Excerpted from Chapter 8, “Organizational Structure,” of the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet by Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Aric McBay.

The most basic organizational unit is the affinity group. A group of fewer than a dozen people is a good compromise between groups too large to be socially functional, and too small to carry out important tasks. The activist’s affinity group has a mirror in the underground cell, and in the military squad. Groups this size are small enough for participatory decision making to take place, or in the case of a hierarchal group, for orders to be relayed quickly and easily.

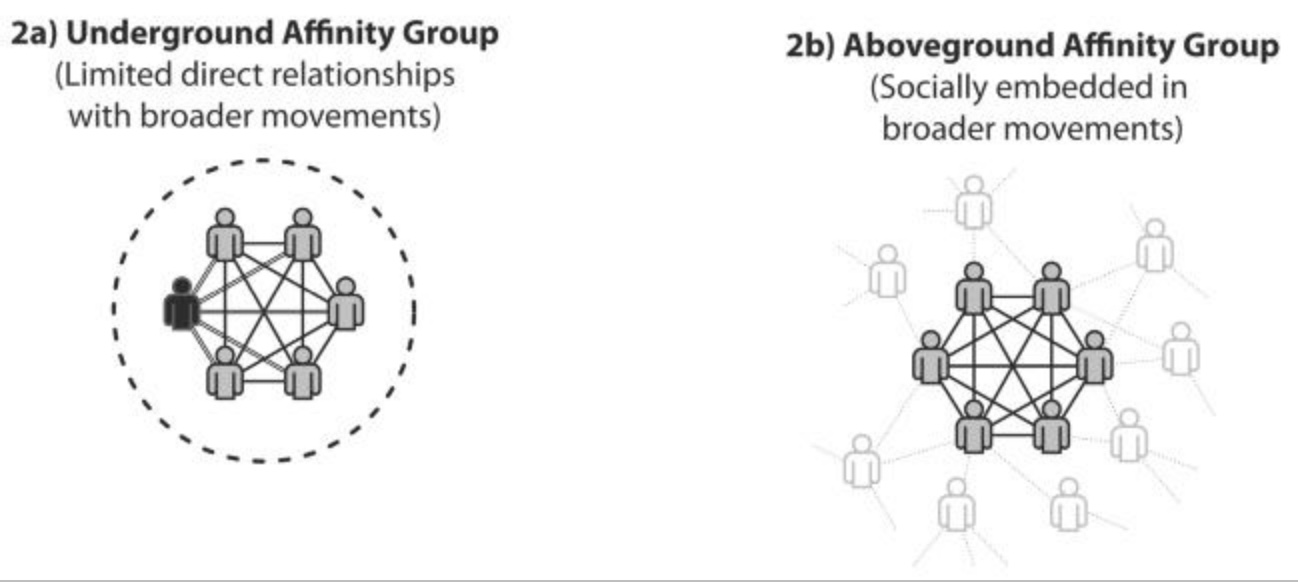

The underground affinity group (Figure 8-2a, shown here with a distinct leader) has many benefits for the members. Members can specialize in different areas of expertise, pool their efforts, work together toward shared goals, and watch each others’ backs. The group can also offer social and emotional support that is much needed for people working underground. Because they do not have direct relationships with other movements or underground groups, they can be relatively secure. However, due to their close working relationships, if one member of the group is compromised, the entire affinity group is likely to be compromised. The more members are in the group, the more risk involved (and the more different relationships to deal with). Also because the affinity group is limited in size, it is limited in terms of the size of objectives it can go after, and their geographic range.

Aboveground affinity groups (Figure 8-2b) share many of the same clear benefits of a small-scale, deliberate community. However, they may rely more on outside relationships, both for friends and fellow activists. Members may also easily belong to more than one affinity group to follow their own interests and passions. This is not the case with underground groups—members must belong only to one affinity group or they are putting all groups at risk.

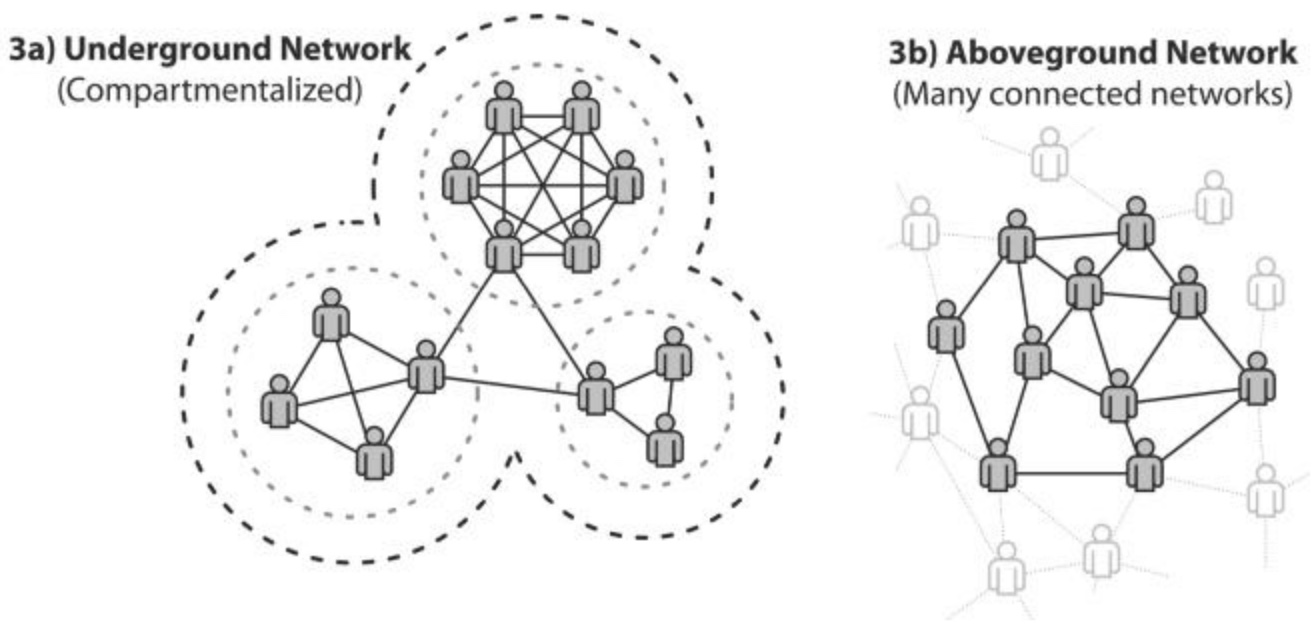

The obvious benefit of multiple overlapping aboveground groups is the formation of larger movements or “mesh” networks (Figure 8-3b). These larger, diverse groups are better able to get a lot done, although sometimes they can have coordination or unity problems if they grow beyond a certain size. In naturally forming social networks, each member of the group is likely to be only a few degrees of separation from any other person. This can be fantastic for sharing information or finding new contacts. However, for a group concerned about security issues, this type of organization is a disaster. If any individual were compromised, that person could easily compromise large numbers of people. Even if some members of the network can’t be compromised, the sheer number of connections between people makes it easy to just bypass the people who can’t be compromised. The kind of decentralized network that makes social networks so robust is a security nightmare.

Underground groups that want to bring larger numbers of people into the organization must take a different approach. A security-conscious underground network will largely consist of a number of different cells with limited connections to other cells (Figure 8-3a). One person in a cell would know all of the members in that cell, as well as a single member in another cell or two. This allows coordination and shared information between cells. This network is “compartmentalized.” Like all underground groups, it has a firewall between itself and the aboveground. But there are also different, internal firewalls between sections.

Such a network does have downsides. Having only a single link between cells is beneficial, in that if one cell is compromised, it is much more difficult to compromise other cells. However, the connection is also more brittle. If a “liaison” is removed from the network or loses communication for whatever reason, then the network may be broken up. A backup plan for regaining communication can reduce the damage from this, but increase the level of risk. Also, the nonhierarchal nature of this network means that choosing actions can be more difficult. The more cells are involved, the larger the number of people who must have critical information in order to make decisions. That said, these groups can be very effective and functional. The famous Underground Railroad was a decentralized underground network.

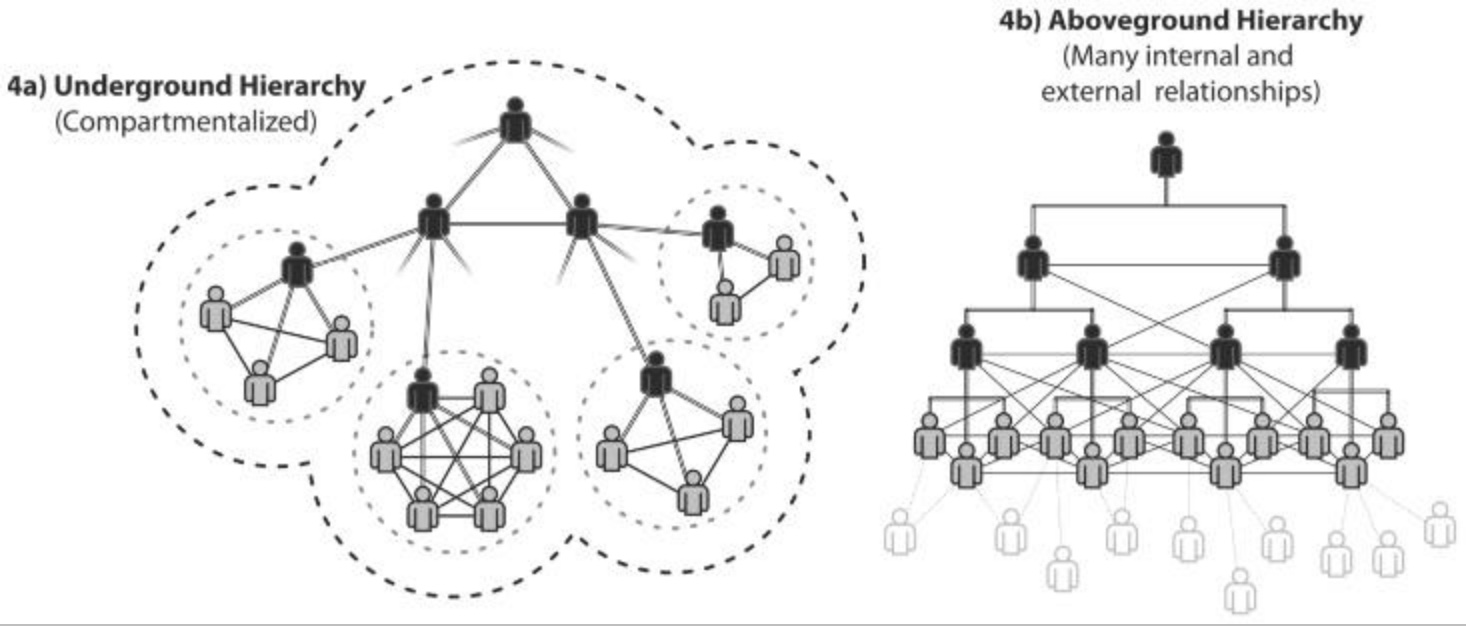

Some of these problems are addressed in both aboveground and underground groups through the use of a hierarchy. In underground hierarchies (Figure 8-4a), large numbers of cells can be connected and coordinated through branching, pyramidal structures. These types of groups have vastly greater potential than smaller networks. Their numbers make for increased risk, yes, but that increased risk can be reduced by the use of specialized counterintelligence cells within the network and wide-ranging coordinated attacks.

Aboveground hierarchies (Figure 8-4b) are quite familiar and common, in part because they are highly effective ways of coordinating large numbers of people to accomplish a specific objective. As shown, aboveground hierarchies facilitate many relationships between people in different parts of the hierarchy. This lack of compartmentalization might be good in terms of productivity, but not in terms of security.

There are very specific situations in which it may be acceptable to send information through an underground group’s firewall. The recruitment process necessarily involves communication with people outside the group. However, these people would not be active in aboveground movements, and, at least initially, they would only know one member of the organization in one cell. Of course, there are no direct relationships between people in the underground and aboveground groups.

In certain situations, one-way (and likely anonymous) communications may take place across the firewall. Informants who want to give information to the resistance network may pass on information to a member of an internal intelligence group. However, the intelligence group would not share information about identities or the network with those people. Information may also travel one-way in the opposite direction. The underground groups may want to send communiqués or other information to the media or press office. Of course, any communication across the firewall, even those thought anonymous, entails a certain small amount of risk. Therefore, the benefits must outweigh the risks.

All of the examples illustrated are simplified and generalized. Resistance groups in history have had a wide variety of internal structures based on these general templates. They often had to make a deliberate compromise between organizational security (which comes from loosely connected and decentralized cells) and organizational effectiveness (which comes from more densely connected and centralized cells).