By Tom Murphy / Do the Math

Whenever I suggest that humans might be better off living in a mode much closer to our original ecological context as small-band immediate-return hunter-gatherers, some heads inevitably explode, inviting a torrent of pushback. I have learned from my own head-exploding experiences that the phenomenon traces to a condition of multiple immediate reactions stumbling over each other as they vie for expression at the same time. The neurological traffic jam leaves us speechless—or stammering—as our brain sorts out who goes first.

One of the most common reactions is that abandoning agriculture is tantamount to committing many billions of people to death, since the planet can’t support billions of hunter-gatherers—especially given the dire toll on ecological health already accumulated.

Such a reaction definitely contains elements of truth, but also a few unexamined assumptions. The outcome need not be reprehensible for several reasons.

We All Die

Presumably this doesn’t come as a shock to anyone, but the 8 billion humans now on the planet are all going to die: every last one of them. This will happen no matter what. It’s inevitable. No one lives forever, or even much beyond a century.

Are we mortified by this news, intellectually? Of course not: our individual mortality comes as no great surprise. Some even accept it emotionally! So, there we go: whatever (realistic) proposal anyone else might offer for how humanity goes forward has the exact same consequence: OMG: you’ve just committed 8 billion people to die! You decide to have toast for breakfast? 8 billion people will end up dying. Nice going. Monster.

Timescales

I suspect that many strongly-negative reactions to suggestions that we adopt a “primitive” (ecologically-rooted) lifestyle trace to an implicit assumption about timescales. Maybe this is a result of our culture’s short-term focus on quarterly profits, short election cycles, or any other political proposal that tends to promise short- or intermediate-term results. So, perhaps it is assumed without question or curiosity that I am talking about a radical transition taking place over years or decades rather than centuries or even millennia. I would never…

Maybe I need to be better about pre-loading my discussion with this temporal context, since the assumption of short-term focus is so universal, and I get accused of misanthropy for something I never said—a running theme in this post. Abandoning agriculture need not happen overnight (and can’t, reasonably)!

Hypocrite!

Some of the angrier reactions suggest I volunteer to be one of those killed dead as part of my assumed/conjured “program,” or that I get my hypocritical @$$ out into the woods to eat lichen, naked. First of all, normal attrition, accompanied by sub-replacement fertility, is all it takes to whittle human population down, without requiring even a single premature death. And suppressed fertility needn’t be programmatically mandated like it was in China for a few decades: it’s happening on its own volition right now, around the globe. Roughly 70% of humans on the planet live in countries whose fertility rate is below replacement. It’s not a niche phenomenon, and presages a nearly-inevitable population downturn once the already-rolling train reaches the reproductive station in a generation’s time.

Part of the “you first” reaction, I believe, relates to our culture’s emphasis on the individual self. People automatically translate that I am asking them, personally, to become a hunter-gatherer or die. Again, I never said that, but it’s not unusual for people conditioned by our culture to take things personally, given ample reinforcement that we are each the deserving center of our own universe and little else matters. It is therefore understandable that members of modernity would assume (project) the same outlook is true for me. For those operating under this narrow (self-referential) assumption of how all others work, many valuable voices in the world must become baffling—or suspected of being disingenuous—which is a little sad.

When I point my passion toward avoiding a sixth mass extinction (which I interpret to include humans), I am not thinking about myself at all, but humans not yet born and species I don’t even know exist. My concern is focused on the health and happiness of a biodiverse, ecologically rich future. I myself am practically a lost cause as a product of modernity still trapped within its prison bars, and sure to die well before any of this resolves. Moreover, I can’t decide to roam the local lands hunting and gathering as long as property rights prevail and I do not enjoy membership in an ecological community operating outside the law. But, what I cando is try to get more people to wish for freedom, so that when opportunities arise good things can germinate in the cracks and force the cracks wider—even if I’m long gone when the crumbling process is complete. To repeat: it’s not about me. Talk of hypocrisy misses the boat entirely, by decades or centuries.

Not Even a Choice

Even if my audience gets over the shocked misimpression that I’m not talking about them personally, or a transition in their lifetimes, the objection can still remain strong. Isn’t keeping something like 8 billion humans alive indefinitely (via replacement in a steady demographic) far superior to something like 10–100 million hunter-gatherers living in misery?

First, the Hobbesian fallacy of believing foraging life to be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short” is so far off the mark and ignorantly uninformed as to be pitiable—but certainly understandable given our culture’s persistent programming on this point. Christopher Ryan’s Civilized to Death does a fantastic job dismantling this myth based on overwhelming anthropological evidence. Turns out we don’t get to fabricate stories of the past out of whole cloth (i.e., out of our meat-brains), without one bit of relevant knowledge or experience.

More broadly, if one’s worldview is that of a human supremacist (nearly universal in our culture, after all), then preservation of a ∼1010 human population makes complete sense: can’t have too much of a godly thing.

But we mustn’t forget that 8 billion humans are driving a sixth mass extinction, which leaves no room for even 10 humans if fully realized, let alone 1010. Deforestation, animal/plant population declines, and extinction rates are through the roof, along with a host of other existential perils. We have zero reason or evidence to believe (magically) that somehow 8 billion people could preserve modern living standards—reliant as they are on a steady flow of non-renewable extraction—while somehow not only arresting, but reversing the ominous ecological trends.

No serious, credible proposals to accomplish any such outcome are on the table: the play is to remain actively ignorant of the threat, facilitated by a narrow focus on this fleeting moment in time during which the modernity stunt has been performed. If ignorance did not prevail, we’d see retreat-oriented proposals coming out of our ears for how to mitigate/prevent the sixth mass extinction—but people say “the sixth what?” and go back to focusing on the Amazon that isn’t a dying rain forest. Most people know about climate change, but the dozens of “solutions” proposed to mitigate climate change amount to maintaining full power for modernity so that we motor-on at present course and speed under a different energy source. The IPCC never recommends orders-of-magnitude fewer humans or abandoning high-energy, high-resource-use lifestyles…because it would be political suicide—which says a lot about the limited value of such heavily-constrained institutions.

Saying that the planet (and humans as a part of it) would be better off with far fewer people can result in my being labeled a misanthrope, though I’ve never said I dislike people. I’ve heard it put nicely this way by several folks: I don’t hate people. I love them—just not all at the same time.

Quantitatively, 10–100 million humans on the planet for the next million years seems far preferable to 10 billion for only 100 or so more before the dominoes fall in a cascading ecological collapse at mass-extinction levels. Factoring in infant mortality and life expectancy among pre-historic people, a population of 10–100 million for a million years translates to roughly 200 billion to 2 trillion adults over time—far outweighing the total human life of 10 billion over a century or two.

Perhaps, then, I’m justified in turning the tables: reacting in horror to those who would propose to maintain a population of 8 billion, as this effectively condemns humans to a short tenure before mass extinction wipes us out. Why do proponents of maintaining present population levels hate humans so much? I’m actually serious!

Try this on: people love their kids, right? Let’s say that parents having 1–10 children are capable of expressing adequate love and providing adequate resources for all their kids. But if kids are so great, why not have 800 per family? You see, even great things cease to be great when the numbers are insane. 10–100 million humans can know a love and provision from Mother Earth that 8 billion surely will not. It’s madness, and our nurturing mother is being ravaged by the onslaught of the teeming, unloved—thus unloving—masses. Indeed, our culture wages war against the Community of Life, erroneously convinced that it was at war with us first. Yet, it created us, and nurtured us, or we would not be here!

Allowing normal demographic reduction to a sustainable population maximizes the total number of humans able to enjoy living on Earth. Now, I can’t really justify that as a valid metric—especially given our crimes against species—but I’m exposing my bias as a human (short of human supremacy: just expressing a preference that humans have some place on Earth rather than none). Not all human cultures have acted as destructively as ours, by a long shot, and many have considered Earth to be a generous, nurturing partner. Sustainable precedents liberally spread across a few million years at least somewhat justify the belief that humans canenjoy living on Earth without killing the host, and I’ll take what I can get.

Space Parallel

Tipped off by Rob Dietz of the Post Carbon Institute, I listened to a fantastic podcast episodecalled “The Green Cosmos: Gerard O’Neill’s Space Utopia”. In the last four minutes, professor of religion Mary-Jane Rubenstein reported that her students held an inverted sense of the impossible. To them, it was utterly impossible to imagine living on Earth with “nothing” (tech gadgets) as our ancestors actually really definitely did for millions of years, while not doubting the possibility that we could build space colonies in the asteroid belt and keep our devices and conveniences—despite nothing remotely of the sort ever being demonstrated. The delusion is fascinating, reminding me of Flat-Earthers, as featured in the insightful documentary “Behind the Curve.” Just as the earth looks flat to us on casual inspection, a few expensive stunts make it look to the faithful like we could someday colonize space. That’s right: I’m lumping space enthusiasts in with Flat-Earthers: enjoy each other’s company, folks!

But the base disconnect is very similar, here. Maintaining 8 billion human people on Earth is no more possible than invading space. It’s not an actual, realizable choice—beyond transitory and costly stunt demonstrations.

Hating the Likes?

The other head-exploding facet to the proposal of a much-reduced population living in something closer to our ecological context is that it would seem to amount to a callous repudiation of precious products of modernity: opera, symphony, great art, lunar landings, modern medicine, David Beckham’s right foot… Why do I hate these things? Well, I never said I did. Again with the words in my mouth… What I—or any of us—might like or dislike is completely irrelevant when it comes to biophysical reality and constraint.

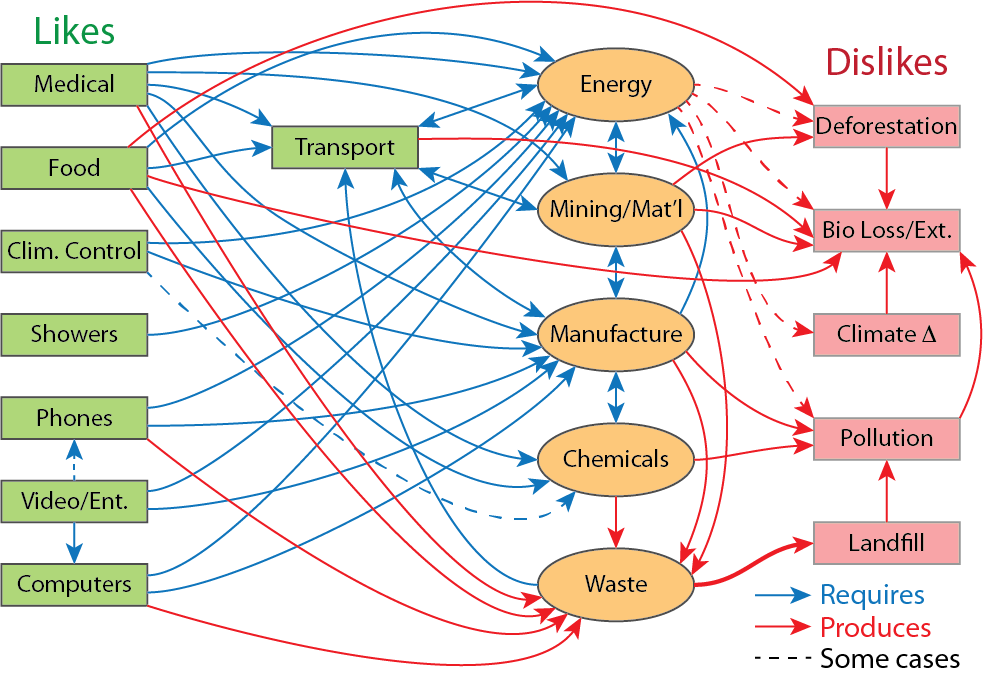

What makes us think we have a choice to separate the good from the bad, when they are most decidedly a package deal that we’ve been wholly unable to separate in practice, all this time? The following tangled figure—itself a staggering oversimplification of the actual mess—is repeated from an earlier post on Likes and Dislikes.

The fundamental flaw is that when faced with an unfamiliar landscape, our brains instantly and automatically assign separate qualities and features to a reality that in truth is inseparably inter-linked. Because the connections are numerous and often far from obvious, we are tricked into believing the entry-level mental model of separability. It’s the most basic and naïve (often adaptively useful) starting point to recognize a bunch of “things” without delving into the Gordian Knot of relationships. But that’s the easy part, and many stop there before it gets hard—often too hard for the very limited human brain, in fact. No blame, here: we all do it.

The Likes and Dislikes are a single phenomenon, having multiple interrelated aspects. Despite initial unexamined impressions, apparently we don’t actually get to choose to have modern medicine without advancing a sixth mass extinction. I’d give up a lot to prevent such a dire outcome—including modern medicine, since preserving it appears to translate to its own terminal diagnosis. Living seven decades is not rare in hunter-gatherer cultures; dental health is far better without agricultural products like grains and sugars dominating diets; and the chronic diseases we know too well in modernity are effectively absent for foraging folk (and notbecause lives are too short to expose them to the possibility—look deeper!). Modern medicine has extended adult life expectancy (once surviving infant mortality) maybe a decade or two, but at orders-of-magnitude greater per-capita ecological impact: a fatal “bargain” that calls to question our judgment.

Let the Standing Wave Stand

Some cloud patterns stay fixed relative to terrain—a coastline or mountain range/peak—even though the wind whisks along (see orographic and lenticular cloud formations). Moist air condenses at the leading edge, droplets careen through the formation, then evaporate on the trailing edge. These “standing wave” patterns are at once stationary and dynamic, with individual constituents playing a transitory role in a larger, more persistent phenomenon.

Human lives are similar: we flow into and out of life, while genetic patterns preserve a slowly-evolving human form across generations. The problem is that the magnitude and practices of the phenomenon are destroying the ecological conditions that allowed the phenomenon to arise and get so large in the first place. Our 8-billion-strong “cloud” is grossly unsustainable, so that it will collapse via its own downpour if not allowed to shrink. It’s possible to do so by natural attrition and generational transformation of lifestyles. While many factors threaten to make such a transition turbulent and “lossy,” the endpoint itself does not inherently demand a tortured path. Again, given modernity’s structural unsustainability, where we end up is not reallyan open choice. So, it’s best do what we can to make the only real positive outcome emerge as smoothly as it might: by embracing it and leaning into it rather than putting up a futile and destructive resistance that will hurt (all) lives far more than on the gentler path. Either way, 8 billion people will die. The bigger question is: will millions still live?

By Michael Dornbierer from Wikimedia Commons

WOW! A really great article. Thank you.

I would liike to point out a few more things not mentioned here:

The decline in fertility in the most industrialized countries is not as commonly assumed due mainly to people choosing to have fewer children. Sperm counts are way down, fertility clinics are doing a booming business, and governments giving financial incentives to try to get people to generate more cannon foder are not working. There is a major decline in the birth rate due, I think, mainly to chemical / nuclear pollution of the environment and food supply.

It is mainly in less industrialized countries like Africa that most population growth is now happening. In Europe, North America, And Japan, populations are shrinking.

Also, we should factor in the vast increase in people who may be physically capable of reproducttion but choose a form of sexual activity that cannot result in offspring. This too, is caused by chemical polltion of the environment, specificly, chemicals used to manufacture plastic, which when ingested by a pregnant woman at the stage of development when the hypothalamus of the fetus is forming, cause the resulting human to be homosexual or otherwise sexually aroused by the wrong sex or to self-identify as a member of the other sex. This form of prenatal brain damage is very frequent now and is an important componant of the decrease in the birth rate.

Civilization has worked itself into a fix. The global population is already much too big to be fed by organic type agriculture and it is only by the use of toxic chemicals, pesticides, herbicides, and artificial fertilizers, that there can be enough food to keep 8,0000,000,000 humans alive. So the choice comes down to either they must stop eating or eat poison.

I have read somewhere that in America, 50% of all adults have at least one chronic disease. 50%! And most of those diseases are caused by the pollutants civilization adds to the biosphere. Not only chemicals, but even more deadly, radioactivity and the unsensed but always present electromagnetic waves from all forms of electrical technology. To give one well-known example, cancer occurs in clusters around nuclear plants.

I have zero expectation of any significant number of humans deciding to change their way of living. That simply is not going to happen. The inevitable reduction in human numbers will not happen voluntarily, but it will happen. In fact, it is ALREADY happening NOW.

So the way things are going to work out is the humans are gfoing to cause a collapse that will recycle most of them back into the food chain and the few survivors will then be able to live as hunter gatherers on a recovering planet. But only if the recycling happens soon enough that anything is left to recover.

And, while I do not buy the common falacy that climate breakdown is caused by greenhouse gases from combustion, I do see evidence that there is a climate breakdown happening. I just do not agree that it is because of a so-called ”greenhouse effect”. I consider it to be mostly caused by radioactivity and elecromagnetic technologies of all kinds. But regardless of cause, there is a significant probability that within the next few decades, possibly even sooner, large-scale agriculture will become impossible in large parts of the world.

So I expect a big die-off of humans will happen relatively soon, though I cannot put an exact date on it. And the sooner it happens, the better. If it happens before too much more damage is done to what remains of the biosphere, there may be enough left to recover in the next few centuries. If civilization lasts too much longer, there will not be enough of the natural life-support systems left to start the recovery process.

”A thousand years from now, when all the cities long have crumbled into dust and wolves and grizlies stalk huge herds of bison across the unfenced plains, , little bands of hunters sitting by their lonely campfires in the wilderness will tell tales of the days when men flew through the air and liit up the night. And to be born among them will be the best of fates”.

Thanks for your comment on my comment Tzindaro. I agree with you – that the less the number of people eventually existing, the more that is truly of value in the modern world that we can retain. I did briefly think of paper consumption when I expressed a wish to not unnecessarily discard one of the favorite things for my personal life- algebra – a cognitive challenge built up over thousands of years of human effort. Of course the paper required could be replaced by a slate as in my parent’s school days or by a stick used in some smoothed sand. In the original article orchestral music was also mentioned as something that may have to be discarded along with other aspects of, material culture that imply much more consumption. That, I would also regret, even though its retention may require metal work and so mines. The primary problem is consumption – it must be reduced many fold – reducing both population and individual consumption would seem the best combination. However, some intermediate stage between small bands of hunter gatherers and the destructive juggernaut of the “civilisation” we have today, could be OK. We need to eliminate brainwashing throughout life to create artificial needs (that is advertising) That is we need to get rid of capitalism and make sure any other system, for me some form of socialism, that replaces it, does not feel the need for perpetual growth in competition with capitalist areas. However we may not need to go back to small bands of hunter-gatherers. In the absence of competitive growth crazed capitalism and with strong population contraction there may be the opportunity for both sustainability and retention of much that has developed that is truly a valuable contribution to a rich human life for humans of the future.

From my correspondence with a Marxist:

Hello, Petros,

At the link you sent me, you wrote

“What we need is an awakened population, self-organized and politically

mature, capable of REPLACING both Capital and the State. Capital can be

reabsorbed into society, into the womb that gave birth to it through the

labor of **billions** of people who will repossess it and operate its

**facillities** for **human** needs instead of profits. “………..

The three words I have marked with ** above are the crucial ones. The word “billions” assumes the impossible, namely, the continued existence on this finite planet of billions of people. The current population levels are simply not sustainable. The most important need right at this time in history is for a drastic reduction in population down to what the earth can support. No form of tinkering with the distribution system can change the sheer lack of enough air, water, forests, fish, and above all, living space. How it is divided among the population, evenly and fairly for all, or mainly for the benefit of a few rich individuals while the bulk of the population toil in poverty, is of secondary interest compared to the lack of enough to go around.

Freedom is inversely related to numbers, the more densely populated a region is, the less freedom the inhabitants can allow each other. Freedom is not and cannot be protected by laws and institutions. In fact, laws and institutions always work against freedom.

The second word, “facillities” implies that you expect factories, farms, schools, and other “facillities” to continue to exist in the new system. I doubt that. If people were healthy, rational, filled with the joy of life, and happy with their lives, there would not be any willing workers who would voluntarily spend their working lives deep underground in mines. So the new system would not have iron, coal, and all the other minerals needed to maintain an industrial technolgy.

Nor will it have mass production in factories on the current model. It will have plenty of skilled and creative craftsmen, but nobody willing to stand at an assembly line all day for any amount of payment. Healthy people simply will not do such work except at gunpoint. No amount of economic incentive could get them to do it. So any post-capitalist, post- consumerist society will also be a post-industrial one.

The third word, “human” is also problematical. If small children and hunter-gatherer tribes are any indicators, healthy people would not draw so big a distinction between so-called “humans” and people of other species. Specieism is an attitude indoctrinated into people in their childhood as a part of the programing they undergo to make them obedient tools of the system which depends on unquestioning exploitation of other species. There is no real difference between specieism and racism. I know you see this clearly in the case of racism, but you seem not to realize the same psychological and social mechanisms are at work in the pressure on children to learn to consider non-humans as non-people.

A future society based on human supremacism and human chauvinism, still exploiting all other species and their habitats as “resources” would still be a sick, oppressive culture, regardless of how it divided up the “resources” it usurped from the rest of the inhabitants of the ecosystem. And the few healthy people among them, if there are any, will still oppose any social order that considers all other species and their habitats “resources” to serve “human needs”.

In future, when anyone comes up with the predictable kneejerk responses enumerated in this article, I shall just refer them to this article. (Wait! The majority of people don’t do longform reading anymore and if it can’t be “discussed” in a soundbite aren’t interested!)

PS: just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean its a “fallacy” — whether overpopulation or anthropogenic climate change.

I could have written this with two exceptions:

Considering that humans fit the medical definition of being a cancerous tumor on the Earth — Sixth Great Extinction, destruction of entire ecosystems, pollution of the entire planet, a wanton disregard for nonhumans, etc. — I see nothing wrong with being misanthropic. It doesn’t make for good PR and I certainly wouldn’t emphasize it if you’re trying to convince anyone, but you don’t have to criticize it or equivocate.

A few million people limited to the tropics (where humans belong) is plenty. 100 million would be ten times too many, no idea where Tom Murphy got that number from.

Otherwise, great essay, I totally agree. I get the same objections when I mention human overpopulation.

He got that number from the number of sq. kilometers of land on this planet, and the usual estimates by anthropologists of how much land area per hunter-gatherer is needed. But the estimate ignores any diferences between tropical junge and deserts or Arctic tundra, so it should be sharply revised downwards. Your suggested number is much more realistic.

Agree with most of the wisdom in this excellent article. However there are some things that I value that would be needlessly lost if all the modern world eventually evapourated. A lot of culture does not imply material consumption, (although it will often require human society to be organised to a degree). Personally I would feel sorrow if I knew that humans of the future were not able to enjoy the mental challenges that have emerged from thousands of years development of abstract algebra, This requires only pencil and paper. Most topics in algebra do not facilitate the modern world

Paper requires trees. In fact, the invention of the printing press resulted in massive deforestation in Europe.

I personally flunked algebra three times, so I do not share your enthusiasm for it, but I like to read science fiction. However, I would be willing to give it up to live in a world with vast forests and plenty of wildlife.

The real issue is not what can or cannot exist in such a world. The real issue is that nothing can exist in a world with billions and billions of excess people. If the number of humans was compatible with the biosphere those few people could have anything and everything without doing much harm to themselves of anything else. But no lifestyle is viable with too many people living it, no matter how little harm each single one does.