Caste-based discrimination and violence has been prevalent in Nepalese society for a long time. Although both have been made illegal, Salonika explains why incidents occur, highlighting the harmful system that maintains the violence.

Is Casteism dead in Nepal?

By Salonika

May 23, 2020 marks the nine-year anniversary of the day when the parliament passed a law against caste-based discrimination in Nepal. The day was marked by two incidents that highlight how far caste-based hierarchy is from elimination from the Nepalese society.

A young Dalit man, planning to elope with his “higher”-caste girlfriend arrived at the woman’s village with a group of seventeen friends. Some days later, the bodies of five men from the group were found floating in the Bheri river. One of them is still missing. On the day of the planned elopement, the group was met by a mob of “upper”-caste members who brutally thrashed them to death.

The body of a Dalit girl (aged 13) was found hanging from a tree near her in-law’s house. The girl had been married to her 25-year old rapist (from a “higher” caste) earlier the same day, at the behest of the local authorities. The girl was beaten by her in-laws before her death.

These incidents are not isolated. Violence against marginalized groups like Dalits have been persistent in the Nepalese society. Privileged groups have turned a blind eye to this for a long time. They refuse to see relationship to caste in such incidents, interpreting as solely criminal cases. Unfortunately, when the cases get legal attention, that is how they are labeled instead of a form of systemic oppression. I would argue that the caste of the victims, at least in these two cases, are a salient feature.

Caste system

Caste system has a strong historical root in the Indian subcontinent. It first originated as an open form of social organization. A person’s caste was determined by the work they did, i.e. their function in the society. However, over time, the system became a closed one. The caste of a person (as well as the work they did in the society) became based on the family they were born into. With changing times, a person’s work is no longer determined by their caste, but their caste is still determined by their birth. The rigid hierarchy still prevails.

Like every form of oppression, the caste system has dehumanized the oppressed group. The Dalit group, which occupies the lowest rung of that hierarchy, historically, have been barred from basic civil rights. They were not allowed to touch the water source of the so-called “higher”-castes. They were not allowed to enter temples. The dehumanization then becomes a justification for the group’s oppression, which has been perpetuated by the entire culture.

This caste based hierarchy has also translated to an economic and political hierarchy. Previously, the Dalits were not supposed to own money, relying on Brahmins and Chetris, whom they provided services to, for basic necessities. This has stripped them of considerable economic power. The same is true for political power. Even today, they are overrepresented among those living in poverty, and underrepresented in positions of authorities.

Crimes like honor killings, rapes, and domestic violence against newly married brides occur across all castes in Nepal. Caste is often a salient feature in particular crimes.

Caste-exogamy in marriage

Nepalese society still values caste-endogamy in marriage, that is, marriage among people of the same caste. In both cases described above, the marriages were exogamous. In the case of the young couple, a “higher”-caste woman was planning on eloping with a “lower”-caste man. Had the elopement been successful, it would have brought disgrace not only to the woman’s family, but to her entire community. It was perhaps to ‘protect the community’ from that disgrace that five young men were beaten to death.

Similarly, when the adolescent girl reached the home of her abuser, she was physically abused by the man’s family. The crimes of the man were not visible to his family members, neither was the suffering of a child who was forced to marry the man who exploited and raped her. Instead, they beat the girl because a low-caste girl was about to become their daughter-in-law.

Whether it is the marriage of a ‘higher’-caste woman with a ’lower’-caste man, or of a ‘higher’-caste man with a ’lower’-caste girl, it is the ’lower’-caste individual who has been the victim of the violence at the hands of the family of the other.

Involvement of authorities

After the rape of an adolescent girl, instead of reporting a First Investigation Report (FIR), the society’s idea of a punishment was to ensure the rapist marry the girl. The local representative held the same view. In fact, no official complaint was registered, neither in the local representative’s office, nor with the police authority. Due to this, the representative is now denying any role in approving the marriage of the perpetrator to his victim.

The local representative had a more direct role in the case of the five dead men. The representative is among the twenty people named by the victim’s family as part of the mob that beat and killed their son. Although all twenty of them are currently under police custody, the actions of police administration in cases of ’lower’-caste victims is inadequate.

After being brutally abused by her rapist’s family, the girl’s body was found hanging with clear marks of physical violence. The police authority failed to register the crime, stating that the girl had killed herself. Usually, even clear suicide cases are registered by the police in Nepal for investigation. It was only after four days that the case was finally registered, after pressures from activists. Even after the man has been registered as the prime accused, the police have not yet arrested him.

“Often the police refuse to even register cases - such as rape - when the victim is a Dalit.” -Meenakshi Ganguly, Human Rights Watch

This is not an isolated event either. Oftentimes, police try to settle matters without registering a case if the victim is from the Dalit community. Even when they do, the chargesheet for the case is so weak that the perpetrator gets away with a minimal sentence from the court.

The indifference of law enforcement agencies and the involvement of elected officials in crimes against people of the oppressed groups further fuel the impunity among the privileged groups. This is a common phenomenon in every oppressive system. Every time a white cop kills an unarmed person of color, White people justify the abuse against people of color. Every time a sexual predator walks free due to a lack of ’evidence,’ men gain confidence in physically violating woman, ignoring their boundaries. It is this impunity that makes sure that the oppressed group cannot rise from the dehumanization.

Casteism is ‘Dead’ in Nepal?

All forms of caste-based discrimination have been legally abolished for years. According to the law, it is illegal for a person to discriminate against anyone based on caste. The latest constitution of Nepal (released five years ago) even makes a provision to include at least one Dalit in every local political entity. These recent developments have many members of the privileged group consider casteism as an issue of the past. But that is the nature of privilege: it is invisible to the one benefitting from it.

But the caste system still has a stronghold in the Nepalese society. In fact, an elected political representative was beaten to death by two of her neighbors. Her crime: she touched the common water source. In a society where an elected representative (who holds more power than an average person of her community) could be beaten to death, what level of violence could be inflicted upon other members of her community?

Within the nine years since the law was passed against caste-based discrimination, a total of seventeen Dalits have died within the country, who probably would have been alive had they been a member of a “higher” caste.

Systemic casteism is rampant. It is evident in the power differential that is still present. A power differential that was borne out of historical oppression of one group of people over another. It is evident in the police administration’s refusal to register cases where the victims are Dalit. This makes it easier for perpetrators to target Dalit victims. It is evident in the basic civil rights that have been denied to Dalits. It shows that despite the laws banning it, the concept of pollution associated with one group of people is still strong, at least among ‘higher’-caste individuals.

The caste system is an oppressive system that benefits a certain group of people at the expense of another. A familiar pattern, in varying contexts, across the globe. Those who benefit have a strong motivation (and also the means) to keep this system alive. Dismantling the caste system, like any other oppressive system, is not easy, neither is humanizing a group of people that have so long been dehumanized.

A just society cannot be born as long as an oppressive system is in place.

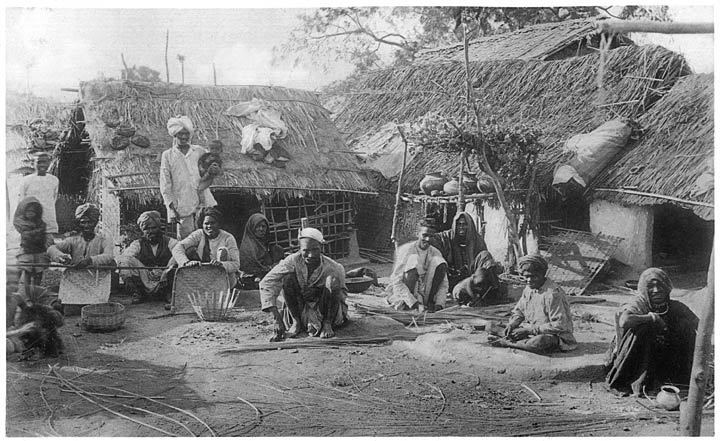

Salonika is an organizer at DGR South Asia and is based in Nepal. She believes that the needs of the natural world should trump the needs of the industrial civilization. Featured image: A member of a scheduled caste making baskets of bamboo. Source: The Tribes and Castes of Central Province of India by R. V. Russell