In this excerpt from Ain’t I Woman: Black Women and Feminism, author bell hooks describes the insidious nature of racism and sexism and the links between patriarchy and white supremacy. Understanding this type of analysis is critical to understanding how oppression functions within civilization as a tool of social control. While hooks uses the term “American,” the same analysis applies across much of the world.

Racism and Feminism: The Issue Of Accountability

By bell hooks

American women of all races are socialized to think of racism solely in the context of race hatred.

Specifically in the case of black and white people, the term racism is usually seen as synonymous with discrimination or prejudice against black people by white people.

For most women the first knowledge of racism as institutionalized oppression is engendered either by direct personal experience or through information gleaned from conversations, books, television, or movies. Consequently, the American woman’s understanding of racism as a political tool of colonialism and imperialism is severely limited.

To experience the pain of race hatred or to witness that pain is not to understand its origin, evolution, or impact on world history. The inability of American women to understand racism in the context of American politics is not due to any inherent deficiency in the woman’s psyche. It merely reflects the extent of our victimization.

No history books used in public schools informed us about racial imperialism.

Instead we were given romantic notions of the “new world“ the “American dream.” America as a great melting pot where all races come together as one. We were taught that Columbus discovered America; that “Indians“ was Scalphunters, killers of innocent women and children; that black people were enslaved because of the biblical curse of Ham, that God “himself” had decreed they would be hewers of wood, tillers of the field, and bringers of water.

No one talked of Africa as the cradle of civilization, of the African and Asian people who came to America before Columbus. No one mentioned mass murder of native Americans as genocide, or the rape of native American and African women as terrorism. No one discussed slavery as a foundation for the growth of capitalism. No one describe the forced breeding of white wives to increase the white population as sexist oppression.

I am a black woman. I attended all black public schools. I grew up in the south were all around me was the fact of racial discrimination, hatred, and for segregation. Yet my education to the politics of race in American society was not that different from that of white female students I met in integrated high schools, in college, or in various women’s groups.

The majority of us understood racism as a social evil perpetrated by prejudiced white people that could be overcome through bonding between blacks and liberal whites, through military protest, changing of laws or racial integration. Higher educational institutions did nothing to increase our limited understanding of racism as a political ideology. Instead professors systematically denied us truth, teaching us to accept racial polarity in the form of white supremacy and sexual polarity in the form of male dominance.

American women have been socialized, even brainwashed, to accept a version of American history that was created to uphold and maintain racial imperialism in the form of white supremacy and sexual imperialism in the form of patriarchy. One measure of the success of such indoctrinate indoctrination is that we perpetrate both consciously and unconsciously the very evils that oppress us.

Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name bell hooks, is an American author, professor, feminist, and social activist.

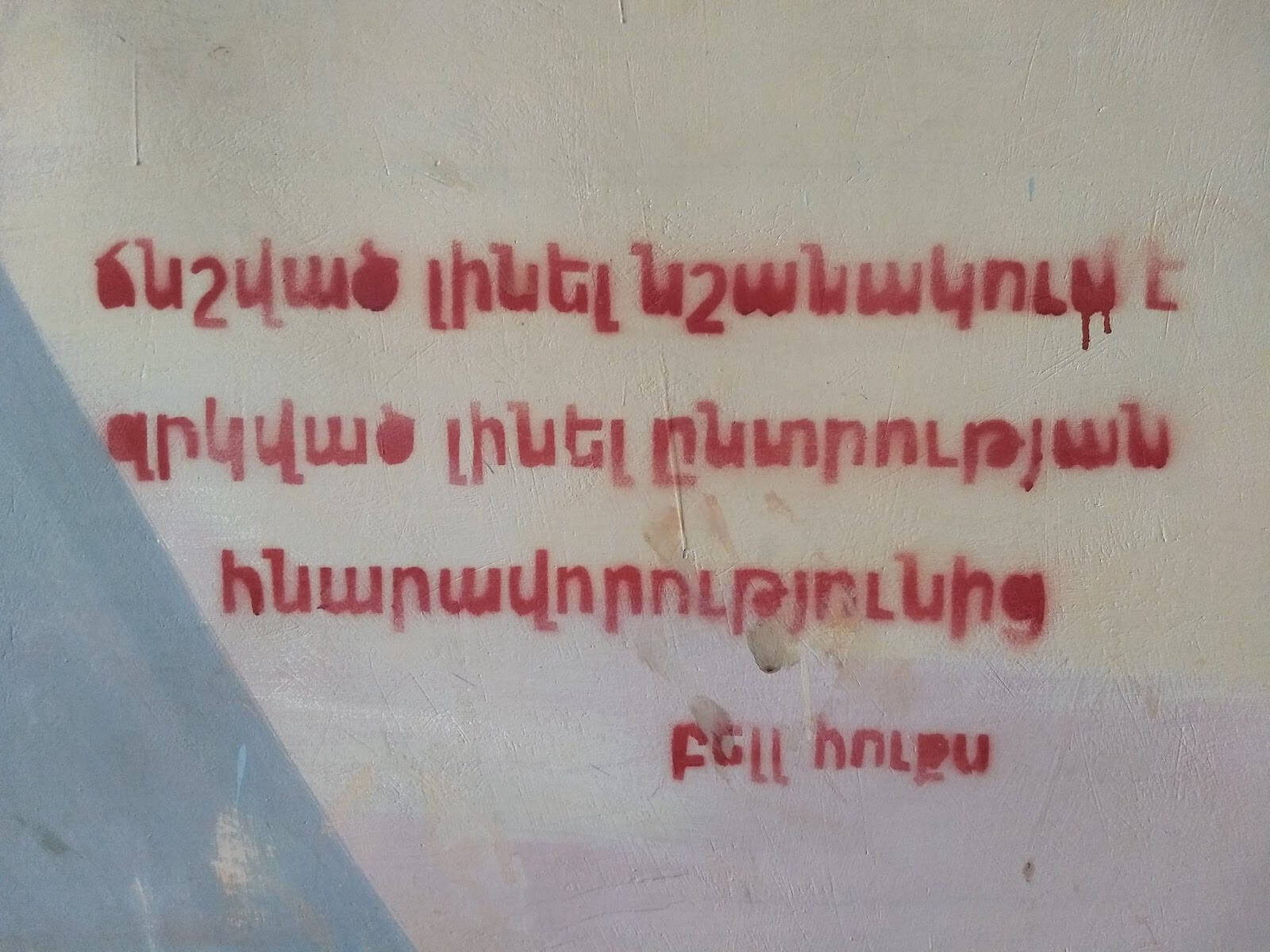

Featured image: Armenian Graffiti in the city of Yerevan. It is a translated quote of the author bell hooks which reads “To be oppressed means to be deprived of your ability to choose.” By RaffiKojian, CC BY SA 4.0.

Three notes:

• “Indians” learned scalping from whites, who did it to them first — and then called the indigenous tribes who responded in kind, “savages.”

• Around 1927, Hitler wrote an unpublished sequel to “Mein Kampf,” in which he cited the American expulsion and decimation of “Indians” as his inspiration for the “final solution” to Europe’s imagined “Jewish problem.”

Before spending a $20 bill, it’s a good idea to write “genocide,” “war criminal,” “Hitler’s prototype,” or something similar over Andrew Jackson’s face — and to remember that his portrait hangs in the Oval Office to this day.

• This is nothing to brag about, but my hometown, San Angelo, TX (also that of civil rights leader, Cecil Williams), began integrating its schools in 1957 — a full 14 years before Dallas, Austin or Houston. They were building the nation’s first campus-style high school, and the school board president, Frank Pool, had the foresight to integrate the new high school (which would serve the entire school district), and to bus all 7th-graders to one of the vacated junior highs. To avoid further disruption, the dozen or so elementary schools and the two public junior highs would remain under de facto, neighborhood segregation.

Four quick anecdotes about that transition:

•Despite quiet grumbling by a few white parents over busing, the integration of 7th grade (named Washington Junior High) produced no racial incidents I’m aware of (I attended during the 1960-61 school year). San Angelo wasn’t forcibly segregated, anyway. It’s creation postdated the Civil War by more than a decade, and one of the city’s founders was a black former soldier from Ft. Concho, the local “buffalo soldier” outpost.

Restaurants and theaters were largely under de facto segregation. But there were no “whites only” or “reserved for colored” signs anywhere in the city, other than the Greyhound Bus station (which followed that policy throughout the South), and on local buses, where the signs were totally ignored.

• 8th- and 9th-grade students attended Blackshear, Edison, and Lee Junior High. Blackshear was all black, Edison was a mix of white and Hispanic, and Lee (which was in my district) was all white — with two exceptions. There was a black boy in the band, and (musicians being more into music than color) he seemed to fit in well.

The black girl, on the other hand, was possibly the most isolated human being I have ever known. She had no friends at school, ate lunch alone, and was so afraid of possibly offending someone that she never spoke in class, or to any of the white girls in school. We shared an algebra class, and when I leaned over one day to ask her a question, she was initially too terrified to speak — as if unsure of the proper etiquette for addressing a male of the dominant social class. I have often wondered what happened to her, where she lived in later life, and what she might have to say, if we met again today.

• Central High was a different story. Blackshear High was closed with the opening of Central, so that all of the city’s black students attended Central for grades 10-12, and accounted for perhaps 6-10% of the student body.

Students were allowed to smoke in two areas, with 20 or so whites (out of a student body of 2000 or so) gathering on the sidewalk in front of the cafeteria, and 3 or 4 blacks (all male) in the area between the science building and the tennis courts.

My science class preceded the afternoon break. And — being dumb enough to smoke, but smart enough not to waste half of my break walking to the cafeteria — I decided to join the black smokers one afternoon. When I approached, they looked at me with disdain. But once we broke the ice, I was readily accepted into the group, and quickly became a regular. We all knew without asking, however, that if one of the black smokers had tried the same thing in front of the cafeteria, he would have neen shunned. Half of the white kids would have been repulsed at the idea of social race mixing, and herd instinct would have governed the rest.

• Much like major league professional sports, Central High had no black athletes for the first 3 years or so, until an exceptional player dared to cross the color line in football. Basketball remained all white until 1963, when the new coach dared to openly recruit 4 black players. There was some grumbling again from a few white parents — including a couple of unhappy letters to the local paper, complaining about their sons having to shower and dress with blacks.

The next year, Central won the state basketball championship, and the city was well on its way to integration.