by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 26, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

By Zoe Blunt, Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network

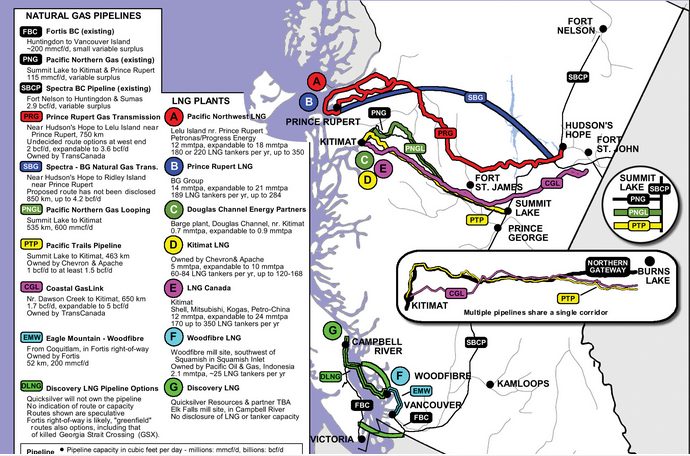

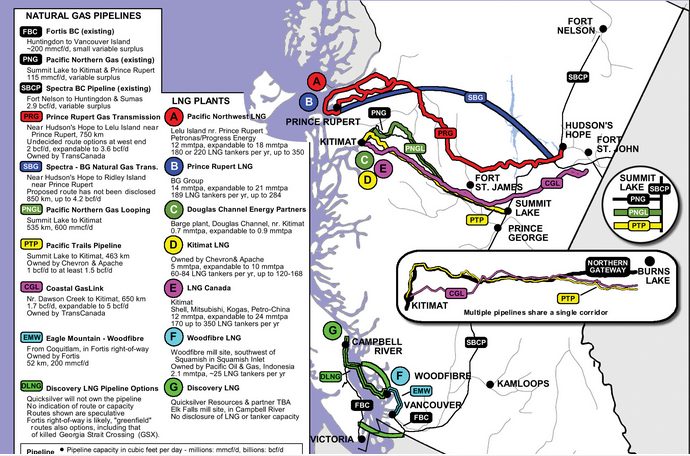

In every part of the province, industry is laying waste to huge areas of wilderness – unceded indigenous land – for mining, fracking, oil, and hydroelectric projects. This frenzy of extraction is funneling down to the port cities of the Pacific and west to China.

Prime Minister Harper has stripped away legal options to stop this pillaging by signing a new resource trade agreement with China that trumps Canadian and local laws and indigenous rights. Not even a new government has the power to change this agreement for 31 years.

For mainstream environmental groups (and my lawyers, who were in the middle of a Supreme Court challenge to the trade agreement when Harper pre-empted them), it is a total rout. We are used to losing, but not like this.

The only light on the horizon is the rise of direct resistance. BC’s long history of large-scale grassroots action (and effective covert sabotage) is the foundation of this radical resurgence.

This time it’s different. This time we can write off the Big Greens. Tzeporah Berman, once the face of the Clayoquot Sound civil disobedience protests and now head of the Tar Sands Solutions Project, is publicly proposing that enviros capitulate in the hopes of a slightly greener pipeline apocalypse.

As usual, Berman and her kind are far behind the people they pretend to lead. Public opinion is hardening against pipelines and resource extraction.

But the question hangs over us like smoke from an approaching wildfire. How to stop it? The courts are hogtied. The law has no power. The people have no agency. This government simply brushes them aside and carries on. We get it. We’ve had our faces rubbed in it.

This is activist failure. The phase of the movement when most of the public is already on side, when we have filed all the lawsuits, taken to the streets in every city, overflowed every public hearing, and uttered every threat we can muster – and the end result is they are bulldozing this province from the tarsands straight to the coast.

This is the moment when we can expect activists, especially mainstream enviros, to become demoralized and quit or capitulate. Or delude themselves. Green groups are casting about for a strategy that will allow their donors to maintain false hope in a democratic solution. Some are still trying to raise money for legal challenges that can simply be overruled by the treaty with China.

But small cadres are preparing the second phase of the resistance. Indigenous groups are reclaiming territory and blocking development at remote river crossings, on strategic access roads, and in crucial mountain passes. Urban cells are locking down to gates, vandalizing corporate offices, and organizing street takeovers.

It’s a good start. But now we have to look at how to be effective against powerful adversaries with the full weight of the law and the police on their side. How will we protect the land and each other, when push comes to shove?

The new rules don’t change our strategy to bring down the enemy: kick them in the bottom line. The resource sector will wind tighter as competition to feed China intensifies. Profits are slim enough to start with – made up in volume – and investors are jittery already.

We urge our allies to heed the lessons of history. We don’t win by giving up. Tenacity, flexibility, and diversity of tactics turn back the invaders.

Celebrate the warriors. Raise that banner now, and we’ll find out soon enough who’s with us, and who’s looking to appease our new dictators.

by DGR News Service | Aug 5, 2014 | Education, Indigenous Autonomy, Male Violence

By No More Silence

As Indigenous peoples, working for justice for #MMIW is a process that starts within our own communities. The launch of this website is one example of the resurgence of community documentation as justice.

In April of 2013, No More Silence, Families of Sisters in Spirit and the Native Youth Sexual Health Network began what has become a long term vision for a community-led database documenting the violent deaths and disappearances of Indigenous women. It is our collective hope that the lives of Indigenous Two Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTTQQIA) will also be recognized as gender based violence also impacts these communities and is often invisibilized.

The website is available for viewing at: www.ItStartsWithUs-MMIW.com

FSIS, community partner on this initiative indicated that they “support a grassroots led community database because Indigenous people are first and foremost the experts in gathering data and information about missing and murdered Indigenous women”. The launch of this website is an outcome from many community conversations with impacted families and individuals affected by colonial gender based violence.

1 year later and still no justice…The purpose of the database is to our honour women and provide family members with a way to document their loved ones passing. As the one year anniversary of Bella Laboucan-Mclean’s death approaches the family has provided the first of many tribute pieces on the website, available to read at: www.ItStartsWithUs-MMIW.com/bella

According to Melina Laboucan-Massimo, “Our family still does not have answers from the Toronto Police about Bella’s death which is still listed as suspicious. We appeal to anyone with information to come forward with answers. We urge the Toronto Police to investigate her death as if Bella were part of their own family and not just another police statistic. This new website and database gives families like ours the ability to not only document the lives of our loved ones but also commemorate and celebrate their lives and achievements.”

As the search for answers persists, we continue to urge the Toronto Police Service to maintain their focus on the details surrounding Bella’s death as the family and larger community follow this case closely. We are honoured to have Bella’s story be the first tribute that is shared on the website as a way of recognizing her life and spirit.

We also call attention to Sonya Cywink, murdered in London, ON who’s family and community are preparing a memorial on the 20th anniversary of her passing and are also holding out hope that one day they will uncover the mystery surrounding her murder.

Krysta Williams of the Native Youth Sexual Health Network and community partner, “We know there are many other stories, families and anniversaries, this is just the beginning. We continue to build capacity within our networks to respond and support.”

For more information and background on #ItStartsWithUs please read “Supporting the Resurgence of Community-Based Responses to Violence” at: http://www.nativeyouthsexualhealth.com/march142014.pdf

No More Silence Media Contact:

Audrey Huntley

Phone:647-981-2918 Email: audreyhuntley@gmail.com

Bella’s Family Media Contact:

Melina Laboucan-Massimo

Phone:780-504-5567 Email: miyowapan@gmail.com

Native Youth Sexual Health Network Media Contact:

Erin Konsmo, Media Arts Justice and Projects Coordinator

Email:ekonsmo@nativeyouthsexualhealth.com

From Warrior Publications: http://warriorpublications.wordpress.com/2014/07/16/database-website-for-missing-and-murdered-indigenous-women/

by DGR News Service | Aug 4, 2014 | Colonialism & Conquest, Lobbying

By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance San Diego

There’s a common joke I’ve heard many indigenous people tell. It goes like this: “What did indigenous peoples call this land before Europeans arrived? OURS.”

This joke – or truth – reflects many of the problems inhering to the Supreme Court of Canada’s recent ruling in Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44. From my radical view, the Tsilhqot’in decision leaves much to worry about. In this article, I examine the decision written by Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin to show why the decision is not as helpful it would seem and I anticipate how the government and corporations will bend the decision to their goals.

For me, the term “radical” denotes going to the roots of the problem. First Nations are suffering under the yoke of colonialism. Colonialism is the problem. To undermine colonialism, we must understand the processes making colonialism possible. One of the most powerful institutions perpetuating colonialism is the Canadian government and the Canadian court system as a branch of the Canadian government. It is my view that – for now – we must read the Tsilhqot’in decision not so much as a victory, but as another step down the long road of insidious colonialism.

First, there’s the general and underlying defeat that comes with the fact that colonialism has been so dominant in Canada that First Nations must submit to decisions made by Canadian courts. My second problem with the decision involves facing that there can be no true ownership of land when a dominated people must ask the courts of their conquerors for validation of their right to their own homelands. Placing the burden on First Nations to prove their land claims is another act of arbitrary power that works against cultural survival. Finally, I am deeply anxious about how clearly the Court spells out just what kind of governmental projects would be the type that the Court would sign off on. These projects include mining, forestry, agriculture, and the “general economic development of the interior of British Columbia.”

What Appealing to the Legal System Means

When celebrating what we view as a “good” decision by an imperial court it is easy to forget that the goal is to dismantle the power that gives the court its authority. We must not begin to view the so-called justice system as something like a benevolent paternal figure to appeal to when big-bad corporations come to destroy the land.

We must never forget that there will never be true justice in the courts of the oppressors because the courts of the oppressors are designed to protect the oppressors. Private property laws are the perfect example of this. What happens if you’re starving, walk into Walmart, take a loaf of bread, and are caught? You will be charged with transgressing property laws, dragged into court, and punished by the court for your transgression. Walmart’s right to a loaf of bread trumps your right to eat.

What does it mean, for example, that the Tsilhqot’in had to ask the courts to give them a right to land that they have lived on for thousands of years? Can a people ever truly own their land if they have to ask an occupying court to recognize their claims to land? The court protected the Tsilhqot’in after twenty-five years of deliberation, but what happens to the next aboriginal group that appeals to the courts and loses?

How is Aboriginal Title Established?

First, the Court lays out the process for establishing Aboriginal title. The burden falls on the Aboriginal group claiming title to prove its title. This means that a First Nation existing on its land for thousands of years must pay lawyers and subject its people to the stress of a legal proceeding – in courts established by settlers with access to First Nations land through centuries of genocide – to prove that the land is, in fact, theirs.

Aboriginal title is based on an Aboriginal group’s occupation of a certain tract of land prior to assertion of European sovereignty. A group claiming Aboriginal title must prove three characteristics about their occupation of a certain tract of land. First, they must prove their occupation is sufficient. Second, they must prove their occupation was continuous. Third, they must prove exclusive historic occupation. (¶ 50)

Proving Sufficient Occupation

To prove sufficiency of occupation, an Aboriginal group must demonstrate that they occupied the land in question from both an Aboriginal perspective and a common law perspective.

The Aboriginal perspective “focuses on law, practices, customs, and traditions of the group” claiming title. In considering this perspective for the purpose of Aboriginal title, the court “must take into account the group’s size, manner of life, material resources, and technological abilities, and the character of the lands claimed.” (¶ 35)

The common law perspective comes from the European tradition of property law and requires Aboriginal groups to prove they possessed and controlled the lands in question. As the Court explains, “At common law, possession extends beyond sites that are physically occupied, like a house, to surrounding lands that are used and over which effective control is exercised.” (¶ 36)

Simply put, proving sufficiency of occupation requires that the group claiming Aboriginal title were involved with the land in question more deeply than just using it in passing.

Proving Continuity of Occupation

Proving a continuity of occupation “simply means that for evidence of present occupation to establish an inference of pre-sovereignty occupation, the present occupation must be rooted in pre-sovereignty times.” So, the group claiming Aboriginal title must provide evidence that they were on the land in question in pre-sovereignty times. (¶ 46)

Exclusivity of Occupation

The last of the three general requirements for establishing Aboriginal title burdens a group with proving they have had the intention and capacity to retain exclusive control over the lands in question. As with sufficiency of occupation, the exclusivity element requires that the court view the evidence from both the Aboriginal and common law perspectives. According to the Court, “Exclusivity can be established by proof that others were excluded from the land, or by proof that others were only allowed access to the land with the permission of the claimant group. The fact that permission was requested and granted or refused, or that treaties were made with other groups, may show intention and capacity to control the land.” (¶ 48)

What Rights Does Aboriginal Title Confer?

This is one of the most important issues addressed by the Court in Tsilhqot’in – for what it says and what it does not say. The important thing to know here is that Aboriginal title does not provide Aboriginal groups with complete control of their own land. It may be common sense to assume that once an Aboriginal group gains Aboriginal title to their ancestral lands they are free to use their land how they see fit free of government interference. This simply is not true. And the Court is very clear to explain that this is not true.

According to the Court, “Aboriginal title confers ownership rights similar to those associated with fee simple, including: the right to decide how the land will be used; the right of enjoyment and occupancy of the land; the right to possess the land; the right to the economic benefits of the land; and the right to pro-actively use and manage the land.” (¶73)

In the English common law, “fee simple” refers to the highest form of ownership of land. Traditional rights associated with “fee simple” are the ones mentioned in the quote above. As the Court explains, “Analogies to other forms of property ownership – for example, fee simple – may help us understand aspects of Aboriginal title. But they cannot dictate what it is and what it is not.” (¶72) The Court quotes Delgamuukw, “Aboriginal title is not equated with fee simple ownership; nor can it be described with reference to traditional property law concepts.”(¶72)

It is important to note, of course, that Aboriginal title does not actually give Aboriginal groups full ownership of their own land. Aboriginal title has some key restrictions.

The Court explains: Aboriginal title “is collective title held not only for the present generation but for all succeeding generations. This means it cannot be alienated except to the Crown or encumbered in ways that would prevent future generations of the group from using and enjoying it. Nor can the land be developed or misused in a way that would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land. Some changes – even permanent changes – to the land may be possible. Whether a particular use is irreconcilable with the ability of succeeding generations from the land will be a matter to be determined when the issue arises.” (¶74)

So, once Aboriginal title is established, Aboriginal groups can only sell or give their land back to the Crown. On top of this, the Court creates open doors for future litigation with all the restrictions. Aboriginal groups will be subject to defending their decisions from accusations that they do not know how to manage their own lands for the benefit of future generations. Forcing Aboriginal groups to defend their actions in Canadian courts is a statement that the courts know how to manage Aboriginal lands better than Aboriginal peoples.

Finally, through Tsilhqot’in, Aboriginal title is subject to being over-ridden by governments and other groups on the basis of the broader public good – which often spells disaster for First Nations and natural communities.

Infringing on Aboriginal Title

Government and other groups may infringe on Aboriginal title – or use Aboriginal lands against the wishes of aboriginal peoples – on the basis of the broader public good if it “shows (1) that it discharged its duty to consult and accommodate, (2) that its actions were backed by a compelling and substantial objective, and (3) that the governmental action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary obligation to the group.” (¶ 77)

The Duty to Consult

The Court predicates the duty to consult on what it calls the “honour of the Crown” and says that the “reason d’etre” of the duty to consult is the “process of reconciling Aboriginal interests with the broader interests of society as a whole.” (¶77 and 82)

It sets up a sliding scale for adjudicating just how hard the government or other groups must try to consult Aboriginal groups. The duty to consult is strongest where Aboriginal title is proven and weaker where the title is unproven. The Court quotes the Haida decision, “In general, the level of consultation and accommodation required is proportionate to the strength of the claim and the seriousness of the adverse impact the contemplated governmental action would have on the claimed right. The required level of consultation and accommodation is greatest where title has been established.” (¶ 79)

Nowhere does the Court say that a government or other group must literally accommodate the wishes of Aboriginal groups. Yes, the government has a duty to consult. But, the government is not charged with an absolute duty to respect the wishes of an Aboriginal group with title to land the government wants. No never actually means no when the government is concerned.

Compelling and Substantial Objectives

The Court is very careful to articulate that there are compelling and substantial objectives that would justify infringement on Aboriginal title. Just like we saw with the duty to consult, the Court will view what objectives will justify infringement through a desire to reconcile Aboriginal interests with the broader interests of society as a whole.

On its surface, this sounds great, but then the Court quotes the Delgamuukw decision to illustrate just exactly what kinds of activities might qualify as a compelling and substantial objectives (when reading this list, keep in mind the kinds of projects we are fighting against right now): “The development of agriculture, forestry, mining, and hydroelectric power, the general economic development of the interior of British Columbia, protection of the environment or endangered species, the building infrastructure and the settlement of foreign populations to support those aims, are the kinds of objectives that are consistent with this purpose and, in principle, can justify the infringement of aboriginal title.” (¶ 83)

We have to recognize how dangerous this language is. Enbridge has long anticipated the language. You could pick any number of prominent quotes from Enbridge’s Northern Gateway website www.gatewayfacts.ca to see how Enbridge is already spinning rhetoric to match the Court’s Tsilhqot’in ruling.

Take this one, for example, under the heading, “A boost for our economy,” “Northern Gateway will bring significant and long-lasting fiscal and economic benefits. Economically, the project represents more than $300 billion in additional GDP over 30 years, to the benefit of Canadians from every province.”

Or this one under the heading “Building communities with well-paying jobs,” “The pipeline sector creates thousands of jobs across the country. In B.C. alone, Northern Gateway will help create 3,000 new construction jobs and 560 new long-term jobs. The $32 million per year earned in salaries will directly benefit the families and economies of these communities.”

This is exactly the type of governmental objective that the Court in Tsilhqot’in suggests is compelling and substantive enough to pass constitutional muster.

It is important to understand how easy it is to be misled by our desire for good news in the fight to defend the land and First Nations communities. While there are helpful aspects of the Tsilhqot’in ruling on Aboriginal title, the Court is a long way from giving First Nations total control over their own lands. It may be safer for land defenders to assume that nothing really has changed. Yes, Aboriginal title has been defined, but how meaningful is that title if governments and corporations can override title by pointing to the “general economic development of the interior of British Columbia”?

The Crown’s Fiduciary Duty

The final hurdle a government or other group must clear in infringing on Aboriginal title is proving that the proposed action is consistent with the Crown’s fiduciary duty to the Aboriginal group. This fiduciary duty supposedly requires the Crown to act solely in Aboriginal groups best interests. The problem, of course, is that it is the courts that decide what is in an Aboriginal groups best interest.

The Court explains that the Crown’s fiduciary duty impacts the infringement justification process in two ways. “First, the Crown’s fiduciary duty means that the government must act in a way that respects the fact that Aboriginal title is a group interest that inheres in present and future generations…This means that incursions on Aboriginal title cannot be justified if they would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land.” (¶ 86)

The second way it impacts the infringement process is by imposing an obligation of proportionality into the justification process where the government’s proposed infringement must be rationally connected to the government’s stated goal, where the government’s proposed action must minimally impair Aboriginal title, and where the benefits the government expects to accrue from the proposed action are not outweighed by adverse effects on Aboriginal communities. (¶ 87)

Another glimpse at the Enbridge’s Northern Gateway website (http://www.gatewayfacts.ca/benefits/economic-benefits/) demonstrates how Enbridge anticipates the Court’s ruling. Under a heading titled “Aboriginal inclusion” the website reads, “First Nations and Metis communities were offered to become equity partners providing them a 10% stake in the project. With the $300 million in estimated employment and contracts, it adds up to $1 billion in total long-term benefits for Aboriginal communities.”

I do not think it is a stretch to expect that Canadian courts will rule that Aboriginal groups denying projects like the Northern Gateway are working contrary to their own best interests. But, this isn’t even really the point. The point is, for all the progressiveness we want the Tsilhqot’in decision to stand for, it still allows the courts to decide what the best interest of First Nations is and not First Nations themselves. The longer this system remains intact, the longer First Nations communities will be in danger.

“We don’t want any more salmon farm sites in our territory and will be taking a much closer look at this industry,” Joe James Rampanen.

“We don’t want any more salmon farm sites in our territory and will be taking a much closer look at this industry,” Joe James Rampanen.