Our first-in-the-nation lawsuit seeking personhood for the Colorado River was dismissed. After the Colorado Attorney General filed a motion to dismiss and threatened sanctions against attorney Jason Flores-Williams for the unforgivable act of requesting rights for nature, Flores-Williams withdrew our case.

When I agreed to serve as a next friend, or guardian, of the Colorado River, I saw the opportunity as a win-win. Either, we would win the lawsuit and the Colorado River would gain a powerful new legal tool to protect herself. Or, the lawsuit would be defeated proving that the American legal system privileges corporate rights to destroy the natural world over the natural world’s right to exist.

I knew it was highly unlikely that corporations, the courts, and the Colorado Attorney General would let rights of nature gain traction in American law. I wanted to be there, when the case failed, to remind everyone who invested hope in our cause that lawsuits are not the only way change is made.

I do not want this essay to come off like I am saying “I told you so.” I am heartbroken. A small part of me clung to the hope that Flores-Williams could resist the threats, that the Colorado Attorney General would, at least, litigate the case on the merits, and that the legal system would do the right thing. This hope, of course, was misguided.

***

Federal Building, Denver, Colorado (Photo: Deanna Meyer)

Several weeks ago, I wrote for the San Diego Free Press, “When has the American legal system been concerned with doing the right thing? While every ounce of my being hopes we win, if we lose, I want you to know why. I want you to be angry. And, I want you to possess an analysis that enables you to direct your anger at the proper targets.”

We lost because the American government and legal system are designed to ensure that corporations maintain the right to destroy nature for profit. We faced a centuries-old American legal tradition that defines nature as property. Property rights grant property owners the power to consume and destroy their property. The Colorado River is defined as property, and those who own her, possess the right to use her, extract her, destroy her – and they are. Because corporations also wield most of the world’s wealth, they have the most power to gain property rights over nature. Or, in other words, they have the most power to buy living non-human communities to turn them into dead, human products.

Making matters worse, the American legal system grants corporations the same rights as citizens. So, courts recognize corporate constitutional rights to free speech, protections from search and seizure, and guarantees to due process, equal protection, and reimbursement for lost future profits. One of the worst political ironies of our time is that abstract legal contraptions like corporations have rights, but the natural communities who give us life don’t.

It’s not just that corporations, and the courts and governments that protect them, will not let the rights of nature movement take hold; corporations cannot let the rights of nature take hold. They cannot let the rights of nature take hold because granting nature the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve would restrict corporate access to the natural world, which is the very source of corporate power.

Corporations gain their power by turning nature into commodities, which are then sold for profit. The more nature corporations can turn into commodities, the more profits they make. And, the more profits they make, the more nature corporations can turn into commodities. If this cycle does not stop, the planet’s life support systems will collapse.

In order to understand corporate dependence on the natural world, consider the five most powerful corporations according to this year’s Fortune 500 list: Walmart, Berkshire Hathaway, Apple, Exxon Mobil, and McKesson. Walmart, for example, depends on its ability to cheaply manufacture, distribute, and sell products as diverse as clothes, beauty items, toys, and food. To manufacture and distribute, a corporation must have access to raw materials to turn into products and must have access to energy to deliver those products. This is an abstract way of saying that Walmart must clear-cut (or pay someone to clearcut) living forests for wood, must rip-up (or pay someone to rip-up) living grasslands for agriculture, and must destroy (or pay someone to destroy) mountains and subterranean earth to extract oil for plastics, for the energy required to manufacture, and to power the planes, ships, and trucks that carry their products to markets around the world.

The same goes for Berkshire Hathaway who manages factory farms while running Dairy Queen, who burns massive amounts of fossil fuels while running BNSF Railway, who engages in one of the most destructive agricultural processes – cotton farming – while running Fruit of the Loom, and who perpetuates an ancient, bloody form of mining while running Helzberg Diamonds. Apple, similarly, could not produce iPods and iPhones without highly oppressive rare earth mining. McKesson could not create its pharmaceuticals without the highly toxic industrial processes that yield the necessary chemicals. Do we even need to talk about Exxon Mobil?

The rights of nature are diametrically opposed to corporate rights. Environmental philosopher John Livingston describes this opposition: “We sometimes forget that every time a court or a legislature – or even custom – confers or confirms a right in someone, someone else’s right is nibbled at: the right of women to equal employment opportunity is an infringement of the freedom of misogynist employers; the right to make a profit is at someone else’s cost; the right to run a motorcycle or a snowmobile reduces someone else’s right to peace and quiet in his own backyard; the rights of embryos impinge upon the rights of the women who carry them. And so on.”

Corporations cannot allow the Colorado River to possess rights because her rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve may trump their rights to destroy her for profit. This makes the rights of nature a dangerous idea.

***

Federal Building, Denver, Colorado (Photo: Deanna Meyer)

But, the natural world needs more than dangerous ideas.

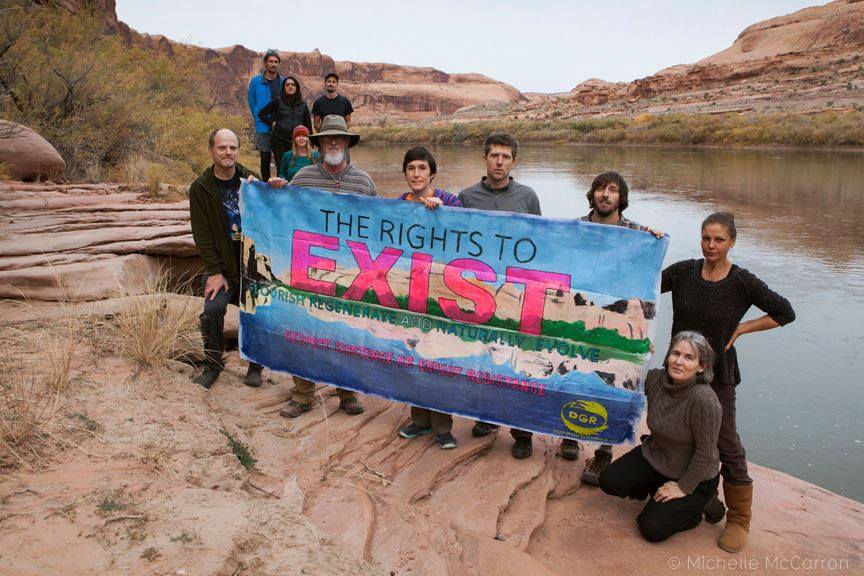

After we filed the lawsuit, I spent a month traveling with the Colorado River. As a “next friend” or guardian of the river, I agreed to represent her interests in court. To better understand her interests, I set out with the brilliant photographer Michelle McCarron to ask the river, “What do you need?”

I was naive to believe I could receive her answer in a month. After a month, I had only traveled the northern third of the river from her headwaters in La Poudre Pass, CO to just north of the Confluence where the Green River joins her in Canyonlands National Park. It wasn’t that she didn’t try to answer. She answered. And, her answer overwhelmed me.

In La Poudre Pass, standing in half a foot of snow in mid-October, she told me she needs snowpack and lamented that climate change causes less and less snow to fall. Near Grand Lake, where her waters are pumped through an industrial tunnel under Rocky Mountain National Park and across the Continental Divide, she showed me how theft is weakening her. In the orchards of Palisade, CO, where she is lacerated with ditches and canals to grow peaches and grapes, she begged to flow to willow thickets and marshes, instead, where she could grow birds and fish. Through the red rock near Moab, UT, where the wind sings in praise across the canyons the river has sculpted, she shuddered and whispered about the new, concrete walls that dam her path and that she cannot topple.

I will need much longer than a month to listen to everything the Colorado River needs. But, in all the time I spent listening, I did not hear her speak of a judge’s gavel, of evidentiary proceedings, or of the State of Colorado’s motion to dismiss. She cited no precedent, no binding legal authority, and no argument made by silver-tongued attorneys. She did not fear questions of jurisdiction or the threat of sanctions.

No, the Colorado River’s needs are real and physical. She needs snowpack. She needs a climate that facilitates her replenishment. She needs humans to stop manipulating her flows. She needs industry to stop wasting her waters on cash crops when wild beings are desperate for her. She needs dams to be removed.

We can give the Colorado River what she needs. We can stop burning fossil fuels. We can fill in the ditches and canals. We can let the desert reclaim the peach orchards and vineyards. We can, finally, remove dams.

Winning rights for the Colorado River would have helped, but they are not necessary. Better than the right to naturally evolve is naturally evolving. Better than the right to replenish is replenishing. Better than the right to exist is existing. And, better than the right to flourish is flourishing. Yes, it would have been a hell of a lot easier, if we could have gained a court order to remove dams along the Colorado River. But, court orders aren’t the only way dams fall.

When those who are supposed to protect us fail to do the right thing, we have to do it for them. There are recent examples of activists putting this principle into practice. On October 11, 2016, five climate activists (now famous as the “Valve Turners”) traveled to remote locations in North Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, and Washington state and turned shut-off valves on five pipelines carrying tar sands oil from Alberta, Canada into the United States. Elected officials would not shut down oil pipelines, so the Valve Turners did it for them.

Jessica Reznicek and Ruby Montoya, two brave women involved in Iowa’s Catholic Worker social justice movement, began a sabotage campaign against the Dakota Access Pipeline on Election Day 2016. Reznicek and Montoya burned heavy construction equipment, pierced steel pipes, and used oxyacetylene cutting torches to damage exposed empty pipeline valves. These actions delayed completion of the pipeline for weeks. Elected officials failed to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, so Reznicek and Montoya stopped it for them.

The brave actions of the Valve Turners and Reznicek and Montoya notwithstanding, most of us are engaged in tactics that leave it up to someone else to do the right thing. The dismissal of our lawsuit is one more failure in a long list of failures to recognize the power we do possess and to use that power to protect the natural world. We fail and Earth continues to heat up. We fail and human population continues to grow exponentially. We fail and the rate of species’ extinction intensifies. Each failure begs us to answer the question: Why do we still seek change through means that have never worked?