by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 30, 2016 | Male Violence

Featured image: Counting Dead Women project

by Karen Ingala Smith / openDemocracy

Across everything that divides societies, we share in common that men’s violence against women is normalised, tolerated, justified – and hidden in plain sight.

Since 25 November last year, at least 118 women and girls in the UK aged over 13 have been killed by men, or a man has been the primary suspect.

An average of one woman dead at the hands of a man every 3 days.

I’ve been recording women’s names and details of how they were killed since January 2012 when Counting Dead Women was launched.

Today we commemorate 653 women.

Men’s fatal violence against women in the UK crosses boundaries of class, race, nationality and age. Over the last year, the oldest woman killed was 85, 18 were over 60, and 21 were aged 25 and under. They included hairdressers, writers, shop assistants, prostituted women, a politician, lawyers, students and school girls; women born in Eritrea, Poland, China, Italy and other countries, and of course women born in the UK with a range of ethnic backgrounds. Most, but not all, were killed by current or former partners, others were killed by burglars, rapists, neighbours, brothers, sons, men they saw as friends or men who paid for sex.

Many think of intimate partner violence, or, more broadly, domestic violence, if they think about women killed by men at all. This focus is reflected and reinforced by official statistics. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publishes an annual report on violent crime, including homicide. For the year ending March 2015, the Home Office Homicide Index recorded 518 homicides. There were 186 female victims, 331 male victims, and one victim whose sex is unknown/undeclared.

The proportion of female victims was the highest recorded for 20 years. 19 men and 81 women were killed in circumstances described as partner/ex-partner homicides. 31 were killed by other family members (domestic/family violence).

But what about the remaining 74 women? Is it important to have a sex-specific analysis of their deaths?

51-year-old Majella Lynch died in hospital after the a removal of a 400ml shampoo bottle from her abdominal cavity. William Mousley QC, prosecuting, said “The bottle could not have been self-inserted because of the extreme pain such an act would have caused.” Mousley said her attacker, Daniel McBride, 43, an habitual user of hardcore pornography “had an interest in violent sexual activity and was in the mood for sex that night having had an argument with his girlfriend and being rejected by another female.” Yvette Hallsworth, 36, was selected by Mateusz Kosecki because she was “slightly built.” At 18 he was already a predator targeting women in prostitution. He had attacked at least three women who sold sex before he killed Yvette Hallsworth, stabbing her 18 times. Judge Michael Stokes QC described him has having a “fascination, if not an obsession” with prostituted women.

How can a feminist perspective of men’s violence against women disregard some women when patriarchal misogyny, violent sexualisation and objectification are so clear in their murders?

The prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is globally uneven. Corradi and Stockl, 2014, looked at the relationship between men’s fatal violence against women, feminist activism and government policy in European countries since the 1970s. They found no clear link between rates of IPV and government policies, rather that feminist activism was a crucial catalyst of change – and was most effective when it was independent of government.

“Since the late 1960s, organized women’s activism played a fundamental role in rallying the state to tackle VAW.” (Corradi & Stockl, 2014: 605).

It is estimated that across the world around 66,000 women and girls are violently killed every year. Comparing country-by-country data is challenging, partly because there isn’t a cross-national approach to collecting and disaggregating murder statistics by the sex of both victim and killer, but globally women are at greater risk than men of intimate-partner homicides and are overwhelmingly killed by males. Across everything that divides societies, we share in common that men’s violence against women is normalised, tolerated, justified – and hidden in plain sight, and that there is a lack of truly proactive and deeply rooted state action to protect women’s right to life.

Of course it is essential to look at domestic and intimate partner violence, including homicide; but to focus only on this context not only obscures the full extent of men’s fatal violence against women, it also misses the sex differences within these crimes. In the UK, women are more than 7 times more likely to be killed by a man than men are by a women in the context of intimate partner homicide. Men are more likely than women to be killed by a same-sex partner, and histories of violence before the homicide are different – with men tending to have inflicted months or years of violence and abuse on the women they go on to kill, while women tend to have suffered months or years of violence and abuse from the man they go on to kill.

Responses to men’s violence against women which focus almost exclusively on “healthy relationships,” supporting victim-survivors and reforming the criminal justice system simply do not go far enough. Men’s violence against women is a cause and consequence of sex inequality between women and men. The objectification of women, the sex trade, socially constructed gender, unequal pay, unequal distribution of caring responsibility are all simultaneously symptomatic of structural inequality whilst maintaining a conducive context for men’s violence against women. Feminists know this and have been telling us for decades.

One of feminism’s important achievements is getting men’s violence against women into the mainstream and onto policy agendas. One of the threats to these achievements is that those with power take the concepts, and under the auspices of dealing with the problem shake some of the most basic elements of feminist understanding right out of them. State initiatives which are not nested within policies on equality between women and men will fail to reduce men’s violence against women. Failing to even name the agent – men’s use of violence – is failure at the first hurdle.

Working in partnership, Counting Dead Women and Women’s Aid Federation England, supported by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and Deloitte, have developed The Femicide Census, a relativity database that allows data to be collated and disaggregated for analysis. It currently contains information regarding over 1000 women who were killed by men between 2009 and 2015. Our intention is to build a research resource than can be used as a tool to influence understanding and policy development. We’ll soon be releasing our first report. In September, our work was cited as an example of good practice in a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women.

Feminists have started Counting Dead Women or femicide count projects in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Counting Dead Aboriginal Women. There is feminist action against femicide on every continent, in countries including Argentina, Peru, Italy, Spain, India.

Women across the world are finding ways to protest the murders of our sisters.

By recording women’s names, and where possible their photographs, we want to create a reminder that women are not reducible to statistics.

653 women dead in the UK in 5 years at the hands of men cannot be 653 isolated incidents. Action is needed and action can be taken to reduce these killings.

Read more articles on openDemocracy in this year’s 16 Days: Activism Against Gender-Based Violence. Commissioning Editor: Liz Kelly

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 29, 2016 | Rape Culture, Repression at Home

by Robert Jensen

From a “critique” of my work on the latest Professor Watchlist, I learned that I’m a threat to my students for contending that we won’t end men’s violence against women “if we do not address the toxic notions about masculinity in patriarchy … rooted in control, conquest, aggression.”

That quote is the “evidence” that I am one of those college professors “who discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values, and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom,” according to the watchlist’s mission statement.

This rather thin accusation appears to flow from my published work instead of an evaluation of my teaching, which confuses a teacher’s role in public with the classroom. So, I’ll help out the watchlist and describe how I address these issues at the University of Texas at Austin, where I’m finishing my 25th year of teaching. Readers can judge the threat level for themselves.

I just completed a unit on the feminist critique of the contemporary pornography industry in my course “Freedom: Philosophy, History, Law.” We began the semester with On Liberty by John Stuart Mill (I’ll assume the Professor Watchlist approves of that classic book), examining how various philosophers have conceptualized freedom. We then studied how the term has been defined and deployed politically throughout U.S. history, ending with questions about how living in a society saturated with sexually explicit material affects our understanding of freedom. I provided context about feminist intellectual and political projects of the past half-century, including the feminist critique of men’s violence and of mass media’s role in the sexual abuse and exploitation of women in a society based on institutionalized male dominance (that is, patriarchy).

The revelations about Donald Trump’s sexual behavior during the campaign provided a “teachable moment” that I didn’t think should be ignored. I began that particular lecture, a week after the election, by emphasizing that my job was not to tell students how to act in the world but to help them understand the world in which they make choices.

Toward that goal, I pointed out that we have a president-elect who has bragged about being sexually aggressive and treating women like sexual objects, and that several women have testified about behavior that—depending on one’s evaluation of the evidence—could constitute sexual assault. Does is seem fair, I asked the class, to describe him as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

Trump sometimes responded by contending that Bill Clinton was even worse. Citing someone else’s bad behavior to avoid accountability is a weak defense (most people learn that as children), and of course Trump wasn’t running against Bill, but we can learn from examining the claim.

As president, Bill Clinton abused his authority by having sex with a younger woman who was first an intern and then a junior employee. He settled a sexual harassment lawsuit out of court, and he has been accused of rape. Does it seem fair to describe Bill Clinton as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

So, we live in a world in which a former president, a Democrat, has been a sexual predator, yet he continues to be treated as a respected statesman and philanthropist. Our next president, a Republican, was elected with the nearly universal understanding that he has been a sexual predator. How can we make sense of this? A feminist critique of toxic conceptions of masculinity and men’s sexual exploitation of women in patriarchy seems like a good place to start.

In that class, I spent considerable time reminding students that I didn’t expect them all to come to the same conclusions but that they all should consider relevant arguments in forming judgments. I repeated often my favorite phrase in teaching: “Reasonable people can disagree.” Student reactions to this unit of the class varied, but no one suggested that the feminist critique offered nothing of value in understanding our society.

Is presenting a feminist framework to analyze a violent and pornographic culture politicizing the classroom, as the watchlist implies? If that’s the case, then the decision not to present a feminist framework also politicizes the classroom, in a different direction. The question isn’t whether professors will make such choices—that’s inevitable, given the nature of university teaching—but how we defend our intellectual work (with evidence and reasoned argument, I hope) and how we present the material to students (encouraging critical reflection).

If the folks who compiled the watchlist had presented any evidence that I was teaching irresponsibly, I would take the challenge seriously. At least in my case, the watchlist didn’t. But rather than assign a failing grade, I’ll be charitable and give the project an incomplete, with an opportunity to turn in better work in the future.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men, to be published in January by Spinifex Press. Other articles are online at http://robertwjensen.org/. He can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 25, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

by Survival International

A mining company in India has renewed its efforts to start mining on the sacred hills of the Dongria Kondh people, despite previous defeat in the Supreme Court, and determined opposition by the tribe.

The Dongria Kondh consider the Niyamgiri Hills to be sacred and have been dependent on and managed them for millennia. Despite this the Odisha Mining Corporation (OMC), which previously partnered with British-owned Vedanta Resources, is once again attempting to open a bauxite mine there.

In February this year, OMC sought permission from India’s Supreme court to re-run a ground breaking referendum, in which the Dongria tribe had resolutely rejected large-scale mining in their hills. This petition was thrown out by the Supreme Court in May.

India’s Business Standard reported recently that OMC is gearing up for yet another attempt to mine, after getting the go-ahead from the government of Odisha state.

Dongria leader Lodu Sikaka has said: ”We would rather sacrifice our lives for Mother Earth, we shall not let her down. Let the government, businessmen, and the company argue and repress us as much as they can, we are not going to leave Niyamgiri, our Mother Earth. Niyamgiri, Niyam Raja, is our god, our Mother Earth. We are her children.”

For tribal peoples like the Dongria, land is life. It fulfills all their material and spiritual needs. Land provides food, housing and clothing. It’s also the foundation of tribal peoples’ identity and sense of belonging.

The theft of tribal land destroys self-sufficient peoples and their diverse ways of life. It causes disease, destitution and suicide.

The Dongria’s rejection of mining at 12 village meetings in 2013, led the Indian government to refuse the necessary clearances to mining giant Vedanta Resources. This was viewed as a heroic David and Goliath victory over London-listed Vedanta and the state-run OMC.

Only the Dongria’s courageous defence of their sacred hills has stopped a mine which would have devastated the area: more evidence that tribal peoples are better at looking after their environment than anyone else. They are the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world. Protecting their territory is an effective barrier against deforestation and other forms of environmental degradation.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 21, 2016 | Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home

by Indigenous Environmental Network

Cannon Ball – On November 20th at approximately 6PM CST over 100 Water Protectors from the Oceti Sakowin and Sacred Stone Camps mobilized to a nearby bridge to remove a barricade that was built by the Morton County Sheriff’s Department and the State of North Dakota. This barricade, built after law enforcement raided the 1851 treaty camp, not only restricts North Dakota residents from using the 1806 freely but also puts the community of Cannon Ball, the camps, and the Standing Rock Tribe at risk as emergency services are unable to use that highway.

Water Protectors used a semi-truck to remove two burnt military trucks from the road and were successful at removing one truck from the bridge before police began to attack Water Protectors with tear gas, water canons, mace, rubber bullets, and sound cannons.

At 1:30am CST the Indigenous Rising Media team acquired an update from the Oceti Sakowin Medic team that nearly 200 people were injured, 12 people were hospitalized for head injuries, and one elder went into cardiac arrest at the front lines. At this time, law enforcement was still firing rubber bullets and the water cannon at Water Protectors. About 500 Water protectors gathered at the peak of the non-violent direct action.

The following is a statement from the Indigenous Environmental Network:

“The North Dakota law enforcement are cowards. Those who are hired to protect citizens attacked peaceful water protectors with water cannons in freezing temperatures and targeted their weapons at people’s faces and heads.

“The Morton County Sheriff’s Department, the North Dakota State Patrol, and the Governor of North Dakota are committing crimes against humanity. They are accomplices with the Dakota Access Pipeline LLC and its parent company Energy Transfer Partners in a conspiracy to protect the corporation’s illegal activities.

“Anyone investing and bankrolling these companies are accomplices. If President Obama does nothing to stop this inhumane treatment of this country’s original inhabitants, he will become an accomplice. And there is no doubt that President Elect Donald Trump is already an accomplice as he is invested in DAPL”.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 18, 2016 | Alienation & Mental Health, Listening to the Land

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

This first appeared on Jason Howell’s Howlarium. Special thanks to Jason for his graphics.

From Jason: “Where it’s not uncommon for contemporary writers to root their work in mining—lived experience, the depth of the canon, the cultural moment, whatever—Will Falk, poet, lawyer, and environmental activist from Park City, Utah, makes the whole of his work about listening to the natural world. The effect, in this reader’s opinion, is a kind of anthropocentric-for-biocentric blood transfusion.

“I asked Will to describe what it took for him to get enough media and concrete out of the way so as to hear from the biosphere loud-and-clearly. As fate would have it, he and his partner were gearing up for a camping trip in southern Utah, so he’d have some space to think about it. Here’s what he came back with.”

Survival compels me.

My own survival, the survival of those I love, and the survival of the biosphere compel me. Listening to the land saves my life.

An old, gray seagull flying wobbly through thick, wet snow to speak to me from the concrete ledge of a window I watched Lake Michigan from while I recovered from a suicide attempt in St. Francis Hospital in Milwaukee, WI saved my life. A pregnant mother moose, who shared our single-track 17-mile snowmobile trail at the Unist’ot’en Camp turned to stare me in the eye giving me a glimpse into the wisdom of the wild, saved my life. The wind whispering questions through aspen leaves in Park City, Utah pulled me from my depressed mind a few weeks ago and, again, saved my life.

The compulsion will last as long as my survival. My survival will last as long as the compulsion. I suffer from major depressive disorder and general anxiety disorder caused by the same forces producing total ecological collapse. I must listen to the biosphere to resist depression and humans must listen to the biosphere to stop the destruction of Life.

A novice attorney, I wanted to die. I was so tired.

Before I was a writer, I was a public defender in Kenosha, WI doing my best to push back against a criminal justice system intent on perpetuating institutional racism. I spent all my time rotating between the wooden walls of the courthouse, the glass walls of the office, and the steel walls of the jail.

A novice attorney, I was determined not to let my inexperience affect my clients, but I made mistakes. The only solution I could come up with involved working more urgently and working longer hours. I woke up at 3AM to review my case files. I worked Saturdays and Sundays. I walked back to my beat Jeep Cherokee in the parking lot of the Kenosha County Jail after telling another client there wasn’t much I could do for her, and broke down sobbing with my forehead against the steering wheel in broad daylight. I became exhausted. I made more mistakes.

One night, I came home from dinner and took all the Ambien sleeping pills I had just been prescribed that morning. I wanted to die. I was so tired.

I was also living a life completely mediated by humans. This mediation was total. Physically, my life happened almost completely within atmospheres created by humans: the office, the jail, the courthouse, my apartment building. Spiritually, I had forsaken the Catholicism I was raised in, but instead of recognizing the sacred in every living being around me, my development into a mature member of a natural community stalled in an adolescent insistence that life had no meaning outside the meaning humans could create.

This insistence imprisoned me psychologically as surely as the jail physically imprisoned my clients. I became Sisyphus pushing my boulder up the hill, blind to the countless non-human others producing my life and cut off from natural allies in the biosphere.

As the pills entered my bloodstream and I settled into what I thought was my deathbed, time froze on my consciousness. I’m not sure I believe in a spiritual afterlife, but this last moment before I passed out was a functional eternity. I was confronted with the totality of my life and I realized that if I died this night, I would have failed my role. And, if the pain that was branded onto my mind with my recognition that I could give so much more to Life was the last experience frozen on my consciousness forever, then hell is very real, indeed.

A heavy snow began to fall.

After this suicide attempt, I spent a week in the psyche ward of St. Francis Hospital in Milwaukee. The St. Francis psyche ward was on the seventh floor of an eight-floor building. For exercise, and because there was nothing else to do, I braved the fluorescent lights outside my room and paced the long hallway that made up most of the seventh floor.

At each end of the hallway were wide windows. One looked west into the rows of old company housing for the Milwaukee Iron Company. The other looked east over the waters of Lake Michigan. Patients are not allowed off the seventh floor and there were rusty iron bars outside the glass just in case we were tempted to take that route to fresh air. I tried to open a window facing Lake Michigan anyway. It would not open. A heavy snow began to fall surrounding the hospital in more white. I pressed my forehead against the cold glass pane. The cold felt good.

It was not long before I saw an old spotted seagull awkwardly wheeling and diving through the falling snow. I was mesmerized by the odd gracefulness in his seemingly drunken turns through the snow. His circles brought him closer and closer to my window. I wondered why he was flying through such treacherous conditions. He was, of course, the only bird in the sky. As he flew closer, I was stricken with the beauty of his grayness against the white.

Gray. Color. A contrast to the blankness. I began to believe the drunk old gull was braving the snowstorm to speak to me. He passed a few feet from my window, dipped a wing, and wobbled back toward Lake Michigan. A few moments later he was back. He squeezed through iron bars over my window, faced me, made eye contact, and flew away.

The waves on the lake rippled gray, too. The heavy snow fell slowly, gingerly over the waters. The waves hesitated, hanging a moment in the air, before being swallowed by the lake. White became gray. I drank up the color for hours following one gray wave after another from their birthplace on the horizon until they washed not far below me onto the shore.

I was compelled to write this down. I’ve been watching and listening ever since.

Writing only for myself is masturbatory.

Depression is a chronic illness. Doctors know now that our biological stress response is largely responsible for depression. A body experiencing too much stress, for too long can overproduce stress response hormones. If these hormones are present for a long enough time they literally damage the brain. Depression results from this brain damage. The dominant culture (which I call “civilization”), based on ecological drawdown and enforced scarcity, creates profoundly stressful lives for its members.

Depression bends my mind over itself and makes listening a constant struggle. A classic depression symptom is social withdrawal and isolation. The brain reacts to depression in a similar way to other illnesses. When you get the flu, your body tells you to isolate. The same instinct is triggered with depression.

With the flu, the instinct is adaptive and good for the way it prevents contagion. But with depression the instinct can prove deadly. Isolation leads to rumination and rumination perpetuates the release of the very stress hormones that damage the brain and produce depression. In this way, withdrawal creates a vicious cycle and the cycle must be interrupted. Personally, I experience suicidal ideation too frequently making interruption of this cycle imperative for my personal survival.

Doctors strenuously encourage depressed patients to socialize even when every instinct tells them not to. Spending time with loved ones releases hormones that counteract stress hormones. Socializing also occupies the depressed mind so it cannot ruminate. When doctors insist that their patients spend time with loved ones, however, most people understand this to mean exclusively human loved ones.

That ancient seagull opened me to the vast possibilities for relationship in the natural world. The impulse to write about my experience with the seagull pulled me out of my depressed mind and gave me something to ponder beyond my own pain. I do not typically understand what non-humans are saying right away. Pinyon pine trees do not have tongues, the wind is too vast and too busy for words, and great blue herons do not speak English.

So, I have to ponder the experience. Life speaks in patterns, gestures, and themes that must be teased out. We understand through story and it is no wonder that we discover Life’s meaning in the act of telling stories. I feel that writing only for myself is masturbatory. It might feel good, but it doesn’t help anyone but me. Writing with the desire to share my experience publicly forces me to order my experience in such a way that it makes sense to other humans. In this way, writing becomes social on multiple levels. I listen to non-humans and then I begin public conversations with humans about what I think I’ve heard.

Listening to the biosphere goes well beyond my own survival.

The dominant culture exhibits many of the classic symptoms of depression as well. This culture has isolated itself from the biosphere and is suicidal—stepping ever closer to the brink of total ecological collapse.

This collapse, this suicidality, is produced, in part, by the dominant culture’s belief that humans are the only beings capable of speaking, the only beings worth listening to, the only beings capable of relating with. My friend, the brilliant environmental writer, Derrick Jensen, has given us a name for this phenomenon. He calls it “human supremacy,” and the myth of human supremacy is a foundational story the dominant culture is built upon.

Human supremacy is propagated by the dominant culture because it derives its power from ecological destruction. Before you can destroy non-human others you must silence them. Deep ecologist Neil Evernden has pointed out that the first thing scientists do in vivisection labs is cut the vocal cords of the animals they are going to operate on. The dominant culture cuts the vocal cords of non-humans, of people of color, of women, of anyone it wants to dominate.

I ignored non-human voices for too long and I almost destroyed myself as a result. The dominant culture ignores and actively suppresses non-human voices and is destroying Life as a result. I am not naive enough to believe that writing alone will stop the murder of the biosphere, but writing helps me understand non-human voices, helps me resist the seductions of depression in the process, and is a tool to remind humans of their heritage. I always seek to contribute my writing to serious, organized resistance. I believe my role in this resistance is to combat human supremacy through reminding my readers of the countless, beautiful voices—human and non-human—to listen to in the biosphere.

I am in love with aspen trees, with pinyon-juniper forests, with my one-year old nephew, with my four-year old niece, with their aunt (my amazing partner), with a rainbow trout that tickled my feet in a pool I soaked them in after a 50 mile hike in the Sierras a few summers ago, with that seagull that woke me up to it all. I am in love, so I listen, and when I listen I hear murmurs of fear about ever-growing threats. When you’re in love, you act to protect your beloved. We cannot fail to stop the dominant culture, because if we fail every voice will be silenced forever.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling

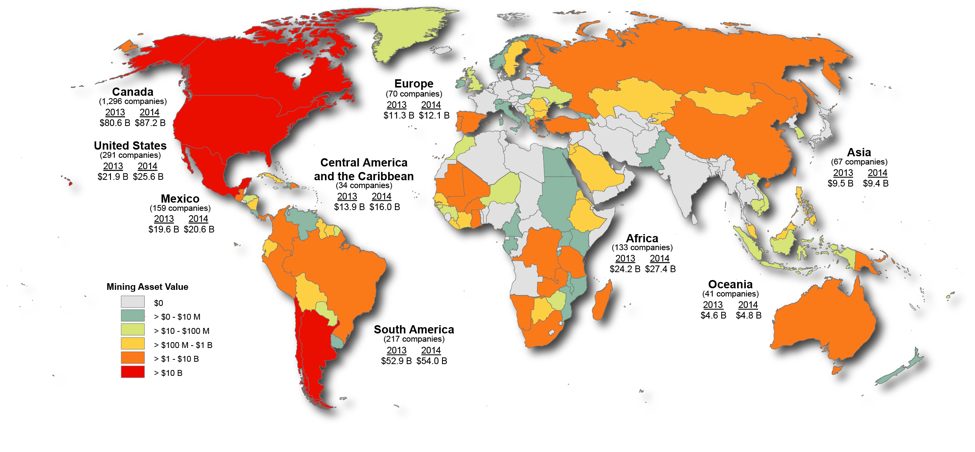

by Jen Moore / Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

Stories of bloody, degrading violence associated with Canadian mining operations abroad sporadically land on Canadian news pages. HudBay Minerals, Goldcorp, Barrick Gold, Nevsun and Tahoe Resources are some of the bigger corporate names associated with this activity. Sometimes our attention is held for a moment, sometimes at a stretch. It usually depends on what solidarity networks and under-resourced support groups can sustain in their attempts to raise the issues and amplify the voices of those affected by one of Canada’s most globalized industries. But even they only tell us part of the story, as Todd Gordon and Jeffery Webber make painfully clear in their new book, The Blood of Extraction: Canadian Imperialism in Latin America (Fernwood Publishing, November 2016).

“Rather than a series of isolated incidents carried out by a few bad apples,” they write, “the extraordinary violence and social injustice accompanying the activities of Canadian capital in Latin America are systemic features of Canadian imperialism in the twenty-first century.” While not completely focused on mining, The Blood of Extraction examines a considerable range of mining conflicts in Central America and the northern Andes. Together with a careful review of government documents obtained under access to information requests, Gorden and Webber manage to provide a clear account of Canadian foreign policy at work to “ensure the expansion and protection of Canadian capital at the expense of local populations.”

Fortunately, the book is careful, as it must be in a region rich with creative community resistance and social movement organizing, not to present people as mere victims. Rather, by providing important context to the political economy in each country studied, and illustrating the truly vigorous social organization that this destructive development model has awoken, the authors are able to demonstrate the “dialectic of expansion and resistance.” With care, they also show how Canadian tactics become differentiated to capitalize on relations with governing regimes considered friendly to Canadian interests or to try to contain changes taking place in countries where the model of “militarized neoliberalism” is in dispute.

The spectacular expansion of “Canadian interests” in Latin America

We are frequently told Canadian mining investment is necessary to improve living standards in other countries. Gordon and Webber take a moment to spell out which “Canadian interests” are really at stake in Latin America—the principal region for Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) in the mining sector—and what it has looked like for at least two decades: “liberalization of capital flows, the rewriting of natural resource and financial sector rules, the privatization of public assets, and so on.”

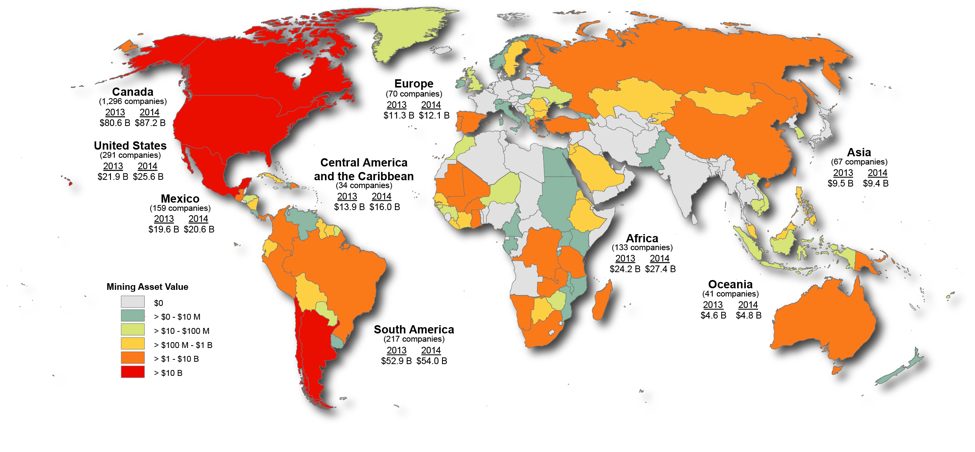

Cumulative CDIA in the region jumped from $2.58 billion in stock in 1990 to $59.4 billion in 2013. These numbers are considerably underestimated, the authors note, since they do not include Canadian capital routed through tax havens. In comparison, U.S. direct investment in the region increased proportionately about a quarter as much over the same period. Despite having an economy one-tenth the size of the U.S., Canadian investment in Latin America and the Caribbean is about a quarter the value of U.S. investment, and most of it is in mining and banking.

Canadian mining investment abroad

To cite a few of the statistics from Gordon and Webber’s book, Latin America and the Caribbean now account for over half of Canadian mining assets abroad (worth $72.4 billion in 2014). Whereas Canadian companies operated two mines in the region in 1990, as of 2012 there were 80, with 48 more in stages of advanced development. In 2014, Northern Miner claimed that 62% of all producing mines in the region were owned by a company headquartered in Canada. This does not take into consideration that 90% of the mining companies listed on Canadian stock exchanges do not actually operate any mine, but rather focus their efforts on speculating on possible mineral finds. This means that, even if a mine is eventually controlled by another source of private capital, Canadian companies are very frequently the first face a community will see in the early stages of a mining project.

The results have been phenomenal “super-profits” for private companies like Barrick Gold, Goldcorp and Yamana, who netted a combined $2.8-billion windfall in 2012 from their operating mines, according to the authors. (Canadian mining companies earned a total of $19.3 billion that year.) Between 1998 and 2013, the authors calculate that these three companies averaged a 45% rate of profit on their operating mines when the Canadian economy’s average rate of profit was 11.8%.

Compare this to Canada’s miserly Latin American development aid expenditures of $187.7 million in in 2012—a good portion of this destined for training, infrastructure and legislative reform programs intended to support the Canadian mining sector. Or consider that the same year $2.8 billion was taken out of Latin America by three Canadian mining firms, remittances back to the region from migrants living in Canada totalled only $798 million (much more than Canadian aid).

Without spelling out the long-term social and environmental costs of these operations—costs that are externalized onto affected communities—or going into the problematic ways that private investment and Canadian aid can be used to condition local support for a mine project, Gordon and Webber posit that “super-profits” may be precisely the “Canadian interests” the government’s foreign policy apparatus is set up to defend—not authentic community development, lasting quality jobs or a reliable macroeconomic model.

State support for “militarized neoliberalism”

The argument that the role of the Canadian state is “to create the best possible conditions for the accumulation of profit” is central to Gordon and Webber’s book. From the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) down, Canadian agencies and foreign policy have been harnessed to justify “Canadian plunder of the wealth and resources of poorer and weaker countries.” Furthermore, they write, Canada has actively supported the advancement of “militarized neoliberalism” in the region, as country after country has returned to extractive industry, and export-driven and commodity-fuelled economic growth, which comes with high costs for affected-communities and other macroeconomic risks:

The extractive model of capitalism maturing in the Latin American context today does not only involve the imposition of a logic of accumulation by dispossession, pollution of the environment, reassertion of power of the region by multinational capital, and new forms of dependency. It also, necessarily and systematically involved what we call militarized neoliberalism: violence, fraud, corruption, and authoritarian practices on the part of militaries and security forces. In Latin America, this has involved murder, death threats, assaults and arbitrary detention against opponents of resource extraction.

The rapid and widespread granting of mining concessions across large swaths of territory (20% of landmass in some countries), regardless of who lives there or how they might value different lands, water or territory, has provoked hundreds of conflicts and powerful resistance from the community level upward. In reaction, and in order to guarantee foreign investment, in many parts of the region states have intensified the demonization and criminalization of land- and environment-defenders, while state armed forces have increased their powers, and para-state armed forces expanded their territorial control.

Far from being a countervailing force to this trend, the Canadian state has focused its aid, trade and diplomacy on those countries most aligned with its economic interests. It is not unusual to see public gestures of friendship or allegiance toward governments “that share [Canada’s] flexible attitude towards the protection of human rights,” such as Mexico, post-coup Honduras, Guatemala and Colombia. Meanwhile, Canada has used diverse tactics (in Venezuela and Ecuador, for example) to contain resistance and influence even modest reforms.

Canada’s ‘whole-of-government’ approach in Honduras

One of the more detailed examples in Blood of Extraction of Canadian imperialism in Central America covers Canada’s role in Honduras following the military-backed coup in June 2009. Documents obtained from access to information requests provide new revelations and new clarity into how Canadian authorities tried to take advantage of the political opportunities afforded by the coup to push forward measures that favour big business. Once again, though other economic sectors are discussed, mining takes centre stage.

After the terrible experience of affected communities with Goldcorp’s San Martin mine (from the year 2000 onward), Hondurans successfully put a moratorium on all new mining permits pending legal reforms promised by former president José Manuel Zelaya. On the eve of the 2009 coup, a legislative proposal was awaiting debate that would have banned open-pit mining and the use of certain toxic substances in mineral processing, while also making community consent binding on whether or not mining could take place at all. The debate never happened.

Instead, shortly after the coup, and once a president more friendly to “Canadian interests” was in place following a questionable election, the Canadian lobby for a new mining law went into high gear. A key goal for the Canadian government, according to an embassy memo, was “[to facilitate] private sector discussions with the new government in order to promote a comprehensive mining code to give clarity and certainty to our investments.” Another embassy record said that mining executives were happy to assist with the writing of a new mining law that would be “comparable to what is working in other jurisdictions” and developed with a resource person with whom their “ideologies aligned.”

In a highly authoritarian and repressive context, and under the deceptive banner of corporate social responsibility, the Canadian Embassy—with support from Canadian ministerial visits, a Honduran delegation to the annual meeting of the Prospectors & Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), and overseas development aid to pay for technical support—managed to get the desired law passed in early 2013, lifting the moratorium. Then, in June 2014, with full support from Liberals and Conservatives in the House of Commons and the Senate, Canada ratified a free trade agreement with Honduras, effectively declaring that “Honduras, despite its political problems, is a legitimate destination for foreign capital,” write Gordon and Webber.

Contrary to the prevailing theory in Canada that sustaining and increasing economic and political engagement with such a country will lead to improved human rights, the social and economic indicators in Honduras have gotten worse. Since 2010, the authors note, Honduras has the worst income distribution of any country in Latin America (it is the most unequal region in the world). Poverty and extreme poverty rates are up by 13.2% and 26.3%, respectively, after having fallen under Zelaya by 7.7% and 20.9%. Compounding this, Honduras is now the deadliest place to fight for Indigenous autonomy, land, the environment, the rule of law, or just about any other social good.

A strategy of containment in Correa’s Ecuador

In contrast to how Canada has more strongly aligned itself with Latin American regimes openly supportive of militarized neoliberalism, the experience in Ecuador under the administration of President Rafael Correa illustrates how Canada considers “any government that does not conform to the norms of neoliberal policy, and which stretches, however modestly, the narrow structures of liberal democracy…a threat to democracy as such.”

In the chapter on Ecuador, Gordon and Webber provide a detailed account of Canada’s “whole-of-government” approach to containing modest reforms advanced by Correa and undermining the opposition of affected communities and social movements to opening the country to large-scale mining. A critical moment in this process occurred in mid-2008, when a constitutional-level decree was issued in response to local and national mobilizations against mining. The Mining Mandate would have extinguished most or all of the mining concessions that had been granted in the country without prior consultation with affected communities, or that overlapped with water supplies or protected areas, among other criteria. It also set in place a short timeline for the development of a new mining law.

The Canadian embassy immediately went to work. Meetings between Canadian industry and Ecuadorian officials, including the president, were set up to ensure a privileged seat at talks over the new mining law. Gordon and Webber’s review of documents obtained under access to information requests further reveals that the embassy even helped organize pro-mining demonstrations together with industry and the Ecuadorian government. Embassy records describe their intention “to create sympathy and support from the people” as part of a “a pro-image campaign,” which included “an aggressive advertisement campaign, in favour of the development of mining in Ecuador.” Meanwhile, behind closed doors, industry threatened to bring international arbitration against Ecuador under a Canada–Ecuador investor protection agreement (which a couple of investors eventually did).

Ultimately, the authors conclude, Canadian diplomacy “played no small part” in ensuring that the Mining Mandate was never applied to most Canadian-owned projects, and that a relatively acceptable new mining law was passed in early 2009. While embassy documents show the Canadian government considered the law useful enough to “open the sector to commercial mining,” it was still not business-friendly enough, particularly because of the higher rents the state hoped to reap from the sector. As a result, the embassy kept up the pressure, including using the threat of withholding badly needed funds for infrastructure projects until mining company concerns were addressed and dialogue opened up with all Canadian companies.

Not discussed in The Blood of Extraction, we also know the pressure from Canadian industry continued for many more years, eventually achieving reforms, in 2013, that weakened environmental requirements and the tax and royalty regime in Ecuador. Meanwhile, as the door opened to the mining industry, mining-affected communities and supporting organizations were feeling the walls of political and social organizing space cave in, as they faced persistent legal persecution and demonization from the state itself, while the serious negative impacts of the country’s first open-pit copper mine started to be felt.

Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy”

The Blood of Extraction is a helpful portrait of “the drivers behind Canadian foreign policy.” Gordon and Webber lay bear “a systematic, predictable, and repeated pattern of behaviour on the part of Canadian capital and the Canadian state in the region,” along with its systemic and almost predictable harms to the lives, wellbeing and desired futures of Indigenous peoples, communities and even whole populations. They call it Canada’s “cruel hypocrisy.”

The problem is not Goldcorp or HudBay Minerals, Tahoe Resources or Nevsun. These companies are all symptoms of a system on overdrive, fuelling the overexploitation of land, communities, workers and nature to fill the pockets of a small transnational elite based principally in the Global North. If we cannot see how deeply enmeshed Canadian capital is with the Canadian state—how “Canadian interests” are considered met when Canadian-based companies are making super-profits, even through violent destruction—we cannot get a sense of how thoroughly things need to change.

Jen Moore is the Latin America Program Coordinator at Mining Watch Canada, working to support communities, organizations and networks in the region struggling with mining conflicts.

This article was published in the November/December 2016 issue of The Monitor. Click here for more or to download the whole issue.