by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 12, 2013 | Gender, Women & Radical Feminism

By Delilah Campbell

This article was originally published by Trouble & Strife, and is republished here with permission from the publisher.

For a couple of weeks in early 2013, it seemed as if you couldn’t open a newspaper, or your Facebook newsfeed, without encountering some new contribution to a war of words that pitted transgender activists and their supporters against allegedly ‘transphobic’ feminists.

It had started when the columnist Suzanne Moore wrote a piece that included a passing reference to ‘Brazilian transsexuals’. Moore began to receive abuse and threats on Twitter, which subsequently escalated to the point that she announced she was closing her account. Then Julie Burchill came to Moore’s defence with a column in the Sunday Observer newspaper, which attacked not only the Twitter trolls, but the trans community in general. Burchill’s contribution was intemperate in both its sentiments and its language—not exactly a surprise, since that’s essentially what editors go to her for. If what you want is balanced commentary on the issues of the day, you don’t commission Julie Burchill. Nevertheless, when the predictable deluge of protests arrived, the Observer decided to remove the piece from its website. The following week’s edition carried a lengthy apology for having published it in the first place. Senior staff, it promised, would be meeting representatives of the trans community for a full discussion of their concerns.

Liberal consensus

This was a notable climbdown by one of the bastions of British liberal journalism. Only a couple of weeks earlier, another such bastion, the Observer‘s sister-paper The Guardian, had published an opinion piece on ‘paedophilia’ (aka the sexual abuse of children), which argued for more understanding and less condemnation. In the wake of the Jimmy Savile affair that was certainly controversial, and plenty of readers found it offensive. But it wasn’t removed from the website, nor followed by a grovelling apology. Evidently it was put in the category of unpopular opinions which have a right to be aired on the principle that ‘comment is free’. But when it comes to offending trans people, it seems the same principle does not apply.

It’s not just the liberal press: a blogger who re-posted Burchill’s piece, along with examples of the abuse Suzanne Moore had received on Twitter, found she had been blocked from accessing her own blog by the overseers of the site that hosted it. Meanwhile, the radical feminist activist and journalist Julie Bindel, whose criticisms of trans take the form of political analysis rather than personal abuse, has for some time been ‘no platformed’ by the National Union of Students—in other words, banned from speaking at events the NUS sponsors, or which take place on its premises.

More generally, if you want to hold a women-only event from which trans women are excluded, you are likely to encounter the objection that this exclusion is illegal discrimination, and also that the analysis which motivates it—the idea that certain aspects of women’s experience or oppression are not shared by trans women—is itself an example of transphobia. Expressed in public, this analysis gets labelled ‘hate-speech’, which there is not only a right but a responsibility to censor.

The expression of sentiments deemed ‘transphobic’ has quickly come to be perceived as one of those ‘red lines’ that speakers and writers may not cross. It’s remarkable, when you think about it: if you ask yourself what other views either may not be expressed on pain of legal sanction, or else are so thoroughly disapproved of that they would rarely if ever be permitted a public airing (and certainly not an unopposed one), you come up with examples like incitement to racial hatred and Holocaust denial. How did it come to be the case that taking issue with trans activists’ analyses of their situation (as Julie Bindel has) or hurling playground insults at trans people (as Julie Burchill did) automatically puts the commentator concerned in the same category as a Nick Griffin or a David Irving?

Silencing their critics, often with the active support of institutions that would normally deplore such illiberal restrictions on free speech, is not the only remarkable achievement the trans activists have to their credit. It’s also remarkable how quickly and easily trans people were added to the list of groups who are legally protected against discrimination, and even more remarkable that what was written into equality law was their own principle of self-definition—if you identify as a man/woman then you are entitled to be recognized as a man/woman. In a very short time, this tiny and previously marginal minority has managed to make trans equality a high profile issue, and support for it part of the liberal consensus.

Here what interests me is not primarily the rights and wrongs of this: rather I want to try to understand it, to analyse the underlying conditions which have enabled trans activists’ arguments to gain so much attention and credibility. Because initially, to be frank, I found it hard to understand why the issue generated such strong feelings, and why feminists were letting themselves get so preoccupied with it. Both the content and the tone of the argument reminded me of the so-called ‘sex wars’ of the 1980s, when huge amounts of time and energy were expended debating the rights and wrongs of lesbian sadomasochism and butch/femme relationships. ‘Debating’ is a euphemism: we tore ourselves and each other apart. I don’t want to say that nothing was at stake, but I do think we lost the plot for a while by getting so exercised about it. The trans debate seemed like another case where the agenda was being set by a few very vocal individuals, and where consequently an issue of peripheral importance for most women was getting far more attention from feminists than it deserved.

But as I followed the events described at the beginning of this piece, and read some of the copious discussion that has circulated via social media, I came to the conclusion that what’s going on is not just a debate about trans. There is such a debate, but it’s part of a much larger and more fundamental argument about the nature and meaning of gender, which pits feminists (especially the radical variety) against all kinds of other cultural and political forces. Trans is part of this, but it isn’t the whole story, nor in my view is it the root cause. Actually, I’m inclined to think that the opposite is true: it is the more general shift in mainstream understandings of gender which explains the remarkable success of trans activism.

Turf wars

It is notable that the policing of what can or cannot be said about trans in public is almost invariably directed against women who speak from a feminist, and especially a radical feminist, perspective. It might be thought that trans people have far more powerful adversaries (like religious conservatives, the right-wing press and some members of the medical establishment), and also far more dangerous ones (whatever radical feminists may say about trans people, they aren’t usually a threat to their physical safety). And yet a significant proportion of all the political energy expended by or on behalf of trans activism is expended on opposing and harassing radical feminists.

This has led some commentators to see the conflict as yet another example of the in-fighting and sectarianism that has always afflicted progressive politics—a case of oppressed groups turning on each other when they should be uniting against their common enemy. But in this case I don’t think that’s the explanation. When trans activists identify feminists as the enemy, they are not just being illogical or petty. Some trans activists refer to their feminist opponents as TERFs, meaning ‘trans-exclusive radical feminists’, or ‘trans-exterminating radical feminists’. The epithet is unpleasant, but the acronym is apt: this is very much a turf dispute, with gender as the contested territory.

At its core, the trans struggle is a battle for legitimacy. What activists want to get accepted is not just the claim of trans people for recognition and civil rights, but the whole view of gender and gender oppression on which that claim is based. To win this battle, the trans activists must displace the view of gender and gender oppression which is currently accorded most legitimacy in progressive/liberal circles: the one put forward by feminists since the late 1960s.

Here it might be objected that feminists themselves don’t have a single account of gender. True, and that’s one reason why trans activists target certain feminist currents more consistently than others [1]. But in fact, the two propositions about gender which trans activists are most opposed to are not confined to radical feminism: both go back to what is often regarded as the founding text of all modern feminism, Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 classic The Second Sex, and they are still asserted, in some form or other, by almost everyone who claims any kind of feminist allegiance, be it radical, socialist or liberal. The first of these propositions is that gender as we know it is socially constructed rather than ‘natural’; the second is that gender relations are power relations, in which women are structurally unequal to men. On what exactly these statements mean and what they imply for feminist politics there is plenty of internal disagreement, but in themselves they have the status of core feminist beliefs. In the last 15 years, however, these propositions—especially the first one—have become the target of a sustained attack: a multi-pronged attempt to take the turf of gender back from feminism.

Trans activists are currently in the vanguard of this campaign, but they didn’t start the war. Some of its most important battles have been fought not in the arena of organized gender politics, but on the terrain of science, where opposition to feminism, or more exactly to feminist social constructionism, has been spearheaded by a new wave of biological essentialists. The scientists with the highest public profile, men like Stephen Pinker and Simon Baron-Cohen, are politically liberal rather than conservative, and claim to support gender equality and justice: what they oppose is any definition of those things based on the assumption that gender is a social construct. Their goal is to persuade their fellow-liberals that feminism got it wrong about gender, which is not socially constructed but ‘hard-wired’ in the human brain.

This attack on the first feminist proposition (‘gender is constructed’) leads to a reinterpretation of the second (‘gender relations are unequal power relations’). Liberals do not deny that women have suffered and may still suffer unjust treatment in male-dominated societies, but in their account difference takes precedence over power. What feminists denounce as sexism, and explain as the consequence of structural gender inequality, the new essentialists portray as just the inevitable consequence of natural sex-differences.

Meanwhile, in less liberal circles, we’ve seen the rise of a lobby which complains that men and boys are being damaged—miseducated, economically disadvantaged and marginalized within the family—by a society which has based its policies for the last 40 years on the feminist belief that gender is socially constructed: a belief, they say, which has now discredited by objective scientific evidence. (Some pertinent feminist criticisms of this so-called ‘objective’ science have been aired in T&S: see here for more discussion.)

Another relevant cultural trend is the neo-liberal propensity to equate power and freedom, in their political senses, with personal freedom of choice. Across the political spectrum, it has become commonplace to argue that what really ‘empowers’ people is being able to choose: the more choices we have, and the freer we are to make them, the more powerful we will be. Applied to gender, what this produces is ‘post-feminism’, an ideology which dispenses with the idea of collective politics and instead equates the liberation of women with the exercise of individual agency. The headline in which this argument was once satirized by The Onion—‘women now empowered by anything a woman does’—is not even a parody: this is the attitude which underpins all those statements to the effect that if women choose to be housewives or prostitutes, then who is anyone (read: feminists) to criticize them?

This view has had an impact on the way people understand the idea that gender is socially constructed. To say that something is ‘constructed’ can now be taken as more or less equivalent to saying that in the final analysis it is—or should be—a matter of individual choice. It follows that individuals should be free to choose their own gender identity, and have that choice respected by others. I’ve heard several young (non trans-identified) people make this argument when explaining why they feel so strongly about trans equality: choice to them is sacrosanct, often they see it as ‘what feminism is all about’, and they are genuinely bewildered by the idea that anyone other than a right-wing authoritarian might take issue with an individual’s own definition of who they are.

The gender in transgender

Current trans politics, like feminism, cannot be thought of as an internally unified movement whose members all make exactly the same arguments. But although there are some dissenting voices, in general the views of gender and gender oppression which trans activists promote are strongly marked by the two tendencies just described.

In the first place, the trans account puts little if any emphasis on gender as a power relation in which one group (women) is subordinated to/oppressed by the other (men). In the trans account, gender in the ‘men and women’ sense is primarily a matter of individual identity: individuals have a sovereign right to define their gender, and have it recognized by society, on the basis of who they feel themselves to be. But I said ‘gender in the men and women sense’ because in trans politics, gender is understood in another sense as well: there is an overarching division between ‘cisgendered’ individuals, who identify with the gender assigned to them at birth, and ‘transgendered’ individuals, who do not identify with their assigned gender. Even if trans activists recognize the feminist concept of male power and privilege, it is secondary in their thinking to ‘cis’ power and privilege: what is considered to be fundamentally oppressive is the devaluing or non-recognition of ‘trans’ identities in a society which systematically privileges the ‘cis’ majority. Opposition to this takes the form of demanding recognition for ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ as categories, and for the right of any trans person to be treated as a member of the gender group they wish to be identified with.

At this point, though, there is a divergence of views. Some versions of the argument are based on the kind of biological essentialism which I described earlier: the gender with which a person identifies—and thus their status as either ‘cis’ or ‘trans’—is taken to be determined at or before birth. The old story about transsexuals—that they are ‘women trapped in men’s bodies’, or vice-versa—has morphed into a newer version which draws on contemporary neuroscience to argue that everyone has a gendered brain (thanks to a combination of genes and hormonal influences) which may or may not be congruent with their sexed body. In ‘trans’ individuals there is a disconnect between the sex of the body and the gender of the brain.

In other versions we see the influence of the second trend, where the main issue is individual freedom of choice. In some cases this is allied to a sort of postmodernist social utopianism: trans is presented as a radical political gesture, subverting the binary gender system by cutting gender loose from what are usually taken to be its ‘natural’, biological moorings. This opens up the possibility of a society where there will be many genders rather than just two (though no one who makes this argument ever seems to explain why that would be preferable to a society with no genders at all). In other cases, though, choice is presented not as a tactic in some larger struggle to make a better world, but merely as an individual right. People must be allowed to define their own identities, and their definitions must be respected by everyone else. On Twitter recently, in an argument about whether someone with a penis (and no plans to have it removed) could reasonably claim to be a woman, a proponent of this approach suggested that if the person concerned claimed to be a woman than they were a woman by definition, and had an absolute right to be recognized as such. In response, someone else tweeted: ‘I’m a squirrel’. Less Judith Butler, more Alice Through the Looking Glass.

Proponents of the first, essentialist account are sometimes critical of those who make the second, and ironically their criticism is the same one I would make from a radical feminist perspective: this post-feminist understanding of social constructionism is trivializing and politically vacuous. What trans essentialists think feminists are saying when they say gender is socially constructed is that gender is nothing more than a superficial veneer. They reject this because it is at odds with their experience: it denies the reality of the alienation and discomfort which leads people to identify as trans. This is a reaction feminists ought to be able to understand, since it parallels our own response to the dismissal of issues like sexual harassment as trivial problems which we ought to be able to ‘get over’—we say that’s not how women experience it. But in this case it’s a reaction based on a misreading: for most feminists, ‘socially constructed’ does not imply ‘trivial and superficial’.

In the current of feminism T&S represents, which is radical and materialist, gender is theorized as a consequence of social oppression. Masculinity and femininity are produced through patriarchal social institutions (like marriage), practices (like the division of labour which makes women responsible for housework and childcare) and ideologies (like the idea of women being weak and emotional) which enable one gender to dominate and exploit the other. If these structures did not exist—if there were no gender—biological male/female differences would not be linked in the way they are now to identity and social status. The fact that they do continue to exist, however, and to be perceived by many or most people as ‘natural’ and immutable, is viewed by feminists (not only radical materialists but most feminists in the tradition of Beauvoir) as evidence that what is constructed is not only the external structures of society, but also the internalized feelings, desires and identities that individuals develop through their experience of living within those structures.

Radical feminists, then, would actually agree with the trans activists who say that gender is not just a superficial veneer which is easily stripped away. But they don’t agree that if something is ‘deep’ then it cannot be socially constructed, but must instead be attributed to innate biological characteristics. For feminists, the effects of lived social experience are not trivial, and you cannot transcend them by an individual act of will. Rather you have to change the nature of social experience through collective political action to change society.

The rainbow flag meets the double helix

When I first encountered trans politics, in the 1990s, it was dominated by people who, although their political goals differed from feminism’s, basically shared the feminist view that gender as we knew it was socially constructed, oppressive, and in need of change through collective action. This early version of trans politics was strongly allied with the queer activism of the time, emphasized its political subversiveness, and spoke in the language of queer theory and postmodernism. It still has some adherents today, but over time it has lost ground to the essentialist version that stresses the naturalness and timeless universality of the division between ‘trans’ and ‘cis’, and speaks in two other languages: on one hand, neurobabble (you can’t argue with the gender of my brain), and on the other, identity politics at their most neo-liberal (you can’t argue with my oppression, my account of my oppression, or the individual choices I make to deal with my oppression).

Once again, though, this development is not specific to trans politics. Trans activists are not the first group to have made the journey from radical social critique to essentialism and neoliberal individualism. It is a more general trend, seen not only in some ‘post-feminist’ campaigning by women, but also and perhaps most clearly in the recent history of gay and lesbian activism.

In the heyday of the Women’s and Gay Liberation Movements, the view was widely held that sexuality was socially constructed, and indeed relatively plastic: lesbianism, in particular, was presented by some feminists as a political choice. But in the last 20 years this view has largely withered away. Faced with well-organized opponents denouncing their perverted ‘lifestyle choices’, some prominent gay/lesbian activists and organizations began promoting the counter-argument that homosexuals are born, not made. Of course the ‘born that way’ argument had always had its supporters, but today it has hardened into an orthodoxy which you deviate from at your peril. Not long ago the actor Cynthia Nixon, who entered a lesbian relationship fairly late in life, made a comment in an interview which implied that she didn’t think she’d always been a lesbian. She took so much flak from those who thought she was letting the side down, she was forced to issue a ‘clarification’.

Since ‘born that way’ became the orthodox line, there has been more mainstream acceptance of and sympathy for the cause of gay/lesbian equality, as we’ve seen most recently in the success of campaigns for same-sex marriage. Though it is possible this shift in public attitudes would have happened anyway, it seems likely that the shift away from social constructionism helped, by making the demand for gay rights seem less of a political threat. The essentialist argument implies that the straight majority will always be both straight and in the majority, because that’s how nature has arranged things. No one need fear that granting rights to gay people will result in thousands of new ‘converts’ to their ‘lifestyle’: straight people won’t choose to be gay, just as gay people can’t choose to be straight.

If you adopt a social constructionist view of gender and sexuality, then lesbians, gay men and gender non-conformists are a challenge to the status quo: they represent the possibility that there are other ways for everyone to live their lives, and that society does not have to be organized around our current conceptions of what is ‘natural’ and ‘normal’. By contrast, if you make the essentialist argument that some people are just ‘born different’, then all gay men, lesbians or gender non-conformists represent is the more anodyne proposition that diversity should be respected. This message does not require ‘normal’ people to question who they are, or how society is structured. It just requires them to accept that what’s natural for them may not be natural for everyone. Die-hard bigots won’t be impressed with that argument, but for anyone vaguely liberal it is persuasive, appealing to basic principles of tolerance while reassuring the majority that support for minority rights will not impinge on their own prerogatives.

For radical feminists this will never be enough. Radical feminism aspires to be, well, radical. It wants to preserve the possibility that we can not only imagine but actually create a different, better, juster world. The attack on feminist social constructionism is ultimately an attack on that possibility. And when radical feminists take issue with trans activists, I think that is what we need to emphasize. What’s at stake isn’t just what certain individuals put on their birth certificates or whether they are welcome at certain conferences. The real issue is what we think gender politics is about: identity or power, personal choice or structural change, reshuffling the same old cards or radically changing the game.

[1] A more detailed discussion of feminist ideas about gender, which looks at their history and at what is or isn’t shared by different currents within feminism, can be found in Debbie Cameron and Joan Scanlon’s article ‘Talking about gender’.

From Trouble and Strife: http://www.troubleandstrife.org/new-articles/who-owns-gender/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 7, 2013 | Gender

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

What makes a radical a radical is a willingness to look honestly and critically at power; more specifically, imbalances of power. We ask: Why does one group have more power than another? Why can one group harm another with impunity? Why is one group free while another is not? These kinds of questions have long been used by radicals to identify oppression and take action against it. The process has seemed both straight-forward and effective—until applied to the oppression of women.

As persistently as the radical Left has put names to the many rotten manifestations of the dominant culture, they have ignored, downplayed, and denied the one called patriarchy. While it’s generally understood that racism equals terror for people of color, that heterosexism equals terror for lesbians and gay men, that colonialism equals terror for traditional and indigenous communities, that capitalism equals terror for the global poor, and that industrialism equals terror for the earth, radicals somehow just can’t get that patriarchy equals terror for women. If it ever comes up at all, the oppression of women is diluted to the point of sounding more like a bunch of isolated, temporary, uncomfortable circumstances than what it really is: an ongoing war against the freedom, equality, and human rights of more than half the world’s population.

The degree to which sexism, male privilege, and patriarchy are not addressed amongst radicals is the degree to which they plague us. It’s a vicious cycle: as men on the radical Left repress feminism, they forcibly silence concerns about unjust male power within the radical Left, and thus solidify dominance over political movements which will likely never again be able to overcome unjust male power.

Patriarchy run amok is the enemy of truly radical activism. There can be no liberation in the world, if those claiming to fight for it aren’t ready for the liberation of women in their own ranks. As my dear neighbor says, “There’s nothing progressive about treating women like dirt; that’s what’s happening already.”

Maybe some of these men don’t see their privilege. Or maybe they see it fine and feel entitled to it. In either case, most are comfortable with the status afforded to them based on their sex, both in society and social movements. Men sit atop a hierarchy with half of humanity beneath us, forcibly there for us to talk at, dump undesirable work on, and use for sex. This reality doesn’t simply disappear by calling yourself “radical.” Indeed, any radical who doesn’t see this—never mind challenge and stop it—isn’t worth the name.

Too often, so-called radical politics are really just men’s politics. Righteous declarations about resistance to all forms of domination aside, men cleverly manipulate movements to stifle anything threatening our own power and privilege—including women.

Within this rigged game, radical men and the political groups they control are more than happy to address patriarchy; as long as they control the debate, it’s no sweat. With a snap of the fingers, the fangs of feminism disappear. Men are oppressed too, they plea. Things aren’t as bad as they seem, we learn. Women are liberated, they demand. And somehow, with all traces of common sense thrown to the wind, the radical Left as a whole eats the lies and turns them into political policy.

If only radicals would understand gender like they do race and class. It seems so obvious: gender, like race and like class, is a social construct that justifies the oppression of one group by another. That’s it. But ask most—though, especially men—on the radical Left about gender, and prepare for the bizarre. In taking power entirely out of the equation, they claim gender is really just a spectrum to choose from, or something innate and therefore inevitable, or even a metaphorical and playful war between the sexes.

In actual reality, gender is none of these things. It’s not a choice; women don’t have the power to decide to not be treated as they will within a woman-hating culture. It’s not natural; biology is an excuse used to justify the ideology of patriarchy. It’s not fun and the war against women is not metaphor. Assault, slavery, exploitation, trafficking, and second-class status are daily fare for women, and gender is the excuse. You don’t accept or play with a hierarchy; you dismantle it. Radicals should know this.

Gender is a terrible lie with the realest of consequences. It starts with human beings and socializes—read: deforms—them into classes of people called “men” and “women”. Further, it claims that men and women each possess an innate set of personal habits—and worth—termed masculinity and femininity, or “maleness” and “femaleness”. Men learn domination and women learn submission. Patriarchy thrives.

This social construction is the same with race and class. The difference is that radicals would have no problem—we hope—seeing through the idea of some innate (or chosen) “blackness” or “poorness”. No human being is born on the bottom of a hierarchy; women, like the global poor and people of color, are forced there.

Power isn’t pulled from thin air; it is taken from the powerless. If men have power, women don’t.

Masculinity is defined by the violation of boundaries. No longer simply human, men use sheer military-style force to get what they want, to satisfy an insatiable ego. Men prove we are real men by making others—often women—bend, and ultimately break, to our wills.

Male privilege is the grand rationalization, the justification of unjust power that we men try to make ourselves, and everyone else, believe. The lesson is that masculinity is normal and men are absolved from accountability; that men know best and are always right. The hierarchy thus becomes inevitable, resistance seeming like an utter waste of time.

Feminism is the other side of the war. It is, in the brave words of Andrea Dworkin, “the political practice of fighting male supremacy in behalf of women as a class.” This commitment is radical politics at its most honest, which is precisely why the male-dominated radical Left stands in its way.

Feminism explodes the lies that make patriarchy seem benign. It demands full humanity for women and is willing to struggle to achieve it.

When we’re honest about the breadth of damage that gender does to women, we see the breadth of action necessary to get us from here to justice. Sexism is clearly not a mere uncomfortable circumstance, amendable by attitude alone. Rape, pornography, humiliation, trafficking, and reproductive slavery are anything but mental events. If the radical Left would look honestly at these atrocities—let alone, not participate in them—we’d know what to do: organize and resist.

Instead, radicals call it “sexual liberation” and choose to celebrate it—a heart-breaking legacy with its roots in patriarchy and history in the social movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. If a woman can choose to fuck, they claim, she must be free.

Choice, however, is only as meaningful as what there is to choose from. Women can choose between invisibility and sexual exploitation; they can choose between poverty and sexual exploitation; they can choose between death and sexual exploitation. I’d trust radicals to call bluff here if the opposite—collusion with the sexual exploitation of women—hadn’t been confirmed over and over again.

Feminism strikes a nerve. When men don’t get our way, backlash isn’t too far behind. Feminists face it from all directions. It seems anarchists, communists, sexual libertarians, men’s rights activists, and right-wingers can agree on at least one thing: the sanctity of male power. Men, along with whatever groups they dominate, come out in full force to put women back in place, whether through slander, censorship, threats, or physical violence.

There’s been little reason for women to count the male-dominated radical Left as anything resembling an ally. On the contrary, radicals seem ever willing to lend a hand to the other side. Take just this past week for example, when one environmentalist woman was barred from speaking at a university’s Earth Day event because she happened to also be a feminist; and when a decades-old women’s music festival was publicly ostracized for not letting men in; and when a venue slated to host one of the world’s only radical feminist conferences is considering reneging on the agreement after ongoing harassment from radical and conservative men, alike.

But if it’s not blunt retaliation men use to silence feminist women, its outright lies. The most common one is that men are, in fact, oppressed too. The radical Left has taken the bait. In the face of story after story depicting the terror waged daily against women, radicals want to know one thing: what about the men?

Of course men experience oppression—but not because we are men. Patriarchy means that, no matter the individual man, he will be treated as more of a human being than a woman would within the same circumstances. Men may be subjugated in a myriad of ways—each abhorrent and deserving of resistance in its own right—but not because we were born not female. Indeed, even the most otherwise oppressed or egalitarian or radical men have the capacity to use their power as men to hurt women. We needn’t ignore one injustice to see another.

If we, as radicals, are to live up to our name and traditions by getting to the roots of unjust power, we need to reject and combat patriarchy on all counts, at every level. Every time we allow men to wield power over women, we help the enemy.

If radical men want to fight the power, as many claim, we can start with men’s power over women. We can resist domination in all its manifestations; even—or especially—when doing so threatens our own privilege; even when it means changing who we are.

There’s no revolution and no justice without freedom for women. Patriarchy is destroying our social movements as surely as it’s destroying the lives of women and as surely as it’s destroying the planet. As musician Ani DiFranco sings, “The road to ruin is paved in patriarchy.” The road to revolution, on the other hand, is paved in feminism. As radicals, the choice is up to us: ruin or revolution?

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.

A Swedish translation of this article is available at: http://djupgron.wordpress.com/2013/05/12/den-sexistiska-radikala-vanstern-versus-kvinnor/

A French translation of this article is available at: http://coll.lib.antisexiste.free.fr/CLAS.html

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 1, 2013 | Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

Do you believe in a better world? Do you believe in one without the torture of poverty and slavery; without hierarchies based on dominance; without a dying planet? If you do believe in this world, what are you willing to do to help bring it about?

I know many who yearn for justice, but far fewer with any kind of plan for achieving it. There’s no lack of morality in this equation, just of strategy and, perhaps, courage.

Every movement for social change has understood that when a system of law is corrupt, we must turn instead to the laws of the universe: human rights, the living land, justice. These movements are always deemed radical—and that’s because they are. Hope and prayers do not alone work to change the world. We’re going to have to fight for it.

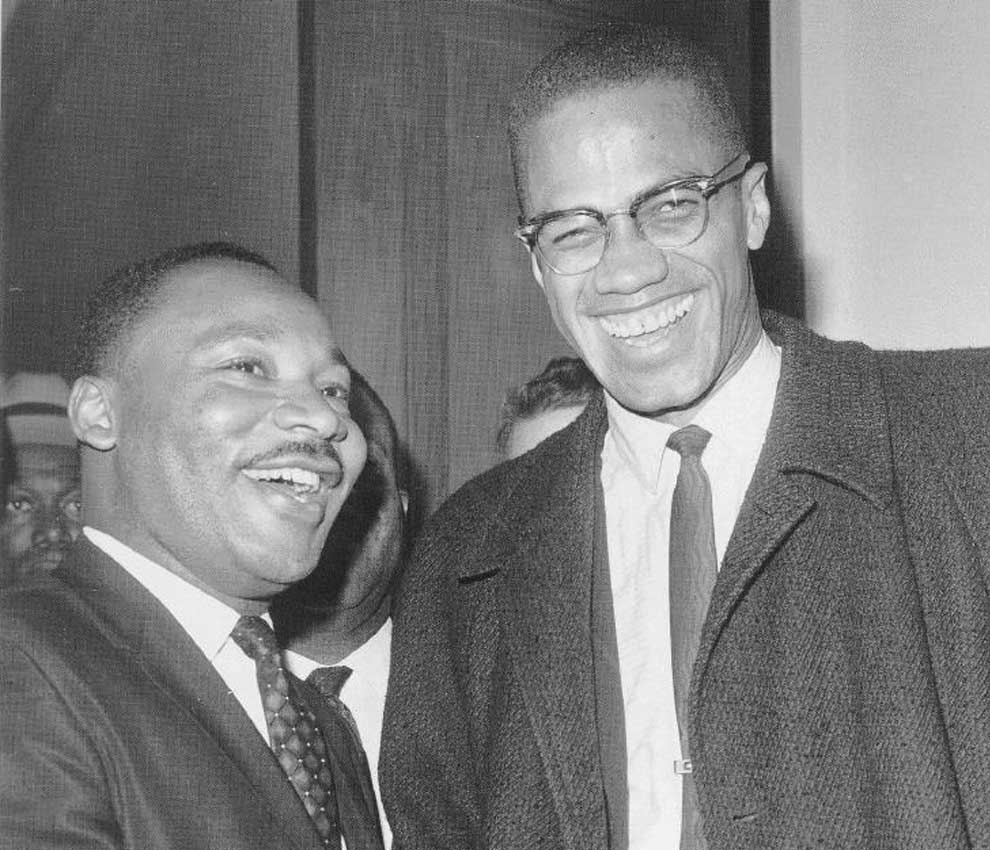

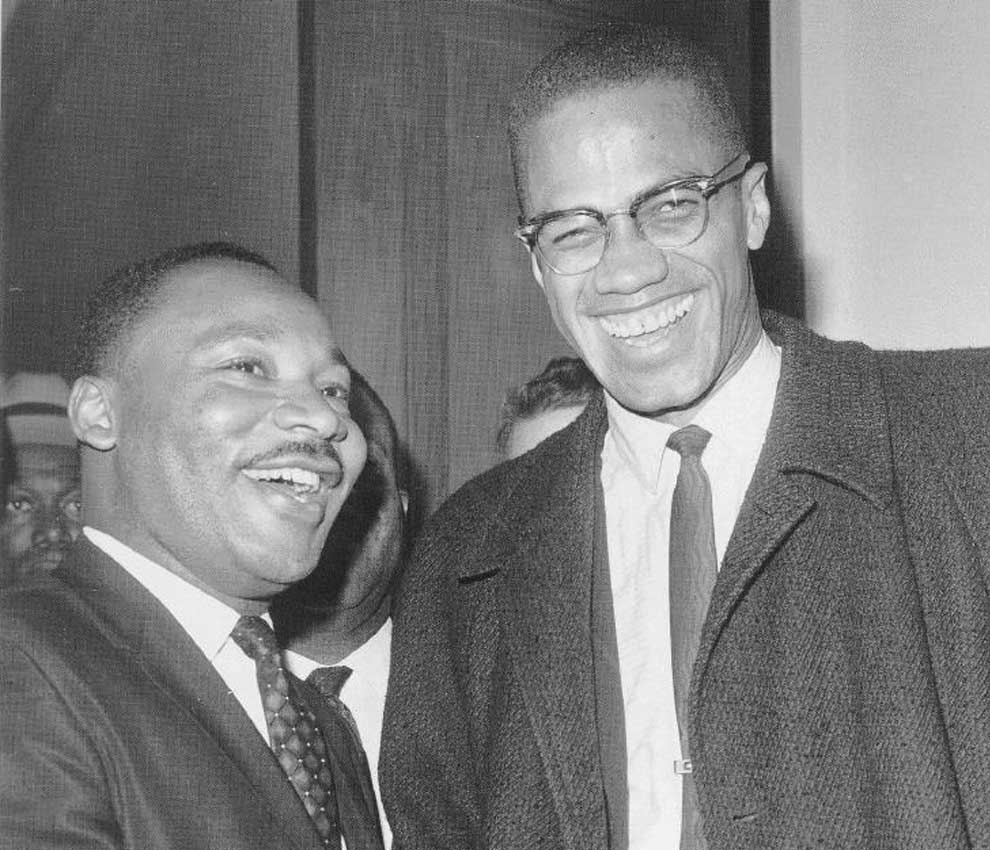

All your heroes of the past knew this. Those who won civil rights knew it. Those who won women’s suffrage knew it. Those who abolished slavery knew it. Those who freed India from colonial rule knew it.

Martin Luther King, Jr. clearly understood this. He said, “Freedom is never given to anybody, for the oppressor has you in domination because he plans to keep you there, and he never voluntarily gives it up. And that is where the strong resistance comes. We’ve got to keep on keeping on, in order to gain freedom. It is not done voluntarily, but it is done through the pressure that comes about from people who are oppressed. Privileged classes never give up their privileges without strong resistance.”

All movements striking at the roots of social problems were—and still are—radical by default.

There’s no shortage of issues that need tackling today. Pick your favorite atrocity: dying oceans, species extinction, deforestation, climate chaos, pollution, violence against women, militarism, white supremacy, poverty, colonialism, homophobia, slavery, government corruption. The hard reality is that the world and all that makes life worth living is under attack—and we’re losing the battle. Everything keeps getting worse and our standards for success keep getting lowered. Never has there been a more critical time for those who want a better world to rise and make it happen. So what’s stopping us?

Of course there are vast and powerful entities wholly invested in and mercilessly guarding the way things are. This is an old story; we’re Margaret Mead’s small group of thoughtful, committed citizens taking on a giant. But in reality, we’re not even there yet. No, we’re still struggling to find unity amongst ourselves, to gather the people necessary to begin making any change at all.

It’s long past time to be forthright about what divides us as activists. Most all of us want to see the same outcome—a living planet, flourishing human communities—but we stumble on how to get there. Sure, some things we just won’t agree on, and that’s perfectly fine. But with the stakes so high, are we willing to forfeit all possibility of effectiveness because we can’t find a way to get along?

Let’s talk about our differences so we can better find our common ground. Writer Lierre Keith has investigated the history of social movements and emerged with much of the work done for us. She suggests there are two major currents amongst activists: liberals and radicals. This is not a dichotomy: like reform and revolution, both liberals and radicals have been necessary and complimentary to each other. The key is balance and respect for various approaches to the same problems.

The first difference between radicals and liberals is how we view individuals. Radicals see society as made of groups or classes; individual people share common clause based on shared circumstances and goals. Liberals, on the other hand, see individuals as just that; each person is distinct from another. The “working class”, for example, was a radical concept which liberals have largely removed from their discourse.

Next is how social change happens. Liberals lend their energy to ideals and attitudes, certain that change will come one heart and mind at a time. Institutions are the targets of radicals, though, with old corrupt ones sought to be dismantled and replaced with just, sustainable, new ones. If Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement would have focused solely on convincing whites that blacks aren’t inferior, they would have been taking the liberal route. If they would have focused solely on defeating racist laws, they would have been taking the radical route. History suggests that it was both that got the job done.

A final difference centers on justice and what we think it looks like. Radicals tend to measure justice by long-term material conditions—a lack of oppression and destruction in everyday life, now and forever. Morality is predetermined for the liberals, with the law or broader society acting as judge. Any win in the realm of free speech, for example, might look like a step in the right direction to the liberal perspective, whereas radicals might be more concerned with eliminating hate speech (and groups), whether or not it is legally permissible.

Despite the distinctions, effective activism hinges on understanding power and how it works. Wherever we may fall on the spectrum, we must keep our eyes on power: who has it, how it’s being used, and how it can be transferred from the hands of the powerful to the hands of the powerless. There is no way to talk about social change without talking about power.

Again, all throughout history liberals and radicals have employed complimentary strategies to make tangible differences in the world. We may feel uncomfortable working with each other, but it’s either that or an increasingly ruined world. The ethical choice should be clear.

What liberals need to understand is that any efforts challenging systems of power are and will be seen as radical. There’s just no way around it and forging distance from radical counterparts is not only useless, but a betrayal of freedom-fighters before us. We need to remember that Rosa Parks’ hero was Malcolm X. We need to remember that Gandhi was successful because he was easier to negotiate with than Bhagat Singh’s militants. Neutrality is complicity and it’s time to take sides: one hand is the small group of capitalist monsters profiting off of misery and on the other is anyone willing to resist injustice.

Recently, I had a conversation with a member of the Democratic Party which highlights how far from solidarity many liberals have strayed. Upon meeting, he asked what I did. “I’m a writer,” I said. About what, he wondered? “Radical social change,” I told him. And the next fifteen minutes, up until the point I politely left, saw him adamantly discouraging me from using such a confrontational and extremist term as “radical.” My claims that this desperate time calls for radical responses fell on deaf ears, because how desperate can anything be with a Democrat in the White House? In hindsight, I wish I would’ve reminded him just how radical the movements have been that are now allowing for black, female, and homosexual candidates from his Party to get in office.

What radicals need to understand is that what is most militant is not always what is right, both in terms of strategy and morality. And sometimes it is. Power only changes by force, but force can take many different forms. Suffragists lobbied and campaigned for women to get the vote, but when that wasn’t working, they added sabotage to their arsenal. Simultaneously used, their tactics proved part of an ultimately successful strategy. Both approaches were radical because they applied force, but they were employed in very specific times and contexts. Strategy allows us to choose between tactics with a lens of pragmatism rather than by whim of emotion. Whatever actions are taken, they must be well thought out and conducted with discipline.

Too many radicals today fall into the trap of black-and-white thinking. They see bad institutions and therefore all institutions are bad. They see useless reforms and therefore all reforms are useless. They see poor leadership, and therefore no leadership is better.

Radical or liberal, we really need it all. We need the community organizers, the gardeners, the healers, the warriors, and the artists. Most of all, we need to each other’s work as necessary pieces of the larger struggle.

Regardless of our route, activists need to always remember the world we’re working towards. Solutions will come only after we honestly name the problems. This means we cannot look away from the severity of the situation, even if it doesn’t make us feel good. Social change is about social change and not about any individual’s emotional state. Suffering is real and it beckons us to fashion adequate responses.

Changing the world means naming the one we’re presently stuck with. It’s time to say this out loud: the problems we face are systemic, not random; they are symptoms of a social and economic arrangement of power. I call that arrangement industrial capitalism. You may call it what you like. What’s important is that we all understand that there is no future in the way things are.

Liberals, radicals, and anyone working towards a more just and sustainable world cannot continue to spend so much time condemning each other’s approaches. There’s a name for this destructive tendency: horizontal hostility. And unless we want to in-fight to the end of the world, it has to stop.

Success will be the forging of a culture of resistance strong and vibrant enough to take apart this society and build a new one. This means vast networks of communities of people supporting each other’s efforts towards a common goal. It means the artists support the warriors who support the healers who support the gardeners who support the community organizers who support the warriors. Not all in a culture of resistance need agree on everything; we just need to pledge that we won’t turn on our own in the heat of the struggle.

For every year, every day, and every moment we don’t act strategically and decisively, another person of color is terrorized by white police officers, another woman is violated by men, another indigenous culture is stamped out, another species is added to the extinction list, the health of human community and the entire planet accelerates in decline.

Those with fire and love in their hearts, those who live by moral obligation, know that the time to act is now. So the question becomes: will you join us in finally and totally changing this world. Is your privilege and comfort more important than justice, or will you join us? Are your ideals more important than the hard truth, or will you join us?

If you want a better world, what are you waiting for? Find your allies, work out your differences, and get down to business.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 17, 2013 | Alienation & Mental Health, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

By Joshua Headley / Deep Green Resistance New York

As a socially conscious person situated within the heart of global industrial civilization, I often experience, directly and indirectly, injustices on a daily basis.

A week ago, the NYPD (via two plainclothes officers) murdered a 16-year-old boy, Kimani Gray, firing 11 shots – hitting him 7 times in total; 3 in the back, 4 in the front. Monday night a large crowd began a vigil that would kick-off a week full of protest in the neighborhood – the night culminated in trash being thrown into the streets to slow down the riot police, glass bottles being thrown at officers from rooftop buildings, and the NYPD entering numerous apartments without warrants. Following that night (and for every day since) the East Flatbush neighborhood has been under military-style occupation with no less than three riot police on every single corner for more than 30 blocks. By Wednesday, the NYPD had declared the neighborhood a “Frozen Zone,” essentially affirming martial law by limiting press access and arresting anyone who did not precisely follow police instructions. One week later, tensions are still as high as ever, and justice has yet to be served.

This is just one example of many injustices that occur in this city every single day. The NYPD “Stop and Frisk” policy continues to racially profile men and women of color, funneling the youth of Harlem, the Bronx, and Brooklyn through the education-prison pipeline at alarming rates. “Crime” is on a steady rise, not as unsurprising as one may think due to the directly proportional rise in poverty among every borough and neighborhood in the city. Every day, more people lose their jobs, their access to food stamps and medical benefits, and every day more people lose hope for the future. In the last year alone, the city has seen multiple seemingly-random outbursts of violence– one man went borough to borough opening fire and stabbing pedestrians on the street at will; another opened fire near the Empire State Building after losing his job (while the NYPD themselves, in their attempt to “bring him down,” shot up to eight passerbys in their own cross-fire); and even a few people were, for unknown reasons, pushed in front of oncoming subway trains by complete strangers.

Subconsciously (and for some of us, consciously) we all know things are bad. Really bad. We don’t really need the mainstream media’s live Twitter feed to remind us of the state of decay in which our society functions. But often we ignore it – we do our best to keep our ear buds blasting noise and our eyes focused on the concrete to avoid any confrontation with reality. We say to ourselves, “I am a moral person, and I am responsible – I would never do such things and it’s really just a matter of educating and elevating others to my consciousness. If I lead by example, others will follow.” While one could (very easily) argue that this culture makes most of us, in fact, insane (or increasingly drives us to points of insanity), it still does take extraordinary leaps and bounds to get to a point in which we lose our morality and social responsibility entirely. I certainly know way too many socialists and activists who consider themselves to be The Most Moral and Just Citizens of the World™.

But, if that is generally true– if most leftists and activists do represent a moral high ground in our society, and our collective will for more social responsibility alone could alleviate the continually degrading human condition– why hasn’t it happened yet? Why haven’t those in power been persuaded to our side? Is this ultimately possible? Is it really just a matter of switching out the psychopaths that run our culture for more moral and responsible people? Will this result in the utopia of utopia’s in which all human needs are addressed and efficiently met thus eliminating all suffering? If not– if it really isn’t this simple – why do we waste so much time discussing it, and why haven’t our analyses and strategies changed?

Moral suasion as an argument and tool for social change is a bankrupt strategy. It not only falls short in the context of our current reality, it eventually becomes a counterrevolutionary force. Effective moral suasion is dependent upon the size of the oppressor(s). It generally does not work when applied to mass groups of people, and is generally only successful on a case-by-case basis with individuals and small groups. These individuals also have to be human beings, for the sole reason that to be persuaded they must have a conscience and/or an already existing morality (although it is pretty unlikely that an oppressor could ever have a conscience).

The reason, then, that moral argument is a bankrupt strategy for social change is because we are not dealing with individuals, small groups, or even solely human beings. What we currently face are arrangements of power through abstract systems and institutions of power (multinational corporations, nation-states, civilization, patriarchy, etc.) that involve large numbers of people that can be, and easily are, replaced. Our problems are systemic and no matter whom we “elect,” or choose to act on our behalf or for the greater good of humanity, the destructive nature of the system itself will continue unabated– acknowledging this is crucial to a radical analysis and a functional understanding of root causes of problems.

Many on the left, while acknowledging the various systemic problems in our society, do genuinely believe that if we switched to a more responsible, more moral society not based on greed or capitalism, that we will finally have the motive and incentive to create a sustainable and just future. The main oppositional force that prevents this change, so goes the argument, is capitalism – a highly inefficient economic system that funnels money, resources and power from the poor to the rich. It is therefore understood that it is capitalism’s social relations that create its inefficiency, and the hierarchy of its power prevents equitable distribution of its goods and services.

“We currently produce enough food to feed the entire world and yet millions of people die of starvation every year. If we change the social relations, and develop our personal capacities for mutual aid, we can feed every single human on this planet – no one would ever die of starvation.” Or so we are persuaded to believe. Sure, we can point to statistics of how much food is thrown out and wasted (in the United States alone, even) and logically come to a conclusion that this is a problem of distribution and efficiency.

Unfortunately, this type of logic fails to address the inherent “nature” of agriculture, industrialism, and civilization itself, which are all subject to (collectively and separately) diminishing returns and collapse. Ironically, these socialists, in their failure to question the given existence of these other systems, end up re-enforcing and defending the very processes they purport to oppose – a rather classic case of “revolutionaries” acting as their own counterrevolutionary force.

If this is the case, then here are some rather obvious questions we should ask ourselves: can industrial civilization and capitalism exist exclusively? Can we have a global industrial infrastructure functioning under socialism (even solely in a transitional phase), and still have a sustainable and moral society? Can we have our cake, and can we eat it, too? The answer: No. This isn’t only a fantasy – it is a seriously dangerous one.

For perhaps one could argue that certainly, under socialism, society would be more moral and ethical than how it currently exists under capitalism. But having a more moral society does not ultimately result in sustainability. These are two distinct (although highly interconnected) ideals. If our wish is to create both a fundamentally sustainable society and a fundamentally just and moral society, then we can’t forgive one for the sake of the other, and we have to start asking more radical questions about what this all might mean.

If there is one thing we understand about civilizations other than their rise and dominance in the last 10,000 years, it is that they are all fundamentally marked by collapse and degradation. Some last for thousands of years, some for centuries, but some (regrettably for us) barely make it past one or two centuries. The unifying processes here are the rise of cities, dense concentrations of population, the overshooting of carrying capacity, the limits to growth and the point of diminishing returns, and collapse (social, political, economic, and ecological).

Industrial civilization (i.e. urbanization, industrialism, industrial capitalism, etc.) is a specific arrangement of civilization characterized by massive urban centers and their dependency on machines and fossil fuel use. In its extremely short existence, just under two hundred years, we have seen an alarming rate of growth resulting in the hyper-interconnected global civilization of seven billion people in which we live today. The Population Reference Bureau describes this urbanization as such:

In 1800, only 3 percent of the world’s population [estimated in total at 1 billion people] lived in urban areas. By 1900, almost 14 percent were urbanites, although only 12 cities had 1 million or more inhabitants. In 1950, 30 percent of the world’s population resided in urban centers. The number of cities with over 1 million people had grown to 83.

“The world has experienced unprecedented urban growth in recent decades. In 2008, for the first time, the world’s population was evenly split between urban and rural areas. There were more than 400 cities over 1 million and 19 over 10 million. More developed nations were about 74 percent urban, while 44 percent of residents of less developed countries lived in urban areas. [1]

Megacities, as defined as urban centers with populations greater than 10 million people, have drastically increased – “just three cities had populations of 10 million or more in 1975, one of them in a less developed country. Megacities numbered 16 in 2000. By 2025, 27 megacities will exist, 21 in less developed countries.” This process of massive urbanization –unprecedented in size and scope – was made possible because of fossil fuel use, most specifically the “cheap” and “efficient” extraction of oil.

Because civilizations, in their inherent drive to greater and greater complexity, will inevitably reach a point of diminishing returns (i.e. when the amount that is returned per investment begins to decrease), they are subject to and defined by collapse. If the dramatic rise in human population was made possible because of fossil fuels (finite resources), it becomes crucial to question and understand when our civilization will reach the point of diminishing returns (peak energy).

The implications of reaching peak energy is a rapid decline in human population, a decline that will return world population to at least (if not less) the levels seen before the beginning of industrialism (a loss marked by billions). This process will occur whether or not peak energy is reached under capitalism or socialism, or a moral or immoral society. This is predominantly a structural problem – a problem in the way in which humans live on their landbase (a kind of social relation we often forget even exists).

As we can already see, based on our current dependency on energy intensive fossil fuel extraction (ex. Alberta tar sands oil) – at the same time of escalating erosion of soils, pollution of freshwaters, a rapid loss of biodiversity, and accelerating rates of biosphere pollution via emission of greenhouse gases – it should be a given that not only are we already past the point of diminishing returns but that the rate of collapse itself is accelerating.

Today, our current crisis is global and total in scope – our entire way of life and every living being (human and nonhuman) is hanging by a thread. Each day that passes, 200 more species go extinct, furthering a rapid loss of biodiversity. Each day, that thread gets thinner and the stress becomes even more unfathomable.

Current CO2 emissions are at 395 ppm – a level not reached in more than 15 million years. The time lag between levels of CO2 and temperature rise is roughly 30 years. Based on current levels of CO2 today alone, we are already locked into a global temperature increase of 3-6C over the next 30 years. An increase of 1.5C is all that is required to reach critical tipping points in which runaway global warming will occur, culminating in an abrupt extinction of nearly all biological life.

Each day, every single day industrial civilization marches on, the responsibility of action gets greater – but are we doing anything more than making sure we remain morally pure? Are we adequately escalating our actions to the severity of the problem?

There is nothing redeemable about this culture. Structurally, it is morally reprehensible – it requires massive amounts of violence (via conquest, genocide, slavery, repression, etc.) in order to “effectively” function and exist. There is nothing moral in having to steal resources from another group or landbase because your way of life is based on expansion rates that require more and more resources (from more and more places).

As has been said many times by others, the goal of an activist is not to try to navigate this culture and its systems of oppression with as much integrity as possible – the goal of an activist is to dismantle those systems. If we have a responsibility, as activists, to dismantle all systems of oppression and have a healthy, thriving planet for humans and nonhumans alike, we have to start talking more seriously (and radically) about where our problems come from and how to challenge them. This requires across the board questioning of everything we consider to be our “reality,” even when those questions get increasingly tough and hard to confront.

Where we go from here (and what we ultimately leave for future generations) is entirely up to us. If we are looking to be successful, the first step is (for once and for all) to throw away all of our bankrupt strategies and tactics. Our morality alone will not guarantee future generations will have air to breathe or water to drink. Throwing out one economic system for another, but not also taking with it its entire industrial infrastructure, will not stop the ecological degradation in any meaningful capacity.

Our time frame for effective action is rapidly shrinking and the longer we wait, the more destructive, chaotic, and total the collapse will be. If we have any expectation at all in not just surviving, but also repairing and restoring a thriving planet, we have to adapt a strategy that matches the severity of the problem. This culture must be stopped. We must dismantle industrial infrastructure, unlearn all destructive ideologies, and begin rebuilding genuinely sustainable communities as soon as possible, and by any means necessary.

[1] Human Population: Urbanization – Population Reference Bureau

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 6, 2013 | Direct Action, Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

Environmentalists today have our work cut out for us. Caught between the urgency of the ecological crises and reactionary capitalist forces that continue to push (quite successfully) for ever more outrageous and egregious destruction, finding an effective and timely path forward is no easy task. There are a wide variety of strategies for change vying for our attention, broadcast to us by a diversity of folks with a diversity of motivations—some of which are mixed, others confused, and more that are dangerous. By and large, the strategies we’ve adopted for our movements go unchallenged and unquestioned.

But given where we find ourselves—in the middle of an irredeemably exploitative and cruel society fundamentally dependent on fossil fuels—and what we’ve been able to accomplish so far in the fifty-some years of the environmental movement, it’s time to stop a moment and reflect.

What we’ve tried so far—everything from alternative consumer choices, lobbying, and symbolic protests to education, and localized permaculture lifeboats—has proven incapable of addressing the scale and severity of the crises at hand and ineffective in forcing change. While these tactics can be used to achieve certain goals, and certainly have their place within a serious movement for justice and sustainability, they will never be enough to accomplish what we must in the end.

So with that in mind, the time has come to have serious conversations and ask ourselves serious questions. What do we want to achieve, and how can we best achieve it?

Do we want to perpetuate a way of life that affords some of us with incredible material prosperity? Are we merely looking for new ways to sustain the unsustainable? Or do we want first and foremost to stop the destruction and exploitation of the living world, and are we prepared to adjust our society—our way of life—to what that requires of us? Are we prepared to see and name that destruction for what it is,industrial civilization, and do what’s necessary to bring a halt to it?

If so, are we willing to face what’s necessary to be successful? Are we willing to work for that goal by any means necessary, including sabotage and property destruction? Will we support those who do? For if the ends don’t justify the means, what does?

Are we willing to set the health of Earth as the ultimate metric by which we will be judged? As many others have said, those who come after us will not be swayed or moved by how deeply we ached at the world dying around us. They won’t forgive us no matter how big our marches and rallies were, nor how clever our slogans and chants. The precise harmony and abundance of our permaculture gardens will be irrelevant to them if the forests, rivers, and fish are gone. The spiritual fulfillment and inner peace we’ve found we be meaningless and resented if all the mountains have been ripped inside out, the air and water filled with poisons.

Fighting the good fight may satisfy us emotionally, but are we more concerned with emotional fulfillment or the health of the planet?

Either we win, and permanently put an end to this cancerous way of life—in no uncertain terms, dismantle industrial civilization—or it’s game over; baked topsoil devoid of bacteria and oceans empty of even plankton.

As all the tried and tired strategies, the benign, begging and ineffectual hopes for change fail repeatedly, are we prepared to take a new path? Are we willing, as a movement, to revisit our long-sworn oaths against direct action, sabotage, and property destruction? Are we left any other choice?

This is not an exhortation to action, not a dictate on what our tactics can or should be. And it’s certainly not an effort to incite you into doing anything you aren’t comfortable doing. This is an attempt to open the conversation, to humbly consider different strategies and tactics. Because what we’ve been doing so far isn’t working.

On the contrary, as a whole, the environmental movement is playing directly into the hands of the established systems of power. The solutions put forward by the mainstream fail to challenge industrialism, capitalism or civilization, and the mostly center around consumerism and economic growth—whether or not the planet survives is a moot point and is confined to the realm of rhetoric. The tactics proffered and peddled to us pre-packaged in marketing glitz and glamour will never be enough to carry us to our goals, because they refuse to confront and dismantle the material systems that are waging a relentless war against life. Instead, we plead with those in power, hoping in vain that they’ll change their hearts and minds.

But it is material systems—physical infrastructure of extraction and production—that are doing the deforesting, the strip mining, the fracking, the polluting, damming, the trawling; it’s not a few bad apples or an “unsustainable consciousness.” We can change hearts and minds until the sun burns out, but if we don’t confront and dismantle the structures of power that necessitates the devastation wreaked upon Earth by this culture, those compassionate hearts and minds will be irrelevant and quickly replaced by those better fitting the demands of the dominant power systems.

One measure of insanity is to do the same thing over and over and to expect different results. It’s long past time to admit that things aren’t changing; in the last 30 years, there hasn’t been a single peer-reviewed study that showed a living community that was improving or stable.

A recent study found that it’s twenty times more likely that climate change will be more extreme than forecasted than less extreme. Clearly what we’ve been doing isn’t working, or things would be getting better instead of worse (and the rate at which they’re getting worse is accelerating).

So where does that leave us? If the safe and fun strategies—the non-controversial and the convenient; the “green tech,” the lobbying, the consumer lifestyle choices—don’t work, what do we do? If we know it’s not working, how can we continue along the same path and expect anything different?

With so much—everything—at stake, will we collectively step over the line of comfort and safety that is afforded to us in exchange for our compliance and use whatever means necessary to stop the literal dismemberment of the planet’s life-support systems? If not us personally, will we support those who do?

When we look back in history we find countless examples of past movements facing near identical questions, and all too often they came to the decision that the use of physical force was necessary for fundamental change.

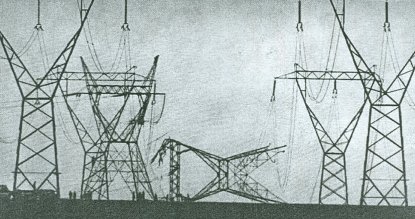

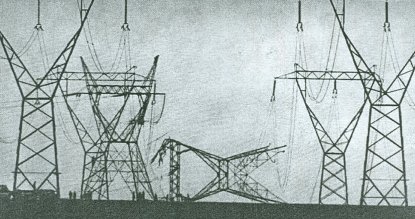

From the women’s suffrage movement which used arson against politicians who opposed the woman’s right to vote, to labor movements in the coal fields of Appalachia where miners battled company thugs. From the Black liberation struggles’ unabashed armed self-defense, to indigenous sovereignty struggles which employed militant land reclamations. From the ANC in South Africa and EOKA in Cyprus sabotaging electric transmission lines, to resistance forces across Europe during WWII attacking rail and transport infrastructures, and liberation movements around the world since using whatever means necessary to fight against colonialism. Strategic sabotage and other forms of militant action are proven to possess incredible potential for social movements to materially undermine the foundations of abusive power.

What will we do with that knowledge? How long will it take to decide, remembering that with every setting of the sun, another 200 species disappear from the world forever? Aren’t we overdue to have these conversations, to stop and ask these questions?

There isn’t any more time to be lost; we have lots of potential tools—tactics and strategies—available to us, and we need to put them all on the table, rather than limiting ourselves to least controversial (and least effective) among them. We need to accept the use of militant tactics, and support those who do. Strategic sabotage against industrial infrastructure has been used by countless movements to fight exploitation, and is undeniably effective.

When nothing else is succeeding in stopping the physical destruction of industrial society, can we finally accept militant action in defense of Earth as a viable option? With what’s at stake, can we afford not to?

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org