by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 15, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

I do not wish to kill nor to be killed, but I can foresee circumstances in which both these things would be by me unavoidable. We preserve the so-called peace of our community by deeds of petty violence every day. Look at the policeman’s billy and handcuffs! Look at the jail! Look at the gallows! Look at the chaplain of the regiment! We are hoping only to live safely on the outskirts of this provisional army. So we defend ourselves and our hen-roosts, and maintain slavery.

—Henry David Thoreau, “A Plea for Captain John Brown”

Anarchist Michael Albert, in his memoir Remembering Tomorrow: From SDS to Life after Capitalism, writes, “In seeking social change, one of the biggest problems I have encountered is that activists have been insufficiently strategic.” While it’s true, he notes, that various progressive movements “did just sometimes enact bad strategy,” in his experience they “often had no strategy at all.”1

It would be an understatement to say that this inheritance is a huge problem for resistance groups. There are plenty of possible ways to explain it. Because we sometimes don’t articulate a clear strategy because we’re outnumbered and overrun with crises or immediate emergencies, so that we can never focus on long-term planning. Or because our groups are fractured, and devising a strategy requires a level of practical agreement that we can’t muster. Or it can be because we’re not fighting to win. Or because many of us don’t understand the difference between a strategy and a goal or a wish. Or because we don’t teach ourselves and others to think in strategic terms. Or because people are acting like dissidents instead of resisters. Or because our so-called strategy often boils down to asking someone else to do something for us. Or because we’re just not trying hard enough.

One major reason that resistance strategy is underdeveloped is because thinkers and planners who do articulate strategies are often attacked for doing so. People can always find something to disagree with. That’s especially true when any one strategy is expected to solve all problems or address all causes claimed by progressives. If a movement depends more on ideological purity than it does on accomplishments, it’s easy for internal sectarian arguments to take priority over getting things done. It’s easier to attack resistance strategists in a burst of horizontal hostility than it is to get things together and attack those in power.

The good news is that we can learn from a few resistance groups with successful and well-articulated strategies. The study of strategy itself has been extensive for centuries. The fundamentals of strategy are foundational for military officers, as they must be for resistance cadres and leaders.

PRINCIPLES OF WAR AND STRATEGY

The US Army’s field manual entitled Operations introduces nine “Principles of War.” The authors emphasize that these are “not a checklist” and do not apply the same way in every situation. Instead, they are characteristic of successful operations and, when used in the study of historical conflicts, are “powerful tools for analysis.” The nine “core concepts” are:

Objective. “Direct every military operation toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective.” A clear goal is a prerequisite to selecting a strategy. It is also something that many resistance groups lack. The second and third requirements—that the objective be both decisive and attainable—are worth underlining. A decisive objective is one that will have a clear impact on the larger strategy and struggle. There is no point in going after one of questionable or little value. And, obviously, the objective itself must be attainable, because otherwise efforts toward that operation objective are a waste of time, energy, and risk.

Offensive. “Seize, retain, and exploit the initiative.” To seize the initiative is to determine the course of battle, the place, and the nature of conflict. To give up or lose the initiative is to allow the enemy to determine those things. Too often resistance groups, especially those based on lobbying or demands, give up the initiative to those in power. Seizing the initiative positions the fight on our terms, forcing them to react to us. Operations that seize the initiative are typically offensive in nature.

Mass. “Concentrate the effects of combat power at the decisive place and time.” Where the field manual says “combat power,” we can say “force” more generally. When Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest summed up his military theory as “get there first with the most,” this is what he was talking about. We must engage those in power where we are strong and they are weak. We must strike when we have overwhelming force, and maneuver instead of engaging when we are outmatched. We have limited numbers and limited force, so we have to use that when and where it will be most effective.

Economy of Force. “Allocate minimum essential combat power to secondary efforts.” In order to achieve superiority of force in decisive operations, it’s usually necessary to divert people and resources from less urgent or decisive operations. Economy of force requires that all personnel are performing important tasks, regardless of whether they are engaged in decisive operations or not.

Maneuver. “Place the enemy in a disadvantageous position through the flexible application of combat power.” This hinges on mobility and flexibility, which are essential for asymmetric conflict. The fewer a group’s numbers, the more mobile and agile it must be. This may mean concentrating forces, it may mean dispersing them, it may mean moving them, or it may mean hiding them. This is necessary to keep the enemy off balance and make that group’s actions unpredictable.

Unity of Command. “For every objective, ensure unity of effort under one responsible commander.” This is where some streams of anarchist culture come up against millennia of strategic advice. We’ve already discussed this under decision making and elsewhere, but it’s worth repeating. No strategy can be implemented by consensus under dangerous or emergency circumstances. Participatory decision making is not compatible with high-risk or urgent operations. That’s why the anarchist columns in the Spanish Civil War had officers even though they despised rulers. A group may arrive at a strategy by any decision-making method it desires, but when it comes to implementation, a hierarchy is required to undertake more serious action.

Security. “Never permit the enemy to acquire an unexpected advantage.” When fighting in a panopticon, this principle becomes even more important. Security is a cornerstone of strategy as well as of organization.

Surprise. “Strike the enemy at a time or place or in a manner for which they are unprepared.” This is key to asymmetric conflict—and again, not especially compatible with a open or participatory decision-making structures. Resistance movements are almost always outnumbered, which means they have to use surprise and swiftness to strike and accomplish their objective before those in power can marshal an overpowering response.

Simplicity. “Prepare clear, uncomplicated plans and clear, concise orders to ensure thorough understanding.” The plan must be clear and direct so that everyone understands it. The simpler a plan is, the more reliably it can be implemented by multiple cooperating groups.

In fact, these strategic principles might as well come from a different dimension as far as most (liberal) protest actions are concerned. That’s because the military strategist has the same broad objective as the radical strategist: to use the decisive application of force to accomplish a task. Neither strategist is under the illusion that the opponent is going to correct a “mistake” if this enemy gets enough information or that success can occur by simple persuasion without the backing of political force. Furthermore, both are able to clearly identify their enemy. If you identify with those in power, you’ll never be able to fight back. An oppositional culture has an identity that is distinct from that of those in power; this is a defining element of cultures of resistance. Without a clear knowledge of who your adversary is, you either end up fighting everyone (in classic horizontal hostility) or no one, and, in either case, your struggle cannot succeed.

In the US Army’s field manual on guerrilla warfare, entitled Special Forces Operations, the authors go further than the general principles of war to kindly describe the specific properties of successful asymmetric conflict. “Combat operations of guerilla forces”—and, I would add, resistance and asymmetric forces in general—“take on certain characteristics that must be understood.”2 Six key characteristics must be in place for resistance operations:

Planning. “Careful and detailed.… [p]lans provide for the attack of selected targets and subsequent operations designed to exploit the advantage gained.… Additionally, alternate targets are designated to allow subordinate units a degree of flexibility in taking advantage of sudden changes in the tactical situation.” In other words, it is important to employ maneuvering and flexible application of combat power. It’s important to emphasize that planning is notabout coming up with a concrete or complex scheme. The point is to plan well enough that they have the flexibility to improvise. It might sound counterintuitive, but the goal is to create an adaptable plan that offers many possibilities for effective action that can be applied on the fly.

Intelligence. “The basis of planning is accurate and up-to-date intelligence. Prior to initiating combat operations, a detailed intelligence collection effort is made in the projected objective area. This effort supplements the regular flow of intelligence.” That’s strategic and operational intelligence. On a tactical level, “provisions are made for keeping the target or objective area under surveillance up to the time of attack.”

Decentralized Execution. “Guerrilla combat operations feature centralized planning and decentralized execution.” It is necessary to have a coherent plan, and in order for that plan to be a surprise, the details often have to be kept secret. A centralized plan allows separate cells to carry out their work independently but still accomplish something through coordination and building toward long-term objectives. Decentralized execution is needed to reach multiple targets for a group that lacks a command and control hierarchy.

Surprise. “Attacks are executed at unexpected times and places. Set patterns of action are avoided. Maximum advantage is gained by attacking enemy weaknesses.” When planning a militant action, resisters don’t announce when or where. The point is not to make a statement, but to make a decisive material impact on systems of power. This can again be enhanced by coordination between multiple cells. “Surprise may also be enhanced by the conduct of concurrent diversionary activities.”

Short Duration Action. “Usually, combat operations of guerrilla forces are marked by action of short duration against the target followed by a rapid withdrawal of the attacking force. Prolonged combat action from fixed positions is avoided.” Resistance groups don’t have the numbers or logistics for sustained or pitched battles. If they try to draw out an engagement in one place, those in power can mobilize overwhelming force against them. So underground resistance groups appear, accomplish their objectives swiftly, and then disappear again.

Multiple Attacks. “Another characteristic of guerrilla combat operations is the employment of multiple attacks over a wide area by small units tailored to the individual missions.” Again, coordination is required. “Such action tends to deceive the enemy as to the actual location of guerrilla bases, causes him to over-estimate guerrilla strength and forces him to disperse his rear area security and counter guerrilla efforts.” That is, when those in power don’t know where an attack will come, they must spend effort to defend every single potential target—whether that means guarding them, increasing insurance costs, or closing down vulnerable installations. And as forces become more dispersed in order to guard sprawling and vulnerable infrastructure, they become less concentrated and correspondingly make easier targets.

Other writers on resistance struggles have shared these understandings. Che Guevara outlined similar strategy and tactics in his book Guerilla Warfare (1961), which itself followed from Mao Tse-Tung’s 1937 book on the subject. Colin Gubbins, former head of the British Special Operations Executive, wrote two pamphlets on the subject for use in Occupied Europe (written not long after Mao’s book). These pamphlets—The Partisan Leader’s Handbook and The Art of Guerilla Warfare—were based in part on what the British learned from T. E. Lawrence, but also from their attempts to quash resistance warfare in Ireland, Palestine, and elsewhere. In The Partisan Leader’s Handbook, Gubbins touched on the elements of surprise (“the most important thing in everything you undertake”), mobility, secrecy, and careful planning. “The whole object of this type of warfare is to strike the enemy, and disappear completely leaving no trace; and then to strike somewhere else and vanish again. By these means the enemy will never know where the next blow is coming,” he wrote.

Gubbins also urged resisters to “never engage in any operation unless you think success is certain.” Small resistance units don’t have the numbers or morale to absorb unnecessary losses. Resistance groups should only engage the enemy at points and times where they can overwhelm. The first step to take before any action is to plan a safe line of retreat, and “break off the action as soon as it becomes too risky to continue.” A newly founded resistance group often lacks the experience and training to accurately gauge how risky a situation is, which is why Gubbins recommends erring on the side of caution. It is better to learn iteratively and build up from a number of small successes than to get caught attempting operations that are too large and apt to end in failure. The takeaway message: successful resistance movements choose their battles carefully.

Just as asymmetric strategies require specific characteristics for success, they also have definite limitations.3 Resistance forces typically have “limited capabilities for static defensive or holding operations.” They often want to hold territory, to stand and fight. But when they try, it usually gets them killed, unless they’ve spent years developing extensive social and military groundwork and have a large force and popular support. Another limitation is that, especially in the beginning, resistance forces lack “formal training, equipment, weapons, and supplies” that would allow them to undertake large-scale operations. This can be gradually remedied through ongoing recruitment and training, good logistics, and the security and caution required to limit losses through attrition; however, resistance forces are often dependent on local supporters and auxiliaries—and perhaps an outside sponsoring power—for their supplies and equipment. If they can’t find those supporters, they will probably lose.

Communications offer another set of limitations. Communications in underground groups are often difficult, limited, and slow. This also applies to organizational command; the more decentralized an organization is, the longer it takes to propagate decisions, orders, and other information. And because resistance groups have small numbers and finite resources, “the entire project is dependent upon precise, timely, and accurate intelligence.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 10, 2018 | Prostitution

by Joanna Pinkiewicz / Deep Green Resistance Australia

Australia has different legislations in regards to prostitution in each state. For example New South Wales has almost full decriminalisation and definitely in favour of brothel owners, less so for individual, who can be charged for “living on the earnings of prostitute” or soliciting for prostitution outside dwelling, school, church or hospital. In Victoria street sex work is illegal and brothels and premises based work needs to be licenced. In reality, NSW police reports show that legal operations have connections to organised crime, drug and people trafficking and in Victoria we are seeing surge in premises, both registered and under the cover of massage parlours and unchecked conditions and practices within registered brothels.

While many countries in Europe and recently in the US (US Greens Party voted for change in policy on prostitution and support the Nordic Model) the push to introduce the abolitionist approach has been coming from the left in the name of justice and equality for women, in Australia the left has been supporting the “sex worker” lobby groups and the sex industry itself, contributing to normalisation of sex purchase by men and expansion of the sex trade industry.

It came as a bit as a surprise to see that in April a branch of Victorian Liberal Party proposed a motion in support of the Nordic Model, which aims at addressing the demand for prostitution via penalising the buyer and not targeting those who are in prostitution.

It also came as a surprise to have a very public supporter of the Nordic Model within the Greens Party, Kathleen Maltzahn, state that she won’t support the Vic Liberal Party’s motion for the Nordic Model if and when it goes up for a vote. Maltzahn is known for her grass roots work, Project Respect, an exit program for women in prostitution, which she established after working in Philippines and seeing first-hand the insidious nature of sex trade. She has been going against her own party’s policy, which supports full decriminalisation. She has been widely criticised by those in her own party as well as those in the pro sex lobby groups. Upon the release of her statement, a criticism also came from parts of the abolition movement. I does look like a significant pressure has been placed upon her from the party leaders to make that statement. One thing is clear, we need more radical feminist analysis of prostitution in the Green’s party, more radical feminists being active within the mainstream left to bring about change.

Many activists within the abolishion movement hesitate at working with the Liberal Party or Christian organisations, due to disagreements on details or due to their stand regarding other women’s rights issues.

I have asked Simone Watson, director of Nordic Model Australia Coalition, what she thinks about working with the Liberal Party on this and she said this:

“My concerns around the Victorian Liberal Party endorsement of the Nordic/Abolitionist Model were that their first proposal was not in fact the Nordic/Abolitionist model at all.

“The initial draft was a serious red flag to me as it only focused on criminalising buyers in illegal brothels. It is already illegal to buy sexual access in illegal brothels. Yes, it aimed to decriminalise the prostituted women in those same brothels, but offered no exit programs and no changes to legislation across the board. So my reading of it was that it would be doomed to failure. I do not think my concerns around such a premise are unwarranted. It failed to take in to account the inefficacy of prohibition laws on prostitution; it failed to capture the intrinsic and essential point of the abolitionist approach. Their proposal was still rooted in the dangerous ground of prohibition. And prohibition fails. Some saw this as at least a start, however, the Nordic/Abolitionist Model cannot be undertaken half-baked. To do so would be incredibly dangerous and anathema to the law they claimed to be endorsing. To their credit they have since recognised that their initial proposal was incomplete.

“Do I trust them? Well, I have some trust, especially as they took considerable time to listen to survivor’s and our allies’ concerns on this. They certainly have taken more time than the Greens or Labor, which is why the Green Party USA should be commended for their determination to support the abolition of the sex trade and all major parties here should take note of that.

“For me, working with political parties as a sex-trade abolitionist is fraught because I often do not agree with many of their other policies. For example the Liberal’s alliance with anti-woman organisations, those who are against abortion and so on. But if a party is truly dedicated to abolishing the sex-trade, extinguishing the ongoing commodification of women, and women’s rights to be free from sexual exploitation, then I will support them on that particular policy. Again it is hard to trust any particular party on this issue, but if they are willing to amend their initial proposal and actively endorse the Nordic/Abolitionist model as it is intended in full, I support that unequivocally.”

Simone’s response highlights critical issues in approaching the Nordic Model with wrong motivation, poor understanding of the process involved as well as half-baked financial commitment, all critical to its success.

To summarise, the Nordic Model requires a three pronged approach:

- Establishment of exit and support programs for people in prostitution.

- Education of the public and retraining of the police

- Enforcement of the new laws by providing funding to dedicated police people and social workers.

The laws themselves aim at stoping trafficking and curbing growth of the global sex trade via penalising the buyers and pimps.

Other important news from Australia is the upcoming Australian Summit Against Sexual Exploitation (ASASE) on 27-28 of July in Melbourne. Key speakers of the summit on the subject of prostitution are:

- Julie Bindel (UK)

- Sabrinna Valisce (SPACE International)

- Simone Watson (Normac)

- Sarah M Mah (Asian Women for Equality, Canada)

I’m hoping that the summit will bring more allies to the abolition movement in Australia, who can then plan for the consultation process needed when the Nordic Model gets a motion vote in Victoria.

Joanna Pinkiewicz is a DGR Australia member; environmental activist, women’s right activist artist and mother.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 8, 2018 | Direct Action

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “A Taxonomy of Action” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There are four basic ways to directly confront those in power. Three deal with land, property, or infrastructure, and one deals specifically with human beings. They include:

Obstruction and occupation;

Reclamation and expropriation;

Property and material destruction (threats or acts); and

Violence against humans (threats or acts)

In other words, in a physical confrontation, the resistance has three main options for any (nonhuman) target: block it, take it, or break it.

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful … tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful … tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Expropriation has been a common tactic in various stages of revolution. “Loot the looters!” proclaimed the Bolsheviks during Russia’s October Revolution. Early on, the Bolsheviks staged bank robberies to acquire funds for their cause.36 Successful revolutionaries, as well as mainstream leftists, have also engaged in more “legitimate” activities, but these are no less likely to trigger reprisals. When the democratically elected government of Iran nationalized an oil company in 1953, the CIA responded by staging a coup.37 And, of course, guerilla movements commonly “liberate” equipment from occupiers in order to carry out their own activities.

Sabotage is an essential part of war and resistance to occupation. This is widely recognized by armed forces, and the US military has published a number of manuals and pamphlets on sabotage for use by occupied people. The Simple Sabotage Field Manual published by the Office of Strategic Services during World War II offers suggestions on how to deploy and motivate saboteurs, and specific means that can be used. “Simple sabotage is more than malicious mischief,” it warns, “and it should always consist of acts whose results will be detrimental to the materials and manpower of the enemy.”38 It warns that a saboteur should never attack targets beyond his or her capacity, and should try to damage materials in use, or destined for use, by the enemy. “It will be safe for him to assume that almost any product of heavy industry is destined for enemy use, and that the most efficient fuels and lubricants also are destined for enemy use.”39 It encourages the saboteur to target transportation and communications systems and devices in particular, as well as other critical materials for the functioning of those systems and of the broader occupational apparatus. Its particular instructions range from burning enemy infrastructure to blocking toilets and jamming locks, from working slowly or inefficiently in factories to damaging work tools through deliberate negligence, from spreading false rumors or misleading information to the occupiers to engaging in long and inefficient workplace meetings.

Ever since the industrial revolution, targeting infrastructure has been a highly effective means of engaging in conflict. It may be surprising to some that the end of the American Civil War was brought about in large part by attacks on infrastructure. From its onset in 1861, the Civil War was extremely bloody, killing more American combatants than all other wars before or since, combined.40 After several years of this, President Lincoln and his chief generals agreed to move from a “limited war” to a “total war” in an attempt to decisively end the war and bring about victory.41

Historian Bruce Catton described the 1864 shift, when Union general “[William Tecumseh] Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructures.”42Catton writes that “it was also the nineteenth-century equivalent of the modern bombing raid, a blow at the civilian underpinning of the military machine. Bridges, railroads, machine shops, warehouses—anything of this nature that lay in Sherman’s path was burned or dismantled.”43 Telegraph lines were targeted as well, but so was the agricultural base. The Union Army selectively burned barns, mills, and cotton gins, and occasionally burned crops or captured livestock. This was partly an attack on agriculture-based slavery, and partly a way of provisioning the Union Army while undermining the Confederates. These attacks did take place with a specific code of conduct, and General Sherman ordered his men to distinguish “between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.”44

Catton argues that military engagements were “incidental” to the overall goal of striking the infrastructure, a goal which was successfully carried out.45 As historian David J. Eicher wrote, “Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South’s potential and psychology to wage war.”46 The strategy was crucial to the northern victory.

In resistance movements, offensive violence is rare—virtually all violence used by historical resistance groups, from revolting slaves to escaping concentration camp prisoners to women shooting abusive partners, is a response to greater violence from power, and so is both justifiable and defensive. When prisoners in the Sobibór extermination camp quietly killed SS guards in the hours leading up to their planned escape, some might argue that they committed acts of offensive violence. But they were only responding to much more extensive violence already committed by the Nazis, and were acting to avert worse violence in the immediate future.

There have been groups which engaged in systematic offensive violence and attacks directed at people rather than infrastructure. The Red Army Faction (RAF) was a militant leftist group operating in West Germany, mostly in the 1970s and 1980s. They carried out a campaign of bombings and assassination attempts mostly aimed at police, soldiers, and high-ranking government or business officials. Another example would be the Palestinian group Hamas, which has carried out a large number of violent attacks on both civilians and military personnel in Israel. (It is also a political party and holds a legally elected majority in the Palestinian National Authority. It’s often ignored that much of Hamas’s popularity comes from its many social programs, which long predate its election to government. About 90 percent of Hamas’s activities are these social programs, which include medical clinics, soup kitchens, schools and literacy programs, and orphanages.48)

It’s sometimes argued that the use of violence is never justifiable strategically, because the state will always have the larger ability to escalate beyond the resistance in a cycle of violence. In a narrow sense that’s true, but in a wider sense it’s misleading. Successful resistance groups almost never attempt to engage in overt armed conflict with those in power (except in late-stage revolutions, when the state has weakened and revolutionary forces are large and well-equipped). Guerilla groups focus on attacking where they are strongest, and those in power are weakest. The mobile, covert, hit-and-run nature of their strategy means that they can cause extensive disruption while (hopefully) avoiding government reprisals.

Furthermore, the state’s violent response isn’t just due to the use of violence by the resistance, it’s a response to the effectiveness of the resistance. We’ve seen that again and again, even where acts of omission have been the primary tactics. Those in power will use force and violence to put down any major threat to their power, regardless of the particular tactics used. So trying to avoid a violent state response is hardly a universal argument against the use of defensive violence by a resistance group.

The purpose of violent resistance isn’t simply to do violence or exact revenge, as some dogmatic critics of violence seem to believe. The purpose is to reduce the capacity of those in power to do further violence. The US guerilla warfare manual explicitly states that a “guerrilla’s objective is to diminish the enemy’s military potential.”49 (Remember what historian Bruce Catton wrote about the Union Army’s engagements with Confederate soldiers being incidental to their attacks on infrastructure.) To attack those in power without a strategy, simply to inflict indiscriminant damage, would be foolish.

The RAF used offensive violence, but probably not in a way that decreased the capacity of those in power to do violence. Starting in 1971, they shot two police and killed one. They bombed a US barracks, killing one and wounding thirteen. They bombed a police station, wounding five officers. They bombed the car of a judge. They bombed a newspaper headquarters. They bombed an officers’ club, killing three and injuring five. They attacked the West German embassy, killing two and losing two RAF members. They undertook a failed attack against an army base (which held nuclear weapons) and lost several RAF members. They assassinated the federal prosecutor general and the director of a bank in an attempted kidnapping. They hijacked an airliner, and three hijackers were killed. They kidnapped the chairman of a German industry organization (who was also a former SS officer), killing three police and a driver in the attack. When the government refused to give in to their demands to release imprisoned RAF members, they killed the chairman. They shot a policeman in a bar. They attempted to assassinate the head of NATO, blew up a car bomb in an air base parking lot, attempted to assassinate an army commander, attempted to bomb a NATO officer school, and blew up another car bomb in another air base parking lot. They separately assassinated a corporate manager and the head of an East German state trust agency. And as their final militant act, in 1993 they blew up the construction site of a new prison, causing more than one hundred million Deutsche Marks of damage. Throughout this period, they killed a number of secondary targets such as chauffeurs and bodyguards.

Setting aside for the time being the ethical questions of using offensive violence, and the strategic implications of giving up the moral high ground, how many of these acts seem like effective ways to reduce the state’s capacity for violence? In an industrial civilization, most of those in government and business are essentially interchangeable functionaries, people who perform a certain task, who can easily be replaced by another. Sure, there are unique individuals who are especially important driving forces—people like Hitler—but even if you believe Carlyle’s Great Man theory, you have to admit that most individual police, business managers, and so on will be quickly and easily replaced in their respective organizations.50 How many police and corporate functionaries are there in one country? Conversely, how many primary oil pipelines and electrical transmission lines are there? Which are most heavily guarded and surveilled, bank directors or remote electrical lines? Which will be replaced sooner, bureaucratic functionaries or bus-sized electrical components? And which attack has the greatest “return on investment?” In other words, which offers the most leverage for impact in exchange for the risk undertaken?

As we’ve said many times, the incredible level of day-to-day violence inflicted by this culture on human beings and on the natural world means that to refrain from fighting back will not prevent violence. It simply means that those in power will direct their violence at different people and over a much longer period of time. The question, as ever, is which particular strategy—violent or not—will actually work.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 1, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “A Taxonomy of Action” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

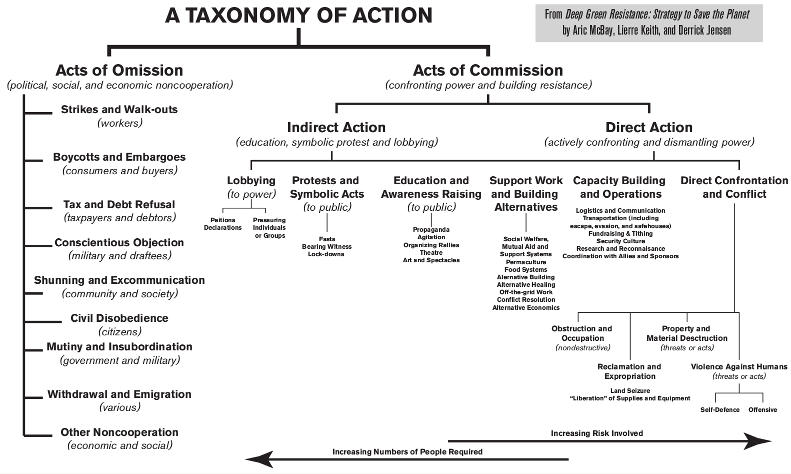

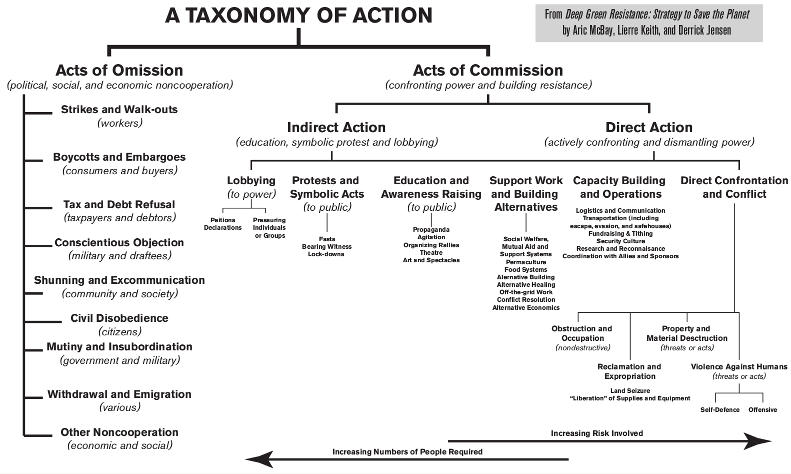

As we’ve made clear, acts of omission are not going to bring down civilization. Let’s talk about action with more potential. We can split all acts of commission into six branches:

- lobbying;

- protests and symbolic acts;

- education and awareness raising;

- support work and building alternatives;

- capacity building and logistics;

- and direct confrontation and conflict.

The illustration “Taxonomy of Action” groups them by directness. The most indirect tactics are on the left, and become progressively more direct when moving from left to right. More direct tactics involve more personal risk. (The main collective risk is failing to save the planet.) Direct acts require fewer people.

Figure 6-1. Click for larger image.

Lobbying seems attractive because if you have enough resources (i.e., money), you can get government to do things for you, magnifying your actions. Success is possible when many people push for minor change, and unlikely when few people push for major change. But lobbying is too indirect—it requires us to try to convince someone to convince other people to make a decision or pass a law, which will then hopefully be enacted by other people, and enforced by yet a further group.

Lobbying via persuasion is a dead end, not just in terms of taking down civilization, but in virtually every radical endeavor. It assumes that those in power are essentially moral and can be convinced to change their behavior. But let’s be blunt: if they wanted to do the right thing, we wouldn’t be where we are now. Or to put it another way, their moral sense (if present) is so profoundly distorted they are almost all unreachable by persuasion.

And what if they could be persuaded? Capitalists employ vast armies of professional lobbyists to manipulate government. Our ability to lobby those in power (which includes heads of governments and corporations) is vastly outmatched by their ability to lobby each other. Convincing those in power to change would require huge numbers of people. If we had those people, those in power wouldn’t be convinced—they would be replaced. Convincing them to mend their ways would be irrelevant, because we could undertake much more effective action.

Lobbying is simply not a priority in taking down civilization. This is not to diminish or insult lobbying victories like the Clean Water Act and the Wildlife Act, which have bought us valuable time. It is merely to point out that lobbying will not work to topple a system as vast as civilization.

When effective, demonstrations are part of a broader movement and go beyond the symbolic. There have been effective protests, such as the civil rights actions in Birmingham, but they were not symbolic; they were physical obstructions of business and politics. This disruption is usually illegal. Still, symbolic protests can get attention. Protests are most effective at “getting a message out” when they focus on one issue. Modern media coverage is so superficial and sensational that nuances get lost. But a critique of civilization can’t be expressed in sound bytes, so protests can’t publicize it. And civilization is so large and so ubiquitous that there is no one place to protest it. Some resistance movements have employed protests, to show strength and attract recruits, but the majority of people will never be on our side; our strategy needs to be based on effectiveness, not just numbers.

For public education to work, several conditions must be met. The resistance education and propaganda must be able to outcompete the mass media. The general public must be able and willing to unravel the prevailing falsehoods, even if doing that contravenes their own social, psychological, and economic self-interest. They must have accessible ways to change their actions, and they must choose morally preferable actions over convenient ones. Unfortunately, none of these conditions are in place right now.

Another drawback of education is its built-in delay; it may take years before a given person translates new information into action. But as we know, the planet is being murdered, and the window for effective action is small. For deep green resisters, skills training and agitation may be more effective than public education.

Education won’t directly take down civilization, but it may help to radicalize and recruit people by providing a critical interpretation of their experiences. And as civilization continues to collapse, education may encourage people to question the underlying reasons for a declining economy, food crises, and so on.

These support structures directly enable resistance. The Quakers’ Society of Friends developed a sturdy ethic of support for the families of Quakers who were arrested under draconian conditions of religious persecution (see Chapter 4: “Loyalty, Material Support, & Leadership”). People can take riskier (and more effective) action if they know that they and their families will be supported.

Building alternatives won’t directly bring down civilization, but as industrial civilization unravels, alternatives have two special roles. First, they can bolster resistance in times of crisis; resisters are more able to fight if they aren’t preoccupied with getting food, water, and shelter. Second, alternative communities can act as an escape hatch for regular people, so that their day-to-day work and efforts go to autonomous societies rather than authoritarian ones.

To serve either role, people building alternatives must be part of a culture of resistance—or better yet, part of a resistance movement. If the “alternative” people are aligned with civilization, their actions will prolong the destructiveness of the dominant culture. Let’s not forget that Hitler’s V2 rockets were powered by biofuel fermented from potatoes. The US military has built windmills at Guantanamo Bay, and is conducting research on hybrid and fuel-cell vehicles. Renewable energy is a necessity for a sustainable and equitable society, but not a guarantee of one. Militants and builders of alternatives are actually natural allies. As I wrote in What We Leave Behind, “If this monstrosity is not stopped, the carefully tended permaculture gardens and groves of lifeboat ecovillages will be nothing more than after-dinner snacks for civilization.” Organized militants can help such communities from being consumed.

In addition, even the most carefully designed ecovillage will not be sustainable if neighboring communities are not sustainable. As neighbors deplete their landbases, they have to look further afield for more resources, and a nearby ecovillage will surely be at the top of their list of targets for expansion. An ecovillage either has to ensure that its neighbors are sustainable or be able to repel their future efforts at expansion.

In many cultures, what might be considered an “alternative” by some people today is simply a traditional way of life—perhaps the traditional way of life. Peoples struggling with displacement from their lands and dealing with attempts at assimilation and genocide may be mostly concerned with their own survival and the survival of their way of life. And for many indigenous groups, expressing their traditional lifestyle and culture may be in itself a direct confrontation with power. This is a very different situation from people whose lives and lifestyles are not under immediate threat.

Of course, even people primarily concerned with the perpetuation of their traditional cultures and lifestyles are living with the fact that civilization has to come down for any of us to survive. People born into civilization, and those who have benefitted from its privilege, have a much greater responsibility to bring it down. Despite this, indigenous peoples are mostly fighting much harder against civilization than those born inside of it.

Every successful historical resistance movement has rested upon a subsistence base of some kind. Establishing that base is a necessary step, but that alone is not sufficient to stop the world from being destroyed.

Capacity Building and Logistics

Capacity building and logistics are the backbone of any successful resistance movement. Although direct confrontation and conflict may get the glory, no sustained campaign of direct action is possible without a healthy logistical and operational core. That includes the following:

Resistance movements of all kinds must be able to screen recruits or volunteers to assess their suitability and to exclude infiltrators. Members of the group must share certain essential viewpoints and values (either assured through screening or teaching) in order to maintain the group’s cohesion and focus.

Resisters need to be able to communicate securely and rapidly with one another to share information and coordinate plans. They may also need to communicate with a wider audience, for propaganda or agitation. Many resistance groups have been defeated because of inadequate communications or poor communications security.

Resistance requires funding, whether for offices and equipment, legal costs and bail, or underground activities. In aboveground resistance, procurement is mostly a subset of fund raising, since people can buy the items or materials they need. In underground resistance, procurement may mean getting specialized equipment without gathering attention or simply getting items the resistance otherwise would be unable to get.

Of course, fund raising isn’t just a way to get materials, but also a way to support mutual aid and social welfare activities, support arrestees and casualties or their families, and allow core actionists to focus on resistance efforts rather than on “making a living.”

People and equipment need access to transportation in order to reach other resisters and facilitate distribution of materials. Conventional means of transportation may be impaired by collapse, poverty, or social or political repression, but there are other ways. The Underground Railroad was a solid resistance transportation network. The Montgomery bus boycott was enabled by backup transportation systems (especially walking and carpooling) coordinated by civil rights organizers who scheduled carpools and even replaced worn-out shoes.

Security is necessary for any group big enough to make a splash and become a target for state intelligence gathering and repression. Infiltration is definitely a concern, but so is ubiquitous surveillance. This does not apply solely to people or groups considering illegal action. Nonviolent, law-abiding groups have been and are surveilled and disrupted by COINTELPRO-like entities. Many times it is the aboveground resisters who are more at risk as working aboveground means being identifiable.

Research and reconnaissance are equally important logistical tools. To be effective, any strategy requires critical information about potential targets. This is true whether a group is planning to boycott a corporation, blockade a factory, or take out a dam.

Imagine how foolish you’d feel if you organized a huge boycott against some military contractor, only to find that they’d recently converted to making school buses. Resistance researchers can help develop a strategy and identify potential targets and weaknesses, as well as tactics likely to be useful against them. Research is also needed to gain an understanding of the strategy and tactics of those in power.

There are certain essential services and care that keep a resistance movement running smoothly. These include services like the repair of equipment, clothing, and so on. Health care skills and equipment can be extremely valuable, and resistance groups should have at least basic health care capabilities, including first aid and rudimentary emergency medicine, wound care, and preventative medicine.

Coordination with allies and sponsors is often a logistical concern. Many historical guerilla and insurgent groups have been “sponsored” by other established revolutionary regimes or by states hoping to foment revolution and undermine unfriendly foreign governments. For example, in 1965 Che Guevera left postrevolutionary Cuba to help organize and train Congolese guerillas, and Cuba itself had the backing of Soviet Russia. Both Russia and the United States spent much of the Cold War “sponsoring” various resistance groups by training and arming them, partly as a method of trying to put “friendly” governments in power, and partly as a means of waging proxy wars against each other.

Resistance groups can also have sponsors and allies who are genuinely interested in supporting them, rather than attempting to manipulate them. Resistance in WWII Europe is a good example. State-sponsored armed partisan groups and other partisan and underground groups supported resistance fighters such as those in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Direct Conflict and Confrontation

Ultimately, success requires direct confrontation and conflict with power; you can’t win on the defensive. But direct confrontation doesn’t always mean overt confrontation. Disrupting and dismantling systems of power doesn’t require advertising who you are, when and where you are planning to act, or what means you will use.

Back in the heyday of the summit-hopping “antiglobalization” movement, I enjoyed seeing the Black Bloc in action. But I was discomfited when I saw them smash the windows of a Gap storefront, a Starbucks, or even a military recruiting office during a protest. I was not opposed to seeing those windows smashed, just surprised that those in the Black Bloc had deliberately waited until the one day their targets were surrounded by thousands of heavily armed riot police, with countless additional cameras recording their every move and dozens of police buses idling on the corner waiting to take them to jail. It seemed to be the worst possible time and place to act if their objective was to smash windows and escape to smash another day.

Of course, their real aim wasn’t to smash windows—if you wanted to destroy corporate property there are much more effective ways of doing it—but to fight. If they wanted to smash windows, they could have gone out in the middle of the night a few days before the protest and smashed every corporate franchise on the block without anyone stopping them. They wanted to fight power, and they wanted people to see them doing it. But we need to fight to win, and that means fighting smart. Sometimes that means being more covert or oblique, especially if effective resistance is going to trigger a punitive response.

That said, actions can be both effective and draw attention. Anarchist theorist and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin argued that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.”30 The intent of the deed is not to commit a symbolic act to get attention, but to carry out a genuinely meaningful action that will serve as an example to others.