Editor’s Note: Today we’re sharing the following brief essays written by members of Deep Green Resistance:

- Why I Joined Deep Green Resistance

- A Culture of Resistance

- Why Should We Care About the Planet?

- How Do We Prepare For What’s Ahead?

- My Favorite Natural Place

My Favorite Natural Place

Photo: Iván Lada via Pexels

When I was about 8 I lived in the mountains and our home was surrounded by tall needly trees.

Not too far from one corner of the home, just slightly down the hill, was a small cluster of boulders. The rocks were situated in such a way that I could just manage to nestle myself 8-year-old self between them.

It was a tiny haven. A mini open-air dwelling and escape from regular life.

The chipmunks would occasionally join me and there we’d sit listening to the trees creaking in the wind.

I haven’t lived in the woods or any place even remotely as wild since. I’ve called cities home for the majority of my life, both before and after that time. And for an embarrassingly long time, I didn’t realize anything was missing from my life.

But somehow I finally realized the errors in my ways. There wasn’t any specific moment in time or place I visited that reminded of what I was missing. But I began to seek out natural refuges wherever I was. And when I took the time to look around me, I saw that beautiful places were everywhere. Not just in the mountains but in the city parks. And at the beach. On the trails near my home. Even my backyard.

If I had to pick just one favorite place in nature anywhere, I think the mountains will always top the list. But actually I like to think that wherever in nature I happen to be is my favorite place.

Why Should We Care About the Planet?

Photo: Tomáš Malík via Pexels

Two thirds of the oxygen in the air we breathe comes from plankton in the ocean. We evolved with nature, shaped by our relationships with the plants and animals around us.

Every cell in our bodies comes from nature. We are made of water, plant and animal, virus and microbe. The bacteria in our gut outnumber our own cells. We are human only in relationship with the more than human world. And it is an honour to be related. To share a connection with the magnificence and intelligence embodied in the diversity of species who are our kin. It is an honour to be an animal on this planet.

I care because I am in love with the natural world. And knowing what I know, I think it is a necessity to protect it. But more than that, it is an act of gratitude. The Earth gives us our very lives. It gives us the most beautiful things we will ever experience. I could work my whole life in activism and never repay the cost of a single breath of ocean air.

How Do We Prepare For What’s Ahead?

Photo: Johannes Plenio via Pexels

We are living in unpredictable times. Whether it’s the threat of nuclear annihilation, economic depression, or ecological collapse, no one can predict exactly what will happen or when. What we do know is that cities and suburbs will not be places humans can live in the long run.

Women need to learn self-defence now. As things become increasingly chaotic, men will look for an outlet for their violence. Those outlets are always women and nature. We can attempt to learn the skills that are necessary for survival in traditional human cultures.

But there are no personal solutions to social problems, which means we need to build communities, we need to organize, and we need to defend the natural world as if our lives depend on it, because they do.

A Culture of Resistance

Photo: Tim Gouw via Pexels

What does it mean to have a culture of resistance? What does this culture value? What is it resisting, and why? How is it different from the dominant culture?

The culture that we are living in now — a capitalist, industrial society — has certain values that we have been told are important for our well-being. Some of these values are: unlimited growth is good, we can have whatever we want, humans are superior to all other life forms on earth, we can tame the natural world for our own purposes, and the individual is more important than the community.

The problem with these values is that they are unjust and unsustainable. We aren’t living within the natural limits of our planet. We think we can continue to use up everything on the earth, and there will be no consequences. And if there is a problem, technology will solve it.

In the meantime, the population continues to rise, more and more of the earth is being destroyed, and more species are dying every day. People are becoming more alienated from each other. They don’t understand, or don’t want to acknowledge, that industrial civilization is the cause of all this suffering.

A culture of resistance rejects industrial, capitalist values. It fights for the natural world and knows that we are just one of many species that share this earth.

A culture of resistance joins together as a community, and rejects the idea of individualism. No one person is more important than another. We work together to meet our needs. We respect all beings and realize that we are dependent on nature to live. Nobody should be using up all the natural resources, thereby making it very difficult for others — human and nonhuman — to survive. It reminds me of the Buddhist teaching, “Do not take anything that is not freely given.”

A culture of resistance recognizes that the earth is finite. The planet can support a few million people, but not billions. It can provide us with all we need to stay alive and healthy: clean water and air, natural food, and adequate shelter. Other beings on the planet are respected and seen as part of the natural community, not things to be exploited. Hunter-gatherers used to live in harmony with nature for thousands of years, and it was sustainable.

The modern culture we live in today is toxic in so many ways. If we do not resist, it will continue to grow until it collapses under its own weight, causing unimaginable destruction and suffering. We must get rid of industrial civilization. Join the culture of resistance!

Why I Joined Deep Green Resistance

By Iona

Photo: Sofie Vanborm via Pexels

When I came across Deep Green Resistance I had no background in environmentalism and no knowledge about the ecological crises our planet was facing, and in many ways I felt like this put me at a disadvantage. But I think it gave me one really important advantage: it meant that I hadn’t yet been taken in by many of the false solutions offered by the mainstream environmental movement.

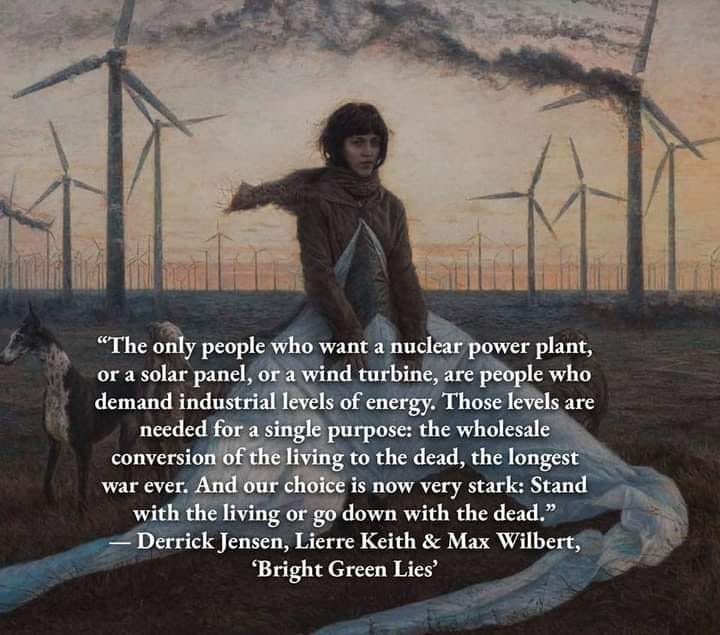

I hadn’t been primed to believe that my power as an activist was limited to petitions, street protests, reducing my carbon footprint and so on. And it meant that I didn’t already have a strong belief that technologies like wind and solar were solutions for the planet. It quickly became clear to me, through understanding this new analysis, that such technologies can only be seen as solutions in a world in which humans have lost their true connection to the natural world.

I learned that some studies have shown that renewables are expected to be the number one cause of habitat destruction in coming years. So that begs the question, is that what the planet needs? Is that something I can stand by and support?

My hope is that more people start to question some of these mainstream narratives, whether or not they already understand what’s happening to our planet — our home.

I want more people to look at the facts, and be unafraid in making up their own minds how they feel about what they see.

I want more people to feel confident in questioning whether a new form of industry that calls itself “green” is what the planet really needs, whether it’s really what we want to be doing to our home. And whether we think this industrial way of life we’ve all become so used to is really sustainable.

Good essays, though the fact that why we should care about the planet is even a sane question shows how messed up our entire attitudes and feelings are regarding the rest of the Earth.

I would add one more “essay,” though it’s neither brief nor an essay (it’s an outline for a book). I guess one could call it How to Fix the Ecological and Environmental Problems Caused by Humans. https://rewilding.org/fixing-humans-by-expanding-our-consciousness/

It is the confession of a failed species that we should even feel the need to explain how we came to appreciate nature. It’s like explaining why we appreciate being able to breathe, or the fact that we aren’t starving.

Too many of us — the vast majority of us — breathe and have food only because we have taken those treasures from the billions of other lives that existed, before we destroyed their homes to build our farms, created our cities, and began to depend on non-renewable resources, to live as we do.

Why does no other species feel the need for electricity, paved roads, motor vehicles, airlines, factories, landfills, sewage plants, etc? And how do we who “require” such things justify our existence?

Just in the lifetimes of the personal relations I have known in my 75 years, such things as automobiles, airplanes, the power grid, and indoor plumbing have come into existence, and come to be regarded as “necessities,” and as “the norm.”

As I’ve said here before, the grandmother I grew up with lacked hot water in her home until after I started school. She never drove a car, boarded an airplane, owned a television, or left the state of her birth. And yet, somehow, she never missed or wanted any of those things.

As for how we got to the world and predicament we are in today, however, I need only look back a generation or two — to a father who was one of ten children, and a great-grandfather who was one of nine. Until recently, we have bred like rats. And on most of the world’s continents, many still do.

Just last night, I watched a documentary about a fertility clinic in China, and heard a women selfishly lament that, “We must reproduce. Infertile women are laughed at.”

Of all the facts and statistics I have learned and been shocked by since discovering DGR, perhaps the most shocking are these: Since 1900, human population has grown by 500%. Worldwide consumption of raw materials has shifted from two-thirds renewable to two-thirds NON-renewable. Total consumption has increased by 1000%, and per capita consumption by more than 400%.

And yet, the number of starving has increased astonishingly. The number of migrants forcing their way into North America, Europe, and Australia is now into the millions per year, and is expected to increase exponentially, by the middle of the century.

In short, industrial man (that’s us) has become a species of thieves, rapists, murderers, and suicidal maniacs, obsessed with forever having more — more people taking more from everyone else, and killing and destroying more land, air, water, plants, and animals in the process.

My environmentalism began with a childhood realization that we, in the industrial world, were fanatically using things that were finite, that any use of non-renewables is unsustainable, that our leaders knew but didn’t care, and that the rest of us mostly just went along — because we’re either too greedy or too stupid to change. And I went along with the crowd, not realizing that I was living a life of crime, or that humanity as a whole could live morally and sustainably.

And it isn’t just a matter of the “haves” exploiting the “‘have-nots.” The record is pretty clear that most of the “have-nots” want to become “haves,” too, and want to get there as fast as possible.

By simple arithmetic, it’s easy to see that we have forfeited our right to exist. If that only meant the death of industrial humanity, I’d welcome it — even though the people I love and I would die, too.

The great crime is that we’re taking a couple of million innocent species down with us, and that the extinct can never return to the world we’re killing, and much of the poison we’re leaving behind.

Over the past 25 years, I’ve made some minor concessions. I’ve stopped eating four-legged animals, refused to board another airliner, and moved into a 250 square foot home, with no hot water, and no appliances other than a toaster oven, one hot plate, a small refrigerator, a TV, a radio, a laptop computer, an 800-watt space heater, and a small car I drive leas than 2000 miles a year.

In other words, I continue to live a lifestyle of luxury and excess unavailable to anyone, four generations ago; unimaginable to kings, two centuries ago; and probably impossible for anyone, by the end of this century.

We are using up the only life-supporting planet we know of. And our mindless culture of perpetual growth seems determined to see that no one will survive our crimes.

Hello again, Jeff and Mark! Good to read your thoughts.♥

And Mark, so different from Bono’s rose-tinted TED talk about the alleged good news about poverty in Africa.

A couple of thoughts on population and human overshoot. When you’re living as a normal animal in the food web of a healthy ecosystem, the numbers of your particular species are automatically kept in balance by the food web itself turning species reproductive excesses into food for other species (via predation, accidents, illness).

Species with higher investment into rearing their offspring have proportionally fewer offspring, e.g. ungulates can have a maximum of one a year, while a housefly can have thousands a year. Even the one a year is more than it takes to replace parents who live multiple years, but reproductive excess in an intact ecosystem is the main driver for evolution, adaptation and speciation, as well as the main provider of food for the biotic community. All the amazing diversity of life forms in nature is only possible because of these core processes.

Many Indigenous cultures had low and relatively steady population numbers, and participated in actively preventing excess numbers with forms of contraception, abortion and, if push came to shove, infanticide – there were only so many that could be supported in the community. The existence of infanticide in places like Tahiti caused much hand-wringing and moral-high-horse-riding by the religious missionaries that came with colonisation.

Somewhere along the line, expansionist biosphere-destroying cultures had decided breeding in large numbers was a good thing – more soldiers to take resources from other cultures, more slaves to do the work, more heirs to inherit empire. Our Western culture has its roots in exactly that, and in the religious exhortation to “multiply, and subdue the earth”.

Which explains the culture around the time of Mark’s grandfather’s time, and all the cultural conditioning about the virtues of raising many offspring – which even in my own generation (one behind Mark) was an enormous pressure: People with few or no children were “selfish” and apparently freeloading off other people’s children (although those are total misconceptions, not that being a misconception has ever stopped something being paraded as a fact).

Social democracies such as found in Scandinavia don’t have that level of rhetoric and freely allow people to limit their family sizes; expansionist countries attempt to enforce population growth, both at home and in the countries they wish to exploit – as evidenced by US reproductive policies both at home (including the current assault on abortion and contraception) and abroad (people in Third World countries often want far smaller families than they actually end up having, because they don’t have effective access to family planning services).

I have compassion for the Chinese woman in the fertility clinic, and the social pressures and devaluation as an individual she is likely to have experienced, to have led to her observation that infertile women are laughed at and therefore she is trying to have a child. I wish we could offer her an alternative culture where a wish for a small family or none at all given our nightmare scenario would be supported, and where women’s attempts to access contraception and abortion were honoured, instead of met with oppression and social coercion. My husband and I were outliers from the start and were able to shrug off the rhetoric, but not without being seen as pariahs by some respected members of the community – which is how this commonly goes.

DGR is an alternative culture and supports those things. Knowing firsthand what it’s like to be a woman in Western society, I’m very happy to see the centrality of ecofeminism to its philosophies as a group.♥

Hello Iona and thanks for sharing ♥ from another recent addition to DGR. That’s an interesting perspective you have, going straight to deep green without being caught up in bright green first. It really is so obvious once we cut through the dominant narrative.

Doing that without social support can be an isolating and disconcerting experience, very much as is experienced by survivors of trauma in dysfunctional families, which is a similar process to coming to question the dysfunctional culture we live in. The elephants in the room, the conspiracies of silence, the false narratives, the gaslighting etc etc, are very similar, as is the sad and vastly complicating fact that we start out depending on our dysfunctional family and our dysfunctional anthropocentric culture for our own survival (and disentanglement from the culture is very challenging).

Reading your words got me thinking back to my own journey with environmentalism. When I was 16 I knew from personal observation and also from reading other people’s accounts that what we were doing to the Earth and our kin species on it was abhorrent. In the late 70s I had been fortunate to attend a comparatively enlightened primary school whose library stocked many books on nature and indigenous cultures and also encouraged us to subscribe to an ecological magazine for German primary school children that highlighted issues like habitat destruction, wildlife extinction, pollution and industrial animal farming while offering articles by biologists on life in the Serengeti, insect life in the average suburban backyard, etc.

I had a relatively nature-immersed, free-range childhood that included school holidays spent roaming comparatively unscathed nature in the Italian Alps. At the start of my high school years we moved to Australia, where I saw firsthand the effect of a skyrocketing human population on remnant ecosystems that were cleared far and wide for suburbia, agriculture and industry. All the places close at hand in which I used to admire wildlife and incredible botanical diversity as a middle schooler were bulldozed or otherwise degraded out of existence. It broke my heart.

So when my high school biology teacher asked 16-year-old me if I wanted to apply for an Environmental Science scholarship, I naively thought this would be a way to help turn things around. However, I soon realised that most of the academic programme I landed in was beholden to ALCOA and other local industries and developers. Environmental management projects students participated in were farcical and treated the Earth as an object for our consumption. The most valuable course I did was an elective called Environmental Ethics, run out of the School of Arts. It was taught by an environmental philosopher and eco-feminist who introduced us to the deep ecology movement and to philosophies that finally chimed with my own heart. I additionally completed a Biology degree just so I could learn more about the natural world.

After graduation I spent just long enough working professionally in the field, in an ostensibly non-greenwash role, to realise that the reports and advice of concerned biologists were routinely ignored and had been forever – the commissioning of ecological advice is basically a box-ticking exercise for bureaucrats so they can say they have spent $$$ consulting biologists. It’s worth about as much as “dermatologically tested” on a tub of skin cream – it’s a marketing exercise. I then spent nearly two decades in education, which I’ve never regretted, before my husband and I bought a rural block with 50 hectares of remnant ecosystem, where we now live off-grid, conserving as citizens what I could never conserve as a professional.

Since we had to build a dwelling to live here, we owner-built a water and nutrient recycling earthship type house which has minimal ongoing energy inputs for its operation – four camping bottles of gas a year for cooking, still dwarfed by the unfortunate necessity of one of us having to commute to an office job in a very small car to be able to finance the mortgage we took on to protect the remnant bushland, plus rates, compulsory insurance, running costs of the small car, and whatever materials and additional food we currently need for our own survival; as well as the fencing and seedlings required for hand planting of shelter belts, wildlife corridors and permaculture on the previously cleared 12 hectare area of the block which we run as a smallholding and from which, at present, after a decade of practice and with just one person to look after that side and no fossil fuels or large machinery, we can grow about 50% of our own food (and sell a modest amount of organically grown grass-fed free-range beef with which to feed others and hopefully do our part in reducing the ongoing market pressure for clearing yet more remnant ecosystems for livestock grazing).

We are off-grid and have a small solar-electric system to run chiefly lights, computers, and the freezers which currently help us feed ourselves. While we use a modest fraction of the electricity of the average Australian household, it’s still more than my own grandparents used, and in essence I’ve come to view it as a weaning exercise to buy us a few decades to learn to do without – for which, I have realised, we would need a small community here working together. But then, we also don’t expect to survive major civil unrest and the inevitable bullies with guns, not on our own, so the main reason we’re here is to defend for as long as we can the 50 hectares of remnant bushland on the block, with the legal title purchased from our dysfunctional culture and with our own selves, to allow it and its biota to go on living for as long as possible.

It took us a decade to be able to come up for air after throwing ourselves into this back-to-the-land project, and then, last year, I discovered DGR and breathed a sigh of relief, not for the future of the biosphere but for the small island of sanity it represents, and the kindred spirits from all over the world that I am now meeting, through books and online connection, from our own remote corner of the world. ♥

Best wishes to all of you and much appreciation for everything any of you are doing and learning to do, to help reduce your footprints, actively defend other biota, and form community with other biophilic people. ♥♥♥