care, and preventative medicine.

- Coordination with allies and sponsors is often a logistical concern. Many historical guerilla and insurgent groups have been “sponsored” by other established revolutionary regimes or by states hoping to foment revolution and undermine unfriendly foreign governments. For example, in 1965 Che Guevera left postrevolutionary Cuba to help organize and train Congolese guerillas, and Cuba itself had the backing of Soviet Russia. Both Russia and the United States spent much of the Cold War “sponsoring” various resistance groups by training and arming them, partly as a method of trying to put “friendly” governments in power, and partly as a means of waging proxy wars against each other. Resistance groups can also have sponsors and allies who are genuinely interested in supporting them, rather than attempting to manipulate them. Resistance in WWII Europe is a good example. State-sponsored armed partisan groups and other partisan and underground groups supported resistance fighters such as those in the Warsaw Ghetto.

by DGR News Service | Dec 4, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

Excerpted from the book, Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. Click here to buy a copy of the book or read it online.

We’ve all seen biological taxonomies, which categorize living organisms by kingdom and phylum down to genus and species. Though there are tens of millions of living species of vastly different shapes, sizes, and habitats, we can use a taxonomy to quickly zero in on a tiny group.

When we seek effective strategies and tactics, we have to sort through millions of past and potential actions, most of which are either historical failures or dead ends. We can save ourselves a lot of time and a lot of anguish with a quick and dirty resistance taxonomy. By looking over whole branches of action at once we can quickly judge which tactics are actually appropriate and effective for saving the planet (and for many specific kinds of social and ecological justice activism). A taxonomy of action can also suggest tactics we might otherwise overlook.

Broadly speaking, we can divide all of our tactics and projects either into acts of omission or acts of commission. Of course, sometimes these categories overlap. A protest can be a means to lobby a government, a way of raising public awareness, a targeted tactic of economic disruption, or all three, depending on the intent and organization. And sometimes one tactic can support another; an act of omission like a labor strike is much more likely to be effective when combined with propagandizing and protest.

In a moment we’ll do a quick tour of our taxonomic options for resistance. But first, a warning. Learning the lessons of history will offer us many gifts, but these gifts aren’t free. They come with a burden. Yes, the stories of those who fight back are full of courage, brilliance, and drama. And yes, we can find insight and inspiration in both their triumphs and their tragedies. But the burden of history is this: there is no easy way out.

In Star Trek, every problem can be solved in the final scene by reversing the polarity of the deflector array. But that isn’t reality, and that isn’t our future. Every resistance victory has been won by blood and tears, with anguish and sacrifice. Our burden is the knowledge that there are only so many ways to resist, that these ways have already been invented, and they all involve profound and dangerous struggle. When resisters win, it is because they fight harder than they thought possible.

And this is the second part of our burden. Once we learn the stories of those who fight back—once we really learn them, once we cry over them, once we inscribe them in our hearts, once we carry them in our bodies like a war veteran carries aching shrapnel—we have no choice but to fight back ourselves. Only by doing that can we hope to live up to their example. People have fought back under the most adverse and awful conditions imaginable; those people are our kin in the struggle for justice and for a livable future. And we find those people—our courageous kin—not just in history, but now. We find them among not just humans, but all those who fight back.

We must fight back because if we don’t we will die. This is certainly true in the physical sense, but it is also true on another level. Once you really know the self-sacrifice and tirelessness and bravery that our kin have shown in the darkest times, you must either act or die as a person. We must fight back not only to win, but to show that we are both alive and worthy of that life.

Acts of Omission

The word strike comes from eighteenth-century English sailors, who struck (removed) their ship’s sails and refused to go to sea, but the concept of a workers’ strike dates back to ancient Egypt.3 It became a popular tactic during the industrial revolution, parallel to the rise of labor unions and the proliferation of crowded and dangerous factories.

Historical strikes were not solely acts of omission. Capitalists went to great lengths to violently prevent or end strikes that cost them money, so they became more than pickets or marches; they were often pitched battles, with strikers on one side, police and hired goons on the other. This should be no surprise; any effective action against those in power will trigger a forceful, and likely violent, response. Hence, historical strikers often had a pragmatic attitude toward the use of violence. Even if opposed to violence, historical strikers planned to defend themselves out of necessity.

The May 1968 student protests and general strike in France—which rallied ten million people, two-thirds of the French workforce—forced the government to dissolve and call elections, (as well as triggering extensive police brutality). The 1980 Gdańsk Shipyard strike in Poland sparked a series of strikes across the country and contributed to the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe; strike leader Lech Wałęsa won the Nobel Peace Prize and was later elected president of Poland. General strikes were common in Spain in the early twentieth century, especially in the years leading up to the civil war and anarchist revolution.

Boycotts and embargoes have been crucial in many struggles: from boycotts of slave-produced goods in the US, to civil rights struggles and the Montgomery bus boycott in the name of civil rights, to the antiapartheid boycotts; to company-specific boycotts of Nestlé, Ford, or Philip Morris.

The practice of boycotting predates the name it itself. Captain Charles Boycott was the agent of an absentee landlord in Ireland in 1880. Captain Boycott evicted tenants who had demanded rent reductions, so the community fought back by socially and economically isolating him. People refused to work for him, sell things to him, or trade with him—the postman even refused to deliver his mail. The British government was forced to bring in fifty outside workers to undertake the harvest, and protected the workers with one thousand police. This show of force meant that it cost over £10,000 to harvest £350 of potatoes. Boycott fled to England, and his name entered the lexicon.

As we have discussed, consumer spending is a small lever for resistance movements, since most spending is done by corporations, governments, and other institutions. If we ignore the obligatory food, housing, and health care, Americans spend around $2.7 trillion dollars per year on their clothing, insurance, transportation, and other expenses. Government spending might be $4.4 trillion, with corporations spending $1 trillion on marketing alone. Discretionary consumer spending is small, and even if a boycott were effective against a corporation, the state would bail out that corporation with tax money, as they’ve made clear.

But there’s no question that boycotts can be very effective in specific situations. The original example of Captain Boycott shows some conditions that lead to successful action: the participation of an entire community, the use of additional force beyond economic measures, and the context of a geographically limited social and economic realm. Such actions helped lead to what Irish labor agitator and politician Michael Davitt called “the fall of feudalism in Ireland.”7

Of course there are exceptional circumstances. When the winter’s load of chicken feed arrived on the farm today, the mayor was driving the delivery truck, nosing carefully through a herd of curious cattle. But most people don’t take deliveries from their elected officials, and—with apologies to Mayor Jim—the mayors of tiny islands don’t wield much power on a global scale.

Indeed, corporate globalization has wrought a much different situation than the old rural arrangement. There is no single community that can be unified to offer a solid front of resistance. When corporations encounter trouble from labor or simply want to pay lower wages, they move their operations elsewhere. And those in power are so segregated from the rest of us socially, economically, culturally, and physically that enforcing social shaming or shunning is almost impossible.

Even if we want to be optimistic and say that a large number of people could decide to engage in a boycott of the biggest ten corporations, it’s completely reasonable to expect that if a boycott seriously threatened the interests of those in power, they would simply make the boycott illegal.

In fact, the United States already has several antiboycott laws on the books, dating from the 1970s. The US Bureau of Industry and Security’s Office of Antiboycott Compliance explains that these laws were meant “to encourage, and in specified cases, require US firms to refuse to participate in foreign boycotts that the United States does not sanction.” The laws prohibit businesses from participating in boycotts, and from sharing information which can aid boycotters. In addition, inquiries must be reported to the government. For example, the Kansas City Star reports that a company based in Kansas City was fined $6,000 for answering a customer’s question about whether their product contained materials made in Israel (which it did not) and for failing to report that inquiry to the Bureau of Industry and Security.8 American law allows the bureau to fine businesses “up to $50,000, or five times the value” of the products in question. The laws don’t just apply to corporations, but are intended “to counteract the participation of US citizens” in boycotts and embargoes “which run counter to US policy.”

Certainly, large numbers of committed people can use boycotts to exert major pressure on governments or corporations that can result in policy changes. But boycotts alone are unlikely to result in major structural overhauls to capitalism or civilization at large, and will certainly not result in their overthrow.

Like the strike and the boycott, tax refusal has a long history. Rebellions have erupted and wars have been waged over taxes; from the British colonial “hut taxes” to the Boston Tea Party. Even if taxation is not the cause of a war, tax refusal is likely to play a part, either as a way of resisting unjust wars (as the Quakers have historically done) or as part of a revolutionary struggle (as in a German revolution in which Karl Marx proclaimed, “Refusal to pay taxes is the primary duty of the citizen!”).

The success of tax refusal is usually low, partly because people already try to avoid taxes for nonpolitical reasons. In the US, 41 percent of adults do not pay federal income tax to begin with, so it’s reasonable to conclude that the government could absorb (or compensate for) even high levels of tax refusal.

Even though tax refusal will not bring down civilization, there are times when it could be especially decisive. Regional or local governments on the verge of bankruptcy may be forced to close prisons or stop funding new infrastructure in order to save costs, and organized tax resistance could help drive such trends while diverting money to grassroots social or ecological programs.

Through conscientious objection people refuse to engage in military service, or, in some cases, accept only noncombatant roles in the military. Occasionally these are people who are already in the military who have had a change of heart.

Although conscientious objection has certainly saved people from having to kill, it doesn’t always save people from dying or the risk of death, since the punishments or alternative jobs like mining or bomb disposal are also inherently dangerous. It’s unlikely that conscientious objection has ever ended a war or even caused significant troop shortages. Governments short of troops usually enact or increase conscription to fill out the ranks. Where alternative service programs have existed, the conscientious objectors have usually done traditional masculine work, like farming and logging, thus freeing up other men to go to war. Conscientious objection alone is unlikely to be an effective form of resistance against war or governments.