This is the eleventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more. via Deep Green Resistance UK Deep Green Resistance advocates for the sabotage of infrastructure. Some nonviolent advocates discuss the use of sabotage in relation to nonviolence. In The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp does not classify the sabotage of property as violent, but states that sabotage could become violent if it causes injury or death. He considers that certain actions (including removal of key components, vehicle fuel, records or files) can fall somewhere between sabotage and nonviolent action. He describes that when nonviolent action has not been successful, sabotage has sometimes followed. Sharp does not describe any instances of sabotage being used by a disciplined nonviolent movement. In his view, sabotage is more closely related to violence than nonviolence, in terms of principles, strategy, and mechanisms of operation. [1]Sharp also lists nine reasons why sabotage will seriously weaken a nonviolent movement:

- it risks unintentional physical injury;

- it may result in the use of “violence” or the use of force against those who discover plans of sabotage;

- it requires secrecy in planning and carrying out missions, which also may result in “violence” or the use of force if discovered;

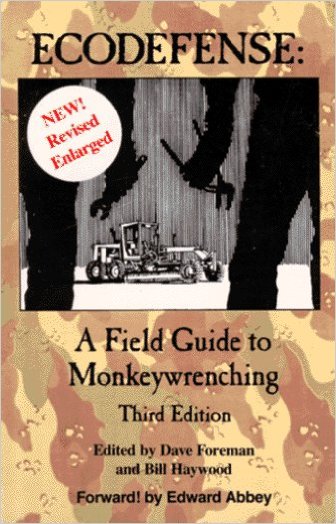

- it only requires a few resisters, which reduces large scale participation;

- it demonstrates a lack of confidence in nonviolent actions;

- it relies on physical destruction rather than people challenging each other directly;

- sabotage and nonviolence are rooted in very different strategies—nonviolence in withdrawal of consent, sabotage in destroying property;

- if any physical injury or death happens, even if by accident, it will result in a loss of support for the nonviolent cause;

- sabotage may cause increased repression. [2]

Ackerman and Kruegler agree with Sharp and recommend avoiding sabotage and demolition, but they do identify “nonviolent sabotage” as a form of economic subversion that renders resources for repression inoperative by removing components, overloading systems and jamming electronics. [3]Branagan differentiates nonviolent property damage and sabotage. Property damage that occurs during a nonviolent action may involve, for example, a hole in the road that has minimum impact, especially compared to ecological, structural, cultural or physical violence. In his model, sabotage is defined by conducting sustained systematic attacks on property, and then getting away with it. [4]  Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.To conclude this run of articles, over the last seven posts I’ve attempted to: define nonviolence and pacifism; explain what nonviolent resistance is; describe its advantages; signpost you to where you can learn more about struggles and who is advocating for nonviolent resistance; and finally how nonviolence and sabotage fit together.Pacifism is clearly based on good intentions and an understandable desire for a world at peace. Nonviolent resistance is a very important tactic in our struggle. But crucially, it can not be the only tactic if the movement for environmental and social justice ever hopes to be effective. If the planet is to remain livable in the medium term then the movement needs to determine which tactics are most likely to succeed. Regardless of the differences of opinion and focus within the movement, the movement as well as the planet are losing. Being wedded to mostly nonviolent tactics is a major cause of this failure.Strategic nonviolence has an important part to play in our resistance but the need for some nonviolent advocates to only advocate pacifism or nonviolent resistance in any circumstances and try to mandate it across whole movements, is counterproductive and causing the movement to be less effective.An act of sabotage or property destruction is violent or nonviolent depending on the intentions and the way they are carried out ( see post 4). I don’t think that sabotage or property destruction of nonliving things such as buildings, vehicles, and infrastructure in the defence of life can ever be considered violent.In the next run of posts I will explore the problems with nonviolence and pacifism. This is the eleventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more. Endnotes

Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.To conclude this run of articles, over the last seven posts I’ve attempted to: define nonviolence and pacifism; explain what nonviolent resistance is; describe its advantages; signpost you to where you can learn more about struggles and who is advocating for nonviolent resistance; and finally how nonviolence and sabotage fit together.Pacifism is clearly based on good intentions and an understandable desire for a world at peace. Nonviolent resistance is a very important tactic in our struggle. But crucially, it can not be the only tactic if the movement for environmental and social justice ever hopes to be effective. If the planet is to remain livable in the medium term then the movement needs to determine which tactics are most likely to succeed. Regardless of the differences of opinion and focus within the movement, the movement as well as the planet are losing. Being wedded to mostly nonviolent tactics is a major cause of this failure.Strategic nonviolence has an important part to play in our resistance but the need for some nonviolent advocates to only advocate pacifism or nonviolent resistance in any circumstances and try to mandate it across whole movements, is counterproductive and causing the movement to be less effective.An act of sabotage or property destruction is violent or nonviolent depending on the intentions and the way they are carried out ( see post 4). I don’t think that sabotage or property destruction of nonliving things such as buildings, vehicles, and infrastructure in the defence of life can ever be considered violent.In the next run of posts I will explore the problems with nonviolence and pacifism. This is the eleventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more. Endnotes

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 608/9

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, page 609/10

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993, page 39

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 124