by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 22, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I went up to Mauna Kea’s summit a few days ago to pule (to pray) with some of the protectors on a ridge inside the Thirty Meter Telescope’s (TMT) proposed construction site. When we reached the site, we were confronted by half a dozen large men in orange vests and hard hats brandishing cameras, audio recorders, and notebooks.

The boss told us we were trespassing on an active construction site and subject to arrest. I looked around and saw nothing but a handful of back-hoes, the open sky at 14,000 feet above sea level, and a sublime, obsidian-colored cinder field stretching to the clouds. Of course, as I’m writing this, construction on Mauna Kea has been suspended for more than two months.

Kaho’okahi Kanuha explained that we were simply here to say some prayers. The boss told us again we were subject to arrest, mumbled into a hand-held radio, signaled to his men, and began recording us with a camera. The six men took up positions surrounding us as we held hands and faced the sky with Kaho’okahi leading some chants. Some of the men folded large arms across their chests glaring at us, others recorded us on camera, and one circled us nervously. I’ve been in a few fist fights in my life – needless, pointless expressions of a toxic masculinity – and I felt like these men were revving themselves up for some sort of scrap.

It was impossible for me to pray like this. Kaho’okahi seemed completely unnerved and when I asked him about it, he said this happens every time he comes to pray. I remember my experiences in Mass when I was younger. I imagine a priest at the altar leading his parish in the prayers that, for Catholics, turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ – all while strong men in hard hats patrol the pews and record the liturgy.

This, of course, would never happen. So, I ask: When Kanaka Maoli pray on a mountain exceedingly more beautiful than any basilica or cathedral I’ve ever been in, why are they being harassed like this?

I spent the first six essays in this Protecting Mauna Kea series trying to answer this question. The answers I came up with are validated after spending the last two weeks up here. The TMT project is based on the dominant culture’s sense of entitlement, historical amnesia, and pornification of Hawaiian culture. What could resemble a porn shoot more closely than men with cameras intruding on and recording acts of intimacy?

I think I’ve demonstrated that the TMT project is enabled by a problematic worldview and should not be allowed to proceed. After Governor David Ige’s announcement last week that he would support and enforce the TMT’s construction, the Mauna Kea protectors want the world to know we never expected the State to help us. We must stop the TMT project and we must do it ourselves. The question becomes: “How do we do it?”

The occupation on Mauna Kea is an expression that the protection of Mauna Kea is the people’s responsibility. We cannot trust the government to stop the TMT. We cannot trust the police. We cannot trust the courts. We have to do it ourselves. In other words, nothing has changed since the occupation began over two months ago. In many ways, the occupation on Mauna Kea reflects all of our environmental and social justice movements around the world.

The truth is – on the whole – environmental and social justice movements around the world have been getting their asses kicked. If they weren’t, 200 species a day wouldn’t be going extinct around the world. If they weren’t, we wouldn’t be losing indigenous languages at a rate relatively faster than species. If they weren’t, 95% of North America’s old growth forests wouldn’t have been clear cut. If they weren’t, every mother around the world wouldn’t have dioxin – a known carcinogen – in her breast milk. And, why are they getting our asses kicked? One reason is we’ve trusted those in power to do the right thing for far too long. The good news is – while construction on the Mountain is suspended – we have the opportunity to avoid mistakes other movements have made.

**********************

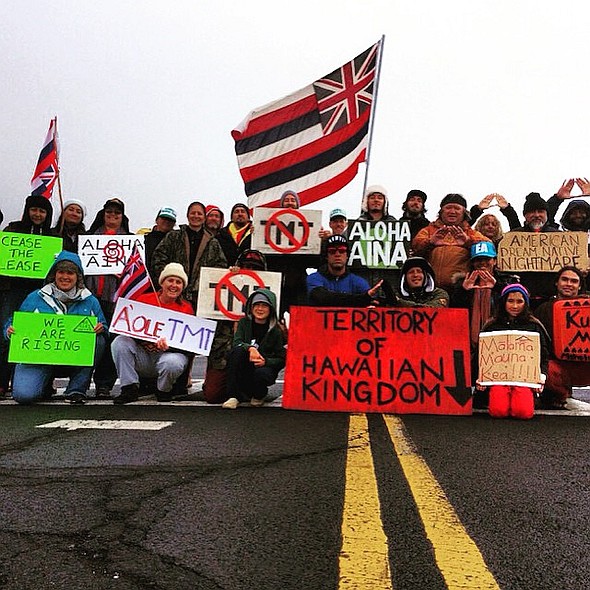

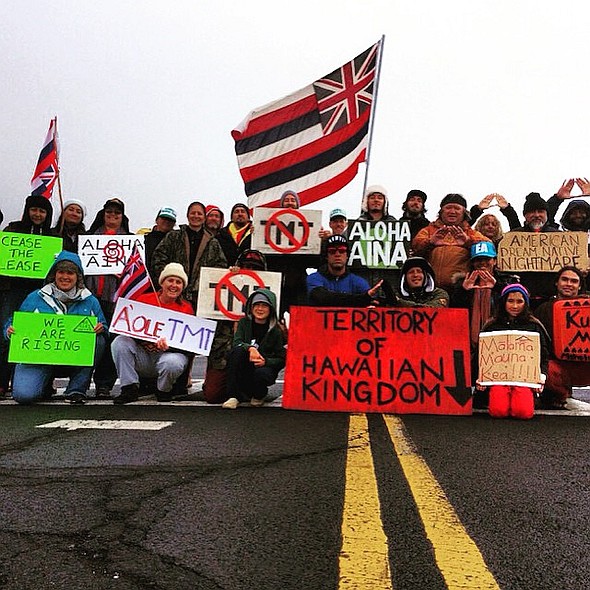

A couple days ago in a freezing cold, clinging mist, the Mauna Kea protectors called a 5:30 AM meeting in the now-famous crosswalk on the Mauna Kea Access Road to talk strategy in light of Governor Ige’s recent announcement. Some protectors lamented the announcement and were understandably scared about what was coming next. Others maintained that the TMT project was illegal anyway, and the courts would never let it proceed. Still others cited Kingdom of Hawai’i precedents and referred to the recent war crime charges filed with the Canadian government, to assure us the TMT was dead in the water. Finally. the boldest proudly proclaimed – with a hint of the false bravado that often accompanies anxious realizations – construction equipment would have to roll over their dead bodies to get to the construction site.

I stood silently in the circle listening. I am not Hawaiian and have no place arguing with those whose land I presently occupy. My mind was filling with memories of my experiences as a public defender. I recalled the cop in Kenosha, WI where I worked who put a gun to the temple of young Michael Bell’s head and murdered him as his mother and sister watched on for the crime of possibly breaking his bail conditions. I recalled that the cop was promoted and still on the force in Kenosha.

My stomach began churning as I felt that old feeling of helplessness sitting in a wooden chair in a courtroom next to another client being sentenced to prison while there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. There was no brilliant legal argument I could make, no impassioned plea the judge would listen to. The judge had power and armed men at his command, and I did not. It was as simple as that.

My heart was tugged back to Turtle Island, the so-called North American continent where the arrival of Europeans has meant the total extermination of dozens of aboriginal peoples. I think of the Taino who were annihilated within a few decades after Columbus’ contact with them. I can almost hear Tecumseh’s voice calling out from now-dead villages in present-day Ohio and Indiana asking what happened to the Pequods, the Narragansetts, and the Pocanokets. These peoples were wiped out by European colonizers while most of Tecumseh’s people, the Shawnee, were removed at gunpoint from their homelands in the Ohio valley hundreds of miles away to Oklahoma.

Some of the protectors here tease me, calling me “America’s ambassador to Hawai’i.” Listening to some of the protectors insist that the courts, the police, and the government would never let the TMT project happen, I wanted to explain that I understand the dominant culture we’re fighting against. I wanted to say I benefit from this culture. I was raised within in. I’ve lived amongst the type of people who run those courts, sit in their government, and become the police. I know what they are capable of and that many of them are sociopaths with no regard for the well-being of those who oppose them.

I didn’t say this, though, because I knew these feelings brought me too close to acting like the White Savior come to save aboriginal peoples from their ignorance. The truth is Kanaka Maoli understand very well – much better than I – the genocidal tendencies of the dominant culture occupying their lands. They do not need my reminder. I write about this now, only to narrate my relief when Kaho’okahi said, “I understand everyone’s concerns, but the way we’re going to win this struggle is pule plus action.”

**********************

Pule plus action. I agree with Kaho’okahi. Protecting Mauna Kea requires a strong spirituality, requires prayers, but it also means real, physical actions in the real, physical world. We need prayers, yes, just like we need those battling the TMT project in the courts, just like we need those signing petitions against the TMT project, just like we need those donating to the Mauna Kea protectors’ bail fund. But, at the end of the day, the surest way to stop the TMT project is to physically, actually stop the TMT project. This is what the encampment on Mauna Kea has always been about. The protectors are determined to place their bodies in between Mauna Kea’s summit and the construction equipment escorted by the police that will soon come to build the telescope.

I hope with all my heart that the courts will make the right decision and prohibit the TMT’s construction. I hope with all my heart that when the police receive their orders to pacify resistance on the Mountain that they will turn in their resignation papers. But, I’m not holding my breath. History has shown over and over again that the courts and the police will not help us.

Hope is not going to keep the destruction off Mauna Kea. It is much more likely that hope will bind us to ineffective strategies like trusting the government and hugging the police when they come to arrest us.

The Mauna Kea protectors insist on observing kapu aloha – a practice of love and respect – on the Mountain. I will not question this practice, but I will point out that our opponents do not observe kapu aloha. I fear that the more effective we become at stopping their project, the more violently they will respond.

I do not write this from a place of despair. I write this to give a clear-eyed vision of the effort it’s going to take. If we’re going to keep the TMT project from completion, we are going to have to do it ourselves. We’re going to have to show up in numbers large enough to overwhelm the police. We’re going to have to produce a mass of humanity thick enough to clog the Mauna Kea Access Road – and we may have to do it day in and day out for weeks. It will take a tremendous amount of bravery, shrewd strategic thinking, and a deep commitment from all of us. Or, in Kaho’okahi’s words, it’s going to take pule plus action. This is nothing new, though, and I believe we will win.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 21, 2015 | Listening to the Land

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I went to the Thirty Meter Telescope construction site near the summit of Mauna Kea for the first time, today. Four-wheel drive is recommended for the road that twists steeply with hairpin turns up the Mountain, so ten of us piled into a Kanaka uncle’s (older native Hawaiian man’s) pick-up truck to go see the summit. Leaving from the visitor center parking lot at 9,200 feet the road ascends over 5,000 feet to an elevation close to 14,000. While my ears popped, my sense of wonder grew. Conversations around the truck bed stopped as the Mountain’s power over our senses intensified.

Beginning below the tree line, the six-mile ride carries you through ancient cooled lava flows, across red-stained cinder fields, and under patches of snow adorning Mauna Kea’s brown shoulders like jewels. When we parked we took a moment to breathe the air that is thin, but crisp and fresh. The walking was hard. We moved slowly and I wondered if Mauna Kea keeps the air thin on purpose to ensure peace on the slopes. Serenity filled the spaces where the hills parted to show the clouds carpeting the valley floor below.

I felt like I was traveling in a timeless land until we turned a corner on the trail and the thirteen existing telescopes appeared on the ridge lines forming Mauna Kea’s summit. My breath caught and my stomach soured.

Some are calling the collection of observatories and assorted buildings the “industrial park on Mauna Kea” and I understand why. The telescopes themselves are housed in blank, white geodesic domes. Numerous support buildings including giant satellite radar dishes dot the slopes leading up to the telescopes. Roads – both paved and simply graded – lacerate the mountainside. Brown and orange outhouses stand like sores in otherwise breath-taking cinder fields. I recalled a picture I saw down at the visitor center showing one of Mauna Kea’s hills being dynamited before construction. Scars are still visible years later.

We did not linger long and left down the trail for Lake Waiau. There is no mistaking the sacredness of Lake Waiau. The Lake’s waters are an emerald green in the center rimmed in royal blue as the waters approach the Lake’s red cinder banks. I sat engulfed in the shimmering waves on the Lake’s surface. The wind is alive on Mauna Kea and it seemed to sense the enormity of the experience for me, dying down to allow me my stillness.

Then, two uncles in our party blew long, clear blasts on conch horns. The echoes rang through the intimate valley where Lake Waiau sits and filled my chest with warmth. I began to cry.

One of the uncles brought a harmonica and played some soft blues to the breeze. I kept crying. I cried for the destruction on Mauna Kea’s summit. I cried for the pain Kanakas expressed to me and to each other while talking story at the occupation. I cried for the pure joy of experiencing a power humans have felt for millennia and will continue to feel so long as we stop the destruction of the world’s sacred places.

****************

Back at the occupation, I reflect on my first trip to Mauna Kea’s summit. Ahinahina, named silverswords in English, are blooming on the slopes of Mauna Kea. The fragrance of their purple flowers sweeten the dry mountain air. Their silver stems glisten in the wind and shimmer with the sunshine. Above the ahinahina, the gold flowers of the mamane trees dance with delight to the day’s colors. I close my eyes in an effort to print these images onto my heart. I imagine what Mauna Kea must have looked like a couple hundred years ago when Kanaka Maoli – aboriginal Hawaiians – treated these slopes as sacred and forbidden to all but the most holy activities. No cattle were allowed here then. No invasive species choked out the ahinahina and mamane forcing endemic species to within inches of their existence. I imagine the mountain sides as they must have been: awash in silver and gold.

Silver and gold. I wince at the irony. That is, after all, what the Thirty Meter Telescope project is all about – pieces of silver and mounds of gold.

I open my eyes again, asking silently for the words ahinahina and mamane might want me to write. I wish I could ponder the beauty of these endangered plants forever. As I think this, standing in front of a ahinahina mesmerized by her elfin colors, a sparkle grows deep in her thin leaves and the comparison to the twinkle of stars Mauna Kea is famous for is undeniable.

****************

Of course, there are those saying the Thirty Meter Telescope project is about something more noble than money. I’ve heard, for example, it’s for “pure human curiosity,” or for “love for the stars.” The problem with this is not all human curiosities, nor all loves are created equal.

Where have we heard the human curiosity argument before? It is often used to excuse the actions of explorers that open the lands of original peoples to colonization. Christopher Columbus has his own holiday for “discovering America” while the total eradication of the Taino people is forgotten. Hitting closer to a Hawaiian home, Captain James Cook is honored for supposedly being the first European to land in Hawai’i.

And what has this cost Hawai’i? The population of Hawai’i in the late 1770s is estimated at more than one million people. By 1897 at the time of the Ku’e Petitions, only 40,000 Hawaiians survived. Over 95% of the Hawaiian people died in 120 years due to contact with Europeans. Of course, Cook knew this would happen as he warned his sailors not to engage in intercourse with Hawaiians.

Some will excuse Cook saying at least he tried to control his sailors. But, when we’re talking about the near total extinction of a whole culture, I think we need to judge with stronger standards. Who goes to work when they have a communicable disease like a cold? Who goes to work when they have a potentially fatal communicable disease? Who, among us, would willingly and knowingly expose our loved ones to danger? Cook did, and he did it, in part, out of “human curiosity.”

In response to the “love for the stars” argument, keep in mind that the Ku Klux Klan advertises itself as a “love group not a hate group.” Either we have to trust people like the KKK, or we realize that we cannot trust everyone’s rhetoric. Another way to look at this is to understand that often what is called “love” in this dominant culture is really a poisoned version of what love truly is. Those responsible for the TMT project might love the stars, but that love is poisoned by the destruction their project will create. What is love if it causes you to violate boundaries established by aboriginal peoples? What is love if it causes you to clear an 8 acre space, digging two stories on a formerly pristine mountain top? What is love if it causes you to dangerously perch hazardous chemical waste above the largest freshwater aquifer on Hawai’i Island?

Now, I am certainly not saying that love for stars is wrong. Every night up here on Mauna Kea, I roll out my sleeping bag under the open sky and gaze in awe at the stars. There is a right way and a wrong way to love the stars. Hawaiians who loved the stars so much they were able to navigate the largest ocean in the world with handmade canoes using the naked human eye loved the stars the right way, the least invasive way, the most respectful way. The TMT project with all of its destructive technology, all of the waste produced by the materials used in its construction like steel, aluminum, and mercury, is loving the stars the wrong way.

The counter to my argument is often, “You say you love the Mountain, but what good is a mountain?” Thankfully, the brilliant professor of ecology and leading figure in the deep ecology movement, Neil Evernden, has come up with the best response. He says the best way to respond to the questions, “What good is a mountain? What good is a ahinahina? What good is a mamane tree?” is to ask “What good are you?”

Evernden’s point is something I learned looking at Lake Waiau, is something I learned listening to the ahinahinas and mamanes. Mountains, ahinahinas, mamanes, polar bears, rhinoceroses, and you and I each exist for our own subjective purposes. Ahinahinas have lives, joys, dances, and purposes as valuable to them as ours are to us.

To take this idea even deeper, I know when I heard the clear notes of the conch horns above Lake Waiau I was sharing in a tradition thousands of years old. When the winds blew through my hair, the pores of the cinder rocks mixed with the pores of my skin, and the blue light on Lake Waiau was reflected in the blue light in my eyes, I was engaged in relationships that made me most fully human. To block those winds, to dynamite those cinder rocks, to poison the light from Lake Waiau, will destroy the relationships that make humans human. In other words, destroying Mauna Kea is destroying ourselves.

From San Diego Free Press

Find an index of Will Falk’s “Protecting Mauna Kea” essays, plus other resources, at:

Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i: Protect Mauna Kea from the Thirty Meter Telescope

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 22, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Listening to the Land

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Looking up at the still, lingering morning stars from the best stargazing location in the world early on the third day since my arrival at the occupation on Mauna Kea, my personal velocities catch up with me and I listen. I stand at 9,200 feet above sea level. North and above me, Mauna Kea’s shoulders broaden as they rise into the heavens. Down and to the east, a thick cover of clouds hides the valley below and deadens the rattle of rifle fire coming from the US military training center on the Mountain. Wind scatters the volcanic dust at my feet.

I have never been to a place like this, never looked down on the clouds from any where other than a plane seat, never marveled at the feel of lava pebbles in my palm and I wonder what it all means. Dawn’s thin air only offers my own reflections back to me.

I’ve been on the road for over a year now and the traveling leaves me feeling dizzy. After two suicide attempts, I decided to take tangible steps to alleviate my despair. A great part of my despair stemmed from the realization that life on Earth is running out of time. Even mainstream scientists are seriously questioning the ability of the human race to make it through the next half-century. Part of this destruction is rooted in the way the dominant culture has strayed too far from land-based, traditional knowledges. Traditional knowledges are often rooted in stories based on the land. So, one way to understand the destruction is to see how the dominant culture has forgotten the original stories the land is telling us.

My path out of despair has lead me all over this side of the world from the Unist’ot’en Camp on Wet’suwet’en territory in northern so-called British Columbia to Kumeyaay territory in so-called San Diego all the way across the ocean here to Hawai’i and Mauna Kea.

Moving at this pace, I sometimes feel profoundly lonely. Each new place means leaving friends behind and entering a social environment where no one knows who I am. My friends and family are scattered across North America. When I’d rather see my friends smile in person and hear their laughter transported over a breeze instead of the internet, I feel a deep sorrow. I know it is a self-imposed exile, but still, I yearn for home.

“Home” is something I do not have time for. The world is burning – our home is burning – and before I can rest comfortably in my home, I need to work to make sure that home does not burn down. Writing seems to be my talent, so I come to Mauna Kea persisting in my rejection of home, and offer up my pen.

Sitting down to write these first few days on Mauna Kea, to engage in the support I’ve promised, I’ve found that my migrations have an even deeper side effect: I struggle to relate to the places I’m in. New slants of sunshine are disorienting. New smells from a strange wind confuse me. I do not know the names of the birds I hear singing or the names of the trees who give me shade.

Writing is a spiritual practice for me that involves listening for the voices I know are speaking from the natural places I’m in. I’m finding it hard to understand what I am hearing here because I have not had enough time to develop relationships with the non-human beings living here on the Mountain. I have not heard enough of Hawaii’s history. I do not have the experiential referents to hear a story. I keep stumbling on the thought that I cannot possibly do this place justice in three days. Hawaiians have lived with Mauna Kea for time immemorial and already know what these other beings are saying.

Each time I try to describe a hill I’m looking at, the sound the sparse mountain trees make in the evening breeze, or the sight of the thin, new moon hanging low in the sky outside our tent, I sense much deeper stories at work. I feel incapable, unprepared, lost. I am not just seeing, hearing, and feeling these forces on a physical level. I sense these forces are working on a level deeper than I have the language to express.

How can I possibly write something comparable to the stories and wisdoms developed over millennia of listening by the original peoples who live here? Is English – a language developed in a land thousands of miles away – even adequate to the task? Or, am I struggling to articulate what I’m hearing because those voices are properly described in the Hawaiian language?

***

In these first three days, I have been showered in Hawaiian hospitality and my loneliness is alleviated. At the occupation, kapu aloha is thriving. I’ve spent most of my time “talking story” and I’ve learned just how potent Hawaiian traditional knowledges are. “Talking story” is a Hawaiian term meaning something similar to, but more than “chit-chat,” closer to “getting to know each other,” or “craic” in my own Irish tradition. Through talking story with the protectors here, I’ve heard about everything from the strategic military prowess of King Kamehameha I to the genius traditional navigational techniques of Hawaiian sailors to the high percentage of NFL players that come from Hawai’i.

Most importantly, though, I’ve been receiving an education in Hawaiian spirituality. I will not and cannot claim to know or understand very much of what has been shared with me. I’ve heard about the physical forms Hawaiian deities take – forms like snow, thunder, mist, and bamboo.

I’ve heard about Mauna Kea existing in both realms of the land and the sky and how traditionally humans were not supposed to travel very far up Mauna Kea. My experiences with death cause me to state that my favorite thing I’ve learned about Hawaiian spirituality, so far, is that every being that gives and facilitates life is a god revered for its role in supporting life.

Looking around me with my vision enhanced from the Mauna, I ponder life. The shallowness of my breath on the Mountain reminds me of those last moments before I lost consciousness each time I tried to kill myself. Both times I laid in what I thought would be my deathbed I was confronted with the shame knowing that suicide would prevent me forever from standing on the side of the living. Both times I saw the story of my life stretch out before me and knew I wanted the story to go on.

***

Last night while I was pondering my inability to write anything of substance, I experienced a series of significant events. First, while a few of us sat around talking story, the conversation turned to the Thirty Meter Telescope project. Stopping this project is, of course, why we’re here.

Many of the occupiers here are my age – I am 28 – and interestingly several of them were educated in Hawai’i’s first Hawaiian language immersion program. One of those who graduated from this program is a man named Kahookahi Kanuha, and I’ve heard him call the movement to protect Mauna Kea the most powerful Hawaiian movement since the resistance to American occupation in the 1890s. One of the reasons for the power of this movement, he explained, is that Hawaiians are getting their language back.

This fits what I understand about history. In my own Irish tradition, for example, the path to independence included a strong Gaelic language revival in the late 1890s with artists like William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory creating new, specifically Gaelic works, with Gaelic language schools springing up around the nation, and a new academic interest in what had been an illegal language.

I know, too, that one of the first things colonizers do is work to erase the colonized’s language.

This happened in Hawai’i in 1896 when the illegal Republic of Hawai’i forbade the use of the Hawaiian language in schools. Indigenous languages are so important to decolonization because as Haunani-Kay Trask writes in her diagnosis of colonization in Hawai’i, “From a Native Daughter,” “Thinking in one’s own cultural referents leads to conceptualizing in one’s own world view, which, in turn, leads to disagreement with and eventual opposition to the dominant ideology.”

Later that night, after I heard Kahookahi explain that the Hawaiian language revival is empowering his people, the director of Hawai’i’s Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) stopped by to talk story with the Mauna Kea protectors. In many respects, the DLNR’s interests are opposed to the Mauna Kea’s protectors, but he was invited in a spirit of dialogue and respect, and to his credit he visited (and brought us desert). During the course of the conversation, the director said, “There is fear in misunderstanding. And when you learn to understand, you learn not to fear.”

***

I am writing this Protecting Mauna Kea series, in part, to understand how it is possible for a culture to think it is acceptable to desecrate another people’s most sacred site by building a massive telescope on the top of a beautiful mountain. I want to understand what the individual humans responsible for this project think and feel. Are they simply mistaken about the nature of physical reality? Do they really think that digging deeply into a mountain to build a telescope will be harmless? What I have learned, so far on the Mountain, from the protectors, from Kahookahi, and from the director of the DLNR provide, perhaps, an answer.

Quite simply, when you understand a place is full of stories and the beings who provide these living stories, it becomes very difficult for you to destroy those stories. When you understand the language of a place and learn how to communicate in that place, it becomes very difficult for you to destroy that place. When you learn to talk story wherever you are, you can learn to understand, and fear becomes more difficult.

I think the TMT project is the result of a culture that has forgotten how to talk story, has forgotten the living stories unfolding everywhere around us. When you look at Mauna Kea and see a simple mountain – just a collection of earth as I’ve heard some insensitive folks describe it-you will treat it one way, but when you look at Mauna Kea and see, as traditional Hawaiians do, a vast collection of stories and living story-givers, you will treat it in a much different way.

Maybe the TMT project is a symptom of a culture moving too fast, governments spreading too far from the lands that created them, and peoples alienated from the homes of their ancestors?

Maybe the dominant culture is caught in the same problems I face in my travels? Moving with too high a velocity, it is confused, it is lonely, and instead of talking story with Mauna Kea, it seeks answers in the stars.

I have taken a great amount of comfort in the willingness of the Mauna Kea protectors to talk story with me. I am beginning to feel like I am making good friends. They are quick with inclusive stories and jokes. They are sharing the stories of Mauna Kea and my loneliness subsides.

All credit for this is due to the Mauna Kea Protectors.

I believe those controlling the TMT project have lost their stories and suffer a deep trauma because of this. They have forgotten that the land is the source of all meaning and feel justified destroying the land to build an attempt to find meaning on other planets. I think they would do well to truly talk story from a position of respect with the Mauna Kea Protectors. You never know what you’ll learn.

From San Diego Free Press

Find an index of Will Falk’s “Protecting Mauna Kea” essays, plus other resources, at:

Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i: Protect Mauna Kea from the Thirty Meter Telescope

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 17, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Pornography

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Trigger warning: This piece contains graphic descriptions of sexual and colonial violence.

Hatred is one of the most misunderstood processes at work in the world today. Cops are killing young people of color while simultaneously maintaining they’re not racists and do not hate the people they’re killing. A growing number of men watch pornography claiming they do not hate women. Millions of tourists visit Hawai’i annually – despite pleas from native Hawaiians to stop – and feel they are so far from hating Hawai’i, it’s their favorite place to visit.

While the real, physical world is burning at an ever faster pace, I could care less what those responsible feel in their hearts while they destroy. Maybe it’s true that a cop holds no hatred in his heart as he releases a flurry of bullets into another unarmed black person’s body. Maybe it’s true that a man feels no contempt as he orgasms to images of women being beaten in simulated rape scenes. Despite boarding giant fossil-fuel burning jets to see Hawai’i, despite supporting an invasive government responsible for genocide in order to keep Hawai’i’s borders open, despite paying money to industries that desecrate Hawaiian ancestors, maybe tourists to Hawai’i really do think they love the land they’re helping to destroy.

Then, again, maybe individual members of the dominant culture are more like the Nazi Eichmann who claimed no personal hatred for the Jews he was responsible for loading on cattle cars before they were exterminated in gas chambers.

Make no mistake, the dominant culture hates Hawai’i. If it didn’t, why is it killing species at a faster rate in Hawai’i than anywhere else in the world? If it didn’t, why is it dropping bombs on her islands? If it didn’t, why does it maintain an illegal occupation over the objections of her people?

What counts isn’t how a person feels, it’s what a person does. Settlers may feel an affinity for Hawaii, but when Hawaii is under attack as it has been for a century and a half, what counts is the material reality actions produce. When the planet’s life support systems are under attack, when, in other words, life itself is threatened to within inches of existence, material consequences are much more important than an emotional state.

***

In this Protecting Mauna Kea series, I want to encourage tangible support for native Hawaiian sovereignty in settler communities. In order to do that, I think it is necessary to understand the hatred expressed towards Hawai’i by the dominant American culture.

Before arriving in Hawai’i, I read and heard from several native Hawaiian scholars about the pornification of Hawaiian culture. I’ve learned right away how true this is. Just like men are conditioned to overlook hatred of women early in their lives through pornography’s propaganda, settlers are conditioned to hate Hawai’i through the pornification of Hawaiian culture.

I flew Hawaiian Airlines to Hawai’i, for example, and the complimentary in-flight snack included a candy called “Aloha-macs.” This product, by a company called “Hawaiian Host,” is self-labelled as “creamy milk chocolate covered macadamias – the original gift of aloha.” Hawaiian Host and the dominant culture seek to transform an ancient indigenous wisdom – aloha – into a candy, sugary trash, something to consume.

As soon as we boarded the plane, I noticed the video monitors displaying clips of beautiful, dancing Hawaiian women. I thought immediately of Haunani-Kay Trask’s brilliant essay “‘Lovely Hula Hands’: Corporate Tourism and the Prostitution of Hawaiian Culture” where she explains how tourism converts cultural attributes into pure profit.

Trask writes, “…a woman must be transformed to look like a prostitute – that is someone who is complicitous in her own commodification. Thus hula dancers wear clownlike makeup, don costumes from a mix of Polynesian cultures, and behave in a manner that is smutty and salacious rather than powerfully erotic. The distance between the smutty and the erotic is precisely the difference between Western culture and Hawaiian culture.”

Of course, before the pornification of Hawaiian culture the hula dance was a sacred expression. Again, Trask is enlightening, “In the hotel version of the hula, the sacredness of the dance has completely evaporated, while the athleticism and sexual expression have been packaged like ornaments. The purpose is entertainment for profit rather than a joyful and truly Hawaiian celebration of human and divine nature. The point, of course, is that everything in Hawai’i can be yours, that is, you the tourists’, the Non-Natives’, the visitors’.”

***

Pornography is an expression of hatred. A simple search of any popular porn website shows women being labelled “bitch,” “slut,” “cunt,” and “pussy.” Videos and images are arranged into categories like “blonde,” “brunette,” “Asian” on one end all the way down to “teens” “gang bangs” and “fisting” on the other end. “Fisting” involves inserting a fist or fists into vaginas and anal cavities. The production of pornography destroys the bodies of women, poisons truly mutual sexuality, and adds to a toxic masculinity that is killing the planet.

I know that many men will be angry with me for trashing their favorite pastime. I know, too, that many tourists will be angry with me for trashing their favorite fantasy. The truth is porn is killing our (men’s) sexuality and the tourist industry is killing the possibility that visitors will ever have a mutual relationship – free from oppression and subordination – with Hawaiians. Worse than this, however, pornography and the pornification of Hawaiian culture normalizes hatred and contributes to a violation imperative that is destroying Hawai’i along with indigenous lands around the world.

There are those who argue that porn is empowering for women, just like there are those who argue the tourism industry is empowering for Hawaiians. I do not believe this is true. This logic is the same logic that placed the phrase “Work will make you free” to greet prisoners over the gate at Auschwitz. No one – besides capitalists and coal mine owners – argues that coal mining is empowering to the miners. No one – besides capitalists and factory owners – argues that sweat shops empower sweat shop workers.

Proponents of porn and the tourism industry will say, “If porn and tourism are so bad, why do so many work in these industries?” But, when the war against women rages on, when native Hawaiians are still systematically dispossessed of their own homeland, survival often demands they take whatever work they can find. I can hold this position and hold no contempt for individuals working in the porn or tourist industry. I’m not interested in blaming individuals, but identifying root processes at work, so we can better work for the liberation of all.

***

I remember the first time I was shown pornography. I was ten. An older, male distant family member was flipping through the channels and stopped on an adult film. It was the first time I saw a naked adult female body – or, I guess I should say, mostly naked body. I remember clearly that she was dressed in a strange belt-like garment that wrapped around her breasts and opened over her vagina. Looking back, I understand the garment was clearly designed to highlight the only body parts valued in pornography.

My relative looked over and said, “Don’t tell your parents about this,” and continued watching.

The next time I was shown pornography was only a year or so later. I was at a family friend’s house and this time the person showing me porn was a boy only a few years older than me. Where in the first instance, all my ten-year-old eyes had seen was a highly sexualized representation of a woman’s body, in the second instance I saw the entire act of penetration. This was the first time I had ever seen or imagined sexual intercourse.

Speaking of hatred, I hate that my first experience with sexual intercourse of any kind was through a camera lens, showing a woman who couldn’t possibly have consented to my personal viewing of her, in a voyeuristic experience mediated by a patriarchal perspective. Even now, 17 years later, I remember the way the actor’s bodies were arranged. The woman was pushed over the armrest of a couch, splayed out, open for display while the man withheld every part of his body for contact except for his penis which was thrust forward. There was no love, no passion in the physical contact. The man never reached to embrace his partner. The two never kissed, never caressed each other, never even looked at each other.

The camera lens zoomed in to feature penetration. This, of course, was the whole point – penetration, invasion, domination. Or, to recycle Trask’s line and to apply it to porn, everything in a woman could be mine, a viewer’s, a man’s.

In those moments, my sexuality was poisoned. In each case, older males I knew and respected, showed me pornography. The question,”What does it mean to be a man?” was being answered with porn scenes. In sexual education classes in junior high school, these were the only references I had. In fact, pornography was shown to me a full ten years before I first had sex. Fantasy was imprinted in my mind well before reality ever had a chance.

This is happening to Hawai’i, too. Americans are bombarded with propaganda encouraging an entitlement to Hawai’i. Postcards with picturesque Hawaiian beaches are on refrigerators around the country while Americans fail to remember the atrocities committed to cripple Hawaiian resistance. Movies are made about Pearl Harbor glorifying the doomed bravery of white sailors while Americans forget the native Hawaiian dead who never consented to an American naval presence in the first place. Resorts are filled with American tourists while these tourists fail to consider the Hawaiian homeless those resorts created.

And now, in the latest effort to humiliate Hawaiian culture, corporations want to build a massive telescope on Mauna Kea. The connections to pornography are too clear to be overlooked. Mauna Kea – the most sacred place in Hawaii – is being penetrated, invaded, desecrated by the Thirty Meter Telescope project. The only way for proponents of the TMT to complete this project over the resistance in Hawai’i is to believe in the propaganda spread through the pornification of Hawai’i. To invade Mauna Kea is to demonstrate the belief that everything in Hawai’i is theirs, the scientists, the Non-Natives, the invaders.

The TMT is an expression of a hateful fantasy. They want to build a means to watch other planets far, far away while this planet is burning. They want to fantasize about homes light years away, when the home we love is being destroyed.

Of course, that’s really the point, isn’t it? They don’t love their home. They hate it. That’s why they want to build this telescope.

From San Diego Free Press

Find an index of Will Falk’s “Protecting Mauna Kea” essays, plus other resources, at:

Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i: Protect Mauna Kea from the Thirty Meter Telescope

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 5, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

When people have asked me why I am going to Hawai’i to help protect Mauna Kea and my answer involves words like “sacredness” or “spiritual,” I am surprised whenever I see the grimaces.

I often get an explanation like this, “I support indigenous people, of course, but the telescope is for science. Isn’t it a little…superstitious to block an astronomy project for a mountain?” I said I was surprised, but I shouldn’t be. Spirituality, I forgot, is anathema in many leftist circles.

It shouldn’t be.

I understand that many in this culture have been wounded by their experiences with religion. Some religions have, on the whole, been disasters for the living world. But, to write off all spirituality because of the actions of a few religions, is not just intellectually lazy and historically inaccurate, it erases the majority of human cultures that lived as true members acting in mutual relationship with their natural communities.

I am writing this article from occupied Ohlone territory in what is now called San Ramon, CA (in the Bay Area). According to the first European explorers who arrived here, this place was a paradise.

A French sea captain, la Perouse, wrote, for example, “There is not any country in the world which more abounds in fish and game of every description.” Flocks of geese, ducks, and other seabirds were so numerous that a gun shot would cause the birds to rise, “in a dense cloud with noise like that of a hurricane.”

In 250 years, with the arrival of Europeans and their spiritualities, we have gone from flocks of birds making noises like a hurricane to the concrete jungles many of us call “home.”

What was it about the Ohlone people that caused them to live in such balance with their natural community? Why didn’t the Ohlone people exhaust their land bases, over shoot the carrying capacity of their home, and colonize other lands like the Europeans who came with their crosses held high forcing the Ohlone to work and to die in the Missions? Only a racist could say, “Because they weren’t smart enough.”

Let me suggest that it was the Ohlone spirituality, the Ohlone way of relating to the world, that caused them to live the way they did. Of course, the Ohlone are just one of thousands of indigenous examples.

Right now, with the world on the verge of total collapse, wouldn’t we do well to respect the wisdoms developed by indigenous peoples who lived in balance with their land bases for thousands of years?

***

Those attempting to force the TMT project on Mauna Kea are products of a culture that has committed spiritual suicide. The dominant culture committed spiritual suicide when it adopted the belief that the land – as the physical source of all life – is not sacred.

Now, it attempts real suicide. I know because I did it, too. Twice.

The path to suicide begins with lies – lies like the notion that a mountain like Mauna Kea does not and cannot speak. As Derrick Jensen points out in A Language Older Than Words, the first thing they do in vivisection labs is cut the vocal cords of the animals they’re going to torture so they don’t have to hear the animals’ screams.

Now the dominant culture is cutting the vocal cords of the entire planet. Women are objectified so they may be raped, indigenous peoples are called savages so they may be massacred, and mountains are described as piles of matter so their tops may be chopped off, their guts ripped out in open pit mines, and massive telescopes built on their peaks.

The Sioux lawyer and author, Vine Deloria Jr., in his work God is Red, diagnosed our current environmental disaster as essentially a spiritual failure.

For Deloria, the Western notion that spirituality can be transported across space, time, and cultural context is a lie and leads to the spiritual emptiness that European settlers on this continent display.

Even worse, though, dominant Western spiritualities like Christianity demand that believers place their faith in a God existing somehow above and beyond the real, physical world. Instead of a belief in the land as the source of all life, an abstract, jealous, invisible, and largely incomprehensible male deity becomes the source of all life.

A hierarchy of beings is established with God on top, followed by angels, humans, animals comparable to humans evolutionarily, all the way down to plants, insect, and microbes. Mountains like Mauna Kea, in this view, are simple heaps of dirt. They may be pretty to look at, but nothing more.

My personal path to suicide reflects the cultural path to suicide Jensen and Deloria describe.

My family is devoutly Catholic. Before I turned 18 and left home, I can count the number of times I missed Mass on one hand. One of my grandmother’s favorite Christmas gifts was handmade, specially blessed rosaries. She says the rosary every morning. Scapulars hang from the rearview mirrors of cars family members drive. Of course, every doorway contains artistic renditions of Christ’s crucifixion.

I remember sometime in my early teens standing beneath a particularly brutal crucifix when I recognized the spiritual emptiness surrounding me. I looked at the crown of thorns piercing Christ’s forehead. I watched the blood running into his eyes. I winced at the spikes driven through his hands and feet. I knew that Christ’s femurs were broken by soldiers – mercifully, perhaps – so he could not use his legs to push up, open his lungs, and draw breath. I grew nauseous imagining Doubtful Thomas digging his hands into the lance wound under Christ’s rib cage.

Educated in Catholic grade schools, I knew the various explanations for Christ’s terrible death. He died to fulfill Old Testament prophesies. He died to redeem humanity. He died because he brought a revolutionary message of humility, poverty, and love. He died because he challenged the power of his Roman and Jewish rulers. He died, simply, to save the world.

I began to think about the spiritual practices in the Catholics I knew. I didn’t know anyone who was giving up much more than a percentage of their income to the Church much less putting their lives in danger to save the world.

When I asked myself how so many people could insist that Catholicism was the one, true faith while no one was willing to walk the same paths as Christ, the first cracks appeared in the wall of denial I called “faith.” Simply put, I looked around and couldn’t find any Christs.

As I grew up, the wall crumbled. The first time I masturbated I was convinced the Virgin Mary would appear to haunt me. The day after I lost my virginity, I went to Mass expecting to feel God biting me with guilt. All I could feel was joy that I could share such a wonderful feeling with a lover. I finally allowed myself to accept my disbelief and started asking questions. How could people professing love for the world propagate a message rooted in guilt, self-denial, and shame?

I became angry. I felt completely betrayed. I saw a world filled with spiritually dead people. The only people I knew speaking about spirituality were liars. So, I took my anger too far and decided that spirituality itself must be dead.

Giving up on spirituality, the world became a dead zone filled simply with material. Yes, I worked to ease human suffering. But, I only did this out of a strange sense of duty, out of the remnants of Catholic guilt that seeped so thoroughly into my soul that I knew no other way to function.

I hung on to this perspective for a few years, denying the voices singing around me, and essentially strangling my own spirituality to death. The dominant culture is cutting vocal cords and I stuffed my ears with despair. Perhaps, it was only logical – committing spiritual suicide as I did – that physical suicide came next.

***

The TMT project on Mauna Kea and others like it around the world are expressions of a culture determined to commit suicide. And I’m not talking about a metaphoric, cultural suicide. I’m talking real, physical suicide. I’m talking about the destruction of the planet’s life support systems.

How else do you explain storing a 5,000 gallon hazardous chemical waste container above the largest freshwater aquifer on Hawai’i Island like the TMT builders want to do?

To stop the TMT project, to stop the genocide of indigenous peoples, and to save the world, I believe we need to empower spiritualities that learned how to live in balance with their land bases. We need to empower indigenous spiritualities around the world.

Our predicament today is even more dire than in 1973 when Deloria wrote in God Is Red, “Ecologists project a world crisis of severe intensity within our lifetime…It is becoming increasingly apparent that we shall not have the benefits of this world for much longer. The imminent and expected destruction of the life cycle of world ecology can be prevented by a radical shift in outlook from our present naive conception of this world as a testing ground of abstract morality to a more mature view of the universe as a comprehensive matrix of life forms. Making this shift in viewpoint is essentially religious, not economic or political.”

I need to be absolutely clear before I write on: Personal spiritual transformation is not going to save us from anything, but our own personal despair. What we need are spiritual transformations on the cultural scale, but we’re not going to achieve these transformations when too many insist that spirituality is worthless.

Just like we will not recycle our way to the revolution, successfully petition Shell to stop murdering the Niger River Delta, or write a persuasive enough essay to convince those in power to stop the TMT project, personal spiritual transformation is too often a distraction from the need for physical action in the physical world.

I’ve written that no emotion – including despair – can kill you. You can kill you. You can put a gun to your temple, snort up a bottle of pills, or run the exhaust into your sealed-off car, and kill yourself. But, in each instance it will not be an emotional or a spiritual state that will kill you. It will be a physical action that kills you. This also means that it will take physical actions to bring you out of despair. This is as true on the cultural level as it is on the personal.

The dominant culture suffers from a profound sense of despair. It says that destruction is human nature. It says that greed is universal. It says that we already live in the best possible world and this world is violent, evil, and hateful. It would be one thing if the dominant culture was content to hold this despair in its heart, content to stay in bed all day with the paralyzing despair that many of us have felt.

The problem for life on this planet – the problem at Mauna Kea – is the dominant culture manifests its despair physically. Once the dominant culture isolated itself from the rest of life, it grew resentful. It became angry. And now it seeks a murder suicide. Left unchecked, it will kill everything and then turn the gun on itself.

In order to turn the spiritual tide we must protect places like Mauna Kea. If we lose the sacred, we won’t be far behind.

From San Diego Free Press

Find an index of Will Falk’s “Protecting Mauna Kea” essays, plus other resources, at:

Deep Green Resistance Hawai’i: Protect Mauna Kea from the Thirty Meter Telescope