by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 19, 2017 | Education, Movement Building & Support

by Erin Moberg / Deep Green Resistance Eugene

On Saturday, February 4th, several members of DGR Oregon attended a day-long NVDA training in Eugene, Oregon. The event was organized by local and regional activists. Over 200 people attended, including local activists, community members new to direct action, college students, youth, retired people, and others from nearby towns.

DGR members attended this training as part of an increased effort to connect with Eugenians from other activist groups and to invite community members to two upcoming events: (1) a DGR Open House in downtown Eugene (March 8) and (2) an Advanced Direct Action Training to be held just outside of Eugene over Earth Day weekend (April 22-23). We also, of course, wanted to see what we could learn.

The Keynote Speaker was Leonard Higgins, who shared a short film documenting his experience as one of the “valve turners” who shut down oil pipelines in five states in October of 2016. Higgins described direct action as “not the only important work to be done” but crucial in that it supports other activist work, including: changing the economy, transitioning to alternative energies, and expanding community organizing strategies. Although his remarks and the entire training focused on “preserving life as we know it and civilization” and “ensur[ing] a future for human civilization,” Higgins and the film did help to normalize and demystify direct action for those new to environmental activism.

People who want to support the valve turners can attend a legal costs fundraiser event on the evening of February 24th at 6:30pm at the First Methodist Church near downtown Eugene. The suggested donation for the event is $20, but no one will be turned away for lack of funds.

The workshops (Medic Training, Encryption Basics, Jail/Arrest Support, Action Planning, “Artivism,” and more) emphasized peaceful resistance toward the end of sustaining or bettering life for human beings. Even when referencing the Water Protectors at Standing Rock, there was no concrete mention of the destruction of the land and little reference to the occupation of indigenous communities and territories by the culture of empire. While this may be simple omission, it’s a trend in mainstream activist groups—especially in predominantly white groups—to avoid naming the problem, and to avoid being “negative.”

Most frustrating in the workshops was the lack of organization and structure; many facilitators had poor presentational skills, little understanding of key semantic nuances of relevant terminology (ie: violence, use of protective force, and violation), and an overall lack of consciousness around anti-oppression strategies necessary to foster equitable engagement and collaborative environments.

This is unsurprising, as in our experience mainstream activist groups and NGOs such as this often serve as a sort of buffer against truly revolutionary change by funneling energy, donations, and volunteers into minor reforms.

In the workshop on Action Planning, the facilitator (a Portland-based activist) did share several strategies that could be useful for DGR meetings, direct action trainings, and forum culture. One is the acronym WAIT/WAINT (Why Am I Talking? / Why Am I Not Talking?), a variant of the Step Up/Step Back framework designed to encourage those who occupy positions of privilege and tend to dominate (white people, men, documented folks, etc.) to hold space for those whose voices and experiences are often silenced or ignored (people of color, women, undocumented folks, etc.). She also explained the “Points of Intervention Model” as way for activists to identify how, where, and when to plan a concrete direct action. This model asks organizers to consider points of production (ie: labor site), destruction (ie: mines), consumption (ie: households), decision (ie: corporate head), assumption (ie: segregated spaces), and potential before then deciding on:

- vision –> (2) campaign–> (3) strategy–> (4) tactic–> (5) action

Her example was:

- Stop climate change–> (2) Halt proposed pipeline construction–> (3) pass anti-pipeline legislation–> (4) forums, petitions, lawsuits–> (5) Not specified during the workshop

While the training was a good first step for first-time activists interested in learning more about political organizing, this day of workshops didn’t provide a compelling vision of the application of political power. For those with little to no activist experience, there were no clear articulations of the history, potential, and goals of direct action. For those who attended as experienced activists, there were no hands-on workshops offered for specific direct action skills trainings (ie: how to build and use lockboxes). The legal presentations, encryption info, and medic training did offer concrete skills that are valuable to organizers. In terms of community representation at this event, there were no facilitators of color, few female facilitators, and few opportunities designed to connect training participants one-on-one.

Overall, this training focused on issues leading up to or arising in the aftermath of direct actions, not the actions themselves. For organizing large groups to achieve reforms, it was a potentially useful training. However, for people interested in deep revolutionary changes, it was lacking.

Thanks to the organizers for hosting this event.

People interested in learning more advanced skills should contact DGR Eugene to inquire about our advanced direct action training scheduled for Earth Day weekend, April 22-23.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 18, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health, Human Supremacy, Listening to the Land

Featured image: Mauna Loa, night time view (Photo: Rustedstrings/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

So many indigenous people have told me that the levels of sustainability their traditional cultures achieved prior to the arrival of colonizers were based on lessons learned from non-humans. Implicit in these lessons is the truth that humans depend on non-humans. This dependence is not limited to the air we breathe, the water we drink, or the food we eat. This dependence sinks into our very souls.

For many indigenous people I have listened to, the basic reality of human dependence demands that humans regard non-humans, regard life, regard the universe with deep humility.

If we simply learn to listen, we will hear non-humans demonstrating humility everywhere. Trees know they are nothing without soil, so they build forests as monuments to soil health – collecting, storing, and restoring nutrients to their life-giver. Salmon know they are nothing without forests to hold river banks together, so they swim deep into the cold oceans to feed, bring their bodies back upriver to die, and, in death, feed the forests. Phytoplankton know they are nothing without a climate that allows warm and cold ocean waters to mix, producing currents that bring them their food. So, phytoplankton feed the salmon that feed the forests that store carbon that has the potential to destroy the climate that feeds the phytoplankton.

Approach non-humans with humility, and you may find them willing to teach you.

******

It was the stars who put me in my place. I know this, locating myself in my memories of cold nights in the open air and my sleeping bag, watching the clear sky from the shoulders of sacred Mauna Kea in Hawai’i. I rest north to south. The Southern Cross sits low on the horizon, just above the outline of my toes warmly wrapped in down. I arch my back and look high above me where Polaris holds the sky steady. To my right, the sun pulled the darkness over like blankets on a bed and fell asleep. In the space between Venus and Orion’s Belt, there are more shooting stars than I have wishes. To my left, a faint anxiety grows. When the sun wakes, its siblings – the stars – will disappear.

“I” diminish in these moments. My mind quiets and and there are only the gifts the stars give.

Stars are so fundamental to our existence they give us the ability to contemplate the process that allows us to perceive them. Perhaps, this is why stars are so beautiful. When we view them, we see the beginning of everything.

Stars are the oldest nuclear reactors. The gases they burn produce energy at such great magnitudes they are visible on Earth from hundreds of thousands of lightyears away. They burn like this for time unfathomable until they die in great explosions. When stars explode, the violence alters hydrogen and helium to shower the universe with materials like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, iron, and sulfur. These materials are the basis of life.

Stars give me the ability to experience. I can experience because I have a body. The elemental showers dying stars produce have organized- first as neutrons and protons, then as atoms, and finally as air, water, soil, stone, and flesh – to form my body. But, stars don’t form only human bodies, they form bones, fur, and fins; skin, scales, and exoskeletons; mountains, oceans, and the sky.

Stars give the universe the first wisdom: For there to be life, there must be death. After a life spent in service as a sun, warming a community of planets, a star dies. It is a violent death – a death that destroys a solar system. But, it is a necessary death. A death that transforms the old into a possibility for the new.

******

My last essay in this ecopsychology series “The Destruction of Experience: How Ecopsychology Has Failed” generated some curious responses from, specifically, ecopsychologists and ecotherapists. Many of them were provoked to defensiveness, denial, or both by my words. In fact, one commentator Thomas J. Doherty, a psychotherapist, was moved to write an essay for the San Diego Free Press where he characterized my report of the failure of ecopsychology as “greatly exaggerated.”

The responses suggest that some of my readers felt like I was attacking their life’s work. Of course, I was. Ecopsychologists, however, need not feel alone in their failure. With the destruction of the planet intensifying at an ever-faster pace, we are all failing.

As I’ve sought to understand the responses I received, I’ve realized that many students of ecopsychology employ a different definition of “success” than I do. Quite simply, their definition is infected with human supremacism.

One way to understand the difference is to ask: Would extinct species characterize reports of the failure of ecopsychology as “greatly exaggerated?” Would Pinta Island Tortoises, Pyrenean Ibexes, Falklands Wolves, Rocky Mountain Lotuses, Great Auks, Passenger Pigeons or any of the 200 species that were pushed to extinction yesterday, the 200 species that were pushed to extinction today, or the 200 species that will be pushed to extinction tomorrow characterize reports of the failure of ecopsychology as “greatly exaggerated”?

Lonesome George Pinta giant tortoise Santa Cruz (Source: putneymark/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0)

******

What is human supremacism?

In his 2016 book The Myth of Human Supremacy, Derrick Jensen coined the term “human supremacism” and gave human animals the analysis we so badly need to understand the murder of our non-human kin.

Human supremacism is a system of power in which humans dominate non-humans to derive material benefit. Agriculture is a classic result of human supremacism Agriculture requires clearing the land of every living being in order to plant and harvest a single crop which is then used to feed humans.

Human supremacism makes the fossil fuel industry possible. To produce electricity, to fuel cars, planes, and ships, to produce fertilizers for their crops, humans poison water, rip the tops off mountains, carve scars into landscapes, and fundamentally alter the climate. Even so-called “green energy” is produced by humans dominating non-humans as fragile desert ecosystems are destroyed for wind farms, rivers are dammed for hydroelectricity, and the land is gutted for metals and minerals like copper and aluminum to be used in solar panels.

The power humans have gained over non-humans is rooted in human supremacists’ maintenance of a monopoly of the means of violence over non-humans and their human allies who dare to challenge human supremacism.

The history of wolf-hunting in civilized nations, as just one example, demonstrates this monopoly. Despite centuries of demonization, wolves pose little direct threat to humans. However, when agriculture encroaches on the homes of wolves’ traditional prey causing these species’ populations to collapse, wolves will eat domesticated animals. Human supremacists throughout history have responded with wolf extermination campaigns. The extinction of so many wolf species while many other wolf species tinker on the edge of extinction is testament to the wrath of human supremacism.

Deep ecologist, Neil Evernden, pointed out that scientists in vivisection labs cut the vocal cords of the animals they experiment on. If humans heard the screams of their non-human kin, they would not murder them. Human supremacism takes this practice to the psychological level. You can physically cut the vocal cords of individual non-humans you plan to torture. Or, you can achieve a total silencing of the non-human world if you convince whole human societies that non-humans are incapable of communicating, incapable of screaming, incapable, even, of feeling pain.

Human supremacism cuts the vocal cords of the non-human world, and achieves this silencing, by developing cultural myths teaching that non-humans are “resources” to be used by humans. Living forests are no longer living forests; they are so many square feet of board lumber. Wild rivers are no longer wild rivers; they are so many cubic meters of water. Old-growth prairies are no longer old-growth prairies, they are so many acres of tillable farmland.

Another myth human supremacism propagates is the notion that humans are superior to everyone else. Because humans are superior, human domination of non-humans is completely justified and natural. Jensen shows how strongly humans cling to this sense of superiority. He writes, “Human supremacists – at this point, almost everyone in this culture – have shown time and again that the maintenance of their belief in their own superiority, and the entitlement that springs from this belief, are more important to them than the well-being or existences of everyone else.”

Human supremacists cannot tolerate anyone who reminds them of the insanity of human supremacy. They systematically annihilate traditional cultures and indigenous peoples with sustainable cultures based on human humility. Despite their best efforts to silence the non-human world, on a fundamental level the task is impossible and human supremacists come to hate non-humans for refusing to die quietly. And no one dies quietly. Human supremacists hate the reminders, so they must destroy the reminders, and in the destruction they are reminded again. If we do not stop human supremacists, their vicious cycle will only end when there is total silence.

******

The responses I received for daring to suggest that ecopsychology has failed reveal that the maintenance of human supremacism is more important to many ecopsychologists than ensuring the survival of life on earth.

Let me be clear: There are positive trends within ecopsychology. At its best, ecopsychology uncovers the connection of human souls to the soul of the world, illustrates human dependence on the non-human, and demands effective action to protect the soul of the world and the non-humans we depend on. At its worst, ecopsychology privileges human psychological health at the expense of non-humans, seeks to use the natural world to promote false feelings of peace, becomes an anesthetic in the face of planetary collapse, and is infected with insidious human supremacy.

Ecopsychology’s human supremacist infection is as understandable as it is unforgivable. All of us born into the dominant culture have been indoctrinated to the central tenets of human supremacism. Radical psychologist R.D. Laing, who spent a brilliant career trying to understand how we arrived at a moment where humans were empowered to destroy the planet through forces like thermonuclear war, explained how deeply this indoctrination runs. He wrote, “Long before a thermonuclear war can come about, we have had to lay waste our own sanity. We begin with the children. It is imperative to catch them in time. Without the most thorough and rapid brainwashing their dirty minds would see through our dirty tricks. Children are not yet fools, but we shall turn them into imbeciles like ourselves with high I.Q.s if possible.”

Despite these high I.Q.s that even good-hearted ecopsychologists are equipped with, human supremacism is so entrenched that it is almost invisible. On his way to ripping the mask off human supremacism, Jensen wrote in his study of hatred The Culture of Make Believe that “hatred felt long and deeply enough no longer feels like hatred, but more like tradition, economics, religion…” And, when ecopsychologists place the primacy of human mental, emotional, spiritual, and even, physical health over the continued existence of forests, mountains, rivers, non-human species, and the planet’s capacity to support life, we must extend Jensen’s idea to conclude: Hatred felt long and deeply enough no longer feels like hatred, it feels like ecopsychology.

Too many ecopsychologists, ecotherapists, and so-called environmentalists spend the vast majority of their time devising means to promote human mental health and feelings of peace, hope and acceptance through phenomena like what Doherty calls in his essay “nature contacts.”

Reducing non-humans to “nature contacts” objectifies them. Human supremacist ecopsychologists view living forests as therapy tools. They view rivers as anti-depressants. When humans view forests and rivers as objects to use to gain mental health, they act like men who view women as objects to use for sexual gratification, and white people who view people of color as objects to use for economic benefit.

But, living forests and wild rivers live for themselves.The world is not filled with “nature contacts.” It is filled with aspen groves, great-horned owls, elk, black bears, pinyon-juniper forests, rainbow trout, this smooth blue pebble, that red rock canyon, a particular wisp of fog moving through sage brush. In short, the world is filled with living beings who exist for their own purposes that you and I may never understand.

Ecopsychologists demonstrate where their concern lies through their actions, or what they actually do in their day-to-day lives. When students of ecopsychology are more concerned with how the natural world improves human mental health than they are with the murder of the natural world, they are acting as human supremacists. When their day-to-day lives are spent leading “wilderness immersion trips” for the sake of healing human minds while that very wilderness is threatened with human-induced collapse, they are acting as human supremacists. When their day-to-day lives are spent in the clinic office helping clients “cope” and “adjust to” the insanity of civilized culture while that culture threatens the existence of life on earth, they are acting as human supremacists.

******

I am writing this series because I know there are students of ecopsychology who want to wield ecopsychology’s insights to make the environmental movement more effective, as I do. But to do this, we must be willing to take an honest assessment of ecopsychology that goes beyond human health, to the health of the natural world.

Exploring the different definitions of ecopsychological success helps us make this assessment. It is only possible to consider ecopsychology a success if you subscribe to a liberal, human supremacist worldview.

The human supremacist definition of success begins with what appears, at first glance, to be a series of obvious conclusions. First, human actions are causing planetary collapse. and humans actions flow from human psyches. So, it follows that changing human psyches is the path to stopping planetary collapse. For human supremacist ecopsychologists, planetary collapse is a tragedy, but it is a tragedy for the trauma it causes humans.

While I have no problem with the conclusion that human psyches need to change, I do have a problem with the means liberal ecopsychologists think will achieve this change. Most people on the Left attach positive connotations to “being liberal” and may be surprised by my criticism of the liberal worldview. Nevertheless, one reason planetary collapse is intensifying is the failure of the Left to forsake liberalism for a radical analysis.

The brilliant author Lierre Keith has devised an accurate articulation of the liberal worldview. She explains that, for liberals, the basic social unit is the individual. For liberals, individuals can be understood separate from the social environment constructing them. Liberals believe that attitudes are the sources and solutions of oppression, that pure human thought is the prime mover of social life, and, therefore, education and rational argument are the best engines for social change.

Liberal, human supremacist ecopsychology, because it embraces the notion that the basic social unit is the individual, focuses on healing human psyches one individual at a time. Because liberal ecopsychologists obsess over human thought as the primary culprit in psychopathology, they insist that individual education and rational argument are the best ways to heal widespread, cultural psychopathology. The prevalence of ecotherapy, whether its the healing of individuals in the clinic office, on wilderness immersion trips, or simple talk-therapy sessions conducted outside, is the result of a liberal belief that individual education will save the world.

The liberal, human supremacist worldview allows for ecopsychological success to be achieved on a personal and individual level. For liberal ecopsychologists every person, who alleviates depression with walks in a forest, or engages in grief work to come to acceptance of mass extinction, or finds a personal sense of joy amidst the destruction, is a success.

******

My definition of success, on the other hand, is biocentric and radical. A biocentric definition of ecopsychological success recognizes that non-humans have souls, too, that human souls and non-human souls are expressions of Life’s soul. And, with these souls, comes a right to exist on their own terms. Humans are responsible for planetary collapse and changing human psyches is necessary to stop the collapse. But, the biocentric definition of success recognizes that the human psyche is fundamentally dependent on relationships with non-humans. So, the development of healthy human psyches requires, before anything else, a healthy biosphere.

My definition is also radical. Though most people misunderstand “radical” to mean “extreme,” radical simply means “getting to the roots.” For radicals, “getting to the roots” means understanding, and then dismantling, oppressive power structures on a global level. As part of this, radicals see groups and classes as the basic social unit. An individual’s group or class socially constructs the psyche. Most importantly, radicals understand that material power – the physical ability to coerce – is the prime mover of society. Social change, then, requires organized resistance geared at wielding power.

While I am very happy for individuals with access to existent natural communities who alleviate their mental illnesses through ecotherapy, these individual victories will be more and more difficult to come by so long as more and more natural communities are destroyed. As natural communities are destroyed, rates of human psychopathology will accelerate. Humans will become evermore insane while they cause ecological collapse and, causing ecological collapse, they ensure the impossibility of the physical survival of life.

Liberalism – with its individualism – and human supremacism – with the narcissism it facilitates in the human species – encourages ecopsychologists to ask “What can I do?” This question is no longer adequate. A biocentric, radical analysis pushes us beyond asking “What can I do?” to ask: “What needs to be done?”

More than just human individuals need to be saved. Human cultures where widespread psychopathology is impossible need to be created. To achieve these cultures requires dismantling the power structure causing ecological collapse, the power structure crushing sustainable cultures, and the power structure thwarting efforts to recreate sustainable cultures. Civilization – defined as a culture resulting from and producing humans living in populations so dense they require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life – is this power structure.

Civilization must be dismantled. This will not be achieved in the mind. Civilization is not an emotional state. It is not a misunderstanding. It will not be cured with rational argument.

Civilization is maintained by force. Men with guns and bombs ensure that business is conducted as usual. These guns and bombs give human supremacists power. They give human supremacists the ability to coerce everyone else. Human supremacists gain their guns and bombs, the physical force they require to protect civilization, through destruction of natural communities. Guns and bombs require mines, pipelines, and factories and the pollution mines, pipelines, and factories produce. To deprive human supremacists of their power requires depriving human supremacists of their physical ability to exploit natural communities. It requires dismantling mines, pipelines, and factories.

The question is, what are we waiting for?

******

In the end, we are waiting for death. This death can be psychological. We can let the misguided hope in ineffective tactics die. We can let the mistaken belief that human well-being on a collapsing planet is possible die. We can let the insane insistence that we are more valuable than non-humans die.

Or, all of us will die.

I return to the stars. The stars illuminate our radical dependence on the non-human world for our existence. The stars teach that death brings new life. Death can be painful. I’m sure the death of a star, and the incineration of a solar system, is incredibly painful. But, after the pain, after the death of the old, a new life begins. Human supremacism must die, so a new human humility can begin.

Will Falk moved to the West Coast from Milwaukee, WI where he was a public defender. His first passion is poetry and his work is an effort to record the way the land is speaking. He feels the largest and most pressing issue confronting us today is the destruction of natural communities. He received a Society of Professional Journalists, San Diego Chapter, 2016 Journalism award. He is currently living in Utah.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Derrick Jensen

When I find myself in times of trouble, I’m less interested in Mother Mary’s wisdom than I am in Joe Hill’s: Don’t mourn; organize.

There’s a sense in which Trump’s election is a surprise, similar to how we somehow seem to be continually surprised when easily predictable negative consequences of this way of life come to pass. So we’re surprised when bathing the world in insecticides somehow causes crashes in insect populations, when covering the world in endocrine disrupters somehow leads to the disruption of endocrine systems, when damming and dewatering rivers somehow kills the rivers, when murdering oceans somehow murders oceans, when colonialism somehow destroys the lives of the colonized, when capitalism somehow destroys communities and the natural word, when rape culture somehow leads to rape, and so on. And we’re surprised when a racist, woman-hating culture elects a racist man who hates women.

But there are also many senses in which the rise of Trump or someone very like him was entirely predictable.

An empire in decay leads to a desperate push to the fore of values manifested by Trump: woman-hatred, racism, the scapegoating of those who impede empire, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to maintain that empire, to “make America [Greece, Rome, Britain, China] great again.”

When those who have been able to exploit others with impunity find their way of life (and more to the point, the exploitation and entitlement upon which their way of life is based) crumbling, what do they do?

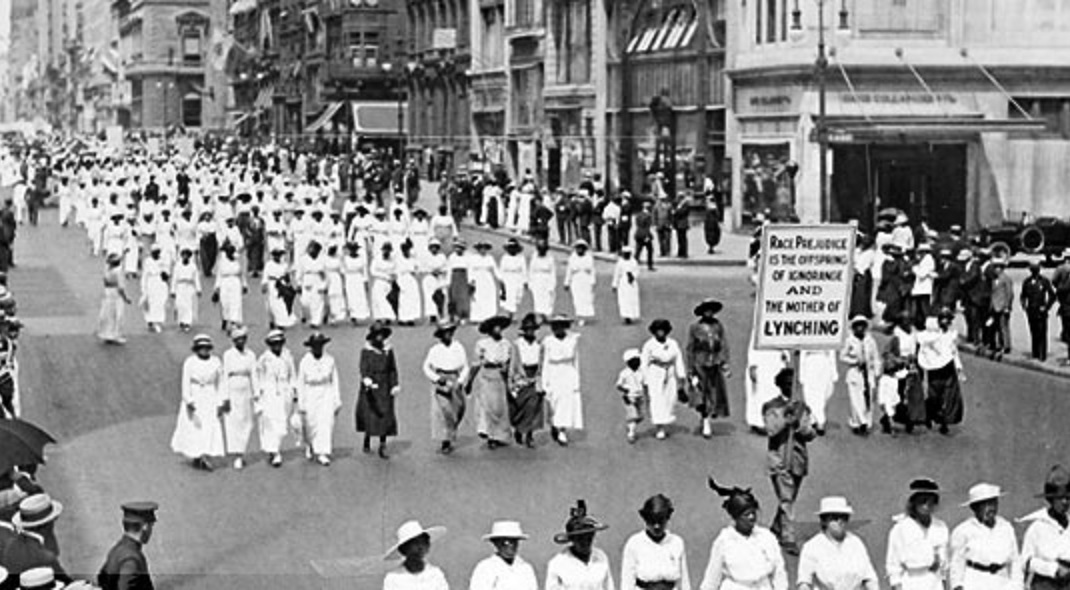

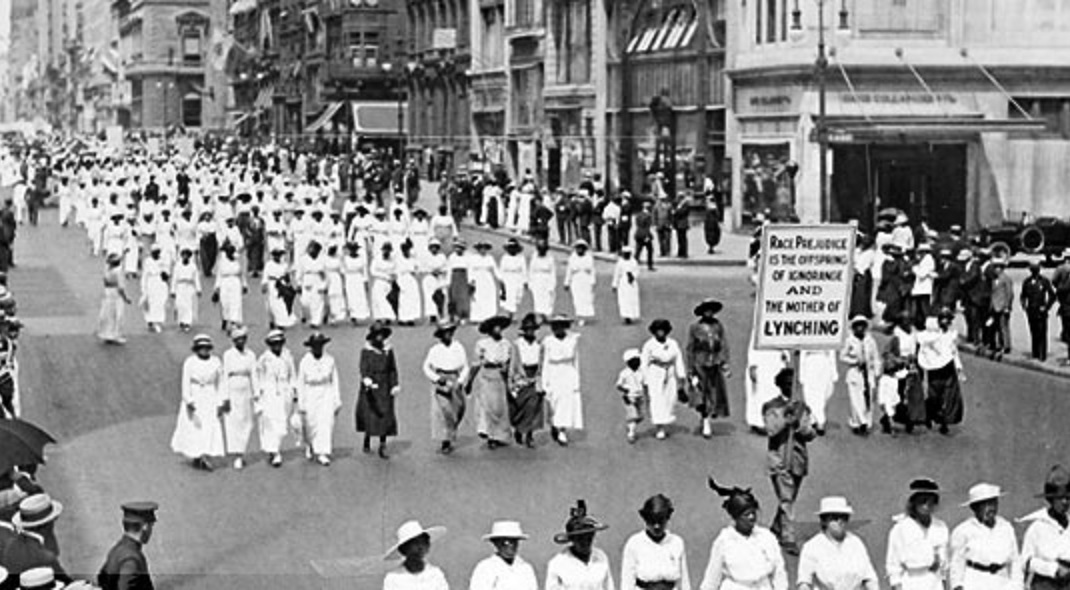

We’ve seen this before. Why did lynchings of African-Americans go up soon after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery? Why did the KKK rise again in the 1910s and 1920s? What is the relationship between Germany’s economic collapse in the 1920s and the rise of Nazi fascism?

Nietzsche provides one answer: “One does not hate when one can despise.”

So long as one’s exploitation of others proceeds relatively smoothly, one can merely despise those one exploits (despise, from the root de-specere, meaning to look down upon). So long as I have unfettered access to the lives and labor of, say, African-Americans, everything is, from my perspective, A-Okay. But impinge in any way on my ability to exploit, and watch the lynchings begin. The same is true for my access to other so-called resources as well, whether these “resources” are “timber resources,” “fisheries resources,” cheap plastic crap from China, or sexual and reproductive access to women. So long as the rhetoric of superiority works to maintain the entitlement, hatred and direct physical force remain underground. But when that rhetoric begins to fail, force and hatred waits in the wings, ready to explode.

Oh, but we wouldn’t do that, would we? Well, what if someone told you that no matter how much you paid to purchase title to some piece of land, the land itself does not belong to you. No longer may you do whatever you wish with it. You may not cut the trees on it. You may not build on it. You may not run a bulldozer over it to put in a driveway. Would you get pissed? How if these outsiders took away your computer because the process of manufacturing the hard drive killed women in Thailand. They took your clothes because they were made in sweatshops, your meat because it was factory-farmed, your cheap vegetables because the agricorporations that provided them drove family farmers out of business, and your coffee because its production destroyed rain forests, decimated migratory songbird populations, and drove African, Asian, and South and Central American subsistence farmers off their land. They took your car because of global warming, and your wedding ring because mining exploits workers and destroys landscapes and communities. Imagine if you began losing all of these parts of your life that you have seen as fundamental. I’d imagine you’d be pretty pissed. Maybe you’d start to hate the assholes doing this to you, and maybe if enough other people who were pissed off had already formed an organization to fight these people who were trying to destroy your life—I could easily see you asking, “What do these people have against me anyway?”—maybe you’d even put on white robes and funny hats, and maybe you’d even get a little rough with a few of them, if that was what it took to stop them from destroying your way of life. Or maybe you would vote for anyone who promised to make your life great again, even if you didn’t really believe the promises.

The American Empire is failing. Real wages have been declining for decades, for the entire lifetime of most people living today in the U.S. Indeed if real wages peaked in 1973, the last of those who entered the workforce in a time of universally increasing expectations are retiring. Sure, some sectors of the economy have done well, but what of those left behind? What of those whose livelihoods have been destroyed by a globalized economy, by the shifting of jobs to China, Vietnam, Bangladesh?

What happens to people in a time of declining expectations? What is the relationship between these declining expectations and the rise of fascism?

Two decades ago now a long-time activist said to me that Walmart and its cheap plastic crap was the only thing standing between the United States and a fascist revolution.

But cheap plastic crap can only put off fascism for so long.

There’s a difference between the ends of previous empires and the end of the current empire. That difference is global ecological collapse. Empires are always based not only on the exploitation of the poor but on the existence of new frontiers. Any expanding economy–and all empires are by definition expanding economies—need to continue expanding or collapse. America grew because there was always another ridge to cross with another forest to cut on the far side, always another river to dam, another school of fish to find and net. And the forests are gone. The rivers are gone. The fish are gone. The pyramid scheme upon which both civilization and more recently capitalism are based has reached its endgame.

And rather than honestly and effectively addressing the predicament into which not only we ourselves but the world has been pushed, it’s far easier to lie to ourselves and to each other. For some—and Democrats generally choose this lie—the lie can be that despite all evidence, capitalism need not be destructive of the poor and of the natural world, that the “invisible hand of Adam Smith” can, as Bill Clinton put it, “have a green thumb.” We just have to do capitalism nicely. And another lie—this one more favored by Republicans and manifested by Trump—is that the sources of our misery do not inhere in capitalism but rather come from Mexicans “stealing our jobs” and not remembering their proper place, from women no longer remembering their proper place, from African Americans no longer remembering their proper place. Their proper place of course being in service to us. And of course those damn environmentalists—“Enviro-Meddlers,” as some call them—are to blame for denying us access to that last one percent of old growth forest, that last one percent of fish. This lie blames anyone and anything other than the end of empire.

All of which brings us to the Democrats’ responsibility for Trump’s election. There has not been a time in my adult life—I’m 55—when Democrats have maintained more than the barest pretense of representing people over corporations. Through this time Democrats have functionally played good cop to the Republicans’ bad cop, as Democrats have betrayed constituency after constituency to serve the corporations that we all know really run the show. For generations now Democrats have known and taken for granted that those of us who care more for the earth or for justice or sanity than we do increased corporate control will not jump ship and support the often open fascists on “the other side of the aisle,” so these Democrats have calmly sidled further and further to the right.

Bad cop George Bush the First threatened to gut the Endangered Species Act. Once he had us good and scared, in came good cop Bill Clinton, who did far more harm to the natural world than Bush ever did by talking a good game while gutting the agencies tasked with overseeing the Act. Clinton, like any good cop in this farcical play, claimed to “feel our pain” as he rammed NAFTA down our throats.

What were we going to do? Vote for Bob Dole? Not bloody likely.

Obama made a big deal of delaying the Keystone XL as he pushed to build other pipeline after other pipeline, and as he opened up ever more areas to drilling. He pretended to “wage a war on coal” while expanding coal extraction for export.

What were we going to do? Vote for Mitt Romney?

For too long the primary and often sole argument Democrats have used in election after election is, “Vote for me. At least I’m not a Republican.” And as terrifying as I find Trump, Giuliani, Gingrich, Ryan, et al, this Democratic argument is not sustainable. Fool me five, six, seven, eight times, and maybe at long last I won’t get fooled again.

What we must finally realize is that the good cop act is, too, simply an act, and that neither the good cops nor the bad cops have ever had our interests at heart.

The primary function of Democrats and Republicans alike is to take care of business. The primary function is not to take care of communities. The primary function is not to take care of the planet. The primary function is to serve the interests of the owning class, by which I mean the owners of capital, the owners of society, the owners of the politicians.

We have seen over the last couple of generations a consistent ratcheting of American politics to the right, until by now our political choices have been reduced to on the one hand a moderately conservative Republican calling herself a Democrat, and on the other a strutting fascist calling himself a Republican. If we define “left” as being at minimum against capitalism, there is no functional left in this country.

For all of these reasons the election of Trump is no surprise.

But there’s another reason, too. The US is profoundly and functionally racist and woman-hating, nature hating, poor hating, and based on exploiting humans and nonhumans the world over. So why should it surprise us when someone who manifests these values is elected? He is not the first. Andrew Jackson anyone?

If that activist was right so many years ago, that cheap plastic crap from Walmart was the only thing standing between us and fascist revolution (and of course this cheap plastic crap merely pushed this social and natural destructiveness elsewhere) then he had to know also that cheap plastic crap is not a long term bulwark against fascism. It can only keep those chickens at bay for so long before they come home to roost.

The good cop/bad cop game is a classic tool used by abusers. You can do what I say, or I can beat you. You can sell me your cotton for 50 cents on the dollar, or I can hang you on a tree next to the last black man who refused my offer. Germans offered Jews the choices of different colored ID cards, and many Jews spent a lot of energy trying to figure out which color was better. But the whole point was to keep them busy while convincing them they held some responsibility for their own victimization.

I’ve long been guided by the words of Meir Berliner, who died fighting the SS at Treblinka, “When the oppressors give me two choices, I always take the third.”

By choosing the third I don’t mean simply choosing a third party candidate and perceiving yourself as pure and above the fray, as capitalism still continues to kill the planet.

I mean recognizing the truths about this whole exploitative, unsustainable, racist, woman-hating system. Recognizing that the function of politicians in a capitalist system is to act very much like human beings as they enact what is good for capital, as they facilitate, rationalize, put in place, and enforce a socio-pathological system. Recognizing that capital—including the functionaries of capitalism called “politicians”—will not act in opposition to capital because it is the right thing to do. These functionaries will not act in opposition to capital because we ask nicely. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism impoverishes the poor worldwide. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism is killing the planet. They will not act in opposition to capital. Period.

The power they wield, and the way they wield it, is not a mistake. It is what capitalism does.

Which brings us to Joe Hill. Don’t simply complain about Trump. Don’t simply throw up your hands in despair. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that the good cops would, if just unhindered by those bad cops, do the right thing or act in your best interests. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that capitalists will act other than they do. And certainly don’t take for granted that somehow magically we and the world will get out of this predicament, that somehow magically an anti-capitalist movement will spontaneously generate, or an anti-racist movement, a pro-woman movement, a movement to stop this culture from killing the planet. These movements emerge only through organized struggle. And someone has to do the organizing. Someone has to do the struggling. And it has to be you, and it has to be me.

A doctor friend of mine always says that the first step toward cure is proper diagnosis. Diagnose the problems, and then you become the cure.

You make it right.

So what I want you to do in response to the election of Donald Trump is to get off your butt and start working for the sort of world you want. Don’t mourn the election of Trump, organize to resist his reign, and organize to destroy the stranglehold that the Capitalist Party has over political processes, the stranglehold that capitalists and racists and woman-haters have over the planet and over all of our lives.

For more of Derrick Jensen’s analysis of racism, hatred, and the violence of civilization, see his book The Culture of Make Believe

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 14, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I do not remember the first time I saw my mother’s face, though I know she remembers the first time she saw mine. It was the very beginning of my life, my birth. I do not remember the first time I saw my mother’s face, but, I do remember the first time I saw my mother’s face at what would have been the end of my life after I tried to kill myself.

This is what I’m thinking about as I hold my fifteen-month-old baby nephew Thomas while he falls asleep.

A soft darkness blankets the room. The curtains are tied back on either side of the room’s only window and the night pours in. A wet snow falls with the starlight in a sprinkling of silver and gray. A few nights before full and the moon is strong. Shadows flicker on the floor below the window. A pine whispers outside where the wind brushes powder from her branches.

His head is nestled between my chest and shoulder. I lean back into a wide chair, careful not to let my elbow bump the armrest and jostle Thomas’ little head. Thomas’ eyes are open as he watches the snow fall with me. In the spaces between the clouds, the sky is revealed as a deep blue. The moon’s glow gently pulls the blue down where it settles as the same color in Thomas’ eyes.

The snow sets a contemplative rhythm. As the flakes grow and the snow slows, Thomas’ eyelids become heavier until his eyes no longer stay open. I cannot decide whose rest is more peaceful: Thomas’ or the snow’s. In the stillness, holding Thomas close, I feel two heartbeats. Mine is slower and heavier, while Thomas’ is gentler, quicker. Once in a while, the beats sync together and it feels like a chord plucked far away strikes us gently, runs through us, and echoes on.

Outside, the falling temperature is indicated by fog growing on the corners of the window. Inside, I feel the familiar warmth that grows in my chest whenever I hold Thomas. It’s not just Thomas’ small heat emanating through his pajamas and his favorite blanket into my body.

The warmth’s source is gratitude. Holding Thomas like this, listening to the smallness of his breaths and the gentleness of his heartbeat, I recognize the way Thomas is wholly dependent on those who love him for his life. First, his body was nurtured for nine months in his mother’s body. After his birth, he required his mother’s milk for sustenance. As he grows, he needs his mother, his father, and all those who love him to feed him, to clothe and bathe him, to provide shelter, to attend to any illness he experiences, and to make sure he has hands to fall into now that he climbs everything his strength will allow. Right now, he needs me to provide his nightly bottle, to hold him close and steady as he falls asleep, and then to lay him down in his crib.

Thomas teaches me about my own dependence. The warmth I experience holding Thomas bonds me to him. This connection makes threats to his well-being threats to my own. If he is hurt, I will be hurt, too. Feeling this warmth and understanding the connection forming, I feel I am participating in an ancient emotional ritual. One of the circles of life is completed in this experience. I know, now, what my mother must have felt holding me. The humility in the feeling is staggering.

I wish nothing would ever disturb this little creature asleep in my arms. I wish he could live his whole life laughing like he does when his hands find a new texture they’ve never experienced before. I wish he could live his whole life the way he dances in a style completely lacking self-consciousness anytime music becomes audible. I wish he could live his whole life confident that a loved one will envelop him in a sincere embrace whenever he reaches out for one.

There is horror in my wish. I know no one who has ever loved a child could guarantee the child’s total safety. But, in today’s world where we are poisoning our water, making our air nearly unbreathable, burning our soil at dizzying paces, and irreversibly altering our climate, children born today may find their homes unlivable when they reach my age. In fact, generations of children born in the colonies and sacrifice zones have already found their homes unlivable.

I think back to the worst two days of my life. They weren’t the two days I tried to kill myself. They were the two days after when I sat across from my mother, trying to meet the sky’s dusk blue in her eyes, while I explained to the woman who sacrificed so much to give me life why there was nothing more she could have done to prevent me from trying to take that life.

While I am holding Thomas, I cannot stop the visions of his future from forming. Feeling the love I feel for him right now, I cannot imagine the pain I would feel if he sat across from me, head bent under the invisible weight of despair, as he explained how there was nothing I could have done to stop the major depression he experiences. And in my memories of my mother and visions of Thomas’ potential future, I recognize the truth: Even if we succeed in keeping our children physically safe, in this time of ecological collapse we cannot shield their souls from the psychological effects of the destruction.

My nephew, Thomas. Photo by Paula Bradley.

***

We live in a hell where our very experience is being destroyed.

Ecopsychology was supposed to lead us out of this hell. It was going to do this by bringing together ecology and psychology to attack the illusion that we are fundamentally isolated from each other, the natural world, and ourselves. Theodore Roszak cites a 1990 conference held at the Harvard-based Center for Psychology and Social Change entitled “Psychology as if the Whole Earth Mattered” as one of the seminal events in the new ecopsychology movement. The ecopsychologists gathered there summed up one of ecopsychology’s defining goals: “if the self is expanded to include the natural world, behavior leading to destruction of this world will be experienced as self-destruction.”

A few years later, in 1995, the term “ecopsychology” entered the popular lexicon with the publication of a collection of writing by psychologists, deep ecologists, and environmental activists titled, “Ecopsychology: Restoring the Earth, Healing the Mind.” In what would become a foundational text in ecopsychology, Lester R. Brown, author and founder of the Worldwatch Institute and the Earth Policy Institute, provided an introductory piece, “Ecopsychology and the Environmental Revolution: An Environmental Foreword.”

Brown’s excitement was so high, he predicted “a coming environmental revolution” and wrote, “Ecopsychologists…believe it is time for the environmental movement to file… a ‘psychological impact statement’. In practical political terms that means asking: are we being effective? Most obviously, we need to ask that question with respect to our impact on the public, whose hearts and minds we want to win over. The stakes are high and time is short.”

If we use the 1990 conference as a beginning, ecopsychology has had 27 years to teach “Psychology as if the Whole Earth Mattered.” It has had 27 years to answer Brown’s question, “are we being effective?” It has had 27 years to win over the hearts and minds of the public. And, the stakes are only higher, time is only shorter.

Ecopsychology has failed. Ecologically, the diversity of life around the world is worse off with the rate of species extinction only intensifying in recent years. Psychologically, the rate of mental illness is even worse than in the 90s. And, as far as the “hearts and minds of the public”? Well, close to 63 million Americans just elected a climate change denier to the most powerful political position in the world.

Ecopsychology’s failure stems from an unwillingness to carry the material implications of the very insights ecopsychologists have made to these implications’ logical conclusion. These insights can be distilled into a few, potent premises.

***

I. The human mind originates in its experiences of its environment. In other words, the human mind is experiences of environment.

What do I mean by “environment”? For my purposes, the environment is the sum of all relationships, conscious and unconscious, physical, emotional, and spiritual, creating our lives.

Some of these relationships are as obvious as the sun’s heat, the moon’s pull, and the stars’ mysteries. Some of these relationships need no explanation: the nearness of your lover’s body, the taste of ripe blackberries, the sound of an elk bugle over the next ridgeline at dusk. Some of these relationships are as widely-studied as our dependence on our mothers’ bodies in the earliest stages of our development, as the dominance abusers gain over the abused, and as the influence modern advertising has on our desires. Some of these relationships – like the ones lost with the disappearance of hundreds of species daily, like the disintegration of connections with our ancestors, like the inability to make any sense of our dreams – have been ignored by the dominant culture for far too long.

One of the defining characteristics of ecopsychology, is a rejection of Descartes’ “I think, therefore, I am.” Ecology, recognizing that life is sustained by countless connections between living beings, replaces Descartes’ statement with “We relate, therefore, we are.” James Hillman articulates this rejection as a demonstration of the “the arbitrariness of the cut between ‘me’ and ‘not me’” that has dominated civilized thought for the past 4 centuries.

Out of this rejection comes the necessity for what Anita Burrows calls an “expanded view of self.” Drawing on her clinical experience with children, in her essay “The Ecopsychology of Child Development” Burrows argues, “If we see the child inextricably connected not only to her family, but to all living things and to the earth itself, then our conception of her as an individual, and of the family and social systems in which she finds herself, must expand.”

It is here that we first encounter implications that ecopsychology has proven unwilling to respond to. What do we find when we expand our vision of self to include “all living things and to the earth itself”? We find all living things under attack and the earth threatened with total collapse.

***

II. Human behavior originates in the human mind. So, human behavior originates in experiences of environment.

The origination of human behavior in the mind is neither new nor controversial. The origination of human behavior in experiences of environment is also largely accepted in mainstream psychology as long as that environment is limited to human social interaction.

Radical psychologist R.D. Laing, whose work brilliantly describes the alienation infecting Western humanity, succinctly explains the situation in his work The Politics of Experience, “Our behavior is a function of our experience. We act according to the way we see things.” Laing illustrates the importance of human relationships in our conception of self, “Men can and do destroy the humanity of other men, and the condition of this possibility is that we are interdependent. We are not self-contained monads producing no effects on each other except our reflections. We are both acted upon, changed for good or ill, by other men; and are agents who act upon others to affect them in different ways.”

Laing, for all his wisdom, examines only a small part of the environment producing the human mind. We can correct his vision and come to a deeper understanding of the human psyche if we accept the definition of “environment” I created above. Expanding Laing’s conception of self, we can re-write his analysis as: Humans can and do destroy the relationships sustaining life, and the condition of this possibility is that we are interdependent on countless connections. The natural world, which includes us, is both acted upon, changed for good or ill, by the totality of these connections. Our environment, whether it is a healthy natural community or an artificial human one, acts upon others to affect them in different ways.

***

III. Changes in experiences of environment lead to changes in human behavior. Healthy experiences of environment produce healthy behavior. Unhealthy experiences of environment produce unhealthy behavior.

This premise is Paul Shepard’s thesis in Nature and Madness. Beginning with the question, “Why does society persist in destroying its habitat?”, Shepard blames the physical destruction wrought by civilization and the way this destruction influences human ontogeny. A primary strength of Shepard’s analysis is the way he removes human destructiveness from abstractions like greed or evil and places them in concrete processes like biological development. In doing so, he robs those who blame human nature for the destruction of the planet of their excuse for inaction. He also pulls the rug from under ardent liberals who claim we need transformations of human hearts and that the best way to achieve these transformations is through therapy, education, and one-heart-at-a-time crusades.

Shepard blames the knowledge and human organization developed by civilization claiming it “wrenched the ancient social machinery that limited human births” and that “it fostered a new sense of human mastery and the extirpation of non-human life.” This resulted in not just psychopathic individuals, but in psychopathic cultures. Psychopathic cultures produce psychopathic individuals who, in Shepard’s words, heedlessly occupy “all earth habitats,” who physically and chemically “abuse the soil, air, and water,” who cause “the extinction and displacement of wild plants and animals,” and who practice “overcutting and overgrazing of forest and grasslands.”

Healthy human behavior, for Shepard, will only be achieved, then, by a return to the global existence of human hunter-gatherer societies. In doing so, we will return to a way of life in “which our ontogeny has been fitted by natural selection, fostering cooperation, leadership, a calendar of mental growth, and the study of a mysterious and beautiful world where the clues to the meaning of life were embodied in natural things.”

***

IV. Human behavior is destroying the environment. Destroying the environment produces unhealthy experiences of the environment which, in turn, produce unhealthy human behavior.

I am writing this looking out the glass windows of a coffee shop separating me from the reality of a -8 degrees Fahrenheit temperature in Park City, Utah. I can see the digital numbers on the coffee shop’s thermostat: 73 degrees.

I consider what lets me sit here, in comfort, while ten feet away, on the other side of the window, the air would cause the skin on my knuckles to crack and bleed. The energy required to keep this room warm is produced by burning a combination of natural gas sucked from beneath the earth’s surface where it played an integral role in forming the earth’s skin and coal formed by the decomposing remains of ancient forests ripped from wounds in the land. The combustion of the natural gas and coal produces great heat, but it also produces poisonous fumes that trap the earth’s heat in and melt polar ice caps, disturb rain patterns, contribute to species extinction, and threaten life with total collapse.

The glass, wood, aluminum, and steel that forms the wall between reality and me, and holds the warmth in, also allows me to focus my attention on the artificiality of my computer screen. For most of the morning, I am unaware of the gold flickering with the communion of the winter sun on frozen pine branches. I do not see the crystal purity of the cold blue sky. I cannot rejoice in the magic moment water freezes in mid-air to sparkle in a twisting sheen with the breeze.

I am also ignorant in the warning pain caused by cold. Without the sacrifice of the gas and coal, without the theft of the wood and minerals needed for the glass, maybe Winter’s voice would be too stern to withstand. Maybe, the cold is a command to humans to forsake the heights where the region’s pure waters collect. Maybe, the chill is telling us we are too clumsy, too awkward not to foul the waters that will support all of life here through the spring, summer, and fall.

In short, the destruction that produces my comfort allows my narcissism and encourages my apathy, while I continue to contribute to the destruction.

***

V. The cycle of violence perpetuates itself over generations and intensifies as unhealthy experiences of environment become the norm for most humans.

Freud asked, “If the development of civilization has such a far-reaching similarity to the development of the individual and if it employs the same methods, may we not be justified in reaching the diagnosis that, under the influence of cultural urges, some civilizations – or some epochs of civilization – possibly the whole of mankind – have become neurotic?”

It is not the “whole of mankind” that has become neurotic because there exist, and always have existed, original peoples who live in balance with their land bases. But, civilization itself, is insane. Derrick Jensen defines civilization as “a culture—that is, a complex of stories, institutions, and artifacts— that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities, with cities being defined—so as to distinguish them from camps, villages, and so on—as people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life.”

Civilization is insane because the civilized strip their land bases of the physical possibility of life. As civilization spreads, it leaves an ever-widening circle of destruction. The human minds that develop in this circle of destruction, have had their experience destroyed, and carry their destruction with them to destroy more lands. Each successive generation exists on lands more impoverished than the preceding generations experienced. The environmental catastrophe confronting us is the result of this insane cycle.

***

VI. The environment is finite. Eventually, humans will destroy the possibility of experiences of environment.

The relationships creating our lives can be diminished. Loved ones die, rivers run dry, mountaintops are removed, and species vanish forever. While this process intensifies, the first thing that happens is the diversity of our relationships is destroyed. To borrow Richard Louv’s phrase, we begin to suffer from “nature-deficit disorder.” As humans proliferate and “heedlessly occupy all earth habitats,” most human relationships become relationships with other humans.

R.D. Laing wrote, “If our experience is destroyed, our behavior will be destructive. If our experience is destroyed, we have lost our own selves.” If we expand Laing’s definition of “experience” to include non-human relationships, then we begin to see that not only is our experience destroyed, but the very possibility of experience is threatened.

The material world makes experience possible. Quite simply, without flesh to compose our bodies and brains, without water to carry nutrients to our bodies and brains, without minerals to facilitate electrical impulses, we cannot experience. As we destroy more topsoil, irreversibly alter the climate, and poison the world’s water supplies, we come ever closer to the moment flesh cannot grow, water is transformed from life-giver to death-bringer, and minerals are all trapped in steel beams rusting where they collapsed under civilization’s gluttonous weight.

***

VII. We must change human behavior. To change human behavior we must change human experiences of environment.

Medicine tells us that prevention is better than cure. And, eradication of illness is the ultimate prevention. Ecopsychology provides the map for the eradication of the psychopathology currently affecting civilized culture. If we want to prevent this psychopathology from infecting and destroying future generations of human and non-human life, we need to fundamentally alter the sick, disappearing, human-centric environments human minds are currently formed in. We must physically dismantle civilization to give the natural world a chance to heal and truly sustainable human cultures to thrive across the planet once more.

I’ve written several essays, now, making this same point and I’ve received a lot of feedback. Few people disagree with me, but I’ve been very disheartened to learn that many of my readers take my call to dismantle civilization as essentially an internal process. I’ve had writers tell me we need to “re-wild our minds” (as if that is possible without re-wilding the environments producing our minds), we need to grieve planetary and species’ destruction (and while we are grieving more of the planet is destroyed and more species lost which will, I assume, also need to be grieved creating a never-ending cycle of grief), and I’ve even been invited to live in a commune, off-the-grid in South America.

But, civilization is not a mental event. Civilization is a global, physical process that is destroying the planet. While it is producing climate change, ocean acidification, massive deforestation and desertification, there is nowhere to escape.

Unfortunately, too many students of ecopsychology who recognize this, instead of facing the need to physically dismantle the systems causing this collapse, too often retreat to the position that only personal therapy is possible and that the planet can only be saved by curing one mind at a time.

How can James Hillman who has provided so much insight, for example, write: “Psychology, so dedicated to awakening human consciousness, needs to wake itself up to one of the most ancient human truths: we cannot be studied or cured apart from the planet.” And, then, literally in the very next sentence write, “I write this appeal not so much to ‘save the planet’ or to enjoin my fellow therapists to retrain as environmentalists…My concern is also most specifically for psychotherapy…”?

How can Terrance O’Connor, practicing psychologist, narrate a story in which he answers the question “Why should we want mature relationships?” at a conference for divorced people with an outburst that included these statements: “The status quo is that the planet is dying!…healthy relationships are not an esoteric goal. It is a matter of our very survival and the survival of most of life upon this earth” and, then conclude his essay with “What is the responsibility of a therapist on a dying planet? Physician, heal thyself”?

The answer is found in the strength of the very ideology ecopsychology seeks to undermine. Planetary destruction is reduced to an ailment in individual human minds. While ecopsychology wisely recognizes that the human mind is formed by material relationships and that physical threats to these material relationships are physical threats to the human mind, when ecopsychologists concern themselves primarily with psychotherapy they contribute very little to the effort to prevent psychopathology. Ecological psychotherapy, as a practice to heal mentally ill individuals, is merely a band-aid over a gunshot wound.

The natural world does not need more ecotherapists, it needs ecomilitants. It needs strategic, organized resistance to civilization. I say this as someone whose life has been saved by ecotherapy. My life and the lives of those lucky few privileged enough to gain access to ecotherapy are nothing compared to annihilation of life on Earth. If we do not concentrate all our efforts at physically toppling the systems destroying the planet, no amount of therapy is going to save us.

I recall the starlight on Thomas’ peacefully sleeping face. I don’t want my nephew to experience the illnesses causing someone to seek the services of a therapist – ecological or otherwise. I want him to live in a world where the physical richness of his experience guarantees his healthy psychological development. I want him to live in a world that isn’t being destroyed.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 14, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Lierre Keith, author of Deep Green Resistance, has very clear views on

using nonviolent direct action. These views have been strongly influenced by Gene Sharp’s work. She states that the first question activists must answer is whether the political system they seek to change needs to be adjusted inside a basically sound institutional framework, or whether it requires more fundamental change. If the political system requires fundamental change, such change cannot be achieved by compromise or persuasion; it necessitates some kind of struggle that inherently involves conflict. Those who believe such institutions to be sound will “keep banging their head[s] against these institutions but the institutions will not yield to their fundamental principles.”

Keith points out that neither engagement in a struggle nor the use of force necessitates violence. At this stage the question of whether to use force or nonviolent tactics is premature; decisions about tactics come later.

Keith is critical of the liberal notion of consent, as she does not consider consent to be freely given. Consent is extracted from the ruled either ideologically or by terror and force. Therefore, the whole function of power is to extract consent. In Keith’s view, consent is actually a euphemism for submission. She explains how most of us don’t want to be forced to consent or submit, we want to be fully informed people who have actual choices to control the material conditions of our lives. We do not want to be given choices within such limited conditions; we want to actually control the conditions, so that our choices are choices in a meaningful sense. Keith states that, as a group, we can choose to remove our consent from the systems of power or not. If it is agreed that we wish to remove our consent, the question becomes: how best to do that? How best to get people to understand that they can remove their consent, and then, how to organise that withdrawal so the systems crumble?

Keith describes how nonviolent direct action impinges on the state’s power more directly than using force, because their power comes from the population. For Keith this is the important insight into why this technique works. When the population takes back their political, economic, and social power from the state then “the state is left with nothing.” Withdrawing power does not work if just done emotionally, and that this is where many on the left have gone wrong.

Another important point Keith makes is that nonviolent resistance to power makes visible the repression and structural violence of the system. Therefore, for a nonviolent campaign to work, those involved must maintain nonviolent discipline. Keith explains that such commitment is crucial to the success of this strategy because it reveals the violent overreaction of those in power. If the movement reacts with force, it will look like a riot to those observing (or those sitting on the sidelines trying to work out which side to join), and it will be difficult to distinguish between the violence of the state and the self-defense of the activists. Such a situation demonstrates how a diversity of tactics can be problematic – it can cause the movement to be viewed negatively and therefore make it less effective. Diversity of tactics does have a part to play in our struggle, but timing is important. I will discuss this topic more in a future post.

Keith is clear that verbally appealing to or begging the powerful for some kind of conciliation is not nonviolent direct action; it is a verbal appeal or a conciliatory effort. She states that these actions do not actually confront power but are merely a rational or emotional appeal. Nonviolent direct action doesn’t work because it is morally or spiritually superior, it works because it:

- exposes the violence of the state and demystifies power

- breaks through the psychology of the oppressed

- ultimately removes the support on which the powerful depend

Keith concludes that nonviolent direct action can work, but when determining our tactics we must always ask these key questions: is it going to work for the struggle we are in? Do we have enough people and time? It takes a lot of people and time to learn from the mistakes of initially using nonviolent direct action to get to a point when a movement can use it effectively. [1]

In Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, Ackerman and Kruegler argue that having a strategy and applying it properly are the most important factors determining the outcome of a nonviolent conflict.

They define strategy in this overarching sense as “a process by which one analyses a given conflict and determines how to gain objectives at minimum expense and risk.” [2] They also explain that “strategic performance is likely to be a significant, possibly the dominant, factor in the outcome of nonviolent struggle.” [3]

Ackerman and Kruegler also state the need to distinguish between policy, strategy, and tactics when addressing a conflict. Within this framework, “policy” consists of the objectives that define an acceptable outcome, and will therefore determine when the activists stop fighting. Strategy, in this more focused sense, is the plan for achieving the objectives, which may need to adapt to the group circumstances. Tactical decisions are related to how to initiate or respond to interactions with the opponent. [4] Ackerman and Kruegler identify twelve principles of strategic nonviolent conflict. [5]

Twelve Principles of Strategic Nonviolent Conflict

Principles of Development

1. Formulate functional objectives.

2. Develop organizational strength.

3. Secure access to critical material resources.

4. Cultivate external assistance.

5. Expand the repertoire of sanctions.

Principles of Engagement

6. Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control.

7. Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons.

8. Alienate opponents from expected bases of support.

9. Maintain nonviolent discipline.

Principles of Conception

10. Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic

decision making.

11. Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of the protagonists.

12. Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives.

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2gRtXp3qp8

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993, page 6

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 2

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 7

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 21 and read online

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org