by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 7, 2015 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Indigenous Autonomy, Indirect Action

In early October, news emerged that India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change was blocking the implementation of a high-level government panel’s report on tribal rights that recommended the creation of stringent rules to safeguard indigenous people from displacement. Meanwhile, two state governments have begun implementing a much different set of guidelines — issued in August without any interference — that allow the private sector to manage 40 percent of forests for profit at the expense of indigenous forest dwellers. In addition, another ordinance passed this year will permit private corporations to easily acquire land and forests from indigenous communities and carry out ecologically harmful mining. These legislative and policy decisions are usually made without the knowledge of indigenous communities whose lives, livelihoods and ecosystems will be worsened by these irresponsible actions of the government. Hence, indigenous communities in Uttar Pradesh, a northern state and Odisha, in the east, are strengthening their organizing to protect their rivers, lands, forests and hills from “development” that would displace thousands of local residents and destroy the environment.“People from my community and I were beaten, detained or jailed unnecessarily for opposing tree felling in our forests, some years ago,” said Nivada Debi, a feisty 38-year-old woman from the Tharu Adivasi community in Uttar Pradesh. “We visited the police station multiple times for their release. The government did not assist the injured. Despite the police and government indifference, we will fight for our land and environment.”A mother of four children subsisting on the forests, Debi is active in grassroots resistance that started nearly 20 years ago and has grown into the All India Union of Forest Working People, or AIUFWP. The group is made up of many indigenous people who subsist on forests and are collectively protecting forests from poachers and encroachers.

Debi was among hundreds — from the AIUFWP, the allied Save Kanhar Movement and other resistance groups — who traveled to Lucknow in July 2015 for a rally protesting the continued incarceration of their comrades fighting land grabbing in other districts of Uttar Pradesh. Roma Malik, the AIUFWP deputy general secretary, and Sukalo Gond, an Adivasi, which means original inhabitant, were among those arrested on June 30, before they were to address a large public gathering about the illegal land acquisition for the Kanhar dam and the violent repression of its opponents by the state. Another member of AIUFWP, Rajkumari, who prefers to go by her first name, was jailed on April 21, after 39 Adivasis and Dalits, who are considered outside the caste hierarchy, were brutally shot at by the police during a peaceful protest on April 18. The demonstration, which began on April 14 — the birthday of B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian constitution and an icon for many Indians, particularly Dalits — was opposing the construction of a dam across the Kanhar river in the Sonbhadra district of southeastern Uttar Pradesh.

Rajkumari was released toward the end of July while Gond and Malik were freed in September. However, others are still imprisoned on fabricated charges. Courts are delaying hearing their cases or denying them bail.

AIUFWP members, some of whom were previously involved with other local resistance movements, have been actively opposing the construction of the Kanhar dam for years. It would submerge over 10,000 acres of land from more than 110 villages in Uttar Pradesh and the neighboring states of Chattisgarh and Jharkhand, displacing thousands of local people and disrupting their lives and livelihoods. The dam was approved by the Central Water Commission of India in 1976, but was abandoned in 1989 after facing fierce opposition, especially from the local people whose lives and ecosystem would be destroyed by the proposed dam. However, construction resumed in December 2014, violating orders to stop it from the National Green Tribunal — a government body that adjudicates on environmental protection, forest conservation and natural resource disputes. No social impact assessment was done, nor were the necessary environmental or forest clearances — mandated by the Forest Conservation Act — obtained by the state government.

“Since this dam can destroy our survival and also adversely impact the surroundings, we have been opposing its construction and related land acquisition for many years,” said Shobha, a determined 42-year-old Dalit. “On December 23, 2014, the police caned some of our comrades when we were peacefully protesting the revival of building the dam earlier that month. However, the police falsely accused some leaders of our struggle of attacking the sub-divisional magistrate.” Shobha, who also prefers to go only by her first name, is among the vocal leaders of a women’s agricultural laborers union, which has allied with AIUFWP, in the village of Bada.

Around 400 miles from Sonbhadra, in the Kalahandi and Rayagada districts of southern Odisha, live the Dongria Kondhs, an indigenous community of over 8,000 people. They have been fighting tirelessly to protect their sacred mountain, the nearly 5,000-foot high Niyamgiri, from large private corporations — like Vedanta Limited — that are trying to mine bauxite in the area to produce aluminum. Supporters of the Dongria Kondhs were arrested in Delhi on August 9 outside the Reserve Bank of India, as they peacefully highlighted Vedanta’s illegitimate and harmful mining in the Niyamgiri. Vedanta’s mining would violate the Forest Rights Act, which states that indigenous communities are entitled to remain in the forests — and utilize the produce, land and water in the forests — while conserving and protecting them.

“The Niyamgiri symbolizes a parent to our community,” said Sadai Huika, a steadfast 45-year-old Dongria Kondh woman from Tikoripada village. “While the streams that originate from it help our farming, the plants and grass that grows on it feed our cattle and goats. We cannot exist without it and will safeguard it from anyone trying to harm it.”

Huika and people from hundreds of villages near the Niyamgiri are active members of the Niyamgiri Protection Forum, which originated around 2003 to resist attempts by Vedanta to begin mining where the Kondhs live, with the support of the Odisha state government. At every one of the 12 village council meetings with government officers held in 2013 atop the Niyamgari, community members stated that they would not allow mining nearby.

Kumuti Majhi, an elderly Dongria Kondh man and one of the forum’s leaders, is among the few people who have traveled within and outside Odisha to advocate against mining and garner vital support for their struggle. He has met ministers to explain how significant the Niyamgiri is to his community and their reasons for safeguarding it.

By organizing protests locally and with allies around the world — and meetings with Vedanta’s shareholders and empathetic government officials, who the forum has enlightened about the need to protect the Niyamgiri — the group has stalled the mining.

“We know that extracting bauxite from the Niyamgiri will pollute our environment and also affect all living beings here,” Majhi said. “Hence, we will stop anyone coming to plunder the Niyamgiri, despite police harassment and false charges against us and our families.”

Pushpa Achanta is a Bangalore-based freelance journalist, blogger and writer on development and human interest issues. She is the lead author of a book titled Ripples: The Right to Water and Sanitation for Whom, published in July 2013 by the Indian Social Institute in Bangalore. Her articles have appeared in collections of essays and features on different subjects. She also enjoys penning verse, taking nature photography and mentoring youth.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Nov 3, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Repression at Home

By Cultural Survival

Two Q’anjobal Maya community leaders who were imprisoned in Guatemala for the past two years, have finally been declared innocent and released. A regional Guatemalan criminal court found the two men to be absolved of all charges on October 28, 2015.

Rogelio Velasquez and Saul Mendez had been unfairly imprisoned as a result of their activism organizing against a Spanish hydroelectric dam project in their town of Santa Cruz Barillas, Huehuetenango. The two men have had a long trajectory as community leaders, participating in the organization and promotion of a community consultation in 2007 and again in 2011, in which members of the Indigenous Q’anjobal Maya community voted overwhelmingly to reject any outside companies from conducting resource exploration or extraction. The Spanish company has ignored these demonstrations; rather than respecting the autonomy of the community, have pushed violently and aggressively forward with their plans for a dam on the sacred Qam Balam river. Velasquez’ and Mendez’ villages were the first to rise up against the dam, as they were the most likely to be affected by the project.

This is the second stint that the men have done in prison. In May 2012, they were arbitrarily detained in Barillas after protesting outside of military headquarters after the assassination of their neighbor and fellow community leader Andres Francisco Miguel. Along with along with seven other men, they were illegally held in prison for 8 months, until finally being released in January 2013 after no charges were brought against them. In November 2012, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention emitted a statement 46/2012 confirming that these arrests were arbitrary.

Then, eight months later, two men dressed as police officers- but lacking any police identification- detained Velasquez and Mendez and put them back in prison. Later charges were filed accusing the men of having “participated’’ in a public lynching that occurred three years earlier in 2010. Mendez and Velasquez have maintained their innocence.

In an interview the day before their trial on the 28th, Prensa Comunitaria reported that after two years, 2 months and one day in prison, the men remained as lively as ever. “We kept a promise to the town of Barillas and its people. We are in prison for defending what belongs to the community and that’s why we know that the people will support us,’’ they said. The men have lived in constant worry about their wives and children, the harvesting of their corn fields, and whether their families have had food to put on the table. They were forced to learn how to find hope even at the darkest of moments; Rogelio Velasquez has dedicated his time to learning to read and write. Saul Mendez has been weaving, creating sachels and bracelets decorated with the word “Libertad’’.

Arbitrary detention and the criminalization of human rights defenders has become a rampant epidemic in Guatemala, especially against Indigenous leaders.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner summary of stakeholder submissions to the Human Rights Council Working Group, during the Universal Periodic Review of Guatemala in 2012 noted,

“HRDs [Human Rights Defenders] continue to face death threats, physical attacks, killings and other forms of violence, mostly carried out by clandestine security organizations and illegal groups… The illegitimate use of criminal proceedings against HRDs prevented them from carrying out their legitimate activities… The worsening situation of human rights defenders was directly related to the failure to address land conflicts and the repressive policy pursued against indigenous communities who object to the use of their natural resources without prior consultation.”

The threats to the safety of Indigenous human rights defenders are growing, and it is left to be seen how Guatemala’s new president-elect Jimmy Morales’ administration will affect change. But for now, at least two more men have been able to return home to their families.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Mar 8, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. Due to the length of the interview, we’ve presented it in three installments; go to Part II here, and Part III here.

Time is Short: Can you give a brief description of what it was you did?

Michael Carter: The significant actions were tree spiking—where nails are driven into trees and the timber company warned against cutting them—and sabotaging of road building machinery. We cut down plenty of billboards too, and this got most of the media attention. We did this for about two years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about twenty actions. My brother Sean was also indicted. The FBI tried to round up a larger conspiracy, but that didn’t stick.

TS: How did you approach those actions? What was the context?

MC: We didn’t know a lot about environmental issues or political resistance, so we didn’t have much understanding of context. We had an instinctive dislike of clear cuts, and we had the book The Monkey Wrench Gang. Other people were monkeywrenching, that is, sabotaging industry to protect wilderness, so we had some vague ideas about tactics but no manual, no concrete theory. We knew what Earth First! was, although we weren’t members. It was a conspiracy only in the remotest sense. We had little strategy and the actions were impetuous. If we’d been robbing banks instead, we’d have been shot in the act.

Nor did we really understand how bad the problem was. We thought that deforestation was damaging to the land, but we didn’t get the depth of its implications and we didn’t link it to other atrocities. We just thought that we were on the extreme edge of the marginal issue of forestry. This was before many were talking about global warming or ocean acidification or mass extinction. It all seemed much less severe than now, and of course it was. The losses since then, of species and habitat and pollution, are terrible. No monkeywrenching I know of did anything significant to stop that. It was scattered, aimed at minor targets, and had no aboveground political movement behind it.

Clearcuts in the Swan Valley, MT near Loon Lake on the slope of Mission Mountains. Photo by George Wuerthner.

TS: What was the public response to your actions?

MC: They saw them as vandalism, mindlessly criminal, even if they were politically motivated. This was before 9/11, before the Oklahoma City bombing; the idea of terrorism wasn’t so powerful, so our actions weren’t taken nearly as seriously as they would be now.

We were charged by the state of Montana with criminal mischief and criminal endangerment. The state’s evidence was solid enough we thought we couldn’t win a trial, so we pled guilty on the chance the judge wouldn’t send us to prison. Our defense was to say, “We’re sorry we did it, it was motivated by sincerity but it was dumb.” And that was true. We were able to get our charges reduced from criminal endangerment to criminal mischief. I got a 19 year suspended prison sentence, Sean got 9 years suspended. We both had to pay a lot of money, some $40,000, but I only spent three months in county jail and Sean got out of a jail sentence altogether. We were lucky.

TS: As you said, this was before the obsessive fear of terrorism. How do you think that played into your trial and indictment, and how do you think it would be different today?

MC: Had it happened after any big terrorism event, they would have sent us to prison, there’s no doubt about that. States have to maintain a level of constant fear and prove themselves able to protect citizens.

The irony was, I’m not sure I wanted to be serious—there seemed to be something protective in not being all that effective, in being intentionally quixotic, in being a little cute about it. There was a particularly comical aspect to cutting down billboards, and that was helpful only when I was arrested. It made it look less like terrorism and more like reckless things I did when I was drunk, and a lot of people approved of it because they thought billboards were tacky. I want to emphasize that cutting down billboards is nothing I’d advise anyone to consider, only that a little bit of public approval made a surprising difference to my morale, and may have positively influenced sentencing. But the point, of course, is to be effective and not get caught in the first place. These days, if someone gets caught in underground actions, they will be in a lot more trouble than ever before.

TS: How did you get caught?

We left fingerprints and tire tracks, we rented equipment under our own names—like an acetylene torch used to cut down steel billboard posts—and we told people who didn’t need to know about it. We assumed we were safe if they didn’t catch us in the act and because our fingerprints weren’t on file, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. The cops can subpoena anyone’s fingerprints, and use that evidence for something in the past. The importance of security can’t be overstated—and we didn’t have any. Even with a couple rudimentary precautions, we might have saved ourselves the whole ordeal of getting caught. If we’d read the security chapter of Dave Foreman’s book Ecodefense, I don’t think we would have even come under suspicion. Anyone taking any action, above- or underground, needs to take the time to learn security well.

It’s not just saving yourself the anguish of arrest and prison time. If you’re rigorous about security, you might be able to have a real chance at changing how the future of the planet plays out. You can have no impact at all in a jail cell. In our case, we definitely could have stopped timber sales with tree spiking even though that tactic was extremely unpopular politically. It was seen as an act of violence against innocent lumber mill workers instead of a preventative measure to protect forests. The dilemma never got past that stage, though. We had little chance of having any reasoned tactical considerations—let alone making reasoned decisions—because we were always a little too afraid of being caught. With good reason, it turns out.

TS: What have you learned from your experience? Looking back on what you did all those years ago, what’s your perspective on your actions now? Is there anything you would have done differently?

MC: Well I definitely would have taken steps to not get caught. I would have picked my targets more carefully, and I would have entered into an understanding with myself that while my enemy is composed of people, it’s only a system, inhuman and relentless. It can’t be reasoned with; it has no sanity, no sense of morality, no love of anything. Its job is to consume. I would have tried to focus on that guiding fact, and not on the people running it or who were dependent on it. I would have tried to find the weaknesses in the system, and then attacked those.

I’d have tried not to allow my emotions to dictate my strategy or actions. Emotions might get me there in the first place—I don’t think you could get to such a desperate point without a strong emotional response—but once I arrived at the decision to act, I would have done everything I could to think like a soldier, find a competent group to join with, and pick expensive and hard-to-replace targets.

TS: I assume you didn’t just wake up one day and decide to attack bulldozers and billboards. What was your path from being apolitical to having the determination and the passion to do what you did?

MC: When I was struggling with high school, my brother loaned me a stack of Edward Abbey books, which presented the idea that wilderness is the real world, precious above all else. The other part was living in northwest Montana, where you see deforestation anywhere you look. You can’t not notice it, and there’s something about those scalped hills and skid trails and roads that triggers a visceral, angry response. It’s less abstract than atmospheric carbon or drift-net fishing. You don’t see those things the way you see denuded mountainsides. My family heated the house with wood, and we would sometimes get it out of slash piles in the middle of clearcuts. I had lots of firsthand exposure to deforested land. I wondered why the Sierra Club didn’t do something about it, how it could be allowed. We would occasionally go to Canada, and it was even worse up there. No one can feel despair like a teenager, and I had it in spades. If Greenpeace won’t stop this, I reasoned, well then I will.

I started building an identity around this, though, and that’s disastrous for a person choosing underground resistance. You naturally want others to know and appreciate your feelings and accomplishments, especially when you’re young, but the dilemma underground fighters face is that they must present another, blander identity to the world. That’s hard to do.

TS: You were fairly isolated in your actions, and you’ve emphasized the importance of a larger context. Do you see those two ideas connecting? Do you think saboteurs should be acting in a larger movement?

MC: I think saving the planet relies completely on the coordinated actions of underground cells coupled with an aboveground political movement that isn’t directly involved in underground actions. When I was underground, I had no hope of building a network, mostly because of a lack of emotional and political maturity. I also didn’t have the technological or strategic savvy, or a means of communicating with others. The actions themselves were mostly symbolic, and symbolic actions are a huge waste of risk. They’re a waste of political capital too. Most everyone is going to disagree with underground activism and it’s not going to change anyone’s mind about the policy issue—hardly anything will—so it has to count in the material realm. If people are ready and willing to risk their lives and their freedom then they should fight to win, not just to make some sort of abstract point.

TS: After you were arrested, what support—if any—did you receive from folks on the outside, and what support would you have wanted to receive?

MC: The most important support was financial, but there wasn’t a lot of it. Our plea bargain didn’t guarantee we wouldn’t go to prison. We were also worried that the feds would indict us for racketeering, an anti-Mafia charge with serious minimum sentencing. If we’d had more legal defense financing we’d of course have felt a lot more secure, but twenty years of reflection tells me we didn’t really deserve it considering how poorly we executed the actions, what little effect they caused.

That sounds like I’m being awfully hard on myself, and hindsight is always 20/20, but the point is that a legal crisis is exhausting and expensive. Your community will question whether your actions are worthy of the price they’ll have to pay if you’re caught. My actions were not.

Even so, I appreciated any sort of support. Hearing from the outside in jail is better than you’d believe. A lot of Earth First! Journal readers sent me anonymous letters. I wrote back and forth with one of the women who was jailed for noncooperation with a federal grand jury investigating the Animal Liberation Front in Washington. Seeing approving letters to the editor in the papers was also great. Just knowing that the whole world isn’t your enemy, that someone is thinking about you and appreciates what you did, is priceless.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

TS: Do you still think militant and illegal forms of direct action and sabotage are justified? Why?

MC: I do, yes. In an ideal world I don’t think violence is the best way to accomplish anything, but obviously this isn’t an ideal world. Our circumstances are getting worse and worse—overpopulation, pollution, oceanic dead zones, you name it—and any options for a decent and dignified future for humanity are dwindling day by day, so what choice does that leave us? Individual attempts at sustainable living won’t work so long as the industrial system is running. The dismantling of infrastructure is the most important missing piece right now. It’s where the system is most vulnerable, so it should be employed right away. It can be effective, but it has to be responsible, careful, and extraordinarily smart.

One of the reasons underground political actions are so unpopular is that they’re always presented as attacks on individuals, rather than on a system. I think it’s important to reframe sabotage as strikes on an unjust, destructive system, and that civilization is not us, and not the highest expression of human endeavor, but only an idea. Civilization is masquerading as humanity, but that’s not what it is. Civilization is only one sort of cultural plan, a way of creating unsustainably large human settlements, based entirely on agriculture which itself is completely unsustainable.

The argument that militant actions are counterproductive has a little bit of merit because the scale they’ve happened on hasn’t been large enough to have any impact. For example, the Earth Liberation Front burning SUV’s. You’re left with the political fallout, the mainstream activists distancing themselves and all the other bad stuff that comes with it, but you don’t have any measurable gain, in reducing carbon emissions, say. Sabotage needs to happen on a larger scale, against more expensive targets, to be impactful. Fighters need to think big. That’s how militaries accomplish their goals—by acting against systems. They blow up bridges, they take out buildings, they disable the enemy arsenal, they kill the enemy—that’s how they function. I agree activists don’t want to identify with militarism, but it’s foolhardy to not consider what’s actually going to get the job done, and militaries know how to do that. No moral code will matter if the biosphere collapses. Doctrinal non-violence isn’t going to have any relevance in a world that’s 20 degrees hotter than it is now.

I wish an effective movement could be nonviolent, but we just don’t have enough social cohesion to orchestrate that kind of thing. There’s so few of us who give a shit, and we’re scattered, isolated, and disenfranchised. We don’t have adequate numbers, influence, or power, and I don’t see that changing. Everywhere we look we’re losing, because we don’t have a movement that can say, “No. You’re not going to do that. We will stop this, whatever it takes,” and back that up. Aboveground activists need to advocate a lesser evil, to continually pose the question of what is worse: that some property was destroyed, or that sea shells are dissolving in acid oceans? Underground activists need to act that out. It’s not a rhetorical question.

We need to remember, too, that small numbers of people can engineer profound changes when their actions are wisely leveraged. Very few took part in the resistance movements of World War II, but they made all the difference to ultimately defeating the Axis.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 7, 2014 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

By Jonathan Watts / The Guardian

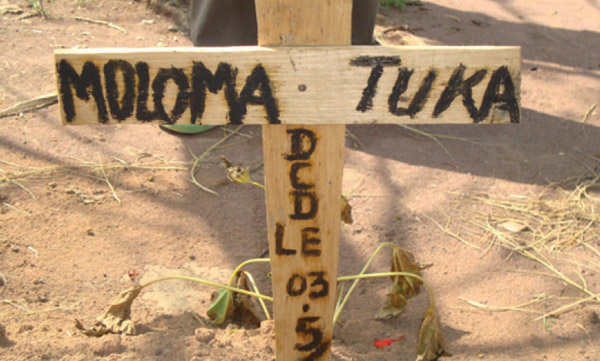

The body of an indigenous leader who was opposed to a major mining project in Ecuador has been found bound and buried, days before he planned to take his campaign to climate talks in Lima.

The killing highlights the violence and harassment facing environmental activists in Ecuador, following the confiscation earlier this week of a bus carrying climate campaigners who planned to denounce president Rafael Correa at the United Nations conference.

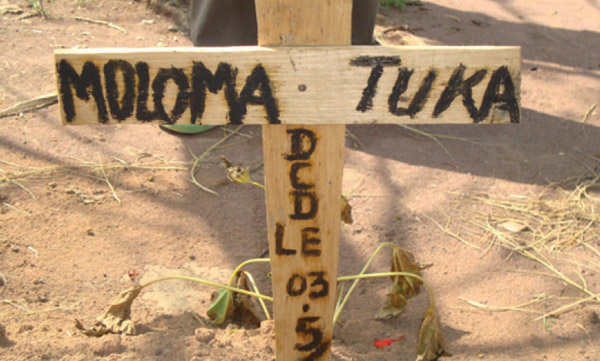

The victim, José Isidro Tendetza Antún, a former vice-president of the Shuar Federation of Zamora, had been missing since 28 November, when he was last seen on his way to a meeting of protesters against the Mirador copper and gold mine. After a tip-off on Tuesday, his son Jorge unearthed the body from a grave marked “no name”. The arms and legs were trussed by a blue rope.

Other members of the community said Tendetza had been offered bribes and had his crops burned in an attempt to remove him from the area.

Domingo Ankuash, a Shuar leader, said there were signs Tendetza had been tortured, but the full facts had yet to come to light. He said the family were extremely unhappy with the investigation and what they said was the reluctance of the authorities to conduct a timely autopsy.

“His body was beaten, bones were broken,” said Ankuash. “He had been tortured and he was thrown in the river. The mere fact that they buried him before telling us, the family, is suspicious.”

Tendetza had been a prominent critic of Mirador, an open-cast pit that has been approved in an area of important biodiversity that is also home to the Shuar, Ecuador’s second-biggest indigenous group.

The project is operated by Ecuacorriente – originally a Canadian-owned firm that was brought by a Chinese conglomerate, CCRC-Tongguan Investment, in 2010. According to the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, the project will devastate around 450,000 acres of forest.

“This is a camouflaged crime,” said Ankuash. “In Ecuador, multinational companies are invited by the government and get full state security from the police and the army. The army and police don’t provide protection for the people, they don’t defend the Shuar people. They’ve been bought by the company.

“The authorities are complicit in this crime,” Ankuash claimed. “They will never tell us the truth.” He added: “[Tendetza] was not just anyone. He was a powerful leader against the company. That’s why they knocked down his house and burnt his farm.

“The government will never give us a response, justice belongs to them. They will call us terrorists but that doesn’t mean we are not going to shut up.”

Several other Shuar opponents of Mirador have died as a result of the conflict in recent years, including Bosco Wisum in 2009 and Freddy Taish in 2013, according to Amazon Watch.

An initial autopsy said the circumstances of Tendetza’s death were unclear. Harold Burbano, of the human rights organisation INREDH, said there was a suspicion that the killing was related to his work as a land defender.

“There has been a rise of conflicts since the transnational mining company entered the area, significantly increasing the risks faced by community leaders,” he said.

Tendetza had planned to condemn the project at a Rights of Nature Tribunal organised by NGOs at the climate talks which are taking place this week in the Peruvian capital.

Luis Corral, an advisor to Ecuador’s Assembly of the People of the South, an umbrella group for indigenous federations in southern Ecuador, said that if Tendetza had been able to travel to the COP20 it would have put in “grave doubt the honorability and the image of the Ecuadorean government as a guarantor of the rights of nature”.

“We believe that this murder is part of a pattern of escalating violence against indigenous leaders which responds to the Ecuadorean government and the companies’ need to clear the opposition to a mega-mining project in the Cordillera del Condor,” he said.

“The state through the police and the judiciary is involved in hiding this violent crime because of the elemental irregularities in the proceedings. The body was buried without informing the family. They weren’t allowed to see the second autopsy.”

Tendetza’s killing highlights the risks facing environmental activists in Ecuador. Earlier this week, a group of campaigners travelling in a “climate caravan” were stopped six times by police on their way to Lima and eventually had their bus confiscated.

The activists said they were held back because president Correa wants to avoid potentially embarrassing protests at the climate conference over his plan to drill for oil in Yasuni, an Amazon reserve and one of the most biodiverse places on earth.

Once lauded for being the first nation to draw up a “green constitution”, enshrining the rights of nature, Ecuador’s environmental reputation has nosedived in recent years as Correa has put more emphasis on exploitation of oil, gas and minerals, partly to pay off debts owed to China.

From The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/06/ecuador-indigenous-leader-found-dead-lima-climate-talks

by DGR News Service | Apr 21, 2014 | Repression at Home

By Jeremy Hance / Mongabay

At least 908 people were murdered for taking a stand to defend the environment between 2002 and 2013, according to a new report today from Global Witness, which shows a dramatic uptick in the murder rate during the past four years. Notably, the report appears on the same day that another NGO, Survival International, released a video of a gunman terrorizing a Guarani indigenous community in Brazil, which has recently resettled on land taken from them by ranchers decades ago. According to the report, nearly half of the murders over the last decade occurred in Brazil—448 in all—and over two-thirds—661—involved land conflict.

“There can be few starker or more obvious symptoms of the global environmental crisis than a dramatic upturn in killings of ordinary people defending rights to their land or environment,” said Oliver Courtney of Global Witness. “Yet this rapidly worsening problem is going largely unnoticed, and those responsible almost always get away with it. We hope our findings will act as the wake-up call that national governments and the international community clearly need.”

But as grisly as the report is, it’s likely a major underestimation of the issue. The report covers just 35 countries where violence against environmental activists remains an issue, but leaves out a number of major countries where environmental-related murders are likely occurring but with scant reporting.

“Because of the live, under-recognized nature of this problem, an exhaustive global analysis of the situation is not possible,” reads the report. “For example, African countries such as Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and Zimbabwe that are enduring resource-fueled unrest are highly likely to be affected, but information is almost impossible to gain without detailed field investigations.”

In fact, reports of hundreds of additional killings in countries like Ethiopia, Myanmar, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe were left out due to lack of rigorous information.

Even without these countries included, the number of environmental activists killed nearly approaches the number of journalists murdered during the same period—913—an issue that gets much more press. Environmental activists most at risk are people fighting specific industries.

“Many of those facing threats are ordinary people opposing land grabs, mining operations and the industrial timber trade, often forced from their homes and severely threatened by environmental devastation,” reads the report. “Indigenous communities are particularly hard hit. In many cases, their land rights are not recognized by law or in practice, leaving them open to exploitation by powerful economic interests who brand them as ‘anti-development’.”

As if to highlight these points, Survival International released a video today that the groups says shows a gunman firing at the Pyelito Kuê community of Guarani indigenous people. The incident injured one woman, according to the group. The Guarani have been campaigning for decades to have land returned to them that has been taken by ranchers.

“This video gives a brief glimpse of what the Guarani endure month after month—harassment, intimidation, and sometimes murder, just for trying to live in peace on tiny fractions of the ancestral land that was once stolen from them,” the director of Survival International, Stephen Corry, said. “Is it too much to expect the Brazilian authorities, given the billions they’re spending on the World Cup, to sort this problem out once and for all, rather than let the Indians’ misery continue?”

According to the report, two major drivers of repeated violence against environmental activists are a lack of attention to the issue and widespread impunity for perpetrators. In fact, Global Witness found that only ten people have been convicted for the 908 murders documented in the report, meaning a conviction rate of just 1.1 percent to date.

“Environmental human rights defenders work to ensure that we live in an environment that enables us to enjoy our basic rights, including rights to life and health,” John Knox, UN Independent Expert on Human Rights and the Environment said. “The international community must do more to protect them from the violence and harassment they face as a result.”

From Mongabay: “Nearly a thousand environmental activists murdered since 2002“