Colonial frontlines in the city: urban Indigenous organizing

In so-called Canada, urban Indigenous organizers are re-energizing a decades-old struggle by redefining Indigenous sovereignty in the city streets.

By Natalie Knight originally published on roarmag.org

featured image by Sharon Kravitz

“I brought you all some water,” I said to the ragtag crew of six holding our “All Nations Unite With Wet’suwet’en” banner across the lane of semi-truck traffic heaving out of the Port of Vancouver. We had been standing, rotating positions, for five hours now.

A hundred feet away, 200 people formed a square around the intersection of Hastings Street and Clark Drive, blocking semis, buses, and drivers headed to the glass towers of downtown. At the center of the intersection, Elders from local nations sang and drummed. With a pivot of their feet, they honored the four directions: north, south, east, and west.

I walked back to the intersection and stood with the man from yesterday’s march. He had been making his way through the crowd, offering people sage for smudging, a common cleansing ceremony. He held out his hands.

“I have to go soon. I didn’t smudge you yet. I want to give you this.” His hands held the abalone shell, the burning medicine, and feathers. Then, he looked me steadily in the eye and said, “I see you. We see you.”

Tears blurred my vision. I brought the smudge bowl to the table under the tent and cleared away bags of chips and plastic containers of muffins. I smudged. The medicine drifted through the air, and Dennis, the man from Moricetown on the Wet’suwet’en nation, walked away, toward the east. I held the feathers until, exhausted and triumphant, we marched out of the intersection as the winter dusk fell in the late afternoon.

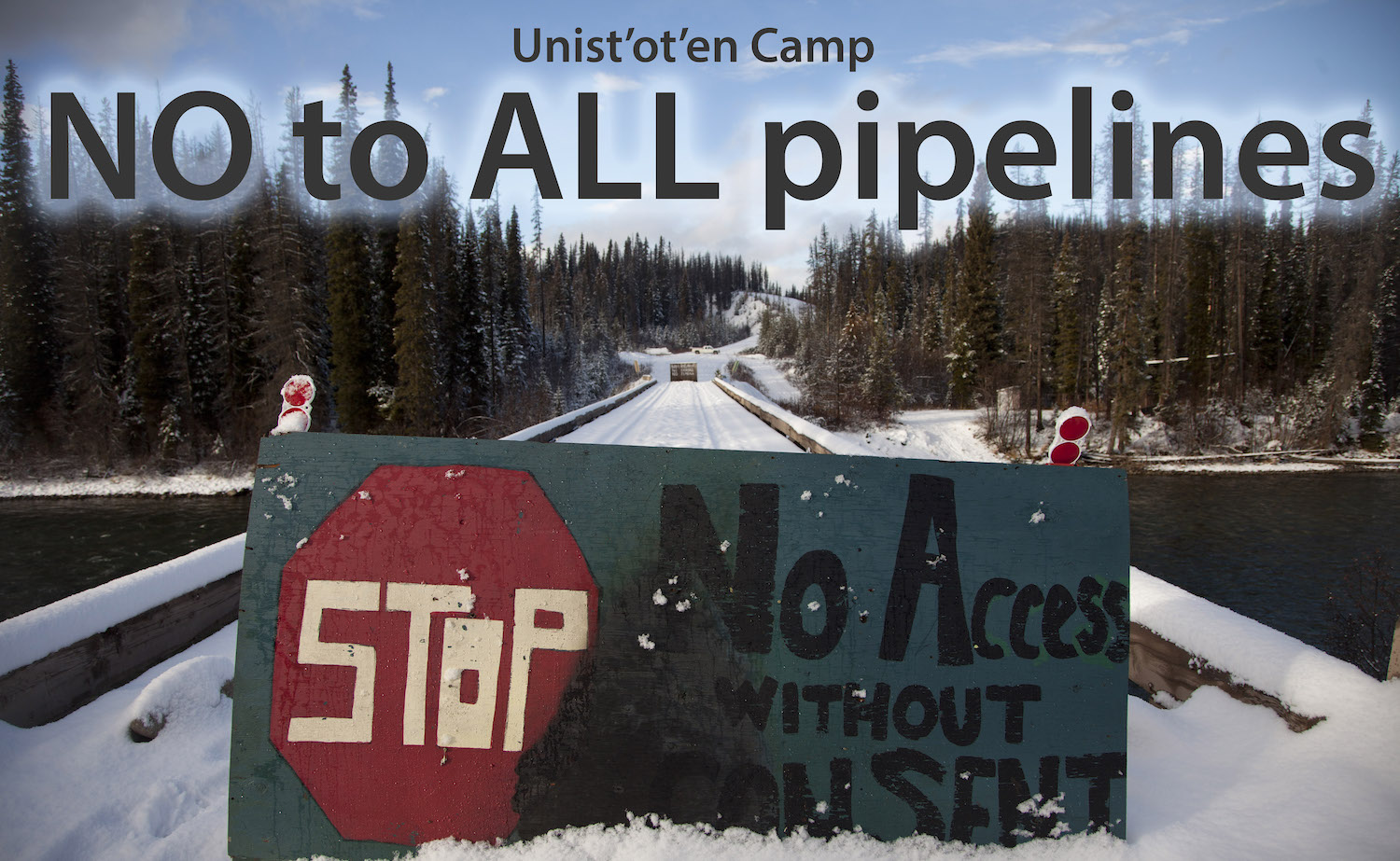

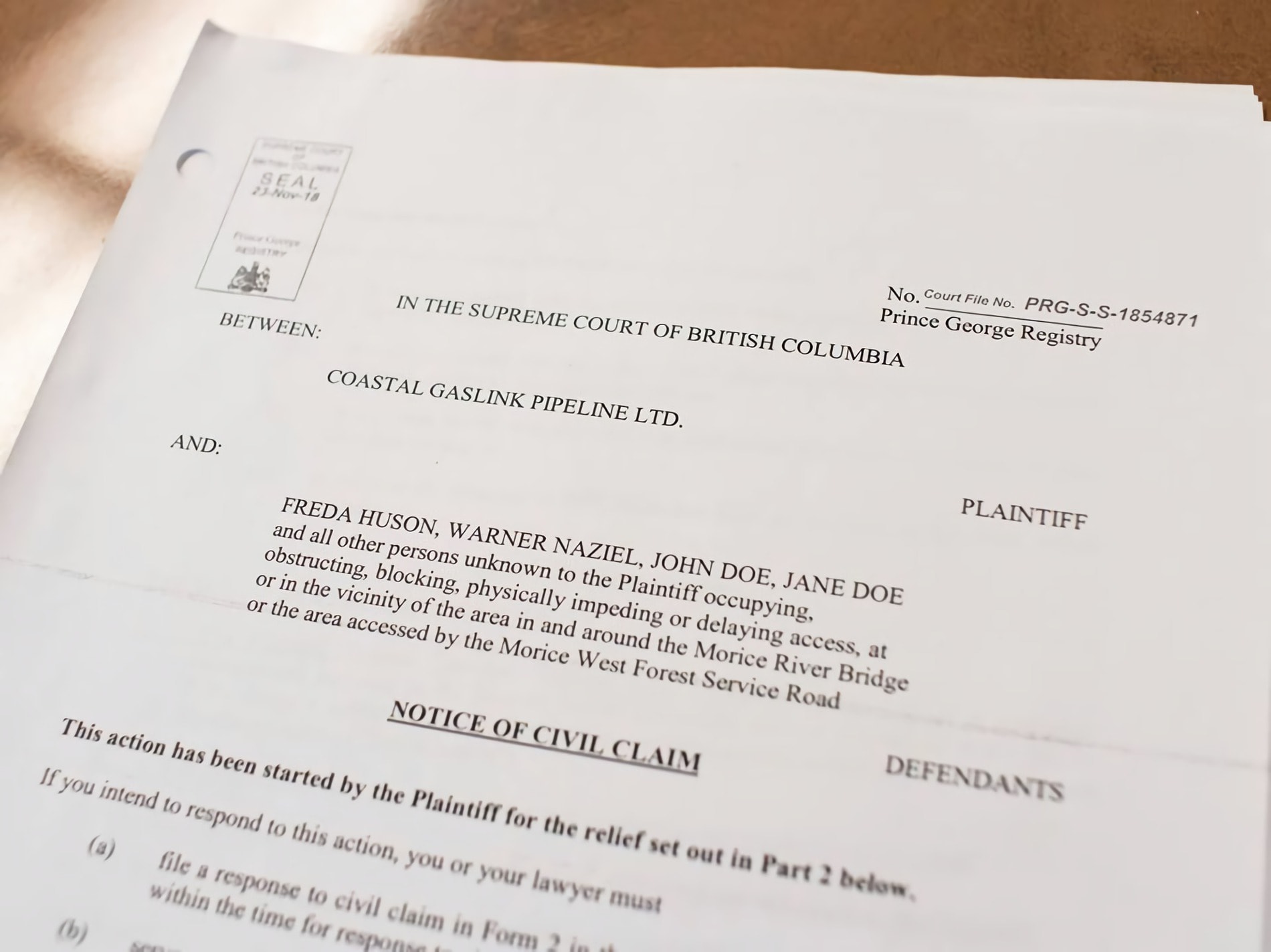

That day, January 9, 2019, urban Native organizers led a six-hour blockade of the Port of Vancouver. We were responding to attacks by the RCMP, Canada’s paramilitary police force, on Wet’suwet’en people who have reoccupied their territory since 2010. The RCMP have been authorized by the British Columbia Supreme Court to forcibly clear a path for the construction stage of Coastal GasLink’s fracked gas pipeline. We targeted the Port because it is one of the most valuable economic sites in Vancouver, with goods worth hundreds of thousands of dollars passing through each hour. We targeted the Port to show the colonial state that Indigenous people will not sit quietly by while our cousins and comrades are under attack.

Since December 10, 2018, we have organized five other solidarity actions in Vancouver. We have occupied Coastal GasLink’s corporate offices; organized three simultaneous sit-ins of New Democrat Party (NDP) politicians’ offices (the “progressive” Party in BC under whose direction the RCMP is acting); led a march through downtown that blocked two bridges; mobilized 1,500 people into the streets of Vancouver to hear inspiring speeches; and, most recently, blockaded a rail line that leads into and out of the Port.

These actions have been strong, righteous acts of solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en nation in northern British Columbia. As urban Native organizers, we stand by our cousins and comrades at Wet’suwet’en.

This moment of organizing is fierce, but within our own communities, we talk quietly about the absence of sustained urban Native organizing, outside of the “flashpoints” of solidarity actions that we often lead in the city for Indigenous land defenders on the remote frontlines. In settler-colonial Canada, these flashpoints inevitably come every few years, but our organizing does not sustain itself beyond our reactions to violations of Indigenous sovereignty on the land.

Many of us wonder: where is our movement?

Red Power Roots

There is an incredible history of urban Native organizing in Canada and the United States. One of the most famous was the Indigenous sovereigntist Red Power movement, which was most active and visible between the 1960s and the 1980s. Many groups organized during Red Power, but perhaps the most popularly known organization is the American Indian Movement.

Red Power was sparked when Indigenous fishing rights, secured through treaties, were threatened. In response, Indigenous activists in Washington State staged “fish-ins,” risking arrest to fish in their own waters. Then in 1969, the 19-month reoccupation of Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay gained massive mainstream media attention and pushed issues of Native sovereignty and rights into the public discourse. Red Power was a pan-Indian movement that focused on unity between diverse Indigenous nations in the face of the colonial states of the US and Canada.

There are many ways that the stories of Red Power are told. Many who lived through the era speak about the movement’s internalization of colonized gender roles, and how this affected the leadership of women and two-spirit people. And most storytellers agree that the politics within Red Power shifted from a pan-Indian sense of unity to revitalizing cultural and spiritual practices specific to individual nations. On the ground, this often meant leaving the city as a site of organizing and going back to reservation or rural Indigenous communities.

There are lots of explanations for this shift, but from my perspective, this change was a complicated result of internal shifts in consciousness within the Red Power movement and external forces, including the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) targeting of the American Indian Movement; discourses of multiculturalism, most obviously instated through Canada’s 1988 Multiculturalism Act; the colonial states’ responses to broader Civil Rights-era movements by shifting money into education, which threatened social movements by offering routes to entry into the middle class; and, in the US, affirmative action policies.

With this shift away from pan-Indian identity and unity, Indigenous peoples in Canada and the US often began to return to their communities on traditional territories or reserves (in Canada) and reservations (in the US). Indigenous people also began, in earnest, relearning and revitalizing their languages, cultural and spiritual practices, and traditional or hereditary governmental structures, which, for centuries, the colonial governments had attacked and criminalized. Indigenous reoccupations of traditional territories, like at Wet’suwet’en in northern British Columbia, are the fruits of the tail end of the Red Power movement.

Yet, some urban Native organizers feel the loss of the pan-Indian politic: urban Indigenous people without a home territory to return to cannot connect to land-based activism. At issue is what sovereignty means to Indigenous people in Canada and the US, and whether we can expand our notion of sovereignty in ways that build connections and alliances between diverse experiences and expressions of Indigeneity in the early 21st century.

At issue is how urban Natives can assert our sovereignty as people who have been deeply dispossessed of our traditional territories, on the one hand, and find the city to be a rightful place of land relationships, on the other.

Who urban Natives are

In Canada, more than half of all Indigenous people live in urban centers, and more than 70 percent of American Indians and Alaskan Natives live in cities in the US. Many Red Power activists in the US had been removed from reservations into major cities through the 1956 Relocation Act. Today, we find ourselves in the city for many reasons: surviving foster care or gendered violence, adoption, the search for jobs, legacies of residential schools and intergenerational trauma, fractured kinship networks. There are almost infinite reasons. In cities, we form strong urban Native communities. We make long-lasting and loving connections with diverse Indigenous people from many nations across so-called Canada. We make the city our home.

The realities of life for urban Natives often collide with settler expectations for Indigenous people; while many of us may be rooted in our cultures, many of us are not. While some of us may visit the reserve often, some of us don’t even know which reserve is ours. The gaps in our historical memories are not our individual faults; they are the effects of colonialism, which has attempted for hundreds of years to wreck our kinship systems, our non-capitalist economies, and our cultural knowledges.

Indigenous movements today emphasize returning to the land, leading many Indigenous sovereigntists to reoccupy territories, participate in ceremony, and relearn languages and cultural practices. Reoccupying land is perhaps the foremost expression of Indigenous sovereignty because Canada and the US are actively engaged in a never-ending war for land. Refusing to be confined to reserves or reservations, and refusing to be dispossessed of our territories, asserts our sovereignty in ways that defy settler laws and settler entitlement. These trajectories are enormously inspiring, and hold great potential for Indigenous nationhood.

But this era of Indigenous sovereignty expressed most radically through reoccupation of territories makes it complicated for urban Native people to participate. Many of us live in poverty and face questions of survival in our daily lives. Many of us have fled our communities due to violence; others have severed relationships with our communities due to the varied effects of colonialism. Many of us cannot “go home.”

Urban Natives in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en

In between these two tendencies, I have quietly fought to carve out space for urban Natives to make connections with our cousins and comrades at Wet’suwet’en, and elsewhere. In Vancouver, I have been organizing with an ad hoc coalitional group that includes both settlers and Indigenous people. We come from different organizations and different politics and backgrounds. Our greatest shared point of unity is the political principle of Indigenous sovereignty, and a belief, different as it may be given our social and historical positions, in our responsibility to respond to this moment of colonial attack on Indigenous sovereignty in the streets.

Our work responds to two challenges: one is to create a place in Indigenous sovereignty movements to ensure that land defense politics also see the city as land; the second is to find a place for Indigenous struggles within class-based urban grassroots movements, which tend to elide the very real forces of colonialism that also structure the city.

In addition to my involvement with Wet’suwet’en solidarity organizing, I have been a member for the past seven years in an anti-capitalist and anti-colonial organization, Alliance Against Displacement. Our community organizing work has tended to focus on low-income struggles, homeless tent cities, and renter’s struggles. More recently we have started a campaign led by trans women called Bread, Roses and Hormones and a campaign against the police in the suburb of Surrey, called Anti-Police Surrey.

From the first years of being involved with Alliance Against Displacement, the urban Indigenous people within the group have wanted to start an urban Indigenous campaign. We have yearned to do this, ached over it, spent many hours dedicated to theorizing what an urban Indigenous campaign would look like in the second decade of the 21st century. We met with homeless Indigenous people in tent cities. We held talking circles for self-identified Indigenous people in Vancouver. It was hard to find the spark that could sustain a movement, and that is ultimately what we hoped to build through a campaign.

In the past two months of organizing Wet’suwet’en solidarity actions and support in Vancouver, I have felt a shift. We urban Native people are in the streets blocking ports, rail lines, speaking freely about our right to our land, our sovereignty, our nationhood. We are drumming and singing unapologetically, leading marches of thousands of people, some of us dressed in our traditional regalia happily standing beside some of us dressed in jeans and Wu-Tang sweatshirts. We are meeting each other spontaneously in the streets, building connections, and sharing politics. We are connecting with political elders, like Ray Bobb, who was involved with the Native Alliance for Red Power in the 1960s and 70s in Vancouver. We are meeting youth, like the young Stó:lô woman Sii-am, who spoke in the whipping wind and pouring rain just after we shut down a major transportation route in downtown Vancouver one evening.

While the violence against Wet’suwet’en people, and Wet’suwet’en land, is yet another mournful example of colonialism in Canada, I also see great potential in this moment. Urban Native people are being catalyzed through the Wet’suwet’en assertion of sovereignty. We are rekindling our voices, hearing new voices, developing a more explicit politics of sovereignty that takes us into the streets.

The future of urban Indigenous organizing

The Wet’suwet’en confrontation with colonial power has mobilized many of us Indigenous people, Wet’suwet’en and others, rural or urban. Urban Native people are rising right now, leading solidarity actions in cities across Canada, increasingly taking our rightful place in Indigenous sovereignty struggles.

We are targeting sites of economic trade and exchange, like ports and railways, because we know that colonialism and capitalism are entwined forces that must be fought simultaneously. We are taking to the streets alongside anti-capitalist organizers who are deeply committed to anti-colonial struggle, and recognize the necessity of dual movements against capitalism and colonialism in so-called Canada.

We are defying the “ally” politics that have plagued Indigenous land defense solidarity work for at least 15 years now, politics that center white activists and their relationships with Indigenous land defenders while simultaneously viewing urban Natives as “less Indian” than our rural cousins and comrades.

We are building from the strengths of the Red Power era of organizing in the 1970s and 80s, and moving past its weaknesses.

We are inheriting the consciousness-raising staged through Idle No More, an Indigenous movement that spread from Canada to the US in 2013, and are pushing this movement further, making on-the-ground connections between culture, land, and sovereignty.

We are creating a new politics that honors the particularities of individual nations’ land relationships, cultures, and knowledges while also embracing urban Natives as people with political agency as well.

We are synthesizing the varied and diverse Indigenous sovereignty efforts into a movement that has the numbers, strategic alliances, and political vision needed to fight Canadian colonialism.

We are acting in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en frontline, and we are also saying: the colonial frontlines are everywhere.

DONATE to

DONATE to