by DGR News Service | Sep 6, 2014 | Agriculture, Education, Lobbying

By Norris Thomlinson / Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i

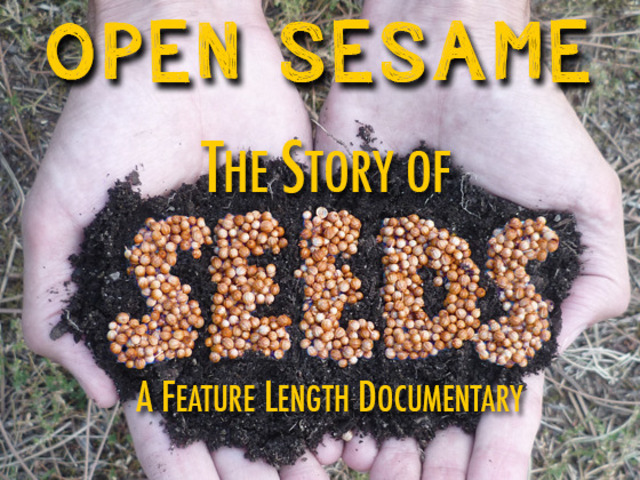

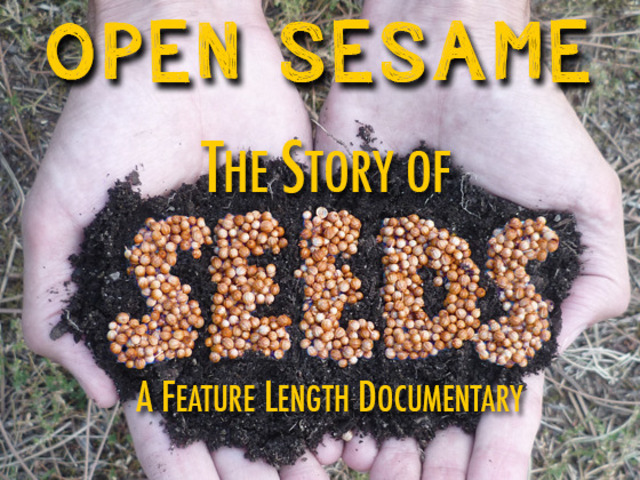

Open Sesame examines the importance of seeds to humans as the genesis of nearly all our domesticated foods. It details the tremendous loss in varietal diversity of our crops over the last century, due in large part to increasing corporate control over the seed market.

Farmers and gardeners in every region once had access to dozens of varieties of each vegetable and staple crop, finely adapted to the specific growing season, temperatures, rainfall patterns, insects, diseases, and soils of their area. With few people now saving their own seed, we’ve entrusted our food supply to a handful of seed companies selling the same handful of varieties to growers across the US. This will prove increasingly problematic as climate chaos increases divergence from climatic norms. We need a return to seed saving and breeding of numerous local varieties, each starting from a baseline adaptation to the specific conditions of each area. Diversity gives a better chance of avoiding complete catastrophic crop failure; this variety may yield in the heavy rains of one year, while that variety may succeed in the drought of the next.

The film shows beautiful time lapse sequences of seeds sprouting and shooting into new life. Even rarer, it shows people feeling very emotional about seeds, displaying extra-human connections we normally only see with domesticated pets, and hinting at the human responsibility of respectful relationship with all beings described by so many indigenous people. The movie highlights great projects from seed schools and the Seed Broadcast truck educating people on why and how to save seed, to William Woys Weaver and others within Seed Savers Exchange doing the on-the-ground work of saving varieties from extinction, to Hudson Valley Seed Library trying to create a viable business as a local organic seed company.

Civilization and Agriculture

Unfortunately, Open Sesame has an extremely narrow focus. Though it rightly brings up the issue of staple crops, which many people ignore in their focus on vegetables, it trumpets our dependence on grains, even showing factory farmed cattle, pigs, and chickens in an uncritical light. This assumption that humans need annual crops reveals an ignorance of agriculture itself as a root cause of our converging environmental crises. Even before industrialism accelerated the destruction and oppression, civilization and its cities, fed by organic agriculture, was eroding soil, silting up waterways, turning forests into deserts, and instituting slavery and warfare. Though the diminished diversity within our food crops should indeed cause concern, the far greater biodiversity loss of mass species extinctions under organic agriculture should spark great alarm, if not outright panic.

In one scene, the documentary shows a nighttime urban view of industrial vehicles and electric lights, bringing to mind the planetary destruction enacted by the creation and operation of these technologies. Beneath the surface, this scene contains further social and imperialistic implications of packing humans into artificial and barren environments. The residents of this scene are fully reliant on imported food and other resources, often stolen directly, and all grown or mined from land stolen from its original human and non-human inhabitants. But the film goes on to point out, without any irony, that all civilizations began with humans planting seeds, as if the only problem we face now is that industrialization and corporate control applied to agriculture threaten the stability of otherwise beneficial systems.

In a similar disconnect, Open Sesame proclaims the wonders of gardening, farming, and “being in nature” while showing simplified ecosystem after simplified ecosystem ― annual gardens and fields with trees present only in the background, if at all. As any student of permaculture or of nature could tell you, the disturbed soil shown in these human constructions is antithetical to soil building, biodiversity, and sustainability. The film describes seeds “needing” our love and nurturing to grow, positioning us as stewards and playing dangerously into the dominating myth of human supremacism. Such dependence may (or may not) be true of many of our domesticated crops and animals, but I think it crucial to explicitly recognize that in indigenous cultures, humans are just one of many equal species living in mutual dependence.

Though the documentary chose not to tackle those big-picture issues, it still could have included perennial polycultures, groups of long-lived plants and animals living and interacting together in support of their community. For 99% of our existence, humans met our needs primarily from perennial polycultures, the only method proven to be sustainable. The film could have chosen from hundreds of modern examples of production of vegetables, fruit, and staple foods from perennial vegetable gardens, food forests, and grazing operations using rotating paddocks. Even simplified systems of orchards and nutteries would have shown some diversity in food production options. Besides being inherently more sustainable in building topsoil and creating habitat, such systems rely much less on seed companies and help subvert their control.

Liberal vs Radical

The Deep Green Resistance Youtube Channel has an excellent comparison of Liberal vs Radical ways of analyzing and addressing problems. In short, liberalism focuses on individual mindsets and changing individual attitudes, and thus prioritizes education for achieving social change. Radicalism recognizes that some classes wield more power than others and directly benefit from the oppressions and problems of civilization. Radicalism holds these are not “mistakes” out of which people can be educated; we need to confront and dismantle systems of power, and redistribute that power. Both approaches are necessary: we need to stop the ability of the powerful to destroy the planet, and simultaneously to repair and rebuild local systems. But as a radical environmentalist, I found the exclusively liberal focus of Open Sesame disappointing. There’s nothing inherently wrong with its take on seed sovereignty; the film is good for what it is; and I’m in no way criticizing the interviewees doing such great and important work around seed saving and education. But there are already so many liberal analyses and proposed solutions in the environmental realm that this film’s treatment doesn’t really add anything new to the discussion.

A huge challenge I have with liberal environmentalism is its leap of logic in getting from here (a world in crisis) to there (a truly sustainable planet, with more topsoil and biodiversity every year than the year before.) Open Sesame is no exception: it has interview after interview of individuals carrying out individual actions: valuable, but necessarily limited. Gary Nabham speaks with relief on a few crop varieties saved from extinction by heroic individual effort, but no reflection is made on the reality of how much we’ve lost and the inadequacy of this individualist response. We see scene after scene of education efforts, especially of children. We’re left with a vague hope that more and more people will save their own seed, eventually leading to a majority reclaiming control over their plantings while the powerful agribusiness corporations just fade away. This ignores the institutional blocks deliberately put in place precisely by those powerful companies.

The only direct confrontation shown is a defensive lawsuit begging that Monsanto not be allowed to sue farmers whose crops are contaminated by patented GMOs from nearby fields. The lawsuit isn’t even successful, and the defeated farmers and activists are shown weary and dejected, but with a fuzzy determination that they can win justice if they keep trying hard enough. The film could instead have built on this example of the institutionalized power we’re up against and explored more radical approaches to force change. Still within the legal realm, CELDF (Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund) helps communities draft and pass ordinances banning things like factory farming, removing corporate personhood, and giving legal rights to nature within a municipality or county. Under such an ordinance, humans could initiate a lawsuit against agricultural operations leaching chemicals and sediment, on behalf of an impacted river. This radical redistribution of decision making directly confronts those in power and denies them the right to use it against the community and the land.

In the non-legal realm, underground direct attacks and aboveground nonviolent civil disobedience have successfully set back operations when people have cut down GMO papayas, burned GMO sugar beets, and sabotaged multiple fields and vineyards. The ultimate effectiveness of these attacks deserves a whole discussion in and of itself, but they would have been worth mentioning as one possible tactic for ending agribusiness domination of our food supplies.

In a perfect demonstration of the magical thinking that wanting something badly enough will make it happen, the documentary concludes with a succession of people chanting “Open sesame!” We’ve had 50 years of experience with this sort of environmentalism, long enough to know it’s not working. We also know that we, and the planet, have no time left to waste. We need to be strategic and smart in our opposition to perpetrators of destruction and in our healing of the damage already done. The Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy of Deep Green Resistance offers a possible plan for success, incorporating all kinds of people with all kinds of skills in all kinds of roles. If you care about the world and want to change where we’re headed, please read it, reflect on it, and get involved in whatever way makes the most sense for you.

by DGR News Service | Mar 30, 2014 | Male Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

By Kourtney Mitchell / Deep Green Resistance

On June 28, 1964, Malcolm X gave a speech at the Founding Rally of the Organization for Afro-American Unity (OAAU) at the Audubon Ballroom in New York. In the speech, he stated what became his most famous quote:

We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.

Interestingly, X was popularizing a line from a play titled Dirty Hands by the French intellectual Jean-Paul Sartre, which debuted in 1948:

I was not the one to invent lies: they were created in a society divided by class and each of us inherited lies when we were born. It is not by refusing to lie that we will abolish lies: it is by eradicating class by any means necessary.

There are some really important ideas presented in both of these quotes. Sartre succinctly summarized the primary struggle for the socially conscious – that society as we know it is divided into classes, and that social change is not achieved merely by refusing to behave like dominant classes, but by ultimately dismantling the power structures upholding this stratification.

X’s spin on this was equally profound. The white power structure of his time enacted brutal and morally reprehensible repression on the masses of black people in the United States, and X was stating the very real yet existential condition: that this repression was a dehumanizing tactic, upheld by violence and enslavement, and that the response to this repression must equal the scope of the problem. Simply put, white supremacism will use any and all means necessary to maintain power, and thus those fighting against it must do the same.

The modern environmental and social justice movement could learn a thing or two from these quotes. Any one who is not meditating in a cave should realize by now that this culture we live in – industrial civilization – is quickly killing the planet. All life support systems on Earth are declining, and have been doing so for several decades. As a matter of fact, since the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, generally considered the birth of the modern environmental movement, there has not been a single peer-reviewed article contradicting that statement.

This should ring some alarms for everyone, but surely for those in the movement, right? One would think so, but unfortunately this does not seem to be the case. Instead, what we are seeing is a continued ignorance of the true scale of environmental destruction, and a refusal to be honest about what it will take to stop it. What we are seeing is a constant faith on popular protest and nonviolence as the end goal of resistance, a hegemonic adherence to pacifism.

At the same time that nearly all native prairies are disappearing, and insect populations are collapsing, and the oceans are being vacuumed, and nearly two hundred species of animals are going extinct every single day, women are also being raped at a rate of one every two minutes. A black male is killed by police or other vigilantes at a rate of one every 28 hours. There are more slaves today than at any time during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. And indigenous cultures and languages are being wiped off the planet.

It is apparently certain that for all of our good intentions – our feelings of loving-kindness, taking the moral high ground and being the change we wish to see in the world – we are failing, and miserably. We are losing.

This must change.

It is time to face the truth, a truth climate scientists, indigenous warriors and anyone who is half awake have been telling us for a really long time – our planet is being killed, and we must fight back to end the destruction before all life on the planet perishes for good.

A starting point for establishing an effective response to environmental destruction and social oppression is to develop a clear understanding of the mechanisms for this arrangement. The dominant classes of people who are enacting this brutality utilize concrete systems of power to do so, namely industrial capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy and human supremacism.

These institutions of power are run by people – human beings, who instead of holding a reverence for life and love of freedom, value privilege and power above all else. This system is based upon, and would quickly collapse without, widespread and pervasive violence. Privilege is upheld by violence, because no one willingly cedes their freedom and autonomy unless forced to do so.

There is a necessary realization one must have when considering all of this, and it is a realization many in the so-called movement are yet to have: as the oppression of human and non-human communities and the destruction of the planet is being enacted by a particular class of people – that is, a group of people sharing a real or perceived identity and having similar goals and the means to achieve those goals – it is also being endured by a particular class of people.

Men, as a class of people whose collective behavior has a very real effect, are oppressing women as a class. This is not to claim that every single man on the planet has some palpable sense of hating women, but it does mean that to be a man in this society is to behave in a socialized manner that oppresses women.

Whites as a class of people are oppressing people of color. This is not to say that every single white-identified person on the planet has some palpable sense of hating people of color, but that to be white in this society is to behave in a manner that oppresses people of color in at least some ways.

If the violence is enacted by classes, the resistance must also exist on the class-level. It has never been enough for the individual to make personal, lifestyle changes so that they can feel better about themselves while the rest of the people in their class suffer. Systems of oppression are not defeated by individuals – they are defeated by organizing with others, a collective struggle.

This is what it means to be radical. As radicals, we aim to get to the root of the problem. Radical anti-racists understand that the white identity is based upon privilege, and that privilege is inherently oppressive to people of color. Radical anti-sexists understand that the concept of gender is built upon male dominance and female submission, which is inherently oppressive to women. And radical environmentalists understand that industrial civilization – based upon extraction, destructive agricultural practices and the genocide of indigenous cultures – is killing the planet.

From there, we draw the line. A radical’s primary goal is not to combat the symptoms of oppression – we do not merely wish to navigate the gender spectrum, toying with it at will as some kind of protest. We wish to abolish gender, recognizing it as the primary basis for women’s oppression. And we do not wish to merely give people of color a bigger slice of the pie in the white supremacist power structure. We wish to abolish white supremacy altogether, and furthermore to overcome the concept of race itself. Radical environmentalists cannot afford to continue to espouse technological fixes for a problem caused by technology and extraction. No, industrial civilization is wholly irredeemable, and no amount of technology can fix it.

What should be apparent is that our movement needs more than nonviolence and good feelings. We need to mount a serious threat to the power structures, one that is forceful and continuous. We need militant action. Those killing the planet will not stop unless forced to do so.

Nonviolence is a powerful tactic when correctly applied, but it alone cannot match the scale of destruction. When coupled with strategic attacks on the infrastructure of oppression, it can result in concrete, lasting change.

And this is the strategy of Deep Green Resistance. As an aboveground movement, we use nonviolent direct action, putting our bodies between life and those who wish to destroy it. Though we have no connection to (and no desire to have a connection with) any underground that may exist, we actively support the formation of an underground, encouraging militant resistance that will bring down oppressive institutions for good.

DGR is also dedicated to the work of helping to rebuild or to build new, sustainable human communities. We are working towards a culture of resistance – where oppression and ecocide are not tolerated, and where people incorporate resistance into their everyday lives. We work to establish solidarity and genuine alliance with oppressed communities, always keeping an eye towards justice, liberating our hearts and minds from the hegemonic tendencies of privileged classes. DGR understands that marginalized communities have been on the front lines of resistance from the very beginning, defending their way of life and reclaiming their autonomy. For too long, pacifists and dogmatic nonviolent activists have left the hard work of actual resistance to those marginalized groups, shying away from the real fight. No more – it is now time for men to combat sexism, for whites to combat racism, and for the civilized of this culture to fight against industrial empire and bring it down.

This analysis and this strategy should be inspiring. But what is more inspiring is that we have the means to achieve our goals. We know how to bring down industrial capitalism, which is controlled by critical nodes of technology and extraction. When these nodes are attacked and brought down in a way preventing their rebuilding, the system begins to collapse. The mechanisms of control – the military, the police and the media – cannot operate without consistent input of fossil fuels and willing agents.

When this system falls, the living world will rejoice. Two hundred species of animals who would have gone extinct will instead live and flourish. Indigenous communities will reclaim their traditional homelands. The salmon will begin to spawn anew with each dam taken down, and the rivers will rush with life.

This is the world for which we fight. And we intend to win.

Let’s Get Free! is a column by Kourtney Mitchell, a writer and activist from Georgia, primarily focusing on anti-oppression and building genuine alliance with oppressed communities. Contact him at kourtney.mitchell@gmail.com.

by DGR News Service | Mar 24, 2014 | Gender, Women & Radical Feminism

By Rachel / Deep Green Resistance Eugene

The following is a response to an open letter written by Bonnie Mann to Lierre Keith.

Hello Professor Mann,

You wrote an open letter recently to my friend and fellow activist Lierre Keith. You don’t know me, and I don’t know you, but as your letter discusses issues which are very important to me, and as I feel that you’ve gravely misconstrued those issues, it feels incumbent upon me to respond. You may choose to write me off as “uncritical,” since I share the views that you have dismissed as such in your letter, but I hope that you will instead choose to listen and reflect on my reasons for finding your letter uncritical at best, and in all truth, irresponsibly misleading at worst. At the risk of casting too wide a net, there are two things I’d like to address: the things you say in your letter, and the things you don’t say in your letter.

You write that you don’t support those who tried (and failed) to get Lierre’s invitation to speak rescinded, because “you don’t get ‘safe space’ in the public sense from not being subjected to attacks, or to the presence of those by whom you consider yourself to have been attacked.” You don’t specify whether by attacks you are referring to political disagreement, or the kind of rape and death threats, stalking, sexual harassment, and occasional physical assault to which I and other radical feminists are regularly subject. This ambiguity, which pervades your letter’s arguments, works to stymie direct discussion of the issues. If by “attacks” you mean “political disagreement,” then I agree. Contrary to the beliefs of many who try to blacklist radical feminist thought from the public sphere, I do not believe that mere disagreement is equivalent to physical violence.

You go on to say: “I think you get safe space, or as safe as space gets, from having your community stand by you in the face of attacks.” If that’s true, then “as safe as safe space gets” feels pretty damn unsafe when you dare to question the inevitability or the justice of gender. I and the radical feminists I know have formed a community that supports each other in the face of attacks. Unfortunately, supporting each other has not stopped the bullying, the rape and death threats, the intimidation and the stalking and the harassment. This is as safe as space gets for radical feminists who stick to their convictions instead of abandoning them. It’s disturbing to me that nowhere in your letter do you even acknowledge the reality of what we deal with every time we open our mouths to disagree with the currently popular ideology around gender.

You mention having watched a presentation of mine on gender that I wrote about a year ago, entitled “The End of Gender” (or alternatively “I Was a Teenage Liberal”), so I won’t waste time on details of my past that you, presumably, are already familiar with. Suffice it to say that my views on gender have taken the opposite trajectory from yours. One of the most easily challengeable and, frankly, one of the cheapest ways that you dismiss Lierre’s politics in your letter is by suggesting that they are less valuable because they are so old as to be archaic or outmoded. You imply this by describing how reading her arguments brings you “back in time,” and by mentioning several times that you also heard those same arguments from her thirty two years ago. That argument might seem slightly more viable if Lierre, or others in her and your generation, were the only ones who hold similar convictions today.

My very existence (much less my work as an activist) renders that line of criticism less-than-viable. You wrote that you last spoke to Lierre in 1989, but I was born in 1989, and women closer to my age are some of the most vocal and active gender-critical feminists I know. Some of us, the lucky ones, benefit from the support and guidance of women who have been feminists since before we were born. Others came to radicalism because they could see that the ideology we’ve been fed by academia and the dominant culture – individualist, neoliberal “feminism” – is actively working against the advancement of women’s human rights. Young women organize radical feminist conferences, write gender-critical analysis, fight to maintain the right of females to organize as a class, and support each other through the intimidation, threats, and ostracization that such work earns us. We do not appreciate being ignored by those who would take the easy way out in dismissing our politics.

You write that the ideology of gender that gave rise to today’s trans ideology and practice was “brand new” to you at the time you first encountered it, and that it “freaked you out” because it “didn’t match the analysis” that you held at the time, which you equate to the analysis that Lierre and I and so many others hold today. Your implication, and the dismissal it contains, is clear – radical feminist disagreement with liberal gender ideology stems from cognitive dissonance and unease toward unfamiliar ideas, not from reasoned analysis. You imply that radical feminism is an artifact from an earlier time, and that the only women who still cling to it do so because they are afraid of new ideas. Again, you write as if women of your and Lierre’s generation who share your early experience of feminism are the only radical feminists who still walk the Earth.

This argument falls completely flat for me and so many radical feminists of my generation. Liberal gender ideology has never been “brand new” for us. It is not unfamiliar to us; we grew up swimming in it. We’re not clinging to relics, we’re reaching for a politics that actually addresses the scope of the problems. It was gender-apologism that began to give us cognitive dissonance, after our experiences brought us to some uncomfortable and challenging conclusions: Female people are a distinct social class, and its members experience specific modes of oppression based on the fact that we’re female. All oppressed classes have the right to organize autonomously and define the boundaries of their own space. Gender is socially constructed; there are no modes of behavior necessarily associated with biological sex. The norms of gender function to facilitate the extraction of resources from female bodies. The extraction of resources from female bodies forms the foundation of male supremacy, and thusly, male supremacy fundamentally depends on the maintenance of gender.

Like many of radical feminism’s detractors, you have chosen to focus your response to our politics on one statement, perceived belief, or piece of writing, which is taken as a representation of us as a group in order to make it easier to misconstrue and dismiss our views. This is called scapegoating, and Lierre’s email is an oft-selected target for it. I understand that your letter was addressed to Lierre, and so it makes sense that you would focus on her stated views. However, there are multiple other more recent and detailed pieces of writing from her on the subject that you chose to ignore. Maybe the choice to exclude these was “a symptom of not listening.” Maybe it “marks a distaste for complexity, ambiguity, nuance.” I don’t pretend to know, but it was clearly a choice that allowed you to sidestep direct engagement with the basic principles and broader conclusions of radical feminist politics.

In describing your views before you adopted your current ideology around gender, you write that “we weren’t afraid of the people so much as we were afraid of the phenomenon. Why? Because if gender is a sex-class system, and that’s all it is, there is no way to explain the existence of trans women at all. That’s like white people trying to get into the slavery of the 1840s. If gender is a sex-class system, and that’s all it is, then the only “trans” should be female to male, because everybody should be trying to get out and nobody should be trying to get in – yet it’s the transition from male to female that is cited as troubling.”

First of all, if you had bothered to take a broader and more accurate view of Lierre’s gender politics and her writing on the subject, you’d have found that she does not only cite the transition from male to female as troubling. She cites the entire system of enforced stereotypes called gender as troubling, including the trans ideology that justifies enforcing the categorization of qualities and behavior, and presents cutting up people’s bodies to fit those enforced stereotypes as a solution. I do appreciate that you actually engage with some of her arguments, since most who choose to scapegoat her usually skip directly to threats and insults. However, your analysis of the two analogies you chose to address leave some things to be desired. You begin with:

“I am a rich person stuck in a poor person’s body. I’ve always enjoyed champagne rather than beer, and always knew I belonged in first class not economy, and it just feels right when people wait on me.”

This is only a reverse analogy, as you call it, if you believe that she is only intending to address the phenomenon of male people identifying themselves as female. You’re correct that this example, when applied to gender, is analogous to a female person identifying themselves as male. I do not believe that this fact lessens its illustrative power. If this “rich person stuck in a poor person’s body” tried to “transition” to higher economic status based on their inner identification with wealth, how do you think they’d be treated by actual rich people? Might the treatment of this person mirror, say, the treatment of a trans man trying to join a group of men’s rights activists (MRAs)? Here’s a better question: Even if this person was able to “pass” as wealthy by appearing and acting to be so, would their passing have any affect at all on the capitalist structures of power that keeps them in poverty in the first place? Would passing as wealthy in appearance help them acquire actual financial power? Would it retroactively grant them a silver spoon at birth and a BMW on their sixteenth birthday?

You reverse the analogy (“I’m rich, but I’ve always identified as poor, so I divest myself of my wealth and go join the working class”) and say that it’s less powerful that way. I disagree. I think that the reversed version is extremely illustrative of the flaws in your argument, and in liberal thinking more generally. You write:

“Who wouldn’t welcome you, if you really divested yourself of your wealth and joined marches in the street to increase the minimum wage?”

Do you really think that someone can divest themselves not only of their material wealth, but of their history as a wealthy person? I don’t know about you, but if a rich person voluntarily gave up their wealth and said to me “Hey fellow member of the working class! I’m just like you, and there is no difference between our experiences of the world,” I’d tell them to fuck off. Becoming penniless now is not equivalent to going hungry as a kid, struggling to afford education throughout your life, watching your parents pour their lives into multiple underpaid jobs, or having to decide between rent and medical bills. It’s insulting to suggest that someone can shrug off years of privilege and entitlement and safety at will. In large part, growing up with privilege is the privilege. The punishment meted out to males who disobey the dictums of masculinity (a punishment that is yet another negative effect of the sex caste system) can be severe, and of course it’s indefensible. However, it is distinct from the systematic exploitation that females experience because we are female.

You go on to the second analogy: “I am really native American. How do I know? I’ve always felt a special connection to animals, and started building tee pees in the backyard as soon as I was old enough. I insisted on wearing moccassins to school even though the other kids made fun of me and my parents punished me for it. I read everything I could on native people, started going to sweat lodges and pow wows as soon as I was old enough, and I knew that was the real me. And if you bio-Indians don’t accept us trans-Indians, then you are just as genocidal and oppressive as the Europeans.”

You respond: “Maybe we thought gender was a ‘a class condition created by a brutal arrangement of power,’ and only that, but we would never have made the same claim about being native American. Why? It’s blatently reductive. It’s reducing a rich set of histories, cultures, languages, religions, and practices to the effect of a brutal arrangement of power – which is of course a very important part of it. But “being native American” is not merely an effect of power, in the way we thought gender was.”

Your objections to these analogies consistently prove the points that you’re trying to challenge. Of course gender cannot be parallel to “being native American” in this or any other analogy. Gender is parallel to colonial ideology in this analogy. More specifically, male supremacy is parallel to the colonialial power relation in this analogy, and gender is parallel with the stereotypes that colonialism imposes onto the colonized. The “drunk Indian” stereotype, or the image of the “savage,” only have anything to do with “being native American” because the ideology and practice of white supremacy was and continues to be imposed by Europeans on an entire continent’s peoples in order to exploit them. The female stereotypes we call “femininity” (domestic laborer, mother, infantalized sex object) only have anything to do with being female because the ideology (gender) and practice (patriarchy) of male supremacy was and is imposed by males onto females in order to exploit them. Of course it’s reductive to condense an entire distinct, specific set of experiences, the good and bad and everything in between, into a brutal arrangement of power – and this is exactly what gender does.

Gender takes the lived experiences of being female or being male and reduces those experience to sets of stereotypes. Transgender ideology retains those same oppressive stereotypes, but liberalizes their application by asserting that anyone can embody either set of stereotypes, regardless of their biological sex. This does not take away the destructiveness and reductiveness of the stereotypes, and in fact it reinforces them. The existence of outlaws requires the law, and maintaining an identity as a “gender outlaw” requires that the law – the sex castes – be in full effect for the rest of us. If “twisting free” of gender and the power relations of male supremacy is possible for a few of us, doesn’t that mean that those of us who fail to twist free are choosing the oppression we experience under gender? Perhaps we’re not trying hard enough to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps. How about other oppressive power arrangements – do the colonized, the racially subjugated, or those in poverty ever get to “twist free” of the power relations they live within? Do racial stereotypes, for instance, “take on a life of their own in the imaginary domain”? To defend gender as even occasionally being estranged from the machinations of power is to defend male supremacy, and to argue that any aspect of society can be apolitical is to completely ignore the ways that hegemony actually functions.

The only other groups of people who have argued to me that gender stereotypes are natural, biological, or apolitical, aside from gender-apologists, are fundamentalist christians and MRA’s. Forgive me if I don’t see how this is remotely progressive. This represents an adjustment in the rhetoric of patriarchy – not resistance to it. These stereotypes are not arbitrary; just like the stereotype of the Indian “savage,” or of the lazy (brown) immigrant, or of the freeloading (brown) “welfare queen,” the stereotypes called gender function to facilitate the extraction of resources. In the case of the “savage” Indian stereotype, the resource in question was and still is land. In the case of women, the resources are labor, reproduction, and sex, and the stereotypes (housewife, mother, infantalized sex object) come to match. It’s not an accident that these stereotypes correspond with the resources that women are exploited for. This is the purpose of gender. What does it mean that those in the academy almost universally embrace the idea that these regressive stereotypes must be reformed, justified, normalized, fetishized, idealized, and extended – but never challenged at their root?

I think you’re right that misogyny is not the conscious reasoning of every male person who begins identifying themselves as female. When I was a high school teacher, I had male students who were told by counselors that they were sick with “gender dysphoria” and put on hormones by doctors because they failed to live up to masculine stereotypes. These boys aren’t consciously out to invade female space – but they, and the abuse that they receive at the hands of the medical and psychiatric establishments, certainly aren’t poster children for why gender castes deserve to be rationalized or maintained. The fact that some males have a negative experience of gender does not erase the fact that structurally, on the macro level, gender exists to facilitate the extraction of resources from female bodies. Gender is the chain, and male supremacy is the ball. Just because males sometimes trip over that chain does not erase the fact that the ankle it’s cuffed to is always female.

I think you’re right that when you say that we “negotiate and take up and resist and contest or affirm these structures in profoundly complex ways and sometimes deeply individual, creative, and unique ways,” but it sounds like you’re using the fact that individuals have varied experiences to dismiss or minimize the reality of the larger structures that those experiences occur within. Individual experiences may not always match up with the larger structures of exploitation, but this does not mean that those larger structures become irrelevant. I also think you’re right that each of us “seeks a way of living, a way of having the world that is bearable.” But this does not erase the fact that gender, the stereotypes that it is composed of, and the exploitation it facilitates, compose one of the oppressive systems preventing us from finding a bearable, much less a safe or just, way of having the world.

You end your letter by, yet again, expressing a patronizing disapproval that Lierre has held the same convictions for thirty two years. I agree that we should constantly be seeking new information, new perspectives, and actively incorporating them into our politics. However, holding consistent core convictions isn’t always an indication of stagnation or dogmatism – sometimes it’s called “having principles.” Would you use this argument against others who stick to their political guns in the face of backlash and opposition? Indigenous communities that have fought for sovereignty for centuries? The women who struggled through the generations for suffrage?

Putting radical feminist principles (like the right of females to organize autonomously) into practice comes with a cost. I and others have come to accept that cost after challenging, painful analysis of radical feminism’s merits. You dismiss Lierre’s radical feminism as an “uncritical” relic from a simpler time, but for me and others in my position, radical feminism has been a lifeline of critical thought. We grew up within a “feminism” that uncritically accepted the inevitability and the naturalness of gender, the neoliberal primacy of individualism, and ultimately, the unchallengeability of male supremacy. You characterize those who hold firm to feminist political convictions as fetishizing clean lines, simplicity, and the safety of familiarity. I’m here to tell you that my worldview was a lot simpler and more familiar back when I believed that gender stereotypes were voluntary, natural, defensible, inevitable, even holy. My life was a lot simpler and safer when I was content to keep quiet and continue parroting liberal nonsense. You’re right that individual experiences of gender differ, and you’re right that the situation is complicated, but complexity does not have to derail the fight against male supremacy on behalf of women as a class – at least, it doesn’t have to for all of us.

-Rachel

by DGR News Service | Feb 13, 2014 | Building Alternatives

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

Without gods or masters, how do we live? Who do we live for?

One of my earliest acts of rebellion was leaving behind the religion of my parents. There was no legitimate authority in my eyes; neither natural nor supernatural.

Religion seemed an obvious enemy: clearly corrupt, notoriously pacifying, and easy to vilify. In well-meaning haste, I cast religion as something stark: always monotheistic, always Christian. And further: always dogmatic, always a tool of the powerful.

Reality is so inconveniently complex. I wanted to believe that I could live by the radical slogan, “no gods, no masters,” and truly be free of both. I wanted to believe that it is even possible to live without serving something larger than myself, on the ground and in the cosmos, in spirit and flesh.

The dominant culture forces upon us gods and masters in their most destructive forms. But in rejecting them, which other gods and masters do we end up serving? Who do we live our lives for? Which stories do we live by? And how?

Writes Rob Bell:

The danger is that in reaction to the abuses and distortions of an idea, we’ll reject it completely. And in the process miss out on the good of it, the worth of it, the truth of it.

All religions ask us to ask ourselves one question: “How shall I live my life?” For the socially-conscious, for the socially-active, this question is our guiding beacon. It always has been.

The journey towards that beacon, the attempt to describe what it means to be human, routinely leads political people to religion. It certainly led me.

I’ll be candid: I go to church. About a year ago, I could no longer deny the yearning inside me to have a spiritual home for my activism; some kind of sanctuary to rest and recharge.

The church I found is a progressive one and part of the Unitarian Universalist tradition. At first, I was skeptical. What would my radical comrades think? What did I even think? But sermon after sermon spoke to political struggle, past and present. Sermon after sermon spoke to living in reverence and humility and integrity. Then I read the official set of Unitarian Universalist principles, which includes “the inherent worth and dignity of every person”, “the goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all”, and “respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” Despite all apprehension, I knew I was being stimulated and challenged. I knew I was growing.

Spiritual practice is not a replacement for the hard work of political organizing, but a supplement to it; sometimes, a basis for it. In his book, Prophetic Encounters: Religion and the American Radical Tradition, Dan McKanan explains the relationship. He writes that not only have religion and radicalism always been intertwined, but that radicalism is in itself a form of religion. “It occupies much of the same psychological and sociological space,” writes McKanan. “People are drawn to religious communities and radical organizations in order to connect their daily routines to a more transcendent vision of heaven, salvation, or a new society.”

If religion starts with a capital “R”, if it has a singularly destructive form and purpose, if it is categorically opposed to liberation, how do we explain religions of resistance and religions of communion?

How do we explain former-slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who said it was only alongside other radicals that he could “get any glimpses of God anywhere”?

How do we explain Shawnee warrior Tecumseh, who tried to unite tribes under the “Great Spirit” for one of the largest resistance campaigns against white colonialism?

How do we explain Catholic anarchist Dorothy Day, who referred to the “poor and oppressed” as “collectively the new Messiah”?

How do we explain the countless radical movements throughout history which were firmly rooted in religion? How do we explain religions that have acted not as an “opiate of the masses”, but as a mobilizer of the masses?

How do we explain the thousands of indigenous human cultures able to live in place for essentially eternity, because they believed—and continue to believe—in the holiness of the natural world?

We needn’t fall in line with any of these specific religions to recognize the roles they have played in making our world a better place.

Religion can be many things, both righteous and rotten, but it certainly is not one, monolithic institution.

What is it then? “Religion, in reality, is living,” writes Native American scholar, Jack D. Forbes. “Our religion is not what we profess . . . our religion is what we do, what we desire, what we seek, what we dream about, what we fantasize, what we think. . . . One’s religion, then, is one’s life, not merely the ideal life but the life as it is actually lived.”

If religion is what we do, none of us can be said to be truly non-religious. We may be non-monotheistic. We may be non-Christian. We may be, and hopefully are, non-dogmatic and non-destructive.

All of us embody our religions each and every day. We may pick from already existing traditions or practices. We may create our own. But to assume it is even possible to live without religion is to live religiously in denial. Our actions, small and large, speak loud and clear of which religion we adhere to, of which gods and masters we ultimately serve.

Without religion, how do we live, who do we live for? If we don’t consciously choose, our actions choose for us. We can choose to be accountable to others, we can choose communion, we can choose to serve life. We can choose to live in such a way that, year after year, actually creates more ecological health and social justice. Or, we can pretend we are exempt from choosing. We can pretend to be non-religious or anti-religious, yet serve a certain religion, certain gods and masters, nonetheless. At its root, the word “worship” means “to give something worth.” In our daily lives, where do we see worth? What do we, through intention and action, give worth?

The dominant culture is deeply religious and ever eager to force its own religions upon us. Forbes writes that we all suffer under the wetiko, or cannibal, sickness: “Imperialism, colonialism, torture, enslavement, conquest, brutality, lying, cheating, secret police, greed, rape, terrorism.” The cannibal sickness is a religion. It is, as Forbes has termed it, “a cult of aggression and violence.”

Whether or not we like it, this is the cult we’ve been socialized into. Its values come naturally for us; unseating them from our hearts and minds is a lifetime project. But if we don’t try, these values will rule our lives. If we don’t replace the cannibal religion with our own religion—that is, if we don’t adopt and act from an opposite set of values—we inevitably act in its service, we inevitably worship it.

“A word for religion is never needed until a people no longer have it,” Forbes writes. “Religion is not a prayer, it is not a church, it is not theistic, it is not atheistic, it has little to do with what white people call ‘religion.’ It is our every act.”

Ailed by the cannibal sickness, how do we act? Forbes continues, “If we tromp on a bug, that is our religion; if we experiment on living animals, that is our religion; if we cheat at cards, that is our religion; if we dream of being famous, that is our religion; if we gossip maliciously, that is our religion; if we are rude and aggressive, that is our religion. All that we do, and are, is our religion.”

This is why I go to church: to share with and be held accountable by a congregation of people, all of us struggling to live out of a religion that serves not the cannibal sickness, but life. Sure, not everyone needs a congregation for this. But I find it invaluable.

In a sermon, one of the ministers at my church described his vision of religion. He said it is both private and public, an organization of people and a personal practice. He said it is an overarching myth, a path towards a new way of living. And finally, he said that the root of the word “religion” means “to bind,” because it is meant to bind each of us into a community, all working and walking together.

Another one of the ministers at my church put it this way:

If we are living, breathing, hurting, laughing, crying, questing human beings, it is impossible not to be spiritual beings. Spirituality is the energy that connects us to the greater pulse of life. We work on and with our spirituality, not to become divine, but to become more human.

Radical activism can be religious just as religion can be radical. Look around. Life moves. We can join that movement, or we can stand against it. We choose anew each and every day. Love life. Defend life. Make it your religion.

Ben Barker is a writer, activist, and farmer from West Bend, WI. He is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. Read other articles by Ben, or visit Ben’s website.

This piece was originally published at: http://dissidentvoice.org/2014/02/the-gods-of-a-radical/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 1, 2014 | Pornography

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

This essay was originally published in the Fall 2013 edition of Voice Male.

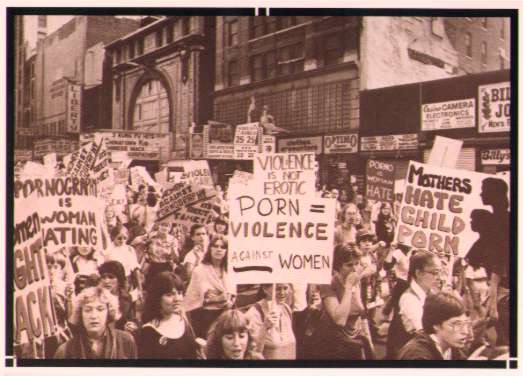

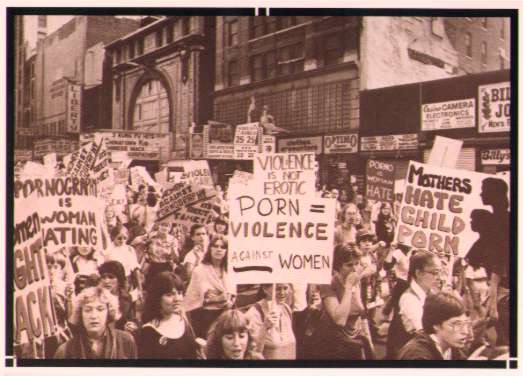

If the fight against pornography is a radical one, where are the radicals fighting against pornography?

Earlier this year, the 18th annual Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair, an event that brings together radical activists from around the world, was held at the headquarters and production facility of so-called “alternative” porn company, Kink.com.

Kink.com is known for its unique brand of torture porn. As Gail Dines reports, women are “stretched out on racks, hogtied, urine squirting in their mouths, and suspended from the ceiling while attached to electrodes, including ones inserted in their vaginas.” But to grasp the agenda of Kink.com, we can just go to the source: founder Peter Acworth started the company after devoting his life to “subjecting beautiful, willing women to strict bondage.”

When the Anarchist Bookfair announced its choice of venue, feminists were outraged. The few who were billed to speak during the event dropped out. But ultimately, the decision was defended, the outcry lashed back against, and the show went on.

Anarchists are my kind of people—or so I thought. When I first discovered the radical Left some eight years ago, I thought I’d stumbled on the revolution. The rhetoric seemed as much: brave, refreshing demands for human rights, equality, and liberation; a steadfast commitment to struggle against unjust power, however daunting the fight.

It wasn’t long, though, before my balloon of hope burst. To the detriment of my idealism and trust, the true colors of my radical heroes began to show.

Pornography was then and is now one such let down. Over the years, I’ve bounced between a diversity of groups on the radical Left: punks, Queers, anarchists, and many in between. But wherever I went, porn was the norm.

Here’s the latest in radical theory: “We’re seventeen and fucking in the public museum. I’m on my knees with your cock in my mouth, surrounded by Mayan art and tiger statues. Our hushed whispers and frenzied breathing becomes a secret language of power. And us, becoming monstrous, eating-whole restraint and apology. The world ruptures as we come, but it isn’t enough. We want it all, of course—to expropriate the public as a wild zone of becoming-orgy, and to destroy what stands in our way.” I’m sad to report that this quote, and the book it comes from, reflects one of the most increasingly popular of the radical subcultures.

Conflating perversion and revolution is nothing new. We can trace the trend all the way back to the 1700s in the time of the Marquis de Sade, one of the earliest creators and ideologues of pornography (not to mention pedophilia and sadomasochism).

Sade was famous for his graphic writings featuring rape, bestiality, and necrophilia. Andrea Dworkin has called his work “nearly indescribable.” She writes, “In sheer quantity of horror, it is unparalleled in the history of writing. In its fanatical and fully realized commitment to depicting and reveling in torture and murder to gratify lust, it raises the question so central to pornography as a genre: why? why did someone do . . . this? In Sade’s case, the motive most often named is revenge against a society that persecuted him. This explanation does not take into account the fact that Sade was a sexual predator and that the pornography he created was part of that predation.” Dworkin also notes that “Sade’s violation of sexual and social boundaries, in his writings and in his life, is seen as inherently revolutionary.”

Despite all they seem to share in common, most of today’s radicals actually don’t revere the Marquis de Sade. Rather, they look to his followers; namely, one postmodern philosopher by the name of Michel Foucault, no small fan of Sade, whom he famously dubbed a “dead God.”

Foucault’s ideas remain some of the most influential within the radical Left. He has catalyzed more than one generation with his critiques of capitalism, his rallying cries for what he calls “social war,” and his apparently subversive sexuality. Foucault, who in fact lamented that the Marquis de Sade had “not gone far enough,” was determined to push the limits of sexual transgression, using both philosophy and his own body. His legacy of eroticizing pain and domination has unfortunately endured.

So where are the radicals in this fight against pornography? The answer depends on who we call radical. The word radical means “to the root.” Radicals dig to the roots of oppression and start taking action there—except, apparently, when it comes to the oppression of women. How radical is it to stop digging half way for the sake of getting off?

What is called the radical Left today isn’t really that. It’s radical in name only and looks more like an obscure collection of failing subcultures than any kind of oppositional movement. But this is the radical Left we have, and this one, far from fighting it, revels in porn.

Just as we need to wrest our culture from the hands of the pornographers, we need to wrest our political movements from the hands of the sexists. Until we do that, so-called “radical” men will continue to prop up sexual exploitation under the excusing banner of freedom and subversion.

This male-dominated radical Left is expressly anti-feminist. In a popular and obscene anarchist essay, “Feminism as Fascism,” the author—who is male, need I mention—ridicules feminists for drawing any connection whatsoever between porn and violence against women. He concludes that feminism—rather than, say, the multi-billion dollar porn industry—is a “ludicrous, hate-filled, authoritarian, sexist, dogmatic construct which revolutionaries accord an unmerited legitimacy by taking it seriously at all.”

I’ve ceased to be surprised at the virulent use and defense of porn by supposedly radical—and even “anti-sexist”—men. The two have always seemed to me to go hand-in-hand.

My first encounter with radicals was at a punk rock music show in the basement of a stinky party house. I stood awkwardly upstairs, excited but shy. Amidst the raucous crowd, a word caught my ear: “porn.” Then, another word: “scat.” Next, the guys were huddling around a computer. And I was confused . . . until I saw.

More sophisticated than the punks, the anarchist friends I made a few years later used big words to justify their own porn lust. Railing against what they deem censorship, anarchists channel Foucault in imagining themselves a vanguard for free sexual expression, by which they really mean, men’s unbridled entitlement to the use and abuse of women’s bodies. And any who take issue with this must be, as one anarchist put it, “uncomfortable with sex” or—and I’m not making this up—“enemies of freedom.”

The Queer subculture puts the politics of sexual libertarianism into practice. Anything “at odds with the ‘normal’ or legitimate” becomes fair game. One Queer theorist explained in specifics: “Sleaze, perversion, deviance, eccentricity, weirdness, kinkiness, BDSM and smut . . . are central to sex-positive queer anarchist lives,” she wrote. As the lives of the radicals I once counted as comrades began to confirm and give testament to this centrality, I abandoned ship.

Pornography is a significant part of radical subcultures, whether quietly consumed or brazenly paraded. That it made me uncomfortable from the beginning did not, unfortunately, deter me from trying it myself. It seems significant though, that, despite growing up as a boy in a porn culture, my first and last time using porn was while immersed in this particular social scene. Who was there to stop me? With all semblances of feminist principles tossed to the wind, who was there to steer me from the hazards of pornography and towards a path of justice?

The answer is no one. Why? Because the pornographers control the men who control the radical Left. Women may be kept around in the boy’s club—or boy’s cult—but only to be used in one way or another; never as full human beings. How is it a male radical can look honestly in the face of a female comrade and believe her liberation will come through being filmed or photographed nude?

I have a dear neighbor who says, “There’s nothing progressive about treating women like dirt; that’s just what happens already.” My neighbor has little experience in the radical Left, but apparently bounds more common sense than most individuals therein. She, along with many ordinary people I’ve chatted with, have a hard time believing—let alone understanding—that people who think of themselves as radical could actually embrace and defend something as despicable as pornography. If the basic moral conscience of average people allows them to grasp the violence and degradation inherent in porn, we have to ask: what’s wrong with the radical Left?

In a way, this let down is predictable. From ideologues like Sade and Foucault, to the macho rebellion of punk bands like the Sex Pistols, to the anarchist-endorsed Kink.com, justice—for women and for all—has been a periphery goal at best for countercultural revolutionaries. Of vastly greater priority is this notion of transgression, an attempt at “sexual dissidence and subversion which challenges the symbolic order,” the devout belief that anything not considered “normal” is radical by default.

I can’t speak for you, but there are plenty of things that I think deserve not to be seen as normal. Take Kink.com, for example. Despite the cheerleading of shock value crusaders, I don’t really care how many cultural boundaries the company believes itself to be transgressing; tying up and peeing on another human being is simply wrong. If this sentiment gets me kicked out of some sort of radical consensus, so be it.

What is transgressive for some is business-as-usual oppression for others. As Sheila Jeffreys explains, “Transgression is a pleasure of the powerful, who can imagine themselves deliciously naughty. It depends on the maintenance of conventional morality. There would be nothing to outrage, and the delicious naughtiness would vanish, if serious social change took place. The transgressors and the moralists depend mutually upon each other, locked in a binary relationship which defeats rather than enables change.” Transgression, she contests, “is not a strategy available to the housewife, the prostituted woman, or the abused child. They are the objects of transgression, rather than its subjects.”

Being radical is a process, not an outcome. To be radical means keeping our eyes on justice at every instance, in every circumstance. It means maintaining the agenda of justice when picking our issues and the strategy and tactics we use to take them on. Within a patriarchy, men cannot be radical without fighting sexism. This is to say that radical activism and pornography are fundamentally at odds. Where are the radicals fighting porn? The ones worth the name are already in the heat of battle, and on the side of justice, whether or not it gets us off.

As for the rest, we’re going to have to make them. As the current radical Left self-destructs under the crushing grip of misogyny—as it already is and inevitably will—it is up to us to gather from the rubble whatever fragmented pieces of good there are left. And it is up to us to forge those pieces into a genuinely radical alternative.

Women have been doing this work for a long time. But it is by and for men that women’s lives are stolen and degraded through pornography. And it is by and for men that the radical Left colludes with this injustice. So it must now be men—the ones with any sense of empathy or moral obligation left—who take final responsibility for stopping it. Women have already mapped out the road from here to justice. Men simply need to get on board.

It’s no easy task taking on the cult of masculinity from the inside, but it’s a privileged position in comparison to being on the outside and, thus, its target. And this cult needs to be dismantled. Men need to take it down inside and out, from the most personal sense to the most global.

Men can start small by boycotting porn in our own lives, both for the sake of our individual sexualities and for the sake of the many women undoubtedly suffering for its production. Through images of dehumanized women, pornography dehumanizes also the men who consume them.

Individual rejection of pornography is necessary, but social change has always been a group project. Men must put pressure on other men to stop supporting, and at the very least stop participating in, sexual exploitation. We can demand our movements and organizations outspokenly oppose it. We can disavow them if they refuse.

As it stands, it’s hard to tell apart the radical Left and porn culture at large. Both are based on the same rotten lie: women are objects to be publicly used.

As it falls, the male-dominated radical Left can be replaced by something new and so desperately needed: a feminist, anti-pornography radical Left. Its goal: not the transgression of basic human rights, but the uncompromising defense of them.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.