by DGR News Service | Jul 31, 2019 | Property & Material Destruction, White Supremacy

In mid-July, an armed attack on ICE facilities in Tacoma, Washington took place. Here’s a brief summary of what happened:

Will Van Spronsen… was killed [on July 13th] while carrying out a raid against a migrant concentration camp in Tacoma, Washington State. Van Spronsen is thought to be the first person killed attempting to take direct action against the US deportation system, which for months has faced heavy criticism over its use of concentration camps to break up families and detain migrant children.

The 69-year-old, known as an anti-fascist and campaigner against migrant detention, was shot dead by four police officers as he attempted to set fire to deportation buses stationed at the Northwest Detention Center (NWDC), a few hours after a peaceful protest against the facility had been held.

– Via Freedom News

DGR Response to Armed Attack on ICE Facility

Deep Green Resistance recognizes, first and foremost, that Immigration and Customs Enforcement is nothing more than the paramilitary wing of the settler nation. Tacoma, like all of so-called North America, rests on stolen land – as an illegitimate occupier, this government has no right to establish or enforce imaginary borders across the territory of the Coast Salish people or any other indigenous community.

DGR affirms the struggle against all forms of xenophobia and white supremacy, and we stand in solidarity with those who resist ICE and its glorified ethnic cleansing. Direct action of this kind against the American immigration enforcement is justified and moral.

However, we also affirm the need for strategic, organized resistance that is capable of striking decisive blows against the settler state. Lone-wolf attacks of this nature are unlikely to achieve much beyond the symbolic. While we honor Van Spronsen’s bravery, we encourage activists to evaluate actions like these and consider more effective methods and strategies.

Decisive Ecological Warfare, the strategy of Deep Green Resistance, provides a detailed roadmap for creating and maintaining a militant resistance movement capable of overturning the white supremacist settler state. As aboveground activists, we must work to harness and direct the kind of fury and passion that leads to attacks like these, away from individual expressions of rage and towards organized militancy on behalf of the planet and all oppressed peoples.

by DGR News Service | Jul 22, 2019 | Repression at Home, The Solution: Resistance

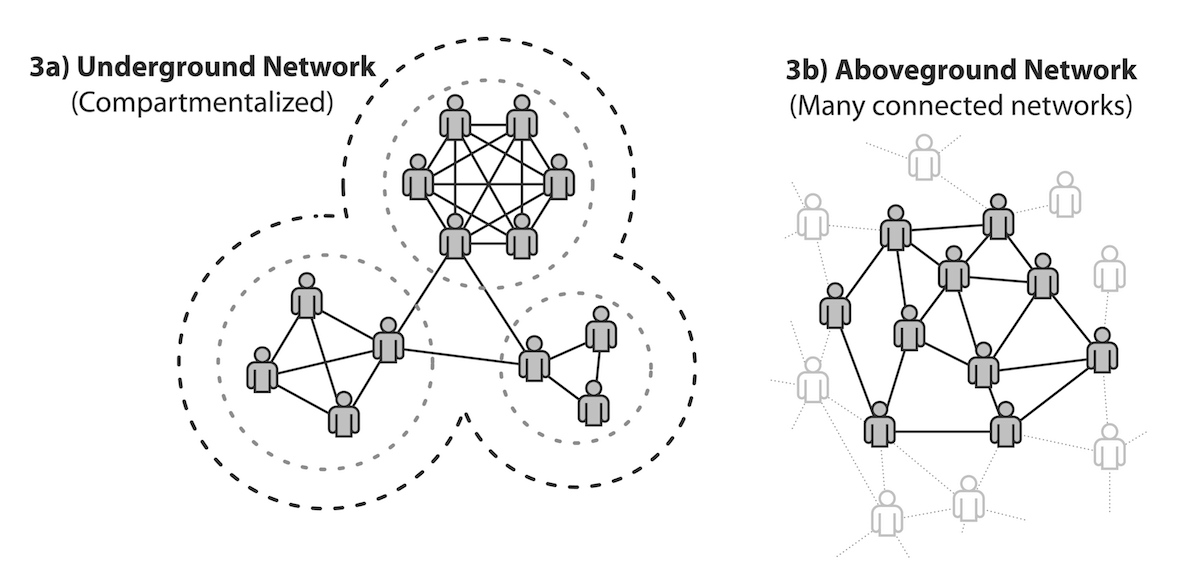

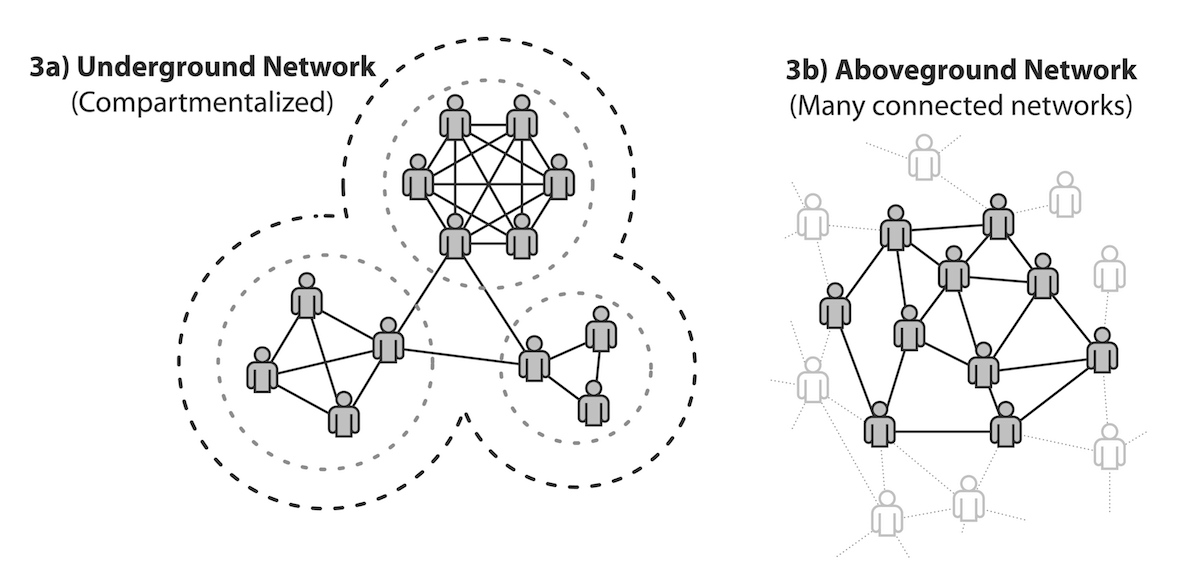

Here at Deep Green Resistance, we are an “aboveground” organization with a firewall between us and underground action. That means that our primary work is legal (although this varies depending on national laws). Our members also take part in non-violent direct action of the sort common among aboveground movements.

This is in contrast with “underground” organizations that conduct clandestine, highly illegal activities. We advocate for this, as we think coordinated underground action is the best chance for saving the planet.

We do not plan or carry out underground actions. We do not even know about these activities, except when public communiques (see our underground action calendar for examples) are made. Our role is to be the public organization advocating for and explaining these actions.

The Firewall

We call this separation the firewall between aboveground and underground activities. Maintaining a firewall is essential for security and effectiveness.

Assata Shakur was a member of the Black Panther Party (an aboveground organization) and the Black Liberation Army (an underground organization). She was active in the early 1970s and was eventually arrested. She escaped prison in 1979 and went on the run, eventually reaching Cuba. In 1987 she published the excellent book Assata: An Autobiography, which contains the following quote on the importance of a firewall.

“One of the [Black Panther] party’s major weaknesses was the failure to clearly differentiate between aboveground political struggle and underground, clandestine military struggle. An aboveground political organization can’t wage guerilla war anymore than an underground army can do aboveground political work. Although the two must work together, the must have completely different structures.”

More information on the importance of a firewall and security culture can be found in the Deep Green Resistance book, available here. We will end with a quote from the DGR book.

There has to be a partition, a firewall, between aboveground and underground activities. Some historical aboveground groups have tried to sit on the fence and carry out illegal activities without full separation. Such groups worked in places or times with far less pervasive surveillance than any modern society. Their attempts to combine aboveground and underground characteristics sometimes resulted in their destruction, and severe consequences for their members.

In order to be as safe and effective as possible, every person in a resistance movement must decide for her- or himself whether to be aboveground or underground. It is essential that this decision be made; to attempt to straddle the line is unsafe for everyone.

by DGR News Service | Jul 15, 2019 | Defensive Violence, The Solution: Resistance

Editor’s Note: this piece on the Art of Rebellion was published anonymously under the name “Seaweed” in 2008. We don’t agree with every detail (most notably, although we support autonomous localized uprisings, we don’t believe that these will be sufficient to halt the murder of the planet. We call for a more coordinated form of militant resistance to destroy industrial capitalism and save the planet). But this essay provides an excellent overview of the importance of martial traditions and developing a culture of militancy.

Image: Asia Ramazan Antar, a member of the YPJ, the all-female military force in northern Syria. Antar was killed by an ISIS suicide bomber in 2016, at the age of 19 years. YPJ is leading the fight against ISIS and Turkey as part of an ecological, feminist revolution in the heart of the Middle East. She is considered a hero of the Rojava revolution. Photo by Kurdishstruggle, CC BY 2.0.

By Seaweed

Even those of us in apparently open and peaceful countries are deeply involved in a war. It is a social and a political war. It is a war of ideology versus freedom of thought. It is a war of industrialism against healthy environments. It is a war between the included and the excluded.

The vast majority of the world’s population consists of defeated peoples in this war. And in fact, we are more than just defeated. We are kept. Kept in fear, kept in awe, kept out of touch with each other and the earth that gives us life. It has been said that our chains are long and our cages big, yet this still implies that we are prisoners. Coercion is everywhere, including the necessity to sell our labor for a wage, forced obedience to laws, conscription in imperial armies and compulsory moralities and schooling.

The occupying physical forces are essentially the police and the army. Over the centuries we’ve internalized much of the values and ideas of the conquerors. Most of us have now been assimilated into the ways of the obedient and the domesticated. But I’d like to explore our physical occupation, not the various skins that we must shed and the fears we must lose. If people want to claim space then they have to be prepared to fight and defend it. This space could be permanent (a liberated region or village) or temporary (squats, wilderness camps, legally and illegally built shelters or autonomous neighborhoods). It could be based in village or regional secessionist movements, access to land by popular movements or indigenous assertion over traditional territories.

Those of you familiar with the events in Kahnesatake for instance, a Mohawk reserve outside of Montreal, in which the cops were physically chased out of town a while ago, are aware of how successful an organized martial action can be. Canadian anarchists and other insubordinates have an incredible amount of insight and inspiration to glean from that event. People can claim space if they get organized and aren’t afraid to lose a few teeth.

With this in mind, perhaps a look at history generally will help us discover how others in this predicament have successfully organized themselves martially, because there are countless examples of rebels organizing themselves along martial lines and winning.

Official history is written by the conquerors. Their self-congratulatory folklore is that we (rebels) have always lost because the conquerors were superior (and thus had superior weapons). Most of us assume that this is true, so we might as well not even try a martial approach, because we’re sure to lose. But this isn’t the case. In North American history for instance, the dishonest image of the technologically advanced Europeans overrunning primitive savages needs to be re-examined. All over this continent the indigenous peoples rose up and used martial skills to repel the invasions. In most instances, at least initially, they had some success.

Let’s look at an example from one of the very first invasions. In 1521, in what is now called Florida, the Calusa and Timucua defeated experienced conquistadors under Ponce de Leon and Hernandez de Cordoba. In fact, both of these conquerors died of wounds inflicted by the Calusa! For half a century the indigenous tribes repelled the Spanish in that region. The invasion by de Leon and de Cordoba was in fact the fourth invasion by Spaniards repelled successfully by local tribes-people.

Throughout the successive invasions, there were countless examples of success. Furthermore, Europeans would not have ultimately won without adopting some native technology and skills while throughout the centuries the indigenous peoples also adapted European technology and tactics. For instance, in his excellent book, Warpaths, author Ian Steele explains that: “Spanish crossbows had failed to compete with Amerindian longbows that were six to seven feet long, thick as a man’s arm, and very accurate at two hundred yards. Although Spanish armor had been effective against most arrows encountered on three continents, these… arrows penetrated six inches of wood and even Spanish breast-and back plates.” In many instances the indigenous successfully defended their territory for decades, some even succeeded for generations.

It seems clear to me at least that any successful resistance needs to be organized in a broad way, it needs to be organically self-organized based on entire communities. We should be aiming for a period of regional and village-like secessionist movements. Centralized authority can not control a veritable multitude of rebellious regions, villages, reserves and neighborhoods, each with its own focus, its specific expression of anti-authoritarian self-organization. Also, by collaborating with or at least acknowledging indigenous actions for autonomy and territory, we can be part of something much larger, something quite close generally to what many insurgent communitarians, radical ecologists, anarchists and other rebels are aiming for.

As mentioned earlier, we still have to shake off the chains that we ourselves willingly carry, like crucifixes, because we are believers. Part of breaking out involves shedding all those ideological skins grafted onto us through schooling, the mass media, living in nuclear families, etc. But my involvement with rebels over the past 20 years tells me that we already know that this is important. What we don’t seem to inventory is the means available to us to counter our physical occupation. We know that it is only by ridding ourselves of organized coercive authority that we will truly begin to have real opportunities to profoundly transform ourselves. Can a local area succeed against this coercion and against the imperialism of the market? If so, what are some of the first steps?

Part of being an insurgent today could involve acquiring martial skills. Martial traditions include everything from fighting techniques, military theory, group cohesion and earth knowledge to skill with a weapon. Weapons include rifles, shotguns, handguns, sling shots, knives and various bows and arrows, among others. These could be used for acquiring food as well as for self-defense or to chase away adversaries. This isn’t a call to “armed struggle” but for inclusion of a neglected aspect of a holistic approach to rebellion. Most simple weapons are also useful tools and we should make use of them in that context, for instance by learning hunting skills, then bringing home some wild meat to share with friends so we can stop relying on dumpsters and food banks and jobs. The bonus is that our possession and familiarity with them could be extremely useful in a crisis situation or during a popular revolt.

The war rages on. The prisons are full. The factories and mines are full. A small class of people calls all the shots. A wave of extinction is denuding the planet, a tsunami caused by a system that is imposed from above. Entire populations are on anti-depressant and anti-anxiety pills. We need to regroup and strategize. Encouraging individuals and groups of rebellious people to get some training in survival and martial skills seems like common sense at this time. These various individuals and groups would help create a new anti-authoritarian culture that includes a widespread acceptance of a martial component. Rhetoric and politeness have ruled us for too long. A more martial approach should be given an opportunity to contribute significantly to attempts at creating imaginative, healthy cultures.

The support for martial skills could translate into anti-authoritarian “warrior societies” or “militias”, semi-formal groupings that exist over time, or it might manifest itself spontaneously and informally when the need arises. Either way, the intention is that there are groups of individuals able and perhaps willing to help their neighbors, comrades and friends claim space to express anger, resist the plundering of their habitat and help various grassroots initiatives to fight back through the practice of martial approaches. They would likely practice survival and martial skills. When a squat is about to be evicted or a wilderness camp burned by authorities, they might show up to give moral and physical support with their training and ability to act strongly as a group. Whether groups form or not, by being inclusive and encouraging as many friends, neighbors and comrades as possible to explore martial ways, an exciting new culture will be given the opportunity to emerge.

Canadian rebels can take advantage of the relative freedom and openness of our society and get these skills and tools before the chains shorten and the cages shrink. The reaction to the September 11th events in the USA proved just how quickly an open society will bring in draconian laws to protect the elite, the system they depend on and the values that allow such a system to exist in the first place.

We are all occupied peoples. The occupation is partly maintained militarily and our response should therefore be, in part at least, a military one. But I don’t want a warrior ethic to be the central aspect of my community. I want the wisdom of the elders, the spontaneity, playfulness and brutal honesty of the children, the careful chiding and questioning of the fools and pacifists to also be essential aspects of my resistance, otherwise we’ll end up with martial societies rather than societies with martial skills, or worse, warrior aristocracies. I’m not suggesting a separate warrior class, but an anti-authoritarian culture that values martial skills and tactics. Community wide training in self-defense, widespread use and knowledge of weaponry, popular study of conflict and confrontation, general encouragement of fighting back and standing up, etc. would all be central. I’m encouraging a grassroots acceptance of martial skills and approaches.

The warriors we want to encourage are partly motivated by a concern and caring for others in their community. They aren’t based in small sanctimonious cliques. However, they care about others because they care about themselves, about life generally, about freedom. Our fighter exists to claim space for herself and others. In this newly freed up space genuine living can have an opportunity to express itself.

Part of preparing ourselves for secession and revolt includes the study of military history, the principles and ways of warfare, mostly because our adversaries are well schooled in it, but also because these offer insights and principles valuable to anti-authoritarian rebels as well. Many of us are familiar with some of the classics: Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Musashi’s Book of Five Rings, Che Gueverra’s writings, Mao’s musings and analysis and the works of Clausewitz for instance. But these are only some of the works, many from an authoritarian or vanguardist perspective, and clearly inadequate for an emerging martial culture wanting to resist or to claim and defend space.

We could also look at the history of anarchists, like the Makhnovchina or the Durruti Column, for instance, at how they got started, how they were organized as well as at some of their specific battles and how these were won or lost. We can learn from the mistakes of countless past attempts. Anti-authoritarian rebels don’t have an elitist leadership and aren’t centrally organized. Federations of independent camps could be encouraged, but these alliances should be fragile agreements. Ultimately it is in not becoming too formally linked that we will succeed in permanently breaking the existence of political monopolies and large-scale infrastructures that tend toward congealing into authoritarian organizations. The notion here is to be a small part in helping create a world of free individuals, of healthy ecological environments where self-organized groups of free humans can live.

This new focus of rebellious people on military history and strategy would obviously be well complimented by also including the struggles of indigenous and other insurgent groups. In this respect we could also look at the Metis rebellion around the Red River Valley and the Society of the Masterless Men in Newfoundland, for instance. Of course we’d benefit as well from a study of the battles of war leaders like Crazy Horse, Tecumseh, Chief Joseph, Pontiac and Geronimo, as well as events like John Brown’s attempted seizure of the armory at Harper’s Ferry and countless other examples.

A study of the military attempts of anti-authoritarian and indigenous rebels that focuses on specific battles and the strategies that either won or lost them the fight, can lead to many useful insights of the art of revolt. A look at the struggle of the Potawatomi for instance, a people who lived according to open and free principles, to survive while caught up in the conflicts between the French and English colonial powers, reveals secrets of successful warfare. Here is just one example. In the spring of 1755, Major General Braddock assembled a large army under the British flag. He was leading colonial militia and regular troops from Virginia to destroy French forts on the Ohio River. His guide and adviser was a young colonel, George Washington. Here’s a description of what transpired from James Clifton’s book The Potawatomi:

“On June 8 the British were approaching Fort Duquesne in western Pennsylvania, site of present day Pittsburgh. Seeing that the British were camped and on the alert, the Potawatomi war leaders persuaded the French not to attack. Instead, they planned to attack the British troops the next day while they were on the move, stretched out in mile-long files along a narrow, forest-shrouded trail. Their surprise attack was a complete success. Colonel Washington tried to…counterattack in Indian style…but was defeated. They suffered nearly 1000 dead and wounded out of 1500 on the trail that morning. They abandoned most of their equipment and supplies… Braddock was mortally wounded. Washington barely escaped with his life. He learned a life-saving military lesson from this disaster, one that he would regularly give as advice to his own generals when sending them against British and Indian forces: “Beware of surprise!”

In military theory, surprise is one of the most potent weapons available. We should keep in mind that a study of historical combat shows that surprise increases the combat power of fighting forces. It is the greatest of all combat multipliers. Surprise, combat effectiveness, defensive postures, these are all multipliers that can help. Shouldn’t this knowledge be generally available and understood among anti-authoritarians?

The following are just a few examples of using martial tactics to succeed in present day struggles.

Opening new fronts as solidarity with other rebels engaged in a confrontation or action. Encouraging defection within enemy ranks. Avoiding capture. Blockades. Unarresting a comrade. The ambush. Spying. Interrupting the enemies’ means of communication. The surprise. Raids on enemy stores of food and weapons. The siege. Physical battles that expand territory. Freeing captives from enemy prisons. Destruction of enemy arsenals. Destruction of enemy wealth. Regrouping. Hiding. Secret codes and other means of communication. Bolder actions. Creating clandestine camps in which to hide friendly fugitives. Insurgencies. Fleeing to areas outside the enemies’ control. Increased ability to fight as groups.

Like all strategies involving territory and occupation, the defeated have myriad choices in terms of how they live out their lives. But the choices are more limited if we agree on what our aims are, on what would constitute success, on what constitutes living. Were the Warsaw Ghetto inhabitants who rose up against their Nazi tormentors ethically reprehensible for killing? Should they have continued to accept daily humiliation, suffering, violence and death? Yet at the time, there were those among them who argued against the uprising on various grounds, including moral ones. Oftentimes it isn’t a question of who was more successful, but agreeing on what success is. In the case of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, those who participated in the uprising felt it was more successful to stand up to their oppressors and die with dignity, than to continue to live in Nazi hell. For others success was measured simply by staying alive at all costs, even if that meant being a traitor or accepting defeat. For others still, success was measured by being morally superior, by never adopting the means and ways of the enemy, even if that meant suffering or death. All rebels who want to overthrow the present social order in favor of a more just and imaginative one, need to ask themselves what success means for them. I believe it means standing up to the bullies who run things. It means asserting some territoriality within which we can learn to live in harmony with each other and the world around us. To achieve this we need to listen to the hot headed, impatient and courageous warriors as much as we do to the cautious, negotiating and compromising survivors.

We are all damaged people who need to heal and not just fight. We partly do this with others with whom we share affinities and openness for intimacy. We also need to analyze civilization (or domination generally) and share our insights through debates, pamphlets, publications and discussion. And we need to help create communities and/or cultures of resistance by contributing to the various projects that fellow rebels are involved in. Yet personal healing, propaganda and putting our energy into community projects, no matter how worthy, still don’t acknowledge the military occupation we are presently living under. Even attempts at “re-wilding” are vain if we don’t push for a generalized, effective, long-term momentum against militarily protected centralized authority.

History is not only the story of imperial civilizations targeting and conquering others, it is also a chronicle of the resistance to that conquest. I have allies and kin that extend back millennia. They have won countless battles. There has been successful resistance in every area and every era. In order to honor our ancestors, and I use this term broadly in the sense of ancestors by blood or worldview, we need to give them thanks and keep up the fight. In military theory, it is said that for the conqueror to really succeed the losing population must accept defeat, otherwise the conquerors only win after every single person has been killed, which isn’t normally in the conquerors interest, because they need slaves and soldiers, etc. A very large part of our population unfortunately has accepted defeat. So I want to repeat that sharing our unique world-views and critiques and creating community are as essential as acquiring martial skills. A martial component is simply one part of a holistic approach. But we also must remember that a small band of rebels can accomplish a lot, even succeeding in leading relatively free lives away from capitalist civilization.

In Ireland, in the early nineteen hundreds, small local militias with not even enough rifles to go around succeeded in thwarting the designs of one of the most powerful empires on the planet for decades. They were successful partly because they used many martial skills, from spying to engagement in actual battles but also because they had widespread support. The fighters could melt back into the population. Disadvantaged fighters need widespread support to win. With this in mind, it’s essential that rebels stay put in one region and make strong bonds with the land and the inhabitants there. Perhaps, over time, the embers of authentic communities with martial skills will begin to glow and maybe these seemingly isolated embers will one day gather themselves into small local fires. And hopefully, you’ll be a rebel around one of those fires.

PDF for printing available here: https://ia801308.us.archive.org/19/items/OfMartialTraditionsTheArtOfRebellion/martial_traditions-imposed.pdf

by DGR News Service | Jul 4, 2019 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Repression at Home

Communiqué from the Popular Indigenous Council of Guerrero-Emiliano Zapata (CIPOG-EZ) on the recent murder of its members, Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote.

May 2019, Lower Mountains of the State of Guerrero.

To the Zapatista Army of National Liberation

To the National Indigenous Congress

To the Indigenous Governing Council

To the People of Guerrero

To the Peoples of Mexico and the World

To the National and International Sixth

To the Networks of Resistance and Rebellion

To the CIG Support Networks

Twenty days after the cowardly murder of our brothers, Lucio Bartolo Faustino and Modesto Verales Sebastián, impunity continues at the three levels of government. We the Nahua people of the mountains of the state of Guerrero are grieving and angry. We publicly denounce the hideous murder of our brothers, Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote, who were both Indigenous Nahuas and local promoters of the Popular Indigenous Council of Guerrero – Emiliano Zapata (CIPOG-EZ). The people who carried out this atrocious assassination are professional paramilitaries. They were not satisfied to just to take their lives away; they denigrated them, showing no mercy in this extrajudicial assassination. They dismembered them and put our compañeros in bags. They thought through this vile act they would also demean their story and denigrate their lives. They are wrong.

Not only are they wrong, but the dignity of their lives stands in contrast to the cowardice acts of the murderers. The peoples of CIPOG-EZ and CNI of Guerrero, Mexico are keeping alive the memory of the men and women who have lost their lives in the struggle for the reconstitution of collective rights. We therefore ask the dignified people of Mexico and of the world to remember and spread the word about the history of our murdered brothers and their struggle to defend life; Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote. Lucio Bartolo Faustino and Modesto Verales Sebastián.

We hold the three levels of government categorically responsible: the federal government headed by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the state government of Héctor Astudillo Flores and the municipal government of Jesús Parra García. Each level of government has held no one accountable, passing the ball to each other saying that the problems were inherited from past governments. This is the PRI attitude that has immersed our country into a bloodbath. There is no “transformation” that wants to change things and it seems that the only important changes occur in the upper spheres of government. The people in power don’t care about the lives of the people below.

The different narco-paramilitary groups have operated for more than twenty-five years in the region of Chilapa, in complicity with the Mexican State, and today is no exception. The state regime has tried over and over to divide our people and we have resisted the war of extermination for more than five hundred years. Our crime has been to defend our territory from the extraction of what they call “natural resources” which for us are sacred mountains or water springs and life. We struggle to maintain the principles that we inherited from our grandparents, which we call “uses and customs”. This world is very different than the one that the Mexican State has formed which goes against our form of community government.

Our towns are suffering systemic violence in which our women, children and men go missing or are murdered, and nothing seems to happen. Everything remains in complete impunity for this bad government, where one of the strategies of the state is to create terror in the heart of our people. Using torture, psychological warfare, death threats, and persecution against all members who promote community development.

We as Indigenous peoples ask ourselves over and over: Why is there so much dehumanization? Why is human life not worth more? Why are some lives worth less than others? And it seems that those on top see us at the bottom as commodities. We ask ourselves again and again, how would the powerful, the governments with more than 30 million votes, react if this violence were to happen to one of their relatives? Or if they were missing, were tortured and viciously murdered or are those acts only reserved for us?

As a national Indigenous movement we fight to reconstruct the social fabric of our people. We are fighting to re-establish peace in our communities, and seek to recognize and reconstruct our indigenous languages, culture and the thinking of our peoples that is interwoven with mother earth.

On May 23, 2019 around 1:30 pm, our brothers Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote went missing near Chilapa de Álvarez, Guerrero. On the morning of May 24 we learned the terrible news; their lifeless bodies were found. Today we are making a public denunciation and asking for honest and dignified comrades from Mexico and the world; no matter how much they want to destroy us, today let us embrace the history of struggle, which is the history of struggle of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico and the world.

We demand justice for our murdered brothers: Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote. Lucio Bartolo Faustino and Modesto Verales Sebastián. May the pain that overwhelms us today as relatives, friends and compañeros in struggle, not remain in impunity, nor be forgotten.

FRATERNALLY:

Justice for Bartolo Hilario Morales and Isaías Xanteco Ahuejote, CNI members!

Justice for Lucio Bartolo Faustino and Modesto Verales Sebastián, CIPOG-EZ member and former member of the CIG and CNI!

Justice for Gustavo Cruz Mendoza, Indigenous communicator assassinated from the CIPO-RFM!

Justice for Samir Flores Soberanes, Indigenous communicator assassinated!

Stop the counterinsurgency war against the EZLN!

Freedom for Fidencio Aldama of the Yaqui tribe!

Never again a Mexico without us!

Popular Indigenous Council of Guerrero-Emiliano Zapata (CIPOG-EZ)

Regions Costa Chica, Costa Montaña, Montaña Alta and Montaña Baja de Guerrero