by Courtney Parker / Intercontinental Cry

For over 6 years now, environmental defenders representing the Unist’ot’en, an official faction of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, have been standing guard over their traditional territory from invasion by Transcanada’s Coastal Gaslink pipeline.

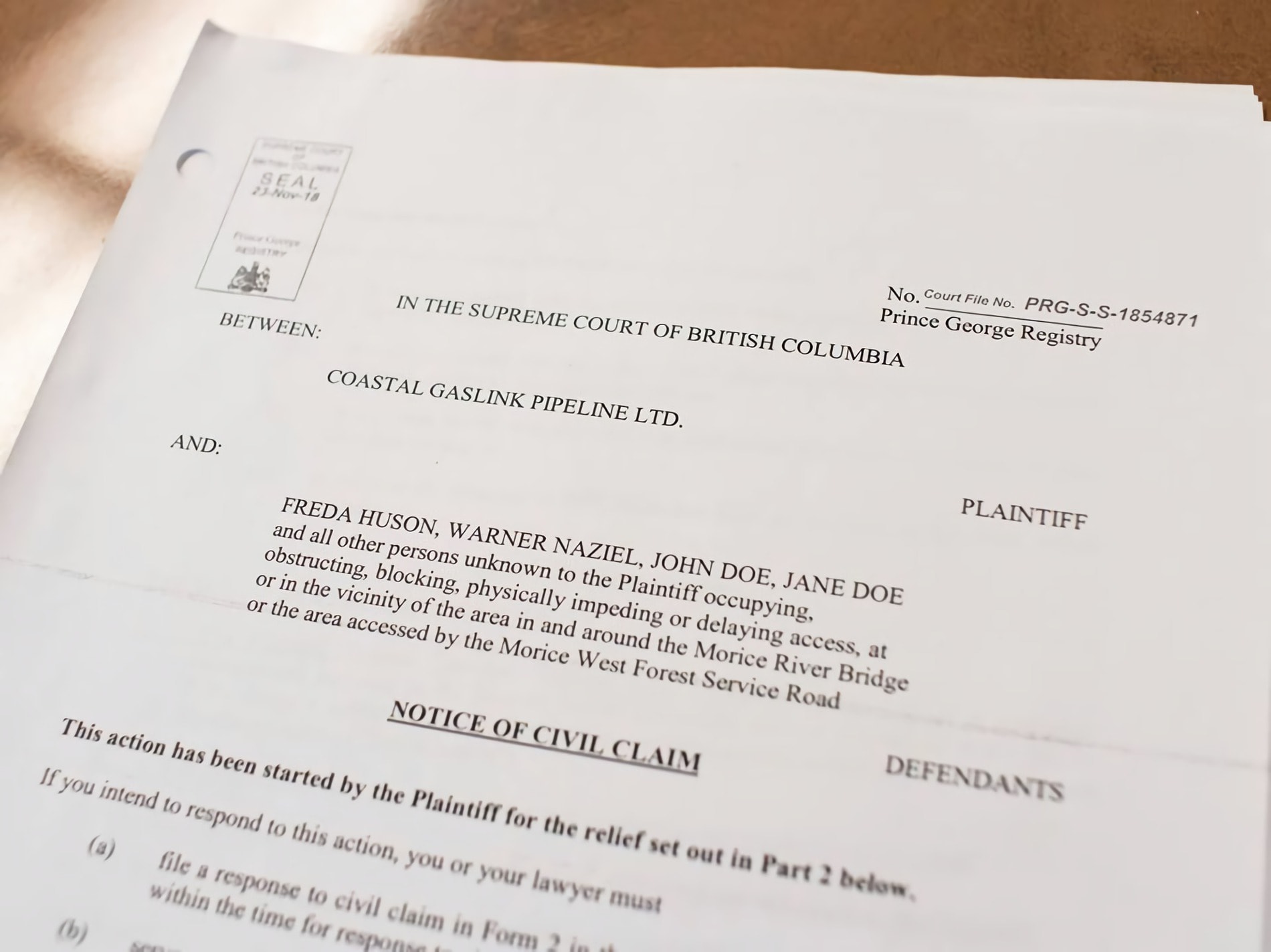

On December 14, 2018, a British Columbia Supreme Court Justice levied a temporary injunction, ordering an end to the blockade — bypassing the required consent of tribal leaders.

Prior to this, a gated blockade had prevented pipeline workers from trespassing onto First Nation lands through the Morice River bridge — located on a forest road.

The injunction, which demands environmental defenders vacate their stronghold of resistance to the planned 670 kilometer pipeline, is set to start on Monday, December 17th, allowing pipeline workers free passage until May 2019.

In a show of quasi-generosity, Coastal Gaslink has stated that the camp connected to the blockade may remain in place… as long as they discontinue any obstruction of pre-construction traffic through the gated area.

“Right now, our focus is on respectfully and safely moving forward with project activities, including gaining safe access across the Morice River bridge … We simply ask that their activities do not disrupt or jeopardize the safety of our employees and contractors, surrounding communities or even themselves,” Coastal GasLink said in a statement.

Representatives of Coastal Gaslink have also cited an inability of First Nation communities to provide restitution for any ‘losses’ the company could incur through delays or obstructions to construction plans as support for the injunction and enforcement order.

Yet, enforcement of the project remains dubious given that the territory has never changed hands via treaty, nor have land rights ever been conceded in any manner. In effect, the right of the Unist’ot’en People to determine the fate of their ancestral land remains intact.

This also makes the injunction a clear violation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) which requires ‘free, prior and informed consent’ (FPIC) when it comes to development, investment or extraction initiatives on Indigenous territories.

The area in question has been occupied by the Unist’ot’en for generations; their current leader, Chief Knedebeas, describes occupying and carrying out tribal traditions there since his childhood.

Now, the territory under threat is being used as a crucial healing center where Wet’suwet’en people are receiving treatment for addiction. Freda Hudson, Unist’ot’en clan, explained:

“The Unist’ot’en Healing Centre was constructed to fulfill their vision of a culturally-safe healing program, centred on the healing properties of the land. It is the embodiment of self-determined wellness and decolonization, with potential to build up culture-based resiliency of Indigenous people who need support, through re-establishing relationships with land, ancestors and the underlying universal teachings that connect distinct Indigenous communities across the world.”

The Unist’ot’en have until January 31, 2019 to respond to Coastal Gaslink’s application.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks