by DGR News Service | May 28, 2020 | The Solution: Resistance

This is the text of a handout being distributed at ongoing DGR solidarity and mutual aid actions.

We can’t depend on the government or corporations to provide for our communities.

That’s why Deep Green Resistance, in coordination with our allies is responding with community MUTUAL AID. We are building local food systems and autonomy by distributing food and other basic necessities, seeds, small livestock, cooking and gardening supplies, native tree seedlings (98% of old growth forest in the U.S. has been destroyed), first-aid resources, and self-sufficiency education to people in the community.

Why Mutual Aid?

As the recent crisis show, modern industrial civilization is fragile. Globalized supply chains are highly vulnerable to global disruptions. And capitalism has systematically destroyed alternatives. Most of us don’t own land, so we must buy what we need to survive.

More of these shocks are coming, as industrial civilization destroys the ecological foundations of life. Soil and water depletion, deforestation, ocean acidification, the rise of dead zones, and overfishing are just a few of the trends.

We are seeing cracks in the industrial food system, which is leading people to question modernity. This is a good thing. It’s essential that we begin a wholesale shift away from high-energy, consumeristic lifestyles and towards local, small-scale, low-energy ways of life. We need to abandon industrial capitalism before it destroys all life on the planet.

“There is no sovereignty without food sovereignty.” — John Mohawk

What is Your Political Platform?

Deep Green Resistance is a revolutionary organization. We are opposed to racism, sexism, and colonization, and in our analysis industrial civilization is destroying the ecology of this planet. We advocate, agitate, and organize to dismantle industrial civilization and replace it with localized, sustainable human communities.

Not only do we need to re-localize our food systems, we also need community defense and resistance movements dedicated to pro-actively dismantling industrial civilization in solidarity with colonized peoples and indigenous communities. We can’t just grow nice gardens. We have to get organized, fight like hell against the ruling class, and bring a revolutionary edge to all of our organizing. We have to combine building the new with dismantling the old.

The failure of mainstream political parties of technological solutions are becoming increasingly clear to average people. They are looking for solutions. Popular movements are becoming increasingly confrontational. But still, it is rare that anyone is able to articulate a feasible alternative to the dominant culture, the techno-industrial economic system.

A political resistance movement has this alternative. By coordinating allies and simultaneously working to rapidly re-localize and de-industrialize human populations, we provide a feasible alternative to partisan gridlock and demonstrate a tangible real-world alternative. This movement needs to begin at the local and regional levels, seizing power in schools, county offices, water and soil boards, and building our own power structures through localized food networks, housing, labor, and political organizing.

How Can I Get Involved?

Mutual aid must be mutual. We are looking to build and strengthen long-lasting relationships of trust and solidarity, and find new allies. Community building is a key goal for us in this effort. We will continue to organize mutual aid efforts, pressure governments to allocate land for community garden, and take direct action.

We hope to see this project replicated around the world. We take inspiration from the many people already engaged in this sort of work, especially combining ecological awareness, practical re-localization, and revolutionary resistance. Contact us for more information, to get involved, or to talk about implementing similar projects in your community.

Resources

- https://retrosuburbia.com/ — an online book on how to be self-sufficient.

- https://selfsufficientme.com — videos and information on home food production.

- Charles Dowding provides many videos on getting started on vegetable growing.

- There are plenty of good-quality videos on YouTube to help you start a vegetable garden, keep chickens, design a food forest, establish urban farming, and make compost.

- https://www.milkwood.net/ —resources on growing, foraging and community care.

- To prep for power outages, build a simple, cheap rocket stove to cook on (YouTube).

- Look into local community gardens, permaculture and organic growing groups, and neighborhood centers for information that is relevant to your neighborhood.

* We have chosen to distribute native oak seedlings because native oak savanna is the most endangered habitat in the country. More than 95% of it has been destroyed since colonization. Second, because acorns can be a valuable staple food. Third, because planting native oak trees (and assisting in the northward migration of valuable non-native food trees) can help begin the transition to perennial food systems while both mitigating and preparing for global warming and biodiversity collapses (oaks are prized by wildlife and oak savanna is an extremely biodiverse habitat).

by DGR News Service | May 27, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This excerpt is from Derrick Jensen’s unpublished book “The Politics of Violation.” It is part 2 in a series. Part 1 can be found here. The piece discusses the difference between what has been called lifestyle anarchism and social anarchism.

The excerpt has been edited slightly for publication here. The book is in need of a publisher. Please contact us if you wish to speak with Derrick about this.

By Derrick Jensen

A Matter of Perception

Just today I was talking with a friend about an economist who says that contrary to the fable commonly presented by boosters of capitalism, currency didn’t evolve to facilitate barter exchanges; members of functioning communities don’t generally barter, but rather participate in gift economies and the building of social capital. Instead, currency was created in the autocratic regimes of ancient Egypt and Sumer to facilitate taxation and debt peonage (a form of slavery).

My friend interrupted me to say, “Oh, of course. Currency exists for the same reason governments exist: to facilitate commerce, and to shift more power to the already powerful.”

So he’s an anarchist, right?

Not on your life. He can’t stand anarchists, because too many of them, he says, don’t believe in rules. “How can you have a community without standards? It’s ridiculous to think you can, and ridiculous to think that even if you could, anyone else would want to put up with your bad behavior.”

Whether his perception of anarchism is accurate isn’t the point. The point is the prevalence of this perception, and the reasons for this prevalence.

My Introduction to Anarchism

The first time I encountered anarchist literature, in my twenties, I was new to the understanding that states are inherently oppressive and set up primarily to serve the governors, and I was excited to learn more about this political theory called anarchism. I went into an anarchist bookstore, and asked for a recommendation from the black-haired, black-bearded man behind the counter. He pointed me toward a small anarchist ‘zine, which he said would be a great introduction. I bought it, took it home, and started to read.

I quickly became disgusted: the ‘zine contained all sorts of transgressive horrors. In one story the author admired someone getting a job at a mortuary so he could “cornhole” (as he put it) the dead people. I remember thinking, “The anarchist at the bookstore thought a ‘zine promoting necrophilia was a good introduction to anarchism?” I threw the ‘zine into the recycling bin. This experience was so revolting it kept me from reading any books on the history of anarchism, many of which are very good, for several years.[1]

How many other possible recruits have been driven away by these aspects of anarchism? Perhaps equally important, what sorts of people would not be driven away by these aspects? What sorts of people would find this an inviting entry to a political philosophy? Would you want to share a movement with them?

Easier Said than Done

I have a friend who has been a radical, revolutionary activist for twenty-five years. He’s not a fan of anarchism. When I told him I was writing a book about this war in anarchism between those who simply believe governments primarily serve the powerful and those who oppose any constraints on their own behavior, he urged me on.

I asked him why he disliked anarchists so much.

He said, “When I first became politically aware, in college, I became fascinated by anarchism. It was obvious, from reading Chomsky and others, that the United States is an imperial power, and that a primary purpose of the state is to provide both rationale and muscle for economic exploitation. From my reading it seemed that anarchism stands in opposition to that. So I joined an anarchist book group. That was fine for a few months, but then I wanted to do something besides argue about books. I wanted to figure out what issues were most important to me, organize campaigns around those issues, and begin the real work of social change.

“That’s when the problems began. So long as we didn’t do anything but argue about theory, the anarchists were fine. As soon as I started trying to accomplish something in the real world, the anarchists refused to help. I soon realized these anarchists were more interested in arguing than in creating social change. And sadly, with only a few absolutely wonderful exceptions, this has continued to be my experience of anarchists.”

This particular activist has been fortunate in that those anarchists merely refused to help. While I, too, know some wonderful anarchists who are reliable friends and comrades, I also know a lot of people who will no longer work with anarchists because so many anarchists have actively sabotaged their campaigns, using: malicious gossip and other disinformation; physical destruction of campaign materials; rushing the stage and stealing microphones; de-platforming, assaulting, or shouting down those who deviate from anarchist ideology and identity; and co-opting the activists’ work away from the original intent and toward the anarchists’ own ends. For many activists, attempting to organize with—or even interact with—anarchists has been a complete nightmare.

Misogyny

While at dinner with an activist friend, I asked her what’s wrong with anarchism. She said, “Misogyny. By nature I should be an anarchist. I fully recognize the oppressiveness of the state. And I want to be an anarchist. But it’s so completely saturated with misogyny that I can’t do it. It’s not even that anarchism has misogynistic tendencies. It is misogyny.”

I asked her if I could use her name in the book. She said she would prefer I not, because every time she has publicly critiqued anarchism for its misogyny, she has received routine rape and death threats.

Today I spoke with an extremely well known anarchist, who is a decent person—one of the “few absolutely wonderful exceptions” my activist friend mentioned, and certainly to my mind one of the anarchists fighting on the right side of the struggle for the direction of anarchism. He doesn’t perpetrate or promote the sorts of community-destroying behavior I describe in this book.

He told me he believes that anarchism, while flawed, is worth saving.

“I see a few problems with anarchism,” he said. “The first is that it’s a very small movement, and so while there will be nutters in any movement, in anarchism their influence on both the movement and public perception of the movement will be magnified. I’m sure there are complete nutters in the Democratic and Republican Parties, and in the Sierra Club, and for that matter among stamp collectors and chess players. But anarchism is much smaller, which makes the obnoxious outliers all that more obvious.

“The next problem is that there are some strains of anarchism—and I’m thinking of anarchoprimitivism and other extreme forms of libertarian (as opposed to communitarian) anarchism—that encourage community-destroying behavior. These strains will draw an even more disproportionate percentage of nutters, and will cultivate them, to the detriment of all, and to the detriment of anarchism as a whole.

“The third problem is that anarchism is perceived by many as a self-definition: Someone becomes an anarchist by simply deciding he or she is an anarchist. This means that among a lot of self-declared anarchists, anarchism can mean whatever they want it to mean, which means it doesn’t really mean anything at all. I don’t agree with this, and I don’t believe that a lot of people who call themselves anarchists actually are. I believe anarchism has a very specific meaning, and has a long tradition of resistance to empire, a long tradition of working for communities, and I don’t want to give up on that tradition just because a bunch of nutters are causing problems.

“But there we run into another problem with anarchism, which is that it’s an open membership, by which I mean there really isn’t a process by which we can kick people out who are harming others, and who are harming anarchism. And any anarchist who does try to get the nutters to behave is immediately labeled a fascist or worse. This is a terrible problem in anarchism, and one we need to resolve.”

Raison d’être

To work toward solving that problem is one reason I wrote this book.

[1] I’ve often wondered if the recommendation was this anarchist’s terrible idea of a joke: “Let’s freak out the newbie!” But even if it was, that leaves two questions: Why did the bookstore even carry a ‘zine promoting necrophilia, and, why did the bookstore allow this person anywhere near the public?

DGR is guided by a Code of Conduct and a Statement of Principles. We believe it is necessary for an organization to adhere to principles and codes in order to keep our movement organized.

by DGR News Service | May 26, 2020 | The Problem: Civilization

In this piece, Salonika explains how this culture prioritizes economic gains over human and natural welfare. She describes how series of toxic accidents in India (of which the Vishakhapatnam gas leak is one example) lays testimony to this fact. In such a culture, is it possible to hold the responsible actors accountable for their actions?

Vishakhapatnam Gas Leak: Who do We Hold Accountable?

By Salonika

On 7th of May, 2020, a gas leak on the outskirts of Vishakhapatman (R. R. Venkatapuram village) has killed 12 people, including 2 children, and injured 1000 others. Vishakhapatnam is one of the largest cities of Andhra Pradesh, the eastern state of India.

LG Polymers, along with other similarly damaging industries, were established in the outskirts of Vishakhapatnam in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. Within the five decades since then, urbanization has moved the city nearer to the industries.

Many fled their homes in the middle of the night. Some were fortunate enough to reach a place of safety, while others fell unconscious on the streets. At least 3 of the deaths were due to people falling unconscious under unfortunate situations: two people crashed a bike while fleeing the area; one woman fell off her window. Many more were found unconscious on their beds.

The gas, Styrene, caused itchiness in the eyes, drowsiness, light-headedness, and breathlessness. In severe cases, the gas causes irregular heartbeats, coma or death. A district health official stated that the long-term health effects of this accident is yet unknown.

The gas leaked from an LG Polymers plant around 2:30 AM, and spread around a 3 km (2 miles) radius. Workers reportedly failed to alert the local residents after they found out about the leak. The police were informed around 3:30 AM, and went to the scene, but had to retreat for fear of being poisoned.

It took hours before the situation could be stabilised. LG Polymers did not have any mechanisms in place to prepare for emergencies like this. This led the local youth, local police and personnel from National Disaster Response Force to act as first-respondents.

Who caused the leak?

Speculations have arisen suggesting that chemical reactions occurred during the lockdown in the plant due to inactivity, clogging the cooling systems, which caused the tanks to heat up eventually causing a leak. No inhibitors were found on the plant to slow the process in cases of emergency. The leak occurred after the operations on the plant restarted following the lockdown was eased in India.

LG Polymers (a South-Korean company) stated that it would be investigating the cause of the incident. It has also offered apology for those affected and promised support to affected and their families.

Meanwhile, the state Industries Minister, Goutam Reddy, stated that it appeared as if the plant did not follow proper procedures and guidelines during its reopening, and that legal action would be taken against the company. Investigators have also found that safety precautions had not been followed, calling it a “crime of omission“.

An official statement from LG Polymers itself suggests that management were aware of a possible disaster. Industries Minister Reddy has placed the burden of proof on LG Polymers to prove that there was no negligence on its part. A negligence and culpable homicide complaint has been lodged against the management of the plant.

LG Polymers have also admitted that it had expanded operations without due consent from regulatory authorities. On top of that, no preparatory mechanisms (a mandatory rule in India) were in place to handle an emergency state.

Contrary to this, other governmental and investigation authorities have issued statements that might suggest an act of compliance between the company and the authorities. The Director General of Police (Andhra Pradesh) claimed that all the protocols were being followed. Similarly, Chief Minister of the state stated that the company involved was a “reputed” one.

India: A history of toxic ‘accidents’.

When accidents become a regular phenomenon, is it even fair to call those ‘accidents’? Workplace accidents that kill humans and nonhumans, and pollutes natural entities (making the impacts last years, or decades, after the original accident) are not new to the country. Some of the most notable accidents being the Union Carbide gas tragedy (1984), Bombay docks explosion (1944), Chasnala mining disaster (1975), Korba Chimney collapse (2009), NTPC power plant explosion (2017), and Jaipur oil depot fire (2009).

The gas leak in Andhra Pradesh was one of three similar accidents within the same day in India. A paper mill in Shakti Paper Mill, Chhattisgarh (a state bordering Andhra Pradesh) hours before Vishakhapatnam accident, due to which seven workers were hospitalized. Similarly, later the same day, a boiler exploded at Neyveli Lignite Corporation in Tamilnadu (southernmost state of India), killing 1 and injuring 5.

These leaks comes just weeks after the coal plant accident in Singrauli. The coal plant leak itself was third of its kind in the past 12 months in the same area.

The new gas leak has also reminded some of the tragic Bhopal gas leak in 1984. More than 40 tonnes of deadly chemicals used in the manufacture of pesticides were released, resulting in an estimated fatalities between 16,000 and 30,000. After 35 years, the effects of the gas leak is still being felt among new born babies. The maximum charges faced by the perpetrators of the “world’s worst industrial disaster” was a two-years’ sentence in prison, and a fine of ₹5,00,000, sentenced 25 years after the incident.

Where do we place the accountability?

Perhaps the gas leak was a result of the Indian government’s premature decision to reopen the economy despite increasing cases of Covid-19 infections.

Perhaps the regulatory agencies are also at fault for failing to ensure that proper procedures were followed by the management while reopening the plant. In a place where enforcement of regulations have always been lax, the temporary closure of plants during the lockdown only exacerbated the problem.

Or perhaps, the plant’s management are a fault for not following the procedures and protocols, especially given that they were aware of the potential hazards and still failed to act on them.

Where we place the accountability for this gas leak often follows directly from who we believe is responsible for the leak in the first place. Given the frequency of industrial ‘accidents’ in India, would it be fair to place the accountability of this particular leak based on closely weighing which actor is most at fault for this isolated event? Or should this event be viewed as only the latest in a long series of industrial “accidents” occurring in India?

Certainly the government and the management could be held accountable for their negligence.

But where do we place the responsibility of opening a potentially toxic-gas-leaking plant in a residential area in the first place? Toxic chemicals like Styrene have always been a risk to the health and lives of humans and nonhumans. This, however, does not stop new plants (with inherent risks of fatal accidents) from being built in close proximities to natural communities.

The corporations and the elite classes that reap the benefits from these plants, after all, do not have to live anywhere near to these plants. The ones who are the most vulnerable to the risks of such accidents (both human and nonhumans) do not have a say in any operation of the plant. This is a classic example of ‘privatization of profits, externalization of costs and risks‘ notion upon which the current globalized, imperialist, capitalist system is based.

Corporations, by their very definitions, are created to maximize profits for their shareholders, disregarding any concerns for morality or compassion. When a corporation’s actions harm others, but maximizes its own profits, should it be blamed for acting in a way consistent with its design, or should we blame the culture that came up with this design in the first place?

In this case, the corporation failed to abide by the regulations and protocols in its jurisprudence. Even this is not a novel behavior for a corporation. In some cases, corporations have challenged, or even modified, laws of a nation.

As much as the corporation could be said to be acting in a way consistent to the rules of its creation, the same could not be said for the government. Ideally, a government should give precedence to the greater good of the (human) society over the selfishness of an individual (or in this case, a legal entity). The government failed to do so in two ways: by allowing the plant to open in the first place, and by reopening the plant without consideration of the risks involved. In both instances, economic gains were prioritized over the wellbeing of the human and natural communities.

Eventually, the burden of responsibility has fallen on the ones most vulnerable to these risks. Initially, the local people have organized protests to permanently shut the plant, after which LG Polymers began transporting 13,000 tonnes of Styrene gas back to its parent company in South Korea. Statements from authorities indicate a “revamping” of the plant. Closure of the plant seems to not have been discussed.

More recently, the demands have been modified to take a more moderate stance: including free ration for the villagers for 2 months, and that the workers previously employed on a contract basis be provided with a permanent job.

Salonika is an organizer at DGR South Asia and is based in Nepal. She believes that the needs of the natural world should trump the needs of the industrial civilization.

Featured image: Vishakhapatnam skyline by Av9, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

by DGR News Service | May 25, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

An upcoming episode of The Green Flame podcast will focus on answering listener questions. Do you have questions for us? Want us to break down an issue that is bothering you, or that you want clarification on? What are you wondering about Deep Green Resistance, our analysis, our work, or how to get involved? This is a good chance to get answers.

Here’s how to submit your questions:

About The Green Flame

The Green Flame is a Deep Green Resistance podcast offering revolutionary analysis, skill sharing, and inspiration for the movement to save the planet by any means necessary. Our hosts are Max Wilbert and Jennifer Murnan.

Subscribe to The Green Flame Podcast

by DGR News Service | May 23, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This excerpt is from Derrick Jensen’s unpublished book “The Politics of Violation.” It has been edited slightly for publication here. The book is in need of a publisher. Please contact us if you wish to speak with Derrick about this.

By Derrick Jensen

For more than two thousand years, a war has been waged over the soul and direction of anarchism.

On one hand, there are those who understand the straightforward and obvious premises that at least to me form the foundation of anarchism: that governments exist in great measure to serve the interests of the governors and others of their class; and that we in our communities are capable of governing ourselves.

And on the other hand, there are those who argue that all constraints on their own behavior are oppressive, and so for whom the point of anarchism is to remove all of these constraints.

I researched and wrote this book in an attempt to understand this war, in the hope that understanding this war can help us understand how and why anarchism has become a haven for so much behavior that is community- and movement-destroying; how and why a movement claiming to show that humans are capable of self-governance so often seems to do everything it can to show the opposite; how and why a movement that claims to be about ending all forms of oppression can be so full of bullying, abuse, and misogyny.

If we all understand this, might we as a society move both anarchism and the larger culture away from these behaviors and toward more sane and sustainable communities?

It became clear to me, however, that the book is about more than anarchism. In part it’s about differences between understanding and learning from a political philosophy—any political philosophy—and turning that philosophy into an identity; what happens when the former ossifies into the latter. This is a problem not just in anarchism but in more or less all philosophies.

When Harm is Left Unchecked

A strength of anarchism is that many anarchists are willing to struggle for their beliefs, and to fight power head on. A weakness is that too many anarchists are too often not strategic, tactical, or moral in choosing their fights, including how they will fight, and in choosing the targets of their attacks.

Severino di Giovanni provides a great example from the 1930s. He was an anarchist in Argentina who started a bombing campaign targeting fascists and also, because of the killings of Sacco and Vanzetti, bombing targets associated with the United States. We can argue over whether his actions were appropriate. And the anarchists in Argentina certainly did argue over it, which leads to why I bring him up: one of the anarchists who spoke against his bombing campaign (saying it would lead to a right wing coup, which in fact happened soon after) was murdered.

Guess who was the prime suspect in his murder?

…

I could provide hundreds of examples of atrocious behavior that have become normalized among too many anarchists. For that matter I could provide hundreds of examples that have happened to me, from threats of death and other physical violence to the posting to the internet of pictures of me Photoshopped to simulate bestiality. Probably the most telling action has been that anarchists arranged for my elderly, disabled, functionally-blind mother to receive harassing phone calls every fifteen minutes from 6:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. for weeks on end.

The point isn’t that they did this to me (and my mother): I’ve known too many people who’ve received their own version of this treatment.

Part of the point is that some people are terrible human beings. Change a few details, and anyone could tell similar stories from most other movements or organizations. And so this book becomes a case study of some of the harm terrible human beings can, if left unchecked, do to movements.

So, generically: What sorts of terrible people does your movement/organization support? And what harms do these people cause? Ecofeminist Charlene Spretnak has written extensively on social change movements, and has talked about how abusive behavior drives away people, especially women, in “huge numbers. That’s a brain- and talent-drain these movements cannot afford.”

What can we do about that?

An Insult to One is Injury To All

Here’s another example of the sort of community-destroying behavior that has come to characterize too much anarchism. A few years ago, I was discovered by the Glenn Beck arm of the right wing. Within two weeks I’d received literally hundreds of death threats from them, many of which were highly detailed in what was to be done to me (e.g., photos of castration) and in information about where I live, my schedule, and so on. In response to these threats I bought a gun and installed bars over my doors and windows. I also called the police and the FBI. I didn’t believe the police and FBI would be particularly helpful (they weren’t), but I wanted for there to be an official record of the threats for two reasons. The first is that on the remote chance someone did kill or injure me, people would at least have an idea where to start looking for the perpetrators. The second is that if someone attempted to harm me and I had to use lethal force to protect myself, it would already be a matter of public record that I had reason to fear for my life. I could imagine a court scene playing out after I was charged with murder for killing someone who had attempted to kill me.[1]

The prosecuting attorney asks, “Were you afraid for your life?”

“Yes.”

“Did you call the police?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

A long silence while I consider that it wouldn’t be particularly useful to say I didn’t call the police because to do so is evidently against anarchist ideology.

The prosecuting attorney continues, “Then I guess you weren’t very afraid, were you?”

Trial over. I lose.

The point is that when I told my neighbors I’d received death threats, they responded as you’d expect decent human beings to respond—with sympathy and expressions of concern for my safety. Some took tangible steps to help guarantee this safety. For crying out loud, a member of the local Tea Party helped me install the bars. This is what members of a community do. An insult to one is an injury to all, remember?

On the other hand, with few exceptions I received little positive support from anarchists, who instead accused me of making up the threats, called me a coward for paying attention to them (many of these particular comments were, ironically enough, anonymous), threatened to kill me themselves, or excoriated me for calling the police.[2] Anarchists quickly labeled me a “cop lover,” then “pig fucker,” then “snitch,” then “someone who rats out comrades.” Soon, anarchists were accusing me of “regularly working with the FBI and the police,” and of being a “paid police informer.” It wasn’t long before some were saying, “Word on the street is that he’s been a fed from the beginning. They wrote all his books.”

To Distort is To Control

How does a political philosophy that leads people to act as did those young men I described who became bodyguards for the victim of a sexual assault lead others to act so despicably? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used, as it has been, as an excuse for men to sexually or otherwise physically assault women? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used to support, as we’ll see, the sexual abuse of children? And how can we prevent all of this from happening in the future?

Can anarchism be fixed?

We should ask these questions of every social movement. This questioning is especially important for those who are inside these movements.

Change a few words, and this book could have been written about almost any social movement or group. I know female Christians (now former Christians) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male Christians, and then pressured by the Christian community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female soldiers (now ex-military) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male soldiers, and then pressured by the military community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female athletes (now former athletes) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male athletes, and then pressured by the local athletic community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female police officers (now former ones) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male police officers, and then pressured by the local police community not to go to the police (!!) because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

Substitute the words musicians, teachers, loggers, environmental activists, actors, writers, and the story is the same.

So this book provides an exploration of what rape culture does to movements, and how movements are deformed or destroyed by the imperative to violate that is central to patriarchy, central to the dominant culture.

I’ve long been a critic of Christianity, but I can’t tell you how many times, especially when I used to drive beaters (I bought four cars in a row for one dollar each, and considered these good deals since the cars must have been worth at least twice that much), that I’ve been stuck by a road, and the person who stops to help fix my car has been a Christian stranger, motivated by a calling to do good in the name of their belief system. Yet, Christianity has been and still is used to justify—and leads to—atrocious behavior such as gynocide, genocide, ecocide. When I think of Christians, I think of a wonderfully kind man and woman who invited me into their home when I was living in my truck in my twenties. And when I think of Christians I think of misogynistic, racist, pro-imperialist buffoons. I think of Christians rationalizing slavery, rationalizing capitalism. I think of Christians burning women they considered witches, burning Native Americans, burning the world. I think of Christians burning other Christians. How does a religion that leads to wonderful people like the couple who gave me a place to stay also lead to such routinely atrocious behavior?

Likewise, when I think of the American Indian Movement, I think of brave women and men standing up to the United States government and to corrupt tribal governments. And I think of misogynist murdering assholes raping and killing Anna Mae Aquash, among others.

When I think of the Black Panthers I think of free breakfast programs for children and black pride and protecting neighborhoods from police violence. And I think of systematic programs of rape by male Panthers against women both black and white.

I’m sure you can find your own examples.

What is wrong with these movements?

Justifying Oppression

Obviously, anarchism is not the only philosophy that has been used to rationalize or facilitate the sexual exploitation of women. We’d be hard-pressed to find philosophies within patriarchy that haven’t. And certainly, groups other than anarchists have facilitated this exploitation. Organizations from the police to the courts to the military to churches to universities to professional sports organizations to the NCAA to the music industry to the Boy Scouts to pretty much you-name-it have facilitated or covered up sexual assaults by men on women or children.

Those of us who care about stopping atrocities need to ask: How does any particular philosophy justify or otherwise facilitate atrocious behavior? And what are we going to do to stop these atrocities?

Panem et Circenses

I became interested in anarchism when I first became politicized—that is, when I began to understand that, as economists are so fond of saying and even more fond of then ignoring, there is no free lunch. In other words, all rhetoric and rationalization aside, the wealth of some comes at the expense of others.

In other words, empires require colonies.

It immediately became clear to me that while much of how a state disperses resources (e.g., time and money) could be perceived as citizen maintenance,[3]—or, with thanks to Juvenal, providing enough “bread and circuses” to keep the exploited from tearing out the throats of the rich—the state’s most important function by far, and the primary reason for its existence, is to take care of business; that is, to take care of the interests of those in power.

Burden of Proof

So there’s a sense in which the bad behavior of too many anarchists is not only appalling but tragic, Bad behavior among anarchists represents thousands of years of lost opportunity for meaningful social change, because while some anarchist analysis makes sense, the behavior of too many of those who call themselves anarchists can get in the way of people wanting to share a movement with them.

The sensible analysis begins with this: The state isn’t necessary for human survival, and in fact the state primarily serves the interests of the governors and others of their class.

If you don’t believe governments primarily serve the interests of the governing class, ask yourself if you believe governments take better care of human beings, or of corporations. If governments had as their primary function the protection of human and nonhuman communities, would they devise a tool—the corporation—that exists explicitly to privatize profits and externalize costs, that is, to funnel wealth to the already wealthy at the expense of others? I’ve asked tens of thousands of people all over the United States and Canada if they believe governments better serve humans or corporations, and no one ever says humans.

Let’s throw in a couple more common-sense comments about anarchism. The first is by the American linguist, philosopher, scientist and activist Noam Chomsky (who, by the way, is also hated by many of the anarchists on the wrong side of the war for the soul of anarchism, who call him “a pussy” and “the old turd”): “That is what I have always understood to be the essence of anarchism: the conviction that the burden of proof has to be placed on authority, and that it should be dismantled if that burden cannot be met. Sometimes the burden can be met. If I’m taking a walk with my grandchildren and they dart out into a busy street, I will use not only authority but also physical coercion to stop them. The act should be challenged, but I think it can readily meet the challenge. And there are other cases; life is a complex affair, we understand very little about humans and society, and grand pronouncements are generally more a source of harm than of benefit. But the perspective is a valid one, I think, and can lead us quite a long way.”[4]

Makes sense, right?

Now let’s throw in another, by Edward Abbey: “Anarchism is not a romantic fable but the hardheaded realization, based on five thousand years of experience, that we cannot entrust the management of our lives to kings, priests, politicians, generals, and county commissioners.”[5]

This all seems pretty obvious, and leads to the question, why aren’t more people anarchists?

[1] And most of us have read accounts of this sort of thing, for example, so many of the women in prison for killing their abusive husbands. In the town where I live a woman is right now being charged with murder for shooting her husband in front of witnesses who all swear that he routinely beat her, that this night he was punching and kicking her, and just before she shot him he yanked her by her hair out of a car as she was attempting to escape. Even the dead man’s mother is begging prosecutors to drop the charges.

[2] This whole question of never speaking to the police cuts to the heart of one of the problems with too much anarchism. Just as with any rigidified ideology, the ideology itself comes to supplant circumstance and common sense. For example, when attorneys advise you never to talk to the police, they mean when you’re under suspicion, not under every circumstance. If anarchists saw Ted Bundy knock out a woman, load her into his car, then drive off, they wouldn’t call the cops? What are they going to do, hop on their bikes and pedal after him?

[3] Such as providing water and waste disposal for the people. But the fact is agriculture and industry account for more than 90 percent of human water usage and 97 percent of waste production. Governments “take care of” big business under the guise of “citizen maintenance.”

[4] Doyle, Kevin, “Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism, and Hope for the Future,” Red and Black Review, 1995, http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/rbr/noamrbr2.html – Site visited 6/20/2016.

[5] Abbey, Edward, A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1990.

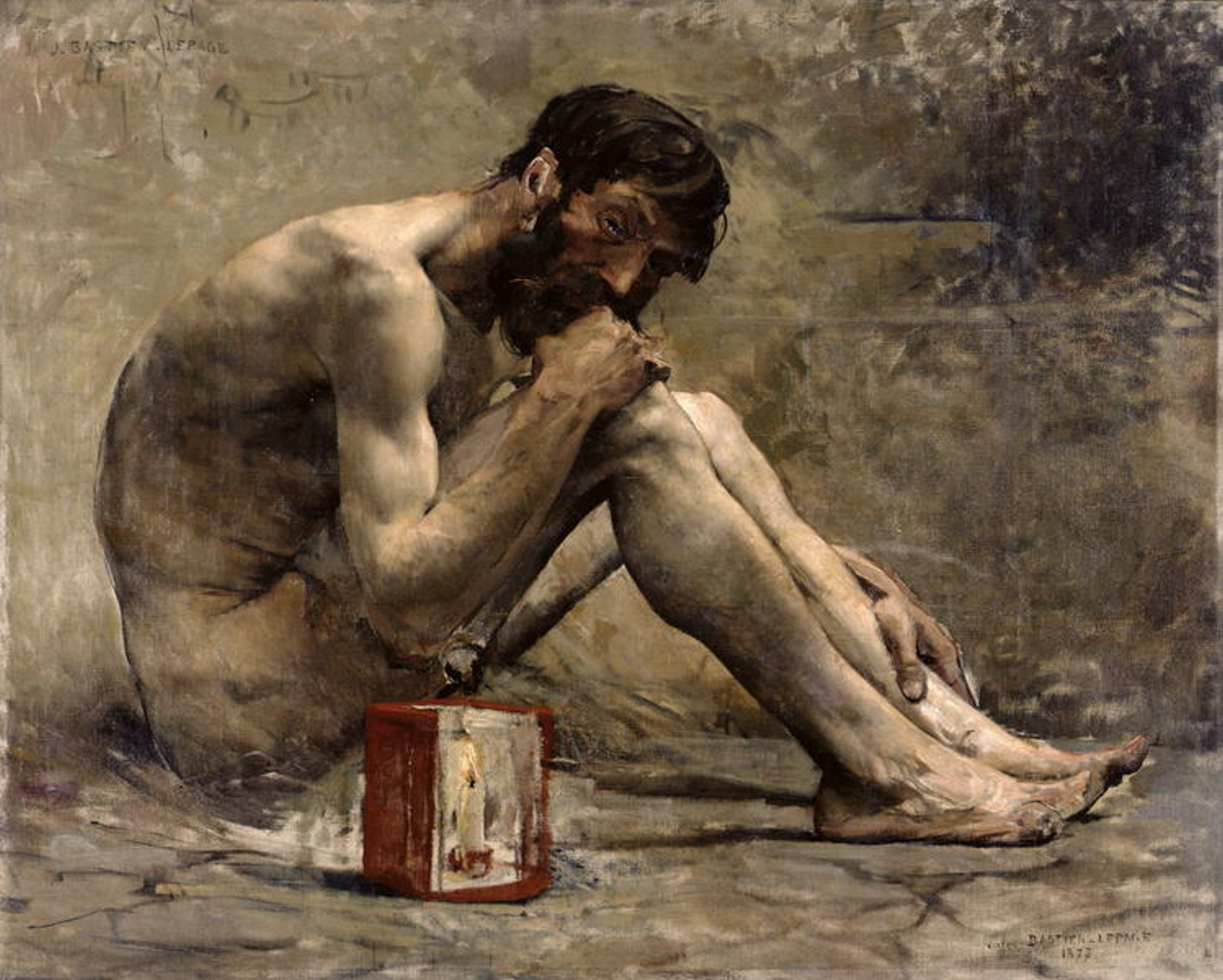

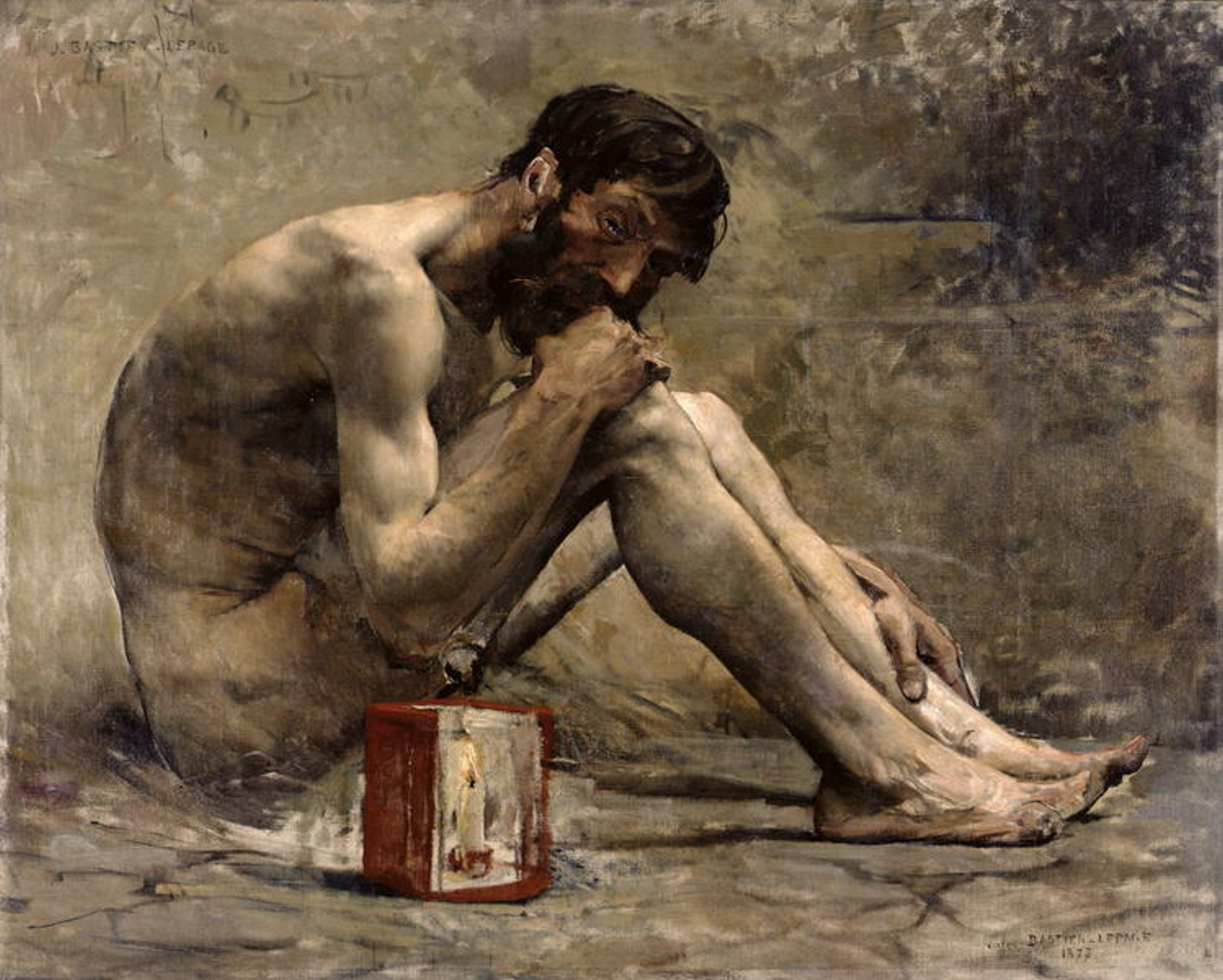

Featured image: 1873 painting of Diogenes, an ancient Greek Cynic and prominent figure in proto-anarchism. By Jules Bastien-Lepage.

About the Author

Derrick Jensen is a co-author of Deep Green Resistance, and the author of Endgame, The Culture of Make Believe, A Language Older than Words, and many other books. He was named one of Utne Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World” and won the Eric Hoffer Award in 2008. He has written for Orion, Audubon, and The Sun Magazine, among many others.