by Jo Woodman and Alicia Kroemer / Intercontinental Cry

On September 30, communities across Canada will be commemorating ‘Orange Shirt Day’, an annual event that is helping Canadians remember the thousands of Indigenous children who died in Residential Schools, and to reflect on the intergenerational trauma that was caused by the Residential school system. Similar school systems were also run in the US, New Zealand and Australia with terrible consequences for Indigenous children and communities.

Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation elder Phyllis Jack Webstad founded Orange Shirt Day in 2013, after she shared her childhood experience at the St. Joseph’s Mission residential school in William’s lake, British Columbia.

Residential school staff stripped her of her favourite orange shirt the day she was taken from her family. As Residential school survivor Vivian Timmins said today, “The orange day shirt is a commonality for all Native Residential School Survivors because we had our personal items taken away which was a tactic to erase our personal identity. Maybe it was a piece of clothing, but it represented our memory that connected us to families. Today is a time to honour the children and youth that didn’t make it home. It’s a time to remember Canada’s dark history, to educate and ensure such history is never repeated.”

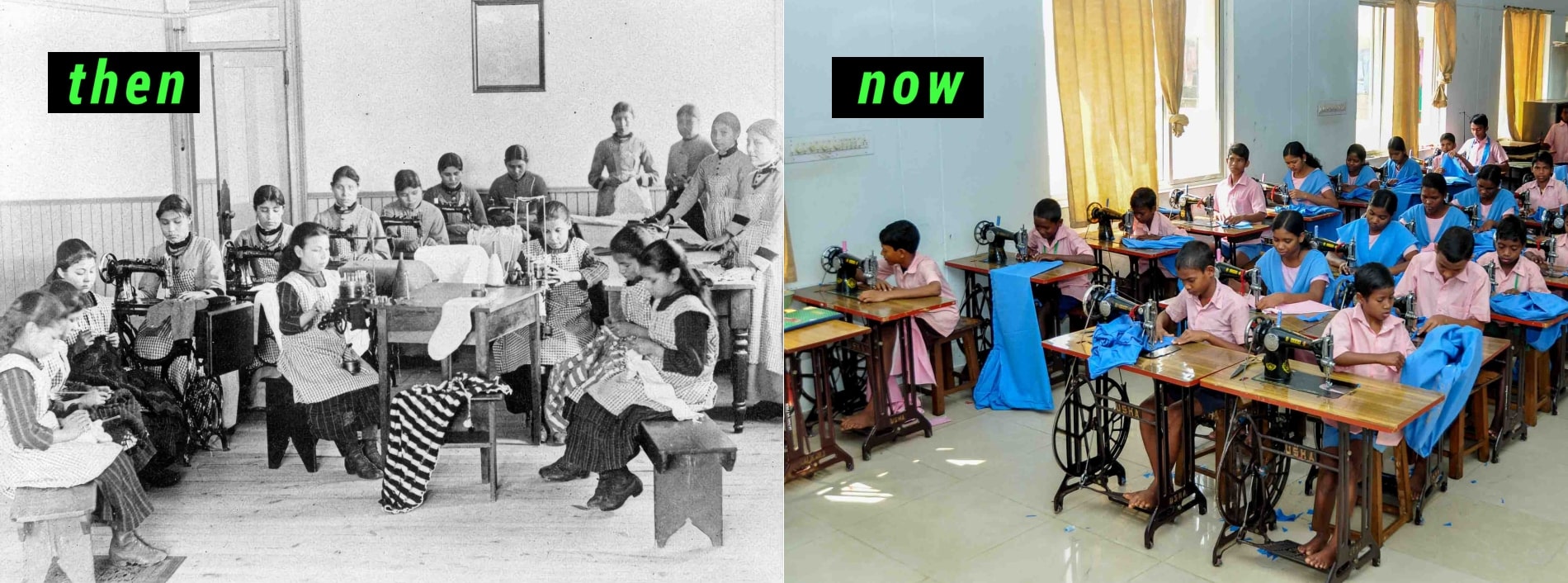

Alarmingly, that history is being repeated in many parts of the world. According to Survival International, there are nearly one million tribal and Indigenous children across Asia, Africa, and South America who are currently attending institutions that bear a striking resemblance to Canada’s residential schools.

Indigenous artist RG Miller’s haunting autobiographical painting recalls the horrific abuse he experienced at residential school. Photo Courtesy RG Miller

A horrifying legacy lives on

The horrifying legacy of residential schools is being repeated, on a massive scale, because the attitudes and intentions underlying Canada’s residential school system live on.

Tribal and Indigenous children around the world are being coerced from their families and sent to schools that strip them of their identity and often impose upon them alien names, religions, and languages.

Extractive industries and fundamentalist religious organizations are frequently pulling the strings behind these institutions.

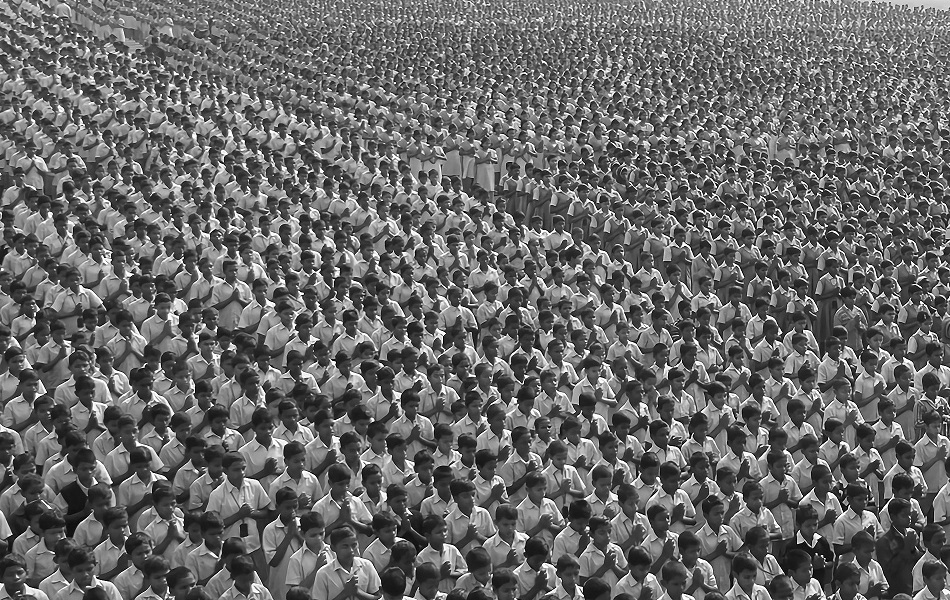

One residential mega-school in India—which boasts it is “home” to 27,000 Indigenous children—states publicly that it aims to turn “primitive” tribal children from “liabilities into assets, tax consumers into tax payers.”

Its partners include the very mining companies that are trying to wrest control of the lands these children truly call home.

Parents have described the school as a “chicken farm” where children feel like “prisoners.”

An expert on Adivasi education told us, “Their whole minds have been brainwashed by a kind of education that says, ‘Mining is good’, ‘Consumerism is good’, ‘Your culture is bad.’ Tribal residential schools are institutions which are erasing the autobiography of each child to replace it with what fits the ‘mainstream’. Isn’t it a crime in the name of schooling?”

Without urgent change, many distinct peoples could be wiped out in just a few generations, because the the youth in these schools are taught to see their families and traditions as ‘primitive’, ‘backward’ and inferior to ‘mainstream’ society so that they turn their backs on their languages, religions and lands.

Survivors of Canada’s residential schools are beginning to speak out against these culture-destroying institutions.

“What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada”, says Roberta Hill

Roberta Hill is a survivor of the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Canada, where she was abused by the pastor and school staff in the 1950s and 60s. She sees the strong parallels between her experience and that of Indigenous children in these modern culture destroying schools: “What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada – this separation of Indigenous children from their family, language, and culture is a very destructive force. My experience at residential school was traumatizing. I was taken from my family at the age of six and put in the school where I experienced a lot of abuse and isolation. If this is happening again now, then there needs to be international attention. It needs to stop or else they are going to go through the same thing that we went through. It will cause irreparable damage – not only to the Indigenous children attending, but to the future generations of that community.”

RG Miller, a prominent Indigenous artist from Canada states: “My horrific experience at Native residential school destroyed my connection with community, family, and my culture. The abuses I suffered there completely broke any sense of trust or intimacy with anyone or anything including God, spouses, and children for the rest of my life.”

Over the past two decades, thousands of residential school survivors have shared their stories of abuse; but there are thousands of other children who will never be able to tell their own stories because they passed away while they were in a residential school. Other children, like Chanie Wenjack, died while trying to escape. The young Ojibwe boy ran away from his residential school in Ontario, trying desperately to reach home, 600 km away. He died of hunger and exposure at the age of 12 in 1966.

Half a century later—and 12,000km away—Norieen Yaakob, her brother Haikal and five of their friends, fled their residential school in Malaysia. The children, who belong to the Temiar—one of the Orang Asli tribes of central Malaysia—ran away to avoid a beating from their teacher. 47 days later, Norieen and one other little girl were found, starving but alive. The other five children died, including Haikal and seven-year-old Juvina.

Juvina’s father, David, told us, “The police said, “Why are you bothering us with this problem?” We felt hopeless. It was only on the sixth day that the authorities began their search and rescue mission for the children. But they told us parents to stay behind. They said if we went in it would just be to secretly give food to the missing children that we were supposedly hiding. They accused us of faking the whole incident to gain attention and force the government to help us more. That was what they thought of us… [Finally] they found a child’s skull and we could not identify immediately whose child it was. We had to wait for the post-mortem. I could not recognize my own child.” The families are currently taking the authorities to court in a case that the world should be watching.

Norieen Yaakob of the Temiar tribe of Malaysia barely survived running away from her residential school. She was found 47 days after fleeing her school; five other children died.

The terrible truth is that Indigenous children are dying in these schools. In tribal residential schools in Maharashtra state in India, over one thousand deaths have been recorded since 2000, including many suicides. With echoes of the traumas experienced in Canada, many parents never learn that their children are ill until it is too late, and they often never know the cause of death.

There are also a frightening number of cases of physical and sexual abuse, very few of which reach the justice system. Government schools across Asia and Africa are often staffed by teachers who have no connection to, or respect for, the communities they serve. Teacher absences are common, and abuse goes unseen and unreported. The potential for devastating damage is extremely high.

Survival International will soon launch a campaign to expose and oppose these culture destroying schools and to demand greater Indigenous control of education, before it is too late for these children, their communities, and their futures.

There is certainly a need for it. These schools endanger lives and strip away identities, but they also deny children the right to choose a tribal future.

The ability of Indigenous Peoples to live well and sustainably on their lands depends on their intricate knowledge, which takes generations to develop and a lifetime to master. To survive and thrive in the Kalahari Desert or to herd reindeer across the Arctic tundra cannot be learnt in residential schools, or on occasional school vacations.

What’s more, in this current age of severe environmental degradation, climate change and mass extinctions, Indigenous Peoples play a crucial role in preserving the world’s ecosystems. They are the best guardians of their lands and they should be respected and listened to if we have any hope of survival for future generations.

Rather than erasing their knowledge, skills, languages, and wisdom through culture-destroying residential schools, we must allow them to be the authors of their own destinies as stewards and protectors of their own lands.

Tribal children in Indonesia learning on their land, in their language. Photo: Sokola Rimba

Dr. Jo Woodman is running Survival International’s upcoming Indigenous Education campaign. She has spent two decades researching and campaigning on Indigenous rights issues, focused on the impacts of forced ‘development’, conservation and schooling on tribal communities.

Alicia Kroemer holds a PhD in political science from the university of Vienna on collective memory and residential schools in Canada, with publications, films, and lectures on the topic. She serves on the board of Indigenous rights NGO Incomindios in Zurich, where she is a human rights educator and UN representative. She also works as a research consultant for Minority Rights Group and Survival International in London, UK. She is interested in allyship, advocating and promoting human rights, with a special focus on Indigenous rights globally.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks