Aric McBay

Originally published at inthewake.org

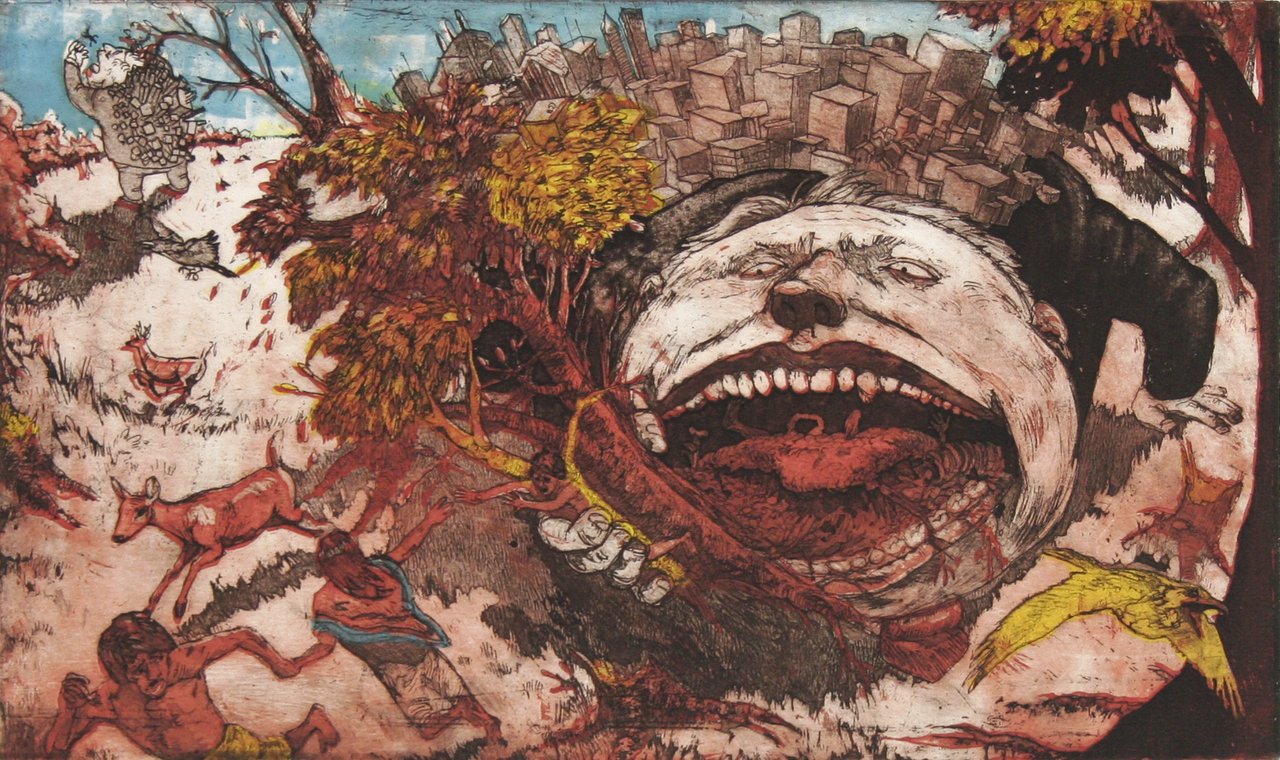

When some people hear that we want to “end civilization” they initially respond negatively, because of their positive associations with the word “civilization.” This piece is an attempt to clarify, define and describe what I mean by “civilization.”

One dictionary definition1 reads:

civilization

- a society in an advanced state of social development (eg, with complex legal and political and religious organizations); “the people slowly progressed from barbarism to civilization” [syn: civilisation]

- the social process whereby societies achieve civilization [syn: civilisation]

- a particular society at a particular time and place; “early Mayan civilization” [syn: culture, civilisation]

- the quality of excellence in thought and manners and taste; “a man of intellectual refinement”; “he is remembered for his generosity and civilization” [syn: refinement, civilisation]

The synonyms include “advancement,” “breeding,” “civility,” “cultivation,” “culture,” “development,” “edification,” “education,” “elevation,” “enlightenment,” “illumination,” “polish,” “progress,” and “refinement”. Of course. As Derrick Jensen asks, “can you imagine writers of dictionaries willingly classifying themselves as members of ‘a low, undeveloped, or backward state of human society’?”

In contrast, the antonyms of “civilization” include “barbarism,” “savagery,” “wilderness,” and “wildness.” These are the words that civilized people use to refer to those they view as being outside of civilization—in particular, indigenous peoples. “Barbarous,” as in “barbarian,” comes from a Greek word, meaning “non-Greek, foreign.” The word “savage” comes from the Latin “silvaticus” meaning “of the woods.” The origins seem harmless enough, but it’s very instructive to see how civilized people have used these words2:

barbarity

- The quality of being shockingly cruel and inhumane [syn: atrocity, atrociousness, barbarousness, heinousness]

- A brutal barbarous savage act [syn: brutality, barbarism, savagery]

savagery

- The quality or condition of being savage.

- An act of violent cruelty.

- Savage behavior or nature; barbarity.

These associations of cruelty with the uncivilized are, however, in glaring opposition to the historical record of interactions between civilized and indigenous peoples.

Let us take one of the most famous examples of “contact” between civilized and indigenous peoples. When Christopher Columbus first arrived in the “Americas” he noted that he was impressed by the indigenous peoples, writing in his journal that they had a “naked innocence … They are very gentle without knowing what evil is, without killing, without stealing.”

And so he decided “they will make excellent servants.”

In 1493, with the permission of the Spanish Crown, he appointed himself “viceroy and governor” of the Caribbean and the Americas. He installed himself on the island now divided between Haiti and the Dominican republic and began to systematically enslave and exterminate the indigenous population. (The Taino population of the island was not civilized, in contrast to the civilized Inca who the conquistadors also invaded in Central America.) Within three years he had managed to reduce the indigenous population from eight million to three million. By 1514 only 22,000 of the indigenous population remained, and after 1542 they were considered extinct.3

The tribute system, instituted by [Columbus] sometime in 1495, was a simple and brutal way of fulfilling the Spanish lust for gold while acknowledging the Spanish distaste for labor. Every Taino over the age of fourteen had to supply the rulers with a hawk’s bell of gold every three months (or, in gold-deficient areas, twenty-five pounds of spun cotton; those who did were given a token to wear around their necks as proof that they had made their payment; those did not were … “punished” – by having their hands cut off … and [being] left to bleed to death.4

More than 10,000 people were killed this way during Columbus’ time as governor. On countless occasions, these civilized invaders engaged in torture, rape, and massacres. The Spaniards

… made bets as to who would slit a man in two, or cut off his head at one blow; or they opened up his bowels. They tore the babes from their mother’s breast by their feet and dashed their heads against the rocks … They spitted the bodies of other babes, together with their mothers and all who were before them, on their swords.5

On another occasion:

A Spaniard … suddenly drew his sword. Then the whole hundred drew theirs and began to rip open the bellies, to cut and kill – men, women, children and old folk, all of whom were seated off guard and frightened … And within two credos, not a man of them there remains alive. The Spaniards enter the large house nearby, for this was happening at its door, and in the same way, with cuts and stabs, began to kill as many as were found there, so that a stream of blood was running, as if a number of cows had perished.6

This pattern of one-way, unprovoked, inexcusable cruelty and viciousness occurred in countless interactions between civilized and indigenous people through history.

This phenomena is well-documented in excellent books including Ward Churchill’s A Little Matter of Genocide: Holocaust and Denial in the Americas, 1492 to the Present, Kirkpatrick Sale’s The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy, and Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Farley Mowat’s books, especially Walking on the Land, The Deer People, and The Desperate People document this as well with an emphasis on the northern and arctic regions of North America.

There is also good information in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States and Voices of a People’s History of the United States. Eduardo Galeando’s incredible Memory of Fire trilogy covers this topic as well, with an emphasis on Latin America (this epic trilogy reviews numerous related injustices and revolts). Jack D Forbes’ book Columbus and Other Cannibals: The Wetiko Disease of Exploitation, Imperialism and Terrorism is highly recommended. You can also find information in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, although I often disagree with the author’s premises and approach.

The same kind of attacks civilized people committed against indigenous peoples were also consistently perpetrated against non-human animal and plant species, who were wiped out (often deliberately) even when civilized people didn’t need them for food; simply as blood-sport. For further readings on this, check out great books like Farley Mowat’s extensive and crushing Sea of Slaughter, or Clive Ponting’s A Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations (which also examines precivilized history and European colonialism).

With this history of atrocity in mind, we should (if we haven’t already) cease using the propaganda definitions of civilized as “good” and uncivilized as “bad” and seek a more accurate and useful definition. Anthropologists and other thinkers have come up with a number of somewhat less biased definitions of civilization.

Nineteenth century English anthropologist E B Tylor defined civilization as life in cities that is organized by government and facilitated by scribes (which means the use of writing). In these societies, he noted, there is a resource “surplus”, which can be traded or taken (though war or exploitation) which allows for specialization in the cities.

Derrick Jensen, having recognized the serious flaws in the popular, dictionary definition of civilization, writes:

I would define a civilization much more precisely, and I believe more usefully, as a culture – that is, a complex of stories, institutions, and artifacts – that both leads to and emerges from the growth of cities (civilization, see civil: from civis, meaning citizen, from latin civitatis, meaning state or city), with cities being defined – so as to distinguish them from camps, villages, and so on – as people living more or less permanently in one place in densities high enough to require the routine importation of food and other necessities of life.

Jensen also observes that because cities need to import these necessities of life and to grow, they must also create systems for the perpetual centralization of resources, yielding “an increasing region of unsustainability surrounded by an increasingly exploited countryside.”

Contemporary anthropologist John H Bodley writes: “The principle function of civilization is to organize overlapping social networks of ideological, political, economic, and military power that differentially benefit privileged households.”7 In other words, in civilization institutions like churches, corporations and militaries exist and are used to funnel resources and power to the rulers and the elite.

The twentieth century historian and sociologist Lewis Mumford wrote one of my favourite and most cutting and succinct definitions of civilization. He uses the term civilization

… to denote the group of institutions that first took form under kingship. Its chief features, constant in varying proportions throughout history, are the centralization of political power, the separation of classes, the lifetime division of labor, the mechanization of production, the magnification of military power, the economic exploitation of the weak, and the universal introduction of slavery and forced labor for both industrial and military purposes.8

Taking various anthropological and historical definitions into account, we can come up with some common properties of civilizations (as opposed to indigenous groups).

- People live in permanent settlements, and a significant number of them in cities.

- The society depends on large-scale agriculture (which is needed to support dense, non-food-growing urban populations).

- The society has rulers and some form of “aristocracy” with centralized political, economic, and military power, who exist by exploiting the mass of people.

- The elite (and possibly others) use writing and numbers to keep track of commodities, the spoils of war, and so on.

- There is slavery and forced labour either by the direct use of physical violence, or by economic coercion and violence (through which people are systematically deprived of choices outside the wage economy).

- There are large armies and institutionalized warfare.

- Production is mechanized, either through physical machines or the use of humans as though they were machines (this point will be expanded on in other writings here soon).

- Large, complex institutions exist to mediate and control the behaviour of people, through as their learning and worldview (schools and churches), as well as their relationships with each other, with the unknown, and with the nature world (churches and organized religion).

Anthropologist Stanley Diamond recognized the common thread in all of these attributes when he wrote; “Civilization originates in conquest abroad and repression at home”.9

This common thread is control. Civilization is a culture of control. In civilizations, a small group of people controls a large group of people through the institutions of civilization. If they are beyond the frontier of that civilization, then that control will come in the form of armies and missionaries (be they religious or technical specialists). If the people to be controlled are inside of the cities, inside of civilization, then the control may come through domestic militaries (ie, police). However, it is likely cheaper and less overtly violent to condition of certain types of behaviour through religion, schools or media, and related means, than through the use of outright force (which requires a substantial investment in weapons, surveillance and labour).

That works very effectively in combination with economic and agricultural control. If you control the supply of food and other essentials of life, people have to do what you say or they die. People inside of cities inherently depend on food systems controlled by the rulers to survive, since the (commonly accepted) definition of a city is that the population is dense enough to require the importation of food.

For a higher degree of control, rulers have combined control of food and agriculture with conditioning that reinforces their supremacy. In the dominant, capitalist society, the rich control the supply of food and essentials, and the content of the media and the schools. The schools and workplaces act as a selection process: those who demonstrate their ability to cooperate with those in power by behaving properly and doing what they’re told at work and school have access to higher paying jobs involving less labour. Those who cannot or will not do what they’re told are excluded from easy access to food and essentials (by having access only to menial jobs), and must work very hard to survive, or become poor and/or homeless. People higher on this hierarchy are mostly spared the economic and physical violence imposed on those lower on the hierarchy. A highly rationalized system of exploitation like this helps to increase the efficiency of the system by reducing the chance of resistance or outright rebellion of the populace.

The media’s propaganda systems have most people convinced that this system is somehow “natural” or “necessary”—but of course, it is both completely artificial and a direct result of the actions of those in power (and the inactions of those who believe that they benefit from it, or are prevented from acting through violence or the threat of violence).

In contradiction to the idea that the dominant culture’s way of living is “natural,” human beings lived as small, ecological, participatory, equitable groups for more than 99% of human history. There are a number of excellent books and articles comparing indigenous societies to civilization:

- Chellis Glendinning’s My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery from Western Civilization (Shambhala, 1994). You can read an excerpt of the chapter “A Lesson in Earth Civics.” She has also written several related books, including When Technology Wounds: The Human Consequences of Progress (Morrow, 1990).

- Marshall Sahlin’s Stone Age Economics (Adline, 1972) is a detailed classic in that same vein. You can read his essay “The Original Affluent Society.”

- Anthropologist Stanley Diamond’s book In Search of the Primitive: A Critique of Civilization (Transaction Publishers, 1987).

- Richard Heinberg’s essay “The Primitivist Critique of Civilization.”

These sources show there were healthy, equitable and ecological communities in the past, and that they were the norm for countless generations. It is civilization that is monstrous and aberrant.

Living inside of the controlling environment of civilization is an inherently traumatic experience, although the degree of trauma varies with personal circumstance and the amounts of privilege different people have in society. Derrick Jensen makes this point very well in A Language Older than Words (Context Books, 2000), and Chellis Glendinning covers it as well in My name is Chellis.

Endnotes

1. Definition of “civilization” is from WordNet R 2.0, 2003, Princeton University

2. Definitions of “barbarity” and “savagery” are from The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, 2000, Houghton Mifflin Company.

3. I owe many of the sources in this section to the research of Ward Churchill. The figure of eight million is from chapter six of Essays in Population History, Vol I by Sherburn F Cook and Woodrow Borah (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). The figure of three million is from is from a survey at the time by Bartolome de Las Casas covered in J B Thatcher, Christopher Columbus, two volumes (New York: Putnam’s, 1903-1904) Vol 2, page 384 ff. They were considered extinct by the Spanish census at the time, which is summarized in Lewis Hanke’s The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America (Philapelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1947) page 200 ff.

4. Sale, Kirkpatrick. The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1990) page 155.

5. de Las Casas, Bartolome. The Spanish Colonie: Brevisima revacion (New York: University Microfilms Reprint, 1966).

6. de Las Casas, Bartolome. Historia de las Indias, Vol 3, (Mexico City: Fondo Cultura Economica, 1951) chapter 29.

7. Bodley, John H, Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States and the Global System. Mayfield, Mountain View, California, 2000.

8. Mumford, Lewis. Technics and Human Development, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1966, page 186.

9. Diamond, Stanley, In Search of the Primitive: A Critique of Civilization, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, 1993, page 1.

Photo by Henry Chen on Unsplash

Great article

This is a great essay and one can leave it as it is or use it as starting point of a discussion about possible visions, strategies, and personal consequences like lifestyle and social/political activities.

Such discussions have happened before and though many were exhausting and fruitless, some helped the participants to change or redefine their values and attitudes.

Without a useful definition of civilization, no-one knows what it is. Hence neither the author of the article, nor the commentators, know that they are talking about the blossoming then shrivelling of human understanding, manifested as the rise then fall of a dominant society.

Indeed, they are taking delight in the shrivelling of their communal understanding, which of course includes their own understanding.

“Without a useful definition of civilization, no-one knows what it is”.

But it’s defined right at the beginning of the article???

Your comment is nonsensical: “they are taking delight in the shrivelling of their communal understanding, which of course includes their own understanding.”

So, ‘they are delighting in the shrivelling of their understanding, which includes their understanding’ …ok.

The one who doesn’t know what they’re talking about, is *you*.

Your claimed definition is not a definition.

A civilisation is the blossoming then shrivelling of the shared understanding that is a society.

In one sentence I have revealed both what a society and a civilisation is.

Please do not hesitate to refute my claim, otherwise I will believe you cannot refute it.

Your words are noise and have no sensible meaning.

Your words about civilisation are not a definition but a vague impression.

A civilisation is the blossoming then shrivelling of the shared understanding that is a society.

Please refute my claim otherwise I will believe you cannot.

You can disemble all you want, it makes no difference to the truth.

If a ‘shared understanding’ includes the enslavement and murder of other people in their own land, then such a ‘civilization’ is sick.

Your words are just the noise of your rage. Either refute the definition of civilisation or confess it may be correct.

“Without a useful definition of civilization, no-one knows what it is.”

Looks like you’ve changed your mind and come up with a definition then (“shared understanding [etc]”.

So we all know what it is, it’s just that you think it’s great – and the author of the article (and most of the commentators) do not think so.

Humanity has been unable to define civilisation until my definition, which has been ignored. The same thing applies to society, which is how humanity exists. As this has been the case for millennia, the question must be, why is this so?

And now there is a useful definition of both, why does humanity not even comment on them? My definitions explain why, which is because society has lost its sanity. Your response, rage, is of course, an insane response. Please note you can prove your sanity by answering how you tell right from wrong. I await your silence.

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” – Aldo Leopold, The Land Ethic

[Reply button not appearing, so submitting new comment.]

Humans managed fine for hundreds of millennia, before the current hierarchies took over, with governments, taxation etc concentrating wealth in the hands of a parasitic owner class.

Western civilization had no sanity to lose. It was always a house of cards from the outset.

Please don’t call me insane or tell me I have “rage” – it does not bolster your position. Lol, “prove your sanity”!

If you like being governed and need their laws to tell you right from wrong, that’s up to you.

A claim is true when it is true. It is unsure what ‘right’ means in this context, but it appears to suggest harsh truth should be ignored.

Knowing right from wrong does not require civilzation, governments, laws etc.

Humanity exists as societies, some of which build civilisations, so it is essential to know what these are to understand humanity. How you recognise right from wrong is your religion, which dictates if you are sane or insane, so it is essential to also recognise what sanity is. You seem to insist upon maintaining ignorance, which is usually a sign of inanity. You can demonstrate you sanity or otherwise, by revealing how you recognise right from wrong. I

See how you attempt to move from the subject of ‘civilization’ to accusing me of being insane…

Why do you keep banging on about religion? Maybe you are a couple of chapters short of a full Bible.

I’m “maintaining ignorance”? Wtf are you on about? And do you mean “inanity” or “insanity”? Make your mind up.

Most sane people (maybe not you) instinctively know right from wrong.

How do *you* recognise right from wrong? Go on, demonstrate you sanity.

You do not know what a civilisation is. You do not know what a society is. You do not know what sanity is. You refuse to accept my simple definitions but cannot refute them. That is you insist upon remaining ignorant, and fly into a rage at the idea you should either refute or acknowledge my definitions. That is, you are not rational. But explaining this to irrational people is futile because they are ruled by their feelings. Just explain what is the most important thing to you. I know and you know this is “You”. And this is insanity.

“You” this, “You” that. You, you, you! Have you heard yourself? You keep saying I “fly into a rage” but that does not make it true. Probably projection, as you are clearly the one who is raging (mad).

All you have left is hurling insults in lieu of a cogent argument.

Your silly definition (after you contradicted yourself by first saying no definition existed) is so pathetic, I thought it hardly worth refuting, but I will do so: civilizations are cultures that create cities, that consume everything around them and then themselves.

All people are ruled by their feelings. It’s only the insane ones, like you, who pretend they are not.