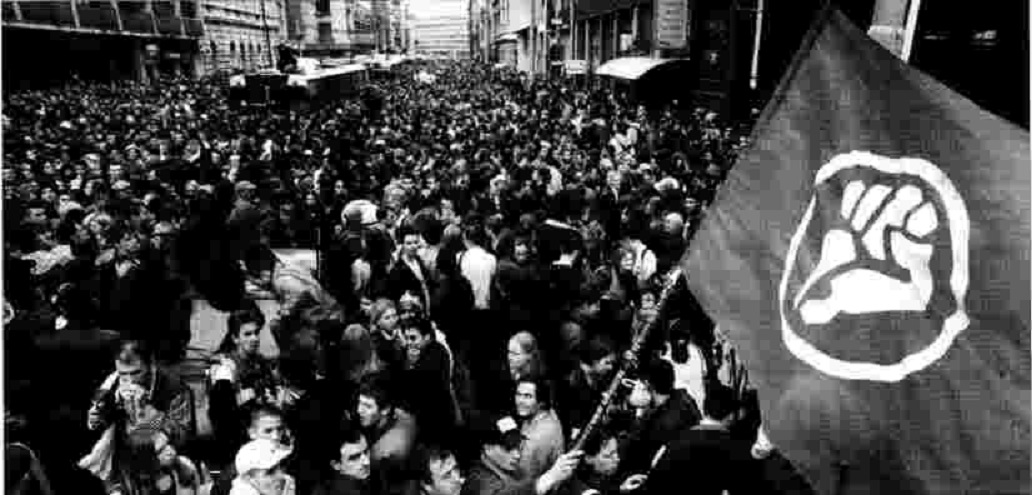

This is the eighth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more. via Deep Green Resistance UK Srdja Popovic, one of the organisers of Otpor, the nonviolent group that challenged Slobodon Milosevic in Serbia, now offers nonviolence training through the The Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS). Popovic views a nonviolent campaign as a war, but one which is fought with different kinds of weapons or sanctions. [1] He argues that a successful nonviolent struggle requires nonviolent discipline, unity, and planning. [2] He points out that the state employs fear and the threat of arrest or more terrifying repercussions to make the people obey:

All oppression relies on fear in order to be effective…the ultimate point of all this fear is not merely to make you afraid. A dictator isn’t interested in running a haunted house. Instead, he wants to make you obey. And when it comes down to it, whether or not you obey is always your choice. Let’s say that you wake up in some nightmare scenario out of a mafia movie, where some wacko tries to force you to dig a ditch. They put a gun to your head and threaten to kill you if you don’t start shoveling. Now, they certainly have the power to scare you, and it’s certainly not easy to argue with someone who has a pistol pointed right at your temple. But can anybody really make you do something? Nope. Only you can decide whether or not to dig that ditch. You are totally free to say no. The punishment will certainly be severe, but it’s still your choice to decline. And, if you absolutely refuse to pick up that shovel and they shoot you dead, you still haven’t dug them a ditch. So the point of oppression and fear isn’t to force you to do something against your will - which is impossible - but rather to make you obey. That’s where they get you. [3]

Popovic then explains that once those involved with Otpor moved past the fear of the unknown—and of being arrested—they were able to blunt the state’s oppressive power:

The best way to overcome the fear of the unknown is with knowledge. From the earliest days of Otpor!, one of the most effective tools the police had against us was the threat of arrest. Notice I didn’t say arrest but just the threat of it. The threat was much more effective than the thing itself, because before we actually started getting arrested by Milošević’s police, we didn’t know what jails were like, and because people are normally much more afraid of the unknown, we imagined Milošević’s prisons to be the worst kind of hell…But then when things started getting heated, a lot of us actually were arrested, and when we got back we told the others all about it. We left out none of the details. We wrote down and shared with our fellow revolutionaries every bit of what had happened in the jails. We wanted those about to get arrested themselves - we knew there were bound to be many, many more of us picked up by the dictator’s goons - to understand every step of what was going to happen to them. [4]

While this reasoning may not be appropriate in all socio-political contexts (such as for survivors of rape, assault, domestic abuse, and hate crime), it’s useful as a real world example of the power of knowledge in organizing a movement.He explains that in order for the average citizen to really engage with an issue, they need to believe something to be unfair or wrong. [5] Like Sharp, Popovic believes that “in a nonviolent struggle, the only weapon that you’re going to have is numbers.” [6] Nonviolent struggles try to win by converting people to the cause. Following this reasoning, Popovic advocates that a nonviolent campaign be relatable to arouse the sympathy of the masses. [7]Author Tim Gee writes in Counterpower: Making Change Happen, that power is “the ability for A to get B to do something that B would not otherwise have done,” and that “if the interests of those in power are not threatened…the likelihood of rulers voluntarily giving up power altogether is small.” [8] Gee proposes a strategic approach he calls “counterpower, which turns traditional notions of power on their head. Counterpower is the ability of B to remove the power of A.” The concept of counterpower involves challenging accepted truths or refusing to obey. Economic counterpower can be exercised through strikes and boycotts. Physical counterpower can mean fighting back or nonviolently utilizing human bodies to disrupt, stall, or permanently end the perpetration of injustices. [9] Gee goes on to describe four stages to a successful campaign: consciousness, coordination, confrontation, and consolidation. [10]Mike Ryan makes the astute observation in Pacifism as Pathology that writers from the 1800s did not state that nonviolence means the “absolute, constant and permanent absence of force or violence.” Doug Man’s “The Movement” and Pat James’ “Physical Resistance to Attack: The Pacifist’s Dilemma, the Feminist’s Hope” argue that it’s important to use the least forceful response that is appropriate to that situation, rather than not using force under any circumstances.If Man’s and James’ view on the acceptable level of violence were adopted by nonviolence movements today, then the ideological distance between nonviolent resisters and advocates of violent resistance would stem more from differences in analysis and choice of tactics, rather than the current focus on what’s moral or strategic. [11] This is the eighth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more. Endnotes

- Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanise Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World, Srdja Popovic, Matthew Miller, 2015, page 88

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 213

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 130

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 131

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 143

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 52

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 204

- Counterpower Why Movements Succeed and Fail, Gee, Tim, 2011, page 200

- Counterpower, page 13

- Counterpower, page 130

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 136

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org