by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 21, 2016 | Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home

by Indigenous Environmental Network

Cannon Ball – On November 20th at approximately 6PM CST over 100 Water Protectors from the Oceti Sakowin and Sacred Stone Camps mobilized to a nearby bridge to remove a barricade that was built by the Morton County Sheriff’s Department and the State of North Dakota. This barricade, built after law enforcement raided the 1851 treaty camp, not only restricts North Dakota residents from using the 1806 freely but also puts the community of Cannon Ball, the camps, and the Standing Rock Tribe at risk as emergency services are unable to use that highway.

Water Protectors used a semi-truck to remove two burnt military trucks from the road and were successful at removing one truck from the bridge before police began to attack Water Protectors with tear gas, water canons, mace, rubber bullets, and sound cannons.

At 1:30am CST the Indigenous Rising Media team acquired an update from the Oceti Sakowin Medic team that nearly 200 people were injured, 12 people were hospitalized for head injuries, and one elder went into cardiac arrest at the front lines. At this time, law enforcement was still firing rubber bullets and the water cannon at Water Protectors. About 500 Water protectors gathered at the peak of the non-violent direct action.

The following is a statement from the Indigenous Environmental Network:

“The North Dakota law enforcement are cowards. Those who are hired to protect citizens attacked peaceful water protectors with water cannons in freezing temperatures and targeted their weapons at people’s faces and heads.

“The Morton County Sheriff’s Department, the North Dakota State Patrol, and the Governor of North Dakota are committing crimes against humanity. They are accomplices with the Dakota Access Pipeline LLC and its parent company Energy Transfer Partners in a conspiracy to protect the corporation’s illegal activities.

“Anyone investing and bankrolling these companies are accomplices. If President Obama does nothing to stop this inhumane treatment of this country’s original inhabitants, he will become an accomplice. And there is no doubt that President Elect Donald Trump is already an accomplice as he is invested in DAPL”.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 15, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest

If treaties are the supreme law of the land, as the U.S. Constitution states, then how is it that treaties can be so easily broken by a government that claims to uphold a respect for the law? An even more unsettling question: how is it that the trail of broken treaties has been able to span generations under an outdated, imperial logic unknown to the majority of the U.S. citizens? The founding of the United States is predicated on this painful contradiction between principles of equality and rule of law on one side, and the colonial appropriation of land from native peoples who have inhabited them for millennia, on the other.

The current resistance against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) is inscribed in this contradiction, making evident the non-rule of law when it comes to appropriating native lands.

The history of Standing Rock is marked by the history of colonization predicated on the Doctrine of Discovery. The progressive erosion of its Sioux territory goes hand in hand with the logic of terra nullius, which framed land in the Americas as “empty” in order to justify settler colonization.

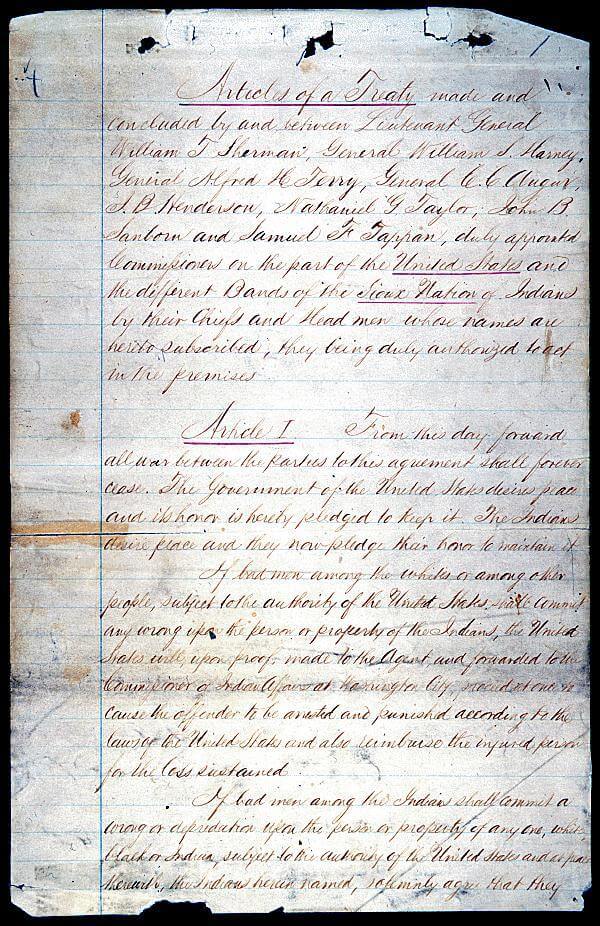

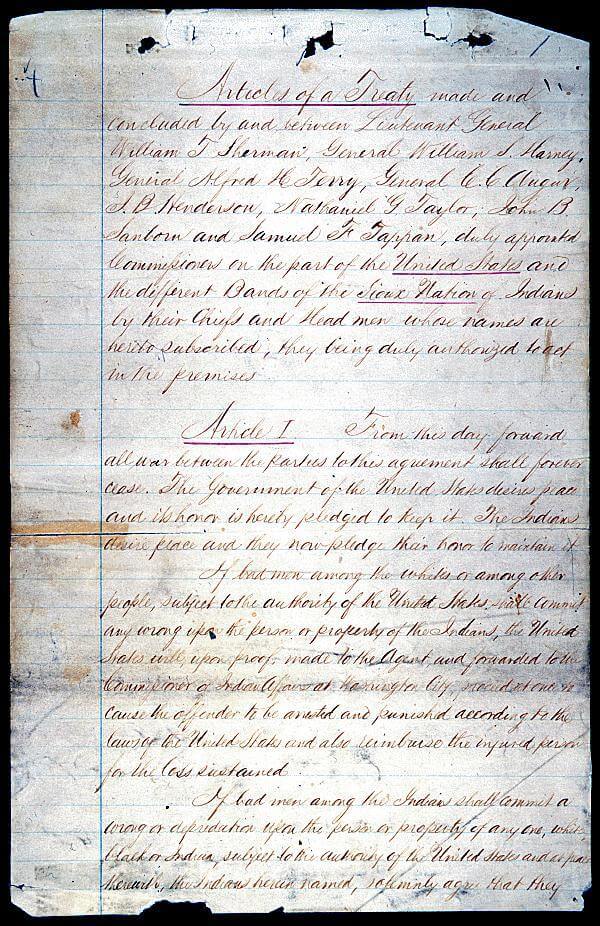

The Sioux Nation has historically engaged in sovereign government-to-government relations with the US government. The first treaty in which the two parties engaged as diplomatic equals was the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851. It was the U.S. government who sought the treaty to allow for safe passage of the influx of settlers travelling west through Sioux territory during the Gold Rush from the east coast to California.

The process of negotiating the Treaty of Fort Laramie followed the colonial settler standard used in contemporary treaty negotiations. While the process was equal in theory to the traditional communal decision-making processes under which many Native Nations operated, the colonial method, which uses elected representatives, heavily favored the interests of the colonial government. Ultimately, the treaty established distinct territories for just under 10 Great Plain tribes. The treaty also permitted settlers to travel on the Platte River Road, achieving the U.S. government’s goal.

The 1851 treaty defined Sioux territory as the land where the DAPL is now being constructed. The territory fell within the western half of modern South Dakota, northwest Nebraska, a portion of northeast Wyoming, and a small part of southeast Montana and southwest North Dakota.

From the very beginning, various parties continuously broke the Treaty of Fort Laramie. Many tribes, unaware of the existence of the treaty, continued to carry out raids on tribes on legally different territories. Furthermore, settlers increasingly trespassed into the treaty territories, disrupting the buffalo hunting grounds of Native Nations. The settlers’ wrongful presence on native land led to various hostile skirmishes and bloody battles in which natives were massacred often without provocation.

But the violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie didn’t stop there. Over the years, the U.S. government has continued to appropriate Sioux land in an ongoing process of colonization that disregards the treaty. (See map.)

In 1861, the discovery of gold in present-day Montana accentuated the flood of fortune-seekers overrunning Sioux lands in violation of the decade-old Laramie Treaty. Sioux protests to defend their rights and territory were ignored, so the Sioux took matters into their own hands to stop the trespassers. The U.S. responded by sending in a military presence.

Instead of adhering to the terms of the treaty, the U.S. government attempted to negotiate another treaty more preferential to its interests. Treaty making, instead of a diplomatic engagement between two equally powerful sovereign nations had turned into a destructive means of grabbing land and resources from native people; a form of “conquest by law” as per the book by Lindsay G. Robertson.

The result was a second treaty of Fort Laramie signed in 1868. This new treaty shrank the territorial boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation in exchange for the U.S. federal government’s removal of all existing forts in the Powder River area, among other specifications. Yet it was a flawed treaty from the start. Most importantly, it stipulates that no changes can be made to the legally binding agreement unless ¾ of all adult Sioux males consent. Many members of the Sioux nation, particularly those within the boundaries of the territory signed the treaty. But many more bands residing north of the Bozeman Trail, such as the Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands, did not. The treaty was not signed by three quarters of all adult Sioux males.

Yet, again, the U.S. government violated the treaty. The second Laramie treaty granted the tribes the right of regulating the entry of persons into their territory. Article II of the 1868 Treaty stipulates that nobody can enter the territory without tribal permission. But time and time again settlers have encroached on Sioux territory.

Some Americans may know that in 1874 the U.S. government sent George Custer with a group of scientists to search for natural resources, especially gold, in the isolated mountain range known today as the Black Hills. The gold they found led to an influx of miners, again in direct violation of the treaty.

Eventually, the U.S. government decided to pursue its strategy of land appropriation without bothering with the pretense of legality. The Sioux learned to be wary of treaties with the U.S. and refused to sign away their land.

In 1877, Congress unilaterally passed an act removing the sacred Black Hills from the Great Sioux Reservation, without the ¾ consent of the Sioux mandated by the Laramie Treaty of 1868. This illegal grab of sacred land brought no legal repercussions to the party that violated the treaty—the U.S. government.

In 1889, Congress again diminished the Great Sioux Reservation with the Dawes Act and Allotment Act, partitioning it into six sections, one of which was the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. This opened up parts of the reservation to outside settlement, even though the native government still controls all reservation lands.

Sioux struggles for water are embedded in such displacements. In 1948, the U.S. government began construction of Oahe Dam, despite resistance from local tribes. Its creation flooded tribal land and forced a quarter of the reservation’s inhabitants to move.

In 1958, a federal court ruled that Lake Oahe was part of the Standing Rock territory according to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. In this ruling the court said, “Where there is a treaty with Indians which would otherwise restrict the Congress, Congress can abrogate the treaty in order to exercise its sovereign right.” The court openly articulated the self-arrogated right of the U.S. government to go back on treaty obligations with Native Americans to unilaterally exercise its sovereign power.

The U.S. did just that, taking the Lake Oahe land from the Standing Rock tribe through legislation passed by Congress in September 1958 [Public Law 85-915].

Legal abrogation, or repealing legislation, dispenses with any idea of fair treaty making between equals. It undermines native sovereignty, following a racist logic of colonial elimination. It dispenses with numerous prior legal precedents that granted Native Americans some rights, such as the Indian Appropriations Act of 1871, which declared that no treaty obligation with an Indian nation before March 3, 1871 can be “invalidated or impaired.” It puts into question the idea of the “federal Indian trust responsibility,” articulated in the Seminole Nation v. United States case of 1942, which entailed an obligation on the part of the U.S. government to protect tribal treaty rights, land, assets and resources, per the Department of the Interior Indian Affairs branch.

As a federally recognized tribe, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is legally entitled to these obligations. However, as history has shown, U.S. principles and laws do not seem to have the same meaning when it comes to Native Americans.

The United States claim that it can abrogate treaties with Native Americans has been upheld by US courts as legal. Law in our modern eyes carries the weight of legitimacy.

But because something is legal does not make it right. In the case of the Sioux, alongside every other Native American nation, laws and treaties have all too often been used not as a protective shield, or even as a neutral arbitrator, but as a weapon. That weapon is predicated on a racist, colonial history that invalidated native people’s rights to their land, to their sovereignty, to their cultural expression, to their very lives.

Whether it is the gold rush or the oil rush, the U.S government continues even now to invade native land and break treaties. The proposed DAPL would pass under Lake Oahe, the land that was openly, “legally” taken from the Sioux tribe in 1958 by Congress, despite the prior 1868 Treaty that had legally granted the Sioux rights to the land.

Today’s protests at Standing Rock today can only be fully understood in light of this colonial legacy, which from the beginning proclaimed that native lands were empty and that native people, were, in effect, nothing more than the rocks, the trees, the water that they now so valiantly strive to protect.

Let us fight against this narrative, and show through Standing Rock that native tribes are sovereign nations that possess the inherent right to life on their territories. Let us show that Native American lands are not empty, but that proud sovereign peoples live there, alongside the earth, water, rocks and trees, wind and sky, encompassing a vibrant fullness in their long defense of life.

There never was terra nullius. The only emptiness to be found exists in the hollow promises of the United States, in the historic lack of equitable substance in the U.S. legal system.

In that spirit, many U.S. citizens are now, finally, refusing to turn a blind eye to the trail of broken treaties. They stand with Standing Rock, and are petitioning President Obama to honor the treaties (petition here): “The Native nations have upheld their end of the bargain; it is time the U.S. government did the same.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 14, 2016 | Lobbying

by Cultural Survival

“We call upon all member states, to condemn the destruction of our sacred places and to support our nation’s efforts to ensure that our sovereign rights are respected. We ask that you call upon all parties to stop the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline and to protect the environment, our nation’s future, our culture and our way of life.”

– Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Chairman Dave Archambault II

The International Indigenous Peoples`Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC) condemns the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline and stands in solidarity with our sisters and brothers of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and all Water Protectors in opposition to this project.

Human Rights and the Indigenous Rights Perspective

The Dakota Access pipeline is being built on the un-ceded treaty lands of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, without their free, prior and informed consent, as is described in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Articles 18, 19, and 32. The pipeline is also being constructed through sacred areas and ancestral burial grounds of the Standing Rock Sioux and other Indigenous Peoples of the area. This massive construction project does not respect the Standing Rock Sioux’s Treaty rights, sovereignty, or their right to self-determination. It is an outright violation of their rights over their lands and resources as Indigenous Peoples, and does not respect the human rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Climate Perspective

The Dakota Access pipeline will transport 470 000 – 570 000 barrels of oil every day, which will release emissions of 101,4 million tonnes CO2, as much as 30 American coal power plants, every year. This is not consistent with the State Parties’ obligations and commitments under the Paris Agreement or the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The continued production of fossil fuels only assures that global temperature will rise well above 2°C in the immediate future and threaten the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples around the world. The potential for a major oil spill from the Dakota Access pipeline is immediate. The pipeline is scheduled to cross underneath the Missouri River, which is the main source for drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and for millions of people who live downstream. Sunoco Logistics, the operating company of the pipeline, alone has experienced over 200 oil spills in 6 years, and the US had in total over 3300 leaks since 2010, polluting rivers, ground waters, land and air, and both human lives, health and livelihoods has been lost.

The IIPFCC calls upon the US to halt the construction of the Dakota Access pipeline and to enter into serious consultations with the Standing Rock Sioux, and other tribes affected by this project, respecting the right of the Tribes to free, prior and informed consent.

The state owned Norwegian Oil Fund is heavily invested in the pipeline. The IIPFCC calls upon Norway to divest from the Dakota Access pipeline Project.

We also call on all States to ensure the protection of Indigenous Peoples´ territories across the world as a critical action in the implementation of the Paris Agreement and in achieving the SDGs.

Featured image by A. Golden/Flickr.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 18, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy

by Emmy Keppler / Intercontinental Cry

On October 13, the 500 delegates of the National Indigenous Congress (CNI) reached complete consensus on the proposal presented by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) at the opening of the fifth Congress three days earlier: the CNI will collectively enter the 2018 Mexican presidential race with an indigenous woman candidate at its forefront.

The Fifth Congress is now in permanent assembly while the delegates return to their communities and hold consultations to decide to either approve or reject the proposal.

This decision represents a major shift in strategy of the Zapatista movement which in 2003, after nine years of betrayed negotiations with the Mexican government, cut off all communication with the political system. In the subsequent thirteen years they have not looked back, focusing instead on constructing autonomy in their own communities. The proposed presidential campaign will not, however, be a return to engagement with the political system, but rather a takeover and, if successful, dismantling of that system.

“We confirm that our fight is not for power, we do not seek it; rather we call all of the original peoples and civil society to organize to detain this destruction, to strengthen our resistances and rebellions, that is to say in the defense of the life of each person, family, collective, community, or neighborhood. To construct peace and justice, reconnecting ourselves from below,” stated the CNI and EZLN in a communiqué released at the closure of the assembly.

The Indigenous Council of Government will be made up of representatives from CNI communities from all states and regions of Mexico, with the individual candidate serving to “make their [collective] word material.”

THE FIGHT FOR RECOGNITION

The CNI was formed in 1996, nearly two years after the indigenous Zapatistas of Chiapas famously rose up in arms and declared war on the Mexican government. Earlier that same year, the EZLN and federal government signed the San Andrés Accords, which agreed to recognize indigenous autonomy in the constitution, increase indigenous political representation, and guarantee access to justice.

In October of that year, thousands of indigenous people from communities all over the country gathered in Mexico City for the first National Indigenous Congress, agreeing that their primary objective would be to defend the San Andrés Accords. It was at this first Congress that the late EZLN commander Ramona declared what soon became the slogan of the CNI: “NEVER AGAIN A MEXICO WITHOUT US.”

When the EZLN and government met to finalize the Accords one month later, a familiar pattern of denial began to re-emerge: The government refused to sign the Accords. Simultaneously, then president Ernesto Zedillo launched a bloody militarization campaign throughout Chiapas climaxing in the Acteal Massacre in which paramilitary troops massacred 45 members of Las Abejas, an indigenous Catholic pacifist organization.

The primary focus of both the EZLN and the CNI, then, became an effort to push the Mexican government to pass the Accords. In 2001, the third National Indigenous Congress was held in the Purépucha community of Nurío in Michoacán. Representatives from 40 of Mexico’s 57 Indigenous Peoples created a list of demands including constitutional recognition of indigenous rights and autonomy, and the recognition of indigenous systems of justice and ancestral territory.

That same year, Comandanta Esther addressed the Congress of the Union: “When indigenous rights and culture are constitutionally recognized in accord with the [San Andrés Accords], the law will begin joining its hour with the hour of the Indian peoples.”

The following month, Congress unanimously approved a constitutional reform concerning indigenous rights and culture that ignored all demands for autonomy and recognition, completely undermining the San Andrés Accords and cementing the betrayal of Indigenous Peoples by the entire Mexican political system.

It was after this ultimate betrayal that the Zapatistas and CNI decided to turn their backs on the Mexican political system which refused to include them. Instead, they decided to take matters in their own hands and implement the San Andrés Accords themselves in their communities and territories. What the government refused to give them, they would build.

For the next thirteen years, the Zapatista communities of Chiapas and indigenous communities throughout Mexico worked to construct their own autonomy from the ground up.

ACHIEVEMENTS AND LIMITATIONS OF AUTONOMY

In this Fifth National Indigenous Congress, which also celebrated the 20th anniversary of the CNI, delegates shared the immense achievements of autonomy in their communities:

They have rebuilt their traditional farming structures using organic fertilizers and native seeds.

They have reconstituted their traditional governments, replacing the corrupt government authorities with elder councils and community assemblies.

They have built their own community police and self defense forces, ousting organized crime and replacing the similarly corrupt official police who often work with narcotraffickers.

They have created community radio stations to broadcast the truth, drowning out the lies and silence of corporate media which, in Mexico, is monopolized by the media empire Televisa.

They have recuperated territory that was violently expropriated by the government and large landowners.

They have created their own bilingual indigenous schools where students learn about colonialism, capitalism, and the history of their people.

They have revived their traditional medicine and built clinics where before people had no healthcare, fighting dependence on western medicine.

However, they have also faced extreme repression, plunder of their territories, and human rights violations. There was not a single community that did not speak of their fight against what they call ‘death projects’— mining, fracking, hydroelectric dams, gas pipelines, airport construction, highway construction — operated by foreign corporations which do not consult their communities before destroying their land.

They are fighting against agroindustrial chemicals and pesticides contaminating their land and waters, the destruction of their forests, the invasion of genetically modified seeds, and the privatization and expropriation of their sacred water and collectively-held territory.

They are fighting supposedly ‘green’ development in the form of wind farms and conservation reserves that expropriate their territory and farmland, often for the production of monocrops like African Palm.

They are fighting against cultural death— the tourism industry that pillages their sacred sites and perverts their traditions as attractions for foreigners, and the disappearance of their languages and clothing.

And they are fighting against literal death—the murder, disappearance, kidnapping, rape, imprisonment, and psychological warfare that all indigenous communities in resistance face at the hands of the military, police, and organized crime.

The nation is also on the brink of total privatization of the public sector with the 11 structural adjustments passed by President Enrique Peña Nieto in 2013. Though the the CNI can prevent these reforms from entering their communities on a certain level, they can not, through autonomy alone, halt the devastating impacts of the privatization of public healthcare, education, communication, energy, and housing, among others.

In this Fifth Congress, the delegates recognized that walking the path of autonomy, though remarkably successful on a local level, has not allowed the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico to truly unite. Building coalitions on statewide and even regional or municipal levels has proved exceedingly difficult with most communities remaining relatively isolated. Though they all face the same repression by corporations and the government, each community fights the same enemy from its different corner of Mexico, thus allowing what the Zapatistas call ‘the capitalist hydra’ to divide and conquer. As one delegate from Jalisco said, “they’re continuing to screw us.”

THE PROPOSAL

The proposal of the EZLN for the CNI to run a collective presidential campaign is an effort to halt the hydra. At first, nearly all of the delegates were doubtful. They expressed their concerns about sacrificing their autonomy to embark on the electoral route. All, however, also expressed their deep trust in the EZLN as their guide in the struggle and their willingness to be convinced. Throughout the three-day assembly this is exactly what happened.

One of the fundamental principles of both the CNI and the EZLN is that they do not aspire to take state power, which they view as inherently corrupt and oppressive. The delegates spoke of their commitment to this principle and their concern of sacrificing it. Through their discussions, however, they clarified that they would not aim to take power, but rather dismantle this power from below and to the left, from the poor and marginalized indigenous communities fighting for their dignity, freedom, and autonomy.

Another fundamental principle is their opposition to all political parties, which they view as the same elite oppressor class dressed in different colors. They clarified that they would not create a new political party, but rather an Indigenous Council of Government which, Subcommander Galeano (formerly Marcos), urged us not to confuse with an Indigenous Government Council, meaning that they are not trying to indigenize the current government, but rather build a new indigenous government that governs according to the principles of the EZLN and CNI:

- Serve, don’t self-serve

- Represent, don’t supplant

- Construct, don’t destroy

- Propose, don’t impose

- Convince, don’t defeat

- Go below, not above

- Govern by obeying

The EZLN is demanding that we disrupt our basic notions of what a government is and what a government can do. In indigenous communities throughout the country as well as in Zapatista territory, the CNI has expelled government officials and revived their traditional systems of self-governance. The EZLN is asking us to envision this happening on a national level: a Mexico that is governed by a council of hundreds of indigenous people from all nations and tribes guided by the wisdom of their ancestors.

Central to the proposal is that the candidate who will represent the Indigenous Council of Government be an indigenous woman. Galeano, in his explanation, continually emphasized this point. He said that both mestizos (non-indigenous) and men have proved incapable of governance, and that this point was not up for debate. He also reminded us that this will not be a government run by any and all indigenous people, because there are of course indigenous landowners, paramilitary, and police, as well as indigenous communities that have been bought out by the government. It will be a CNI government, running not with a political platform, but rather a program of struggle that is explicitly anti-capitalist.

Galeano also emphasized that it must be the CNI that approves and constructs the campaign, not the EZLN. In 2006 the EZLN ran ‘the Other Campaign’ parallel to the presidential race to spread the word of autonomy and urge the people of Mexico to organize their communities outside of the electoral sphere. In his speech at the Fifth Congress, Galeano explained that in the Other Campaign, the EZLN led and the Indigenous Peoples of Mexico followed, and that it needed to be the other way around, with the Indigenous Peoples in resistance leading the nation.

The aim of the presidential campaign will be not only to win, but to fortify and unite the CNI and, as one delegate from Michoacán said, to “force the people of Mexico to turn and look at us”. In his opening speech, Subcommander Moisés repeated the urgency of uniting the people of the country and the city:

“Now is the time to remind the Ruler and his managers and overseers who it was who gave birth to this nation, who works the machines, who creates food from the earth, who constructs buildings, who paves the roads, who defends and reclaims the sciences and the arts, who imagines and struggles for a world so big that there is always a place to find food, shelter and hope.”

ANOTHER GOVERNMENT IS POSSIBLE

Some may question the possibility or efficiency of a collectively run indigenous government. The assembly itself refuted these doubts. Over 500 people from all different cultures and contexts discussed the proposal for three twelve-hour days without a single moment of disrespect. Instead of arguing based on ideology or political views, they truly listened to and, in the face of doubt, convinced one another. Most importantly, no delegate spoke from personal interest, but rather the collective interest of their community.

The consensus, then, that the proposal be brought back to their communities for consultation, was based on a true and complete agreement that the presidential campaign would benefit them all. Compared to the disrespect, corruption, corporate control, and political deadlock that we are used to in our current federal governments, the CNI was an example of the power of traditional governance.

This campaign will be unlike any other in the history of the world. In this moment of global political despair, particularly in the midst of the US presidential elections, the EZLN is once again challenging us to imagine outside of the defined realm of possibilities. After being denied a space in Mexico for over 500 years, they are deciding to construct a new Mexico and eventually, Galeano said, a new world.

In the words of the General Command of the EZLN:

Now is the hour of the National Indigenous Congress.

With its step, let the earth tremble at its core.

With its dreams, let cynicism and apathy be vanquished.

In its words, let those without voice be lifted up.

With its gaze, let darkness be illuminated.

In its ear, let the pain of those who think they are alone find a home.

In its heart, let desperation find comfort and hope.

In its challenge, let the world be seen anew.