by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 10, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image by Comunicación Sin Paredes.

by John McPhaul / Cultural Survival

On August 9, 2018, the UN International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, the Costa Rican National Front of Indigenous Peoples made up of members of the Cabecare, Bribri, Teribe, Ngöbe and Ngöbe Bugle Peoples gathered at the National Assembly and issued a declaration stating that the Costa Rican government answered their call to pass an Indigenous autonomy law with “violence, ethnocide, impunity, humiliation, contempt and discrimination against the Indigenous Peoples of Costa Rica.”

“On August 9, 2010, Indigenous delegates and representatives, sick and tired of waiting for a debate on the Autonomous Development of the Indigenous Peoples Law project, met in the Legislative Assembly in San José to demand a yes or no to that project,” stated the declaration. “Their answer was to remove us with violence, beatings and dragging from the Legislative Assembly, as criminals.”

Indigenous leaders said that they returned to their “peoples and territories to continue with the struggle for autonomy, recovering [their] lands and territories, spirituality, cultures and strengthening [their] own organizations.”

“Throughout these years of exercising our rights we have been shot, macheted, beaten, threatened with death, slandered, offended, imprisoned and denounced,” said the declaration, “and despite all we have denounced, impunity prevails in all cases.”

The State of Costa Rica, through its different administrations, has ignored the national and international laws that protect and safeguard the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The declaration comes as the controversy over the take-over of Indigenous lands in the southeastern region of Salitre continues to simmer.

Teribe and Bribri peoples in 2014 took their case to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and obtained an order obliging the government of Costa Rica to take precautionary measures to protect Indigenous Peoples against non-Indigenous settlers on Indigenous land. In July 2012, Sergio Rojas, a Bribri community leader, led Bribri and Teribe community members in an effort to reclaim land within the Salitre Indigenous reserve in the Talamanca Mountains in southwestern Costa Rica.

Though the 11,700 hectares of land had been guaranteed to Indigenous communities by a 1977 Indigenous Law. The failure of the government to compensate landowners or control the illegal sale of the land to “white” outsiders resulted in the displacement of Indigenous communities.

The government at the time said addressing Indigenous people’s complaints was complicated by the fact that various factions exit in Indigenous communities. While the territory belongs to the Bribri people, cases exist of Bribris married to outsiders or to the closely related Cabecar people, complicating ownership rights.

In the August 9 declaration, Indigenous leaders requested a meeting with President Carlos Alvarado to discuss and propose concerns and like the previous rulers, the President ignored requests, and on the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, the day Indigenous Peoples of Costa Rica were violently evicted from the Legislative Assembly will be commemorated.

“We reaffirm our struggle for our autonomy, land, and freedom. We maintain our slogan of total recovery of Indigenous territories, in the process of autonomous territorial affirmation, which includes land, territory, governance, culture and spirituality. We support the peoples who are recovering their territories and denounce any compensation that is intended to be made to the usurpers of our land.”

–John McPhaul is a Costa Rican-American freelance writer. During his many years in Costa Rica, the land of his birth, he wrote for the Miami Herald, Time Magazine and Costa Rica’s The Tico Times among other publications.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 29, 2017 | Building Alternatives

Featured image: Monique Quesada

by Jason Hickel / Local Futures

Earlier this summer, a paper published in the journal Nature captured headlines with a rather bleak forecast. Our chances of keeping global warming below the 2C danger threshold are very, very small: only about 5%. The reason, according to the paper’s authors, is that the cuts we’re making to greenhouse gas emissions are being cancelled out by economic growth.

In the coming decades, we’ll be able to reduce the carbon intensity of the global economy by about 1.9% per year, if we make heavy investments in clean energy and efficient technology. That’s a lot. But as long as the economy keeps growing by more than that, total emissions are still going to rise. Right now we’re ratcheting up global GDP by 3% per year, which means we’re headed for trouble.

If we want to have any hope of averting catastrophe, we’re going to have to do something about our addiction to growth. This is tricky, because GDP growth is the main policy objective of virtually every government on the planet. It lies at the heart of everything we’ve been told to believe about how the economy should work: that GDP growth is good, that it’s essential to progress, and that if we want to improve human wellbeing and eradicate poverty around the world, we need more of it. It’s a powerful narrative. But is it true?

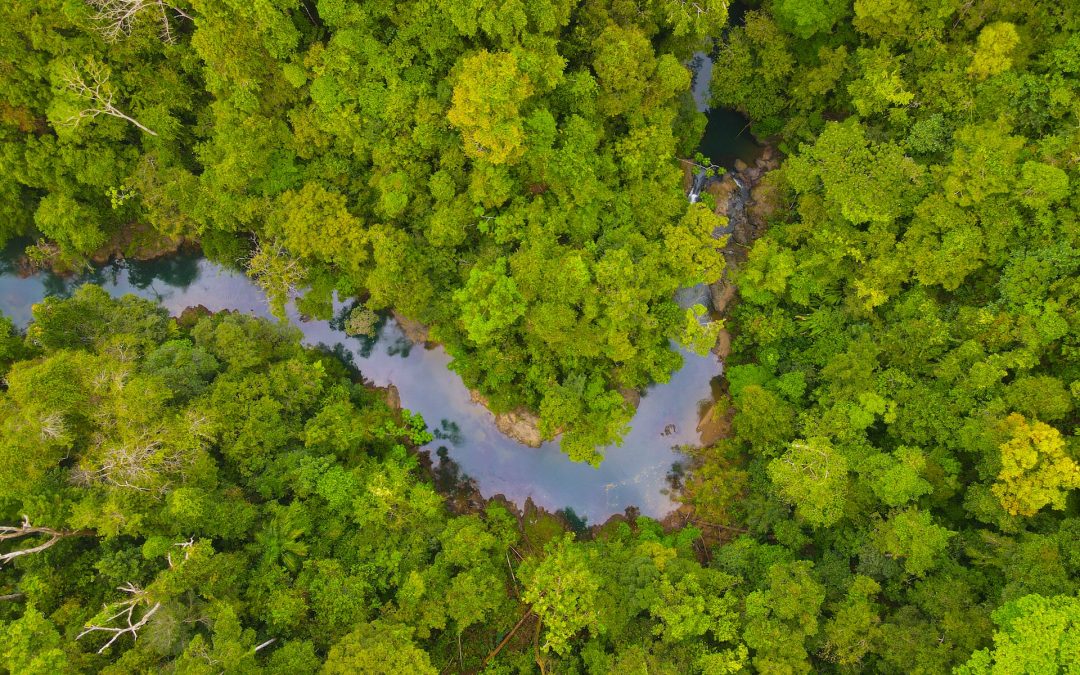

Maybe not. Take Costa Rica. A beautiful Central American country known for its lush rainforests and stunning beaches, Costa Rica proves that achieving high levels of human wellbeing has very little to do with GDP and almost everything to do with something very different.

Every few years the New Economics Foundation publishes the Happy Planet Index – a measure of progress that looks at life expectancy, wellbeing and equality rather than the narrow metric of GDP, and plots these measures against ecological impact. Costa Rica tops the list of countries every time. With a life expectancy of 79.1 years and levels of wellbeing in the top 7% of the world, Costa Rica matches many Scandinavian nations in these areas and neatly outperforms the United States. And it manages all of this with a GDP per capita of only $10,000, less than one-fifth that of the US.

In this sense, Costa Rica is the most efficient economy on earth: it produces high standards of living with low GDP and minimal pressure on the environment.

How do they do it? Professors Martínez-Franzoni and Sánchez-Ancochea argue that it’s all down to Costa Rica’s commitment to universalism: the principle that everyone – regardless of income – should have equal access to generous, high-quality social services as a basic right. A series of progressive governments started rolling out healthcare, education and social security in the 1940s and expanded these to the whole population from the 50s onward, after abolishing the military and freeing up more resources for social spending.

Costa Rica wasn’t alone in this effort, of course. Progressive governments elsewhere in Latin America made similar moves, but in nearly every case the US violently intervened to stop them for fear that “communist” ideas might scupper American interests in the region. Costa Rica escaped this fate by outwardly claiming to be anti-communist and – horribly – allowing US-backed forces to use the country as a base in the contra war against Nicaragua.

The upshot is that Costa Rica is one of only a few countries in the global South that enjoys robust universalism. It’s not perfect, however. Relatively high levels of income inequality make the economy less efficient than it otherwise might be. But the country’s achievements are still impressive. On the back of universal social policy, Costa Rica surpassed the US in life expectancy in the late 80s, when its GDP per capita was a mere tenth of America’s.

Today, Costa Rica is a thorn in the side of orthodox economics. The conventional wisdom holds that high GDP is essential for longevity: “wealthier is healthier”, as former World Bank chief economist Larry Summers put it in a famous paper. But Costa Rica shows that we can achieve human progress without much GDP at all, and therefore without triggering ecological collapse. In fact, the part of Costa Rica where people live the longest, happiest lives – the Nicoya Peninsula – is also the poorest, in terms of GDP per capita. Researchers have concluded that Nicoyans do so well not in spite of their “poverty”, but because of it – because their communities, environment and relationships haven’t been plowed over by industrial expansion.

All of this turns the usual growth narrative on its head. Henry Wallich, a former member of the US Federal Reserve Board, once pointed out that “growth is a substitute for redistribution”. And it’s true: most politicians would rather try to rev up the GDP and hope it trickles down than raise taxes on the rich and redistribute income into social goods. But a new generation of thinkers is ready to flip Wallich’s quip around: if growth is a substitute for redistribution, then redistribution can be a substitute for growth.

Costa Rica provides a hopeful model for any country that wants to chart its way out of poverty. But it also holds an important lesson for rich countries. Scientists tell us that if we want to avert dangerous climate change, high-consuming nations are going to have to scale down their bloated economies to get back in sync with the planet’s ecology, and fast. A widely-cited paper by scientists at the University of Manchester estimates it’s going to require downscaling of 4-6% per year.

This is what ecologists call “de-growth”. This calls for redistributing existing resources and investing in social goods in order to render growth unnecessary. Decommoditizing and universalizing healthcare, education and even housing would be a step in the right direction. Another would be a universal basic income – perhaps funded by taxes on carbon, land, resource extraction and financial transactions.

The opposite of growth isn’t austerity, or depression, or voluntary poverty. It is sharing what we already have, so we won’t need to plunder the earth for more.

Costa Rica proves that rich countries could theoretically ease their consumption by half or more while maintaining or even increasing their human development indicators. Of course, getting there would require that we devise a new economic system that doesn’t require endless growth just to stay afloat. That’s a challenge, to be sure, but it’s possible.

After all, once we have excellent healthcare, education, and affordable housing, what will endlessly more income growth gain us? Maybe bigger TVs, flashier cars, and expensive holidays. But not more happiness, or stronger communities, or more time with our families and friends. Not more peace or more stability, fresher air or cleaner rivers. Past a certain point, GDP gains us nothing when it comes to what really matters. In an age of climate change, where the pursuit of ever more GDP is actively dangerous, we need a different approach.

This essay originally appeared in The Guardian.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 9, 2017 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

by John McPhaul / Cultural Survival

On November 1, 2016, the Constitutional Chamber of Costa Rica’s Supreme Court provided some good news to a Terraba (Teribe) Indigenous territory when it stopped the state-run Costa Rica Electricity Institute (ICE by its Spanish acronym) from going forward with the Diquis hydroelectric project for failing to consult Indigenous communities who would see part of their lands flooded.

The permit, issued in 2007 under former President Oscar Arias, had declared the dam to be located at the mouth of the General River Valley in the southern Pacific and part of the country of “national interest.”

The court ruling did not question the “national interest” part of the permit, but said ICE had failed to comply with a previous high court order to adequately consult the Indigenous communities. The project has been stalled since 2011 over the Indigenous consultation issue.

The 650 megawatt hydroelectric project was to be the largest such project in Central America. The project’s reservoir would occupy 7363 hectares of land, 830 hectares of which are Indigenous territories, and displace over 1547 people.

The project would also flood 10 percent of the Terraba (also known as Teribe) China Kichá Indigenous territory (104 hectares) and 8 percent of another Terraba communities of Curré and Boruca (726 hectares). Officials estimate that 200 sacred Indigenous sites would be destroyed by the reservoir.

Some see the development as very positive. The $2.5 billion project would provide employment in the region to 3,500 people. The Diquis project would increase that renewable energy capacity and also allow Costa Rica to sell energy to neighboring Central American countries. Costa Ricans are proud of their electrical energy system which provides energy mostly from renewable resources. In 2016, the country went most of the year without resorting to using oil-fired thermal generators. But sometimes even renewable energy has high cost, especially when it comes to hydro-electric dams.

The high court ruling referred to Article 8 of the Arias Administration decree which would have allowed ICE to gather materials for the dam, power station, and connected works in locales in the areas of El General, Buenos Aires, Changuena and Cabagra, despite the fact that Indigenous people live in the areas.

According to the Constitutional Chamber’s press office, the annulled article was challenged previously in September of 2011, when the court determined that the decree was constitutional just as long as the Indigenous communities were consulted within a period of six months from the notification of the ruling.

However, early the next year, the court ruled that the six months established by the Court had passed and the consultation had not been made. “The Constitutional Chamber has demonstrated that, in fact, in the space of time established in the 2011-12975 ruling, the referred to consultation was not made nor did any party come to this Chamber request an extension of the time limit granted. Therefore, since the condition dictated in ruling 2011-12975 have not been met, the Article 8 of the No. 34312-MP-MINAE executive decree is unconstitutional because the consultation failed to occur,” said the press office.

The Terraba say they are not interested in the offers made so far to relocate their communities to other lands and provide them with well-paid jobs. “We don’t believe in the promises of employment for Indigenous Peoples, as up until today it had been demonstrated that all the qualified and best paid personnel have been brought from outside, Indigenous workers are used only to break rocks,” said community leader Jehry Rivera.

For Indigenous people, ICE offers are only opportunism. Indigenous Peoples want better lands and compensation in order to agree for the project to go forward.

The Court said that the consultation of Indigenous communities under Costa Rican law was necessary since the project is located in areas declared as an Indigenous reserve, “In fact, Costa Rica could be in violation of not complying with international conventions in relation to the autonomy of Indigenous Peoples over their territory. Costa Rica is a signatory of the International Labor Organization’s Convention on Indigenous and Tribal People.”

Indigenous Peoples are not the only ones opposed to the project. Environmentalists say that the dam’s reservoir would dry up the intensely green Térraba River Valley and would destroy irreplaceable habitats such as the Ramsar wetland and the river delta that drains into the Pacific. The wetlands and delta are the nesting grounds for many species including the endangered hump-back whale.

–John McPhaul is a Costa Rican-American freelance writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. During his many years in Costa Rica, the land of his birth, he wrote for the Miami Herald, Time Magazine and Costa Rica’s The Tico Times among other publications.

Photo by Florian Delée on Unsplash