by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 8, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Weather Underground, 1969

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

The key problem with identifying successful strategies is that the context of historical resistance is different from the present. Their goals were often different as well. There’s a difference between destroying or expelling a foreign power, and forcing a power to negotiate or offer concessions, and dismantling a domestic system of power or economics. Such differences are the reason we’ve used relatively few anticolonial movements as case studies; their context and strategy are too different.

Resistance groups often fall prey to several major strategic failures. We’ll discuss five big ones here:

- A failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle.

- A failure to devise a consistent strategy and goal.

- An inappropriate excess of hope; ignoring the scope of the problem.

- A failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations.

- An unwillingness or inability to use the required tactics.

The first of these is a failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle. Yes, most resisters want to fight the good fight, and an out-and-out fight can be tempting. But that can only happen where resisters have superior forces on their side, which is almost never. The original IRA engaged in and lost pitched battles on more than one occasion.

In occupied Europe, writes M. R. D. Foot, “whenever there was a prospect that a large partisan force could be set up, people started asking for heavy weapons” instead of the submachine guns they were usually delivered. But artillery was always short on the front lines of conventional conflict, its presence drastically cut the mobility of a resistance group, and ammunition was hard to come by. “Bodies of resisters who clamoured for artillery were victims of the fallacy of the national redoubt … and of the old-fashioned idea that a soldier should stand and fight. The irregular soldier is usually much more use to his cause if he runs away, and fights in some other time and place of his own choosing.”16

Former Black Panthers have identified a similar problem with BPP strategy, specifically with their habit of equipping offices and houses to use as pseudofortresses. Explains Curtis Austin, “Using offices inside the ghetto as bases of operations was also a mistake. As a paramilitary organization, it should not have made defending clearly vulnerable offices a matter of policy. Sundiata Acoli echoed these sentiments when he noted this policy ‘sucked the BPP into taking the unwinnable position of making stationary defenses of BPP offices.… small military forces should never adopt as a general action the position of making stationary defences of offices, homes, buildings, etc.’ The frequency and quickness with which they were surrounded and attacked should have led them to develop a policy that would have allowed them to move from one headquarters to another with speed and stealth. Instead, the fledgling group constantly found itself defending sandbagged and otherwise well-fortified offices until their limited supplies of ammunition expired.”17

Early Weather Underground and SDS strategy similarly ignored the importance of surprise in planning actions by advertising and promoting open conflicts with the state and police in advance. This was criticized by other groups at the time. Writes Ron Jacobs, “From the Yippies’ vantage point, the idea of setting a date for a battle with the state was ridiculous: it provided the police with a greater capacity to counter-attack, and it also took away the element of surprise, the activists’ only advantage.… Pointing out the differences between the planned, offensive violence of Weatherman and Yippie’s spontaneous, defensive version, Abbie Hoffman termed Weatherman’s confrontations ‘Gandhian violence for the element of purging guilt through moral witness.’ ”18 (This analysis is interesting, if perhaps surprising and a little ironic, given the Yippies’ propensity for symbolic and theatrical actions.)

A most notable example of this problem was the “Days of Rage” gathering in Chicago in 1969. According to Weatherman John Jacobs, the intent of the Days of Rage was to confront the forces of the state and “shove the war down their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people.”19 Jacobs told the Black Panthers that 25,000 protesters would be present.20 However, only about 200 showed up, met by more than a 1,000 trained and well-equipped police. In a speech the day of the event, Jacobs changed tack and argued for the importance of fighting for righteous and moral (rather than tactical or strategic) reasons: “We’ll probably lose people today … We don’t really have to win here … just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory.”21 The protesters then started something of a riot, smashing some police cars and luxury businesses, but also miscellaneous cars, a barbershop, and the windows of lower- and middle-class homes22—not a great argument for superior strategy and tactics. The police quickly dispatched the protesters with tear gas, batons, and bullets. In the following days, almost 300 people were arrested, including most of the Weather Underground and SDS leadership. The Black Panthers—who were not afraid of political violence or of fighting the police—denounced the action as foolish and counterproductive. The Weather Underground, at least, did seem to learn from this when they went underground and used tactics better suited to an asymmetric conflict. (How effective their tactics were while underground is another question.)

All of this brings us to the second common strategic problem of resistance groups. Although their drive and values may be laudable—and although their revolutionary commitment is not in question—many resistance groups have simply failed to devise a consistent strategy and goal. In order for a strategy to be verifiably feasible, it has to have an endpoint that can be described as well as a clear and reasonable path or steps that connect the implementation of the strategy to the endpoint.

Some people call this the “A to B” factor. Does a proposed strategy actually lay out a reasonable path between point A and point B? If you can’t explain how the strategy might work or how you can implement it, you certainly can’t evaluate the strategy effectively.

It seems dead obvious when put in these terms, but a real A to B strategy is often missing in resistance groups. The problems may seem so insurmountable, the risk of group schisms so concerning, that many movements just stagger along, driven by a deep desire for justice and in some cases a need to fight back. But this leads to short-term, small-scale thinking, and soon the resisters can’t see the strategic forest for the tactical trees.

This problem is not a new one. M. R. D. Foot describes it in his writings about resistance against the Nazis in Occupied Europe. “Less well-trained clandestines were more liable to lose sight of their goal in the turmoil of subversive work, and to pursue whatever was most easy to do, and obviously exasperating to the enemy, without making sure where that most easy course would lead them.”23

It’s good and courageous to want to fight injustice, but resisters who only fight back on a piecemeal basis without a long-term strategy will lose. Often the question of real strategy doesn’t even enter into discussion. Jeremy Varon wrote in his book on the Weather Underground and the German Red Army Faction that “1960s radicals were driven by an apocalyptic impulse resting on a chain of assumptions: that the existing order was thoroughly corrupt and had to be destroyed; that its destruction would give birth to something radically new and better; and that the transcendent nature of this leap rendered the future a largely blank or unrepresentable utopia.”24 Certainly they were correct that the existing order was (and still is) thoroughly corrupt and deeply destructive. The idea that destroying it would inevitably lead to something better by conventional human standards is more slippery. But the main problem is the profound gap in terms of their strategy and objective. They had virtually no plan beyond their choice of tactics which, in the case of the Weather Underground, became largely symbolic in nature despite their use of explosives. Their uncritical “apocalyptic” beliefs about the nature of revolution—something shared by many other militant groups—almost guaranteed that they would fail to develop an effective long-term strategy, a problem to which we’ll return later on.

It’s very interesting—and hopefully illuminating—that a group like the Weather Underground did so many things right but completely fell down strategically. We keep coming back to them and criticizing them not because their actions were necessarily wrong, but because they were on the right track in so many ways. The internal organization of the Weather Underground as a clandestine group was highly developed and effective, for example. And their desire to bring the war home, their commitment to action, far surpassed that of most leftists agitating against the Vietnam War.

But as Varon observed, “The optimism of American and West German radicals about revolution was based in part on their reading of events, which seemed to portend dramatic change. They debated revolutionary strategy, and their activism in a general way suggested the nature of the liberated society to come. But they never specified how turmoil would lead to radical change, how they would actually seize power, or how they would reorganize politics, culture, and the economy after a revolution. Instead, they mostly rode a strong sense of outrage and an unelaborated faith that chaos bred crisis, and that from crisis a new society would emerge. In this way, they translated their belief that revolution was politically and morally necessary into the mistaken sense that revolution was therefore likely or even inevitable.”25

All of this brings us to a third common flaw in resistance strategy—an excess of hope. Obviously, we now know that a 1960s American revolution was far from inevitable. So why did the Weather Underground and others believe that it was? To some degree, this sort of anchorless optimism is a coping mechanism. Resistance groups are up against powerful foes, and believing that your desired victory is somehow inevitable can help morale. It can also be wrong. We should remember former prisoner of war James Stockdale’s “very important lesson”: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”26

Another factor is what you might call the bubble or silo effect. People tend to self-sort into groups of people they have something in common with. This can lead to activists being surrounded by people with similar beliefs, and even becoming socially isolated from those who don’t share their ideas. Eventually, groupthink occurs, and people start to believe that far more people share their perspective than actually do. It’s only a short step to feeling that vast change is imminent. This is especially true if the goal is nebulous and difficult to evaluate.

The false belief that “the revolution is nigh” is hardly limited to ’60s or leftist groups, of course. Even World War II German dissidents like Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, a conservative but anti-Nazi politician, fell prey to the same misapprehension. Writes Allen Dulles: “Despite Goerdeler’s realization of the Nazi peril, he greatly overestimated the strength of the relatively feeble forces in Germany which were opposing it. Optimistic by temperament, he was often led to believe that plans were realities, that good intentions were hard facts. As a revolutionary he was possibly naïve in putting too much confidence in the ability of others to act.”27

Significantly, but perhaps not surprisingly, his naïveté extended not just to potential resisters but even to Hitler. Prior to the July 20 plot, he firmly believed that if only he could sit down and meet with Hitler, he could rationally convince him to admit the error of his ways and to resign. His friends were barely able to stop him from trying on more than one occasion, which would have obviously been foolish and dangerous to the resistance because of their planned assassination.28 Of course, Nazi Germany was not just a big misunderstanding, and after the failed putsch, Goerdeler was arrested, tortured for months by the Gestapo, and then executed.

The fourth common strategic flaw is a failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations. We touched on this on a number of occasions in the organization section. Many groups—notably the Black Panthers—failed to implement an adequate firewall between the aboveground and underground. But we aren’t just talking about organizational partitions and separation; the history of resistance has showed again and again the larger strategic challenge of coordinating cooperative aboveground and underground action.

This has a lot to do with building mutual support and solidarity. The Weather Undeground in its early years was notably abysmal at this. Their attitude and rhetoric was aggressively militant. The organization, in the words of its own members (written after the fact), had a “tendency to consider only bombings or picking up the gun as revolutionary, with the glorification of the heavier the better,” an attitude which even alienated other armed revolutionary organizations like the BPP.29 Indeed, the Weather Underground would deliberately seek confrontation for the sake of confrontation even with people with whom it professed alignment. For example, in one action during the Vietnam War, Weather Underground members went to a working-class beach in Boston and erected a Vietcong flag, knowing that many on the beach had family in the US armed forces. When encircled, instead of discussing the war, they aggressively ratcheted up the tension, idealistically believing that after a brawl both sides could head over to the bar for a serious chat. Instead, the Weather Underground got their asses kicked.30

Now, there’s something to be said for pushing the limits of “legitimate” resistance. There’s something to be said for giving hesitant resisters a kick in the pants—or at least a good example—when they should be doing better. But that’s not what the Weather Underground did. In part the problem was their lack of a clear and articulable strategy. In his memoir, anarchist Michael Albert relates a story about being asked to attend an early Weather Underground action so that he could see what they do. “About ten of us, or thereabouts, piled into a subway car heading for the stop nearest a large dorm at Boston University. While in the subway, trundling along underground, one of the Weathermen, according to prearranged agreement, stood up on his seat to give a speech to his captive audience of other subway riders. He nervously yelled out ‘Country Sucks, Kick Ass,’ and promptly sat down. That was their entire case. It was their whole damn enchilada.”31 What are people supposed to get from that? By contrast, no one reading the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Plan would be confused about their strategy and goals.

But the Weather Underground’s most ineffective actions in the aboveground vs. underground department were those that actually harmed aboveground organizations. Their actions in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) are a prime example. SDS was a broad-based organization with wide support, which focused on participatory democracy, direct action, and nonviolent civil disobedience for civil rights and against the war. Before the formation of the Weather Underground, a group called the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), led by Bernardine Dohrn, later a leader of the Weather Underground, essentially hijacked SDS. They gained power at a 1969 national SDS convention and expelled members of a rival faction (the Progressive Labor Party and Worker Student Alliance). They hoped to push the entire organization into more militant action, but their coup caused a split in the organization, which rapidly disintegrated in the following years. In the decades since, no leftist student organization has managed to even approach the scale of SDS.

The bottom line is that RYM took a highly functional aboveground group and destroyed it. The Weather Underground’s exaltation of militancy got in the way of radical change and caused a permanent setback in popular leftist organizing. What the Weather Underground members failed to realize is that not everyone is going to participate in underground or armed resistance, and that everyone does not need to participate in those things. The civil rights and antiwar movements were appropriate places for actionists to try to build nonviolent mass movements, where very important work was being done, and SDS was a crucial group doing that work. Aboveground and underground groups need each other, and they must work in tandem, both organizationally and strategically. It’s a major strategic error for any faction—aboveground or underground—to dismiss the other half of their movement. To arrogantly destroy a functioning organization is even worse.

There is a fifth common strategic failure, which in some ways is the most important of them all: the unwillingness or inability to apply appropriate tactics to carry out the strategy. Is your resistance movement using its entire tool chest? A resistance movement that is fighting to win considers every operation and every tactic it can possibly employ. That doesn’t mean that it actually uses every tool or tactic. But nothing is simply dismissed without consideration.

The Weather Underground, to return again to their example, was a group which began with an earnest desire to fight back, to “bring the war home,” and express genuine solidarity with the people of Vietnam and other countries under American attack by taking up arms. Initially, this was meant to include attacks on human beings in key positions in the military-industrial complex. Indeed, before they went underground, as we’ve already discussed, the Weather Underground was eager to attack even low-level representatives of the state hierarchy, specifically police. Shortly after going underground, they changed their strategy.

The turning point in the Weather Underground’s strategy of violence versus nonviolence was the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion. In the spring of 1970, an underground cell there was building bombs in preparation for a planned attack on a social event for noncommissioned officers at a nearby army base. However, a bomb detonated prematurely in the basement, killing three people, injuring two others (who fled), and destroying the house. After the explosion, the Weather Underground took what you could call a nonviolent approach to bombings—they attacked symbols of power like the Pentagon and the Capitol building, but went out of their way to case the scenes before detonation to ensure that there were no human casualties.

Rather ironically, their post–Greenwich Village tactical approach again became largely symbolic and nonviolent, much like the aboveground groups they criticized. Lacking connections to other movements and organizations, and lacking a clear strategic goal, the Weather Underground’s efforts were doomed to be ineffective.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There’s one nagging thought that always returns to me when I’m studying WWII resistance strategy: resisters in Occupied Europe were brave, even heroic, but their actions alone did not bring down the Nazis. Resisters weakened the Nazis, hampered their actions, disrupted their logistics, and destroyed materiel. But they lacked the resources and organization to decisively engage and defeat Hitler’s forces. It took a conventional military assault by the Allies to finish the job. And the overwhelming majority of this was done by the Russians, with their large army relying heavily on infantry tactics. We can speculate about whether guerrilla uprisings in occupied countries would have eventually developed and ended Nazi rule, but that’s not what happened during the actual years of occupation.

For those of us who want to stop this culture from killing the planet, there are no capital “A” Allies with vast resources and armies. That’s the nature of our predicament. We may be able to ally ourselves with powers of lesser evil, the way that Spanish Anarchists allied themselves with Spanish Republicans and Soviets in Spain, or the way antebellum abolitionists allied themselves with Union Republicans against the Confederate South. But that will only get us so far, and joining the lesser evil can be dangerous.

How, then, would a successful resistance movement expand its actions beyond resistance that merely hampers to that which decisively dismantles civilization’s centralized systems of power, those that are allowing it to steal from the poor and destroy the planet? We’ll return to this in the Core Strategy chapter, but there are three main answers in terms of any theoretical deep green resistance movement’s “allies.” One is that the depletion of finite resources, along with the dead-ending of that pyramid scheme called industrial capitalism, will provoke a cascading industrial and economic collapse. Indeed, just during the time we’ve been writing this book, we’ve seen a banking crisis turn into a major credit crisis, which has cascaded into a recession and simmering global economic crisis. That disruption will undermine the ability of those in power to exercise their influence and concentrate wealth, and generally throw industrial civilization into a state of disarray.

A second answer is ecological and climate collapse. Cheap oil has so far insulated urban industrial people from most effects of increasing and catastrophic damage to the biosphere. But industrial collapse will mean the end of that insulation, and will mean that thousands of years of civilization’s “ecological debt” will come due. Furthermore, the earth is not just a passive battlefield—it’s alive, and it’s fighting on the side of the living.

A third, more tentative answer is that as all of this transpires, less overtly militant aboveground forces may fight against those in power out of self-interest. Once those in power no longer have the “energy slaves” offered by cheap oil and industry, they will (once again) increasingly try to extract that labor from human beings, from literal slaves. Hopefully people in the minority world, where the rich and powerful minority live, will have the good sense to see that and fight back against this enslavement, as so many people in the majority world, where the impoverished minority live, have already been doing for so long. But this is a more tenuous proposition. Popular resentment may be quick to build against a particular head of state or particular political party. Developing a mass culture of resistance against an entire economic or political system, however, can take decades. People who are privileged and entitled take a long time to change, if they change at all. More likely they will side with someone who makes big but ultimately empty promises.

Good strategy is part planning and part opportunity, and success depends on the effective use of both. In his book Guerrilla Strategies: An Historical Anthology, Gérard Chaliand suggests that the lessons of revolutionary warfare in the mid-twentieth century boil down to two key points. First, he writes, “The conditions for the insurrection must be as ripe as possible, the most favorable situation being one in which foreign domination or aggression makes it possible to mobilize broad support for a goal that is both social and national. Failing this, the ruling stratum should be in the middle of an acute political crisis and popular discontent should be both intense and wide ranging.” Second, he suggests, “The most important element in a guerrilla campaign is the underground political infrastructure, rooted in the population itself and coordinated by middle-ranking cadres. Such a structure is a prerequisite for growth and will provide the necessary recruits, information, and local logistics.”15

We’re clearly heading into a period of prolonged emergency, although the crisis will vary between chronic and acute over time. That increases the prospects for revolutionary—or rather, devolutionary—struggle, especially if radical organizations are able to anticipate and effectively seize opportunities offered by particular crises. It’s unlikely that mass support will be rallied for anticivilizational causes in the foreseeable future, because most people are happy to get the material benefits of this culture and ignore the consequences. However, an increase in political discontent can be beneficial even if it doesn’t create a majority.

Chaliand’s second conclusion is key, and even I find it a bit surprising that he would rank underground development so highly. But it makes sense; aboveground organizational infrastructure, though it may be hard work, is comparatively easy to expand. Underground infrastructure seems troublesome or irrelevant in times where resistance movements are too marginal or inactive to pose a threat. But as soon as they become successful enough to provoke significant repression, the underground becomes indispensible, and creating it at that point is extremely difficult.

The use of a crisis as an opportunity isn’t a new idea, but it has played a key role in strategic theory. Napoleon Bonaparte said that “the whole art of war consists of a well-reasoned and extremely circumspect defensive followed by rapid and audacious attack.” A similar opinion was shared by British strategist Basil Liddell Hart. As a foot soldier in World War I, Liddell Hart was injured in a gas attack and became horrified by the needless bloodshed. After the war he tried to develop strategy that would avoid the kind of carnage he’d been part of. In his book Strategy: The Indirect Approach (first published in 1941), he argued for a military strategy that has a lot in common with asymmetric strategy. Rather than attempting to carry out a direct assault on enemy military forces, he recommended making an indirect and unexpected attack on the adversary’s support systems, to decisively end the war and avoid prolonged and bloody battles.

Resisters can learn from this kind of approach. Often, because of the disorganized nature of many resistance movements, initial offensive actions are tentative and poorly coordinated. Sometimes these are celebrated because, well, at least they’re something. But they are rarely effective in and of themselves, and they may tip the hand of the resistance and allow those in power to seize the initiative.

When I’m looking for an analogy for civilization, I often think of the Borg from Star Trek. Relentlessly expansionist and essentially colonial, they insist that every indigenous culture they encounter “adapt to service” them—that every individual either assimilate to their basic imperative or die. Like any coercive hegemony, they insist that resistance is futile. They’re fundamentally industrial. They have overwhelming military force, and they’re very good at adapting to resistance. The good guys only get a few shots with their phasers before the Borg adapt, making the weapons virtually useless. Then the good guys have to rejig their tactics or run away until they have a better chance.

That’s basically what happens when a resistance group makes a token attack at the wrong time. If, instead of being “rapid and audacious,” an operation is slow and timid, the effect may be to point out the enemy’s weakness and allow them to shore it up. It removes the element of surprise. And that applies whether the resistance movement is using armed tactics, sabotage, or nonviolence.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 11, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

It’s also worth looking at the principles that guide strategic nonviolence. Effective nonviolent organizing is not a pacifist attempt to convince the state of the error of its ways, but a vigorous, aggressive application of force that uses a subset of tactics different from those of military engagements.

Gene Sharp recognized this, and Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler followed Sharp’s strategic tradition in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. They understand that there is no dividing line between “violent” and “nonviolent” tactics, but rather a continuum of action. Furthermore, they also understand the need for tactical flexibility; sticking to only one tactic, such as mass demonstrations, gives those in power a chance to anticipate and neutralize the resistance strategy. In terms of strategy, they argue “that most mass nonviolent conflicts to date have been largely improvised” and could greatly benefit from greater preparation and planning.5 I would argue that the same applies to any resistance movement, regardless of the particular tactics it employs.

Having assessed the history of nonviolent resistance strategy in the twentieth century, Ackerman and Kruegler offer twelve strategic principles “designed to address the major factors that contribute to success or failure” in nonviolent resistance movements. They class these as principles of development, principles of engagement, and principles of conception.

Their principles of development are as follows:

Formulate functional objectives. The first principle is clearly important in any resistance movement using any tactics. “All competent strategy derives from objectives that are well chosen, defined, and understood. Yet it is surprising how many groups in conflict fail to articulate their objectives in anything but the most abstract terms.”6

Ackerman and Kruegler also observe that “[m]ost people will struggle and sacrifice only for goals that are concrete enough to be reasonably attainable.” As such, if the ultimate strategic goal is something that would require a prolonged and ongoing effort, the strategy should be subdivided into multiple intermediate goals. These goals help the resistance movement to evaluate its own success, grow support and improve morale, and keep the movement on course in terms of its overall strategy. This is especially important when the dominant power structure has been in control for a long time (as opposed to a recent occupier). “The tendency to view the dominant power as omnipotent can best be undermined by a steady stream of modest, concrete achievements.”7 This is especially relevant to groups that have very large, ambitious goals like abolishing capitalism, ending racism, or bringing down civilization.

Develop organizational strength. Ackerman and Kruegler write that “to create new groups or turn preexisting groups and institutions into efficient fighting organizations” is a key task for strategists.8 They also note that the “operational corps”—who we’ve been calling cadres—have to organize themselves effectively to deal with threats to organizational strength, specifically “opportunists, free-riders, collaborators, misguided enthusiasts who break ranks with the dominant strategy, and would-be peacemakers who may press for premature accommodation.”9 These threats damage morale and undermine the effectiveness of the strategy.

Secure access to critical material resources. They identify two main reasons for setting up effective logistical systems: for physical survival and operations of the resisters, and to enable the resistance movement to disentangle itself from the dominant culture so that various noncooperation activities can be undertaken. “Thought should be given, at an early stage, to controlling sufficient reserves of essential materials to see the struggle through to a successful conclusion. While basic goods and services are used primarily for defensive purposes, such other assets as communications infrastructure and transportation equipment form the underpinnings of offensive operations.”10 In particular, they suggest stockpiling communications equipment.

Cultivate external assistance. The benefits of cultivating external assistance and allies should be clear. Combating an enemy with global power requires as many allies and as much solidarity as resisters can rally.

Expand the repertoire of sanctions. The fifth principle is key because it is highly transferable. By “expand the repertoire of sanctions,” they simply mean to expand the diversity of tactics the movement is capable of carrying out effectively. They also encourage strategists to evaluate the risk versus return of various tactics. “Some sanctions can be very inexpensive to wield or can operate at very low risk. Unfortunately, such sanctions may also have a correspondingly low impact. A minute of silence at work to display resolve is a case in point. Other sanctions are grand in design, costly, and replete with risk. They also may have the greatest impact.”11

Their second group of principles consists of principles of engagement:

Attack the opponents’ strategy for consolidating control. This is specifically intended for mass movements, but essentially the authors mean to undermine the control structure of those in power, to generally subvert them, and to ensure that any repression or coercion those in power attempt to carry out is made difficult and expensive by the resistance.

Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons. “The corps [or cadres] cannot prevent the adversaries’ deployment and use of violent methods, but it can implement a number of initiatives for muting their impact. We can see several ways of doing this: get out of harm’s way, take the sting out of the agents of violence, disable the weapons, prepare people for the worst effects of violence, and reduce the strategic importance of what may be lost to violence.”12 These options—mobility, the use of intelligence for maneuver, and so on—are basic resistance approaches to any attack by those in power, and not limited to nonviolent activists.

Alienate opponents from expected bases of support. Ackerman and Kruelger suggest using “political jiujitsu” so that the violent actions of those in power are used to undermine their support. Of course, we could extend this to generally undermining all kinds of support structures that those in power rely on—social, political, infrastructural, and so on.

Maintain nonviolent discipline. Interestingly, the key word in their discussion seems to be not “nonviolence,” but “discipline.” “Keeping nonviolent discipline is neither an arbitrary nor primarily a moralistic choice. It advances the conduct of strategy.”13 They compare this to soldiers in an army firing only when ordered to. Regardless of what tactics are used, it’s clear that they should be used only when appropriate in the larger strategy.

Their third and final group is the principles of conception:

Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making. Planning should be done on the basis of context and the big picture to identify the strategy and tactics used. Often, as we have discussed, this is simply not done. The failure to have a long-term operational plan with clear steps makes it impossible to measure success. “Lack of persistence, a major cause of failure in nonviolent conflict, is often the product of a short-term perspective.”14

Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of the protagonists. Strategists need to analyze and fluidly react to the changing tactical and strategic situation in order to shift to offensive or defensive postures as appropriate.

Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives. There must be a sensible continuum from the goals, to the strategy, to the tactics used.

There are clearly elements of this that are less appropriate for taking down civilization. For reasons we’ve already discussed—lack of numbers chief among them—a strategy of strict nonviolence isn’t going to succeed in stopping this culture from killing the planet. And there are many things about which I would disagree with Ackerman and Kruegler. But they aren’t dogmatic in their approach; they view the use of nonviolence (which for them includes sabotage) as a tactical and strategic measure rather than a purely moral or spiritual one. What I take away from their principles—and what I hope you’ll take away, too—is that effective strategy is guided by the same general principles regardless of the particular tactics it employs. Both require the aggressive use of a well-planned offensive. Strategy inevitably changes depending on the subset of tactics that are relevant and available, and a strategy that does not employ violent tactics is simply one example of that. The main strategic difference between resistance forces and military forces in history is not that military forces use violence and resistance forces don’t, but that military officers are trained to develop an effective strategy, while resistance forces too often simply stumble along toward a poorly defined objective.

How would a resistance movement expand from hampering to decisively dismantling industrial civilization’s systems of power? What can we learn from history?

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 27, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Despite the limitations created by their smaller numbers, resistance movements do have real strategic choices, from the loftiest overarching strategy to the most detailed tactical level. Let’s explore beyond the default palette of actions. Resisters can and must do far better than the strategy of the status quo.

There is a finite number of possible actions, and a finite amount of time, and resisters have finite resources. There are no perfect actions. Prevailing dogma puts the onus on dissenters to be “creative” enough to find a “win-win” solution that pleases those in power and those who disagree, that stops the destruction of the planet but permits the continuation of business as usual and lifestyles of conspicuous consumption. If resisters fall prey to this belief, if they accept its absurd and contradictory premises, they are engineering their own defeat before the fact. If resisters believe this, they are accepting all blame for the actions of those in power, accepting that the problems they face are theirfault for not being “innovative” enough, rather than the fault of those in power for deliberately destroying the world to enrich themselves.

At the highest strategic level, any resistance movement has several general templates from which to choose. It may choose a war of containment, in which it attempts to slow or stop the spread of the opponent. It may choose a war of disruption, in which it targets systems to undermine their power. It may choose a war of public opinion, by which to win the populace over to their side. But the main strategy of the left, and of associated movements, has been a kind of war of attrition, a war in which the strategists hope to win by slowly eroding away the personnel and supplies of the other side, thus wearing down the omnicidal power structures and public opposition to change more quickly than those forces can destroy our communities, more quickly than they can gobble up biodiversity, more quickly than they can burn the remaining fossil fuels. Of course, this strategy has been an abysmal failure.

A strategy of attrition only works when there is an indefinite amount of time to maneuver, to prolong or delay conflict. Obviously that’s not the case in the current situation, which is urgent and worsening. Furthermore, to achieve success in a war of attrition, the resistance must be able to wear down the enemy more quickly than it gets worn down; again, in the present case, those in power are not being worn down at all (except in the degree to which they are so rapidly consuming the commodities required for their own reign to continue).

Furthermore, a resistance movement fighting a war of attrition must reasonably expect that it will be in a better strategic position in the future than it is at the current time. But who genuinely believes that we—however you would define “we”—are moving toward a better strategic position? And in order to get ahead in a war of attrition, resisters would have to have more disposable resources than their opponent.

Another crucial element in a war of attrition is reliable recruitment and growth. It doesn’t matter how many enemy bridges a group takes out if the adversary can build them faster than they can be destroyed. And on every level, civilization is recruiting and growing faster than resistance forces. To keep pace, resistance fighters would have to destroy dams more quickly than they are built, get people to hate capitalism faster than children are inculcated to love it, and so on. So far, at least, that’s not happening.

Of course, we are not in a two-sided war of attrition. Those in power aren’t holding back, but have been actively attacking. And those in the resistance haven’t even been fighting a comprehensive war of attrition; it’s more like a moral war of attrition. Rather than trying to erode the material basis of power, we’ve been hoping that eventually they’ll run out of bad things to do, and perhaps then they’ll come around to our way of thinking.

A movement that wanted to win would be smarter and more strategic than that. It would abandon the strategy of moral attrition. It would identify the most vulnerable targets those in power possess. It would strike directly and decisively at their infrastructure—physical, economic, political—and do it while there is still a planet left.

Strategy and tactics form a continuum; there’s no clear dividing line between them. So the tactics available, which will be discussed in the next chapter, Tactics and Targets, guide strategy, and vice versa. But strategy forms the base. If resistance action is a tree, the tactics are spreading branches and leaves, finely divided and numerous, while the strategy is the trunk, providing stability, cohesion, and rootedness. If resisters ignore the necessity and value of strategy, as many would-be resistance groups do—they are all tactics, no strategy—then they don’t have a tree, they have loose branches, tumbleweeds blowing this way and that with changing winds.

Conceptually, strategy is simple. First understand the context: where are we, what are our problems? Then, develop the goal(s): where do we want to be? Identify the priorities. Now figure out what actions are needed to get from point A to point B. Finally, identify the resources, people, and specific operations needed to carry out those activities.

Here’s an example. Let’s say you love salmon. Here’s the context: salmon have been all but wiped out in North America, because of dams, industrial logging, industrial fishing, industrial agriculture, the murder of the oceans, and global warming. The goal is for the salmon population not only to stop declining, but to increase. The difference between a world in which salmon are being wiped out, and one in which they are thriving, comes down to those six obstacles. Overcoming them would be the priority in any successful strategy to save the salmon.

What actions must be taken to honor this priority? Remove the dams. Stop industrial forms of logging, fishing, and agriculture. Stop the massive production and dumping of plastics. Stop global warming, which means stop the burning of fossil fuels. In all these cases, existing structures and practices have to be demolished for salmon to survive, for the goal to be accomplished.4

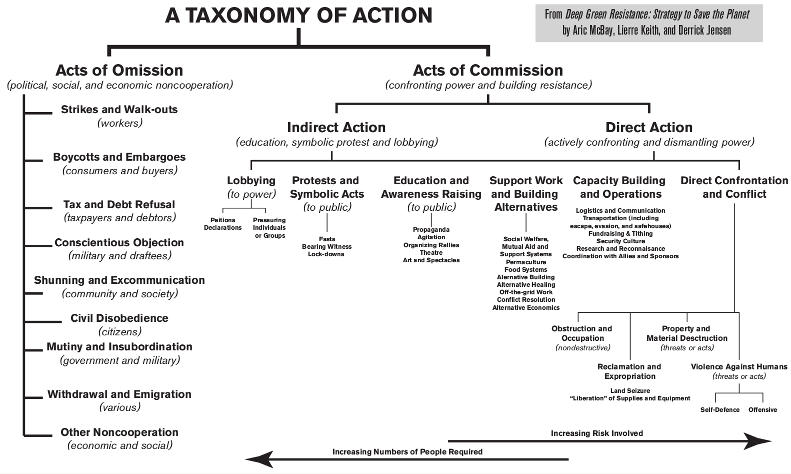

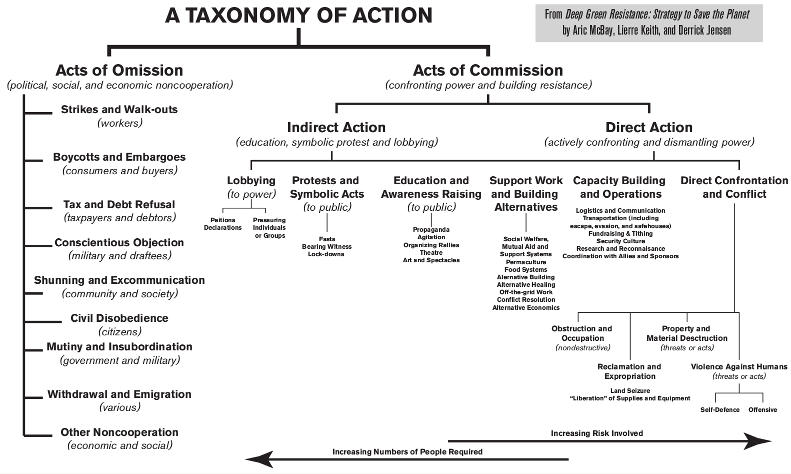

Now it’s time to proceed to the operational and tactical side of this strategy. According to the US Army field manual, all operations fit into one of three “all encompassing” categories: decisive, sustaining, or shaping.

Decisive operations “are those that directly accomplish the task” or objective at hand. In our salmon example, a decisive operation might be taking out a dam or preventing a clear-cut above a salmon spawning stream. Decisive operations are the centerpiece of strategy.

Sustaining operations “are operations at any echelon that enable shaping and decisive operations” by offering direct support to those other operations. These supporting operations might include funding or logistical support, communications, security, or other aid and services. In the salmon example, this might mean providing transportation to people taking out a dam, bringing food to tree-sitters, or helping to research timber sale appeals. It might mean running an escape line or safehouse, or providing prisoner support.

Shaping operations “create and preserve conditions for the success of the decisive operation.” They alter the circumstances of the conflict and help bring about the conditions required for victory. Shaping operations could include carrying out a campaign on the importance of removing dams, undermining a particular logging company, or helping to develop a culture of resistance that values effective action and refuses to collaborate. However, shaping operations are not necessarily broad-based or indirect. If an allied underground cell were to attack a nearby pipeline as a distraction, allowing the main group to take out a dam, that diversionary measure would be considered a shaping operation. The lobby effort that created the Clean Water Act could even be considered a shaping operation, because it helps to preserve the conditions necessary for victory.

If you review the taxonomy of action chart, you’ll see that the actions on the left consist mostly of shaping operations, the actions along the center-right consist mostly of sustaining operations, and the right-most actions are generally decisive.

Click for larger image

These categories are used for a reason. Every effective operation—and hence every effective tactic—must fall into one or more of these categories. It must do one of those things. If it doesn’t—if that operation’s or tactic’s contribution to the end goal is undefined or inexpressible—then successful resisters don’t waste time on that tactic.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 15, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

I do not wish to kill nor to be killed, but I can foresee circumstances in which both these things would be by me unavoidable. We preserve the so-called peace of our community by deeds of petty violence every day. Look at the policeman’s billy and handcuffs! Look at the jail! Look at the gallows! Look at the chaplain of the regiment! We are hoping only to live safely on the outskirts of this provisional army. So we defend ourselves and our hen-roosts, and maintain slavery.

—Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown”

Anarchist Michael Albert, in his memoir Remembering Tomorrow: From SDS to Life after Capitalism, writes, “In seeking social change, one of the biggest problems I have encountered is that activists have been insufficiently strategic.” While it’s true, he notes, that various progressive movements “did just sometimes enact bad strategy,” in his experience they “often had no strategy at all.”1

It would be an understatement to say that this inheritance is a huge problem for resistance groups. There are plenty of possible ways to explain it. Because we sometimes don’t articulate a clear strategy because we’re outnumbered and overrun with crises or immediate emergencies, so that we can never focus on long-term planning. Or because our groups are fractured, and devising a strategy requires a level of practical agreement that we can’t muster. Or it can be because we’re not fighting to win. Or because many of us don’t understand the difference between a strategy and a goal or a wish. Or because we don’t teach ourselves and others to think in strategic terms. Or because people are acting like dissidents instead of resisters. Or because our so-called strategy often boils down to asking someone else to do something for us. Or because we’re just not trying hard enough.

One major reason that resistance strategy is underdeveloped is because thinkers and planners who do articulate strategies are often attacked for doing so. People can always find something to disagree with. That’s especially true when any one strategy is expected to solve all problems or address all causes claimed by progressives. If a movement depends more on ideological purity than it does on accomplishments, it’s easy for internal sectarian arguments to take priority over getting things done. It’s easier to attack resistance strategists in a burst of horizontal hostility than it is to get things together and attack those in power.

The good news is that we can learn from a few resistance groups with successful and well-articulated strategies. The study of strategy itself has been extensive for centuries. The fundamentals of strategy are foundational for military officers, as they must be for resistance cadres and leaders.

PRINCIPLES OF WAR AND STRATEGY

The US Army’s field manual entitled Operations introduces nine “Principles of War.” The authors emphasize that these are “not a checklist” and do not apply the same way in every situation. Instead, they are characteristic of successful operations and, when used in the study of historical conflicts, are “powerful tools for analysis.” The nine “core concepts” are:

Objective. “Direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective.” A clear goal is a prerequisite to selecting a strategy. It is also something that many resistance groups lack. The second and third requirements—that the objective be both decisive and attainable—are worth underlining. A decisive objective is one that will have a clear impact on the larger strategy and struggle. There is no point in going after one of questionable or little value. And, obviously, the objective itself must be attainable, because otherwise efforts toward that operation objective are a waste of time, energy, and risk.

Offensive. “Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.” To seize the initiative is to determine the course of battle, the place, and the nature of conflict. To give up or lose the initiative is to allow the enemy to determine those things. Too often resistance groups, especially those based on lobbying or demands, give up the initiative to those in power. Seizing the initiative positions the fight on our terms, forcing them to react to us. Operations that seize the initiative are typically offensive in nature.

Mass. “Concentrate the effects of combat power at the decisive place and time.” Where the field manual says “combat power,” we can say “force” more generally. When Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest summed up his military theory as “get there first with the most,” this is what he was talking about. We must engage those in power where we are strong and they are weak. We must strike when we have overwhelming force, and maneuver instead of engaging when we are outmatched. We have limited numbers and limited force, so we have to use that when and where it will be most effective.

Economy of Force. “Allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts.” In order to achieve superiority of force in decisive operations, it’s usually necessary to divert people and resources from less urgent or decisive operations. Economy of force requires that all personnel are performing important tasks, regardless of whether they are engaged in decisive operations or not.

Maneuver. “Place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power.” This hinges on mobility and flexibility, which are essential for asymmetric conflict. The fewer a group’s numbers, the more mobile and agile it must be. This may mean concentrating forces, it may mean dispersing them, it may mean moving them, or it may mean hiding them. This is necessary to keep the enemy off balance and make that group’s actions unpredictable.

Unity of Command. “For every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander.” This is where some streams of anarchist culture come up against millennia of strategic advice. We’ve already discussed this under decision making and elsewhere, but it’s worth repeating. No strategy can be implemented by consensus under dangerous or emergency circumstances. Participatory decision making is not compatible with high-risk or urgent operations. That’s why the anarchist columns in the Spanish Civil War had officers even though they despised rulers. A group may arrive at a strategy by any decision-making method it desires, but when it comes to implementation, a hierarchy is required to undertake more serious action.

Security. “Never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage.” When fighting in a panopticon, this principle becomes even more important. Security is a cornerstone of strategy as well as of organization.

Surprise. “Strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which they are unprepared.” This is key to asymmetric conflict—and again, not especially compatible with a open or participatory decision-making structures. Resistance movements are almost always outnumbered, which means they have to use surprise and swiftness to strike and accomplish their objective before those in power can marshal an overpowering response.

Simplicity. “Prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding.” The plan must be clear and direct so that everyone understands it. The simpler a plan is, the more reliably it can be implemented by multiple cooperating groups.

In fact, these strategic principles might as well come from a different dimension as far as most (liberal) protest actions are concerned. That’s because the military strategist has the same broad objective as the radical strategist: to use the decisive application of force to accomplish a task. Neither strategist is under the illusion that the opponent is going to correct a “mistake” if this enemy gets enough information or that success can occur by simple persuasion without the backing of political force. Furthermore, both are able to clearly identify their enemy. If you identify with those in power, you’ll never be able to fight back. An oppositional culture has an identity that is distinct from that of those in power; this is a defining element of cultures of resistance. Without a clear knowledge of who your adversary is, you either end up fighting everyone (in classic horizontal hostility) or no one, and, in either case, your struggle cannot succeed.

In the US Army’s field manual on guerrilla warfare, entitled Special Forces Operations, the authors go further than the general principles of war to kindly describe the specific properties of successful asymmetric conflict. “Combat operations of guerilla forces”—and, I would add, resistance and asymmetric forces in general—“take on certain characteristics that must be understood.”2 Six key characteristics must be in place for resistance operations:

Planning. “Careful and detailed.… [p]lans provide for the attack of selected targets and subsequent operations designed to exploit the advantage gained.… Additionally, alternate targets are designated to allow subordinate units a degree of flexibility in taking advantage of sudden changes in the tactical situation.” In other words, it is important to employ maneuvering and flexible application of combat power. It’s important to emphasize that planning is notabout coming up with a concrete or complex scheme. The point is to plan well enough that they have the flexibility to improvise. It might sound counterintuitive, but the goal is to create an adaptable plan that offers many possibilities for effective action that can be applied on the fly.

Intelligence. “The basis of planning is accurate and up-to-date intelligence. Prior to initiating combat operations, a detailed intelligence collection effort is made in the projected objective area. This effort supplements the regular flow of intelligence.” That’s strategic and operational intelligence. On a tactical level, “provisions are made for keeping the target or objective area under surveillance up to the time of attack.”

Decentralized Execution. “Guerrilla combat operations feature centralized planning and decentralized execution.” It is necessary to have a coherent plan, and in order for that plan to be a surprise, the details often have to be kept secret. A centralized plan allows separate cells to carry out their work independently but still accomplish something through coordination and building toward long-term objectives. Decentralized execution is needed to reach multiple targets for a group that lacks a command and control hierarchy.

Surprise. “Attacks are executed at unexpected times and places. Set patterns of action are avoided. Maximum advantage is gained by attacking enemy weaknesses.” When planning a militant action, resisters don’t announce when or where. The point is not to make a statement, but to make a decisive material impact on systems of power. This can again be enhanced by coordination between multiple cells. “Surprise may also be enhanced by the conduct of concurrent diversionary activities.”

Short Duration Action. “Usually, combat operations of guerrilla forces are marked by action of short duration against the target followed by a rapid withdrawal of the attacking force. Prolonged combat action from fixed positions is avoided.” Resistance groups don’t have the numbers or logistics for sustained or pitched battles. If they try to draw out an engagement in one place, those in power can mobilize overwhelming force against them. So underground resistance groups appear, accomplish their objectives swiftly, and then disappear again.

Multiple Attacks. “Another characteristic of guerrilla combat operations is the employment of multiple attacks over a wide area by small units tailored to the individual missions.” Again, coordination is required. “Such action tends to deceive the enemy as to the actual location of guerrilla bases, causes him to over-estimate guerrilla strength and forces him to disperse his rear area security and counter guerrilla efforts.” That is, when those in power don’t know where an attack will come, they must spend effort to defend every single potential target—whether that means guarding them, increasing insurance costs, or closing down vulnerable installations. And as forces become more dispersed in order to guard sprawling and vulnerable infrastructure, they become less concentrated and correspondingly make easier targets.

Other writers on resistance struggles have shared these understandings. Che Guevara outlined similar strategy and tactics in his book Guerilla Warfare (1961), which itself followed from Mao Tse-Tung’s 1937 book on the subject. Colin Gubbins, former head of the British Special Operations Executive, wrote two pamphlets on the subject for use in Occupied Europe (written not long after Mao’s book). These pamphlets—The Partisan Leader’s Handbook and The Art of Guerilla Warfare—were based in part on what the British learned from T. E. Lawrence, but also from their attempts to quash resistance warfare in Ireland, Palestine, and elsewhere. In The Partisan Leader’s Handbook, Gubbins touched on the elements of surprise (“the most important thing in everything you undertake”), mobility, secrecy, and careful planning. “The whole object of this type of warfare is to strike the enemy, and disappear completely leaving no trace; and then to strike somewhere else and vanish again. By these means the enemy will never know where the next blow is coming,” he wrote.

Gubbins also urged resisters to “never engage in any operation unless you think success is certain.” Small resistance units don’t have the numbers or morale to absorb unnecessary losses. Resistance groups should only engage the enemy at points and times where they can overwhelm. The first step to take before any action is to plan a safe line of retreat, and “break off the action as soon as it becomes too risky to continue.” A newly founded resistance group often lacks the experience and training to accurately gauge how risky a situation is, which is why Gubbins recommends erring on the side of caution. It is better to learn iteratively and build up from a number of small successes than to get caught attempting operations that are too large and apt to end in failure. The takeaway message: successful resistance movements choose their battles carefully.

Just as asymmetric strategies require specific characteristics for success, they also have definite limitations.3 Resistance forces typically have “limited capabilities for static defensive or holding operations.” They often want to hold territory, to stand and fight. But when they try, it usually gets them killed, unless they’ve spent years developing extensive social and military groundwork and have a large force and popular support. Another limitation is that, especially in the beginning, resistance forces lack “formal training, equipment, weapons, and supplies” that would allow them to undertake large-scale operations. This can be gradually remedied through ongoing recruitment and training, good logistics, and the security and caution required to limit losses through attrition; however, resistance forces are often dependent on local supporters and auxiliaries—and perhaps an outside sponsoring power—for their supplies and equipment. If they can’t find those supporters, they will probably lose.

Communications offer another set of limitations. Communications in underground groups are often difficult, limited, and slow. This also applies to organizational command; the more decentralized an organization is, the longer it takes to propagate decisions, orders, and other information. And because resistance groups have small numbers and finite resources, “the entire project is dependent upon precise, timely, and accurate intelligence.”