by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 23, 2018 | Male Violence

by Heidi Hall / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

I was not yet two years out of an abusive relationship and a series of events had broken my tenuously recovered self into a million small shards – each one bearing a sharp edge to cut me again. He told me to shut the fuck up when he hit me in the face and I had come to the realization that the people around me, consciously or not, were inclined to enforce his demand.

My backpack was sitting in the corner. I only needed to double check my gear and organize some food for me and my best friend – a golden retriever named Oso. I understand it can be both emotionally taxing and dangerous to stand with someone who has become the target of an abusive person. I wish more humans had the courage of a dog.

Then there are the trees and the sky and the bare bones of the granite ridges and the never ending sound of running water and the trail in the morning and the simple living that comes from having nothing more than what you can carry on your back. There was a time when I thought I found solace in nature because it was impersonal. I have since changed my mind. There is a reason I feel much safer with the trees and the mountains and the water than I do with people. I feel loved. Unconditionally.

I remember walking through the forest on the canyon floor next to the river, one foot and one trekking pole after another, far removed from the physicality of hiking with thirty pounds on my back. I cried, I sang bits of songs and cried some more. I worked at putting away my anger at myself for what I had allowed to happen to my life. I became angry with those who had chosen, by their doubt or by their quiet apathy, to support the man who had abused me. I silently screamed “why?” at those who asked for my silence when they did not even know him. I yelled obscenities at a culture which told me if I were obedient he would not have hit me. I plotted the assassination of those who actually gave credence to the idea that he acted in self defense. Some may call this rumination and quite unhealthy. I was once told that some feelings need to be felt until you wear them out. I knew I could not bury this stuff. I chose to feel rather than fester.

And the trees listened. They did not shy away from my anger and tell me I was bad to feel what I felt. They did not say, “but you…” They did not try to tell me what I was really thinking or feeling. They did not try to fix me. They did not insist that my refusal to forgive the man was the real problem. They listened. And I kept walking.

We swam in the river that afternoon and napped on a slab of granite next to a large pool below a broad cascade. I caught a couple of trout to add to our dinner. The next morning we packed up and got on the trail early because we had to ascend an exposed and often hot southeast facing slope. This is stuff I understand. After more than forty years of backpacking I know what my responsibilities are.

We arrived at Bonnie Lake just around lunch time. We had camped here before, the second visit wilder than the first. The Sierra Nevada in California can boil up some real volatile weather in the summer and camping at the lakes near and above timberline may gift you with both humility and common sense if you are willing to learn. The first trip included wind blown rain and aiding the single pole holding up the flapping tarp while I cooked pasta shaped like little peace signs. The second trip involved torrential rain and pounding hail and using stout sticks to dig a canal so the water would continue to flow rather than pool up in our small dry space. We slept on one side of the canal and the kitchen was on the other side. When I went down to the lake to clean my fish there was the sound of a helicopter. I later learned that a group of runners left their cars in the late morning with the intention of running 100 miles through the mountains. They got wet, got scared and called for a ride. The previous day had also produced ferocious thunderstorms and the clouds had begun to build this day shortly after sunrise. I don’t know if the runners were paying attention. I think they may have expected the wilderness to comply with their terms. That is not a relationship – that is exploitation.

Unconditional love was often a topic of lecture in the abusive relationship. I was told over and over and over again that there was something wrong with me because I would not accept pornography as a part of our intimacy. He concluded that I did not love him unconditionally because I would not adopt his values and provide for his needs. I began to associate the concept of unconditional love with the image of a doormat or a bag in a boxing gym or my essence looking over its shoulder as if to walk away. This was exploitation. This was abuse.

On the surface unconditional love simply means love without any condition attached. But unconditional love is not powerlessness. You cannot love if you are dead. There is a self and there are boundaries. And the needs of one lover are no more important than the other.

So I went back to Bonnie Lake for a third time. That time we had wind – a wind which had me inventorying the trees around my campsite for potential falling limbs. If I were killed by a widow maker it would not be because the tree hates me and wants me dead. The rain falls on saints and sinners alike. I am responsible for my own well being and the wilderness will do what it does.There is no guile. There is no manipulation. There are no ultimatums given. There is no need to prove my love by performing on demand like a circus poodle. There are no lies to uncover. There is no insistence that I relinquish my agency to the wilderness and I do not expect the wilderness to bend to my will. And we share a love that is infinite, unconditional and impersonal.

Impersonal was the word that came to me after that third trip to Bonnie Lake. I was wondering if my continuing excursions to a location that seemed to want to beat me up was a kind of unhealthy relationship. I know people who will declare that an abusive man will abuse and it is not to be taken personally but it is really hard to see it that way when you are the one with the bruises. And then when I am in the wilderness I do not feel as though anything is directed at me – it just is. I sat beneath the tarp and laughed and napped, wrapped in my sleeping bag, through hailstorms and wind and cold even when I had wished for sun and warm.

Some people say an abusive person knows no other way to behave but the abuser does have enough self awareness to learn how to mimic the behaviors of someone who does not abuse. They know well enough to cover their tracks.They know precisely how and when to lie. They have the insight to understand when it may benefit them to behave like a decent person. Most abuse goes on behind closed doors. One will only rarely laugh and nap through an afternoon while in a relationship with an abuser.

But I am not certain how I would define unconditional love. I know it is not the gooey eyed infatuation which has one tolerating behaviors that may later infuriate. Nor is unconditional love the process of being subsumed into the life of another out of fear of being alone and unloved (as if love could exist side by side with demands and threats) I carry rain gear and shelter because I have respect for the summer thunderstorms. When I became afraid of my intimate partner I left for the last time.

Most of the time I do not believe there is such a thing as unconditional love. I also feel that in many circumstances the cultural concept of unconditional love is not appropriate. It is not appropriate to shame anyone because they they do not love someone who is abusing them. On the other hand someone who abuses an intimate partner, a friend, a child, an animal or the natural world is the one who deserves to be shamed and shunned.

Our culture insists we must forgive an abuser in order to heal from the abuse. My experience taught me that forgiveness leads to more abuse and I concluded that the idea of forgiveness being anything other than saying that what happened is okay is bullshit. I felt a hell of a lot worse trying to force myself to forgive and then felt worse than that because I could find no reason to forgive a man who battered both me and my dog. Like history and religion I believe the concept of forgiveness is a creation of the victor – not the victim. Or perhaps forgiveness is the creation of the apathetic bystander. Or perhaps forgiveness is preached by those privileged people who have never experienced (or deny experiencing) abuse and don’t want their individual little boat rocked by the waves of reality. Perhaps forgiveness is a clever tool for those who have something to be gained by making life easier for the abuser including the abuser himself. Perhaps unconditional love is no different.

So I came back to Bonnie Lake for the fourth time. I was coaxing a little breeze to ripple the water for my fishing. I spent the entire day exploring one side of the lake in little or no clothing. I swam out and floated on my back looking at the blue of the sky. I pulled out my watercolors and painted while lounging on a beach at a lake at 9,000 feet in elevation. We had a couple of large trout for dinner. That day of my life everything was very, very fine. I believe this is the kind of thing wilderness has to offer anyone who consistently practices personal responsibility and respect in the relationship. Perhaps that is also the root of unconditional love.

I used to believe that everyone is good in some hidden core of their being. I don’t believe that anymore. I think it is life itself which is good and one must love the life they have before they can love anyone or anything else. An abuser loves nothing. Their first victim is their own self.

Perhaps the love I sense in the wilderness is simply the pure joy of life. I can hear it in the water and the bird songs and the soft sounds of walking. I can smell it in the trees and the damp earth. I can feel it when I lie on a warm rock in the sun after a cold swim or when I climb to sit in a sunny spot in the early morning. I can see love in both the clouds and the stunningly clear sky and in the way the stars slowly overtake the darkness after the colors of sunset have faded. I know I am accepted as I am as long as I do no harm and in turn I accept wilderness with all of its danger and uncertainty and I offer my love – unconditionally.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 18, 2018 | Male Supremacy

Women cannot possibly be viewed human so long our humanity is determined by men’s circumstantial “civilization.”

by Julian Vigo / Feminist Current

Catharine MacKinnon’s book, Are Women Human? is riddled with examples of violence specifically targeting women. From beatings, to torture, to rape, to sexual subjugation, to murder, and to genocide, there are myriad examples that show how women are rendered insignificant in the cultural landscape of human rights. MacKinnon’s text asks how women can be considered people since, when placed next to legal renderings of other groups of people, women are excluded from similar protections. She writes:

“Women not being considered a people, there is as yet no international law against destroying the group women as such. ‘Sex’ is not on the list of legal grounds on the basis of which destruction of peoples as such is prohibited. For women as such, there is no legal equivalent to genocide… presumably because it is commonplace, built into the relative status of the sexes in everyday life.”

“Are women human?” remains a question of great significance today, as even those on the left consider us less-than. There is also the fact that, for many, women’s rights are considered “already won” and therefore part of an antiquated movement that should just simmer down.

But the facts speak for themselves: women are still underrepresented in employment in media, government, and education; women bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work; while women are shown to make better use of loans, they are denied loans at a far higher rate than men; women will statistically be more prone to enlisting in credit repair services and accruing far more debt than men despite performing most of the world’s labour, earning on average 24 per cent less than men; and women are more likely to suffer from poor credit due to their relationships with men and through marriage. There are so many facts that show women are saddled with more work, lower salaries, and fewer economic benefits, no matter what level education they attain, no matter their financial investments, regardless of the few who manage to climb far up the ladder. While today, womanhood is still reduced to the superficial — “beauty,” attained or displayed through symbols of femininity, like hair, makeup, jewelry, and clothing — women’s realities are anything but decorative or camp. Women’s lives are still overwhelmingly difficult, as the burden placed on women to undertake unpaid domestic labour while being forced to pay more for beauty, hygiene, and health products stands in stark contrast to what men experience.

From articles that claim feminism is “going too far,” to the recent labelling of women who name sexual harassment and assault as taking part in a “witch hunt,”men are being positioned as victims of women’s efforts to fight misogyny. Sexism is so normalized, any challenges to it are viewed as an unreasonable attack on men.

Recently, acclaimed classicist and feminist, Mary Beard, painted herself into a corner over the Oxfam scandal. In response to reports that the former country director of Oxfam in Haiti, Roland Van Hauwermeiren, had bought sex from women and girls, she tweeted:

“Of course one can’t condone the (alleged) behaviour of Oxfam staff in Haiti and elsewhere. But I do wonder how hard it must be to sustain ‘civilised’ values in a disaster zone. And overall I still respect those who go in to help out, where most of us [would] not tread.”

This kind of comment exemplifies the way women (particularly women living in the Global South and women of colour) have historically been othered — their humanity rendered less legitimate than men’s. Beard’s comments have been described as “genteel racism,” as well as as patently sexist, and the reality is that they are both. This kind of response demonstrates the extent to which sexism has been normalized within the cultural subconscious of society, as well as the way the colonialist gaze positions dark-skinned bodies as provoking white man’s loss of “civility.”

Defending men’s violence and exploitation on account of disaster or difficult circumstances is not exactly new. From the well-documented cases of increased trafficking of females from ages 10 to 24 in India after natural disasters strike, to the recent U-turn in Russian law decriminalizing wife-beating because of the belief that the removal of this “right” posed a threat to men’s “traditional values” and masculinity, there is no paucity of examples at to how the humanity of men is positioned front and centre.

Considering her work in Women & Power: A Manifesto, which analyzes the cultural unconscious of misogyny, as well as her extensive work in the fields of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations, it is clear that Beard is skilled at analyzing misogyny in ancient cultures. Her failure to see it in today’s modern culture reveals a troubling (but common) blindspot. Indeed, her comments exist as part of a larger trajectory of British intellectual history and a long tradition of white, male colonization.

Terms like “civilized” beings, “disaster zones,” and “areas that most of us would not tread” are reappropriations of the same patriarchal language that have historically kept whites the colonizers of dark-skinned bodies and males the proverbial “owners” of females. Beard’s phrasing suggests that it is not the male Westerner who is uncivilized, but rather his proximity to the non-Western “zone” and conditions of “disaster” that leads him to behave in this suddenly “uncivilized” way.

Beard is not alone in thinking this way. Too many progressives cannot recognize misogyny when it happens within particular contexts and excuse it circumstantially. We see this in the way the left has excused prostitution and pornography, in terms of the vast numbers of women who are raped by relief workers in Syria, and when we look at the recently reported assaults on and harassment of female aid workers by male staff. But even if Beard’s words are not excusing the acts of rape by relief workers, they reveal a view that women’s bodies must bear the brunt of men’s “civilization” (or lack thereof).

I took a picture in my first months in Haiti while working on child protection projects in Port-au-Prince showing two tents — one factory made, the other a series of bed sheets put together on a clothesline hung upon trees. All around: the rubble from buildings that fell during the 2010 earthquake. The buildings in Haiti fell largely due to shoddy building materials and lack of steel reinforcements, as expensive cement from the US forced many contractors to pour in more sand and less concrete, creating a weaker structure, meaning that this particular disaster was very much man-made. In other words, these sites of “disaster” are created by the very “civilized” men who turn around and exploit the victims of their imposed “civilization.”

Cheapened materials sold at extortionate rates to a people whose lives are dictated by Western G7 powers results in destroyed infrastructure and situationstraffickers take advantage of. Where Beard sees chaos, I see a legacy of colonial encounters and the buttressing of colonial institutions. Let us not forget that it was the British elite who unwittingly engineered the murders of at least one million people and the rapes of thousands of women by hastily planning the Great Partition, continuing the British rule which segregated Indian society along the lines of religion, creating acrimony in a country that had previously been united. This would turn out to be one of the most politically catastrophic decisions made by the UK’s most “civilized” leaders.

Image: March 2010, Port-au-Prince (Photo credit: Julian Vigo)

Several generations of male colonialists have brought us this still present view of “foreign” female bodies as objects of curiosity and the mechanisms responsible for interrupting their “civilized” gaze. We have seen this metaphor of savagery throughout history. In Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz discusses the “Chingada,” a term which references the systemic rape of women during the Conquest of Mexico by Cortès. He writes:

“[I]t is possible to answer the question, ‘What is the Chingada?’ The Chingada is the Mother forcibly opened, violated, or deceived. The hijo de la Chingada is the offspring of violation, abduction or deceit. If we compare this expression with the Spanish hijo de puta (son of a whore), the deference is immediately obvious. To the Spaniard, dishonour consists in being the son of a woman who voluntarily surrenders herself: a prostitute. To the Mexican it consists in being the fruit of a violation.”

Paz’ insight into how colonial encounters in the Americas were directly tied to the violation of female bodies serves as looking glass into later centuries, wherein women were similarly violated through enslavement, rape, and the exchange of their bodies.

In the late 19th century, explorers returning from faraway lands attempted to authenticate their experiences by taking the “real native” from their habitats, bringing their captives back to the West, and putting them on display in the World’s Fairs popular during this time. From the Khoikhoi (in the West, known by the derogatory term, “Hottentots”) of Botswana who were displayed in fairs from Britain to France, to the Indigenous Americans on display at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, to the Apaches and Igorots of the Philippines on display at the Saint Louis World’s Fair in 1904, the black and brown body was something of a boon in the scene of freak shows that toured Europe and North America.

The ethos of these males who peddled in the trafficking of women is astonishingly contradictory, just as the aid workers raping and exploiting women in Haiti today: on the one hand, these men set out to instill upon the native, “dark-skinned other” their supposedly progressive values, and on the other, these men set up their objects of curiosity as caged spectacles, imprisoned as a means for the white Westerner to understand their own humanity. These World’s Fair installations were part of the rise of both eugenics and social sciences in the 19th century — specifically ethnology, where people were put on display in human zoos to show Westerners how people around the world lived in what was believed to be an “rapprochement” between West and East, even if entirely curated. The obvious problem with these zoos and expositions is that there was little consciousness at the time about how these “natives” felt about being kidnapped and enslaved.

Where these fairs concerned women, the stories were always the same: kidnapping, sexual slavery, freak shows, then death. Sarah Baartman was taken from the Gamtoos Valley in the Eastern part of the Cape Colony (present-day South Africa) and brought to England in 1810. Bought and sold from handler to handler and shown at various fairs in England and Ireland, she was exhibited as part of a freak show under the name “Hottentot Venus.” Finally, in 1814, she was brought to the Palais Royal in Paris where she was enslaved and became the object of scientific study.

Where these fairs concerned women, the stories were always the same: kidnapping, sexual slavery, freak shows, then death. Sarah Baartman was taken from the Gamtoos Valley in the Eastern part of the Cape Colony (present-day South Africa) and brought to England in 1810. Bought and sold from handler to handler and shown at various fairs in England and Ireland, she was exhibited as part of a freak show under the name “Hottentot Venus.” Finally, in 1814, she was brought to the Palais Royal in Paris where she was enslaved and became the object of scientific study.

Parallel to male colonizers sexually objectifying women during this time were French scientists who were interested in knowing the size of black women’s labia. The head of the menagerie at the Muséum national d’Histoire, Georges Cuvier, used Baartman in his new discipline, comparative anatomy, developing his theory that Baartman was the “missing link” between humans and animals, with Cuvier referring to her as an “orangutan” and a “monkey.”

Baartman died in 1815 at the age of 25. After her death, Cuvier dissected her body, displaying her remains. Her brain, genitals, skeleton, and a plaster cast of her body were on display until 1974 at the Musée de l’Homme, not repatriated to Hankey, South Africa until 2002. For all the scientific knowledge Cuvier hoped to amass by violating and dissecting Baartman’s body, what he really brought to light was the kind of “civilized” behaviour Western culture interprets as “normal.” Indeed, generations of violations against dark-skinned bodies have had the effect of normalizing rape as a necessary part of civilization.

What would lead someone like Beard to view women as necessary victims of male violence and white male “civility” as something that comes and goes like a headache? The question surrounding our humanity didn’t begin with women’s absence from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, nor did it begin with Sarah Baartman’s labia on display for over 150 years. The answer to the question, “Are women human?” lies somewhere between these historical moments and our modern excusing of men’s abusive behaviour, supposedly brought on by “disaster” and the presence of othered bodies and cultures. Women cannot possibly be viewed human so long our humanity is determined by men’s circumstantial “civilization.” These men are in fact the “disaster zone,” ignoring the very civilized request they treat women and girls as human beings.

Julian Vigo is a scholar, filmmaker, and human rights consultant. Her latest book is Earthquake in Haiti: The Pornography of Poverty and the Politics of Development. Contact her via email: julian.vigo@gmail.com.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 20, 2018 | Rape Culture

Featured image: Transactivist Andi Dier, left, and Rose McGowan.

We claim to be ready for women’s anger, as a society, but we clearly still expect women to express it in ways we are comfortable with.

by Raquel Rosario Sanchez / Feminist Current

One of the first lessons you learn when you do shelter work is that women’s pain and trauma manifests differently from individual to individual. Women are incredibly resilient, but experiencing male violence can lead to months of intense emotional instability or deep depression. Some never recover.

Sometimes victims make decisions you wouldn’t recommend. Sometimes they can be difficult to work with, which can be frustrating. Sometimes they do or say things that you wouldn’t say or do. That is ok. When trying to grapple with the pain and trauma that comes from male violence, it is not your role as a front line worker to prioritize your own feelings and assumptions. You have to understand that it’s not about you, that women will find their own ways to cope, and that the best you can do is to support victims in finding ways to survive, escape, and recover from male violence.

Understanding the impact of male violence on women also means understanding that there is no perfect victim, and that sometimes women speak out or fight back in imperfect ways.

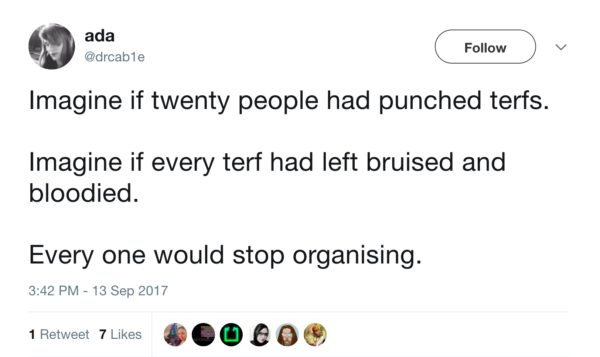

Last month, Rose McGowan’s reading at Barnes and Noble was hijacked by Andi Dier, who identifies as a transwoman and has been accused by multiple women of being a sexual predator. Dier undermined not only McGowan’s experiences of assault and harassment under patriarchy, but the experiences of all women, suggesting that transwomen face more danger than women. Going even further, Dier claimed that women like McGowan were complicit in committing “genocide” against trans-identified people.

In the aftermath, mainstream media coverage and commentary online not only distorted the reality of what happened, but reinforced the myth that there can be such a thing as a perfect rape victim — that there are some victims of male violence who deserve our compassion, and others who do not.

Variety described the incident as “a verbal altercation” and a “heated dispute,” as though McGowan had been walking down the street and got into an argument with a stranger. In truth, Dier admitted to deliberately planning to confront McGowan at her book launch. The media referred to McGowan as “bizarre” and “a white feminist.” Headlines said she “had a meltdown” and described her as “problematic.” Almost every article read as dog whistling, invoking tropes of the “hysteric,” “emotional,” “crazy” woman. The Huffington Post stooped so low as to ask Harvey Weinstein, McGowan’s rapist, for comment on the incident with Dier. Weinstein’s lawyer took the opportunity to reprimand McGowan for “choosing to marginalize a community.”

But how should McGowan have responded? The only appropriate response, according to many, would have been for her to not speak at all and to cede the floor to Dier.

There is something about McGowan standing her ground that is deeply unsettling to many people.

Too many people online have responded by centering what they want from McGowan — as a woman, an activist, a victim, and a survivor. “I want her to be a good ally,” says one twitter user. She is “undeserving” of people’s support, argues another.

We seem to have decided that society is ready for women to be “brave enough to be angry” and that, thanks to the Weinstein scandal, “fury is no longer a cause for shame” in women. But what this incident demonstrates is that, as always, Dier’s fury is justified and coddled while McGowan’s anger becomes a useful alibi for society to ostracize her.

McGowan’s anger has been represented not only as less valid than Dier’s, but as simply wrong. If society truly cared about victims of violence, we wouldn’t impose our expectations on them. And we would understand that a woman like McGowan has every right to be angry at someone who came to her book launch specifically to interrupt and silence her while she is recounting her story of trauma and recovery. Why shouldn’t she be upset?

The subtext of media coverage of the incident reveals that people assume and demand that McGowan should behave in “a proper way.” She went off script, in other words; and commentary shows that people believe that if McGowan changed, she would be worthy, or more deserving of people’s sympathy and support.

Society may have been forced to reckon the ubiquity of male violence, but it is by no means ready to confront the reality of women’s pain and trauma.

There appears to be something more sinister at play, as well. In the backlash against McGowan, I see many people breathing a sigh of relief, as if they are finally able to say, “See, it’s not that we didn’t like her because she was loud and vocal and angry and uncontrollable; the real problem is that she is a TERF/a transphobe/a bad ally.”

It’s the perfect cover for people who prefer their rape victims docile and quiet in their empowerment. In a patriarchy, it is far easier to read about men’s sexual abuse of women when we know the story has a happy ending. It’s easier to digest women’s pain when we learn that it all ended up working out well for her because now she is married and has kids — when we’re told that she got over it and is all better now.

Rose McGowan shatters that “perfect victim” narrative. Not only is she not “over it,” but she refuses to hide or control her anger. She encourages all women to be angry and to use that anger to challenge the system that enables the kind of abuse perpetrated against her.

What happened at McGowan’s book event is not an indictment of her, it’s an exposé of people who present themselves as allies to and supporters of victims of male violence, but who will jump at the chance to tear that same woman down for “acting out of order.” As if there is order in trauma…

What the Barnes and Noble incident reveals is that there are an awful lot of people who were waiting for an opportunity to pounce on women like McGowan and put them back in their place. When the allegations against Harvey Weinstein came out, back in October, McGowan was among the first few actresses to stick her neck out and tell her story of abuse. It is deeply unfair that so many people celebrate superficial demonstrations of empowerment, like wearing white roses or black dresses on the red carpet at award ceremonies (and only once the tide had turned), yet women like McGowan who put everything on the line by speaking out when they were lone voices are sidelined…

We may be ready for women’s anger when it comes in the form of an inspiring Oprah speech at a glamorous awards ceremony, but not in the form of a victim of male violence whose pain is very much still raw and palpable, and who wants people to bear witness to that.

McGowan is not unaware that her honesty is unsettling to many people. On Twitter, she wrote:

“I am unusual, that IS the point. I do not care for formats or traditional thought. Every interview of mine is different, just like a mood. A lot of you are meeting me for the first time. Don’t compare me to what you would do or be. Be free.”

Indeed.

It is not up to the media or the online armchair commentariat to decide whether McGowan “deserves” our support. If your support for victims and survivors of male violence depends on them behaving in a way you consider acceptable, you care more about yourself and your “social justice” persona than about women’s genuine well-being. Women who have been abused by men and dare to speak out deserve better than that.

There is a patriarchy-approved way for women to deal with the trauma of male violence and Rose McGowan is doing it wrong.

More power to her.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 17, 2018 | Prostitution

Featured image: Bridget Perrier speaking at Julie Bindel’s book launch. Image: YouTube. Numerous ex-prostituted women spoke at Julie Bindel’s book launch in London, telling the raw, brutal truth about the sex industry.

by Rahila Gupta / Feminist Current

Prostitution or sex work? Your choice of words gives the game away, marks out where you stand on the issue. Violence against women or just a job? It is a serious battleground for the soul of feminism.

Into this contested territory lands Julie Bindel’s well-researched book, The Pimping of Prostitution: Abolishing the Sex Work Myth. At a time when “sex work” appears to be gaining ground in official circles, Bindel is a passionate abolitionist, meaning she does not believe that decriminalization or legalization can protect prostituted women from the inherent violence of prostitution. As such, she advocates for what’s commonly known as the Nordic Model, in which johns, pimps, and profiteers are criminalized and prostituted women are supported to exit the industry. To date, versions of this model have been adopted by Sweden, Norway, Northern Ireland, Canada, Iceland and France.

Unsurprisingly, the Nordic model is vociferously opposed by those who profit from the sex industry, because it will decrease demand, though they choose to cite concern for the women’s safety instead, saying criminalizing pimps and johns will drive the trade underground. However, as a Swedish police officer quoted in Bindel’s book says:

“How can women in Sweden be in more danger than they were before the law? When all she has to do is pick up the phone, even if [the punter] is rude to her, and we will arrest him because he is already committing a crime.”

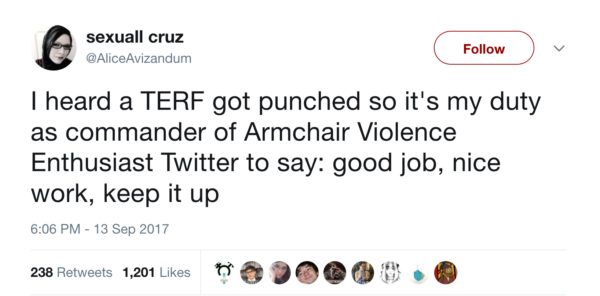

The panel at Bindel’s book launch in London, attended by more than 400 people, featured three women who have exited the sex trade: Sabrinna Valisce from New Zealand; Bridget Perrier, an Indigenous woman from Canada; and Vednita Carter, a black woman from the US. Their testimonies about the reality of the sex industry were moving, but the stuff of nightmares. It was absolutely clear that prostitution is not another job in need of regulation or unionization. It is a distillation of patriarchy in its purest form.

During the panel, Valisce explained that she rejects the term, “sex worker,” because it glosses over the “sucking and fucking” she had to do. She described her daily routine of standing around for 12-17 hour shifts, wearing only lingerie and six-inch heels, waiting to be chosen by men who would come in bellowing, “Which one of you cunts wants to suck my dick?” This was in New Zealand, where prostitution has been decriminalized since 2003, and is held up as a model of good practice by the pro-prostitution lobby, even though women continue to be killed by johns and pimps.

Perrier was lured into prostitution at the age of 12 and stayed for 10 years. The havoc wreaked by men has left her cervix permanently damaged. As a grown woman, she sleeps with her lights on to keep the nightmares at bay. Perrier talked about the racism she experienced in the industry as an Indigenous woman, and how even funeral homes won’t “touch our dead bodies.” “It’s not the laws that kill our women. It’s not the streets that kill our women. It’s the men,” she said.

Perrier founded Sex Trade 101 to support women who want to leave the industry. She said that 98 per cent of the 400 women she has helped wanted to get out of prostitution at some point. The same point was made by Carter, who has worked with 300-500 women each year, for the last 30 years, through her organization Breaking Free. Carter reports that even women who said they “liked” working in the sex trade complained that they were depressed all the time. “It eats at your soul,” she said.

It seems psychologically and politically consistent that so many of those in the abolitionist movement are female survivors who exited the sex trade. Those who continue to work in the industry not only have a vested interest in its growth, but also in bigging it up — especially to its critics. Fiona Broadfoot (who exited at the age of 26 after 11 years of working in the trade) once told me that she used to challenge anyone who dared question her choice of work, but nonetheless would wash herself, inside and out, with Dettol every night. When I asked Bindel if her research confirmed these experiences in the industry, she said she only came across one survivor among the 250 people she interviewed who continued to promote “sex work” as empowering.

While the gap between the pro-prostitution lobby and abolitionists has grown into a chasm, it was not always so. Bindel’s book reminds us that the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP), founded in 1975, were abolitionists in the early days. Their slogan, “For prostitutes, against prostitution” could easily be the tagline for Bindel’s book. They did not argue that sex work is empowering or enjoyable — they saw it as exploitation, as they saw all labour under capitalism.

In recent years, supporters of prostitution have increasingly framed it as a question of choice and women’s agency. Brooke Magnanti — the self-defined “happy hooker” behind the Belle De Jour blog — popularized that narrative; but by all accounts only a tiny percentage of women freely choose and personally profit from it. And it is their voices we hear the most, echoed by their academic supporters and the pimps, whose vested interests it serves, as Bindel has demonstrated. This narrative of “choice” is the poisoned chalice handed down by neoliberalism to feminism. To continue to believe that women freely choose the lives of violent victimization that were laid before us by the panelists at Bindel’s book launch would be grotesque.

This is why I believe that Bindel made an error of judgment in choosing not to devote any space to trafficking. Although she recognizes its importance, in almost the same breath she dismisses trafficking. In a typically memorable Bindel phrase, she says that “sex trafficking is an embarrassment to the pro-prostitution lobby in the same way that lung cancer is to the tobacco industry.” Quite. Trafficking, based as it is on coercion and deception, undercuts the central argument of the sex work lobby, which claims women are exercising their free choice when they enter the industry. Much energy has been expended by these lobbyists in attempting to separate “sex work” from trafficking — the first is presented as harmless and potentially empowering, only the second is accepted as exploitative and harmful. All the while the obvious fact that a thriving sex industry acts as a green light to traffickers is ignored.

Although the statistics are unreliable and heavily contested, trends show that more and more migrant women are being prostituted in the West. A 2009 studyfound that in a majority of European countries up to 70 per cent of women in the industry were migrant women. While not all of them will be trafficked, this is a telling statistic — it demonstrates the unequal economic desperation of migrant versus local women.

Bindel describes trafficking as “international pimping” and believes “that the only difference between international and local pimping is that some women are pimped across borders, and others are not.” But from the phrase “across borders,” a whole series of vulnerabilities flow, as I argued in my book Enslaved. Most notably, not being able to access the protection of the state, such as it is, and living in the shadow of imminent deportation.

Both lobbies acknowledge it is important to tackle the factors which drive women into prostitution, like poverty. It is no surprise that, as Valisce explained, even when women choose to leave, they can spend years exiting and re-entering the industry because of the difficulties of finding work elsewhere.

As long as women are trapped in these situations, we must focus on exit strategies, while also supporting policies that will ensure that women’s health and safety needs are met and that they can live as free from abuse as possible.

Rahila Gupta is a freelance journalist, writer, activist and longstanding member of Southall Black Sisters. She is author and editor of several books, and is currently collaborating with Beatrix Campbell on a book titled, “Why Doesn’t Patriarchy Die?” which will investigate how patriarchy fits with diverse political systems.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 30, 2017 | Gender

Featured image: Crosses marking the mass grave of femicide victims in Chihuahua (Wikipedia)

by Raquel Rosario Sanchez / Feminist Current

These are hard times for women. The feminist movement of the 70s and 80s raised awareness about violence against women on a global scale. As a result, today, we are able to identify the murder of women and girls as systemic under patriarchy. In Latin America and the Caribbean, where violence against women is an epidemic, we even have a term for this: femicide (or “feminicidio’” in Spanish), meaning, “the murder of women on account of their sex.”

Despite this, women’s lived reality has become unspeakable today. Those who acknowledge that females are oppressed as a class, under patriarchy, are labeled phobic and worse. In other words, feminist analysis of systems of power is set aside in order to accommodate the idea that womanhood is nothing more than a “feeling.”

Over at Equality For Her, journalist Katelyn Burns writes:

“So what does it mean to feel like a woman? It means that if you are a woman, it’s whatever you are currently feeling. Women are so diverse in their experiences that there can be no universal model of womanhood.”

Apparently, womanhood is now so all-encompassing it can be experienced by anyone, based on “feelings.” Yet, at the same time, within this analysis, womanhood is rendered meaningless and without structural roots.

“What is a woman?” is a question asked by those privileged enough to never have had to suffer the answer to this question. No one asks women what womanhood “feels” like, because, for us, being “women” is simply our reality. Most womenaround the world learn early on that, under patriarchy, their opinions about their subordination are irrelevant. As a structural force, patriarchy continues to degrade and violate women and girls, whether we like it or not, whether we agree with it or not — women’s feelings be damned.

Male violence against women ensures our compliance. Femicide is the lethal extreme of this, but violence against women and girls manifests in a myriad of ways. In feminist circles, we talk about male violence against women often. Indeed, ending male violence is the most pressing point in the agenda for women’s liberation. But how can we eradicate male violence against women if we ignore the centrality of women’s bodies under male supremacy? How can we move beyond a patriarchal society if we refuse to acknowledge that women are a class of people, whose status is determined by their sex?

On August 31st, this reality was laid bare in a Chinese hospital. A 26-year-old woman named Ma Rongrong started labour a week ahead of schedule. She was advised by the medical team at the Yulin Number 1 hospital, in the Shaanxi province, that the girth of her baby’s head was too big for her to give birth naturally. Ma and her husband, Yan Zhuangzhuang, signed a document, against medical recommendations, stating that Ma still wanted to try a vaginal birth.

The Chinese newspaper Caixin reports that, as the labour pains intensified, Rongrong changed her mind and requested a cesarean section, multiple times. The problem was that, under Chinese law, a patient’s family must approve of all major surgeries their relative is to undergo. Rongrong’s family denied her the c-section.

The article explains: “Hospital records showed that both the woman and the hospital requested permission from the family three times to perform the operation, but her relatives allegedly refused and insisted on a natural delivery.” There’s video footage of Rongrong trying to walk, but kneeling in excruciating pain, surrounded by half a dozen family members.

Today, the family and the hospital staff blame each other for denying Rongrong the c-section she needed. But it seems that the last word laid with her family — specifically Rongrong’s husband, who had her written permission to decide on the method of medical treatment for his wife (after consultation with medical staff), but who still didn’t approve the surgery.

In her desperation, Rongrong even tried to leave the hospital, but was caught and brought back inside. Eventually, she made a drastic and tragic decision: Ma climbed out of a window on the fifth floor, and jumped to her death.

Why did Rongrong die? I’d argue that Rongrong died, ultimately, because of her sex.

Nobody asked Rongrong if she “felt” like a woman, patriarchy simply treated her as one — governing her female body against her will, ignoring her thoughts and feelings. A nationwide policy dictating that all surgeries have to be approve by family members affects every patient in China. But, as Rongrong’s death shows, this policy has particular repercussions for those with female bodies.

A similarly gruesome case took place around the same time in the Dominican Republic. A 16-year-old girl named Emely Peguero Polanco had been missing for over 10 days. Her disappearance and the search efforts were breaking news, in part because Peguero Polanco was five months pregnant in a country that fetishizes pregnancy. For almost two weeks, it seemed the country could talk of little else.

As many people suspected, Peguero Polanco had been murdered. Her final hours and the manner of her death were ghastly. She had been ambushed by her boyfriend, an older guy named Marlon Martinez, who told her he would take her to a doctor’s appointment. Instead, he took her to his apartment where he (probably with the aid of other people) performed a forced abortion on her.

The investigation is still open but the crime is both misogynistic and vile. Marlon’s mother, Marlin Martinez, was an influential politician in the community and actively helped her son cover up the crime. Marlin paid multiple employees to move Peguero Polanco’s body around the country so that the authorities couldn’t find it. Marlin even appeared with her son in a video recording where they pled with Peguero Polanco — who had already been murdered — to return to her loved ones, addressing her as though she were a runaway.

The forensic report states that Peguero Polanco was a victim of psychological and physical violence, as well as torture and barbaric acts:

“Inside the cadaver, there were pieces of the fetus that she was carrying in her womb, concussion to the uterine wall and vaginal canal, a perforation of the uterus, meaning that great force was applied in the area and various organs relating to a forced abortion.”

The report also explains that she had “a blunt concussion with cerebral hemorrhaging, meaning the trauma was inflicted while she was alive.”

Regardless of the “motives” her murderer and his accomplices might have had (some analysts argue that there was a class element because Peguero Polanco was poor and Marlon was upper class, so his family didn’t want a working class girl carrying his child), Peguero Polanco was killed because of her pregnant, female body. And I am certain that none of those who performed the forced abortion that killed her asked Peguero Polanco if she “identified” with the biological realities of her womanhood.

Rongrong and Peguero Polanco are merely two recent examples, but the ways in which women are killed because they are women, under a patriarchal system, are infinite. But today’s queer theory and its advocates are casting aside this brutal reality in order to depict womanhood as abstract. Reducing “womanhood” to feelings, clothing, and personal identities is a slap in the face to most women and girls whose oppression is forced on them, regardless of how they dress or identify.

Recently, British singer Sam Smith came out as “non-binary,” saying, “I feel just as much woman as I am man.” This newfound identity appears to be based solely on the superficial. He explains:

“There was one moment in my life where I didn’t own a piece of male clothing, really… I would wear full makeup every day in school, eyelashes, leggings with Dr. Martens, and huge fur coats — for two and a half years.”

Determining that you “feel like a woman” because you like to wear high heels, makeup, and dresses is deeply misogynistic, as these are merely the trappings of femininity — a projection of male fantasies about women — yet this idea appears to be gaining traction.

Much like the upper class loves the aesthetic of the working class and similar to the way male authors fetishize women in the sex trade, hoping to appear “hip,” as Kajsa Ekis Ekman argues, this watering down of womanhood is a form of gentrification. In this case, womanhood is desired and coopted by those who benefit under patriarchy (males), while the uncomfortable and violent realities of womanhood remain relegated to the underclass, who don’t have a way out.

In Being and Being Bought, Ekman writes:

“A man who romanticizes the working class applauds the physical labourer and hopes that he has some of those attributes, but it is stereotypical masculinity he admires, not a living person trying to survive under difficult conditions. The ‘wigger’ feels like he is part of the black community, but is not upset about violence in the ghetto. What he fails to understand is that by fetishizing someone’s everyday life, he shows how distant he is from it. Living conditions become and identity, and then a fetish.”

The gentrification of womanhood takes the gender stereotypes forced on women and presents them as though they define womanhood. This offers a subversive facade that functions only on an individual level, rather than a structural one, ignoring the suffering and oppression of women. Rather than advancing the rights of women and girls, this form of gentrification obscures them, erasing the reasons women need sex-based rights in the first place.

Ekman argues:

“The oppressed is keenly aware of the humanity of the privileged. For the privileged, on the other hand, the oppressed is an enigma living in a magical, half-human world. The fantasy of the privileged is having the ability to wallow in this world.”

Indeed, men may wallow, but they will never be forced to exist within the constraints of womanhood, as they were not born with female bodies. Through superficial choices like clothing and make-up, women’s oppression is transformed into something liberating… For everyone but us.

The casual cruelty of these nonsensical, circular arguments is playing out while girls and women around the world bear the brunt of what, for them, is a reality, not an identity.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 23, 2017 | Male Violence

by Meghan Murphy / Feminist Current

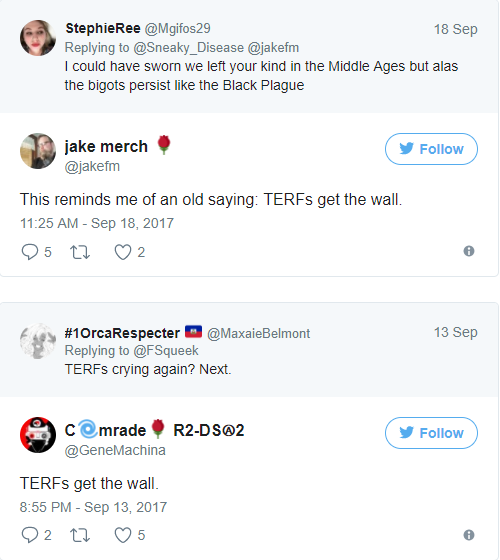

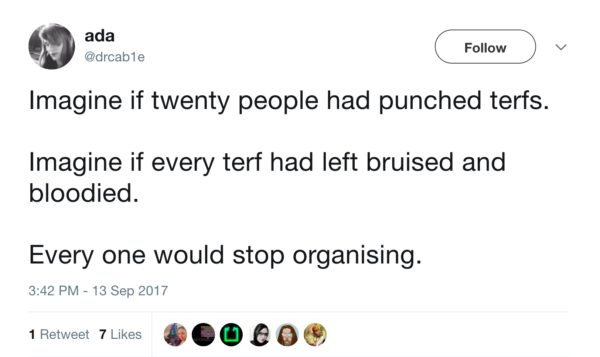

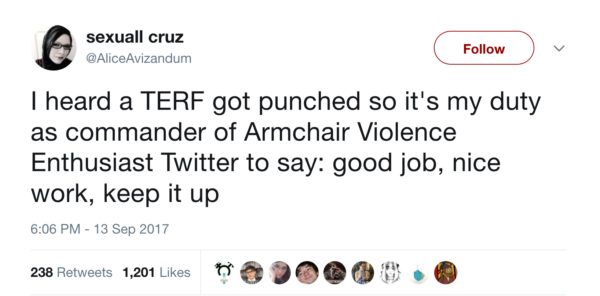

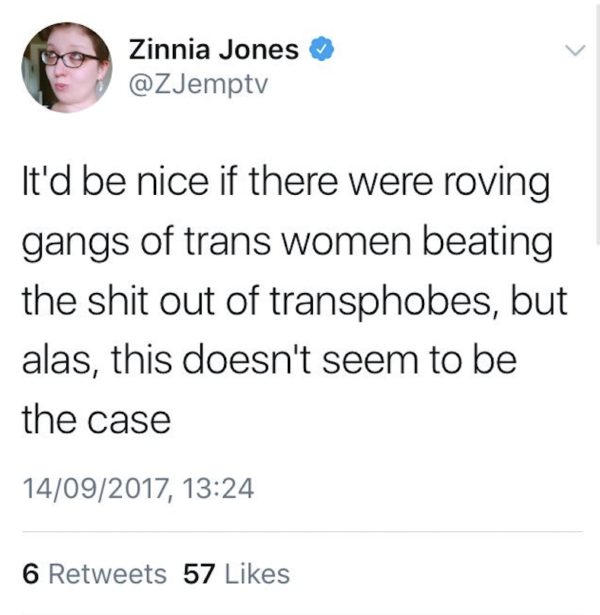

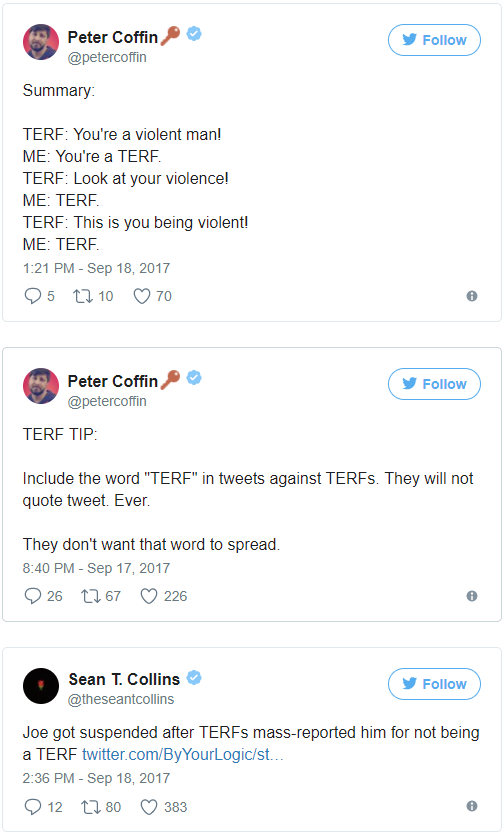

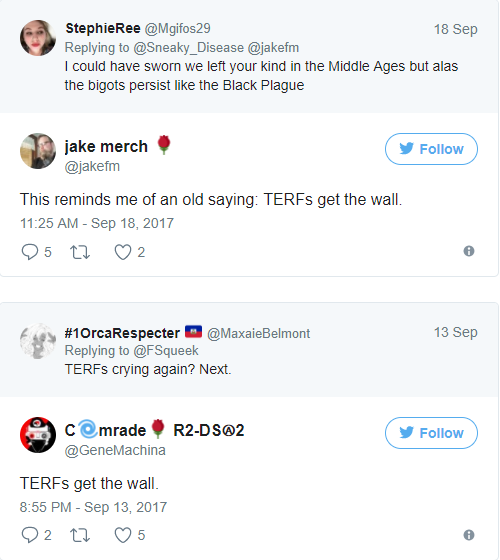

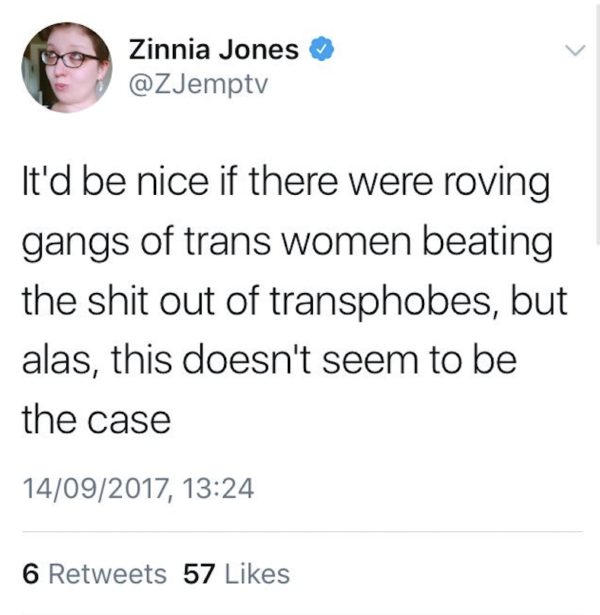

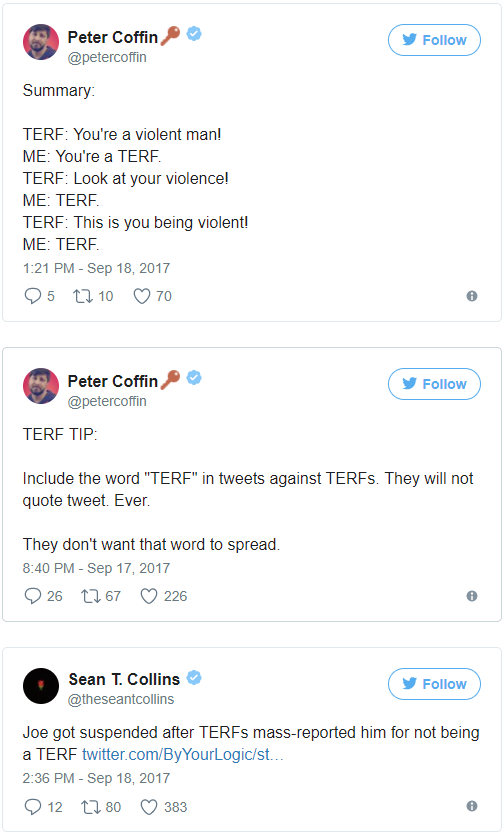

Last week, a 60-year-old woman was beaten up at Speaker’s Corner by several men. She was there with a group of women, who had chosen the historic corner of Hyde Park as a meeting place, before heading off to a talk called, “What is Gender.” The men who punched and kicked Maria MacLachlan had come to protest the women on account of their interest in feminism and in discussing the way new conversations and legislation around “gender identity” could impact the women’s movement and women’s rights. The protestors did not frame their anger and inflammatory rhetoric in this way, though. Instead, they labelled the women “TERFs” (trans exclusionary radical feminists) — a word that has come to signify a modern witch: to be silenced, threatened, harassed, punched, and — yes — killed.

The idea that feminists who question the notion of “gender identity” should be beaten and murdered has very rapidly become accepted by self-described leftists. We’re not just talking about Twitter eggs, here. Men with large platforms who are publicly associated with Antifa and groups like the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) have amplified the “punch TERFs” and “TERFs get the guillotine” message proudly, with the support of their comrades. In reference to The Handmaid’s Tale, many have taken to saying “TERFs get the wall.”

The comparison is a surprisingly (and frighteningly) truthful admission in terms of the intent of these men. “The wall” in The Handmaid’s Tale is where executed bodies are hung, often with placards around their necks that read “Gender Treachery.” The dead bodies serve as a warning to others: do not rebel, do not fight back, do not reject the patriarchal order of things. And this is precisely what these men who use the term “TERF” are saying to women: obey our rule or you will be punished.

Rather than condemning the violence at Speaker’s Corner, numerous trans activists and self-identified leftist men have celebrated and encouraged it.

While some will claim the word “TERF” is neutral, it’s use demonstrates the opposite. It is not a word that women have claimed for themselves — like “slut,” “cunt,” or “bitch,” “TERF” is a word imposed on women to shut them up, bully them, condemn them, smear them, humiliate them, and dismiss them. But more than that: it is a threat. If I think about the times in my life I have been called these words — cunt, bitch, slut — by a man, I have almost always felt the threat of violence behind them. The spitting rage behind those words — the desire to follow through with a punch — is too often present. I have always known these words are used against me as an explicit reminder: you are subordinate. No matter how confident, tough, self-assured, strong, or brave a woman is, these words still put her in her place.

The term, “TERF,” is itself is an intentional manipulation, intended to reframe feminist ideas and activism as “exclusionary,” rather than foundational to the women’s liberation movement. In other words, it is an attack on women-centered political organizing and the basic theory that underpins feminist analysis of patriarchy.

For example, those of us called “TERF” are labelled as such for numerous crimes, including:

- Understanding that women are members of an oppressed class of people (a sex class or caste, as feminists like Kate Millett and Sheila Jeffreys have called it)

- Challenging the notion of innate or internal gender

- Having conversations about “gender identity”

- Questioning whether or not children should begin the process of transitioning

- Associating with or defending women who have been labelled “TERF”

- Understanding that the root of women’s oppression and male supremacy is in biological sex

- Understanding that gender is imposed, and is oppressive/exists to create a hierarchy between men and women.

- Questioning dogma and mantras like “transwomen are women”

- Supporting woman-only space

- Disputing an ideology that claims “male” and “female” are not a material reality

These things are not only not criminal, but are at the root of feminism. In other words, in order to understand how patriarchy works, you must first understand who is a member of the dominant class and who is a member of the subordinate class. You must understand that male violence against women is systemic. You must understand that women are not inherently “feminine,” and that men are not inherently “masculine.” You must be willing to have critical conversations and ask challenging questions about the status quo, about dominant ideology, and about political discourse. You must understand that patriarchy began as a means to control women’s reproductive capacity, and that, therefore, women’s biology is very much central to their status as “less than.” You must understand that feminism is a woman-centered movement, and that women have the right to meet and to organize amongst themselves, without members of the oppressor class (men), to advocate toward their own liberation.

What people are saying when they say “TERF” is “feminist.” It is “uppity woman.” What they mean when they say “exclusionary” is not, as is often claimed, “exclusive of trans-identified people,” but “exclusive of males.” Gender non-conformity is welcomed in feminism — feminism is about not conforming to gender norms. If we were interested in conforming, we would, as is often suggested to us, sit down and shut up.

While “TERF” has always been a slur, what has become clear of late is that it is no longer just that: it is hate speech.

Deborah Cameron, a feminist linguist and professor in language and communication at Oxford, explains that there are key questions we must ask to determine whether a term constitutes a slur, such as:

- Has the term been imposed or has it been adopted voluntarily by the group the term has been applied to?

- Is the word commonly understood to convey hatred or contempt?

- Does the word have a neutral counterpart which denotes the same group without conveying hatred/contempt?

- Do the people the word is applied to regard it as a slur?

Considering the answers to these questions — that, yes, the term has been imposed on feminists, it is always understood as pejorative, it does have a neutral counterpart (i.e. one could just use the term “feminist”), and feminists have consistently stated that the term is a slur — “TERF” is undoubtedly that. Considering that women are the primary target of this slur and that it is commonly attached to threats of (and, as of late, real-life) violence, there is something more we must now contend with.

Following the violent incident at Speaker’s Corner (which was no accident — one of the perpetrators had publicly expressed his intention to “fuck some terfs up”), I have received hundreds of death threats from men online. I’m not alone, either. Any woman who challenged men’s celebration or defense of the violence at Speaker’s Corner became a target. All of these threats have been attached to the term, “TERF.” Feminists have been labelled in this way specifically to dehumanizethem, to spread outrageous lies about their politics (claiming feminists want to kill trans-identified people or that they advocate genocide), to reframe them as oppressors of males who identify as gender non-conforming, and to paint them, generally, as evil witches, therefore deserving of violence.

Proliferating lies about and dehumanizing an oppressed group of people in order to justify abuse is a longtime strategy of racists and xenophobes. Hitler used these tools to commit genocide against the Jews. Indeed, propaganda was a key tool of the Nazis in their efforts to spread antisemitism, quell dissent, and turn people against one another. German newspapers printed cartoons and ads depicting antisemitic images and messages.

“If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it,” was Hilter’s guiding mantra. He trusted that people wouldn’t think for themselves and would simply act out of fear or intellectual laziness, jumping on bandwagons without thoroughly questioning the purpose and foundation of those bandwagons. The Holocaust was successful because the public went along with it — because individuals believed the myths and lies proliferated by the Nazis, and because they didn’t stand up, think critically, or push back.

While hate speech laws differ from place to place (and can be blurry), as a general rule, making statements intended to expose people to hatred or violence, or that advocate genocide, constitute hate speech.

Because feminists who challenge gender identity ideology are often (strategically) accused of advocating genocide, let’s be clear: “genocide” does not mean arguing that biological sex is a real thing, challenging the idea that femininity and masculinity are innate, or suggesting certain spaces should be for women and girls alone. What genocide does mean is: killing members of an identifiable group or deliberately inflicting conditions of life aimed to bring about the physical destruction of an identifiable group.

In other words, suggesting that feminists should all be destroyed, fired from their jobs, forced into homelessness, harassed, silenced, removed from society, abused, and sent to the Gulag.

Under the law, advocating or promoting genocide is an indictable offence. Likewise, those who promote hatred against an identifiable group or communicate statements in public that incite hatred or violence against an identifiable group that are likely to lead to a breach of the peace (i.e. for example: what happened at Speaker’s Corner) are guilty of an indictable offence.

But these laws are hard to enforce. Which is not necessarily a bad thing. We should not be charging people willy-nilly for things they say on Twitter. What we most certainly should be doing is holding men to account for inciting violence against women and holding media and other institutions to account for normalizing hate speech.

So, beyond the law, let’s talk about accountability. When the media normalizes hate speech, they become culpable. A publication would not use the n-word to describe a black person or the word “kike” to describe a Jewish person. This is because we know that these terms reinforce racism and justify discrimination and/or abuse against particular groups of people who have been historically and systemically oppressed. When the media, institutions, and authorities become aware that a particular term is being used to incite violence against women, it is their responsibility to condemn or simply refrain from encouraging the use of that language.

And yet we have seen various media outlets using the term uncritically, of late.

The fact that the vast majority of those connecting the word “TERF” to threats of violence, death, and genocide are men is notable. The word has been offered up to those who identify as leftists, who have been, on some level, prevented from making misogynistic statements publicly or otherwise advocating violence against women. Their “progressive” credentials meant that they had to maintain a facade of political correctness. But because women labelled “TERF” have been compared to Nazis and bigots, and because trans activism claims to be allied with the interests of the marginalized (despite its overt anti-feminism and individualist ideology), these leftist men have a socially acceptable excuse. Indeed, they seem to revel in it. It’s as if they were given the green light to scream “bitch” (or perhaps “witch” would be more accurate, considering the targeting of specific unruly women to “punch”… or burn…) over and over again, cheered on by their comrades.

If “TERF” were a term that conveyed something purposeful, accurate, or useful, beyond simply smearing, silencing, insulting, discriminating against, or inciting violence, it could perhaps be considered neutral or harmless. But because the term itself is politically dishonest and misrepresentative, and because its intent is to vilify, disparage, and intimidate, as well as to incite and justify violence against women, it is dangerous and indeed qualifies as a form of hate speech. While women have tried to point out that this would be the end result of “TERF” before, they were, as usual, dismissed. We now have undeniable proof that painting women with this brush leads to real, physical violence. If you didn’t believe us before, you now have no excuse.

Where these fairs concerned women, the stories were always the same: kidnapping, sexual slavery, freak shows, then death. Sarah Baartman was taken from the Gamtoos Valley in the Eastern part of the Cape Colony (present-day South Africa) and brought to England in 1810. Bought and sold from handler to handler and shown at various fairs in England and Ireland, she was exhibited as part of a freak show under the name “Hottentot Venus.” Finally, in 1814, she was brought to the Palais Royal in Paris where she was enslaved and became the object of scientific study.

Where these fairs concerned women, the stories were always the same: kidnapping, sexual slavery, freak shows, then death. Sarah Baartman was taken from the Gamtoos Valley in the Eastern part of the Cape Colony (present-day South Africa) and brought to England in 1810. Bought and sold from handler to handler and shown at various fairs in England and Ireland, she was exhibited as part of a freak show under the name “Hottentot Venus.” Finally, in 1814, she was brought to the Palais Royal in Paris where she was enslaved and became the object of scientific study.