by DGR News Service | Aug 4, 2014 | Colonialism & Conquest, Lobbying

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance San Diego

There’s a common joke I’ve heard many indigenous people tell. It goes like this: “What did indigenous peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? OURS.”

This joke – or truth – reflects many of the problems inhering to the Supreme Court of Canada’s recent ruling in Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44. From my radical view, the Tsilhqot’in decision leaves much to worry about. In this article, I examine the decision written by Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin to show why the decision is not as helpful it would seem and I anticipate how the government and corporations will bend the decision to their goals.

For me, the term “radical” denotes going to the roots of the problem. First Nations are suffering under the yoke of colonialism. Colonialism is the problem. To undermine colonialism, we must understand the processes making colonialism possible. One of the most powerful institutions perpetuating colonialism is the Canadian government and the Canadian court system as a branch of the Canadian government. It is my view that – for now – we must read the Tsilhqot’in decision not so much as a victory, but as another step down the long road of insidious colonialism.

First, there’s the general and underlying defeat that comes with the fact that colonialism has been so dominant in Canada that First Nations must submit to decisions made by Canadian courts. My second problem with the decision involves facing that there can be no true ownership of land when a dominated people must ask the courts of their conquerors for validation of their right to their own homelands. Placing the burden on First Nations to prove their land claims is another act of arbitrary power that works against cultural survival. Finally, I am deeply anxious about how clearly the Court spells out just what kind of governmental projects would be the type that the Court would sign off on. These projects include mining, forestry, agriculture, and the “general economic development of the interior of British Columbia.”

What Appealing to the Legal System Means

When celebrating what we view as a “good” decision by an imperial court it is easy to forget that the goal is to dismantle the power that gives the court its authority. We must not begin to view the so-called justice system as something like a benevolent paternal figure to appeal to when big-bad corporations come to destroy the land.

We must never forget that there will never be true justice in the courts of the oppressors because the courts of the oppressors are designed to protect the oppressors. Private property laws are the perfect example of this. What happens if you’re starving, walk into Walmart, take a loaf of bread, and are caught? You will be charged with transgressing property laws, dragged into court, and punished by the court for your transgression. Walmart’s right to a loaf of bread trumps your right to eat.

What does it mean, for example, that the Tsilhqot’in had to ask the courts to give them a right to land that they have lived on for thousands of years? Can a people ever truly own their land if they have to ask an occupying court to recognize their claims to land? The court protected the Tsilhqot’in after twenty-five years of deliberation, but what happens to the next aboriginal group that appeals to the courts and loses?

How is Aboriginal Title Established?

First, the Court lays out the process for establishing Aboriginal title. The burden falls on the Aboriginal group claiming title to prove its title. This means that a First Nation existing on its land for thousands of years must pay lawyers and subject its people to the stress of a legal proceeding – in courts established by settlers with access to First Nations land through centuries of genocide – to prove that the land is, in fact, theirs.

Aboriginal title is based on an Aboriginal group’s occupation of a certain tract of land prior to assertion of European sovereignty. A group claiming Aboriginal title must prove three characteristics about their occupation of a certain tract of land. First, they must prove their occupation is sufficient. Second, they must prove their occupation was continuous. Third, they must prove exclusive historic occupation. (¶ 50)

Proving Sufficient Occupation

To prove sufficiency of occupation, an Aboriginal group must demonstrate that they occupied the land in question from both an Aboriginal perspective and a common law perspective.

The Aboriginal perspective “focuses on law, practices, customs, and traditions of the group” claiming title. In considering this perspective for the purpose of Aboriginal title, the court “must take into account the group’s size, manner of life, material resources, and technological abilities, and the character of the lands claimed.” (¶ 35)

The common law perspective comes from the European tradition of property law and requires Aboriginal groups to prove they possessed and controlled the lands in question. As the Court explains, “At common law, possession extends beyond sites that are physically occupied, like a house, to surrounding lands that are used and over which effective control is exercised.” (¶ 36)

Simply put, proving sufficiency of occupation requires that the group claiming Aboriginal title were involved with the land in question more deeply than just using it in passing.

Proving Continuity of Occupation

Proving a continuity of occupation “simply means that for evidence of present occupation to establish an inference of pre-sovereignty occupation, the present occupation must be rooted in pre-sovereignty times.” So, the group claiming Aboriginal title must provide evidence that they were on the land in question in pre-sovereignty times. (¶ 46)

Exclusivity of Occupation

The last of the three general requirements for establishing Aboriginal title burdens a group with proving they have had the intention and capacity to retain exclusive control over the lands in question. As with sufficiency of occupation, the exclusivity element requires that the court view the evidence from both the Aboriginal and common law perspectives. According to the Court, “Exclusivity can be established by proof that others were excluded from the land, or by proof that others were only allowed access to the land with the permission of the claimant group. The fact that permission was requested and granted or refused, or that treaties were made with other groups, may show intention and capacity to control the land.” (¶ 48)

What Rights Does Aboriginal Title Confer?

This is one of the most important issues addressed by the Court in Tsilhqot’in – for what it says and what it does not say. The important thing to know here is that Aboriginal title does not provide Aboriginal groups with complete control of their own land. It may be common sense to assume that once an Aboriginal group gains Aboriginal title to their ancestral lands they are free to use their land how they see fit free of government interference. This simply is not true. And the Court is very clear to explain that this is not true.

According to the Court, “Aboriginal title confers ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land.” (¶73)

In the English common law, “fee simple” refers to the highest form of ownership of land. Traditional rights associated with “fee simple” are the ones mentioned in the quote above. As the Court explains, “Analogies to other forms of property ownership – for example, fee simple – may help us understand aspects of Aboriginal title. But they cannot dictate what it is and what it is not.” (¶72) The Court quotes Delgamuukw, “Aboriginal title is not equated with fee simple ownership; nor can it be described with reference to traditional property law concepts.”(¶72)

It is important to note, of course, that Aboriginal title does not actually give Aboriginal groups full ownership of their own land. Aboriginal title has some key restrictions.

The Court explains: Aboriginal title “is collective title held not only for the present generation but for all succeeding generations. This means it cannot be alienated except to the Crown or encumbered in ways that would prevent future generations of the group from using and enjoying it. Nor can the land be developed or misused in a way that would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land. Some changes – even permanent changes – to the land may be possible. Whether a particular use is irreconcilable with the ability of succeeding generations from the land will be a matter to be determined when the issue arises.” (¶74)

So, once Aboriginal title is established, Aboriginal groups can only sell or give their land back to the Crown. On top of this, the Court creates open doors for future litigation with all the restrictions. Aboriginal groups will be subject to defending their decisions from accusations that they do not know how to manage their own lands for the benefit of future generations. Forcing Aboriginal groups to defend their actions in Canadian courts is a statement that the courts know how to manage Aboriginal lands better than Aboriginal peoples.

Finally, through Tsilhqot’in, Aboriginal title is subject to being over-ridden by governments and other groups on the basis of the broader public good – which often spells disaster for First Nations and natural communities.

Infringing on Aboriginal Title

Government and other groups may infringe on Aboriginal title – or use Aboriginal lands against the wishes of aboriginal peoples – on the basis of the broader public good if it “shows (1) that it discharged its duty to consult and accommodate, (2) that its actions were backed by a compelling and substantial objective, and (3) that the governmental action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary obligation to the group.” (¶ 77)

The Duty to Consult

The Court predicates the duty to consult on what it calls the “honour of the Crown” and says that the “reason d’etre” of the duty to consult is the “process of reconciling Aboriginal interests with the broader interests of society as a whole.” (¶77 and 82)

It sets up a sliding scale for adjudicating just how hard the government or other groups must try to consult Aboriginal groups. The duty to consult is strongest where Aboriginal title is proven and weaker where the title is unproven. The Court quotes the Haida decision, “In general, the level of consultation and accommodation required is proportionate to the strength of the claim and the seriousness of the adverse impact the contemplated governmental action would have on the claimed right. The required level of consultation and accommodation is greatest where title has been established.” (¶ 79)

Nowhere does the Court say that a government or other group must literally accommodate the wishes of Aboriginal groups. Yes, the government has a duty to consult. But, the government is not charged with an absolute duty to respect the wishes of an Aboriginal group with title to land the government wants. No never actually means no when the government is concerned.

Compelling and Substantial Objectives

The Court is very careful to articulate that there are compelling and substantial objectives that would justify infringement on Aboriginal title. Just like we saw with the duty to consult, the Court will view what objectives will justify infringement through a desire to reconcile Aboriginal interests with the broader interests of society as a whole.

On its surface, this sounds great, but then the Court quotes the Delgamuukw decision to illustrate just exactly what kinds of activities might qualify as a compelling and substantial objectives (when reading this list, keep in mind the kinds of projects we are fighting against right now): “The development of agriculture, forestry, mining, and hydroelectric power, the general economic development of the interior of British Columbia, protection of the environment or endangered species, the building infrastructure and the settlement of foreign populations to support those aims, are the kinds of objectives that are consistent with this purpose and, in principle, can justify the infringement of aboriginal title.” (¶ 83)

We have to recognize how dangerous this language is. Enbridge has long anticipated the language. You could pick any number of prominent quotes from Enbridge’s Northern Gateway website www.gatewayfacts.ca to see how Enbridge is already spinning rhetoric to match the Court’s Tsilhqot’in ruling.

Take this one, for example, under the heading, “A boost for our economy,” “Northern Gateway will bring significant and long-lasting fiscal and economic benefits. Economically, the project represents more than $300 billion in additional GDP over 30 years, to the benefit of Canadians from every province.”

Or this one under the heading “Building communities with well-paying jobs,” “The pipeline sector creates thousands of jobs across the country. In B.C. alone, Northern Gateway will help create 3,000 new construction jobs and 560 new long-term jobs. The $32 million per year earned in salaries will directly benefit the families and economies of these communities.”

This is exactly the type of governmental objective that the Court in Tsilhqot’in suggests is compelling and substantive enough to pass constitutional muster.

It is important to understand how easy it is to be misled by our desire for good news in the fight to defend the land and First Nations communities. While there are helpful aspects of the Tsilhqot’in ruling on Aboriginal title, the Court is a long way from giving First Nations total control over their own lands. It may be safer for land defenders to assume that nothing really has changed. Yes, Aboriginal title has been defined, but how meaningful is that title if governments and corporations can override title by pointing to the “general economic development of the interior of British Columbia”?

The Crown’s Fiduciary Duty

The final hurdle a government or other group must clear in infringing on Aboriginal title is proving that the proposed action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary duty to the Aboriginal group. This fiduciary duty supposedly requires the Crown to act solely in Aboriginal groups best interests. The problem, of course, is that it is the courts that decide what is in an Aboriginal groups best interest.

The Court explains that the Crown’s fiduciary duty impacts the infringement justification process in two ways. “First, the Crown’s fiduciary duty means that the government must act in a way that respects the fact that Aboriginal title is a group interest that inheres in present and future generations…This means that incursions on Aboriginal title cannot be justified if they would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land.” (¶ 86)

The second way it impacts the infringement process is by imposing an obligation of proportionality into the justification process where the government’s proposed infringement must be rationally connected to the government’s stated goal, where the government’s proposed action must minimally impair Aboriginal title, and where the benefits the government expects to accrue from the proposed action are not outweighed by adverse effects on Aboriginal communities. (¶ 87)

Another glimpse at the Enbridge’s Northern Gateway website (http://www.gatewayfacts.ca/benefits/economic-benefits/) demonstrates how Enbridge anticipates the Court’s ruling. Under a heading titled “Aboriginal inclusion” the website reads, “First Nations and Metis communities were offered to become equity partners providing them a 10% stake in the project. With the $300 million in estimated employment and contracts, it adds up to $1 billion in total long-term benefits for Aboriginal communities.”

I do not think it is a stretch to expect that Canadian courts will rule that Aboriginal groups denying projects like the Northern Gateway are working contrary to their own best interests. But, this isn’t even really the point. The point is, for all the progressiveness we want the Tsilhqot’in decision to stand for, it still allows the courts to decide what the best interest of First Nations is and not First Nations themselves. The longer this system remains intact, the longer First Nations communities will be in danger.

by DGR News Service | May 21, 2014 | Strategy & Analysis

By Kim Hill / Deep Green Resistance Australia

Life itself has been stolen from us.

Genes, the very basis of life, no longer belong to the living beings who embody them, but to institutions that convert life into profit.

Our basic needs, of food and water, no longer come from the land where we live, but from distant corporations that use the exact same food and water as a dumping ground for their wastes.

Monsanto executives take up positions of power in the US Food and Drug Administration, and Environmental Protection Authority. These bodies, instead of protecting our food and water as they were intended to do, now protect the interests of those who are causing the harm.

Governments exist within the rules of Free Trade Agreements and The World Bank, institutions that exist to protect the profits of corporations. Governments have little power to create change.

So we cannot ask governments to act.

In India, 250,000 farmers have committed suicide by drinking Monsanto pesticides after their Bt cotton crops, sold to them by Monsanto, failed, and they were no longer able to provide for their families. Monsanto obstructs labelling laws, and suppresses the results of research that are not in its favour. It is not going to listen to the demands of the people. The purpose of a corporation is to make profit, regardless of the costs to other people and living beings. It is not possible for it to act in any other interest.

So we cannot ask corporations to act.

Even if Monsanto were stopped, there are plenty of other biotechnology companies ready to take their place. The entire economic system is structured to see living beings only as an opportunity for profits, or as standing in the way of profits. For life to continue, the entire system needs to be dismantled.

It is up to us to act.

As human beings, we are part of a natural community of rivers, forests, soil and myriad living beings. This community provides our food and water.

We need to act, not as consumers, not as citizens, but as humans.

We are accountable not to profits or institutions, but to the land that provides for us.

Actions that ask governments and corporations to change – rallies, petitions and letters – can never be effective on their own. Those who are profiting from the theft of life itself need to be physically stopped.

Every day, people are taking real action, by destroying GM crops, sabotaging equipment and infrastructure, and engaging in cyber-attacks against corporations. These actions are essential to stop Monsanto and all those profiting from the destruction of living communities.

On behalf of those whose lives have been stolen and manipulated for profit, those who cannot speak and cannot act, we need to give our full support to the people who are risking their own lives and freedom to defend life itself.

by DGR News Service | Apr 27, 2014 | Obstruction & Occupation, Toxification

By Dan Collyns / The Guardian

Around 500 Achuar indigenous protesters have occupied Peru’s biggest oil field in the Amazon rainforest near Ecuador to demand the clean-up of decades of contamination from spilled crude oil.

The oilfield operator, Argentine Pluspetrol, said output had fallen by 70% since the protesters occupied its facilities on Monday – a production drop of around 11,000 barrels per day.

Native communities have taken control of a thermoelectric plant, oil tanks and key roads in the Amazonian region of Loreto, where Pluspetrol operates block 1-AB, the company said on Thursday.

Protest leader, Carlos Sandi, told the Guardian that Achuar communities were being “silently poisoned” because the company Pluspetrol has not complied with a 2006 agreement to clean up pollution dating back four decades in oil block 1-AB.

“Almost 80% of our population are sick due to the presence of lead and cadmium in our food and water form the oil contamination,” said Sandi, president of FECONACO, the federation of native communities in the Corrientes River.

Pluspetrol, the biggest oil and natural gas producer in Peru, has operated the oil fields since 2001. It took over from Occidental Petroleum, which began drilling in 1971, and, according to the government, had not cleaned up contamination either.

Last year, Peru declared an environmental state of emergency in the oil field.

But Sandi said the state had failed to take “concrete measures or compensate the native people” for the environmental damage caused.

He claimed Achuar communities were not receiving their share of oil royalties and the state had failed to invest in development programmes in the Tigre, Corrientes and Pastaza river basins that had been most impacted by oil exploitation.

He said the Achuar were demanding to meet with the central government to talk about public health, the environment and the distribution of oil royalties.

“We aren’t against oil exploitation or development we are calling for our rights to be respected in accordance with international laws,” he said.

“Conversations are under way to bring a solution to the impasse,” Pluspetrol told Reuters. “A government commission is there and we hope this is resolved soon.”

Over the past year, the Peruvian government has declared three environmental emergencies in large areas of rainforest near the oil field after finding dangerous levels of pollution on indigenous territories.

Peru’s Environment Ministry said in a statement last week that a commission formed by government and company representatives has been assigned to work with communities to tackle pollution problems and other concerns.

From The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/apr/25/indigenous-protesters-occupy-perus-biggest-amazon-oilfield

by DGR News Service | Apr 6, 2014 | Colonialism & Conquest, Defensive Violence, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Property & Material Destruction

By Mindanao Examiner

New People’s Army rebels on Saturday raided a mining firm in the southern Philippine province of Agusan del Norte, reports said.

Reports said the rebels swooped down on Philippine Alstron Mining Company on the village of Tamamarkay in Tubay town and overpowered the security guards without firing a single shot before they torched several trucks and other heavy equipment.

The rebels also seized at least 6 shot guns and short firearms from the company’s security arsenal. There were no reports of casualties.

The raid came following threats made by the NPA on mining firms operating in the southern Philippines.

Just last month, rebel forces attacked a police base and government troops in Davao del Sur’s Matanao as punishment for their “reign of terror” against indigenous tribes and other communities opposing mining operations in the province.

Dencio Madrigal, a spokesman for the NPA-Valentine Palamine Command, said the deadly attacks were a punishment for police and military units protecting Glencore Xstrata. He accused the mining firm of exploiting nearly 100,000 hectares of ancestral lands of indigenous Lumad Blaans tribes, and peasants in the region.

Jorge Madlos, a regional rebel spokesman, also warned mining firms and fruit plantations in the region, saying military operations in Mindanao have escalated and have become more extensive with the aim to thwart the ever growing and widespread people’s protest against destructive mining operations and plantations.

Madlos said among their targets are Russell Mines and Minerals, Apex Mining Corp. and Philco in southern Mindanao; Dolefil, Del Monte and Sumifru plantations in northern Mindanao; TVI Resource Development Philippines in western Mindanao whose operations inside the ancestral domain of indigenous Subanen and Moro tribes are being opposed by villagers.

NPA and Moro rebels had previously attacked TVI Resources in Zamboanga province.

“If one recalls, more than 400 families were forced to evacuate their ancestral lands because of TVI and the ruthless military operations that ensued to protect it in Buug, Zamboanga del Sur. In order to defend the people’s human rights and general wellbeing, the NPA launched tactical offensives against TVI as well as against units of the AFP-PNP-CAFGU protecting it, such as the ambush on February 2012 that hit elements of the army intelligence group operating on the behest of TVI and the imposition of the local government to allow TVI mining operations on Subanen ancestral lands is one of the bases the NPA raided on April 9, 2012 the PNP station in Tigbao, Zamboanga del Sur,” Madlos said.

NPA rebels also intercepted a group of army soldiers who were using a borrowed truck from TVI and disarmed them in Diplahan town in Zamboanga Sibugay province two years ago. The rebels also burned the truck before releasing the soldiers.

“In view of these events, the NDFP in Mindanao calls upon the Lumad and Moro peoples, peasants and workers, religious and other sectors to further strengthen their unity and their courage to oppose the interests of imperialist mines and plantations, which are exceedingly damaging to Mindanao, to its people and to the environment. We call upon the units of the NPA in Mindanao to be ever more daring in their defense of people’s interests against the greed and rapacity of the local ruling classes and their imperialist master,” Madlos said.

TVI Resource Development Philippines has repeatedly denied all accusations against them. It recently ended its gold mining operation in Mount Canatuan in Zamboanga del Norte’s Siocon town after several years of operations and now has a gold-silver project in the town of Bayog in Zamboanga del Sur province and a nickel plant in Agusan del Norte province.

From Mindanao Examiner: http://www.mindanaoexaminer.com/news.php?news_id=20140405091630

Photo by Matthew De Zen on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Mar 30, 2014 | Male Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

By Kourtney Mitchell / Deep Green Resistance

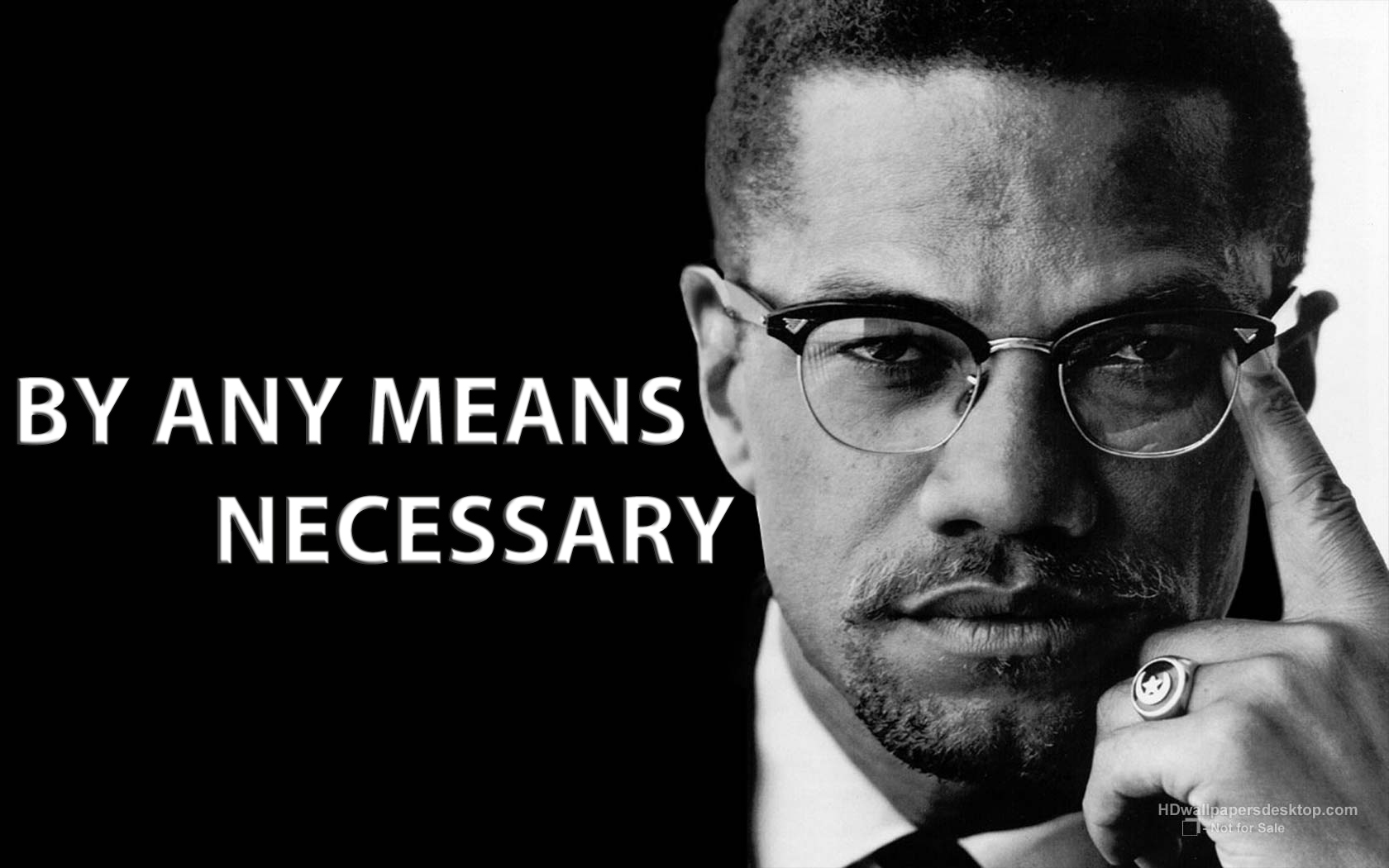

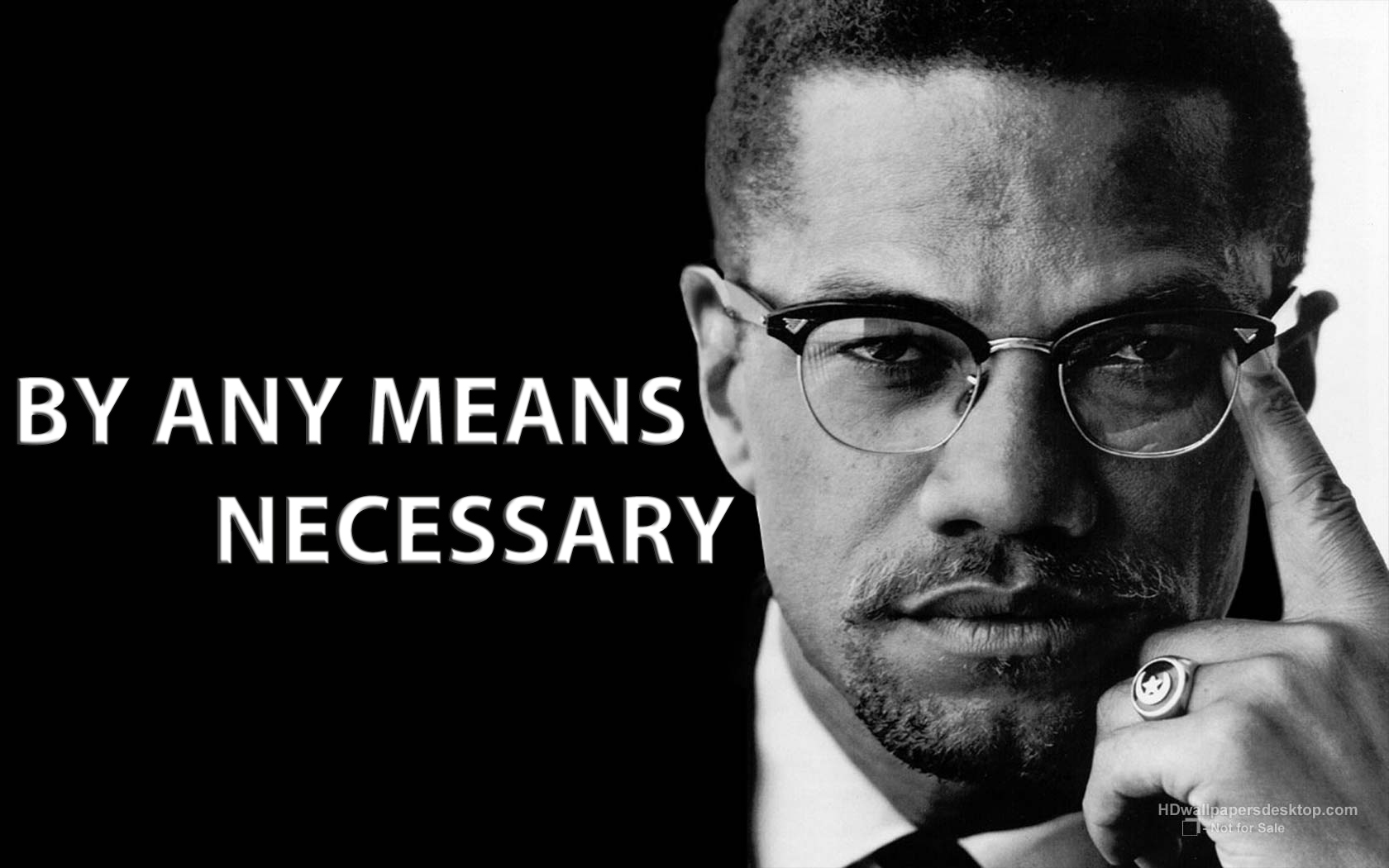

On June 28, 1964, Malcolm X gave a speech at the Founding Rally of the Organization for Afro-American Unity (OAAU) at the Audubon Ballroom in New York. In the speech, he stated what became his most famous quote:

We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.

Interestingly, X was popularizing a line from a play titled Dirty Hands by the French intellectual Jean-Paul Sartre, which debuted in 1948:

I was not the one to invent lies: they were created in a society divided by class and each of us inherited lies when we were born. It is not by refusing to lie that we will abolish lies: it is by eradicating class by any means necessary.

There are some really important ideas presented in both of these quotes. Sartre succinctly summarized the primary struggle for the socially conscious – that society as we know it is divided into classes, and that social change is not achieved merely by refusing to behave like dominant classes, but by ultimately dismantling the power structures upholding this stratification.

X’s spin on this was equally profound. The white power structure of his time enacted brutal and morally reprehensible repression on the masses of black people in the United States, and X was stating the very real yet existential condition: that this repression was a dehumanizing tactic, upheld by violence and enslavement, and that the response to this repression must equal the scope of the problem. Simply put, white supremacism will use any and all means necessary to maintain power, and thus those fighting against it must do the same.

The modern environmental and social justice movement could learn a thing or two from these quotes. Any one who is not meditating in a cave should realize by now that this culture we live in – industrial civilization – is quickly killing the planet. All life support systems on Earth are declining, and have been doing so for several decades. As a matter of fact, since the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, generally considered the birth of the modern environmental movement, there has not been a single peer-reviewed article contradicting that statement.

This should ring some alarms for everyone, but surely for those in the movement, right? One would think so, but unfortunately this does not seem to be the case. Instead, what we are seeing is a continued ignorance of the true scale of environmental destruction, and a refusal to be honest about what it will take to stop it. What we are seeing is a constant faith on popular protest and nonviolence as the end goal of resistance, a hegemonic adherence to pacifism.

At the same time that nearly all native prairies are disappearing, and insect populations are collapsing, and the oceans are being vacuumed, and nearly two hundred species of animals are going extinct every single day, women are also being raped at a rate of one every two minutes. A black male is killed by police or other vigilantes at a rate of one every 28 hours. There are more slaves today than at any time during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. And indigenous cultures and languages are being wiped off the planet.

It is apparently certain that for all of our good intentions – our feelings of loving-kindness, taking the moral high ground and being the change we wish to see in the world – we are failing, and miserably. We are losing.

This must change.

It is time to face the truth, a truth climate scientists, indigenous warriors and anyone who is half awake have been telling us for a really long time – our planet is being killed, and we must fight back to end the destruction before all life on the planet perishes for good.

A starting point for establishing an effective response to environmental destruction and social oppression is to develop a clear understanding of the mechanisms for this arrangement. The dominant classes of people who are enacting this brutality utilize concrete systems of power to do so, namely industrial capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy and human supremacism.

These institutions of power are run by people – human beings, who instead of holding a reverence for life and love of freedom, value privilege and power above all else. This system is based upon, and would quickly collapse without, widespread and pervasive violence. Privilege is upheld by violence, because no one willingly cedes their freedom and autonomy unless forced to do so.

There is a necessary realization one must have when considering all of this, and it is a realization many in the so-called movement are yet to have: as the oppression of human and non-human communities and the destruction of the planet is being enacted by a particular class of people – that is, a group of people sharing a real or perceived identity and having similar goals and the means to achieve those goals – it is also being endured by a particular class of people.

Men, as a class of people whose collective behavior has a very real effect, are oppressing women as a class. This is not to claim that every single man on the planet has some palpable sense of hating women, but it does mean that to be a man in this society is to behave in a socialized manner that oppresses women.

Whites as a class of people are oppressing people of color. This is not to say that every single white-identified person on the planet has some palpable sense of hating people of color, but that to be white in this society is to behave in a manner that oppresses people of color in at least some ways.

If the violence is enacted by classes, the resistance must also exist on the class-level. It has never been enough for the individual to make personal, lifestyle changes so that they can feel better about themselves while the rest of the people in their class suffer. Systems of oppression are not defeated by individuals – they are defeated by organizing with others, a collective struggle.

This is what it means to be radical. As radicals, we aim to get to the root of the problem. Radical anti-racists understand that the white identity is based upon privilege, and that privilege is inherently oppressive to people of color. Radical anti-sexists understand that the concept of gender is built upon male dominance and female submission, which is inherently oppressive to women. And radical environmentalists understand that industrial civilization – based upon extraction, destructive agricultural practices and the genocide of indigenous cultures – is killing the planet.

From there, we draw the line. A radical’s primary goal is not to combat the symptoms of oppression – we do not merely wish to navigate the gender spectrum, toying with it at will as some kind of protest. We wish to abolish gender, recognizing it as the primary basis for women’s oppression. And we do not wish to merely give people of color a bigger slice of the pie in the white supremacist power structure. We wish to abolish white supremacy altogether, and furthermore to overcome the concept of race itself. Radical environmentalists cannot afford to continue to espouse technological fixes for a problem caused by technology and extraction. No, industrial civilization is wholly irredeemable, and no amount of technology can fix it.

What should be apparent is that our movement needs more than nonviolence and good feelings. We need to mount a serious threat to the power structures, one that is forceful and continuous. We need militant action. Those killing the planet will not stop unless forced to do so.

Nonviolence is a powerful tactic when correctly applied, but it alone cannot match the scale of destruction. When coupled with strategic attacks on the infrastructure of oppression, it can result in concrete, lasting change.

And this is the strategy of Deep Green Resistance. As an aboveground movement, we use nonviolent direct action, putting our bodies between life and those who wish to destroy it. Though we have no connection to (and no desire to have a connection with) any underground that may exist, we actively support the formation of an underground, encouraging militant resistance that will bring down oppressive institutions for good.

DGR is also dedicated to the work of helping to rebuild or to build new, sustainable human communities. We are working towards a culture of resistance – where oppression and ecocide are not tolerated, and where people incorporate resistance into their everyday lives. We work to establish solidarity and genuine alliance with oppressed communities, always keeping an eye towards justice, liberating our hearts and minds from the hegemonic tendencies of privileged classes. DGR understands that marginalized communities have been on the front lines of resistance from the very beginning, defending their way of life and reclaiming their autonomy. For too long, pacifists and dogmatic nonviolent activists have left the hard work of actual resistance to those marginalized groups, shying away from the real fight. No more – it is now time for men to combat sexism, for whites to combat racism, and for the civilized of this culture to fight against industrial empire and bring it down.

This analysis and this strategy should be inspiring. But what is more inspiring is that we have the means to achieve our goals. We know how to bring down industrial capitalism, which is controlled by critical nodes of technology and extraction. When these nodes are attacked and brought down in a way preventing their rebuilding, the system begins to collapse. The mechanisms of control – the military, the police and the media – cannot operate without consistent input of fossil fuels and willing agents.

When this system falls, the living world will rejoice. Two hundred species of animals who would have gone extinct will instead live and flourish. Indigenous communities will reclaim their traditional homelands. The salmon will begin to spawn anew with each dam taken down, and the rivers will rush with life.

This is the world for which we fight. And we intend to win.

Let’s Get Free! is a column by Kourtney Mitchell, a writer and activist from Georgia, primarily focusing on anti-oppression and building genuine alliance with oppressed communities. Contact him at kourtney.mitchell@gmail.com.

by DGR News Service | Mar 27, 2014 | People of Color & Anti-racism, Property & Material Destruction, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

By Deep Green Resistance UK

We have had several months to reflect on the life and legacy of Nelson Mandela. Since his death, world leaders have attempted to coopt this legacy. It is especially interesting to see how many who once branded Mandela a terrorist are rushing to pay their respects. [1]

His freedom fighter past has been quietly forgotten. Mainstream writers, intellectuals, and politicians prefer to focus on his life after prison. A simple Google search for Mandela is dominated by articles about tolerance and acceptance.

But often lost in discussions of Mandela are the details about why he was sent to prison by the Apartheid Government. He rose to leadership in the African National Congress (ANC) against Apartheid and his role in the creation of its militant wing, the Umkhonto We Sizwe (MK) which means “Spear of the Nation” in Zulu and Xhosa.

Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom is very well written bringing the reader on Nelson’s journey with him. He dedicated his life to the struggle to create a South Africa where all are equal.

For a detailed summary of Mandela’s path to militant resistance see the DGR Nelson Mandela Resister Profile.

Mandela came from a privileged background and was groomed to council the leaders of his tribe. He received an excellent ‘western’ education. He moved to Johannesburg and trained as a lawyer. In Johannesburg, he came into contact with ANC members. His radicalisation began as he attended ANC meetings and protests.

On page 109 of Mandela’s autobiography he explains that he cannot pinpoint the moment when he knew he would spend his life in the liberation struggle. He states that any African born in South Africa is politicised from birth with the oppression and inequality Africans in South Africa suffer. “I had no epiphany, no singular revelation, no moment of truth, but a steady accumulation of a thousand slights, a thousand indignities and a thousand unremembered moments that produced in me an anger, a rebelliousness, a desire to fight the system that imprisoned my people.”

In 1948, the Nationalist (Apartheid) Party won the general election and formed a government that remained in power until 1994. Following the election, the ANC increased activities resulting in deaths at protests by the police. In response, the government introduced legislation that steadily increased the oppression on Africans in South Africa.

The ANC National Executive including Mandela discussed the necessity for more violent tactics in the early 1950s but it was decided the time was not yet right. Mandela consistently pushed the ANC to consider using violent tactics. During the forced eviction of Sophiatown in 1953, Nelson gave a speech.

As I condemned the government for its ruthlessness and lawlessness, I overstepped the line: I said that the time for passive resistance had ended, that non-violence was a useless strategy and could never overturn a white minority regime bent on retaining its power at any cost. At the end of the day, I said, violence was the only weapon that would destroy apartheid and we must be prepared, in the near future, to use that weapon.

The fired up crowd sang a freedom song with the lyrics ‘There are the enemies, let us take our weapons and attack them’. Nelson pointed at the police and said “There are our enemies!”

Mandela saw that the Nationalist government was making protest impossible. He felt Gandhi had been dealing with a foreign power that was more realistic than the Afrikaners. Mandela knew non-violence resistance works if the opposition is playing by the same rules but if peaceful protest is met with violence then tactics must evolve. For Mandela “non-violence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon.”

This is a lesson that should be learned for the current resistance to the destruction of our world. The current strategy of non-violence in the environmental movement is simply ineffective.

The Sophiatown anti-removal campaign was long running, with rallies twice a week. The final eviction was in February 1955. This campaign confirmed Mandela’s belief that in the end there would be no alternative to violent resistance. Non-violent tactics were met by ‘an iron hand’. “A freedom fighter learns the hard way that it is the oppressor who defines the nature of the struggle. And the oppressed is often left no recourse but to use methods that mirror those of the oppressor. At a certain point, one can only fight fire with fire.”

Following the Sharpville massacre in March 1960, where 69 people were murdered by the police and then the ANC was declared an illegal organisation in April 1960, the National Executive agreed that the time for violence had come:

At the meeting I argued that the state had given us no alternative to violence. I said it was wrong and immoral to subject our people to armed attacks by the state without offering them some kind of alternative. I mentioned again that people on their own had taken up arms. Violence would begin whether we initiated it or not. Would it not be better to guide this violence ourselves, according to principles where we saved lives by attacking symbols of oppression, and not people? If we did not take the lead now, I said, we would soon be latecomers and followers to a movement we did not control.

This new military movement would be a separate and independent organisation, linked to the ANC but fundamentally autonomous. The ANC would still be the main part of the struggle until the time for the military wing was right. “This was a fateful step. For fifty years, the ANC had treated non-violence as a core principle, beyond question or debate. Henceforth the ANC would be a different kind of organisation.”

The parallels with the modern environmental movement’s commitment to non-violence over the last fifty years are uncanny.

The military organisation was named Umkhonto we Sizwe (The Spear of the Nation) or MK for short. Mandela, now underground hiding from the authorities, formed the high command and started recruiting people with relevant knowledge and experience. The mandate was to wage acts of violence against the state. At this point, precisely what form those acts would take was yet to be decided. The intention was to begin with acts least violent to individuals but more damaging to the state.

Mandela began reading and talking to experts especially on guerrilla warfare. In June 1961, Mandela released a letter to the press explaining he continued to fight the state and encouraged everyone to do the same. In October 1961, Mandela moved to Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, where the Umkhonto we Sizwe constitution was drafted.

In planning the direction and form that MK would take, we considered four types of violent activities: sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution. For a small and fledgling army, open revolution was inconceivable. Terrorism inevitably reflected poorly on those who used it, undermining any public support it might otherwise garner. Guerrilla warfare was a possibility, but since the ANC had been reluctant to embrace violence at all, it made sense to start with the form of violence that inflicted the least harm against individuals: sabotage.

Because Sabotage did not involve loss of life, it offered the best hope for reconciliation among the races afterwards. We did not want to start a blood-feud between white and black. Animosity between Afrikaner and Englishman was still sharp fifty years after the Anglo-Boer war; what would race relations be like between white and black if we provoked a civil war? Sabotage had the added virtue of requiring the least manpower.

Our strategy was to make selective forays against military installation, power plants, telephone lines and transportation links; targets that would not only hamper the military effectiveness of the state, but frighten National Party supporters, scare away foreign capital, and weaken the economy. This we hoped would bring the government to the bargaining table. Strict instructions were given to members of MK that we would countenance no loss of life. But if sabotage did not produce the results we wanted, we were prepared to move on to the next stage: guerrilla warfare and terrorism.

DGR is following a similar strategy in the hope that we can transition to a truly sustainable society. We think that its unlikely that those in power will allow this. So phase four of the DGR strategy Decisive Ecological Warfare calls for decisive dismantling of all infrastructure.

On December 16th 1961, MK carried out its first operation. “Homemade bombs were exploded at electric power stations and government offices in Johannesburgh, Port Elizabeth and Durban. On the same day, thousands of leaflets were circulated around the country announcing the birth of Umkhonto we Sizwe. The attacks took the government by surprise and “shocked white South Africans into the realization that they were sitting on top of a volcano”. Black South Africans now knew that the ANC was no longer a passive resistance organisation. A second attack was carried out on New Year’s Eve.

Nelson was arrested in 1962 for inciting persons to strike illegally (during the 1961 stay-at-home campaign) and that of leaving the country without a valid passport. During this trial he gave his famous ‘Black man in a white court‘ speech. Nelson was sentenced to five years in prison.

In May 1963, Nelson and a number of other political prisoners were moved to Robben Island and forced to do long days of manual labour. Then in July 1963, Nelson and a number of other prisoners were back in court, now charged with sabotage. There had been a police raid at the MK Rivonia farm during a MK meeting where they had been discussing Operation Mayibuye, a plan for guerrilla warfare in South Africa. A number of documents about Operation Mayibuye were seized.

What become known as the Rivonia Trial begin on October 9th, 1963 in Pretoria. Huge crowds of supporters gathered outside the court each day and the eleven accused could hear the singing and chanting. The Crown concluded its case at the end of February 1964, with the defence to respond in April.

Right from the start we had made it clear that we intended to use the trial not as a test of the law but as a platform for our beliefs. We would not deny, for example, that we had been responsible for acts of sabotage. We would not deny that a group of us had turned away from non-violence. We were not concerned with getting off or lessening our punishment, but with making the trial strengthen the cause for which we were struggling – at whatever cost to ourselves. We would not defend ourselves in a legal sense so much as in a moral sense. We saw the trial as a continuation of the struggle by other means.

Then on April 20th, 1964, Nelson gave his famous ‘I am prepared to die’ speech. Three important sections are:

“I must deal immediately and at some length with the question of violence. Some of the things so far told to the Court are true and some are untrue. I do not, however, deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the Whites.”

“We of the ANC had always stood for a non-racial democracy, and we shrank from any action which might drive the races further apart than they already were. But the hard facts were that fifty years of non-violence had brought the African people nothing but more and more repressive legislation, and fewer and fewer rights.”

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

Eight of the eleven, including Nelson were sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island. These eight had been expecting the death sentence. Nelson was released after 27 years in prison on February 11th, 1990.

He was aware that his family suffered because of his focus but knew that the needs of the many in South Africa were more important than the needs of the few. It is important to remember that Nelson Mandela and his family are only human, with faults and issues. His first wife accused him of domestic violence, which he always denied. His second wife is accused of ordering a number of brutal acts while Mandela was in prison. And some of Mandela’s children found him difficult. [2]

It is true that Mandela embraced non-violence upon his release from prison in 1990. But, he did this once he felt the disintegration of Apartheid was inevitable. Despite what the vast majority of media coverage would have us believe, a combined strategy of violence and non-violence were necessary to bring down Apartheid.

DGR is committed to stopping the destruction of the world. We recognize that combined tactics are necessary. As Mandela did, we need a calm and sober assessment of the political situation. It is a situation that is murdering the world. We need to leave every tactic on the table whether it is violent or non-violent. There simply isn’t enough time to restrict ourselves to exclusively non-violent tactics.

References

[1] http://www.forbes.com/sites/rickungar/2013/12/06/when-conservatives-branded-nelson-mandela-a-terrorist/

[2] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2349335/Nelson-Mandela-death-ballroom-dancing-ladies-man-tempestuous-love-life.html

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org