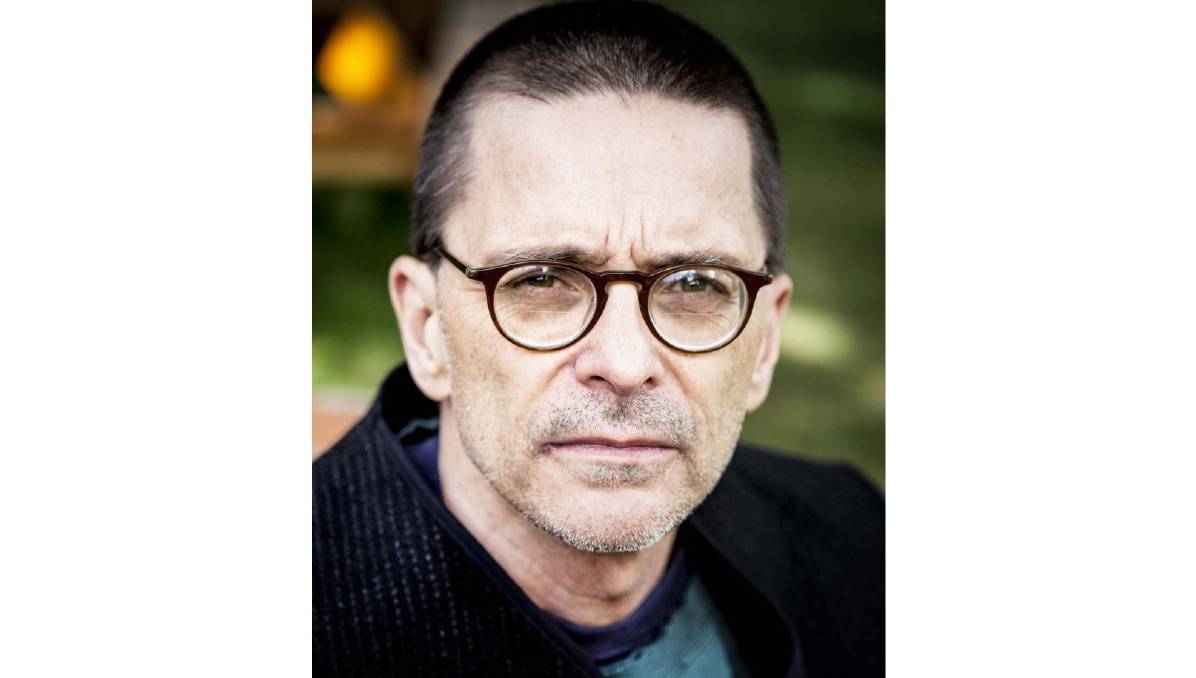

Zoë Goodall interviews Robert Jensen about his most-recent book, “The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men.” by Zoë Goodall/ Feminist Current This month, I had the fantastic opportunity to speak to Robert Jensen while he was in Australia to launch his new book, The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men(2017, Spinifex Press). As a feminist in my early 20s, I was interested to hear how he thought his book would connect with young men, his thoughts on watering down radical feminism to reach a wider range of people, and how his pro-feminist politics relate to his climate change activism. ~~~ Zoë Goodall: You’ve written extensively about various aspects of feminism and patriarchy. What made you decide to produce a more all-encompassing work that examined patriarchy as a whole? Robert Jensen: I wrote a book on pornography that was published in 2007 (which has since gone out of print), and the publishers wanted me to do a new edition of it. I didn’t have the emotional energy to go back, specifically, and do new research on pornography, because it’s exhausting to have to look at the misogyny and the racism. I was thinking a lot about how radical feminism has been so marginalized and that there aren’t that many concise explanations of radical feminism in plain language. I also started thinking about how little is written specifically with a male audience in mind.

I’ve always thought that my role in the world is not to tell women what to think about sex/gender/power, but to speak to men, informed by feminism. It just simply seemed to make sense to write, after nearly 30 years of experience, the best plain language account I could of the feminism that helped me to understand the world.

ZG: Did you write The End of Patriarchy for any particular demographic of men, or do you think it’s broadly applicable to all age groups and classes of men? RJ: I think that the distinctions between men that are important are not primarily among different demographic groups, but internal to them. So, white middle-class men of my age range — some of them are the most sexist human beings I’ve ever met and some of them are the most progressive. The same is true of black urban youth.

Because I teach in a university with a fairly diverse student body, and because I’m out in the world a fair amount, I do see a lot of different men. So I think it’s not that old men are worse than young men, it’s not that white people are worse than black people, that professional men are better than working-class men, you know? I’m sure that there are patterns, but I don’t know enough to know how to describe them. But I’m speaking to anybody within any demographic who wants to think about a radical critique of the sex/gender dynamic, that’s it.

ZG: Over the years, both liberal and radical feminists have expressed sentiments along the lines of “we shouldn’t care what men think — their views aren’t important to us.” Do you think it is important for women in feminism to care about what men think and their viewpoints? RJ: On one level, the question answers itself. If you were a civil rights activist trying to create an anti-racist society, you should probably think about what white people think, because white people are the source of white supremacy and racism. So in some ways, all women who are feminist and concerned about creating gender justice are thinking about men.

The question is: What role do men have in feminist movements? That is a more difficult question. In the radical feminism that I was exposed to, going back to the late 1980s, rooted in the anti-pornography movement, the understanding was that men had a role in the anti-pornography movement — not to take leadership positions, but to contribute to feminist organizations that were speaking to women as well as to men, specifically about ending the use of pornography, but also about using men’s resources. In terms of contributions to the movement, those resources mean money, time, and energy. That always seemed pretty sensible to me. I was quickly clear that my role was to speak to men and use whatever resources I had, which at this point in my life are a university position which gives me status, some amount of money, and my writing skills.

What I’ve always understood about my own writing is that I’m not the smartest person in the room. I’ve been aware of that for a long, long time. What I also came to understand is that I don’t need to be the smartest person in the room to say something clearly that can be useful, especially to men. And the reason I emphasize that is, in academic life you’re conditioned to always be striving to be the smartest person in the room. In a way, I’m glad I started my academic career in feminism, where clearly my role was not to originate new theory — nobody needed me to start pontificating. My role was to take the existing research, theory, and activism of women — which was considerable — and speak about it in a way that men could understand. And to, where possible, add to research. So I’ve done a lot of interviewing of men, for instance, which is something I can do.

So, instead of, like many academics, trying to figure out how I can get out in front and be the big thinker, I’ve always been comfortable with being an interpreter of the really important ideas of other people, including of all these feminist women who’ve done so much amazing work, and especially Andrea Dworkin. You know, the first feminist work I read was by Andrea Dworkin [pause]. I get really emotional about her, because she had such a huge influence on my life that sometimes when I say her name, I stop and I think, “Oh my god, she’s dead,” you know? And she died so young. But I read Andrea’s work first, and am I going to improve on Andrea Dworkin’s understanding of men and pornography? Not likely. But I can take those insights of hers and ask how I can explore them and how I can talk to men about them. So that’s what I do.

ZG: What are your thoughts on the watering down of radical politics to make them more palatable to more people, versus retaining the ideological purity of the movement? Do you think radical politics are still useful even if they are somewhat defanged? RJ: I would first of all distinguish between “watering down,” which is always dangerous, and “dejargoning,” if you’ll accept that term. Like any other intellectual, political movement, people can develop an insider language — jargon. And I think jargon is destructive, both to our ability to communicate with others, but also to our own understanding. The minute people start relying on jargon instead of argument, the quality of the intellectual and political position erodes. So I’ve always tried to write without jargon, but to write radically.

I don’t feel a need to water [radical ideas] down, for two reasons. One is I’m an intellectual in the big sense — that society gives me enough money that I don’t have to grow my own food. I get to sit around and think about things. It’s my job, in that sense, to do that. And two, at this point, liberal institutions — capitalism, traditional governance structures, the industrial model for how human beings should operate — aren’t working. At some level, a lot of people know they aren’t working. If you give people only a new version of the same old institutions that people know aren’t working, you’re not going to activate and inspire people. I think what people are looking for, increasingly, is something that is radical. And by that I don’t mean posturing radically — I mean a truly deep critique that goes to the root and speaks to people.

Now, you put a hundred people in a room, a radical analysis is not necessarily going to resonate with [all of them]. But I would rather speak to the percentage of them that are ready for that than to try to create some message that appeals to the broadest possible segment of that room, because that will inevitably lead to a message that doesn’t inspire and won’t be embraced by very many people. At this moment, I’m more convinced than ever that we need to be more radical. But to be radical in plain language.

ZG: Many feminists who are critical of the sex industry refute the accusation that their analysis is based on moralism, most likely because this has been used as a reason to discount their arguments. However, in The End of Patriarchy, you embrace a moral critique of pornography and prostitution, arguing that your position is based, in part, on moral judgments. Were you worried that this statement might create a backlash, not only from defenders of the sex industry, but also from feminists who have rejected claims that their criticisms are based on morals? Why was articulating a moral basis to your objections important to you? Do you think that other men should feel the same? RJ: I think everybody should feel the same. What I would distinguish is between moral claims and moral principles versus a kind of a moral ism used to signify people who assert — with moral certainty — the way you should behave or the way you should use your body, for instance. So I try to avoid being moralistic in that sense — that pejorative sense — but to recognize that we are always, constantly, inextricably moral beings.

Politics is always based on a moral theory of some sort, about what it means to be human. So I use the term “moral” in that larger sense, and I think because the right wing — especially the religious right — has captured the term “morality” and defined it in such narrow ways, many people in the liberal, left, and secular world are afraid of it. I think we need to reclaim it. And the reason is twofold:

Principles. Because I don’t think there is a way to develop a politics without basing something on foundationally moral claims.

Because everybody really wants moral answers. It’s part of being human.

When the left and the liberals cede that moral turf to the right, the right fills it. And they fill it with what I think are bad answers. So rather than give up that territory and say, “Well we’re not making moral judgments,” I say, “Yes, I’m making moral judgments, and I can articulate them and I can defend them.” Because I think, at some level, people understand there is no decent human community without moral principles. By moral principles I don’t mean, “You can’t use your penis in a certain way,” I mean, “What does it mean to be a human being in relation to other humans? What do we owe ourselves? What do we owe others? How do we understand ourselves in the larger living world?”

All those are profoundly moral questions. Because they have to do with what it means to be a human being. So I embrace that, on both practical and principled grounds.

ZG: Have you noticed men’s attitudes towards women and/or feminism change over the decades? Do you think it’s gotten better or worse? RJ: I’m going to speak only in the U.S. context, because that’s what I know. In the nearly 30 years I’ve been paying attention to this, the general cultural climate for feminism has gotten better, it’s gotten worse, and it’s stayed the same. Depending on the kinds of issues we’re talking about, all of those things are true.

Let’s take the presence of women in existing institutions: education, government, business. That’s better. We just had an election in which, for the first time, a woman was a major contender for the top political office. That’s an improvement. It doesn’t mean I like Hillary Clinton’s politics, but it’s an improvement — that got better. On some things — take general household relationships, your average heterosexual married couple — I think that’s pretty much the same as it was 30 years ago. I don’t think there have been great improvements in the deepening of a real feminist presence in people’s everyday lives. On the sexual exploitation industries — pornography, prostitution, stripping — it’s far worse, we’ve lost ground. There’s more pornography, there’s more of an acceptance of prostitution than there’s ever been.

So, all of those things are true — that’s the complexity of modern society.

ZG: Do you think young men today have more or less hope of understanding the messages in The End of Patriarchy? Because on the one hand, we’re the generation that’s grown up in a porn culture. But on the other hand, we’re the generation where feminism of a certain kind has become relatively mainstream. RJ: With experience, there’s the possibility of deeper insight. Yet age and experience can also make it difficult for us to see new ideas. Both things are true. I think my experience suggests that, again, there’s no predicting. Young men who will identify as feminists, but identify with a very kind of weak, liberal, tepid feminism are in some ways as much — maybe even more — of an impediment to making progress than older, lefty guys who may not know how to speak about this so much, but have a more intuitive notion of “justice has to include something around a critique of patriarchy.”

Younger men are growing up in a world that is both more corrosive and also more open to feminism. So how does that balance out? Here’s one way to say it: Are members of fraternities at U.S. universities any more feminist-friendly than they were 40 years ago? Well, they might have learned a certain language. But the fact is, fraternities are still rape factories, and there’s been no significant shift to change that. So, both things are true. Fraternity men know the language, but they don’t care.

ZG: In the concluding chapter of The End of Patriarchy, you talk about the ever-worsening damage to the planet enacted through human activity. Climate change is essentially the definitive crisis of our generation; we’ve been made aware that it’s a problem since we were born, and it’s our generation who needs to fix things before it’s too late. How do you see radical feminism as part of the solution to these ecological crises? RJ: The connection is twofold: one is intellectual, and the other is more embodied. The two foundational hierarchies in human history, you could say, are the human claim to own the world and men’s claim to own women. After the invention of agriculture, human beings started routinely saying “we own the world”, eventually expanding to “we own every inch of the world and we can do what we want with it”. Patriarchy begins in men’s claims to own women’s bodies, especially reproduction and sexuality. There’s something about this that’s very important, that the two oldest oppressions, in a sense, of patriarchy and human domination of the world, both share this pathological belief that we can own things. And eventually that developed into slavery and believing you can own other humans for labour, and you know, that nation-states can own other territories.

For the last couple of years I’ve really been thinking about how pathological the concept of ownership really is. So if we’re going to deal with reversing the human destruction of our own ecosystem, it’s got to be with rethinking what it means to own. Which to me, among other things, means there is no human future in capitalism, which is premised on the market and the ownership of all.

That’s kind of an analytical answer. There’s always an analytical component to politics, but there’s also an embodied and emotional component, and for me, the feeling is the same. When I listen to women describing their experiences of being prostituted, it’s not just an intellectual response, it’s something deeply human and empathetic in my response in that. I’m from the state of North Dakota, in the U.S., and North Dakota is largely an agricultural state. But in western North Dakota, fracking has opened up an oil industry. I’m not from that part of the state, but it feels like home, in a sense, and when I see pictures of what fracking has done to the land in North Dakota, I cry. There’s a connection, and it’s not because it’s “my land,” it’s because that feels like my part of the world, and there is something being done to destroy that world. It’s a very similar embodied and emotional reaction.

I think there’s something to that. If we are going to deal with the ecological crises, it can’t simply be by analytically deciding we can’t burn fossil fuels anymore, or we need to get solar panels. There’s got to be some way that we transcend our isolation from the larger living world. Modern society keeps you isolated: stay in front of a screen, stay in an air-conditioned house.

We’ve got to deal with that. My first entry into feeling with my own body and understanding my own body was feminism, which told me that all that pornographic culture I had been seduced by was keeping me from myself. There was something profound about that. And I begin the book talking about the bodily experience of coming into feminism.

Zoë Goodall is a student and writer based in Melbourne, Australia. She is currently completing her Honours at RMIT University, examining discussions relating to Indigenous women that occurred during the deliberations on Canada’s Bill C-36. She tweets infrequently at @zcgoodall.