by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 29, 2016 | Rape Culture, Repression at Home

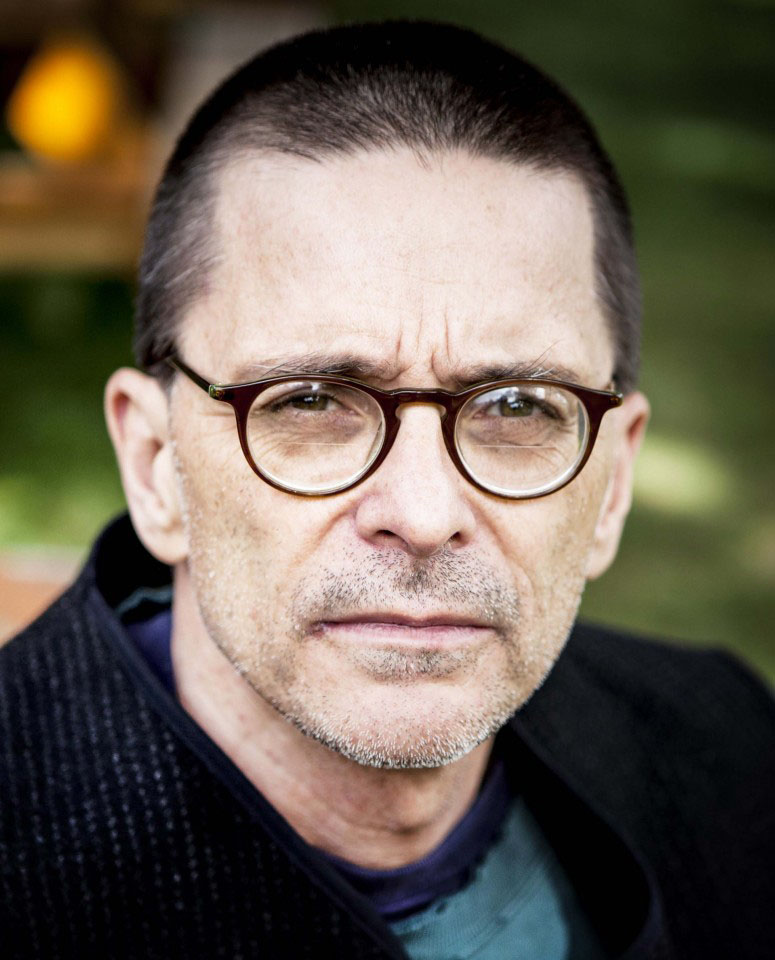

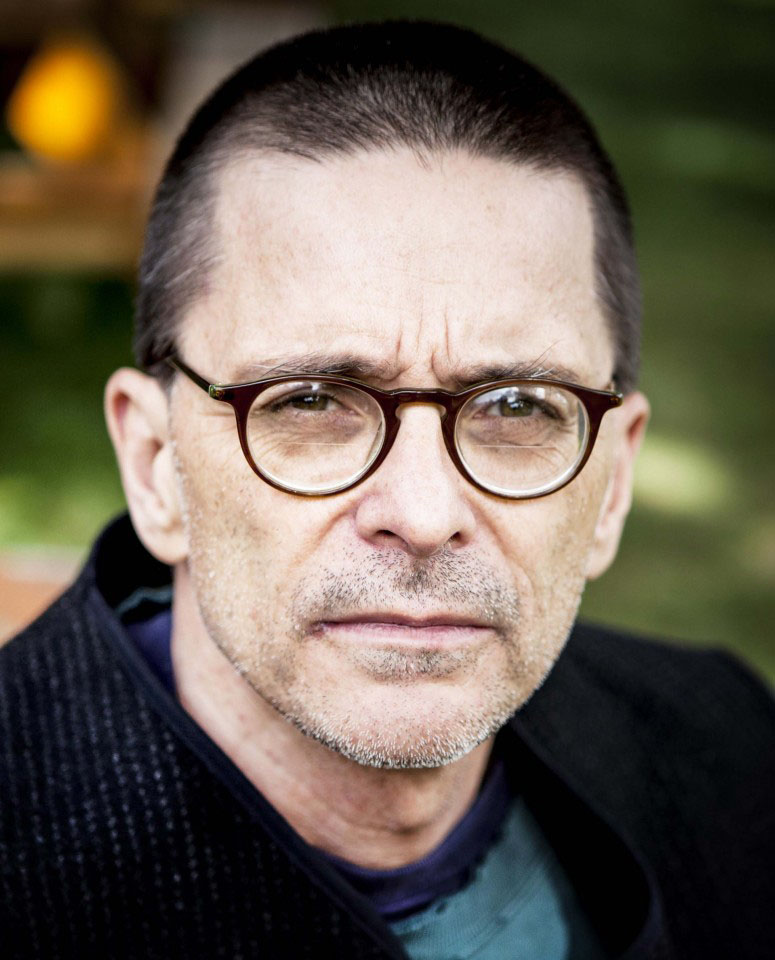

by Robert Jensen

From a “critique” of my work on the latest Professor Watchlist, I learned that I’m a threat to my students for contending that we won’t end men’s violence against women “if we do not address the toxic notions about masculinity in patriarchy … rooted in control, conquest, aggression.”

That quote is the “evidence” that I am one of those college professors “who discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values, and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom,” according to the watchlist’s mission statement.

This rather thin accusation appears to flow from my published work instead of an evaluation of my teaching, which confuses a teacher’s role in public with the classroom. So, I’ll help out the watchlist and describe how I address these issues at the University of Texas at Austin, where I’m finishing my 25th year of teaching. Readers can judge the threat level for themselves.

I just completed a unit on the feminist critique of the contemporary pornography industry in my course “Freedom: Philosophy, History, Law.” We began the semester with On Liberty by John Stuart Mill (I’ll assume the Professor Watchlist approves of that classic book), examining how various philosophers have conceptualized freedom. We then studied how the term has been defined and deployed politically throughout U.S. history, ending with questions about how living in a society saturated with sexually explicit material affects our understanding of freedom. I provided context about feminist intellectual and political projects of the past half-century, including the feminist critique of men’s violence and of mass media’s role in the sexual abuse and exploitation of women in a society based on institutionalized male dominance (that is, patriarchy).

The revelations about Donald Trump’s sexual behavior during the campaign provided a “teachable moment” that I didn’t think should be ignored. I began that particular lecture, a week after the election, by emphasizing that my job was not to tell students how to act in the world but to help them understand the world in which they make choices.

Toward that goal, I pointed out that we have a president-elect who has bragged about being sexually aggressive and treating women like sexual objects, and that several women have testified about behavior that—depending on one’s evaluation of the evidence—could constitute sexual assault. Does is seem fair, I asked the class, to describe him as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

Trump sometimes responded by contending that Bill Clinton was even worse. Citing someone else’s bad behavior to avoid accountability is a weak defense (most people learn that as children), and of course Trump wasn’t running against Bill, but we can learn from examining the claim.

As president, Bill Clinton abused his authority by having sex with a younger woman who was first an intern and then a junior employee. He settled a sexual harassment lawsuit out of court, and he has been accused of rape. Does it seem fair to describe Bill Clinton as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

So, we live in a world in which a former president, a Democrat, has been a sexual predator, yet he continues to be treated as a respected statesman and philanthropist. Our next president, a Republican, was elected with the nearly universal understanding that he has been a sexual predator. How can we make sense of this? A feminist critique of toxic conceptions of masculinity and men’s sexual exploitation of women in patriarchy seems like a good place to start.

In that class, I spent considerable time reminding students that I didn’t expect them all to come to the same conclusions but that they all should consider relevant arguments in forming judgments. I repeated often my favorite phrase in teaching: “Reasonable people can disagree.” Student reactions to this unit of the class varied, but no one suggested that the feminist critique offered nothing of value in understanding our society.

Is presenting a feminist framework to analyze a violent and pornographic culture politicizing the classroom, as the watchlist implies? If that’s the case, then the decision not to present a feminist framework also politicizes the classroom, in a different direction. The question isn’t whether professors will make such choices—that’s inevitable, given the nature of university teaching—but how we defend our intellectual work (with evidence and reasoned argument, I hope) and how we present the material to students (encouraging critical reflection).

If the folks who compiled the watchlist had presented any evidence that I was teaching irresponsibly, I would take the challenge seriously. At least in my case, the watchlist didn’t. But rather than assign a failing grade, I’ll be charitable and give the project an incomplete, with an opportunity to turn in better work in the future.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men, to be published in January by Spinifex Press. Other articles are online at http://robertwjensen.org/. He can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu.

by DGR News Service | Oct 16, 2016 | Rape Culture

Society must choose whether women count as human

Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

Feminism has always been a contested area of politics. Fierce arguments centre on what it is, and why we need it. The best definition I know is from Andrea Dworkin: “Feminism is the political practice of fighting male supremacy on behalf of women as a class.” In one elegant sentence, she names both the problem ― male supremacy ― and the solution ― political action.

Implicit in those 16 words are also the two requirements of the human heart: love and hope. It is an act of love to notice women. Women are on display everywhere of course ― naked, for sale, the coin of the realm in a pornographic culture ― but being an object is the opposite of being human. Noticing the harm that is being done ― insisting that it is harm ― starts from love.

Such noticing tends to have an inverse relationship to hope. When harms against a people are both vicious and everyday, hope becomes a combat discipline. But, whether grim or glad, hope is possible only because change is possible. This is the promise of feminism: as endless as the horrors seem, they could end. We, as a society, could end them.

Armed with love and hope, I travelled to London recently for a conference on male violence and how we might end it. I left the US still braced against the details that had come out of Ohio: three women, one six-year-old girl, a basement strung with chains ten years long.

I arrived in London to news of Mark Bridger’s trial: his catalogue of images of murdered girls, his library of sadistic child-porn, the stalking that escalated from online to real life. This meant real death to a perfect promise of a girl named after spring. Her parents are now condemned to a deep winter of grief; how they will survive is anyone’s guess.

Then there was the long fall of Chevonea Kendall-Bryan, the 13-year-old who fell to her death from the window of her home, having suffered sexual bullying. Longer still was the fall from human to object, through rape, and more rape, landing finally on the unyielding surface of complete public violation. Does it matter whether she jumped or fell? Her life was shattered either way.

This is where we stand or fall as a society. We will have to choose. Right now, our society is choosing to make cruelty normal. We are choosing saturation in sadism. The choice turns on whether women count as human.

A few brute facts will answer. Globally, one in three women will be raped or beaten in her lifetime. Half of all sexual assaults are committed on girls under 16: might as well start the lesson early. In the UK, a woman is raped every nine minutes. There are plenty more numbers, and inside each and every one are the broken shards where body and soul, self and world, once met.

The numbers should speak for themselves, but numbers don’t actually speak, of course. They need human voices to carry them. The result of subordination, though, is always silence. Silence is what happens when people are turned into objects. Violence will do that. Sexual violence especially will do that. Sexual violence against children is a shroud of silence that can take a lifetime to unwind.

Amnesty International reports that rape is the most traumatic form of torture. In fact, women who have survived prostitution have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder than soldiers who have survived combat, which is to say that the war men are waging against women is in many ways worse than the wars they inflict on each other.

If you need convincing, type the word “rape” into Google images. Or, if you have the stomach and the spiritual stamina, try “torture porn”. What you will see is not entertainment, or sex, or freedom. What you will see is hell. What you will also see is that men by the million have been there before you.

We need feminism because, without it, the realities of women’s lives are unspeakable ― each woman cut adrift in a hostile, chaotic sea. Apply feminism, and that chaos snaps into a sharp pattern of subordination ― from the small, daily insults to body and soul, to the shattering traumas of incest and rape.

The crimes that men commit against women are not done to women as random individuals: they are done because women belong to a subordinate class, and they are done to keep women a subordinate class.

None of this will change unless we face the truth. I wrote above that every nine minutes a woman is raped. That is hard enough, but it is not the truth. This is: every nine minutes a man rapes a woman. And I am left with a human howl of “Why?” After 30 years spent fighting male violence and pornography, I still have no answer.

I am a feminist because I think women count as human. But feminism also insists on the humanity of men: we think that men can do better. The anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday studied 95 societies, and found that almost half were rape-free. It is not random. It is actually rather straightforward. Rape-free cultures value co-operation whereas rape-prone cultures reward competition. In the former, political and economic power are shared by the sexes; in the latter, women are dispossessed.

Whereas in the one, the sacred has both female and male aspects, in the other, God is only ever male. And now we come to it: in rape-free cultures, anyone can assume positions of ceremonial importance. In rape-prone cultures, men exclude women from roles of spiritual intercession.

Social subordination is like a set of concentric circles. The innermost is where the worst occurs: the cattle cars, the severed limbs, the missing girls found as bone fragments and blood stains. But every circle in the set helps to constrain the people trapped inside. The outer rings shore up the inner horrors, making them both normal and invisible.

How can such things happen, we ask in anguish? They can happen because each successive circle ― each institution and social practice ― creates the bull’s eye where Chevonea landed and April will never be found.

We have a choice, as individual men and women, and as a society. We can keep other humans barricaded inside such atrocities, or we can bring those barricades down. Either women will finally count as human, or the rancid pleasures of sadism will continue to rot our society and our souis. Choose now, before another girl falls, and another goes missing.

Originally published in the June 28, 2013 issue of Church Times

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 12, 2016 | Male Violence, Rape Culture

Quechua Bolivian woman unfairly sentenced to life in Argentina

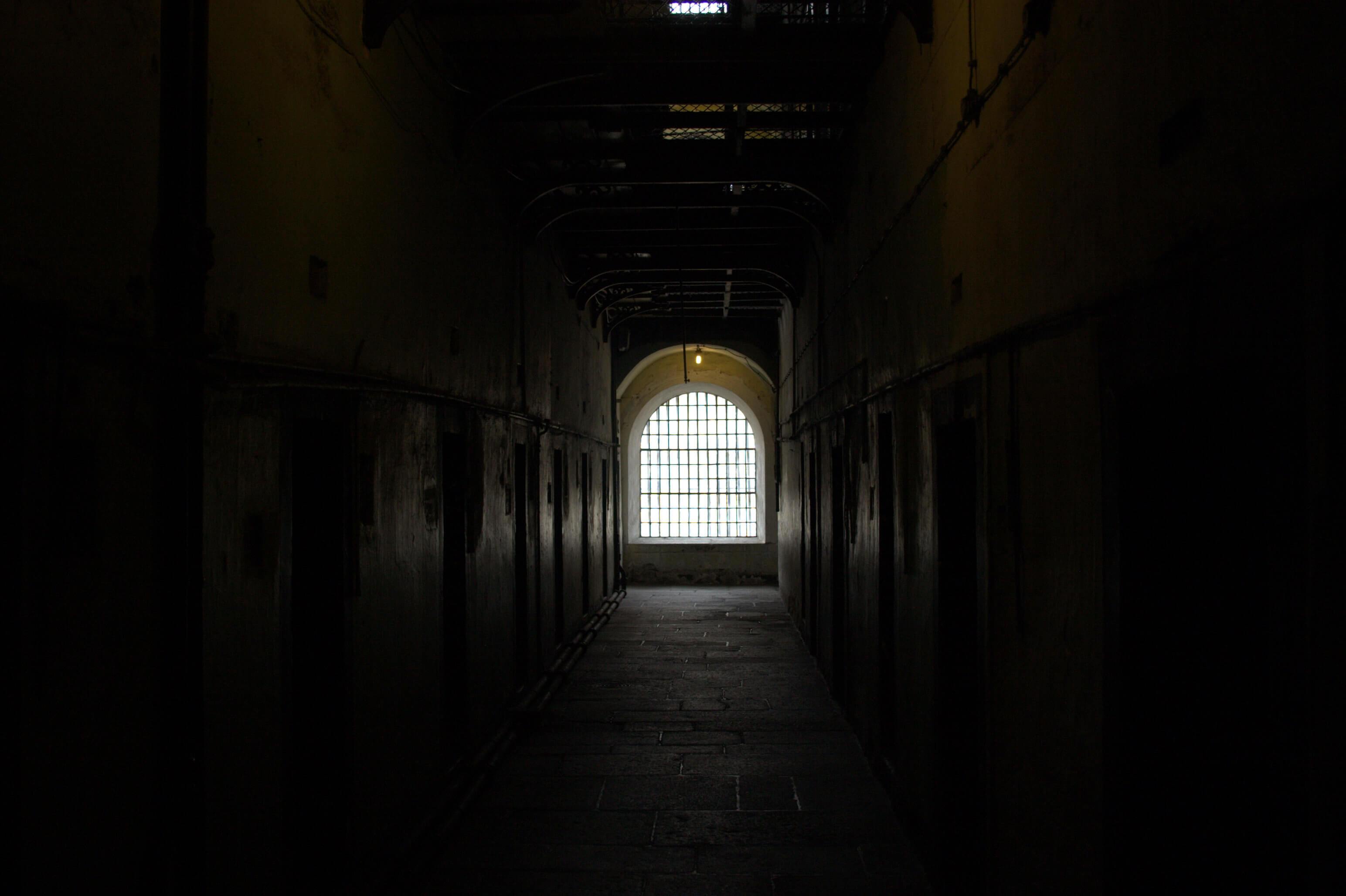

Reina Maraz Bejarano was the last person in the courtroom to understand that she had just been sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly murdering her husband.

Maraz is from an indigenous community in Bolivia. Like many women in rural Bolivian communities, she was raised speaking the local language, not Spanish. On the day she was sentenced by the Argentine justice system, Maraz’s interpreter was translating the judges’ words from Spanish into Quechua so that she could understand. Married at 17 years old, a mother shortly after and subject to a violent marriage, Maraz was 22 when she was arrested for the murder of her husband Limber Santos. She was 26 in November 2014, when her future was determined by three Argentine judges. At that point she had already been imprisoned for four years. Because she couldn’t fully understand Spanish, she spent nearly a year of that jail time without understanding that she was accused of being responsible for her husband’s death.

Maraz’s case is emblematic of the ways in which both the dominant culture and the judicial system abuse women, especially indigenous women. For Maraz, this means being a survivor of physical and psychological violence. Then came the double injustice of being blamed for that violence by the Argentine state. Now she is a victim of a judicial system gone wrong.

A Long Path of Migration and Violence

To tell the story of how Maraz was condemned to life in Argentina’s prisons that day in court in 2014, we have to rewind to 2009, the year Maraz came to Argentina with her husband Limber Santos and their two young boys.

There are more undocumented Bolivian immigrants in Argentina than in any of Bolivia’s major cities. Many migrate from rural areas like Santos’ community in Chuquisaca, Bolivia, and often whole families move. In Maraz’s case she had no choice: her husband threatened to take away their children if she did not accompany him to Argentina.

Maraz testified in court that when they lived together in Bolivia her husband used to get drunk and beat her. Once they were in Argentina, the abuse continued. His family was complicit in the physical violence and took away Maraz’s documents.

After some months in Argentina, the Santos-Maraz family eventually settled in cramped rooms at a brick kiln where they worked in the city of Florencia Varela, in greater Buenos Aires. In a 2013 interview conducted in jail, Maraz’s interpreter translated her words, “Her children never went to school because her husband didn’t want them to. Reina was unhappy, there was never enough money because of Limber’s drinking.”

Santos was going on drinking sessions in the Buenos Aires barrio of Liniers with a man who worked and lived in the kiln also, Tito Vilca Ortiz. Vilca was to play an important role in what happened next.

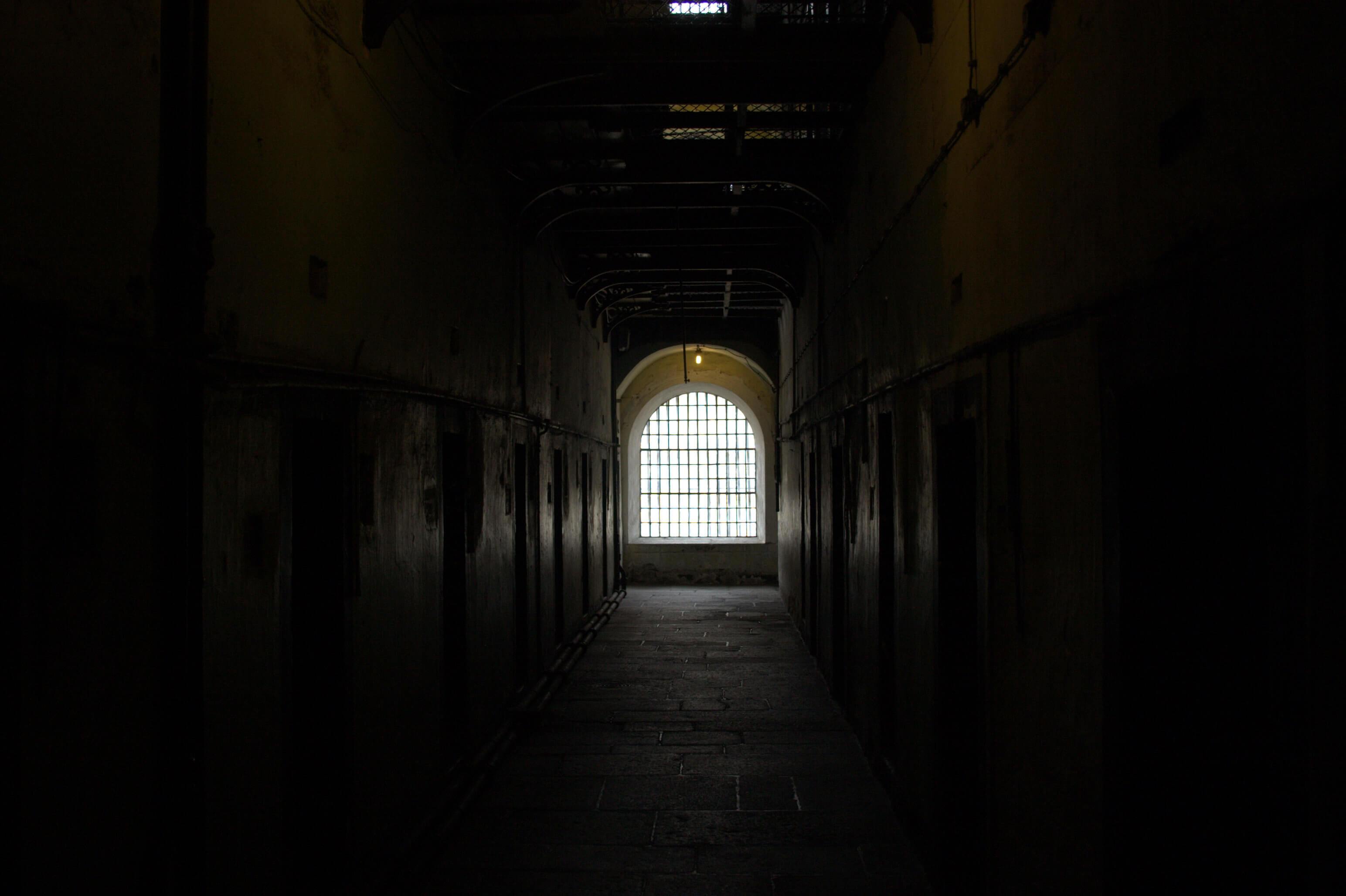

Reina Maraz – in blue – with her defense lawyer and interpreter in court November 2014. Credit – Agencia ANDAR.

Sexual Violence and ‘that night’

Maraz told in court how one night Limber Santos and Vilca went out drinking. Around 5am, Vilca came back to the kiln and into Maraz’s room, where she was sleeping with the children. He woke her and horrifyingly told her ‘your husband owes me a debt, and he gave me you.’ Then he raped her in front of her children.

The lead judge, Marcela Alejandra Vissio, described the incident as improbable in her verdict because Maraz did not make a police report. But not filing a police report for rape is not unusual for women, who face significant barriers in the legal system such as reliving trauma and being victim-blamed. Data on unreported rape is hard to find in Argentina, as in many countries, but it is likely to be far under-reported. On top of the usual barriers, Maraz has the additional barrier of not fully understanding or speaking Spanish.

The aftermath of Maraz’s rape included a vicious beating at her husband’s hands. It also sparked violent conflict between Vilca and Santos.

On the morning of her husband’s death, 14 November 2010, Maraz got up at 4am to help him prepare for a trip to visit his sister to pay her back a debt. Maraz explained in court that Vilca was also up that morning, drunk. Limber Santos and he started arguing through the window of the room, and then Santos went out. At that moment, Maraz heard the sound of a padlock locking her and the children into the room.

The person who removed the lock and came into the room shortly after was not Maraz’s husband, but Vilca. She asked him where her husband was, and Vilca said Limber Santos had left for his sister’s. Then he raped her again, again in the presence of her two children.

The Aftermath of Limber Santos’ death

Maraz had no idea that her husband was dead at that moment. When there was no sign of him, she went to stay at her father-in-law’s house with her sons. She testified that she was afraid to stay at the brick kiln because of Vilca’s presence. And she went to the police and reported her husband as missing – she was worried he had been robbed when he didn’t appear at his sister’s.

Limber Santos’ body was then found in a rubbish heap on the grounds of the brick kiln. Maraz and Tito Vilca were arrested and jailed as responsible. In jail, Maraz discovered she was pregnant. Her little girl was born in Unit 33 of Prison Los Hornos of Buenos Aires.

It took nearly a full year until Maraz was informed of the charges against her in her own language. The Argentine human rights advocacy organization La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria —‘The Provincial Commission for Memory’ — carried out one of its regular prison inspections in Prison Los Hornos and realized that Maraz was unable to communicate well in Spanish. They brought a Quechua speaker to visit her.

The Battle for an Interpreter

When Maraz faced trial in October 2014, she had Frida Rojas, a Quechua-speaking interpreter, at her side. Accessing this basic right for Maraz took over two years of advocacy and legal formalities, headed by the Commission for Memory.

The battle included a trip to the Supreme Court of Argentina, who ordered the criminal court to provide Maraz with an interpreter. Even so, the Argentine state made the Commission jump through many more hoops to get Maraz the interpreter she had a right to.

Dr. Mariana Katz is in charge of the Commission’s program for Indigenous and Migrant Peoples. Katz is a lawyer, and was an observer at Maraz’s trial. In a recent interview with Intercontinental Cry, Katz said, “In all of these delays and official proceedings, the person who suffers is Reina.”

She went on, “For the Commission, the legal basis [of Maraz’s conviction] is invalid, because from the very first moment [of her arrest] they should have provided her with an interpreter.”

Language Discrimination in Court

In another violation of rights, Maraz’s sister was forbidden by the judges from testifying in her native language, even though the Quechua interpreter was present in court that day.

“When they asked her questions it was clear she didn’t understand, because she was answering something different to the question she was asked,”Katz said. “On top of that, the judges were getting annoyed.”

To convict Maraz, the judges relied on testimony from her 5-year-old son who couldn’t speak Spanish fluidly. “When they brought the boy to declare, he had to be asked the questions several times, because he also has difficulties in Spanish,” explained Katz.

Maraz’s eldest son testified in a Gesell Dome, a one-way mirror system used by law enforcement. Three expert psychologists brought to testify by Maraz’s defense lawyer discredited the Gesell Dome testimony independently of each other. They said it was carried out as an interrogation using leading questions and not as it should be — a psychological test where the child is given time to express themselves through play. Despite all this, the judges did not take into account the three psychologists’ testimony.

The judges also ignored language subtleties that could have led to different interpretations of the boy’s testimony. It was also questionable whether to allow testimony from a 5-year-old who had been subject to traumatic experiences.

More Evidence Dismissed by Judges

Other important evidence was dismissed by the judges. Vilca was also arrested for Santos’ murder. While he was in jail, the Vice Consul of Bolivia to Argentina, Jorge Valentín Herbas Rodriguez, visited him. When Vilca began to tell him the story of what had happened the night of Limber Santos’ death, Herbas stopped him and told him to save it for court. Vilca died in jail before he got a chance to tell his story in court.

Herbas testified at Maraz’s trial. It was clear that Vilca was likely to have made a full confession had he lived. But the judges dismissed the word of the diplomat as “indirect testimony.”

On 11 November 2014, the three judges unanimously declared Maraz guilty of doubly aggravated homicide. The aggravating factors were premeditation and motive of robbery. The judges thought that Maraz and Vilca were lovers and planned to murder Limber Santos for the money he was carrying, which was barely $70US.

For this alleged crime, they condemned Maraz to a life spent in prison.

“They gave Reina the same sentence they give to perpetrators of the genocide [Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’],” Katz said.

Reina Maraz has been condemned to a life in prison. Her appeal is asking for her freedom. Credit -feelsgoodlost on flickr – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Reactions to the Sentence

The gross injustice of the Argentine judicial system did not go unnoticed. Feminist activists from several organizations protested outside the court (and have continued to protest). Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Nobel prize winner and President of the Commission for Memory, wrote an article entitled The 3 Deadly Sins: Woman, Indigenous and Poor.

Maraz’s defense lodged an appeal in Argentina’s Court of Cassation (a certain type of appeal court that examines the interpretation of the law). The Commission together with feminist and human rights organizations have submitted a briefing to the judges (an Amicus Curiae). They stressed that Maraz did not have a fair trial. The vulnerabilities of a non-Spanish speaking migrant indigenous woman were not taken into account by Maraz’s judges, they said.

The demand is for Reina Maraz’s freedom. Failing that, advocates are calling for her sentence to be transmuted to the most lenient sentence for homicide in Argentina, eight years imprisonment, of which she would have already served six. There is no date set yet for the hearing of the appeal.

The Commission believes fully that Maraz is innocent. “We (the Commission) believe in Reina’s innocence, because for nearly 6 years, when she is asked about the facts, she always tells the same story with no cracks,” Katz said. “If it were invented, she would not be able to tell the same story without some level of error. This gives us the certainty that she is innocent.”

An emblematic case of indigenous discrimination

The lead judge Vissio repeatedly stated in her verdict that Maraz, Maraz’s sister Norma Bejarano, and Maraz’s eldest son were all fluent in Spanish. The court treated their need for interpretation of the Spanish language as no more than a defense tactic. The results of this attitude were rights violations; Maraz’s sister and son were never allowed to testify in Quechua.

By Argentine law, this was illegal, but the country’s courts still don’t have interpreters on file for more languages than English, French and Portuguese — notably, all colonial languages.

It’s a symptom of a deep-seated societal norm. “We have a problem in Argentina where people think that there are very few indigenous people, despite the history of indigenous struggle in the country,” Katz said. “There is a cultural conceptualization that indigenous people don’t exist.”

The judges’ actions and verdict speak to this attitude: migrants or indigenous peoples must speak the host country’s or the colonizer’s language; if they don’t, it’s their own fault. It is deeply unfair and deliberate: they are actions that make Indigenous Peoples invisible.

Reina Maraz, Survivor

Maraz was already a survivor of terrible violence; physical and psychological violence committed by her husband and his family, and sexual violence at the hands of Tito Vilca.

Now she is surviving violence at the hands of the Argentine state. Maraz is currently under house arrest, and suffering health problems. House arrest instead of jail was a small comfort achieved by activists, principally so that she can look after her young daughter. Her other two children are in Bolivia with her parents. She hasn’t seen them in a number of years; another type of punishment.

The hope now is that the judges who hear Maraz’s appeal are subject to enough pressure to drop the charges against her.

The Argentine state not only ignored Maraz’s proven status as a Quechua-speaking migrant and so prevented her from accessing a fair trial; they used her vulnerabilities as a weapon to condemn her. These are deeply misogynist and racist actions. Reina Maraz has already been unjustly imprisoned for six years. To free her now would be the bare minimum of justice.

All references come from the author’s original interview with Dr Mariana Katz; La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria’s full coverage of Reina Maraz’s situation and trial; and the verdict of Reina Maraz’s trial.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 11, 2016 | Gender

by Meghan Murphy / Feminist Current

Planned Parenthood, as you may know, is the largest single provider of reproductive health services in the United States. The non-profit defines itself as “leading the reproductive health and rights movement,” and has supported millions and millions of women, over the past century, in accessing pregnancy tests, contraceptives, sex education, STD tests, abortions, and more. But do they know how women’s reproductive systems work?

Recent actions leave us guessing.

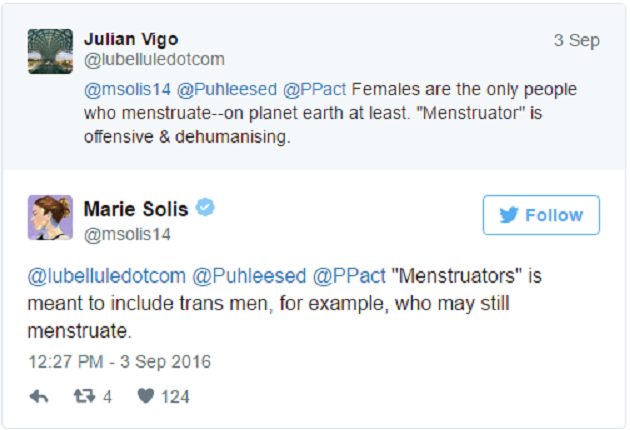

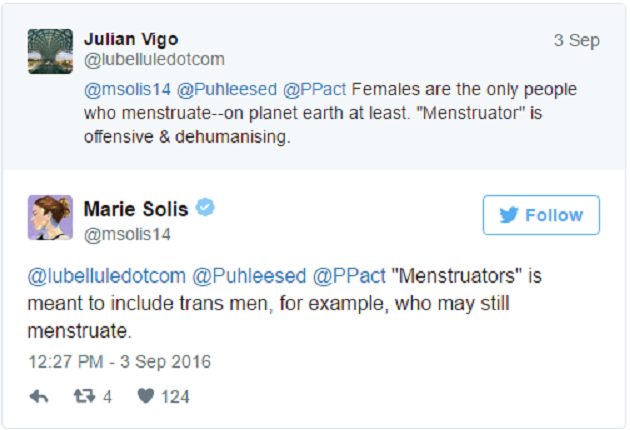

On September 2nd, Planned Parenthood tweeted, “Menstruators in New York started to #TweetTheReceipt celebrating the repealed tampon tax — but some are still charged.”

Many were left wondering what a “menstruator” was — previous to this, we’d all simply referred to each other as “women.” But it seems that Planned Parenthood’s social media intern is not the only one confused about the fact that literally only female bodies are capable of menstruating.

Marie Solis, a writer for Mic responded to the immediate push back from women, angered at having been reduced, essentially, to bleeders, by explaining, “Not everyone who menstruates is a woman! @PPact is using ‘menstruators’ to be inclusive.”

Inclusive of whom, you might ask? Solis responds, “‘Menstruators’ is meant to include trans men, for example, who may still menstruate.”

Conundrumy! How is it possible for a human being — trans or not — to menstruate if they do not, in fact, have ovaries and a uterus? Well, hold on to your hats, folks — the answer is: it’s not possible. Every single person who menstruates has a female body. Does this make you feel uncomfortable? Apparently it makes Planned Parenthood uncomfortable, which is odd, as they, of all people, should understand these basic facts about women’s bodies, as experts and educators on the very topic of women’s bodies.

Despite the fact that numerous women were kind enough to remind Planned Parenthood that it was ok to acknowledge that women’s bodies are real things that exist and are different from men’s bodies, the non-profit was back at it again the very next day, tweeting, “Purvi Patel has been released from prison, but people continue to be criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes.”

Who are these “people” who “continue to be criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes,” you might also ask. Has a man ever, in all of history, been criminalized for his pregnancy outcome? The answer, of course, is no. That has literally never happened. Purvi Patel was jailed because she has a female body, and that female body, once pregnant, miscarried. Apparently, punishing women based on the way their pregnancies end is ever-popular in the U.S., as well as in many other countries. This practice has put countless women’s lives in danger and contributes to our ongoing marginalization, but hey, no need to acknowledge this reality as a gendered one. Women’s rights are people’s rights, after all.

Oh wait, that’s not right.

You see, the reason patriarchy exists is because men decided they wanted control over women’s sexual and reproductive capacities. Not people’s sexual and reproductive capacities — women’s. Sexual subordination is a gendered phenomenon, no matter how you identify, and for an organization that exists to advocate on behalf of women — due to their female biology (you know, the thing that placed them, whether or not they chose it or like it, within an oppressed class of people) — to erase that is unconscionable.

A woman is an adult female human — it really is as simple as that. And understanding how that reality is at the root of our ongoing oppression under patriarchy is one thing that is not up for debate.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2016 | Gender

New Books Highlight the Debate between Radical Feminism and Transgender Movement

by Robert Jensen

Within feminism there has been for decades an often divisive debate about transgenderism. With increasing mainstream news media and pop culture attention focused on the issue, understanding that feminist debate is more important than ever.

Two new feminist books that analyze transgenderism (Sheila Jeffreys’ Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism and Michael Schwalbe’s Manhood Acts: Gender and the Practices of Domination, which includes a chapter on “The Limits of Trans Liberalism”) are helpful for those who are concerned about the harms that result from the imposition of traditional gender roles but do not embrace the ideological assumptions and assertions of the transgender movement.

The propositions below are not taken directly from those books, whose authors may not agree with my phrasings. I am not trying to summarize their arguments but instead hope to bring greater clarity to the debate with a concise account of my position, which is rooted in a radical feminist analysis of sex and gender. I present these ideas as a series of propositions to make it easier for readers to identify where they may agree or disagree.

Biological and Cultural

We are a sexually dimorphic species, male and female. Although there is variation, the vast majority of humans are born with distinctly male or female reproductive systems, sexual characteristics, and/or chromosomal structure. Intersex people are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the definitions of female or male; the number of people in this category depends on the degree of ambiguity used to mark the category. Intersex conditions are distinct from transgenderism.

The biological differences between males and females that are tied to reproduction are not trivial; no species can ignore reproductive realities. Not all females have children, but only females can bear and breastfeed children, which no male can do. Therefore, human communities have always, and will always, recognize two distinct sex categories, male and female. There has always been, and always will be, some sex-role differentiation in human communities.

Other observable or measurable physical differences (average height, muscle mass, etc.) between males and females may be socially relevant depending on circumstances. Sex-role differentiation based on those differences may be appropriate if it can be shown to be necessary in the interests of everyone in a society. This claim is asserted far more often that is demonstrated.

People from varying ideological positions also claim that these biological differences give rise to significant differences in moral, intellectual, or emotional characteristics between males and females. While it is plausible that differences in reproductive organs and hormones could result in these kinds of differences, there is no clear evidence for these claims. Given the complexity of the human organism and the limits of contemporary research, it’s unlikely we will gain definitive understanding of these questions in the foreseeable future. In the absence of evidence of the biological bases for moral, intellectual, or emotional differences, we should assume that all or part of any differences in observed behavior between males and females in these matters are a product of cultural training, while remaining open to alternative explanations.

In short: males and females are far more similar than different.

Patriarchy

Today’s existing sex-role differentiation is the product of a patriarchal society based on male dominance. In that system, males are socialized into patriarchal masculinity to become men, and females are socialized into patriarchal femininity to become women.

In patriarchy, sex-role differentiation supports male power and helps make the system’s domination/subordination dynamic seem natural and normal. Moral, intellectual, and emotional traits are assigned differentially to each sex, creating what we today typically call gender roles. This patriarchal system of control—which is complex, adapting to changing conditions and to resistance—is designed to justify and perpetuate male dominance.

The gender roles in patriarchy are rigid, repressive, and reactionary. These roles constrain the healthy flourishing of both males and females, but females experience by far the most significant psychological and physical injuries from the system.

In patriarchy, gender is a category that functions to establish and reinforce inequality.

Radical Feminism

In contemporary culture, “radical” is often used dismissively as a synonym for “crazy” or “extreme.” In this context, it describes an analysis that seeks to understand, address, and eventually eliminate the root causes of inequality.

Radical feminism opposes patriarchy and male dominance. Radical feminism, which challenges the naturalizing of the process by which patriarchal societies turn male/female into man/woman, rejects patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender roles.

Radical feminist politics addresses a wide range of issues, including men’s violence and sexual exploitation of women and children. Many radical feminists critique the gendered dress/grooming/presentation norms imposed on females in patriarchy, such as hyper-sexualized clothing, make-up, and ritualized behaviors of subordination, arguing for the elimination of these practices, not for males to adopt them as well.

The goal of radical feminism is a world without hierarchy, in which males and females would be free to explore the range of human experiences—especially experiences of love, whether sexual or not—in an egalitarian context.

Transgender

Transgender is defined as “A term for people whose gender identity, expression or behavior is different from those typically associated with their assigned sex at birth.” The transgender movement rejects the automatic sorting of males and females into the categories of man and woman, but does not necessarily reject gender roles. Some in the transgender movement embrace patriarchal gender roles typically attached to the cultural categories of masculinity and femininity.

While not all people who identify as transgender have sex-reassignment surgery or use hormones or other treatments to modify their bodies, the transgender movement as a whole accepts and/or embraces these practices.

Most radical feminists, who seek to eliminate patriarchy and patriarchal gender ideology, disagree with this transgender approach. Most radical feminists believe liberation is achieved through a political project that transcends patriarchal gender, rather than accepting those gender roles and merely seeking to allow people to move between the categories. Radical feminist politics focuses on challenging the patriarchal gender ideology that restricts the freedom of most individuals, especially women and others who lack power, to explore the fullest range of human experiences.

Nothing in a radical feminist analysis minimizes the social and/or psychological struggles of—nor provides support for violence against—people who identify as transgender or people who do not conform to patriarchal gender norms but do not identify as transgender. Radical feminism is not the cause of those struggles or the source of that violence but rather advocates for an egalitarian society with maximal freedom without violence.

Ecology

Many people, whether radical feminist or not, are critical of high-tech medicine’s manipulation of the body through the reckless use of hormones and chemicals (which rarely have been proved to be safe) or the destruction of healthy tissue to conform to arbitrary beauty standards (cosmetic surgery such as breast augmentation, nose jobs, etc.).

From this ecological approach, such medical practices are part of a deeper problem in the industrial era of our failing to understand ourselves as organisms, shaped by an evolutionary history, and part of ecosystems that impose limits on all organisms.

People are not machines, and treating the human body like a machine is inconsistent with an ecological understanding of ourselves as living beings who are part of a larger living world.

Public Policy

The state should not limit people’s freedom to choose, when those choices do not harm others. Disagreements can, and do, arise over identifying and assessing harms.

Transgender claims have led to a variety of policy debates, especially concerning the integrity of female-only spaces that are designed to foster a sense of safety and expressive freedom for females generally (such as cultural institutions) and particularly to create safety for females who have been victims of male violence (such as rape crisis and domestic violence centers). Forcing female-only spaces to accommodate people who identify as transgender reinforces patriarchy as a system and harms individual females.

Public funding for sex-reassignment surgery (such as through Medicare) raises serious public health questions that cannot be resolved by simplistic freedom-to-choose arguments.

Transgender practices involving children that are questionable on public health grounds (such as the use of puberty blockers) raise serious moral questions about our collective obligation for children’s welfare.

Intellectual Practice and Rhetoric

As in any contentious political debate, angry and uncivil words have been exchanged. People on all sides should be respectful and careful in choices of language.

Labeling a radical feminist position on these public policy issues as inherently “transphobic” or describing radical feminist arguments on the issues as “hate speech” are diversionary tactics that undermine productive intellectual and political discussion. A critique of an idea is not a personal attack on any individual who holds the idea.

This critical analysis does not demand that people accept these principles in constructing an individual sense of self. These propositions are relevant to such individual decisions, but are presented in the context of collective decision-making about public policy.

Conclusion

Transgenderism is a liberal, individualist, medicalized response to the problem of patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms. Radical feminism is a radical, structural, politicized response. On the surface, transgenderism may seem to be a more revolutionary approach, but radical feminism offers a deeper critique of the domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of patriarchy and a more promising path to liberation.

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include Arguing for Our Lives: A User’s Guide to Constructive Dialogue (City Lights, 2013) and Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity (South End Press, 2007).

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 15, 2016 | Gender, Lobbying

By Women’s Liberation Front

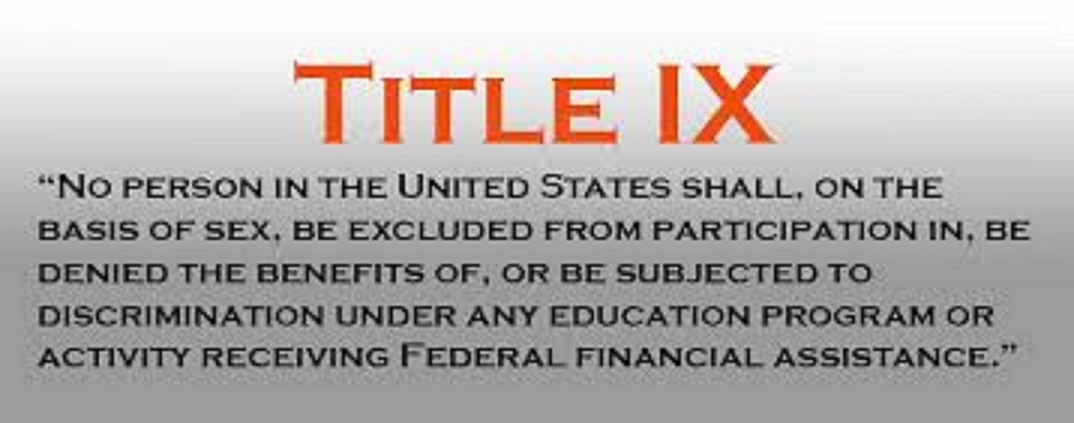

On August 11th, 2016, Women’s Liberation Front filed a lawsuit against the US Department of Justice and the US Department of Education, challenging their recent actions which have caused the dissolution of Title IX, violating the rights of women and girls, including the fifth and fourteenth amendments of the Constitution.

_______________

The swift and enthusiastic push for transgender rights in America is having dire consequences that severely threaten the privacy, dignity, safety, and equality of women and girls.

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) and Department of Education (DOE) have abruptly enacted a new policy, defining the category of “sex” in Title IX to include “gender identity.” This effectively renders Title IX meaningless, as females can no longer be recognized as distinct from males. Indeed, Title IX, the legislation used to champion the very creation of female sports, is now being used to dismantle them, as male athletes demand access to female teams, dominating the competition.

The reinterpretation of “sex” to include “gender identity” also means that girls’ bathrooms and locker rooms must be opened up to any male who “identifies” as female. Girls’ rights to personal privacy and freedom from male sexual harassment, forced exposure to male nudity, and voyeurism have been eliminated with the stroke of a pen. Schools that do not comply with the demands of any male student to access to protected female spaces will now lose federal funding.

Women’s Liberation Front (WoLF) has decided this cannot stand. The President of the United States, the most powerful man in the world, has told teenage girls that they are now required to get over their “discomfort” at boys in their locker room. We need your help to fund our legal battle against the U.S. government. We have filed a lawsuit, and we need $75,000 to see this battle into court.

If you are interested in helping with legal fees, please click here