by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 23, 2018 | Male Violence

by Heidi Hall / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

I was not yet two years out of an abusive relationship and a series of events had broken my tenuously recovered self into a million small shards – each one bearing a sharp edge to cut me again. He told me to shut the fuck up when he hit me in the face and I had come to the realization that the people around me, consciously or not, were inclined to enforce his demand.

My backpack was sitting in the corner. I only needed to double check my gear and organize some food for me and my best friend – a golden retriever named Oso. I understand it can be both emotionally taxing and dangerous to stand with someone who has become the target of an abusive person. I wish more humans had the courage of a dog.

Then there are the trees and the sky and the bare bones of the granite ridges and the never ending sound of running water and the trail in the morning and the simple living that comes from having nothing more than what you can carry on your back. There was a time when I thought I found solace in nature because it was impersonal. I have since changed my mind. There is a reason I feel much safer with the trees and the mountains and the water than I do with people. I feel loved. Unconditionally.

I remember walking through the forest on the canyon floor next to the river, one foot and one trekking pole after another, far removed from the physicality of hiking with thirty pounds on my back. I cried, I sang bits of songs and cried some more. I worked at putting away my anger at myself for what I had allowed to happen to my life. I became angry with those who had chosen, by their doubt or by their quiet apathy, to support the man who had abused me. I silently screamed “why?” at those who asked for my silence when they did not even know him. I yelled obscenities at a culture which told me if I were obedient he would not have hit me. I plotted the assassination of those who actually gave credence to the idea that he acted in self defense. Some may call this rumination and quite unhealthy. I was once told that some feelings need to be felt until you wear them out. I knew I could not bury this stuff. I chose to feel rather than fester.

And the trees listened. They did not shy away from my anger and tell me I was bad to feel what I felt. They did not say, “but you…” They did not try to tell me what I was really thinking or feeling. They did not try to fix me. They did not insist that my refusal to forgive the man was the real problem. They listened. And I kept walking.

We swam in the river that afternoon and napped on a slab of granite next to a large pool below a broad cascade. I caught a couple of trout to add to our dinner. The next morning we packed up and got on the trail early because we had to ascend an exposed and often hot southeast facing slope. This is stuff I understand. After more than forty years of backpacking I know what my responsibilities are.

We arrived at Bonnie Lake just around lunch time. We had camped here before, the second visit wilder than the first. The Sierra Nevada in California can boil up some real volatile weather in the summer and camping at the lakes near and above timberline may gift you with both humility and common sense if you are willing to learn. The first trip included wind blown rain and aiding the single pole holding up the flapping tarp while I cooked pasta shaped like little peace signs. The second trip involved torrential rain and pounding hail and using stout sticks to dig a canal so the water would continue to flow rather than pool up in our small dry space. We slept on one side of the canal and the kitchen was on the other side. When I went down to the lake to clean my fish there was the sound of a helicopter. I later learned that a group of runners left their cars in the late morning with the intention of running 100 miles through the mountains. They got wet, got scared and called for a ride. The previous day had also produced ferocious thunderstorms and the clouds had begun to build this day shortly after sunrise. I don’t know if the runners were paying attention. I think they may have expected the wilderness to comply with their terms. That is not a relationship – that is exploitation.

Unconditional love was often a topic of lecture in the abusive relationship. I was told over and over and over again that there was something wrong with me because I would not accept pornography as a part of our intimacy. He concluded that I did not love him unconditionally because I would not adopt his values and provide for his needs. I began to associate the concept of unconditional love with the image of a doormat or a bag in a boxing gym or my essence looking over its shoulder as if to walk away. This was exploitation. This was abuse.

On the surface unconditional love simply means love without any condition attached. But unconditional love is not powerlessness. You cannot love if you are dead. There is a self and there are boundaries. And the needs of one lover are no more important than the other.

So I went back to Bonnie Lake for a third time. That time we had wind – a wind which had me inventorying the trees around my campsite for potential falling limbs. If I were killed by a widow maker it would not be because the tree hates me and wants me dead. The rain falls on saints and sinners alike. I am responsible for my own well being and the wilderness will do what it does.There is no guile. There is no manipulation. There are no ultimatums given. There is no need to prove my love by performing on demand like a circus poodle. There are no lies to uncover. There is no insistence that I relinquish my agency to the wilderness and I do not expect the wilderness to bend to my will. And we share a love that is infinite, unconditional and impersonal.

Impersonal was the word that came to me after that third trip to Bonnie Lake. I was wondering if my continuing excursions to a location that seemed to want to beat me up was a kind of unhealthy relationship. I know people who will declare that an abusive man will abuse and it is not to be taken personally but it is really hard to see it that way when you are the one with the bruises. And then when I am in the wilderness I do not feel as though anything is directed at me – it just is. I sat beneath the tarp and laughed and napped, wrapped in my sleeping bag, through hailstorms and wind and cold even when I had wished for sun and warm.

Some people say an abusive person knows no other way to behave but the abuser does have enough self awareness to learn how to mimic the behaviors of someone who does not abuse. They know well enough to cover their tracks.They know precisely how and when to lie. They have the insight to understand when it may benefit them to behave like a decent person. Most abuse goes on behind closed doors. One will only rarely laugh and nap through an afternoon while in a relationship with an abuser.

But I am not certain how I would define unconditional love. I know it is not the gooey eyed infatuation which has one tolerating behaviors that may later infuriate. Nor is unconditional love the process of being subsumed into the life of another out of fear of being alone and unloved (as if love could exist side by side with demands and threats) I carry rain gear and shelter because I have respect for the summer thunderstorms. When I became afraid of my intimate partner I left for the last time.

Most of the time I do not believe there is such a thing as unconditional love. I also feel that in many circumstances the cultural concept of unconditional love is not appropriate. It is not appropriate to shame anyone because they they do not love someone who is abusing them. On the other hand someone who abuses an intimate partner, a friend, a child, an animal or the natural world is the one who deserves to be shamed and shunned.

Our culture insists we must forgive an abuser in order to heal from the abuse. My experience taught me that forgiveness leads to more abuse and I concluded that the idea of forgiveness being anything other than saying that what happened is okay is bullshit. I felt a hell of a lot worse trying to force myself to forgive and then felt worse than that because I could find no reason to forgive a man who battered both me and my dog. Like history and religion I believe the concept of forgiveness is a creation of the victor – not the victim. Or perhaps forgiveness is the creation of the apathetic bystander. Or perhaps forgiveness is preached by those privileged people who have never experienced (or deny experiencing) abuse and don’t want their individual little boat rocked by the waves of reality. Perhaps forgiveness is a clever tool for those who have something to be gained by making life easier for the abuser including the abuser himself. Perhaps unconditional love is no different.

So I came back to Bonnie Lake for the fourth time. I was coaxing a little breeze to ripple the water for my fishing. I spent the entire day exploring one side of the lake in little or no clothing. I swam out and floated on my back looking at the blue of the sky. I pulled out my watercolors and painted while lounging on a beach at a lake at 9,000 feet in elevation. We had a couple of large trout for dinner. That day of my life everything was very, very fine. I believe this is the kind of thing wilderness has to offer anyone who consistently practices personal responsibility and respect in the relationship. Perhaps that is also the root of unconditional love.

I used to believe that everyone is good in some hidden core of their being. I don’t believe that anymore. I think it is life itself which is good and one must love the life they have before they can love anyone or anything else. An abuser loves nothing. Their first victim is their own self.

Perhaps the love I sense in the wilderness is simply the pure joy of life. I can hear it in the water and the bird songs and the soft sounds of walking. I can smell it in the trees and the damp earth. I can feel it when I lie on a warm rock in the sun after a cold swim or when I climb to sit in a sunny spot in the early morning. I can see love in both the clouds and the stunningly clear sky and in the way the stars slowly overtake the darkness after the colors of sunset have faded. I know I am accepted as I am as long as I do no harm and in turn I accept wilderness with all of its danger and uncertainty and I offer my love – unconditionally.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 23, 2017 | Male Violence

by Meghan Murphy / Feminist Current

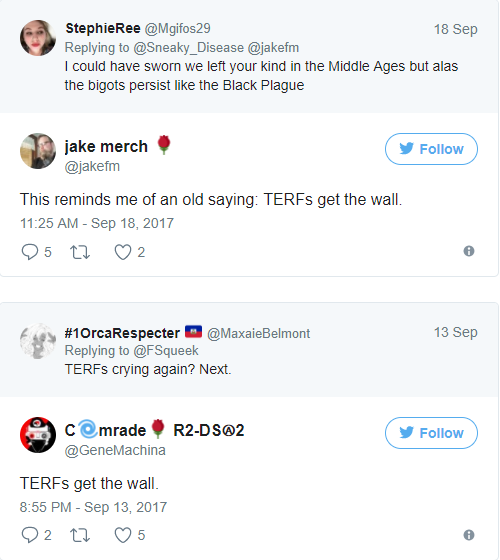

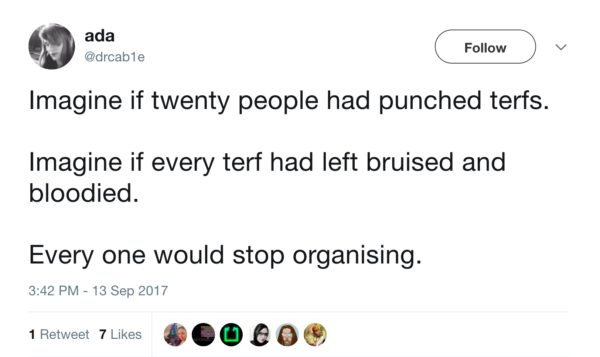

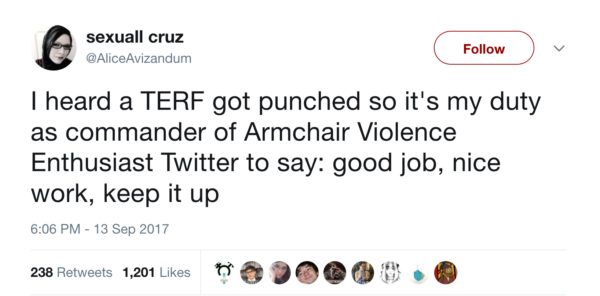

Last week, a 60-year-old woman was beaten up at Speaker’s Corner by several men. She was there with a group of women, who had chosen the historic corner of Hyde Park as a meeting place, before heading off to a talk called, “What is Gender.” The men who punched and kicked Maria MacLachlan had come to protest the women on account of their interest in feminism and in discussing the way new conversations and legislation around “gender identity” could impact the women’s movement and women’s rights. The protestors did not frame their anger and inflammatory rhetoric in this way, though. Instead, they labelled the women “TERFs” (trans exclusionary radical feminists) — a word that has come to signify a modern witch: to be silenced, threatened, harassed, punched, and — yes — killed.

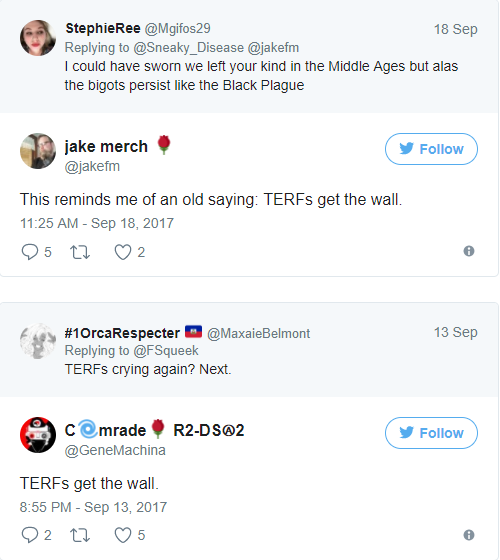

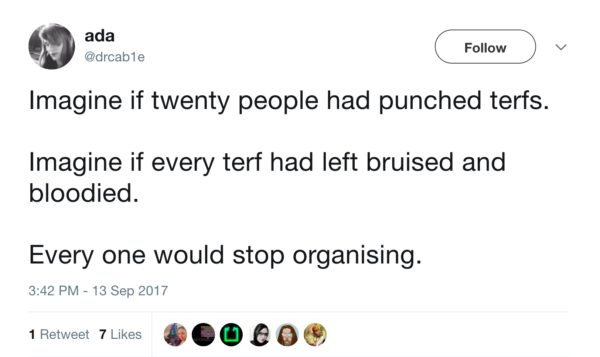

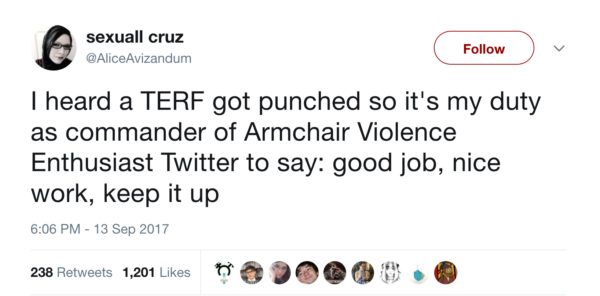

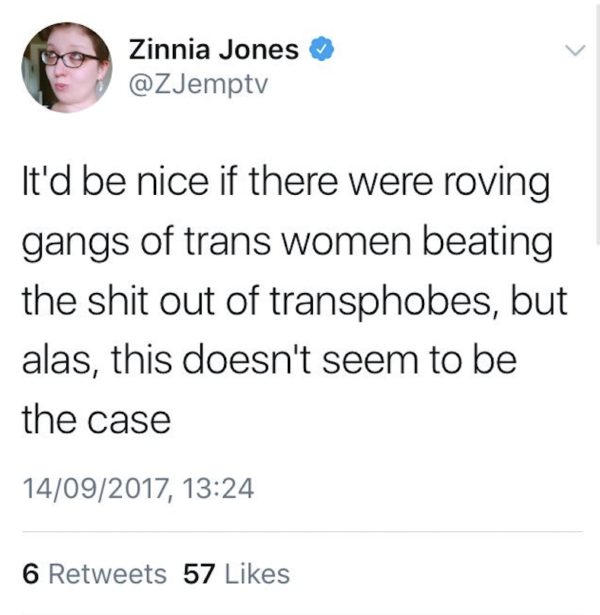

The idea that feminists who question the notion of “gender identity” should be beaten and murdered has very rapidly become accepted by self-described leftists. We’re not just talking about Twitter eggs, here. Men with large platforms who are publicly associated with Antifa and groups like the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) have amplified the “punch TERFs” and “TERFs get the guillotine” message proudly, with the support of their comrades. In reference to The Handmaid’s Tale, many have taken to saying “TERFs get the wall.”

The comparison is a surprisingly (and frighteningly) truthful admission in terms of the intent of these men. “The wall” in The Handmaid’s Tale is where executed bodies are hung, often with placards around their necks that read “Gender Treachery.” The dead bodies serve as a warning to others: do not rebel, do not fight back, do not reject the patriarchal order of things. And this is precisely what these men who use the term “TERF” are saying to women: obey our rule or you will be punished.

Rather than condemning the violence at Speaker’s Corner, numerous trans activists and self-identified leftist men have celebrated and encouraged it.

While some will claim the word “TERF” is neutral, it’s use demonstrates the opposite. It is not a word that women have claimed for themselves — like “slut,” “cunt,” or “bitch,” “TERF” is a word imposed on women to shut them up, bully them, condemn them, smear them, humiliate them, and dismiss them. But more than that: it is a threat. If I think about the times in my life I have been called these words — cunt, bitch, slut — by a man, I have almost always felt the threat of violence behind them. The spitting rage behind those words — the desire to follow through with a punch — is too often present. I have always known these words are used against me as an explicit reminder: you are subordinate. No matter how confident, tough, self-assured, strong, or brave a woman is, these words still put her in her place.

The term, “TERF,” is itself is an intentional manipulation, intended to reframe feminist ideas and activism as “exclusionary,” rather than foundational to the women’s liberation movement. In other words, it is an attack on women-centered political organizing and the basic theory that underpins feminist analysis of patriarchy.

For example, those of us called “TERF” are labelled as such for numerous crimes, including:

- Understanding that women are members of an oppressed class of people (a sex class or caste, as feminists like Kate Millett and Sheila Jeffreys have called it)

- Challenging the notion of innate or internal gender

- Having conversations about “gender identity”

- Questioning whether or not children should begin the process of transitioning

- Associating with or defending women who have been labelled “TERF”

- Understanding that the root of women’s oppression and male supremacy is in biological sex

- Understanding that gender is imposed, and is oppressive/exists to create a hierarchy between men and women.

- Questioning dogma and mantras like “transwomen are women”

- Supporting woman-only space

- Disputing an ideology that claims “male” and “female” are not a material reality

These things are not only not criminal, but are at the root of feminism. In other words, in order to understand how patriarchy works, you must first understand who is a member of the dominant class and who is a member of the subordinate class. You must understand that male violence against women is systemic. You must understand that women are not inherently “feminine,” and that men are not inherently “masculine.” You must be willing to have critical conversations and ask challenging questions about the status quo, about dominant ideology, and about political discourse. You must understand that patriarchy began as a means to control women’s reproductive capacity, and that, therefore, women’s biology is very much central to their status as “less than.” You must understand that feminism is a woman-centered movement, and that women have the right to meet and to organize amongst themselves, without members of the oppressor class (men), to advocate toward their own liberation.

What people are saying when they say “TERF” is “feminist.” It is “uppity woman.” What they mean when they say “exclusionary” is not, as is often claimed, “exclusive of trans-identified people,” but “exclusive of males.” Gender non-conformity is welcomed in feminism — feminism is about not conforming to gender norms. If we were interested in conforming, we would, as is often suggested to us, sit down and shut up.

While “TERF” has always been a slur, what has become clear of late is that it is no longer just that: it is hate speech.

Deborah Cameron, a feminist linguist and professor in language and communication at Oxford, explains that there are key questions we must ask to determine whether a term constitutes a slur, such as:

- Has the term been imposed or has it been adopted voluntarily by the group the term has been applied to?

- Is the word commonly understood to convey hatred or contempt?

- Does the word have a neutral counterpart which denotes the same group without conveying hatred/contempt?

- Do the people the word is applied to regard it as a slur?

Considering the answers to these questions — that, yes, the term has been imposed on feminists, it is always understood as pejorative, it does have a neutral counterpart (i.e. one could just use the term “feminist”), and feminists have consistently stated that the term is a slur — “TERF” is undoubtedly that. Considering that women are the primary target of this slur and that it is commonly attached to threats of (and, as of late, real-life) violence, there is something more we must now contend with.

Following the violent incident at Speaker’s Corner (which was no accident — one of the perpetrators had publicly expressed his intention to “fuck some terfs up”), I have received hundreds of death threats from men online. I’m not alone, either. Any woman who challenged men’s celebration or defense of the violence at Speaker’s Corner became a target. All of these threats have been attached to the term, “TERF.” Feminists have been labelled in this way specifically to dehumanizethem, to spread outrageous lies about their politics (claiming feminists want to kill trans-identified people or that they advocate genocide), to reframe them as oppressors of males who identify as gender non-conforming, and to paint them, generally, as evil witches, therefore deserving of violence.

Proliferating lies about and dehumanizing an oppressed group of people in order to justify abuse is a longtime strategy of racists and xenophobes. Hitler used these tools to commit genocide against the Jews. Indeed, propaganda was a key tool of the Nazis in their efforts to spread antisemitism, quell dissent, and turn people against one another. German newspapers printed cartoons and ads depicting antisemitic images and messages.

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it,” was Hilter’s guiding mantra. He trusted that people wouldn’t think for themselves and would simply act out of fear or intellectual laziness, jumping on bandwagons without thoroughly questioning the purpose and foundation of those bandwagons. The Holocaust was successful because the public went along with it — because individuals believed the myths and lies proliferated by the Nazis, and because they didn’t stand up, think critically, or push back.

While hate speech laws differ from place to place (and can be blurry), as a general rule, making statements intended to expose people to hatred or violence, or that advocate genocide, constitute hate speech.

Because feminists who challenge gender identity ideology are often (strategically) accused of advocating genocide, let’s be clear: “genocide” does not mean arguing that biological sex is a real thing, challenging the idea that femininity and masculinity are innate, or suggesting certain spaces should be for women and girls alone. What genocide does mean is: killing members of an identifiable group or deliberately inflicting conditions of life aimed to bring about the physical destruction of an identifiable group.

In other words, suggesting that feminists should all be destroyed, fired from their jobs, forced into homelessness, harassed, silenced, removed from society, abused, and sent to the Gulag.

Under the law, advocating or promoting genocide is an indictable offence. Likewise, those who promote hatred against an identifiable group or communicate statements in public that incite hatred or violence against an identifiable group that are likely to lead to a breach of the peace (i.e. for example: what happened at Speaker’s Corner) are guilty of an indictable offence.

But these laws are hard to enforce. Which is not necessarily a bad thing. We should not be charging people willy-nilly for things they say on Twitter. What we most certainly should be doing is holding men to account for inciting violence against women and holding media and other institutions to account for normalizing hate speech.

So, beyond the law, let’s talk about accountability. When the media normalizes hate speech, they become culpable. A publication would not use the n-word to describe a black person or the word “kike” to describe a Jewish person. This is because we know that these terms reinforce racism and justify discrimination and/or abuse against particular groups of people who have been historically and systemically oppressed. When the media, institutions, and authorities become aware that a particular term is being used to incite violence against women, it is their responsibility to condemn or simply refrain from encouraging the use of that language.

And yet we have seen various media outlets using the term uncritically, of late.

The fact that the vast majority of those connecting the word “TERF” to threats of violence, death, and genocide are men is notable. The word has been offered up to those who identify as leftists, who have been, on some level, prevented from making misogynistic statements publicly or otherwise advocating violence against women. Their “progressive” credentials meant that they had to maintain a facade of political correctness. But because women labelled “TERF” have been compared to Nazis and bigots, and because trans activism claims to be allied with the interests of the marginalized (despite its overt anti-feminism and individualist ideology), these leftist men have a socially acceptable excuse. Indeed, they seem to revel in it. It’s as if they were given the green light to scream “bitch” (or perhaps “witch” would be more accurate, considering the targeting of specific unruly women to “punch”… or burn…) over and over again, cheered on by their comrades.

If “TERF” were a term that conveyed something purposeful, accurate, or useful, beyond simply smearing, silencing, insulting, discriminating against, or inciting violence, it could perhaps be considered neutral or harmless. But because the term itself is politically dishonest and misrepresentative, and because its intent is to vilify, disparage, and intimidate, as well as to incite and justify violence against women, it is dangerous and indeed qualifies as a form of hate speech. While women have tried to point out that this would be the end result of “TERF” before, they were, as usual, dismissed. We now have undeniable proof that painting women with this brush leads to real, physical violence. If you didn’t believe us before, you now have no excuse.

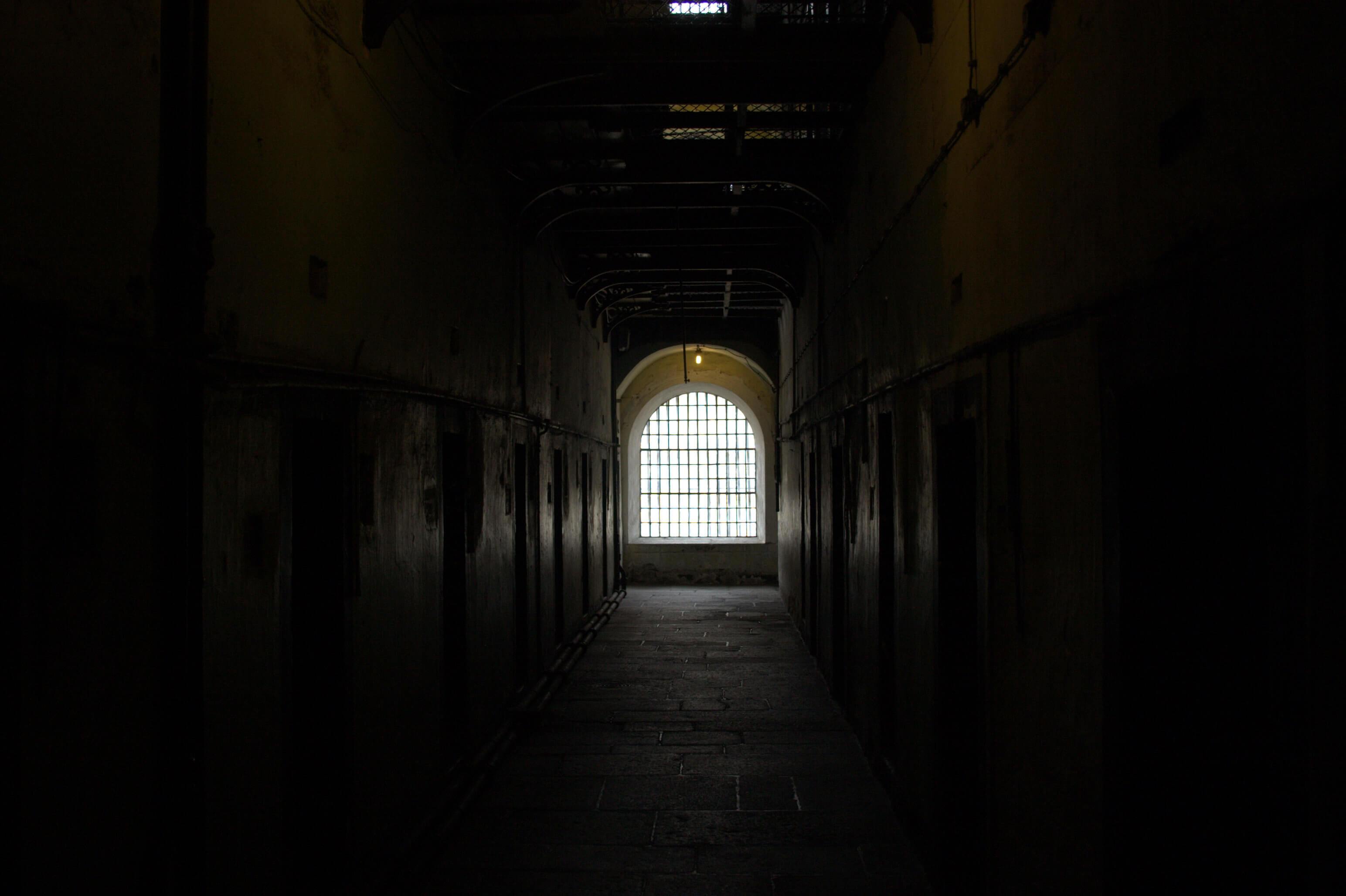

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 30, 2016 | Male Violence

Featured image: Counting Dead Women project

by Karen Ingala Smith / openDemocracy

Across everything that divides societies, we share in common that men’s violence against women is normalised, tolerated, justified – and hidden in plain sight.

Since 25 November last year, at least 118 women and girls in the UK aged over 13 have been killed by men, or a man has been the primary suspect.

An average of one woman dead at the hands of a man every 3 days.

I’ve been recording women’s names and details of how they were killed since January 2012 when Counting Dead Women was launched.

Today we commemorate 653 women.

Men’s fatal violence against women in the UK crosses boundaries of class, race, nationality and age. Over the last year, the oldest woman killed was 85, 18 were over 60, and 21 were aged 25 and under. They included hairdressers, writers, shop assistants, prostituted women, a politician, lawyers, students and school girls; women born in Eritrea, Poland, China, Italy and other countries, and of course women born in the UK with a range of ethnic backgrounds. Most, but not all, were killed by current or former partners, others were killed by burglars, rapists, neighbours, brothers, sons, men they saw as friends or men who paid for sex.

Many think of intimate partner violence, or, more broadly, domestic violence, if they think about women killed by men at all. This focus is reflected and reinforced by official statistics. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) publishes an annual report on violent crime, including homicide. For the year ending March 2015, the Home Office Homicide Index recorded 518 homicides. There were 186 female victims, 331 male victims, and one victim whose sex is unknown/undeclared.

The proportion of female victims was the highest recorded for 20 years. 19 men and 81 women were killed in circumstances described as partner/ex-partner homicides. 31 were killed by other family members (domestic/family violence).

But what about the remaining 74 women? Is it important to have a sex-specific analysis of their deaths?

51-year-old Majella Lynch died in hospital after the a removal of a 400ml shampoo bottle from her abdominal cavity. William Mousley QC, prosecuting, said “The bottle could not have been self-inserted because of the extreme pain such an act would have caused.” Mousley said her attacker, Daniel McBride, 43, an habitual user of hardcore pornography “had an interest in violent sexual activity and was in the mood for sex that night having had an argument with his girlfriend and being rejected by another female.” Yvette Hallsworth, 36, was selected by Mateusz Kosecki because she was “slightly built.” At 18 he was already a predator targeting women in prostitution. He had attacked at least three women who sold sex before he killed Yvette Hallsworth, stabbing her 18 times. Judge Michael Stokes QC described him has having a “fascination, if not an obsession” with prostituted women.

How can a feminist perspective of men’s violence against women disregard some women when patriarchal misogyny, violent sexualisation and objectification are so clear in their murders?

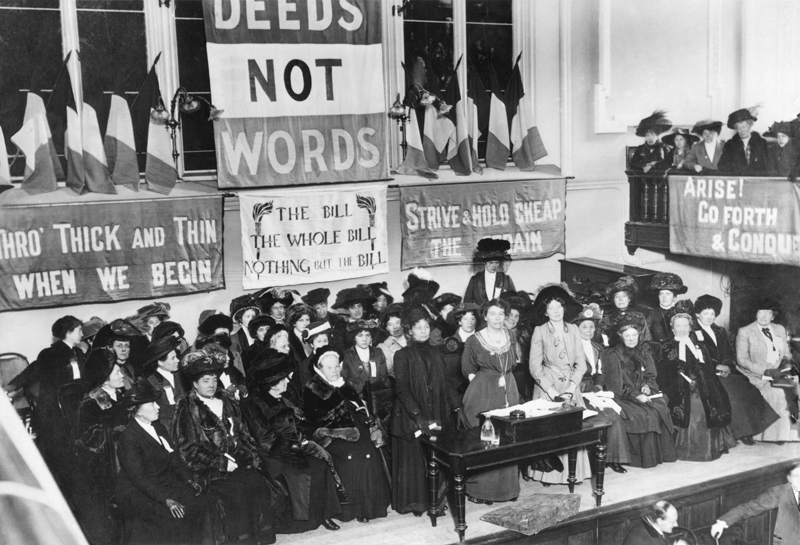

The prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) is globally uneven. Corradi and Stockl, 2014, looked at the relationship between men’s fatal violence against women, feminist activism and government policy in European countries since the 1970s. They found no clear link between rates of IPV and government policies, rather that feminist activism was a crucial catalyst of change – and was most effective when it was independent of government.

“Since the late 1960s, organized women’s activism played a fundamental role in rallying the state to tackle VAW.” (Corradi & Stockl, 2014: 605).

It is estimated that across the world around 66,000 women and girls are violently killed every year. Comparing country-by-country data is challenging, partly because there isn’t a cross-national approach to collecting and disaggregating murder statistics by the sex of both victim and killer, but globally women are at greater risk than men of intimate-partner homicides and are overwhelmingly killed by males. Across everything that divides societies, we share in common that men’s violence against women is normalised, tolerated, justified – and hidden in plain sight, and that there is a lack of truly proactive and deeply rooted state action to protect women’s right to life.

Of course it is essential to look at domestic and intimate partner violence, including homicide; but to focus only on this context not only obscures the full extent of men’s fatal violence against women, it also misses the sex differences within these crimes. In the UK, women are more than 7 times more likely to be killed by a man than men are by a women in the context of intimate partner homicide. Men are more likely than women to be killed by a same-sex partner, and histories of violence before the homicide are different – with men tending to have inflicted months or years of violence and abuse on the women they go on to kill, while women tend to have suffered months or years of violence and abuse from the man they go on to kill.

Responses to men’s violence against women which focus almost exclusively on “healthy relationships,” supporting victim-survivors and reforming the criminal justice system simply do not go far enough. Men’s violence against women is a cause and consequence of sex inequality between women and men. The objectification of women, the sex trade, socially constructed gender, unequal pay, unequal distribution of caring responsibility are all simultaneously symptomatic of structural inequality whilst maintaining a conducive context for men’s violence against women. Feminists know this and have been telling us for decades.

One of feminism’s important achievements is getting men’s violence against women into the mainstream and onto policy agendas. One of the threats to these achievements is that those with power take the concepts, and under the auspices of dealing with the problem shake some of the most basic elements of feminist understanding right out of them. State initiatives which are not nested within policies on equality between women and men will fail to reduce men’s violence against women. Failing to even name the agent – men’s use of violence – is failure at the first hurdle.

Working in partnership, Counting Dead Women and Women’s Aid Federation England, supported by Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and Deloitte, have developed The Femicide Census, a relativity database that allows data to be collated and disaggregated for analysis. It currently contains information regarding over 1000 women who were killed by men between 2009 and 2015. Our intention is to build a research resource than can be used as a tool to influence understanding and policy development. We’ll soon be releasing our first report. In September, our work was cited as an example of good practice in a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women.

Feminists have started Counting Dead Women or femicide count projects in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Counting Dead Aboriginal Women. There is feminist action against femicide on every continent, in countries including Argentina, Peru, Italy, Spain, India.

Women across the world are finding ways to protest the murders of our sisters.

By recording women’s names, and where possible their photographs, we want to create a reminder that women are not reducible to statistics.

653 women dead in the UK in 5 years at the hands of men cannot be 653 isolated incidents. Action is needed and action can be taken to reduce these killings.

Read more articles on openDemocracy in this year’s 16 Days: Activism Against Gender-Based Violence. Commissioning Editor: Liz Kelly

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 12, 2016 | Male Violence, Rape Culture

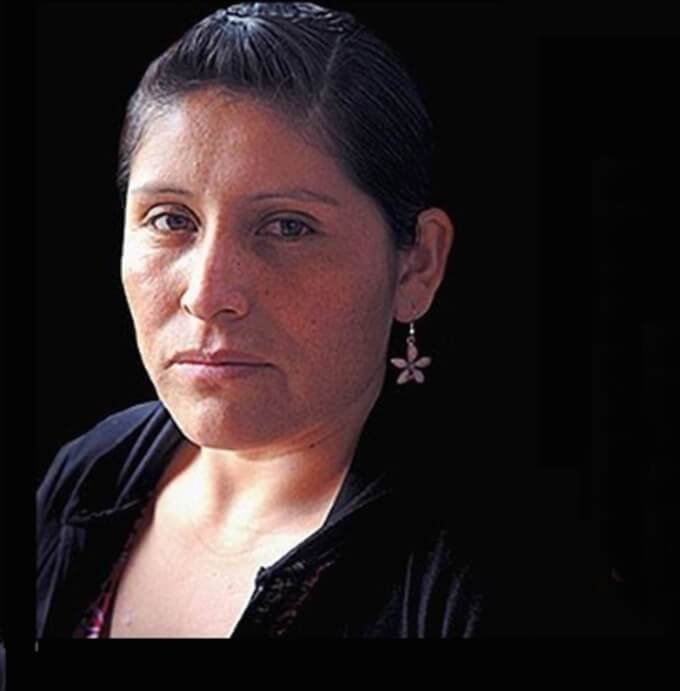

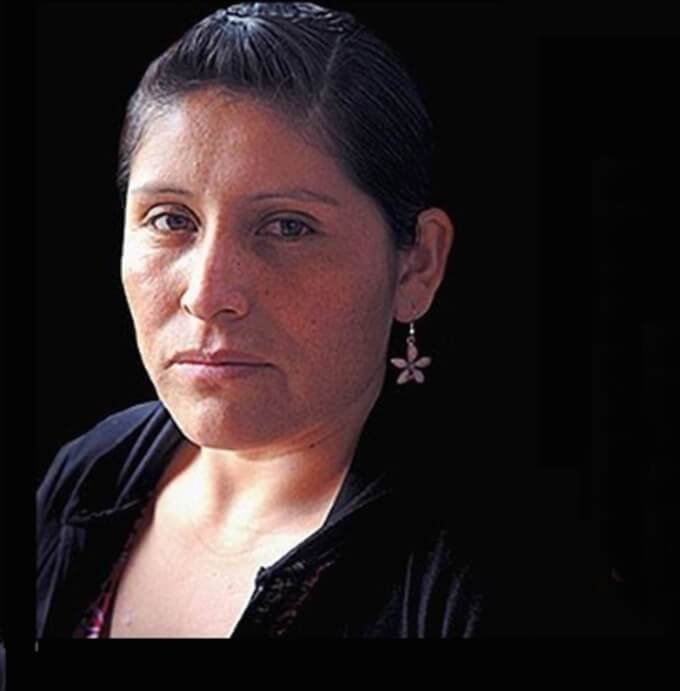

Quechua Bolivian woman unfairly sentenced to life in Argentina

Reina Maraz Bejarano was the last person in the courtroom to understand that she had just been sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly murdering her husband.

Maraz is from an indigenous community in Bolivia. Like many women in rural Bolivian communities, she was raised speaking the local language, not Spanish. On the day she was sentenced by the Argentine justice system, Maraz’s interpreter was translating the judges’ words from Spanish into Quechua so that she could understand. Married at 17 years old, a mother shortly after and subject to a violent marriage, Maraz was 22 when she was arrested for the murder of her husband Limber Santos. She was 26 in November 2014, when her future was determined by three Argentine judges. At that point she had already been imprisoned for four years. Because she couldn’t fully understand Spanish, she spent nearly a year of that jail time without understanding that she was accused of being responsible for her husband’s death.

Maraz’s case is emblematic of the ways in which both the dominant culture and the judicial system abuse women, especially indigenous women. For Maraz, this means being a survivor of physical and psychological violence. Then came the double injustice of being blamed for that violence by the Argentine state. Now she is a victim of a judicial system gone wrong.

A Long Path of Migration and Violence

To tell the story of how Maraz was condemned to life in Argentina’s prisons that day in court in 2014, we have to rewind to 2009, the year Maraz came to Argentina with her husband Limber Santos and their two young boys.

There are more undocumented Bolivian immigrants in Argentina than in any of Bolivia’s major cities. Many migrate from rural areas like Santos’ community in Chuquisaca, Bolivia, and often whole families move. In Maraz’s case she had no choice: her husband threatened to take away their children if she did not accompany him to Argentina.

Maraz testified in court that when they lived together in Bolivia her husband used to get drunk and beat her. Once they were in Argentina, the abuse continued. His family was complicit in the physical violence and took away Maraz’s documents.

After some months in Argentina, the Santos-Maraz family eventually settled in cramped rooms at a brick kiln where they worked in the city of Florencia Varela, in greater Buenos Aires. In a 2013 interview conducted in jail, Maraz’s interpreter translated her words, “Her children never went to school because her husband didn’t want them to. Reina was unhappy, there was never enough money because of Limber’s drinking.”

Santos was going on drinking sessions in the Buenos Aires barrio of Liniers with a man who worked and lived in the kiln also, Tito Vilca Ortiz. Vilca was to play an important role in what happened next.

Reina Maraz – in blue – with her defense lawyer and interpreter in court November 2014. Credit – Agencia ANDAR.

Sexual Violence and ‘that night’

Maraz told in court how one night Limber Santos and Vilca went out drinking. Around 5am, Vilca came back to the kiln and into Maraz’s room, where she was sleeping with the children. He woke her and horrifyingly told her ‘your husband owes me a debt, and he gave me you.’ Then he raped her in front of her children.

The lead judge, Marcela Alejandra Vissio, described the incident as improbable in her verdict because Maraz did not make a police report. But not filing a police report for rape is not unusual for women, who face significant barriers in the legal system such as reliving trauma and being victim-blamed. Data on unreported rape is hard to find in Argentina, as in many countries, but it is likely to be far under-reported. On top of the usual barriers, Maraz has the additional barrier of not fully understanding or speaking Spanish.

The aftermath of Maraz’s rape included a vicious beating at her husband’s hands. It also sparked violent conflict between Vilca and Santos.

On the morning of her husband’s death, 14 November 2010, Maraz got up at 4am to help him prepare for a trip to visit his sister to pay her back a debt. Maraz explained in court that Vilca was also up that morning, drunk. Limber Santos and he started arguing through the window of the room, and then Santos went out. At that moment, Maraz heard the sound of a padlock locking her and the children into the room.

The person who removed the lock and came into the room shortly after was not Maraz’s husband, but Vilca. She asked him where her husband was, and Vilca said Limber Santos had left for his sister’s. Then he raped her again, again in the presence of her two children.

The Aftermath of Limber Santos’ death

Maraz had no idea that her husband was dead at that moment. When there was no sign of him, she went to stay at her father-in-law’s house with her sons. She testified that she was afraid to stay at the brick kiln because of Vilca’s presence. And she went to the police and reported her husband as missing – she was worried he had been robbed when he didn’t appear at his sister’s.

Limber Santos’ body was then found in a rubbish heap on the grounds of the brick kiln. Maraz and Tito Vilca were arrested and jailed as responsible. In jail, Maraz discovered she was pregnant. Her little girl was born in Unit 33 of Prison Los Hornos of Buenos Aires.

It took nearly a full year until Maraz was informed of the charges against her in her own language. The Argentine human rights advocacy organization La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria —‘The Provincial Commission for Memory’ — carried out one of its regular prison inspections in Prison Los Hornos and realized that Maraz was unable to communicate well in Spanish. They brought a Quechua speaker to visit her.

The Battle for an Interpreter

When Maraz faced trial in October 2014, she had Frida Rojas, a Quechua-speaking interpreter, at her side. Accessing this basic right for Maraz took over two years of advocacy and legal formalities, headed by the Commission for Memory.

The battle included a trip to the Supreme Court of Argentina, who ordered the criminal court to provide Maraz with an interpreter. Even so, the Argentine state made the Commission jump through many more hoops to get Maraz the interpreter she had a right to.

Dr. Mariana Katz is in charge of the Commission’s program for Indigenous and Migrant Peoples. Katz is a lawyer, and was an observer at Maraz’s trial. In a recent interview with Intercontinental Cry, Katz said, “In all of these delays and official proceedings, the person who suffers is Reina.”

She went on, “For the Commission, the legal basis [of Maraz’s conviction] is invalid, because from the very first moment [of her arrest] they should have provided her with an interpreter.”

Language Discrimination in Court

In another violation of rights, Maraz’s sister was forbidden by the judges from testifying in her native language, even though the Quechua interpreter was present in court that day.

“When they asked her questions it was clear she didn’t understand, because she was answering something different to the question she was asked,”Katz said. “On top of that, the judges were getting annoyed.”

To convict Maraz, the judges relied on testimony from her 5-year-old son who couldn’t speak Spanish fluidly. “When they brought the boy to declare, he had to be asked the questions several times, because he also has difficulties in Spanish,” explained Katz.

Maraz’s eldest son testified in a Gesell Dome, a one-way mirror system used by law enforcement. Three expert psychologists brought to testify by Maraz’s defense lawyer discredited the Gesell Dome testimony independently of each other. They said it was carried out as an interrogation using leading questions and not as it should be — a psychological test where the child is given time to express themselves through play. Despite all this, the judges did not take into account the three psychologists’ testimony.

The judges also ignored language subtleties that could have led to different interpretations of the boy’s testimony. It was also questionable whether to allow testimony from a 5-year-old who had been subject to traumatic experiences.

More Evidence Dismissed by Judges

Other important evidence was dismissed by the judges. Vilca was also arrested for Santos’ murder. While he was in jail, the Vice Consul of Bolivia to Argentina, Jorge Valentín Herbas Rodriguez, visited him. When Vilca began to tell him the story of what had happened the night of Limber Santos’ death, Herbas stopped him and told him to save it for court. Vilca died in jail before he got a chance to tell his story in court.

Herbas testified at Maraz’s trial. It was clear that Vilca was likely to have made a full confession had he lived. But the judges dismissed the word of the diplomat as “indirect testimony.”

On 11 November 2014, the three judges unanimously declared Maraz guilty of doubly aggravated homicide. The aggravating factors were premeditation and motive of robbery. The judges thought that Maraz and Vilca were lovers and planned to murder Limber Santos for the money he was carrying, which was barely $70US.

For this alleged crime, they condemned Maraz to a life spent in prison.

“They gave Reina the same sentence they give to perpetrators of the genocide [Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’],” Katz said.

Reina Maraz has been condemned to a life in prison. Her appeal is asking for her freedom. Credit -feelsgoodlost on flickr – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Reactions to the Sentence

The gross injustice of the Argentine judicial system did not go unnoticed. Feminist activists from several organizations protested outside the court (and have continued to protest). Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Nobel prize winner and President of the Commission for Memory, wrote an article entitled The 3 Deadly Sins: Woman, Indigenous and Poor.

Maraz’s defense lodged an appeal in Argentina’s Court of Cassation (a certain type of appeal court that examines the interpretation of the law). The Commission together with feminist and human rights organizations have submitted a briefing to the judges (an Amicus Curiae). They stressed that Maraz did not have a fair trial. The vulnerabilities of a non-Spanish speaking migrant indigenous woman were not taken into account by Maraz’s judges, they said.

The demand is for Reina Maraz’s freedom. Failing that, advocates are calling for her sentence to be transmuted to the most lenient sentence for homicide in Argentina, eight years imprisonment, of which she would have already served six. There is no date set yet for the hearing of the appeal.

The Commission believes fully that Maraz is innocent. “We (the Commission) believe in Reina’s innocence, because for nearly 6 years, when she is asked about the facts, she always tells the same story with no cracks,” Katz said. “If it were invented, she would not be able to tell the same story without some level of error. This gives us the certainty that she is innocent.”

An emblematic case of indigenous discrimination

The lead judge Vissio repeatedly stated in her verdict that Maraz, Maraz’s sister Norma Bejarano, and Maraz’s eldest son were all fluent in Spanish. The court treated their need for interpretation of the Spanish language as no more than a defense tactic. The results of this attitude were rights violations; Maraz’s sister and son were never allowed to testify in Quechua.

By Argentine law, this was illegal, but the country’s courts still don’t have interpreters on file for more languages than English, French and Portuguese — notably, all colonial languages.

It’s a symptom of a deep-seated societal norm. “We have a problem in Argentina where people think that there are very few indigenous people, despite the history of indigenous struggle in the country,” Katz said. “There is a cultural conceptualization that indigenous people don’t exist.”

The judges’ actions and verdict speak to this attitude: migrants or indigenous peoples must speak the host country’s or the colonizer’s language; if they don’t, it’s their own fault. It is deeply unfair and deliberate: they are actions that make Indigenous Peoples invisible.

Reina Maraz, Survivor

Maraz was already a survivor of terrible violence; physical and psychological violence committed by her husband and his family, and sexual violence at the hands of Tito Vilca.

Now she is surviving violence at the hands of the Argentine state. Maraz is currently under house arrest, and suffering health problems. House arrest instead of jail was a small comfort achieved by activists, principally so that she can look after her young daughter. Her other two children are in Bolivia with her parents. She hasn’t seen them in a number of years; another type of punishment.

The hope now is that the judges who hear Maraz’s appeal are subject to enough pressure to drop the charges against her.

The Argentine state not only ignored Maraz’s proven status as a Quechua-speaking migrant and so prevented her from accessing a fair trial; they used her vulnerabilities as a weapon to condemn her. These are deeply misogynist and racist actions. Reina Maraz has already been unjustly imprisoned for six years. To free her now would be the bare minimum of justice.

All references come from the author’s original interview with Dr Mariana Katz; La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria’s full coverage of Reina Maraz’s situation and trial; and the verdict of Reina Maraz’s trial.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 8, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Male Violence, Rape Culture

By Terese Mailhot / Indian Country Today Media Network

My auntie says there’s a direct connection between violence against the earth and violence against Indigenous women. I think of my own brown body when she says this, and how it was damaged in childhood and adolescence. My memories feel stolen like the land, stripped like the languages, and entrapped like the bones of our ancestors in government storage.

I’ve spent the last year remembering abuse my father inflicted, and it’s been tough for my brothers, my sister, my babies, and my husband. I spent the morning asking my brother what he can remember, and piecing those fragments to my own. Still, there’s no clear image of the exact chaos my father created. One brother can remember the house turned upside down when he left, another can only remember it might be best to forget, and my loving sister can only say Dad was sadistic. I am unwilling to empathize with him, even though he was emasculated by the government as an Indian man, abused as a child, and institutionalized.

I used to think it was ethnocentric to say Natives didn’t experience abuse before colonialism. I’m on the fence about the topic, still, but I’m willing to make the conceit that sexuality wasn’t contextualized the way it is now as when my nation was thriving. Western construct, the bourgeoisie, and European culture invented the concepts of pedophilia and sexual abuse, so who’s to say that they didn’t also invent the acts. Whether Indigenous children or women experienced sexual violence before colonization is debatable, but I think the debate is sullied by Western thought and colonization, like so many things.

I feel like there’s a direct connection between the memories that feel stolen from me and the land Indigenous people grieve for. Within colonial log transcript, one will find that sexual violence pervaded Indigenous communities as a means to sublimate and de-humanize the people. How could the violence inflicted upon me be removed from this? It feels inherited. I’m not a soft-hearted woman who would say my father hurt women because someone hurt him, but I can say without question that I have been hurt by men because of the historical violence against Indigenous women. Just like the categorization of sexuality sprouted from Western thought, so did sexual violence as a means to colonize. Violence against Indigenous women is too common. The sexualization of Indigenous women is familiar to all North Americans. The “squaw,” and “savage,” imagery remains constant within our society. Colonization was successful in its ability to invite the degradation of our women. It’s practically promoted. One only has to observe the way Indigenous women go missing in Canada to see how prevalent the issue is.

I had panic attacks when I first started remembering. My bones felt immovable, and my eyes felt obscene in the light of day, and my body felt dirty. There’s a connection looming in my mind between the countless artifacts our government and museums have excavated from Indigenous lands and how much my memories feel locked away. The truth of my life, my memory, can’t be found within white institutions like hospitals. It can only be found beneath the iconography and stories of my culture. There’s a story that women where I’m from were given two items when they could speak: a club and a fishing weir. One item to protect, and another to provide. When the girl speaks with her items for the first time, she declares that she has a club and a weir, and asks the world which they want from her. Women where I’m from must protect themselves and provide for the community. After Indian boarding school, our communities stopped practicing the ceremony. Women were left clubless when the club was crucial. Through decolonization, the story has been excavated and a metaphorical club has been given to me.

I stand with my club, and carry the ability to nourish my children, my family, and my community. The connection for me is as irrefutable as my body, which can be broken, subject to discrimination, ignorance and judgment. The connection between my body and my land is one of the few things colonialism couldn’t take from me. As I journey towards reconciliation with my body, I feel like I am no longer invisible, and that I am taking up space within a continuum of historical erasure.

Terese Marie Mailhot is from Seabird Island Indian Band. Her work has been featured in The James Franco Review, The Offing, and Yellow Medicine Review. She’s a student at the Institute of American Indian Arts and she is a Discovery Fellowship recipient.

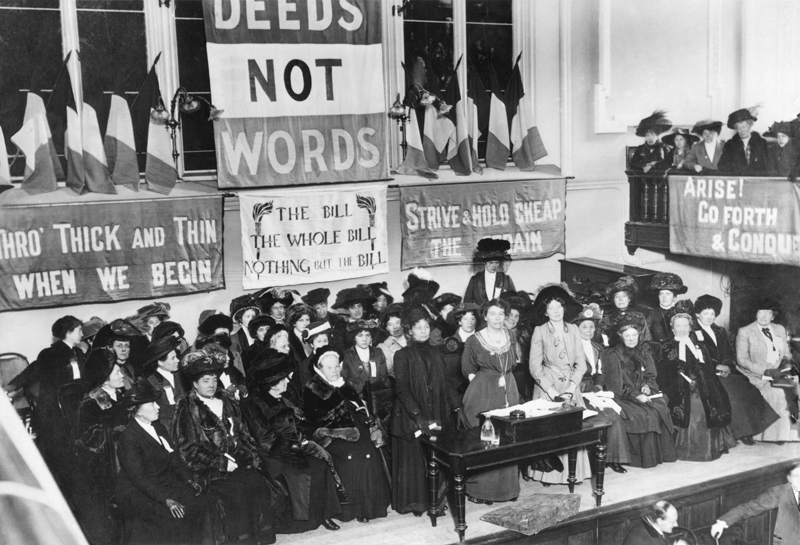

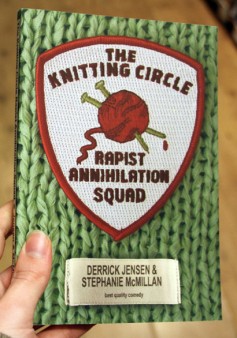

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 13, 2016 | Male Violence, Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis, Women & Radical Feminism

This is the second part of a series. Read the first part at Toward Strategic Feminist Action.

By Tara Prema / Gender is War

Developing an effective response to the worldwide crisis of male violence

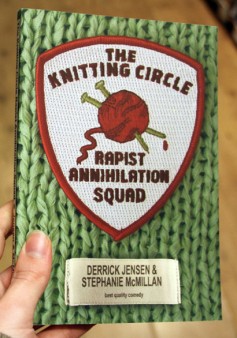

Strategic Feminism is a framework for collective action against patriarchal violence. The framework is based on acknowledging that the struggle for women’s liberation can – and must – adapt the lessons of asymmetric conflicts, such as guerrilla uprisings against occupying armies. We can apply the lessons of successful insurgencies to our aboveground organizing. And we must do so. It is a matter of life and death: every minute, men rape, abuse, abduct, and murder girls and women. Time is short – we must prepare for worse still to come.

Strategic Feminism draws on the excellent analysis of asymmetric conflict in Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. In Part One, we discussed the crisis of male violence against women and sketched a solution based on organizing for action in our communities. Here in Part Two, we look at more ways to begin and sustain our work for radical social change.

We call this model Strategic Feminism because it’s outcome-oriented and focused on creating a movement that addresses the material conditions affecting women’s lives.

Sustaining a movement: Feminism in collapse

How can we create a movement in a time of collapse? How do we come together as a force for change when individuals burn out, groups fall apart, and coalitions fracture? When feminists are fighting each other on questions of gender, motherhood, sexuality, and privilege?

And how to do we take these steps now, when every day brings more signs of cultural, economic, and environmental collapse? How do we adapt our strategies to a world order that is reeling from one crisis to the next? This is our challenge.

As radical women, we must pledge to protect each other and the places we love, just as women have done since the time they burned us as witches.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit

At the core of this movement, there is an intangible force with a measurable impact. It’s an attitude, a mindset, a determination that compels us to push back against oppression. It’s the warrior mindset, the stand-and-fight stance of someone defending her home and the ones she loves.

Many burn with righteous anger. This is important – anger lets us know when people are hurting us and the ones we love. It’s part of the process of healing from trauma. Anger can rouse us from depression and move us past denial and bargaining. It is a step toward acceptance and taking action.

Rewriting the trauma script includes asserting our truth and lived experiences, and naming abuses instead of glossing over them. It includes discovering (and rediscovering) that we can rely on each other instead of on men. It’s mustering the courage to confront male violence. But it’s not going to be easy.

Acknowledge and #NameTheProblem

We can’t fight a problem we can’t identify, especially when it is deliberately obscured. It’s not surprising that naming the problem has become a political act. And the problem is male violence against women. We shouldn’t have to say “she was raped” when we know that “men raped her.”

Reclaim what was taken from us

- Learning (and re-learning and reminding each other) that our bodies and spirits belong to us, we deserve to be safe, and we have the capacity to defend ourselves

- Fighting isolation and connecting with other women who have a similar fighting spirit

- Creating a culture of resistance to male violence

Taking action

Strategies are the paths to the goal. Tactics are the means to implement strategies. Part of a strategy for sustaining a movement is networks of peer support, mutual aid, and solidarity. We start by coming together with our peers, women who share the same goals and principles.

Goal: Develop a thriving network capable of effective action

Strategy: Find women allies and start a group

Tactics:

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.- When you get an invitation, go!

- Use a petition or sign-on letter to gather potential recruits.

- Screen and interview volunteers.

- Discuss and write up a basis of unity

- Hold meetings, discussions, films, work parties, and benefit shows.

- Keep a signup sheet and a list of participants.

- Retain volunteers through appreciation and peer support.

- Raise money for projects and community campaigns.

Strategy: Start with an existing group

- Entryism – add members until your crew has a majority

- Headhunting – join in order to recruit members to your group

- Affinity group – organize an action team within the group

- Symbiosis – utilize the group’s resources and membership for your project

Strategy: Build a coalition

- Circulate a sign-on letter

- Organize against a common political enemy

- Host an event: A symposium, press conference, rally, or direct action

- Pledge to support and not publicly denounce each other

- Collaborate together on an ongoing project

Strategy: Keep each other safe and supported

- Have designated safe houses and emergency plans

- Set up a legal defence fund and legal team before they’re needed

- Create a mutual aid network so women activists can support each other

- Make and distribute an activist safety/security plan to stop online hackers and physical attackers

- Prioritize peer support and peer counseling, whether it’s formal or informal.

- Keep a “not wanted” list to weed out known disruptors

- Host group self-defense and security awareness trainings

Choosing our battles

How do we decide on a particular project, campaign, action or strategy? We can ask:

- Is it effective? What will it achieve?

- What are our goals (immediate and long-term )? How does this action lead there?

- Who is working with us?

- Do we have community support? From which communities?

- What decision-makers are we targeting?

- What are our strategies and tactics? (Legal, confrontational, revolutionary?)

- Do we have the resources? (People power, funds, vehicle?)

- How can we get the resources? (Recruiting, crowdfunding, direct appeals?)

- What are the possible negative outcomes? How can we mitigate the negatives?

Some actions and projects aren’t intended to lead to concrete results – they are symbolic in nature but still useful for boosting morale, getting media attention, and recruiting volunteers.

Male allies

Male allies can – and should – make substantial contributions to the movement. Consider asking women what we need to sustain our work, and then providing that without judgment or trying to exercise veto power. Men who take on ally roles should turn to other men for peer support and take time to debrief with them regularly.

Remember to regroup

Every campaign, project, and group will stall eventually. We invariably reach the point when it seems our efforts are going nowhere and our adversaries are dragging us down. This is when we must re-group and re-commit ourselves or fail. Every goal worth fighting for is going to face a serious backlash from those in power.

In spite of all our planning, our groups and coalitions still fall apart due to lack of unity, loss of commitment, burnout, and the divisive pressures of racism, classism, misogyny, and disruption from outsiders. Overall, things are not going to get better on their own. In the endgame of capitalism, the situation for women as a class worldwide is deteriorating at a fearsome rate. It’s up to us to prepare for the worst.

In the short term, this anti-feminist backlash is intensifying. Planning now is crucial. Some readers may not see the immediate need for this laundry list of tactics and strategies. But the day is coming when the need for community networks of trust will be urgent, because so much of what we rely on now has collapsed.

These notes come from unceded indigenous territory on the frontier of resistance to the western patriarchal invasion.

Keeping the spirit

Keeping the spirit Start with a small circle: each one invite one.

Start with a small circle: each one invite one.