by DGR News Service | Feb 24, 2014 | Rape Culture, Repression at Home

By William Falk / Deep Green Resistance

The San Diego Police Department scares me. All police, for that matter, scare me.

I’m writing this because I cannot drown out the sharp pops of a burst of police gunfire hanging on the still desert air.

I heard the eerily common sound of gunshots as I watched a video of police shooting an unarmed 20 year-old black man named D’Andre Berghardt near Red Rock Canyon in Nevada the other day with my partner.

A few days before viewing the video, we were on our way to Red Rock Canyon for a rock-climbing trip with friends. Highway 159 provides access to the canyon, but was closed due to a “police incident.” We made a mental note to check on the incident when we got home.

Back at home, safe on our couch in the living room, we started the video. The video was taken by two men sitting in their car as the entire encounter unfolded. You can see three or four cars stopped with drivers gawking on. There is even a bicyclist sitting on her bike seat calmly absorbing the scene.

The video opened with two officers, guns drawn, on either side of Berghardt. The officers spoke with Berghardt for a minute or so. Our disbelief grew as one officer pepper sprayed Berghardt. I paused the video to explain I’ve read that pepper spray often makes people vomit. A moment later, we watched Berghardt double over. We listened to the men taking the video asking, “Why don’t they just cuff him?” Then we watched as the officers taser Berghardt. I stopped the video again to say that tasering often causes the recipient to defecate in his or her pants. A few of the cars started turning around and driving past the scene.

Finally, my partner who is much braver than me and much more vocal, yelled out, “Why doesn’t some one do something!?”

All I could manage to say was, “I would be scared. The cops have their guns out. I’m not talking to a cop with his gun drawn.”

Then we finished the video as Berghardt eventually ran from officers who had pepper sprayed him and tasered him into an open police vehicle before being shot multiple times from a few feet away. Then, he died.

After watching the video, we learned that Berghardt had been walking down Highway 159 asking cyclists for water and telling them to “have a good ride.”

And now: I cannot drown out the sharp pops of a burst of police gunfire hanging on the still desert air.

It is time that we do something.

***

I’m writing this because I cannot drown out the voices of the women who have so bravely – despite tears, shaking voices, traumatic recollections, and even government-paid stalkers – told their stories of sexual assault at the hands of the SDPD.

With the recent news that the City Attorney’s office paid a private investigator to follow for 23 days and videotape one of former SDPD Officer Anthony Arrevalos’ sexual assault victims and now the news that another SDPD officer, Chris Hays, has been arrested on suspicion of committing false imprisonment and misdemeanor sexual battery while on duty, my fear of the police is growing stronger and stronger.

These disturbing sexual abuse allegations (and convictions) are not just here in San Diego, either. A quick Google search shows that almost identical cases of abuse are happening all over the country. Do any of these stories sound familiar? A few weeks ago in Dallas an officer allegedly told a woman he wouldn’t take her to jail if she would have sex with him. Last summer a school police officer in Eugene, OR was convicted of sexually abusing six women while on-duty and off-duty and several more women came forward after conviction. And, in Chicago, two officers are accused of raping a woman they offered a ride home while on-duty.

I have to be honest. I’ve never liked the police. It started when I was younger. I’ve always worn my hair long and have been pulled over too many times to have a cop let me go after explaining, “You have to admit, you do look like you probably have drugs on you.”

Then, I became a public defender, and learned first hand just how bad the police can be. There were too many times when I requested video evidence from squad car cameras only to find the officer ‘forgot’ to turn the camera on. Too many times I overheard senior officers telling junior officers how to testify in the hallway before hearings. Too many times I watched as police officers were cleared of claims of excessive force. Too many times I’ve seen women coming forward to report sexual abuse at the hands of police officers.

***

I’m afraid of the police. I’m particularly afraid of the SDPD because I live here, and because we keep getting report after report of their violence.

I’m also very angry. There are people who are responding to criticisms of the police with the tired rebuttal “If you don’t do anything wrong, you don’t have anything to be afraid of.”

D’Andre Berghardt wasn’t doing anything wrong. The women in Eugene, OR assaulted by a school cop weren’t doing anything wrong. The woman who took a ride home from police officers before being raped by both of them wasn’t doing anything wrong.

And what about the definition of “wrong?” It’s not wrong to smoke recreational marijuana in Washington, but it is in most of the rest of the country. Many states still have anti-sodomy laws on the books. It was wrong at one time in this country to harbor run away slaves.

And what about when the right thing to do is “wrong”? For example, who do you think is going to show up first with guns drawn if outraged citizens decided to dismantle California’s fracking sites? Who showed up at Wounded Knee in 1973 when indigenous peoples demanded the federal government honor their treaties? Who murdered Fred Hampton? Who smuggled cocaine from Nicaragua into the US? Who is teaching children to shoot likenesses of immigrants at the border? Who is shooting the immigrants?

I am afraid of the police. You should be, too, even if you’re doing nothing wrong. They will throw their phony reports at us. They will harass us if we speak too loudly. Their City Attorney will send stalkers to report on our sexual habits. And, yes, they might even point their guns at some of us.

But, we must be brave.

It is time that we do something.

From San Diego Free Press: http://sandiegofreepress.org/2014/02/im-afraid-of-the-sdpd/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 23, 2014 | ANALYSIS, Male Supremacy

By Rachel / Deep Green Resistance Eugene

Yesterday was the 41st anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that made it illegal for federal and state governments to make blanket, outright bans on abortion. For those who fight for women’s ability to exercise full autonomy and human rights, January 22nd is treated as a day of celebration and remembrance of those who fought before us. Nonprofits, advocacy organizations, and student groups from coast to coast held benefits and awareness events. Celebratory twitter hashtags and blurbs from liberal blogs are still piling up. Good news is scarce in the world of reproductive justice activism, and we’ll take it where we can get it. I won’t begrudge our beleaguered cause one day of hope – at least, not until the morning after.

The reality of our situation gives the lie to much of the hopeful rhetoric that comes rolling out every year on Roe’s anniversary. Our backward slide doesn’t look to be slowing anytime soon. If we face the the reality of what Roe has done, self-congratulatory reflections on how far we’ve come become not only ridiculous and out of touch, but insulting and dangerous as well. A prime example of the rose-colored view of Roe espoused by many in the mainstream is this sentence, written by President and CEO of Planned Parenthood Federation of America on the 38th anniversary of Roe, three years ago:

Thirty-eight years after Roe gave America’s women the right and the opportunity to plan for their families and control their reproductive health, this tenet of modern American rights is under assault. [1]

It’s deeply disturbing to see someone in Richards’ position giving credence to the fantasy articulated here, even while she acknowledges that our meager gains are under threat. After all the dust had settled, Roe and the relevant subsequent court decisions made it illegal for federal and state governments to ban abortion outright before the point of a fetus’s viability outside the womb– that’s it. There is no language whatsoever in the entire decision that guarantees women the right to an abortion. If there was such language, women would be able to use the precedent of Roe to sue their government if they, for instance, were prevented by lack of resources from obtaining an abortion. This is not the case.

The decision in Roe was based on the right to privacy in the 14th Amendment, a right most often invoked within the law to protect consumer decisions. Within a for-profit healthcare system, medical decisions are consumer decisions, and only middle to upper class (predominantly white) women have the resources to exercise meaningful choices regarding abortion. Roe doesn’t challenge that fact – it affirms and reinforces it.

Even more laughable is the idea that Roe gave “America’s women” the opportunity to access abortion. From the beginning, the only American women who were granted the opportunity to control their reproduction were those who could pay. The Hyde Amendment banned Medicare from covering abortion access just a few short years after Roe, effectively obliterating abortion access for millions of poor women. The oft-repeated mantra of “never go back” loses all meaning when in reality, only a select group of women were ever permitted to escape. The slow strangle of targeted regulation and domestic terrorism campaigns make abortion progressively more expensive to obtain, as women have to travel further to reach clinics. Roe does not confer rights or opportunity, it bestows privilege upon women of means.

In the three years since Cecile Richards wrote that sentence, more restrictions on reproductive freedom have been enacted than in the ten years prior. Eighty seven percent of counties have no abortion provider. Insurance bans and medicare prohibition like the Hyde Amendment, combined with geographical obstacles, TRAP laws, and the constant threat of violence against women and clinic workers, make abortion inaccessible or a significant hardship for the majority of women in the United States. Legislation granting personhood to pregnancies (and thereby taking personhood away from women) continues to advance, and record numbers of women are being jailed for failing to successfully carry their pregnancies to term. One hopes that in recent years, Richards and her organization have been disabused of such fantastical notions of Roe’s capabilities. Indeed, this year’s obligatory missive from PPFA takes a somewhat more urgent tone.

Roe is not enough, and we know it. But stopping at acknowledging Roe’s shortcomings still glosses over the reality of what Roe has done – and it’s not all good.

Most contemporary discussion of the “Pre-Roe Era” goes something like this: “Before this landmark decision, abortions were completely illegal, and desperate women had to resort to unsafe, backalley procedures, many of which resulted in their deaths.” [2]

The above narrative is a popular just-so story, but it completely obscures the reality of how women were forced into the horrific situations it describes. This narrative is not only incomplete, it’s also Euro-centric. Many indigenous cultures practiced a variety of methods for terminating pregnancy and controlling reproduction. European invasion, colonization, and the ongoing genocide of indigenous peoples has meant the almost total erasure of traditional knowledge including that of how abortions were performed. The systematic rape of indigenous women as a weapon of war continues today, further denying them any reproductive control. Starting in the early sixteen hundreds, captured Africans sold as slaves were denied any and all reproductive control. Female slaves and freed African women experience both forced childbirth and forced sterilization, both of which continue. Last year it came out that at least 148 women were forcible sterilized between 2006 and 2010 in the California prison system. [3]

Supporters held a candlelight vigil in front of the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 22, 2005, to commemorate the 32nd anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision. (Pablo Martinez Monsivais, Associated Press)

The history of reproductive restriction on this continent dates back to well before the official inception of the United States, however the kind of criminalization that Roe attempted to address is a phenomenon unique to the last couple centuries. Abortion was surprisingly accepted among early European settlers up until the point of “quickening,” which referred to the first time a woman felt her fetus move within her womb. Individual women of course were often controlled in all aspects of life, including reproduction, by their husbands and fathers – something that continues today. But abortion was legal for white women up until that certain point in pregnancy. Practitioners were often midwives, or women without formal medical training. Many popular abortion techniques were medicinal and therefore there was no abortionist, only the woman. Colonial home medical guides gave recipes for “bringing on the menses” with herbs that could be grown in one’s garden or easily found in the woods. These were not always safe, but they were not illegal, and they were largely under female control.

In the 1820’s, states began outlawing abortion, and though these laws were couched in religious language just as they are today, the rise of abortion restriction mirrored rising fears that the higher birthrate of racial and religious minority populations would lead to a protestant minority and a white minority, an idea that still sends shivers down the spines of our white male leaders.

In 1868 Horatio R. Storer, one of the leading anti-abortion crusaders, is quoted:

Will the West be filled by our own children or by those of aliens? This is a question our women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation. [4]

Unfortunately, Storer and other physicians were not satisfied to leave the answer to that question up to women or our loins. They decided to take matters into their own hands. In the late eighteen hundreds, the American Medical Association (which was then an entirely male controlled institution) lobbied aggressively for the criminalization of abortion.

The frightful extent of [abortion in the US] is found in the grave defects of our laws, both common and statute, as regards the independent and actual existence of the child before birth, as a living being. These errors, which are sufficient in most instances to prevent conviction, are based, and only based, upon mistaken and exploded medical dogmas. -1859 AMA Committee [5]

So according to these men, the prevalence abortion was not based on the needs or decisions of women, but on incorrect medical understanding. If this was true, then as the newly knighted elite of the medical industry, they were conveniently declaring themselves as the only authorities qualified to correct the medical misunderstanding that lead to abortion. This was a bid for control, because it ensured that the only people who had the authority to perform abortions were male, formally trained physicians. By 1900, every state had abortion restrictions on the books, and it’s been all downhill from there. There’s a lot of information and analysis out there about the medicalization of birth, and how the absorption of reproduction into the medical industry, and the reclassifying of birth from a natural process to a medical phenomenon, has been bad for women overall. This is also true of the medicalization of abortion. The practice of medicine during this period went from a more community based structure with widwives and female healers having a place particularly in reproductive aspects of health, to the absorption of this community structure into the commercial medical industry. The medicalization and the criminalization of abortion went hand in hand. Both increased male control and decreased female reproductive autonomy.

Roe does nothing to challenge this hostile takeover of female reproductive decisions by male dominated institutions. Roe codifies governmental regulation of abortion in law, and it institutionalized the total dependence of women on the medical industry with regard to reproduction. Never once in the text of Roe v. Wade is a woman referred to as having made a decision on her own; every single time a woman’s decision is mentioned, it’s as “a woman and her physician.” When we put this language into context with the usurption of reproductive control by the commercial medical industry, the effect of Roe becomes a lot more sinister.

In all of our romanticization of Roe’s effects, why do we never speak of the fact that in the pre-Roe era, women weren’t fighting the government over how abortion should be regulated – they were fighting over whether the government had the right to exercise any control over female reproduction. By accepting governmental regulation as a baseline, we’re giving up ground that pre-Roe activists fought for tooth and nail. NARAL – which now stands for National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League – was original named National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws. During some demonstrations, activists would hand out sheets of paper with their ideal version of abortion restriction – and it was a blank sheet of paper. Our foremothers knew that if we accept any control over reproduction by the government and medical industry, we fail utterly to protect women’s reproductive autonomy.

The text of the Roe decision also left one obvious and frightening door to the total criminalization of abortion wide open, and it didn’t take the law very long at all to force through that door. The text of the decision says:

The available precedent persuades us that the word “person,” as used in the Fourteenth Amendment, does not include the unborn. […] If this suggestion of personhood is established, the appellant’s case, of course, collapses, for the fetus’ right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the Amendment.

And unsurprisingly, in 1989 with Webster v. Reproductive Health Services the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of language in a Missouri statute that asserts that “the life of each humanbeing begins at conception” and “unborn children have protectable interests in life, health, and wellbeing.” The law being upheld required that all Missouri state laws be interpreted to provide unborn children with rights equal to those enjoyed by other persons – which effectively revokes legal personhood from pregnant women. This ruling set the stage for the several personhood law attempts we’ve seen recently. The first of these was passed into law in North Dakota and is now viable precedent. The door to criminalization left open by Roe has been effectively blown off its hinges.

The logical conclusion of codifying fetal personhood into law is that women are being criminally prosecuted when their pregnancies do not end in live birth. Over the last few years we’ve seen women in the US brought up on charges that they somehow caused their miscarriages. Bills criminalizing miscarriage have been proposed in several states, and in some, the courts have acted on them. In 2009 Nina Buckhalter was indicted by a grand jury in Lamar County, Mississippi, for manslaughter, claiming that the then 29 year old woman “did willfully, unlawfully, feloniously, kill Hayley Jade Buckhalter, a human being, by culpable negligence.” This was after Nina had a stillbirth at 31 weeks. The National Association for Pregnant Women has documented more than 400 cases across the country in which these laws have been used to detain or jail pregnant women for supposedly endangering their pregnancies. 71 percent of these are, unsurprisingly, likely to be low income women.

Instead of granting women the right to obtain an abortion, Roe v. Wade affirmed the right of the medical industry and government to make decisions for women. Instead of providing women with the opportunity to access abortion, Roe v. Wade affirmed that abortion is a privilege only afforded to a lucky, monied few. Instead of moving the fight for Reproductive Justice forward, Roe v. Wade conceded most of the ground that pre-Roe activists were fighting for. To top it all off, Roe includes a specific directive on personhood that has paved the way for those who would love to see abortion eradicated. Why are we surprised that things have become steadily worse since Roe was decided? Why have we let ourselves forget what actual reproductive autonomy even looks like? Next year on Roe’s anniversary, and the whole year in between, let’s stop being satisfied with weak reforms that simply reinforce the status quo. Let’s take a hard, honest look at what is at stake when we laud Roe for what it can’t do and completely forget what it has done – the good and the bad.

Notes

[1] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/cecile-richards/roe-v-wade-38-and-under-a_b_812531.html

[2] http://thequakercampus.com/2013/02/07/students-and-faculty-reflect-over-roe-v-wade-40th-anniversary/

[3] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/alex-stern/sterilization-california-prisons_b_3631287.html

[4] http://horatiostorer.net/AMA_vs_Abortion.html

[5] http://books.google.com/books?id=iQN0NsOUBGsC&pg=PA100&lpg=PA100&dq=ama+frightful+extent+of+abortion&source=bl&ots=ubgMYfYhDW&sig=1rkvS7-OezSXB7BLEQckdAzg_rA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=0IXhUpvmB9GCogTxuoLgCg&ved=0CEgQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=ama%20frightful%20extent%20of%20abortion&f=false

Photo by Aiden Frazier on Unsplash

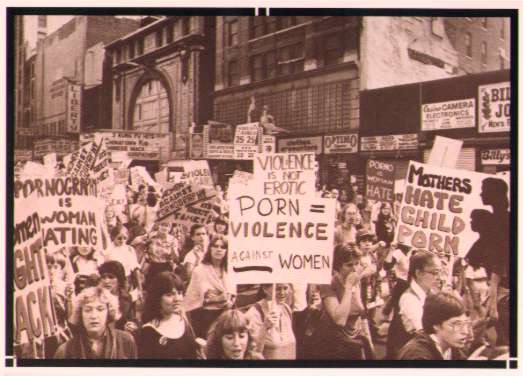

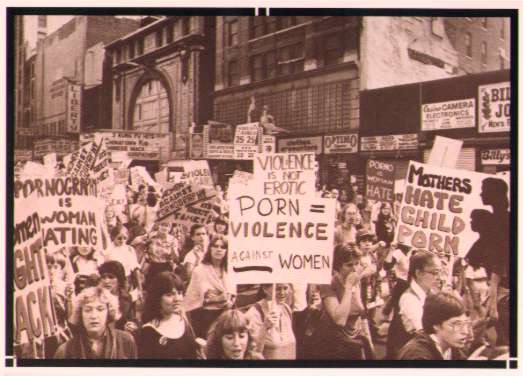

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 1, 2014 | Pornography

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

This essay was originally published in the Fall 2013 edition of Voice Male.

If the fight against pornography is a radical one, where are the radicals fighting against pornography?

Earlier this year, the 18th annual Bay Area Anarchist Bookfair, an event that brings together radical activists from around the world, was held at the headquarters and production facility of so-called “alternative” porn company, Kink.com.

Kink.com is known for its unique brand of torture porn. As Gail Dines reports, women are “stretched out on racks, hogtied, urine squirting in their mouths, and suspended from the ceiling while attached to electrodes, including ones inserted in their vaginas.” But to grasp the agenda of Kink.com, we can just go to the source: founder Peter Acworth started the company after devoting his life to “subjecting beautiful, willing women to strict bondage.”

When the Anarchist Bookfair announced its choice of venue, feminists were outraged. The few who were billed to speak during the event dropped out. But ultimately, the decision was defended, the outcry lashed back against, and the show went on.

Anarchists are my kind of people—or so I thought. When I first discovered the radical Left some eight years ago, I thought I’d stumbled on the revolution. The rhetoric seemed as much: brave, refreshing demands for human rights, equality, and liberation; a steadfast commitment to struggle against unjust power, however daunting the fight.

It wasn’t long, though, before my balloon of hope burst. To the detriment of my idealism and trust, the true colors of my radical heroes began to show.

Pornography was then and is now one such let down. Over the years, I’ve bounced between a diversity of groups on the radical Left: punks, Queers, anarchists, and many in between. But wherever I went, porn was the norm.

Here’s the latest in radical theory: “We’re seventeen and fucking in the public museum. I’m on my knees with your cock in my mouth, surrounded by Mayan art and tiger statues. Our hushed whispers and frenzied breathing becomes a secret language of power. And us, becoming monstrous, eating-whole restraint and apology. The world ruptures as we come, but it isn’t enough. We want it all, of course—to expropriate the public as a wild zone of becoming-orgy, and to destroy what stands in our way.” I’m sad to report that this quote, and the book it comes from, reflects one of the most increasingly popular of the radical subcultures.

Conflating perversion and revolution is nothing new. We can trace the trend all the way back to the 1700s in the time of the Marquis de Sade, one of the earliest creators and ideologues of pornography (not to mention pedophilia and sadomasochism).

Sade was famous for his graphic writings featuring rape, bestiality, and necrophilia. Andrea Dworkin has called his work “nearly indescribable.” She writes, “In sheer quantity of horror, it is unparalleled in the history of writing. In its fanatical and fully realized commitment to depicting and reveling in torture and murder to gratify lust, it raises the question so central to pornography as a genre: why? why did someone do . . . this? In Sade’s case, the motive most often named is revenge against a society that persecuted him. This explanation does not take into account the fact that Sade was a sexual predator and that the pornography he created was part of that predation.” Dworkin also notes that “Sade’s violation of sexual and social boundaries, in his writings and in his life, is seen as inherently revolutionary.”

Despite all they seem to share in common, most of today’s radicals actually don’t revere the Marquis de Sade. Rather, they look to his followers; namely, one postmodern philosopher by the name of Michel Foucault, no small fan of Sade, whom he famously dubbed a “dead God.”

Foucault’s ideas remain some of the most influential within the radical Left. He has catalyzed more than one generation with his critiques of capitalism, his rallying cries for what he calls “social war,” and his apparently subversive sexuality. Foucault, who in fact lamented that the Marquis de Sade had “not gone far enough,” was determined to push the limits of sexual transgression, using both philosophy and his own body. His legacy of eroticizing pain and domination has unfortunately endured.

So where are the radicals in this fight against pornography? The answer depends on who we call radical. The word radical means “to the root.” Radicals dig to the roots of oppression and start taking action there—except, apparently, when it comes to the oppression of women. How radical is it to stop digging half way for the sake of getting off?

What is called the radical Left today isn’t really that. It’s radical in name only and looks more like an obscure collection of failing subcultures than any kind of oppositional movement. But this is the radical Left we have, and this one, far from fighting it, revels in porn.

Just as we need to wrest our culture from the hands of the pornographers, we need to wrest our political movements from the hands of the sexists. Until we do that, so-called “radical” men will continue to prop up sexual exploitation under the excusing banner of freedom and subversion.

This male-dominated radical Left is expressly anti-feminist. In a popular and obscene anarchist essay, “Feminism as Fascism,” the author—who is male, need I mention—ridicules feminists for drawing any connection whatsoever between porn and violence against women. He concludes that feminism—rather than, say, the multi-billion dollar porn industry—is a “ludicrous, hate-filled, authoritarian, sexist, dogmatic construct which revolutionaries accord an unmerited legitimacy by taking it seriously at all.”

I’ve ceased to be surprised at the virulent use and defense of porn by supposedly radical—and even “anti-sexist”—men. The two have always seemed to me to go hand-in-hand.

My first encounter with radicals was at a punk rock music show in the basement of a stinky party house. I stood awkwardly upstairs, excited but shy. Amidst the raucous crowd, a word caught my ear: “porn.” Then, another word: “scat.” Next, the guys were huddling around a computer. And I was confused . . . until I saw.

More sophisticated than the punks, the anarchist friends I made a few years later used big words to justify their own porn lust. Railing against what they deem censorship, anarchists channel Foucault in imagining themselves a vanguard for free sexual expression, by which they really mean, men’s unbridled entitlement to the use and abuse of women’s bodies. And any who take issue with this must be, as one anarchist put it, “uncomfortable with sex” or—and I’m not making this up—“enemies of freedom.”

The Queer subculture puts the politics of sexual libertarianism into practice. Anything “at odds with the ‘normal’ or legitimate” becomes fair game. One Queer theorist explained in specifics: “Sleaze, perversion, deviance, eccentricity, weirdness, kinkiness, BDSM and smut . . . are central to sex-positive queer anarchist lives,” she wrote. As the lives of the radicals I once counted as comrades began to confirm and give testament to this centrality, I abandoned ship.

Pornography is a significant part of radical subcultures, whether quietly consumed or brazenly paraded. That it made me uncomfortable from the beginning did not, unfortunately, deter me from trying it myself. It seems significant though, that, despite growing up as a boy in a porn culture, my first and last time using porn was while immersed in this particular social scene. Who was there to stop me? With all semblances of feminist principles tossed to the wind, who was there to steer me from the hazards of pornography and towards a path of justice?

The answer is no one. Why? Because the pornographers control the men who control the radical Left. Women may be kept around in the boy’s club—or boy’s cult—but only to be used in one way or another; never as full human beings. How is it a male radical can look honestly in the face of a female comrade and believe her liberation will come through being filmed or photographed nude?

I have a dear neighbor who says, “There’s nothing progressive about treating women like dirt; that’s just what happens already.” My neighbor has little experience in the radical Left, but apparently bounds more common sense than most individuals therein. She, along with many ordinary people I’ve chatted with, have a hard time believing—let alone understanding—that people who think of themselves as radical could actually embrace and defend something as despicable as pornography. If the basic moral conscience of average people allows them to grasp the violence and degradation inherent in porn, we have to ask: what’s wrong with the radical Left?

In a way, this let down is predictable. From ideologues like Sade and Foucault, to the macho rebellion of punk bands like the Sex Pistols, to the anarchist-endorsed Kink.com, justice—for women and for all—has been a periphery goal at best for countercultural revolutionaries. Of vastly greater priority is this notion of transgression, an attempt at “sexual dissidence and subversion which challenges the symbolic order,” the devout belief that anything not considered “normal” is radical by default.

I can’t speak for you, but there are plenty of things that I think deserve not to be seen as normal. Take Kink.com, for example. Despite the cheerleading of shock value crusaders, I don’t really care how many cultural boundaries the company believes itself to be transgressing; tying up and peeing on another human being is simply wrong. If this sentiment gets me kicked out of some sort of radical consensus, so be it.

What is transgressive for some is business-as-usual oppression for others. As Sheila Jeffreys explains, “Transgression is a pleasure of the powerful, who can imagine themselves deliciously naughty. It depends on the maintenance of conventional morality. There would be nothing to outrage, and the delicious naughtiness would vanish, if serious social change took place. The transgressors and the moralists depend mutually upon each other, locked in a binary relationship which defeats rather than enables change.” Transgression, she contests, “is not a strategy available to the housewife, the prostituted woman, or the abused child. They are the objects of transgression, rather than its subjects.”

Being radical is a process, not an outcome. To be radical means keeping our eyes on justice at every instance, in every circumstance. It means maintaining the agenda of justice when picking our issues and the strategy and tactics we use to take them on. Within a patriarchy, men cannot be radical without fighting sexism. This is to say that radical activism and pornography are fundamentally at odds. Where are the radicals fighting porn? The ones worth the name are already in the heat of battle, and on the side of justice, whether or not it gets us off.

As for the rest, we’re going to have to make them. As the current radical Left self-destructs under the crushing grip of misogyny—as it already is and inevitably will—it is up to us to gather from the rubble whatever fragmented pieces of good there are left. And it is up to us to forge those pieces into a genuinely radical alternative.

Women have been doing this work for a long time. But it is by and for men that women’s lives are stolen and degraded through pornography. And it is by and for men that the radical Left colludes with this injustice. So it must now be men—the ones with any sense of empathy or moral obligation left—who take final responsibility for stopping it. Women have already mapped out the road from here to justice. Men simply need to get on board.

It’s no easy task taking on the cult of masculinity from the inside, but it’s a privileged position in comparison to being on the outside and, thus, its target. And this cult needs to be dismantled. Men need to take it down inside and out, from the most personal sense to the most global.

Men can start small by boycotting porn in our own lives, both for the sake of our individual sexualities and for the sake of the many women undoubtedly suffering for its production. Through images of dehumanized women, pornography dehumanizes also the men who consume them.

Individual rejection of pornography is necessary, but social change has always been a group project. Men must put pressure on other men to stop supporting, and at the very least stop participating in, sexual exploitation. We can demand our movements and organizations outspokenly oppose it. We can disavow them if they refuse.

As it stands, it’s hard to tell apart the radical Left and porn culture at large. Both are based on the same rotten lie: women are objects to be publicly used.

As it falls, the male-dominated radical Left can be replaced by something new and so desperately needed: a feminist, anti-pornography radical Left. Its goal: not the transgression of basic human rights, but the uncompromising defense of them.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 1, 2013 | Gender, Male Violence, Women & Radical Feminism

By Kourtney Mitchell / Deep Green Resistance

The following speech was originally given at the Stop Porn Culture Conference at Wheelock College, Boston, in July 2013.

Hello everyone, my name is Kourtney Mitchell and I am a political activist and a member of the group Deep Green Resistance. We are a radical organization dedicated to social, political and environmental justice. As an organization we ally ourselves with indigenous communities, women, people of color and the poor. Our aim is to stop the destruction of the planet and the oppression of people and animals.

We are a relatively new organization just a couple of years old but we are growing and have numerous chapters with hundreds of activists around the world who are all dedicated to stopping the genocide of the planet.

So, I’ll offer just a brief background on my experience as a man with pro-feminist activism and educating men. I attended university and it was there that I first received academic and activist training in feminism and anti-violence through the peer education program on campus.

The peer education program consists of graduate students, faculty, and staff who train undergraduate volunteers. The training includes education about the widespread violence that women face and volunteers learn to give presentations to peers on rape, sexual assault, relationship violence, and feminism.

In turn, peers would then join our organizing efforts and events. This was the most profoundly significant and life changing time for me. To travel around the country raising awareness of violence against women, facilitating workshops, speak-outs, and protests was fulfilling, not to mention meaningful. The training threw me into another world, one in which violence and misogyny could no longer be ignored. Our advisors did a really comprehensive job of giving us an adequate scope of the problem, and creating a sense of urgency about these issues.

They helped facilitate the creation of a student culture based on the belief that it is possible to end violence against women, and knowing that possibility helped galvanize us to take action. Many of us went on to make this our life’s work.

My primary role in the campus activist community was recruiting and teaching men about pro-feminism and anti-violence. I helped lead the male ally program, which included a weekly discussion group, activism in the community, pro-feminist art and performance, and collaborations with other similar programs around the country.

I remember vividly the anxiety of pouring over every detail of presentations I would be giving to men, worrying if the way I presented concepts was too complicated or if men would shut down for the rest of the talk if I said something too complicated. I left some events feeling like no one was reachable, but I also walked away feeling really good about the successes which were accomplished.

Many men joined our organizations and became quite active – some because they just felt it was the right thing to do, but many more because of personal experiences and the experiences of their loved ones. Several men randomly wandered into our office and left planning to attend the next ally meeting, and sure enough did continue coming. This was just one of the many things that kept me optimistic about bringing more men to pro-feminist ideas and activism.

Unfortunately, the campus activist community was largely liberal and very much influenced by queer theory. Pornography was widely accepted, and a real revolution against the patriarchal order was more joked about than seriously considered. It wasn’t until I was introduced to the radical feminist perspective that I began to see the flaws of the liberal approach to pro-feminist education.

The liberal approach leaves out an important aspect of the violence men commit against women: that men hate women. It’s important to say that out loud and allow it to inform our actions. The dominant culture is insane. Its norms and values are pathological, and it socializes people into roles that encourage, even necessitate abuse and exploitation in order to fulfill accepted social roles.

The systems of rewards in this culture makes it appear as if the masculine identity and domination imperative are in our best interest, and dissent is seen as blasphemy — a violation of a sacred order.

And that sacred order is gender.

Masculinity fraternizes men into a veritable cult, one that requires violence and callousness in order to ensure the privileges of membership. The liberal approach has been able to raise the awareness of some men concerning the male violence, but it doesn’t challenge men on the mechanism of their oppression of women.

Just when I thought we could really get somewhere with bringing men into pro-feminist activism, the radical analysis gave me a hard dose of reality. I had always thought that if we could just get men to stop and think for a minute, to look around and see the world for what it really is, to get them to cultivate some empathy, then maybe we could start to see a reversal of toxic male culture. What I learned was that it’s hard enough to get men to consider feminism at all let alone to consider challenging their own behavior.

Once you start to get too radical, most men shut down or lash out against it. A few really do embrace it, and that’s something I hold on to—that there are some men out there who are thoughtful enough, and self-reflective enough, and honest enough to internalize the hard truths—but I also realize that most men will never be genuine allies. In fact, most so-called radical men have proven that they are not only incapable of understanding the radical feminist analysis of gender but that they will actively fight against women who espouse it.

The liberal approach to activism is disheartening because it constantly conditions activists to keep working to build an impossible mass movement, and it keeps people hopeful that this can actually happen if they keep spending time and resources on it.

We talk to men about the violence, give them all the evidence they need, and it’s still like trying to drill a hole through a brick wall. I could just as easily take a more passive approach when talking to men and cut them some slack because patriarchy and masculinity do cause men suffering, but last time I checked, emotionally and psychologically mature adults don’t ignore or gloss over the hard truths. Instead those hard truths need to be faced, and men have no excuse to stay passive on this.

Genuine alliance with women means prioritizing the goals of liberation as they are articulated by women and for women, no matter the insecurity and defensiveness men may feel.

As a radical political person of color, I do not accept surface-level activism against white supremacy and privilege. I see the impact of racist oppression in and on my community every single day, and it would be antithetical to my interest in the preservation of my people to avoid engaging with racist culture on a radical level. The oppression of my people needs to end by any means necessary, and this includes the end of the social construction of race.

I wrote an article critiquing white backlash against militant anti-racism, and of course I received still more white backlash. I believe that some white people will agree with me and I hope this is true for pro-feminist alliance with women as well.

Even at my young age I feel that I have spent a long time trying to find the right way to tell men the truth of the widespread violence that women face, but it seems as though the violence is only increasing. I can only imagine the road that some of the women here have walked and the frustration they feel in seeing the violence continue and grow exponentially.

It’s too much. The radical analysis is needed. The situation is urgent and getting worse by the day and I feel like it oftentimes takes so long to educate men and get them to do something, anything.

Some have said to me that I’m impatient. I say I’m fed up. So many men have sided with the violence of this culture and have made themselves the enemy of women and their genuine liberation. And this is pretty simple to me – if a man is an enemy of women, then he is an enemy of mine. Men need to be told, regardless of whether or not they want to hear it, that nothing less than the complete dismantling of patriarchy is acceptable, and men who don’t declare their allegiance to women have sided with the oppressors and they should be treated as such.

Men must try and understand what it takes to become real allies – constant self-critique, checking our privilege, and becoming mindful and aware of when our socialization is causing us to behave in abusive ways. We need to deconstruct this socialized person we’ve been conditioned to become and discover who we are as human beings.

I’ve been told that ultimately men aren’t ready to make comprehensive personal and political changes and to dismantle male culture, and I say so what? It’s ridiculous to think how many men will reject the simple suggestion that they try to become decent human beings. You can’t argue with a person like that. Meanwhile, women are raped on public transportation while the driver looks on and does nothing. A girl is raped in class and the teacher does nothing about it. Women are locked in basements for a decade, or enslaved or beaten or killed. At what point do we as men admit that men hate women and want to harm them?

When do we as men prioritize the safety, integrity and autonomy of women and give men the ultimatum: either you’re with women or you’re against them.

If you want to look at this from the perspective of approaching men in a way that encourages them to engage with us, rather than shutting down and ignoring us, then I can understand that. Sometimes you need to meet people where they are so you can increase the chance of them actually listening and considering what you have to say. This is a long process and oftentimes it takes several intense conversations on these issues with the same men over a period of time to get it to click. Sadly, we don’t always have that kind of time, and most men wouldn’t take the time anyway.

I think it’s important to focus our efforts on constantly engaging and challenging men on their abuse and misogyny and demonstrating to men who insist on continuing that abuse that they will be met with resistance. We will put an end to their abuse using whatever means we have to. They are the ones who cannot be reasoned with, and force is the only language they understand.

A crucial aspect of genuine alliance with women is that it’s our responsibility to educate other men, not women’s responsibility. Saying it’s a women’s issue ignores the perpetrator. It is unfair to leave this work to women who daily endure the onslaught of patriarchal violence. Women have a right to organize away from men, and to demand that we take responsibility for our actions. No, most of us men did not ask for this kind of world. And no, most of us didn’t play an integral part in constructing it. But because we are socialized into it as members of the dominant class; because we are conditioned to use our genitals as weapons against women; and because we are rewarded for doing so, we must do the hard work of separating ourselves from this unfortunate set of affairs and confronting men who refuse to do the same. What do we value more—privilege or justice? Privilege may be comfortable for a while, maybe even for a long time, but eventually it results in the same kind of horrible state of affairs that the planet is currently enduring.

I have had some success presenting this issue to men in the following manner: what does it mean to live in a culture so oppressive to women that they have a good reason to hate us? What does it mean for us that every woman with whom we come into contact can legitimately consider us a potential rapist or batterer? Is this the kind of world we want to live in— a world in which every relationship we have with women is fraught with the anxiety of being perceived as violent simply for being a man? Personally, I do not want to live in this kind of world.

Men need to be given the radical perspective, or else we are simply training them to be ineffective in addressing the problem we claim to care so much about. Just as in radical environmentalism where we base strategy and tactics on the numbers we have so we can be most effective with those numbers, we should do the same with radical pro-feminist education of men. We leverage force against male supremacy and teach each other how to become more complete human beings, how to build loving and nurturing communities, and how to abandon the pathology central to our abuse. This work hasn’t ever been and won’t ever be easy, but it’s necessary and we have a planet and its community of life to save.

Time is short. We should not be prepared to accept any more of this violence. We have a responsibility to ourselves, our loved ones, and future generations to end the violence or die trying.

Thank you.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 1, 2013 | Male Violence

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

I wish this was just a nightmare. My friend is gone and I want her back. She was killed several weeks ago—violently, sadistically, suddenly—and for several weeks I’ve been crying. My head keeps shaking. I whisper to myself: “No. No. No.” Over and over. More than anything else right now, I want this to not be real. But it is the victim herself who would have been the first to remind me: men’s violence against women, the cruelty of this culture, is all too real.

The pain of the world has come home. What words could do it justice? I dredged some up to speak at her funeral, but even then this tragedy felt like a bad dream. It still does.

Just one night before her death, we were making dinner plans for the coming week. Just a few days before that, we were on the phone expressing how much we’ve missed one another. “I’m listening to Regina Spektor and thinking of you,” I said. “Aw, thank you for thinking of me,” she said. “I’d love to see you soon.”

After one unfathomable instance, after one piece of the most horrible of news, our plans are shattered, our relationship gone, my heart broken.

Jessie and I met because we both wanted to change the world; because we both believed that, in the words of a feminist writer we mutually admired, “there are certain kinds of pain that people should not have to endure.”

With her easy smile, a lot of laughter, and a propensity to start so many deeply profound conversations in one sitting, Jessie was a gust of wonder, passion, and beauty. She asked the big questions and, as best she could, tried to live out the answers every day. Her wish was only for others to try, too.

The personal and political were inseparable for Jessie. She was at once a musician, an activist, a daughter, and a friend. She was so much more than any one title could describe. And every aspect of who she was depended on the other; their coming together is what made her life as rich as it was, what made her as dynamic a person as she was, what moved her to change her corner of the world, as she did.

Together, we cooked, we walked in the woods, we talked politics, we talked relationships, we made music, we did activism. We were sternly serious and blissfully silly.

Jessie would sit at the piano and let the music of her life release. She asked me to sing along, which I feebly did. Meanwhile, not so feebly, I stood back and witnessed in awe the undeterred passion flowing out of my friend’s throat and fingertips. It gave me shivers and put tears in my eyes.

Her voice still thunders in my mind. Her songs still have me mesmerized. Her honest longing for justice still humbles me. Her courage in fighting for it still shows me a way to live my life.

Like so much that is alive and beautiful in this world, Jessie was stolen from us. She was a flame snuffed out by the very violence she strived to stop. She was vanished by hands of destruction: a fate Jessie firmly stood against when faced by vulnerable people and a vulnerable planet; a fate that came, in its unspeakable horror, to take her from her safest place, on some random morning.

It’s hard—near impossible—to piece together letters that come close to spelling the magnitude of how wrong this all is. The contrast of her life—which, in her last days, she said explicitly she was loving—and her death—which was cruel beyond sane human comprehension—is staggering. It is heart-breaking.

What can I do with this broken heart? Try as I may, wish as I might, nothing—not the recounting of memories, not the consoling conversations, not the longest of cries, not the steadfast declarations of activism, not the time spent with those who have loved her most and remind me of her most—will bring her back. So, what to do?

If Jessie’s life was made of music, she’d tell me to just keep singing along. She’d tell me, in the simple, honest terms she was so fond of, to simply keep trying; to try at life. As long as I’ve known her, I’ve been better for it. I’ve been encouraged to ask more questions, to be more loving, to sing more and worry less. Why stop now?

Little is as sobering as death. Its lesson is basic: take nothing for granted.

What good is this lesson without my friend? There’s no solace here, just truth in the most truthful sense; the truth that breaks hearts and buoys them.

The truth is I miss Jessie; I want her to be here. The truth is I’m still alive and I have to go on. The truth is I have, at every moment, the choice to embody the wonder and beauty and passion that she embodied.

What I can’t do—and will not do—is forget. Jessie, in life or death, cannot be distilled to a thirty-second news story. She is not just some girl from some small town whom some tragic thing happened to; the once living, now deceased, occasionally remembered. She is not just another victim with a fate too sad to mention.

This dissociating, this forgetting, is what allows us to carry on, quiet and complacent, in the face of glaring and devastating injustice. It is what allows the perpetrators to carry on, too.

The casualties of this culture far outnumber those who survive it. Each one has a story; friends and family in mourning; dreams and passions forever lost.

I want to tell Jessie’s story forever. I want to tell every story of every stolen life as much as I possibly can. I can’t forget Jessie—her laugh, her music, her political vigor, her sitting across the table from me on that night of the full moon—even if I wanted to. I can’t forget the hollow her death has created within me and within this world.

So, what do we do? What do we who love life and love justice and love Jessie do now? First we mourn; then we fight. And all the while, we keep the flames of our love alive: for each other, for this planet, for you, Jessie.

It is utterly stunning how, within the subtleties of a single relationship, we can find something so blazingly true and real and beautiful as to see in it the love that is the fabric of our world; a love worth living and dying for. When those subtleties, and the relationship itself, are stolen from us, it is the meaning of the whole world that shakes beneath us and, eventually, guides us forward. Such is precisely how precious life is.

As her father said, “Jessie’s death crystallizes things. There is a war between forces of life and death. We can either let a small group of people fight it out while the rest of us sit by, or we can get in there.”

Jessie’s kindness radiates still. Jessie’s fight is unfinished. To honor our dear friend, let us now love deeply, defend fiercely, and put an end to violence against women and the culture which fosters it.

I love you, Jessie, and I miss you more than words can explain. I had more to learn from you, more to experience alongside you, more love to give you.

First I’ll mourn. Then I’ll fight. All the while, I’ll love you.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 28, 2013 | Gender

By John Stoltenberg

This article was originally published by Feminist Current, and is republished here with permission from the author.

I understand—I really do—why a lot of people raised to be a man are seeking a gendered sense of self that is separate and distinct from all that has been called out lately as toxic masculinity. These days a penised person* would have to be really clueless not to notice all the manhood-proving behaviors that have been critiqued as hazardous to well-being (one’s own and others’). However much that penised person accepts the mounting critique of standard-issue masculinity, he might reasonably be wondering what manhood-authenticating behaviors are exempt from it: What are the ways to “act like a man” that definitively keep one from being confused with “men behaving badly”? Or, put more personally: What exactly does one do nowadays to inhabit a male-positive gendered identity that feels—and is—worthy of respect (by oneself and others)?

At the same time—as if in an alternate universe—there are legions of people raised to be a man who have been exposed to the criticism of masculinity but are rejecting and resisting the critique with all their might, almost at a cellular level, the way a body’s immune system generates antibodies to fend off an invading infection. For these penised people, criticism of any masculinity is experienced as an attack on all masculinity. Simmering resentment, eruptive anger, and backlash are but a few symptoms of their abreaction. What’s going on inside—where they feel their authentic “This is who I am”—is a life-and-death struggle against what they perceive portends personal annihilation.

For the sake of clarity, I’ll name these two characterizations Reformers and Conservers. Of course these are not the only segments of the penised population. But I’m going to assume they are both prominent enough that most readers will recognize them in broad outline. And I’m going to assume, further, that most readers place some sort of valuation on these two personas. One is better than the other, most readers are probably thinking. One is Good Guy and one is Bad Guy. And no matter whether you believe that Reformers are the real good guys or Conservers are the real good guys, what will likely be on your mind is that one does a superior job of “doing masculinity” while the other does an inferior job.

Notice how the better-than/worse-than categorization scheme comes mentally into play? It kicks in like a habit whenever one’s acculturated higher cortex is presented with any question having to do with manhood. The brain has been conditioned since childhood to perceive the social gender identity manhood through a lens of better than/worse than. It’s how we all learned to experience the identity, and it’s how we all know to recognize “who’s the man there.” It’s also how some of us embody credible manhood if and when we can, and it’s what all of us try to keep safe from if and when we can’t. Because this interior superior/inferior typology is intractably linked to interactional cognition of the gender identity manhood, it’s no wonder that neither Resisters nor Conservers get round to thinking about the template very critically.

But we must do that. We actually must. Our lives depend upon it.

For reasons implicit in my opening paragraph about Reformers, the notion of “healthy masculinity” has caught on in many circles the past few years. People convene about it, organize and workshop about it, tweet and blog about it, and in general work conscientiously at making the concept mean something viable and valuable that will fill an emptiness in Reformers’ lives—the yawning void left when, beginning a few decades ago, “He acts just like a man” began to shift from laudatory to derogatory.

Conservers, of course, don’t think there’s anything unwell about masculinity at all. And they definitely believe that masculinity ought not be impugned—as, in truth, it is—by the expression “healthy masculinity.” Imagine how a patient in a cancer ward would feel if a newly enlightened roommate began rejoicing about having healthy cancer. Probably offended. Maybe pissed off. Similarly a Conserver will never be persuaded that the masculinity he aspires to and embodies is unhealthy, or an affliction of some sort. Instead, the Conserver will regard the innuendo of “healthy masculinity” as itself a form of life-threatening attack.

Now, call me crazy, but I don’t see much long-term promise in talking only to Reformers or only to Conservers. And I certainly see no advantage in sending a message—“healthy masculinity”—that is sure to exacerbate the gender anxiety of anyone who doesn’t believe that subscribing to analog masculinity somehow makes a person sick. Shutting off communications with Conservers from the get-go by talking of “healthy and unhealthy masculinity” is at best vain and counterproductive and at worst inflammatory. Numerically Conservers represent a lot of penised people; they probably represent more than Reformers, who are still a minority inside the Conserver-dominant culture. But besides being a triggering turnoff to Conservers, there’s an even bigger problem with talking of “healthy masculinity”: It’s based on a well-meaning but ultimately faulty premise. It’s not the right fix for the problem. It’s actually a “cure” that reinvigorates a “disease.”

Many folks of goodwill want whatever’s wrong with the social gender identity manhood to be fixed comprehensively. Their hope is that the fix will avert all those male-gender-identity flare-ups that are well known to cause collateral damage. They want to live in a world where there is no need to be afraid of someone simply because they were born penised and socialized to be a man. In short, they want more harmony among human beings than we are presently accustomed to on the planet.

But here’s the rub: Any movement or campaign to remedy manhood cannot itself replicate the better-than/lesser-than oneupsmanship upon which—inside everyone’s head—manhood is definitionally predicated. Every time our acculturated brains want to identify certain penised people who are “doing masculinity” superiorly, we are reactivating the same mental scripts that were imprinted in us when we watched, or participated in, our earliest mano-a-mano fights. Someone was the victor. Someone was the loser. That was the way we learned the meaning of “manhood.” And that winner/loser, dominant/subordinate definitional prototype does not just vanish into thin air.

Instead we have to figure out a way to retrain brains, and reframe what the problem is precisely. To explain what I mean, I’m going to digress a bit and talk about what’s known as bystander-intervention training.

Basically bystander-intervention training is a program to equip penised people with communication skills, empathy, emotional intelligence, relational tactics, and a sense of personal agency to intervene when they see another penised person about to commit a sexual assault. Bystander-intervention training is widely regarded as one of the most effective means of primary sexual-assault prevention in social situations such as bars and parties where there are likely to be observers.

A big part of the program is teaching trainees (who tend to be Reformers) how to address one or several other penised people (often but not always Conservers) in a way that will effectively interrupt a probable assault-in-progress, create an exit option for a probable victim, and—here’s the tricky part—not precipitate a cockfight with the probable perp.

There are many worthy aspects of bystander-intervention training but the one I want to focus on is this: It is practice acting out of one’s moral agency without trying to prove one’s manhood. This is a discipline that is learnable, replicable, and rememberable. One reason a trainee knows the discipline is important is that he knows darn well what will happen if he does try to prove his manhood in such a situation: The contretemps will turn to combat of one sort or another, because the very act of trying to demonstrate one’s own manhood vis-à-vis another penised person will fuel the other person’s manhood-demonstrating responses (which are fired up already, as evidenced by the sexual-assault-in-progress).

And when a trainee overcomes his own anticipatory dread of what might happen to him if he intervenes—when in real life he actually does step up and say or do something that interrupts what might have ended harmfully—he learns another powerful lesson: “I did that. I said that. I stopped that.” Put another way: “I acted out of my own moral agency and I can take personal responsibility for the consequence of that action.”

Of course, those words are not literally what runs through the ex-bystander’s mind. But there’s a distinct experience captured in that moment. It’s the experience of acting out of one’s conscience and being who one is.

I submit that when we connect the dots of moments like that—real-time instances of embodied ethics and accountability—a new picture of the problem will emerge alongside a new recognition of the solution.

Learning how to act out of one’s moral agency with consistency—how to tap into one’s capacity for ethical choice-making in a way that other people can come to expect one to do—is not a gendered behavior (it doesn’t come with any particular plumbing), nor is it a gendering behavior (it doesn’t make someone more anything except more human).

Another digression.

Ever notice how frequently the words “Real men don’t…” appear in male-pattern-violence** prevention campaigns? “Real men don’t buy girls.” “Real men don’t hit women.” “Real men don’t rape.” The list goes on. “Real men don’t…” has become a Reformers’ mantra. (No pun intended.)

But there are three problems with “Real men don’t…” The first is that the trope conceals and obscures the actual dynamic between manhood-proving and male-pattern violence. Men rape in order to experience themselves as real men. Men hit women in order to show they are the man there. Men buy prostituted women and children in order to get off like a real man—the payoff promised and promoted by pornography. (And that’s the functional purpose of the so-called money shot: to show a penised person ejaculating in circumstances that authenticate him as a real man.)

The second problem with “Real men don’t…” follows from the first: It is a meaningless message to the audience it is intended to reach. Announcing that “real men” don’t commit male-pattern violence is utterly unpersuasive to anyone for whom doing male-pattern violence makes him feel like a “real man.”

And the third problem with “Real men don’t…” is that while it preaches to the Reformer choir, it sends an unhelpful message. It keeps moral choice-making locked into gender identity rather than allowing it to express moral identity. It keeps “who I am here and now” inside the straightjacket of “I am nobody if not a man.” Moreover, by evoking the construct real manhood, “Real men don’t…” retriggers and reifies the anxiety that pervaded every penised person’s upbringing: “Am I a real-enough boy?” “Am I real-enough man?” “How can I convince myself and others?”

That last problem with “Real men don’t…” points to the fundamental problem with the idea of “healthy masculinity.” Talk about “healthy masculinity” sounds good—at least to the ears of Reformers and people who wish to love them. It offers individual respite from the incessant headlines about men’s crimes against women and other men; it functions as a feel-good exemption from being implicated. It helps one belong to a tribe of other “healthy masculinity” devotees—a comfortable camaraderie in which one can feel safe from all those perilous challenges to one’s manhood elsewhere.

And yet the idea of “healthy masculinity” does not liberate conscience from gender. “Healthy masculinity” keeps conscience gendered. And it’s not.

Conscience is human. Human only. And only human.

John Stoltenberg has explored the distinction between gender identity and moral identity in two books: “Refusing to Be a Man: Essays on Sex and Justice“ and “The End of Manhood: Parables on Sex and Selfhood“ His new novel, GONERZ, projects a radical feminist vision into a post-apocalyptic future. John conceived and creative-directed the acclaimed “My strength is not for hurting” sexual-assault-prevention media campaign, and he continues his communications- and cause-consulting work through media2change. He tweets at @JohnStoltenberg and @media2change.

Two notes on usage:

* I began using the term “penised person” in The End of Manhood in order to keep clear that so-called anatomical sex is merely a trait (like eye or hair color), not a ground of being.

** And I use the term “male-pattern violence” instead of the more common (but less precise) “gender-based violence.”

From Feminist Current: http://feministcurrent.com/7868/why-talking-about-healthy-masculinity-is-like-talking-about-healthy-cancer/