by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 22, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: Residents of Kiad around an important boundary post for the Ngäbe people at the border of the comarca. (Photo courtesy Duiren Wagua)

Este artículo está disponible en español aquí

by Tracy Barnett / Intercontinental Cry

Cultural Community of Kiad, Panama — Members of the grassroots indigenous Ngäbe-Buglé group known as The April 10 Movement (El Movimiento 10 de Abril, or “M10”), issued a call to the international community on Wednesday. They ask for an intervention to stop Ngäbe-Buglé communities from being flooded by the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam.

The M10 called the flooding illegal and a violation of their human rights and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They refer to an environmental impact statement that failed to acknowledge the presence of the three communities that would be flooded by the project. They also say the agreement that Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela signed last August with the now-impeached leader Silvia Carrera was illegal, since it was done without the approval of the Ngäbe-Buglé General Congress, and was rejected by the congress in September.

Government representatives met with members of the group in the Cultural Community of Kiad on March 27. It was part of a series of meetings “to agree on options with respect to spaces and points of cultural veneration by communities impacted by the project and the monitoring of water quality studies,”[1] according to an institutional response from the government. Several days later, the water began to rise in the reservoir and has continued to rise until the time of publication of this communique. Community members have still not received communication from the government regarding the rising water levels or a future meeting date.

Communiqué from the April 10 Movement on the Barro Blanco hydroelectric plant

The community affected by the Hydroelectric Project Barro Blanco, hereby makes public the following facts of the violation of human rights by the Barro Blanco Dam:

1- As has been public knowledge since the beginning of the Barro Blanco project, the environmental impact study denied the existence of the original community that for centuries had lived in the confluence of the Tabasará River, and concessioning this place for the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam has created a social, economic, cultural, spiritual, and environmental conflict for the community.

2- The government and the Supreme Court of Justice have violated the constitutional and legal precepts of our rights with the implementation of the Barro Blanco hydroelectric plant.

3- We firmly reject the ratification of the Varela-Carrera agreement for the defunct congress presided over by Demecio Case, held between 6 and 9 April 2017 in the northern community in the ñökribo region, in which agreement we played no part. Nor were we consulted about the content of the agreement, and the agreement was not accepted by the population of Llano Tugrí on August 22, 2016 and was rejected in Cerro Algodón on September 15, 2016 by the full General Congress where 148 delegates attended.

4- The highest body of expression and decision, the General Congress, has 255 elected delegates, with full right of decision and for which quorum constitutes 50% plus one; therefore the Norteño decision is illegal, since only 61 delegates attended, in addition to Mr. Demecio Case, who was removed from office on March 7, 2017, in Llano Tugrí, in the ordinary congress.

5- We request the President of the Republic to be a little more respectful of our rights, since any act carried out for the execution of said project has been done violating our legal security, and not only has violated the norms of the Republic, but also violated the Convention and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

6 – We call on the Panamanian population to protect the rights of all before the imposition of the government who makes use of economic and political power and interferes in the decision of the full Congress through the dismissal of Silvia Carrera and Demecio Case.

7- We make an urgent appeal to the national and international solidarity organizations and the United Nations to intervene to protect our rights as peoples most vulnerable to deserved justice in the Republic of Panama.

Gäejet Miranda

President of the M10 movement

Ngäbe-Büglé Comarca

Kiad Cultural Community, April 16, 2017

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 30, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Dozens of people have been shot on sight by park guards in Kaziranga, including severely disabled tribal man Gaonbura Killing. © BBC

by Survival International

Survival International has called on the UN expert on extrajudicial executions to condemn shoot on sight conservation policies.

In a letter to the Special Rapporteur charged with the issue, Survival stated that “shoot on sight policies directly affect tribal people who live in or adjacent to ‘protected areas’… particularly when park guards so often fail to distinguish subsistence hunters from commercial poachers.”

The letter adds that “nobody knows when wildlife officers are permitted to use lethal force against [suspected poachers], and it is impossible for dependents to hold to account officers whom they believe to have killed without good reason. Many countries have gone further, and granted wildlife officers immunity from prosecution.”

The letter cites Kaziranga National Park in India as an especially striking example of the tactic. According to a recent BBC report, an estimated 106 people have been extrajudicially executed there in the last 20 years, including one disabled tribal man who had wandered over the park boundary to retrieve cattle.

Kaziranga guards have effective legal immunity from prosecution, and have admitted that they are instructed to shoot poaching suspects on sight. This has had serious consequences for tribal peoples living around the park. In June 2016, a seven-year-old tribal boy was shot and maimed for life by guards.

Akash Orang is comforted by his mother after being shot by a park guard. He is now severely disabled. © BBC

Similar policies are used in other parts of the world, notably Kenya, Tanzania and Botswana, among other African countries.

Speaking about his own anti-poaching work in Africa, poaching expert Rory Young from the organization Chengeta said: ”Shoot on sight is stupid. If we had been shooting on sight during this latest sting operation we would have shot a handful of poachers and that would have been the end of it. Every single poacher is an opportunity for information to get more poachers and work your way up the chain to the ringleaders.”

Survival has asked the Special Rapporteur to clarify that shoot on sight violates fundamental rights enshrined in the UN’s Civil and Political Rights Covenant and other international conventions. It also urges the UN to enquire about the policy with the Indian government, and the government of Assam state, where Kaziranga is located.

Shoot on sight is justified on the grounds that it helps to deter poachers. However, there have been several recent cases of guards and officials at Kaziranga being arrested for involvement in the illegal wildlife trade themselves.

Survival International is leading the fight against these abuses, and calling for a new conservation model that respects tribal peoples. Targeting tribal people diverts action away from tackling the true poachers – criminals conspiring with corrupt officials. Targeting tribal people harms conservation.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “If any other industry was guilty of this level of human rights abuses, there would be an international outcry. Why the silence when conservationists are involved? Torture and extrajudical killing is never justified – the law is clear on this. Some people think that the death of innocents is justified, that ‘collateral damage’ is necessary in the fight against poaching. We ask them, where is your humanity? Of course, there’s a racist element at play here: Shoot on sight policies would be unthinkable in North America or Europe.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 26, 2017 | Indigenous Autonomy, Obstruction & Occupation

Featured image: Protesters gathered at Los Encuentros, by Anna Watts

by Anna Watts / Intercontinental Cry

Indigenous communities across Guatemala have brought the country to a standstill for the second day in a row. Blockading major crossroads and highways, the nationwide peaceful demonstrations are protesting against the Guatemalan congress’s rejection of a constitutional reform that would legally recognize indigenous justice as part of the country’s judicial system.

An estimated 60 percent, or more than 6 million inhabitants, make up Guatemala’s population (IWGIA). Yet indigenous systems of justice, wherein local authorities rule on community issues, have been looked down upon by a country that continues to hugely discriminate against its majority indigenous population. The reforms face opposition from conservatives and major businesses that control most of Guatemala’s land and economy. Although many of these business interests campaigned against the reforms under the guise of fearing “legal confusion,” indigenous activists and leaders at the protests describe the opposition as deriving from a fear of losing any of their elite power to those who have been oppressed and exploited for centuries–Indigenous Peoples.

Photo: Anna Watts

At Los Encuentros, one of the most important crossroads between major cities located along the Pan-American Highway, thousands of indigenous people of the Sololá region gathered to participate in the blockades. Carrying handmade signs and led by their respective indigenous leaders, community groups unloaded from packed cargo trucks and chicken buses, carrying ready-made lunches to last through a full day of protesting.

By 8:30 AM, every tienda, comedor, and tortilla stand had been closed down and locked up, a rare sight for the ever-bustling highway hub. The majority indigenous city of Sololá was deserted; not a car in sight nor shop windows open. Pick-up trucks and makeshift blockades of boulders and large tree branches cut off traffic between smaller communities surrounding Lake Atitlán.

Protesters organized and coordinated solely by means of meetings and phone calls between indigenous community leaders. Use of Internet or social media to communicate and gain protest support was entirely avoided out of fear of vulnerability and tracking by police and those opposing the reforms. This distrust was reflected in weak media coverage of the protests; in spite of the thousand plus standing in solidarity at Los Encuentros, only one reporter from a local agency showed up with a small video camera.

Photo: Anna Watts

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 16, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Kaziranga park guards are heavily armed and instructed to shoot intruders on sight. © Survival International

by Survival International

A BBC investigation has revealed that tribal peoples living around a national park in India are facing arrest and beatings, torture and death under the Park’s notorious “shoot-on-sight” policy.

The report for television, radio and the BBC news website featured interviews with park guards, tribal people who have been affected by the policy in Kaziranga National Park, and a spokesman from WWF-India, which helps fund, train and equip park guards and advertises tours of the park through its website.

The park gets over 170,000 visitors each year. Fifty suspects were extrajudicially executed there in the last three years, and a severely disabled tribal man was shot dead in 2013. The BBC has estimated that 106 have been killed in the last 20 years. In the same period, only one official has been killed.

The BBC interviewed one local man who had been beaten and tortured with electric shocks during a detention by park officials before they realized he had no involvement in poaching.

The program also featured Akash Orang, a seven-year-old tribal boy who was shot in the legs by park guards last July. Akash said that: “The forest guards suddenly shot me” as he was on his way to a local shop. His father said: “He’s changed. He used to be cheerful. He isn’t any more. In the night, he wakes up in pain and he cries for his mother.”

Park guards have effective immunity from prosecution and are encouraged to shoot suspects on sight – without arrest or trial, or any evidence that they might have been involved in poaching. One guard admitted that they are: “Fully ordered to shoot them, whenever you see the poachers or any people during night-time we are ordered to shoot them.”

WWF has provided equipment – including what the BBC calls “night vision goggles” – which have been used in night-time operations and “combat and ambush” training. When asked by the BBC how donors might feel about their money being used to enforce this brutal treatment, WWF India’s spokesman said that: “What is needed is on-ground protection… We want to reduce poaching and the idea is to reduce it with involving other partners.”

Survival International is leading the global fight against these abuses and first brought the park’s high death toll and serious instances of corruption among Kaziranga officials – including involvement in the illegal wildlife trade they are employed to stop – to global attention in 2016.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “Conservation organizations, including WWF, are supporting a model of conservation which is resulting in gross human rights abuses. They have failed to condemn policies that are leading to widespread extrajudicial executions. For too long, conservation has relied on its positive public image to hide its horrific and sustained attacks on indigenous and tribal peoples’ rights. We’re working to stop this. It’s time for conservationists to work with tribal people, the best conservationists and guardians of the natural world. It’s time for conservation organisations to call for an end to shoot on sight policies.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 24, 2017 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

Featured image: A Yukpa woman tends laundry high in the clouds of the Yukpa lands, which rise over 3000 meters in the Sierra Perijá on the border of Colombia and Venezuela.

by Nicholas Parkinson / Intercontinental Cry

A community of indigenous Yukpa saw their land reduced to a third of what it once was due to violence and intimidation. Now Colombia’s Land Restitution Unit is helping the community return to their lands.

The spiritual equilibrium essential to the Yukpa community is off balance. Ancestral burial grounds have been desecrated by invaders; the trees that house the spirits are being cut down; and the wild game that Yukpa men once hunted with zeal is no longer available. The same limitations preventing the community from practicing its culture are preventing Yukpa parents from passing these activities, words, and stories down to new generations.

“The loss of culture is very real. Our children won’t know anything about the Yukpa if we aren’t rescued from extinction. If we don’t have space to preserve our culture, I guarantee that in thirty years, our culture will disappear,” says Andrés Vence, council leader of a Yukpa community consisting of 120 families living on 300 hectares in the Sierra Perijá on the border of Venezuela and Colombia.

“Culture’s longevity depends on territory.”

The yukpa believe that land is the key to allowing their culture, customs and beliefs to flourish.

There are an estimated 6,000 Yukpa remaining in Colombia, and the majority live on autonomous lands known as resguardos. Over the past thirty years, the Yukpa community living in La Laguna has been victim to abuse and intimidation stemming from the armed conflict. The community has also seen its ancestral lands become increasingly occupied by “outsiders,” whom they refer to as colonists. Now, the community is pushing back by launching an ethnic restitution claim that seeks to recover 964 hectares of land and allow the community the space it needs to flourish.

HUMILIATION AND ABUSE

In 1982, the guerrilla group known as the FARC came to Yukpa territory to recruit. Andrés Vence was abducted for eight days to be indoctrinated. He and the Yukpa resisted, but then another guerrilla group known as ELN arrived the following year. After the ELN abducted several young men, Vence and his men–armed with just bows and arrows–marched into the guerrilla camp and took their children back, saying the Yukpa would not participate in any war.

A Yukpa security guard, still armed with bow and arrow.

When the Colombian military entered the scene in the mid-1990s, the situation turned for the worst. Yukpa families could no longer move freely from house to house, leading to the systematic abandonment of more than 900 hectares of land. For years, military checkpoints restricted the flow of food between families. As if that wasn’t bad enough, paramilitary groups—who were often the same members of the military—came to the Yukpa villages at night to terrorize the community.

“They abused and humiliated us,” says Vence. “I think it was all in the hopes that we would open our mouths and say something that gave them the right to murder us.”

Andrés Vence, mayor and leader of the Yukpa community making the restitution claim.

DOCUMENTED HISTORY

In 2015, the regional Land Restitution Unit (LRU) in Cesar focused on “characterization studies,” an essential piece of evidentiary material that documents the background, victimization, and suffering of indigenous communities who wish to reclaim their land. Characterization is a critical step in substantiating an ethnic restitution claim. The USAID-funded Land and Rural Development Program* partnered with the LRU to expedite the process.

Over the course of six months, researchers visited the Yukpa, where they interviewed individual members and held focus groups. They also collected materials from the government, non-governmental organizations, academic texts, and the media. The end result was nearly 200 pages of history, mapping, experience, and evidence presenting how the armed conflict contributed to the decimation of the Yukpa’s culture, livelihood, and overall prosperity.

In addition to carrying out the characterization studies, USAID helped regional restitution offices improve coordination with partner members of the Victims Assistance and Comprehensive Reparations System and municipal officials.

“The partnership gave us operating capacity. Without this support, we would have taken another one or two years to get to this case,” says Jorge Chávez, Director of the Land Restitution Unit in Cesar.

The document will be filed as part of the Yukpa community’s land restitution claim, which will go before a restitution judge before the end of the year. By law, judges must issue a ruling within six months after a restitution claim is filed in the court. In Cesar, the Yukpa case will be the third ethnic restitution case to reach the courts, making the department an important player in the nationwide effort to heal the historic rift between the government and Indigenous Peoples.

Colombia’s indigenous communities are often the country’s most vulnerable. Over the past five years, Colombian restitution judges have issued three ethnic restitution sentences, delivering over 124,000 hectares of land back to indigenous communities.

There are currently over 24 ethnic restitution cases in the characterization phase that stand to affect over 10,000 families in Colombia.

“All over the country, there are ethnic restitution cases reaching judges. The LRU is in its fifth year and these cases are becoming more and more important to resolve. This particular case is very important because the Yukpa are losing their cultural identity, and we recognize that,” according to Chávez.

In its five years, restitution judges have issued three ethnic restitution sentences, delivering over 124,000 hectares of land back to indigenous communities.

As the Yukpa wait on the judge’s ruling, the case’s progress has emboldened Vence to mobilize the community—including the older citizens known as Yimayjas—to transmit the collective memory and cultural skills like weaving mochilas, practicing spiritual rites, and crafting shields to fend off malignant spirits.

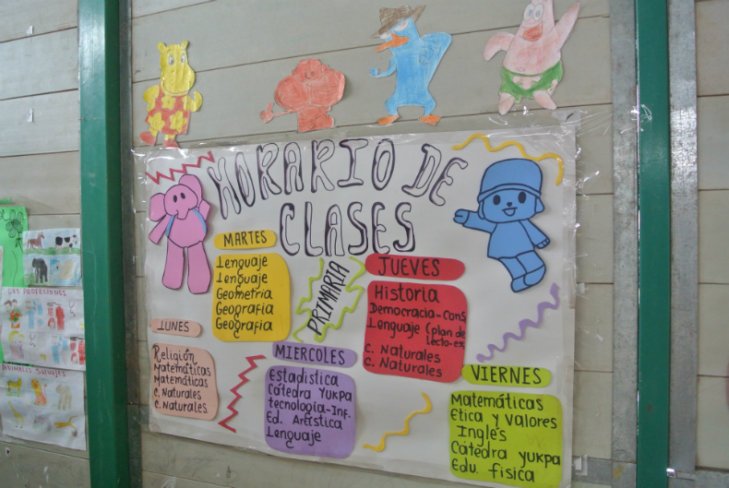

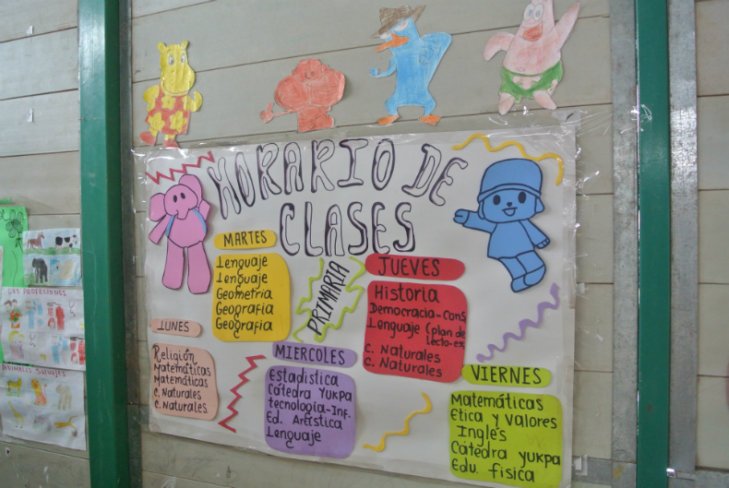

Every Wednesday and Friday, Yukpa children attend “Yukpa studies” at the only school in the resguardo.

A favorable ruling will be key to restoring Yukpa faith in the Colombian government. “We’ve put pressure on the government for many years to do this, so our hope is temporary. We watch television, and indigenous culture is never part of the conversation. Indigenous communities are the most vulnerable,” explains Vence.

* Nicholas Parkinson works for the Land and Rural Development Program.

Nicholas is an NGO writer currently based in Bogota, Colombia and working on a large land tenure program that sets out to strengthen government land administration agencies to better serve millions of victims displaced by the violence. Over the past six years, he has worked mainly on agriculture-focused projects in Ethiopia, Liberia, Uganda and Somalia, among others. He specializes in NGO documentation and teaches local writers how to create attention-grabbing stories for their NGOs. On his weblog you can find stories from his immigrant life, some thoughts on development aid, and a strong dose of rock climbing and adventure.