by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 11, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: With support from Survival, the Guajajara are able to expose illegal logging and threats to their uncontacted neighbors in real time. © Survival

by Sarah Shenker / Survival International

“We are here,” says Olimpio, looking directly into the camera, “… Monitoring the land and protecting the uncontacted Indians and the Guajajara who live here. Why? Because there are some people – anthropologists from some countries – who want, once again, to violate the rights of the uncontacted Indians in the country.”

Olimpio remains calm, but you can sense tension as he continues to speak.

“We are aware that some anthropologists have been calling for ‘controlled contact’ with the uncontacted Indians… We will not allow this to happen, because it would be another genocide.”

Olimpio is among the leaders of a group known as the “Guajajara Guardians,” men from the Guajajara tribe in Brazil’s Maranhão state who have taken it upon themselves to protect what remains of this north-eastern edge of the Amazon rainforest, the hundreds of Guajajara families who call it home, and their far less numerous neighbors: the Awá Indians, some of whom are uncontacted.

Uncontacted tribes are the most vulnerable peoples on the planet, and the Guajajara are acutely aware of this. Whole populations are being wiped out by violence from outsiders who steal their land and resources, and by diseases like flu and measles to which they have no resistance. The Guajajara know that the destruction of the forest, which the Awá have been dependent on and managed for generations, spells doom for the Awá and the Guajajara alike. All uncontacted peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected. Without it, the Awá simply won’t survive.

The satellite imagery is startling: this territory, known as Arariboia, is an island of green amidst a sea of deforestation in this corner of the Amazon, which has been plundered for its iron ore; opened up by roads and rail; and chopped down for its valuable hardwoods.

The Awá are one of the most vulnerable peoples on the planet. Some of them have no contact with mainstream Brazilian society, though the majority do. © Survival International

The uncontacted nomadic Awá live on a small hill in the centre of this island, where they hunt, fish, and collect fruits and berries. Its forest cover is thicker than that below. Following centuries of invasion, the Awá’s hill has become their refuge. They now number no more than several dozen.

As we looked up towards the uncontacted Arariboia Awá’s forest, it struck me that they really are living on the edge. Following centuries of land invasion and theft, and genocidal violence, they are clinging on against all odds. Preventing their annihilation is a matter of now or never.

I was here to learn about the Guajajara Guardians’ work and to set them up with communications technology as part of Survival International’s Tribal Voice project, which allows remote tribal peoples to send video messages around the globe in real time. It is one of the ways in which we work in partnership with them, and give them a platform to speak to the world. They were very enthusiastic about the possibilities this might offer, allowing them to expose logging and other attacks on Arariboia, and share information from their expeditions to protect their Awá neighbors.

First of all, however, Olimpio decided to record a denunciation of two American academics, Kim Hill and Robert Walker, rejecting outright their calls for forced contact with uncontacted tribes.

“It would be another genocide of a people, of indigenous people, who do not want contact, either with us, or with non-indigenous people” he says. It is hard not to be impressed by his determination.

*

Much of this region of Maranhão doesn’t really feel like the Amazon. The state borders the northeastern coast of Brazil and stretches downwards into the Amazon basin, but you don’t see the thick forests that people generally imagine when they picture the world’s largest rainforest. Instead, much of the area has been given over to agriculture in the form of ranches and plantations, or abandoned after the loggers have had their way with it and moved on.

After driving through countless miles of bleached brown grass, it is refreshing to reach Arariboia. The indigenous territory is home to the Guajajara and Awá peoples. Arariboia and other indigenous territories in the region are virtually the only remaining areas of genuine forest in the state. Crossing the border into indigenous land, things don’t feel all too different at first – in fact, vast swathes of forest in the territory were destroyed by fires last year, believed to have been started by the region’s powerful logging mafia. But the further into the area you head, the more you get the sense that you are in an island of lush greenery in the middle of the destruction so common elsewhere in this part of Brazil.

Olimpio and Franciel, coordinators of the Guajajara Guardians, are determined to protect the forest for their uncontacted Awá neighbors. © Survival

Although it is strictly forbidden under Brazilian law for outsiders to fell trees in indigenous territories, here and elsewhere in the Amazon loggers constantly flaunt this with impunity. Just on the drive up to Arariboia we passed dozens of loggers, their trucks piled high with illegally felled logs. I took a photo of one truck driven by two young men looking particularly pleased with their collection, and realized very quickly that they didn’t care. They do not attempt to hide their faces or their operations as they knew that the local government – largely controlled by the mafias who run this trade – will carry on turning a blind eye.

However, it is harder than ever for bandit loggers to operate in Arariboia. The Guardians, of whom there are around fifty, patrol the forest, monitoring, keeping their eyes open, and notifying the authorities. They do it in shifts, in their own time, with only sporadic financial and logistical support from the Brazilian government, despite its formal commitment to protecting the rainforest and indigenous rights. The work is time-consuming and far too much for a small band of committed volunteers. And it’s dangerous: In recent years, several Guajajara have been assassinated.

Why then, do they do it? I found it difficult to fathom at first. It is common for loggers to intimidate and murder indigenous people, so many feel forced into silent acceptance of the loggers and their activities. Sadly in this part of Brazil, many Guajajara also collaborate with the loggers, hoping to make some money from the trade, which they see as unstoppable. Alienated, threatened, and living on the fringes of a society that barely accepts them, the Guardians’ motivation for self-imposed vigilante duty is not outwardly obvious.

*

The more time I spent with the Guajajara in Arariboia, however, the more it seemed to make sense. Members of the tribe who live in the center of their land, closest to the Awá’s hill, are less integrated into mainstream Brazilian society, and feel a stronger sense of connection to their communal ways. They thrive in the forest, knowing it intimately and practising Guajajara rituals.

While I was there I witnessed one of these – a coming of age ceremony for a Guajajara girl. The tribe considers a girl’s first menstruation to be a hugely significant time, marking the passage into adulthood, and celebrate it as a community. The girl spent a week living in a small hut with a palm frond roof, attended by female relatives who would bring her food. Rather than being a solemn isolation, however, the rite of passage is a great celebration, and the Guajajara frequently burst into song and dance, paint their faces and revel in the girl’s new maturity. The men of the village, though not allowed to enter the hut, often come and stand close to the entrance and join in the singing.

Experiencing this put the Guardians’ desire to protect their forest and fellow indigenous people into context. To them, Arariboia is not a resource to be exploited in the name of “progress” and “civilization” – it is fundamental to who they are. They take great pride in it, protect what is left of it, and feel a deep sense of connection to it.

Survival has been working with the Guardians since 2015. © Survival

“People can’t take their land away from them,” another of the Guardians said to me, outraged, as we trekked through the forest close to one of the logging hotspots, “and they can’t take them away from their land.” He was indicating the Awá’s hill, which towers over the surrounding scrubland and lighter forest and provides a focal point in the landscape. The uncontacted Awá living there have expressed their desire to remain uncontacted, and the Guajajara want to see that desire respected.

Some see the centuries-long battle for survival between the indigenous peoples of the Amazon and the colonizers who exploit and destroy it as hopeless. Some, including the American anthropologists who the Guajajara were so keen to refute, see contact as inevitable and isolated uncontacted peoples as doomed. Deforestation will continue, they claim, and so tribal people will either have to assimilate with the Brazilian mainstream, or else face annihilation.

The Guajajara Guardians see it differently. They know what contact, “development,” and “progress” can mean for tribal peoples. They have watched as more and more of the forest that their ancestors were dependent on and managed for generations has been destroyed. And they’re keen to fight back, by boosting their land protection expeditions which are succeeding in keeping loggers out of some key areas, and by sharing their concerns with the world and encouraging international support.

For any tribal people, land is the key to survival. We’re doing everything we can to secure it for them, and to give them the chance to determine their own futures.

That’s also why Survival is giving the Guajajara, and other tribes, communications technology so they can speak to the world in real time. Their understanding of the problems they and their neighbors face is as astute as anyone’s and they have perceptive things to say about almost every aspect of life today. They are not only the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world, but are also at the forefront of the fight for human rights and self-determination. Maybe it’s time to listen.

Sarah Shenker was in conversation with Survival’s Lewis Evans

Act now to support the Guajajara Guardians

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 9, 2018 | Culture of Resistance

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

The final difference between the alternative culture and a culture of resistance is the issue of spirituality. Remember that the Romantic Movement, arising as it did in opposition to industrialization, upheld Nature as an ideal and mourned a lost “state of nature” for humans. Emotions were privileged as unmediated and authentic. Nonindustrialized peoples were cast as living in that pure state of nature. The Wandervogel idealized medieval peasants, developing a penchant for tunics, folk music, and castles. Writes Keith Melville,

Predictably, this attraction to the peasantry never developed into a firm alliance. For all their vague notions of solidarity with the folk, the German youths did not remain for long among the peasants, nor did they take up political issues on their behalf. What the peasants provided was both an example and a symbol which sharpened the German Youth Movement’s dissent against the mainstream society, against modernity, the industrialized city, and “progress.”86

When the subculture was transplanted to the US, there were no peasants on which the new Nature Boys could model themselves. Peasant blouses and folkwear patterns found a role, but the real exploitation was saved for Native Americans and African Americans. Primitivism, an offshoot of Romanticism, constructs an image of indigenous people as timeless and ahistoric. As I discussed in the beginning of the chapter, this stance denies the indigenous their humanity by ignoring that they, too, make culture. Primitivism sees the indigenous as childlike, sexually unfettered, and at one with the natural world. The indigenous could be either naturally peaceful or uninhibited in their violence, depending on the proclivities of the white viewer. Hence, Jack Kerouac could write:

At lilac evening I walked with every muscle aching among the lights of 27th and Welton in the Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough music, not enough night.87

He’d rather be black? Really? Would he rather have a better chance of going to jail than going to college? Would he rather have only one thirty-eighth the wealth of whites? Would he really want to face fire hoses and lynching for daring to struggle for the right to vote? This is Romanticism at its most offensive, a complete erasure of the painful realities that an oppressed community must endure in favor of the projections of the entitled. And depressingly, it’s all too common across the alternative culture.

The appropriation of Native American religious practices has become so widespread that in 1993 elders issued a statement, “The Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality.” The Declaration was unanimously passed by 500 representatives from forty Lakota tribes and bands. The statement could not be clearer: white people helping themselves to Native American religious practices is destructive enough to be called genocide by the Lakotas. The elders have spoken loud and clear and, indeed, even reaffirmed their statement. We should have learned this in kindergarten: don’t take what’s not yours. Other people’s cultures are not a shopping mall from which the privileged get to pick and choose.

Americans are living on stolen land. The land belongs to people who are still, right now, trying to survive an ongoing genocide. Those people are not relics of some far distant, mythic natural state before history. They live here, and they are very much under assault. Native Americans have the highest alcoholism rate, highest suicide rate, poorest housing, and lowest life expectancy in the United States. From every direction, they’re being pulled apart.

Let’s learn from the mistakes of the Wandervogel. Their interest in peasants had nothing to do with the actual conditions of peasants, nor with the solidarity and loyalty that the rural poor could have used; it had everything to do with their own privileged desires. Judging from my many years of experience with the current alternative culture, nothing has changed. The people who adopt the sacred symbols or religious forms of Native Americans—the pipe ceremony, inipi—do it to fulfill their own perceived needs, even over the Native Americans’ clear protests. These Euro-Americans may sometimes go a step further and try to claim their actions are somehow antiracist, a stunning reversal of reality. It doesn’t matter how much people feel drawn to their own version of Native American spirituality or how much a sweat lodge (in all probability led by a plastic shaman) means to them. No perceived need outweighs the wishes of the culture’s owners. They have said no. Respect starts in hearing no—in fact, it cannot exist without it. Just because something moves you deeply, or even speaks to a painful absence in your life, does not give you permission. As with the Wandervogel, the current alternative culture’s approach is never a call for solidarity and political work with Native Americans. Instead, it’s always about what white people want and feel they have a right to take. They want to have a sweat lodge “experience.” They don’t want to do the hard, often boring, work of reparation and justice. If, in doing that work, the elders invite you to participate in their religion, that’s their call.

Many people have longings for a spiritual practice and a spiritual community. There aren’t any obvious, honorable answers for Euro-Americans. The majority of radicals are repulsed by the authoritarian, militaristic misogyny of the Abrahmic religions. The leftist edges of those religions are where the radicals often congregate, and that’s one option; you don’t have to check your brain at the door, and you usually get a functioning community. But for many of us, the framework is still too alienating, and feels frankly unreformable. These religions have had centuries to prove what kind of culture they can create, and the results don’t inspire confidence.

Next up are the pagans and the Goddess people. Unlike the Abrahmists, they often offer a vision of the cosmos that’s a better fit for radicals. Some of them believe in a pantheon of supernaturals, and show an almost alarming degree of interest in the minutia of the believers’ lives. Other pagans believe in an animist life force: everything is alive, sentient, and sacred. But if the theology is a better fit, the practice is where these religions often fall apart. They may be based on ancient images, but the spiritual practices of paganism are new, created by urban people in a modern context. The rituals often feel awkward, and even embarrassing. We shouldn’t give up on the project; ultimately, we need a new cosmic story and religious practices that will keep people linked to it. But new practices don’t have the depth of tradition or the functioning communities that develop over time.

In order to understand where the pagans have gone astray, it may be helpful to discuss the function of a spiritual tradition. Three elements that seem central are a connection to the divine, communal bonding, and reinforcement of the culture’s ethic. What forms of the sacred are sought by the subculture, and by what paths does it intend to reach them? Obviously a community broad enough to encompass everything from crystal healing to “Celtic Wicca” will have a multitude of specific answers. But taken as a whole, the spiritual impulse has been rerouted to the realm of the psychological—the exact opposite of a religious experience.

By whatever name you wish to call it, the sacred is a realm beyond human description, what William James rightly describes as “ineffable.” The religious experience is one of “overcoming all the usual barriers between the individual and the Absolute … In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness.”88 He describes this experience as one of “enlargement, union, and emancipation.”89 James offers a startlingly accurate description of that ineffable experience. But spiritual enlargement, union, and emancipation do not emerge from a focus on our psychology. We experience them when we leave the prisons of our personal pains and joys by connecting to that mystery that animates everything. The arrow—the spiritual journey—leads out, not in. But like everything else that might lend our lives strength and meaning, spiritual life—and the communities it both needs and creates—has been destroyed by the dictates of capitalism. The single-pointed focus on ourselves as some kind of project is not just predictably narcissistic, but at odds with every religion worth the name. The whole point of a spiritual practice is to experience something beyond our own needs, pains, and desires.

Ten years ago, I attended a weekend workshop called “The Great Goddess Returns.” I was already leery of these events back then, but there was one scholar I wanted to hear. The description, in so many words, offered what many people long to find: support, community, empowerment, relief from pain and isolation, and connection to ourselves, each other, the cosmos. These are valid longings and I don’t mean to dismiss anyone’s struggle with loneliness, alienation, or trauma. My criticism is directed instead at the standard form of the faux solutions into which neopaganism has fallen.

Drumming from a CD thumped softly through the darkened room. A hundred people were told to shut their eyes and imagine a journey back through time to an ancient foremother in a cave. I wasn’t actually sure what the point was, but I didn’t want to cultivate a spiritual Attitude Problem so early in the day, so I visualized. We were then handed a small piece of clay. No talking was allowed to break the sacrosanct if technological drumming. We were told to make something with the clay. Okay. It being March, and I being a gardener, I formed a peapod. Time ticked on. The drumming was more baffling than meaningful. And how long could it take people to mold a brownie size bit of clay? I kept waiting, the drumming kept drumming. Finally we were told to crumble up what we had made. All right. I smooshed up my peapod, and went back to waiting and my internal struggle against the demons of attitude. Boredom is annoying. It’s also really boring. I didn’t want to look around—everyone was hunched over with a gravitas that left me bewildered—but I was starting to feel confused on top of bored. Had I missed the part where they said, “Destroy your sculpture one mote at a time”? Finally, the rapture descended: further instructions. “Make your sculpture again,” came the hushed voice. What? Why? I hadn’t particularly wanted the first peapod. Did I have to make another one? Meanwhile, the drums banged on and on, emphasizing my growing ennui, and again, heads all around me bent to the work of clay like it was Day Six in the Garden. I reformed my peapod, which took about sixty seconds, then waited another eternity. I was ready to have a Serious Talk with whoever invented the drum.

Then the lights were slowly raised, a dawn to this long night of the bored soul. We were quietly divided into groups of ten and given the following instructions: “Talk about what you just experienced.”

Talk about … what? I made a pea pod. I crushed a pea pod. I remade a pea pod. For dramatic tension, I tried not to get bored.

Luckily, I was the seventh person in the circle, which gave me time to recognize the pattern and understand the rules. Because everyone else already understood. Being dwellers in the Land of Psychological Ritual, they knew too well what was expected. First up was a woman in her fifties. I don’t remember what she made with her clay. I do remember what she said. Crumbling up her sculpture brought her back to the worst loss of life, the death of her infant daughter. She cried over her clay, and she cried again while telling us, a group of complete strangers.

The next one up said it was her divorce, that crumbling the clay was the end of marriage. She cried, too.

For the third, the destruction of her clay was the destruction of her child-self when her brother raped her when she was five. She trembled, but didn’t cry.

The fourth woman’s clay was her struggle with cancer.

I had to stop paying attention right about then because I had to figure out what I was going to say.90 But I was also reaching overload. Not because of the pain in these stories—after years as an activist against male violence, I have the emotional skills to handle secondary trauma—but because the pain in their stories deserved respect that this workshop culture actively destroyed. This was a performance of pain, a cheapening of grief and loss that I found repulsive. How authentic to their experiences could these women have been when their response was almost Pavlovian, with tears instead of saliva? Smoosh clay, feel grief. Not knowing the expectation—not having trained myself to produce emotion on demand—I felt very little, beyond annoyance, during the exercise, and a mixture of unease, pity, and repugnance during the “sharing circle.” I had no business hearing such stories. We were strangers. I did not ask for their vulnerability nor did I deserve it. To be told the worst griefs of their lives was a violation both of the dignity such pain deserves and of the natural bonds of human community. This was not a factual disclosure—“I lost my first child when she was an infant”—but a full monty of grief. And it was wrong.

A true intimacy with ourselves and with others will die beneath that exposure. Intimacy requires a slow, cumulative build of safety between people who agree to a relationship, an ongoing connection of care and concern. The performance of pain is essentially a form of bonding over trauma, and people can get addicted to their endorphins. But whatever else it is, it’s not a spiritual practice. It’s not even good psychotherapy, divorced as it is from reflection and guidance. If you’re going to explore the shaping of your past and its impact on the present, that’s what friends are for, and probably what licensed professionals are for.

This “ritual” was, once more, a product of the adolescent brain and the alterna-culture of the ’60s, which imprinted itself unbroken across the self-help workshop culture it stimulated. No amount of background drumming will turn self-obsession and emotional intensity into an experience of what Rudolph Otto named “the numinous.” It will not build a functioning community. “Instant community” is a contradictory as “fast food,” and about as nourishing.

I have done grocery shopping after someone’s surgery, picked up a 2:00 am call to help keep a friend’s first, bottomless drink at bay, and taken friends into my home to die. I’ve also celebrated everything from weddings to Harry Potter releases. True community requires time, respect, and participation; it means, most simply, caring for the people to whom we are committed. A performative ethic is ultimately about self-narration and narcissism, which are the opposite of a communal ethic, and its scripted intensity is an emotional sugar rush. Why would anyone try to make this a religious practice?

I have way too many examples of this ethos to leave me with much hope. Some of the worst instances still make me cringe (white people got invited to an inipi and all I got was this lousy embarrassment?). I’ve been included in indigenous rituals and watched the white neopagans and other alterna-culturites behave abominably. Pretend you got invited to a Catholic Mass: would you start rolling on the floor screaming for your mother as the Catholics approached the rail for communion? And would you later defend this behavior as a self-evidently necessary “catharsis,” “discharge,” or “release of power”? When did pop psychology get elevated to a universal component of religious practice? Meanwhile, do I even need to say, the traditional people would never behave that way either at their own or anyone else’s sacred ceremonies. And they’d rather die than do it naked. Their dignity, the long stretches of quiet, the humility before the mystery, all build toward an active receptivity to the spiritual realm and whatever dwells there. The performative endorphin rush is a grasping at empty intensity that will never lead out of the self and into the all. Nor will it strengthen interpersonal bonds or reinforce the community’s ethics, unless those ethics are a self-indulgent and increasingly pornified hedonism, in which case it’s doomed to failure anyway.

So we’re stuck with some primary human needs and, as yet, no way to fill them. Many of us have traveled a continuum of spiritual communities and practices and found that none of them fit. My attempts to name cultural appropriation in the alternative culture have been largely met with hostility. For me, grief has given way to acceptance. The forces misdirecting attempts to “indigenize” Euro-Americans and other settlers/immigrants have been in motion since the Wandervogel. I will not be able to find or create an authentic and honorable spiritual practice or community in my lifetime. All I can do is lay out the problems as I see them and perhaps some guidelines and hope that, over time, something better emerges. It will take generations, but it’s not a project we can abandon.

Humans are hard-wired for spiritual ecstasy. We are hungry animals who need to be taught how to participate, respectfully and humbly, in the cycles of death and rebirth on which our lives depend. We’re social creatures who need behavioral norms to form and guide us if our cultures are to be decent places to live. We’re suffering individuals, faced with the human condition of loss and mortality, who will look for solace and grace. We also look for beauty. Soaring music produces an endorphin release in most people. And you don’t even need to believe in anything beyond the physical plane to agree with most of the above.

Some white people say they want to “reindigenize,” that they want a spiritual connection to the land where they live. That requires building a relationship to that place. That place is actually millions of creatures, the vast majority too small for us to see, all working together to create more life. Some of them create oxygen; many more create soil; some create habitat, like beavers making wetlands. To indigenize means offering friendship to all of them. That means getting to know them, their histories, their needs, their joys and sorrows. It means respecting their boundaries and committing to their care. It means learning to listen, which requires turning off the chatter and static of the self. Maybe then they will speak to you or even offer you help. All of them are under assault right now: every biome, each living community is being pulled to pieces, 200 species at a time. It’s a thirty-year mystery to me how the neopagans can claim to worship the earth and, with few exceptions, be indifferent to fighting for it. There’s a vague liberalism but no clarion call to action. That needs to change if this fledgling religion wants to make any reasonable claim to a moral framework that sacrilizes the earth. If the sacred doesn’t deserve defense, then what ever will?

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 6, 2018 | Women & Radical Feminism

Featured image: Yuly Chan, a founding member of Chinatown Action Group. The smearing, harassment, no-platforming, and silencing of women who express feminist opinions about gender and prostitution is unacceptable.

by Cherry Smiley / Feminist Current

I can’t remember the exact words, who said it or when, but the general message was: courage isn’t the lack of fear, but doing something even when you’re afraid. I am writing this with lots of fear about a backlash that will almost certainly happen. However, I’ve reached the point where I can’t stay silent any longer and need to muster whatever courage I can and do what I think is right, regardless of the cost.

This past week, a woman I’m proud to call a sister ally, Yuly Chan, was no-platformed by a small group of individuals who appointed themselves judge and jury of acceptable ideas and speech. They claimed Chan was a violent, hateful woman whose political opinions were too dangerous to be shared in a public venue and demanded she be removed from a panel scheduled as part of this weekend’s Vancouver Crossroads conference. Chan had been invited by conference organizers, the Vancouver District and Labour Council (VLDC), the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), and Organize BC, to speak on behalf of her group, the Chinatown Action Group. The Chinatown Action Group organizes to improve the lives of low-income residents of Vancouver’s Chinatown, many of whom are seniors. She was to speak to the incredibly important work of this group at the conference.

A recently-formed group called the Coalition Against Trans Antagonism (CATA) wrote a letter to the organizers, then an open letter that included a link to a website CATA had built, documenting supposed evidence of Chan as a threat to public safety. Although Chan was not speaking on the panel about debates around gender or prostitution, Organize BC members interrogated Chan about her politics regarding these issues and eventually refused to move ahead with the panel unless she was removed. Instead of condemning the unethical tactics and behaviour of CATA, intended to silence Chan and smear her as a hate-filled oppressor, the organizers cancelled the entire panel, sending a message that the organizers and their supporters were not willing to take a stand to ensure the needs of low-income Chinese residents were heard. As a result, the Chinatown Action Group was no-platformed right along with their representative.

CATA also demanded that the conference organizers issue a public apology for daring to invite Chan to speak about the activism of low-income Chinese residents of Vancouver. They also demanded that a policy be instituted with the guidance and approval of only “trans women and sex workers,” banning anyone “who promote[s] any form of oppressive, supremacist, and fascist ideology from being offered and/or provided a platform at any of VDLC, CUPE, and Organize BC’s future events.” But who decides which ideologies are “oppressive, supremacist, and fascist”? And why, in activist and academic circles, has it become common and acceptable to engage in witch hunts to rid “the community” (that is made up of whom?) of particular political positions that are grounded not in hate or violence, but in a radical feminist analysis (radical meaning “the root”)? Chan, and so many others who question and critique systems of power are being persecuted for having these feminist or critical politics. It is not violent oppressors, supremacists, or fascists that are being silenced and no-platformed in this case and others like it, it is feminists. There are limits, of course, to the idea of “free speech,” but what I am addressing is specifically discourse among activists and academics on the left.

Organize BC privately and publicly apologized to CATA for inviting Yuly Chan to speak on the panel. But I will not apologize for standing next to Chan and the Chinatown Action Group, and next to all people who have been no-platformed, threatened, intimidated, bullied, and even beaten for their political opinions.

What was Chan’s crime? Having a political analysis and sharing it. She is accused of promoting “SWERF/TERF” ideology. “SWERF” stands for “sex worker exclusionary radical feminist,” and “TERF” stands for “trans exclusionary radical feminist.” These terms are used as insults against women with a radical feminist or class analysis of prostitution and gender. “SWERFs” and “TERFs” are accused of hating, oppressing, harming, and sometimes even killing trans women and sex workers, despite the fact no feminist engages in these practices.

I am of the political opinion that prostitution is a form of male violence that should be abolished. I am also of the political opinion that gender is a social construct and hierarchy that traps and harms women and should also be abolished. Today, these two sentences are enough to mark me as a violent, hate-filled, supremacist/fascist, and have the ability to destroy my reputation, livelihood, and potential academic or employment opportunities now and in the future. I have already been passed over for some opportunities due to my political analysis of prostitution, asked to leave conferences, told I’m not allowed to speak about prostitution when invited to speak about Indigenous research, and threatened with police involvement. I have been intimidated and harassed due only to my politics, not my behaviour. These are only some examples of some of the backlash that I, and other women, have experienced for speaking our opinions. This backlash, however, doesn’t just include no-platforming, but also threats and acts of violence. To many, this may sound unbelievable, as though I am exaggerating. I wish this were the case. I wish I were exaggerating. Unfortunately, this is the reality of activist and academic circles in Canada and elsewhere.

Speaking of academia, in 2016 I was publicly accused online of being an oppressive “SWERF” and “TERF” by a former employee of the Centre for Gender Advocacy at Concordia University, where I am a student. This is the first time I am speaking publicly about this incident, as I have been too afraid to do so since it happened. Although this individual is no longer employed by the Centre for Gender Advocacy, going on instead to become the president of the Fédération des femmes du Québec (FFQ), this issue has not been resolved. In the public post, I was accused of oppressing sex workers and being “transphobic,” funders and the university were tagged, a quote was attributed to me that I never said, and individuals went on a hunt to dig up evidence of my supposed bigotry. One person attempted to publicly engage in discussion about these allegations against me, which I’m grateful for, but they were not heard. Some faculty members were concerned that a staff person at a student support organization was making these types of public allegations about a student and alerted some in positions of power at the University, but got little, if any, response. The manager of the Centre for Gender Advocacy was made aware of the situation, and I am not aware of anything that was or is being done to resolve and rectify the situation. No one has reached out to me to apologize for the online bullying I had experienced, or to speak about concerns or questions they had about my politics, leading me to believe this type of hostility is directed at me not only by one staff member, but the Centre for Gender Advocacy as an organization. I explored different options myself, but was unable to find a way to formally hold the individual and Centre to account. I attempted to find support at the University, but those I approached refused to speak out against the behaviour of the individual and the Centre.

Regardless of your politics, this behaviour is unacceptable. It is not ok to tell lies about people or subject them to political persecution over disagreements. It’s important to note that the Centre houses Missing Justice, an Indigenous solidarity group that hosts the march for murdered and disappeared Indigenous women and girls every year in Montreal. As an Indigenous woman who works on these issues, I was already alienated from Missing Justice when, a number of years ago, non-Indigenous organizers told me to stop speaking and attempted to literally grab a megaphone out of my hand when I was invited to make a statement at their gathering by another Indigenous speaker. My crime was a decolonizing and feminist critical analysis of prostitution and speaking out against men buying sexual access to Indigenous women and girls. In other words, my crime was having a political opinion that differed from the organizers. Rather than attempting to silence an Indigenous woman at an event supposedly held for Indigenous women, a better way forward would have been to publicly acknowledge at the event that my statement does not reflect the organizer’s politics and to encourage those in attendance to learn more about the issue.

Although this incident happened many years ago and the online bullying at Concordia happened two years ago, it continues to severely impact my life as a student in different ways. The message I received from the inaction by the University and the Centre for Gender Advocacy is that it is entirely acceptable to attempt to silence those who are critical of prostitution. I still hear this message today. I feel fear about publicizing these experiences. The very fact that I feel intensely afraid to speak about my own experiences speaks volumes about the climate of activism and academia today.

These incidents are bigger than Yuly Chan and bigger than myself. They have and continue to happen against women with a radical feminist analysis of prostitution and gender. Campaigns are launched against us to silence us, destroy our reputations, paint us as violent, hateful, and oppressive fascists. A 61-year-old woman was even physically assaulted by a young trans-identified male for daring to show up to attend a panel discussing gender and legislation in England.

Regardless of your perspective on prostitution or gender, you have a right to be heard. This means that I may not agree with you and I may challenge your ideas, and you may not agree with me and challenge my ideas, but you have a right to your political analysis and to share that publicly, as do I. Threatening women (for example, tweeting that “TERFS” should be raped or killed), destroying women’s reputations, and compromising women’s incomes is completely unacceptable behaviour. This is not how we build and maintain relationships. Relationships with political allies are incredibly important, but so too are the relationships between political adversaries. These relationships are much more difficult and challenging to navigate, but maintaining good relations means being respectful even to those we may disagree with or dislike. Being respectful can mean you passionately disagree, that you challenge ideas and behaviour — even that you express frustration or anger — but always recognizing the humanity of the person you disagree with. “SWERF” and “TERF” are made up categories of women — they are not accurate descriptors of anyone’s politics, certainly not the politics of feminists. These terms take away the ability of women to name ourselves and describe our own political positions – a situation all too familiar for Indigenous women.

Disagreement is not violence, and I worry about the impacts of the term “violence” being redefined to mean almost anything, rendering it meaningless. Causing offense is not the same as committing violence. Words are not violence. Words can call for violence, yes, but being critical of prostitution and gender is not calling for any type of violence. Rather, this is a legitimate critical analysis of systems that impact us all. Words and images can contribute to a culture that devalues some, and for many reasons, encourage, normalize, or passively accept acts of violence, but to say that making a statement others find offensive or that challenges their political analysis equates to literal violence right then and there is inaccurate, and is a means to silence those of us who hold critical feminist opinions. This new definition of “violence” also impacts women who doexperience male violence, such as rape, physical assault, murder, or emotional abuse, to name just a few examples.

The name of the conference, “Crossroads,” speaks to our current culture, which silences women deemed dangerous. We are at a crossroads: we can choose to open up dialogue and encourage respectful disagreement and really work to hear from as many as we can who are impacted by an issue — even if the political position is unpopular — or we can choose to let only a few individuals decide that radical political opinions are dangerous, and allow them to dictate the terms of their and other people’s public engagement with those ideas; then silence, threaten, intimidate, and attempt to harm anyone who does not agree with their politics.

Doing nothing is no longer an option — staying silent only gives more power to those who wish to silence women with politics that differ from their own.

I stand with Yuly Chan, the Chinatown Action Group, and all women who have dared to speak up and share their critical perspectives on prostitution and gender. I’m proud to be considered a dangerous woman, as I try to be as dangerous to the patriarchy as possible. As women, we are trained to tolerate, accept, and accommodate patriarchy, racism, capitalism, and colonization.

Too often, activists and academics who claim to be working for justice choose to side with individuals who use bully tactics to shut women that they don’t agree with up. There is nothing new or progressive or inclusive or diverse about telling feminist women to shut up. A strategy grounded in recognizing another’s humanity would include engaging, debating, and disagreeing passionately and respectfully at public events or holding an event to highlight one’s own particular political analysis and engaging in public discussion and advocacy around the issue at hand. Silencing women considered dangerous for having thoughts and sharing them is not how we treat each other when we recognize each other as equals.

I encourage all dangerous women and allies to speak out against the no-platforming and assault on women who express radical feminist opinions or critical ideas about prostitution and gender.

Cherry Smiley is a Nlaka’pamux and Diné feminist who refuses to be silent.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 1, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

by Laura Hobson Herlihy / Cultural Survival

The Miskitu Yatama (Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka/Children of the Mother Earth) organization remained silent during last week’s violent protests in Nicaragua, ignited by the government’s April 16, 2018 approval of social security reforms. Many Miskitu people on the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast claimed the Instituto Nicaragüense de Seguridad Social (INSS) reform was not their fight, as Miskitu fisherman and lobster divers were excluded from the national system of social security and would not retire with pensions. Yet, they were supportive of the larger issue of the protests — the end of the Ortega dictatorship.

The Yatama Youth Organization released a statement on April 25, 2018, a week after the protests began, affirming their solidarity with the Nicaraguan university students now calling for President Ortega to step down. That evening by phone, the long-term Yatama Director and Nicaraguan congressman Brooklyn Rivera framed Yatama’s fight solely within the framework of Indigenous rights. Rivera stated, “We are still fighting for the same rights we have always fought for.” The Miskitu leader mentioned their right to saneamiento (the removal of mestizo colonists from Indian lands), as stipulated by Nicaraguan law 445; elections by ley consuetudinaria (customary law) in the autonomous regions, as ruled by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; and fortification of the autonomy process (law 28).

Like an elderly statesman, Brooklyn Rivera sounded hopeful that he could use his position as an opposition congressman in the National Assembly to advance Indigenous rights during the up-coming dialogue for peace with Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) government, to be mediated this Sunday by the Catholic Church and headed by Cardinal Leopoldo Brenes. The interviewer suggested that Yatama is well-positioned as an opposition party to the FSLN in the up-coming regional elections in November 2018. Rivera insisted, “Yatama will not enter any elections if there is not electoral reform first.”

Fraudulent Elections: A History of Violence

Yatama broke their alliance (2006-2014) with the Sandinistas, partially due to alleged electoral fraud during the 2014 regional elections. Indeed, Yatama claimed the FSLN stole the last three elections–the 2014 regional, the 2016 general, and the 2017 municipal elections. After each election, Yatama held peaceful marches but were met with force and attacked by the police, antimotines (riot police) sent from Managua, and the Juventud Sandinista (armed Sandinista youth gangs).

In the 2017 municipal elections, Yatama lost control of its remaining municipalities in the North (RACN) and South (RACS) Caribbean Autonomous Regions. Violence erupted in three towns along the coast. In Bilwi, the capital of the RACN, the police and riot police (antimotines) stood by watching as paramilitary Sandinista turbas (youth gangs) burned Yatama headquarters and radio Yapti Tasba to the ground, toppled the Indian statue in the town center, subverted the green Yatama flag with a black and red FSLN flag, and attempted to shoot Yatama leader Brooklyn Rivera, who escaped.

Police arrested one-hundred Yatama members and detained them in jail for more than a month. Like the university students recently persecuted by the FSLN in Managua, Yatama peaceful protestors were called ‘delincuentes’ and accused of looting stores and setting fires to public property. The state criminalized both groups of protestors–Yatama sympathizers and university students– to justify using force against them. Similarly, the state attacked, detained, disappeared, and murdered university students last week in Nicaragua. Captured and shared through social media, the vivid videos of government repression served to vindicate, support, and liberate the formerly criminalized Yatama protestors.

Yatama Reaction to Protests

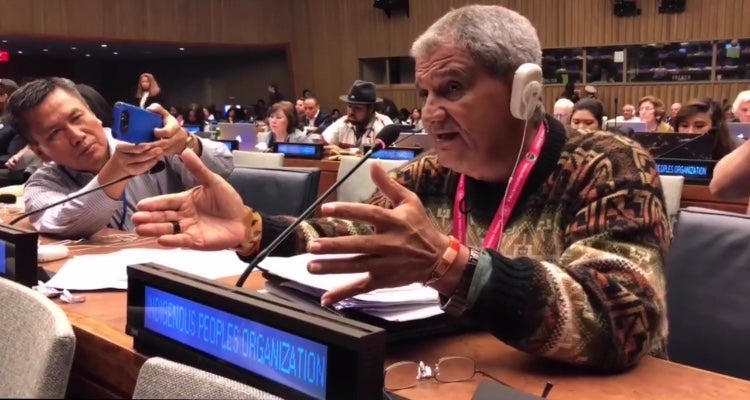

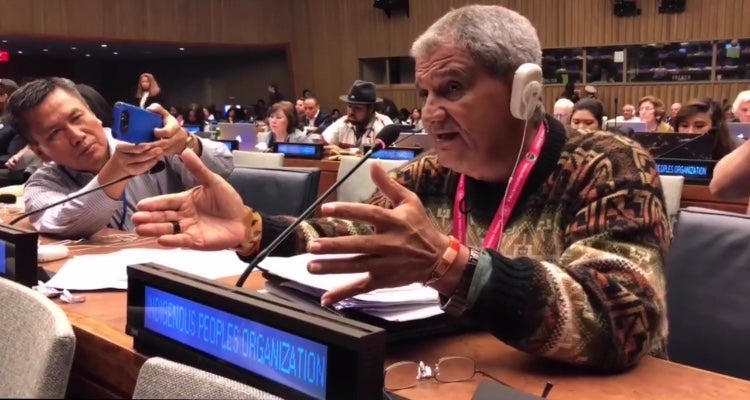

Yatama Director and Nicaraguan Congressman Brooklyn Rivera giving an intervention at the 2018 UNPFII

Yatama members remained glued to their smart phones and social media all week, watching university students fight and broader society organize massive protest marches in Managua. They replayed the video up-loads of the fall of Chayopalos, the metal trees of life placed across the capital that have come to symbolize the First Lady/Vice President Rosario Murillo’s overreaching power and the government’s wasteful spending of scarce resources. Like a dream come true, they envisioned the Ortega-Murillos stepping down from power.

Rivera was busy fighting for Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights at the 2018 United Nations Permanent Forum of Indigenous Issues in New York, when the protests began in Nicaragua. He commented in retrospect, “I was not surprised by the protests. The Nicaraguan people are tired of the Ortega regime.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 22, 2018 | Movement Building & Support

by Wolfs Wands at GoFundMe

March 16th, Mark Wolf and Coyote participated in a non-violent direct action to prevent trucks and trailers from accessing Yellowstone National Park’s Capture Facility. This winter alone Yellowstone has captured and killed more than 1,000 bison. 3,600 bison remain in the wild. After blocking road access for more than 5 hours, Yellowstone officials created a makeshift road so the trucks and trailers could pass by to pick up the bison. Eventually Yellowstone Police removed Wolf & Coyote and they were arrested. Spending five days in jail they met their fates in federal court. Sentenced to two misdemeanors and $1,936 in restituion Yellowstone as well as court fees Wolf and Coyote are asking for donations from other activists and animal lovers that are opposed to the slaughter and displacement of wildlife. These men made a sacrifice of their freedom in order to protect wildlife. Please contribute to their cause today!

For more info on the American Bison please visit Buffalo Field Campaign

Visit the following links for articles related to this action:

Men Block Road to Yellowstone Buffalo Trap

Yellowstone Bison Slaughter Protester Pleads Guilty

2 more protesting bison slaughter arrested for blocking access road in Yellowstone National Park

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: Typical Bonda house in Baunsupada village. The Bondas have always led sustainable lives in the forest, but deforestation and changes in traditional farming practices now threaten their survival. Photo: Abhijit Mohanty.

by Abhijit Mohanty / Intercontinental Cry

The road to Bondaghati winds through the hills and forests of Malkangiri district, on Odisha’s southern edge. As you enter the area, the tar road fizzles out into multiple footpaths leading towards Bonda villages with thatch and clay tile huts. The area is popularly known as Bondaghati because it is home to one of India’s particularly vulnerable tribes – the Bonda. There are 32 villages covering around 130 square kilometres. According to the census 2011, there are around 12000 Bonda populations.

The Bonda houses are arranged one above the other in uneven terraces. Raibaru Sisa, of Bondapada village, explains that “before the construction of a new house, we consult with our traditional astrologer. He performs a divination to find out the suitability and auspiciousness of the proposed site. Only after the identification of an ideal site for the house by the astrologer, we start constructing our house.”

The once-dense forests of Bondaghati sustained the Bonda for centuries. The forest provided fire wood, grazing land and forest produce such as fruits, tubers, roots, honey, mushrooms, medicinal herbs that they could barter. There was an abundance of wild boar, barking deer, spotted deer, sloth bears, leopards and birds. As Bonda Sombaru Sisa says, “The forest is our home. If there will be no forest, our community will vanish in no time.”

Over the last two decades, this home has shrunk, wildlife is seldom seen and the community’s dependence on the land has become tenuous. “Now we have to cover more distance to collect firewood, forest produce, and to graze our cattle. Earlier, the forest was dense and located near our village, but now, even after walking kilometres together, we find very few resources,” Budhbari Sisa, a Bonda woman laments.

Firewood is mostly collected by the Bonda women for cooking. Photo: Abhijit Mohanty

In the Bonda community, women are everywhere – gathering forest produce, tilling the land and watching over the crops. They practice shifting cultivation on the slopes – on patches of unevenly terraced plots called birhi land – staying in one place for three to five years before moving on. They begin in December by clearing the bushes and shrubs and in February they set fire to the undergrowth. As a rule they don’t burn fruit-bearing trees like mango, tamarind and jackfruit. In the monsoon month of July, sowing by dibbling begins – millet, paddy, pulses, oilseeds and a few vegetables. “We watch the crops day and night, staying in field huts raised on shifting plots,” says Raibari Muduli, a Bonda woman of Dantipada village.

Bondas eat a range of millets and can survive a drought with traditional hardy varieties. Many of their parabs (festivals) revolve around harvests and hunting. The year begins with Magh Parab in January to mark the ceremonial eating of new rice and the selection of village functionaries.

Bonda Women at the local weekly market at Mudulipada. Photo: Abhijit Mohanty

The biggest festival is Chait Parab held through March to celebrate eating the first mango and the start of the annual hunting season. Though all the festivals are important for the Bondas, Chait Parab holds a unique place in the community.

“Men and boys go out into the forest for the annual hunt. If we come back without anything, we cannot show our faces to others. Therefore, no animal escapes from us. If we get nothing else, we even kill a jackal. Women dance and sing whole day in the streets and in village commons” Dhanurjay Sisa of Kichapada village says.

The contour of changes

The typical Bonda language–known as Remo–is now an endangered tongue because more Bondas are getting familiar with Odia as their primary language of communication. The absence of a script or text for Remo adds to the threat of its extinction. It is also assumed that their rich indigenous wisdom will become a casualty to this loss.

From 1976-77, the government of India set up a Bonda Development Agency in Khairput block. The Integrated Tribal Development Agency was also established in Malkangiri district. They did more harm than good, Jaldhar Muduli says, “Many of our traditional varieties of crops are lost and the yield has reduced. Earlier we used to cultivate a range of millets like ragi, kodo, pearl, little, barnyard along with up-land paddy and pulses on the slopes of the mountain. [The] Government is providing us saplings of fruit orchards, seeds of onion and potato. We cannot survive on these. We need millets, rice to feed our belly. This will give us the strength to work on our Birhi land.”

The Bonda also had strong traditional system for resolving conflicts. In the past, the village council seen was as cultural center of the village and the Naik or village headman would be carefully selected based on seniority and their knowledge of tradition. While performing his duties for the villagers, the Naik would be assisted by the Challan and Barika, village functionaries who were responsible for maintaining law and order in the village.

After a police station was erected at Mudulipada panchayat, the judicial role of the village receded. Now cases of assault and violence are reported directly to the police station. As a result, hundreds of Bondas now languish in jail.

Bonda women usually wear thick, durable skirts called ringa. Their jewellery is headbands made of grass, garlands of coins and colourful beads, metal bangles and rings on their necks. They also shave their heads. The older women believe that by sticking to traditional attire they appease the gods and prevent misfortune.

Laxhma Muduli is busy with her household chores. Photo: Abhijit Mohanty

Laxhma Muduli, of Baunsupada village, says, “We are careful about our attire because we do not like to break our age-old tradition.” But the cheap and easy availability of sarees is inducing younger women to switch over, and further to grow their hair. Men too are changing to shirts and shorts. Even modern cloths has been distributed by various government departments and some local NGOs.

A young Bonda girl wearing a modern gown instead of their traditional Ringa. Photo: Abhijit Mohanty

As the outsider visitors frequented the Bonda regions, this interaction and curiosity have had its disastrous effects on the culture, tradition, age-old wisdom and low carbon footprint life style of the ever-resourceful Bonda community. On the other hand, the Bonda are largely unaware of their contribution towards widening and enriching the scope of global culture.

In the words of Verrier Elwin, one of the eminent scholar of Tribal Studies in India, “Let us teach them that their (tribal’s) own culture, their own arts are the precious things, that we respect and need. When they feel that they can make a contribution to their country, they will feel part of it.”

Dambaru Sisa is the first Bonda to represent his community in the Legislative Assembly. A graduate in mathematics and law from Berhampur University, he wants to work to protect “the unique culture and tradition of our Bonda tribe while giving them access to education and everything that goes with modern civilization. I do not want framed photographs of my people decorating drawing rooms of the rich,” he says.

“I also do not want to influential people making money from government programs meant to usher in development for Bondas,” concludes Sisa.

Abhijit Mohanty is a Delhi-based development professional. He has extensively worked with the indigenous communities in India, Nepal and Cameroon especially on the issues of land, forest and water.