by Andrew Nikiforuk / Local Futures

By now you have probably read about the so-called “tech backlash.” Facebook and other social media have undermined what’s left of the illusion of democracy, while smartphones damage young brains and erode the nature of discourse in the family. Meanwhile computers and other gadgets have diminished our attention spans along with our ever-failing connection to reality.

The Foundation for Responsible Robotics recently created a small stir by asking if “sexual intimacy with robots could lead to greater social isolation.” What could possibly go wrong?

The average teenager now works about two hours of every day – for free – providing Facebook and other social media companies with all the data they need to engineer young people’s behavior for bigger Internet profits. Without shame, technical wonks now talk of building artificial scientists to resolve climate change, poverty and, yes, even fake news.

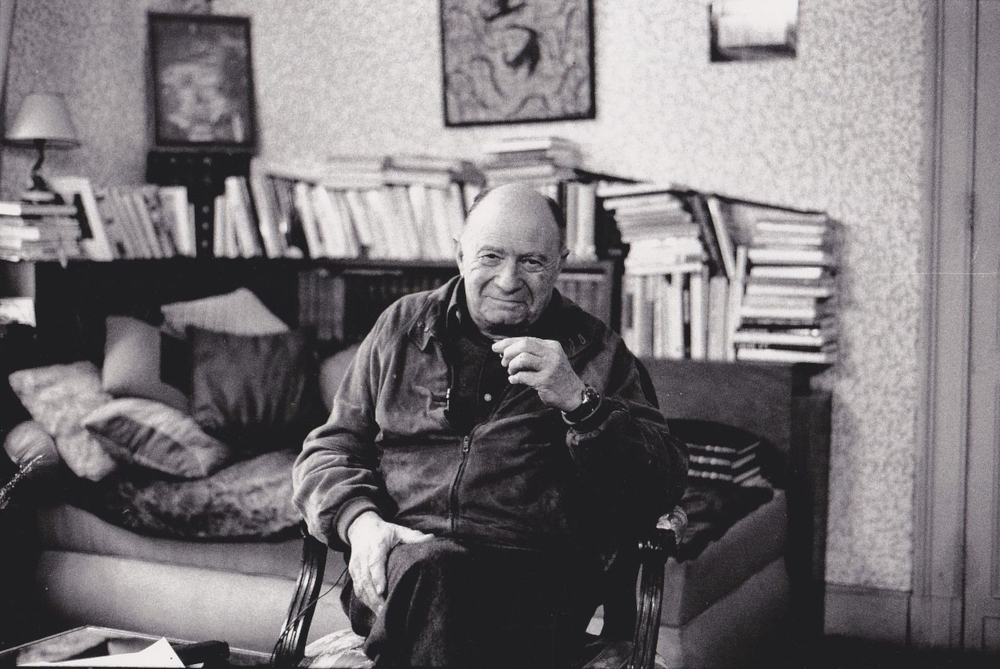

The media backlash against Silicon Valley and its peevish moguls, however, typically ends with nothing more radical than an earnest call for regulation or a break-up of Internet monopolies such as Facebook and Google. The problem, however, is much graver, and it is telling that most of the backlash stories invariably omit any mention of technology’s greatest critic, Jacques Ellul.

The ascent of technology

Ellul, the Karl Marx of the 20th century, predicted the chaotic tyranny many of us now pretend is the good and determined life in technological society. He wrote of technique, about which he meant more than just technology, machines and digital gadgets but rather “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency” in the economic, social and political affairs of civilization.

For Ellul, technique, an ensemble of machine-based means, included administrative systems, medical tools, propaganda (just another communication technique) and genetic engineering. The list is endless because technique, or what most of us would just call technology, has become the artificial blood of modern civilization. “Technique has taken substance,” wrote Ellul, and “it has become a reality in itself. It is no longer merely a means and an intermediary. It is an object in itself, an independent reality with which we must reckon.”

Just as Marx deftly outlined how capitalism threw up new social classes, political institutions and economic powers in the 19th century, Ellul charted the ascent of technology and its impact on politics, society and economics in the 20th. My copy of Ellul’s The Technological Society has yellowed with age, but it remains one of the most important books I own. Why? Because it explains the nightmarish hold technology has on every aspect of life, and also remains a guide to the perplexing determinism that technology imposes on life.

Until the 18th century, technical progress occurred slowly and with restraint. But with the Industrial Revolution it morphed into something overwhelming – due in part to population, cheap energy sources and capitalism itself. Since then it has engulfed Western civilization and become the globe’s greatest colonizing force. “Technique encompasses the totality of present-day society,” wrote Ellul. “Man is caught like a fly in a bottle. His attempts at culture, freedom, and creative endeavor have become mere entries in technique’s filing cabinet.”

Ellul, a brilliant historian, wrote like a physician caught in the middle of a plague or physicist exposed to radioactivity. He parsed the dynamics of technology with a cold lucidity. Yet you’ve probably never heard of the French legal scholar and sociologist despite all the recent media about the corrosive influence of Silicon Valley. His relative obscurity has many roots. He didn’t hail from Paris, but rural Bordeaux. He didn’t come from French blue blood; he was a “meteque.” He didn’t travel much, criticized politics of every stripe and was a radical Christian.

But in 1954, just a year before American scientists started working on artificial intelligence, Ellul wrote his monumental book, The Technological Society. This dense and discursive work lays out in 500 pages how technique became for civilization what British colonialism was for parts of 19th-century Africa: a force of total domination.

Ellul didn’t regard technology as inherently evil; he just recognized that it was a self-augmenting force that engineered the world on its terms. Machines, whether mechanical or digital, aren’t interested in truth, beauty or justice. Their goal is to make the world a more efficient place for more machines. Their proliferation, combined with our growing dependence on their services, inevitably led to an erosion of human freedom and unintended consequences in every sphere of life.

Ellul was one of the first to note that you couldn’t distinguish between bad and good effects of technology. There were just effects and all technologies were disruptive. In other words, it doesn’t matter if a drone is delivering a bomb or book or merely spying on the neighborhood, because technique operates outside of human morality: “Technique tolerates no judgment from without and accepts no limitations.”

Facebook’s mantra “move fast and break things” epitomizes the technological mindset. But some former Facebook executives such as Chamath Palihapitiya belatedly realized they have engineered a force beyond their control. (“The short-term dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works,” Palihapitiya has said.) That, argued Ellul, is what technology does. It disrupts and then disrupts again with unforeseen consequences, requiring more techniques to solve the problems created by the last innovation. As Ellul noted back in 1954, “History shows that every technical application from its beginnings presents certain unforeseeable secondary effects which are more disastrous than the lack of the technique would have been.”

Ellul also defined the key characteristics of technology. For starters, the world of technique imposes a rational and mechanical order on all things. It embraces artificiality and seeks to replace all natural systems with engineered ones. In a technological society a dam performs better than a running river, a car takes the place of pedestrians – and may even kill them – and a fish farm offers more “efficiencies” than a natural wild salmon migration.

There is more:

- Technique automatically reduces actions to the “one best way.”

- Technical progress is self-augmenting: it is irreversible and builds with a geometric progression. (Just count the number of gadgets telling you what to do or where to go or even what music to play.)

- Technology is indivisible and universal because everywhere it goes it shows the same deterministic face with the same consequences.

- It is autonomous, by which Ellul meant that technology has become a determining force that “elicits and conditions social, political and economic change.”

The role of propaganda

The French critic was the first to note that technologies build upon each other and therefore centralize power and control. New techniques for teaching, selling things or organizing political parties also required propaganda. Here again Ellul saw the future. He argued that in a technological society, propaganda had to become as natural as breathing air because it was essential that people adapt to the disruptions of a technological society. “The passions it provokes – which exist in everybody – are amplified. The suppression of the critical faculty – man’s growing incapacity to distinguish truth from falsehood, the individual from the collectivity, action from talk, reality from statistics, and so on – is one of the most evident results of the technical power of propaganda.” Faking the news may have been a common practice on Soviet radio during Ellul’s day, but it is now a global phenomenon leading us towards what Ellul called “a sham universe.”

We now know that algorithms control every aspect of digital life and have subjected almost aspect of human behavior to greater control by techniques, whether employed by the state or the marketplace. But in 1954 Ellul saw the beast emerging in infant form. Technology, he wrote, can’t put up with human values and “must necessarily don mathematical vestments. Everything in human life that does not lend itself to mathematical treatment must be excluded… Who is too blind to not see that a profound mutation is being advocated here?”

He also warned about the promise of leisure provided by the mechanization and automatization of work. “Instead of being a vacuum representing a break with society,” our leisure time will be “literally stuffed with technical mechanisms of compensation and integration.” Good citizens today now leave their screens at work only to be guided by robots in their cars that tell them the most efficient route to drive home. At home another battery of screens awaits to deliver entertainments and distractions, including apps that might deliver a pizza to the door. Stalin and Mao would be impressed – or perhaps disappointed – that so much social control could be exercised with such sophistication and so little bloodletting.

Ellul wasn’t just worried about the impact of a single gadget such as the television or the phone but “the phenomenon of technical convergence.” He feared the impact of systems or complexes of techniques on human society and warned the result could only be “an operational totalitarianism.” “Convergence,” he wrote, “is a completely spontaneous phenomenon, representing a normal stage in the evolution of technique.” Social media, a web of behavioral and psychological systems, is just the latest example of convergence. Here psychological techniques, surveillance techniques and propaganda have all merged to give the Russians and many other groups a golden opportunity to intervene in the political lives of 138 million North American voters.

Social media has achieved something novel, according to former Facebook engineer Sam Lessin. For the first time ever a political candidate or party can “effectively talk to each individual voter privately in their own home and tell them exactly what they want to hear… in a way that can’t be tracked or audited.” In China the authorities have gone one step further. Using the Internet the government can now track the movements of every citizen and rank their political trustworthiness based on their history of purchases and associations.

The Silicon Valley moguls and the digerati promised something less totalitarian. They swore that social media would help citizens fight bad governments and would connect all of us. Facebook, vowed the pathologically adolescent Mark Zuckerberg, would help the Internet become “a force for peace in the world.” But technology obeys its own rules and prefers “the psychology of tyranny.”

The digerati also promised that digital technologies would usher in a new era of decentralization and undo what mechanical technologies have already done: centralize everything into big companies, big boxes and big government. Technology assuredly fragments human communities, but in the world of technique centralization remains the norm. “The idea of effecting decentralization while maintaining technical progress is purely utopian,” wrote Ellul.

Towards ‘hypernormalization’

It is worth noting that the word “normal” didn’t come into currency until the 1940s, along with technological society.

In many respects global society resembles the Soviet Union just prior to its collapse, when “hypernormalization” ruled the day. A recent documentary defined what hypernormalization did for Russia: it “became a society where everyone knew that what their leaders said was not real, because they could see with their own eyes that the economy was falling apart. But everybody had to play along and pretend that it was real because no one could imagine any alternative.”

In many respects technology has hypernormalized a technological society in which citizens exercise less and less control over their lives every day and can’t imagine anything different. If you are growing more anxious about our hypernormalized existence and are wondering why you own a phone that tracks your every movement, then read The Technological Society. Ellul believed that the first act of freedom a citizen can exercise is to recognize the necessity of understanding technique and its colonizing powers. Resistance, which is never futile, can only begin by becoming aware and bearing witness to the totalitarian nature of technological society.

To Ellul, resistance meant teaching people how to be conscious amphibians, with one foot in traditional human societies, and to purposefully choose which technologies to bring into their communities. Only citizens who remain connected to traditional human societies can see, hear and understand the disquiet of the smartphone blitzkrieg or the Internet circus. Children raised by screens and vaccinated only by technology will not have the capacity to resist, let alone understand, this world any more than someone born in space could appreciate what it means to walk in a forest.

Ellul warned that if each of us abdicates our human responsibilities and leads a trivial existence in a technological society, then we will betray freedom. And what is freedom but the ability to overcome and transcend the dictates of necessity?

In 1954, Ellul appealed to all sleepers to awake. Read him. He remains the most revolutionary, prophetic and dangerous voice of this or any century.

This essay originally appeared in The Tyee, and republished by Local Futures. Republished with permission of Local Futures. For permission to repost this or any other Local Futures blog, please contact them directly at info@localfutures.org

Andrew Nikiforuk has written about energy, economics and the West for a variety of Canadian publications including T he Walrus, Maclean’s, Canadian Business, The Globe and Mail, Chatelaine, Georgia Straight, Equinox and Harrowsmith . His latest book is The Energy of Slaves: Oil and the New Servitude.Photo by Jan van Boeckel, ReRun Productions, Creative Commons licensed ( CC BY-SA 4.0).