by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 3, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health

by Jim Tull / Local Futures

I recall a Buddhist parable involving a stick that appears from a distance to be a snake, causing fear to rise in the perceiver. As the perception shifts upon closer examination, the fear subsides and the relieved hiker continues down the path. Understanding and awareness have a lot to do with how we feel and how we act. As hosts to the dominant cultural mindset (our collective understanding of who we are in the universe), our minds play a critical part in both perpetuating our dominant way of life and also in shifting away from it. And so it’s just possible that I have performed no greater service in my three decades of activism than to simply challenge myself and others to consider the possibility that the social systems that support us and we sustain are inherently incapable of meeting basic human needs and that we must make a fresh start, in a sense, if we are to survive this century and prosper thereafter.

These systems are the largely invisible, cyclical patterns of interaction among and within society’s individuals, institutions and principalities. They include small town school systems all the way out to our globalized economic system and to the mother of them all, our globalized monoculture. You need to perceive the stick as a stick before you can confidently move on, and this consideration is a critical step in transforming the way we live. When an alcoholic decides to sober up, he needs to understand, as AA puts it, that he is powerless to the substance. This understanding is a necessary condition for recovery. Likewise, about 7 billion humans living on our planet are powerless to make our global systems support equitable, sustainable, enjoyable living. Further, we are powerless to use the tools of these systems to prevent our world from crashing down on itself.

In a few critical ways, our global monoculture dates back to the Mesopotamian settlements our history texts associate with the Agricultural Revolution. Over the millennia, this rapidly expanding cultural system, under the guise of various imperial masks, has come to produce predictable results, terrible and also quite marvelous. The terrible includes unrelieved poverty for the majority of the world’s population, widespread unhappiness and spiritual alienation, even (especially?) among the wealthy 10 percent of the world’s population, and the unsustainable use of natural resources. This last result seals our present day ultimatum – our culture and our survival as a species have become incompatible. As if possessing a will and mind of its own, the culture has a voracious appetite for assimilating all cultures into itself and then separating every thing under its umbrella from every other thing into the smallest possible units, mainly to compete with each other. Its compulsion is to consume and waste, grow and expand, dominate, control and compete at a speed and intensity that is destroying the societies we assume it has evolved to serve.

The systemic template of our civilization’s form of social organization is a domination or hierarchical model, in contrast to the tribal or partnership system, which is still fully operative among isolated tribal people and recessively, in remnant forms, throughout our society. Our institutions, even small ones, are virtually all hierarchical – power, wealth and status are concentrated in individuals occupying the higher positions of a pyramidal organizational structure. In contrast, a group of friends arranging for a day together at the park is more likely to organize itself and otherwise behave in a tribal or partnership fashion. Some nuclear and even extended families exhibit partnership qualities, as do cooperatives and collectives.

Despite the predictability of what is, in other ways, a very chaotic and patchwork culture, social innovators, entrepreneurs and activists continue even in this late and desperate hour to put their best energy into trying to make this system work. Though stepping from our prevailing way of life to a better one must be done in fact and not simply in our minds, I sense that we are forestalling the necessary leap in part because too many of us remain not only actively invested in the prevailing way, but mentally invested as well. And there are lots of folks who at some level perceive that things have deeply soured in our world but who, like the townspeople adoring their naked emperor, keep this outlook and associated anxiety well guarded, and carry on. Indeed, though the system as a whole is failing, individuals in society are rewarded with survival goods for maximizing their effectiveness within the system. And just as our collective faith holds up the currency and the economy it serves, our collective faith is also what ultimately keeps civilization itself, and its supporting culture, afloat. Our active cooperation with the systems and structures of the culture is an expression of this faith.

Though I press myself into the service of partnership community building as an alternative to this, I also express through my actions a reluctant allegiance to the big culture and systems upon which my survival depends. Yet as I personally go about my daily business in life, I carry with me some fluidly changing version of the following reminders to help reorient my thinking:

- Release your faith, Jim, in the capacity of our dominant culture, its systems and tools, to save us from social oppression, economic collapse and biological extinction. Though some of its tools (solar panels?) may be employed in the cultural hereafter, they are useful only in a marginal way in the current cultural context. Culture, as a function of how people think, understand and see the world, is the locus or hinge of social change. It is, for example, the source and determinant of technology. Promising and threatening technological advances (and potential advances) in bioengineering, fuel cells, etc., are very important, but secondary, concerns. “Keep your eyes on the prize” of cultural shift.

- Our culture, however it serves us, is now collapsing. I can’t imagine that any anthropologically trained space visitor would conclude otherwise. With each passing day, a newborn child stands less of a chance than a child born the day before of absorbing, internalizing and embracing what the grownups need to pass on to them to assure the culture’s survival. Teenagers and other adults are anxious and dis-eased. I assume that the rate of demise is of an exponential magnitude and that we’re now in the ‘moving very, very fast’ stage. We are also destroying the habitat our biological lives depend on at a similar rate. This is a collapse on two (related) fronts.

- Practice seeing the world as it is, in its genuine meaning, as interpreted by your most honest wits. Process attendant pain with others. Pay particular attention – honest attention – to young children. Resist writing off absurdities and horrors as normal, as business-as-usual, as just-the-way-the-world-is, as in ‘toddlers/teens just behave that way’. Allow yourself to witness and feel the effects of a desperate and dying culture.

- It may be possible to stop or even prevent a war, move more poor people into affordable housing or to make a nonpolluting car. Efforts like these are necessary. Keep making them, but also keep in mind that while they cushion systemic blows and enhance the lives of individuals (perhaps millions of them), these measures will not directly alter our cultural or systemic trajectories. If you teach a child to read in school, or campaign for school reform or more public expenditures for the school system, keep a third eye as you go on a not too distant future in which children, as fully reintegrated members of their communities, learn, grow and become strong, healthy adults in some manner very different from what they experience in today’s institutional settings.

- Try to be a responsible, centered, loving person. It’s good for you and the world. But while bad people exacerbate social problems, they are not the problems. Likewise, good people are not the solutions. Though individuals make consequential choices, systems rule for the most part. The force of our dominant culture – as a system itself – and the many social, economic and political systems flowing within it drive and shape much of what we do, how we live and even many of the smallest choices we make. Car driving, as an example, is a terribly polluting, resource depleting, violent and isolating activity, but at the same time it is a very rational, life sustaining practice performed routinely by good people everywhere. Invisible systemic forces within the flow of our culture, and the structural manifestations of these forces, compel it. We will therefore have to change the cultural flow, create systems that work for people generally as they are. We will never get our current systems to work by trying to make people in them better, as many of us have been struggling to do. Look to see (and change) systems more and blame (credit or change) individuals less.

- Unlike physical systems, the social systems that shuttle us around, as powerful as they are, are also paper-thin. They are vulnerable to change, even rapid, dramatic change. They have structural and material manifestations that seem overwhelmingly formidable, but our social systems are ultimately sustained through the sponsorship of our minds. This principle was demonstrated in the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, an effect of a private conversation that snowballed into a movement with irrepressible force.

- Have faith that people can live equitably, sustainably and happily and that we are ambitious and inventive enough to fully recreate the way we live. ‘Where there is a will there is a way’ applies. Generating will requires awareness. For sure we are facing a profound social and psychospiritual challenge associated with cultural collapse and transformation. Humans are also stunningly adaptable. People are stuck, tethered to the dominant system, but as we become aware that our cultural Titanistad is really going down, enough people will scramble to invent and to cut paths for others to follow. One method our culture uses to bolster our faith in it is to convince us that we can’t live any other way:

• We’re not good enough (starting with innate depravity).

• It’s up to the people in power to make big change.

• The weight of change itself is too heavy (as if it’s all on my plate).

• Or, there simply is no viable, even thinkable, alternative to the basic competitive, hierarchical framework we’ve been living under.

Confront and challenge these familiar mantras as they creep into your mental projections.

- Look out for and pay attention to forward-reaching experiments. For some time, cultural innovators have been trying to experiment a way out of the dominant mode of living. Many of these social experiments are small, perhaps even conventional-looking trials. Many fail, which is par for the course of change. In trying to assess an experiment in this regard, ask yourself, ‘Does this experiment point to a world, say ten or twenty years out, that I would want to live in if the experiment were to succeed?’ I would cite Gaviotas, of rural Columbia, and the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative, of Boston, as two large-scale examples that inspire this kind of change. Catch yourself dismissing outright any person or group trying or saying something strange and different, then lend support to those pointing to a world you really want for you and our children.

- Don’t get stuck on, or worry over, what the world or your part of it is going to look like or how everything is going to fit together once the cultural dust settles. Contemplating ‘What if’ and ‘How are we going to’ obstructions might itself be the biggest obstruction. We have to move forward and out of where we are. A mass redeployment of creative energy and focus, driven by cultural shift, will produce results that are unimaginable to us now. ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’. Internalize the necessity.

- The dominant cultural vision is not one of global diversity, but global assimilation. It imagines every person living essentially the same way, speaking the same language, trading in the same currency at the same store. Assume that creating a new way of life in the ashes of this vision will be closer to creating new ways of life. The tribal/partnership system has a very good and long track record as a basic form of social organization for humans, but:

a) this form allows for genuine cultural diversity and countless ways of living beyond the basic form;

b) people may invent civilizational forms that work in ways our current form doesn’t; and

c) there are options and possibilities other than these two basic forms.

- As you free your thinking in these ways and relieve yourself of the burden – in your mind at least – of trying to make our systems work, encourage others to do the same and link up with an experiment in progress and/or innovate yourself. But even if you make no outward change in your life, this perspective shift will bring us significantly closer to a much, much better world, especially if you risk a conversation now and then. How we perceive and how we think are powerful forces of change.

- Find like-minded people to support and to support you. There are millions of people suffering various kinds and degrees of oppression and desperation as they try, often in isolation, to negotiate our troubled world. When hands and minds are joined and we begin to see that the source of our trouble isn’t located in us, only some of the symptoms, we create a bond with enormous potential for change. ‘Where there are two or more gathered’ for this kind of conversation and mutual support, anything can grow from it. There is a ‘tipping point’ somewhere in this social transformation and your small contribution is very likely a needed one. As such, it is also a decisive one.

I have to honestly think of myself as deeply cynical and hopeless in relation to what I believe our cultural systems and institutions can ultimately provide us. A new deal with the old dealers won’t save us. New dealers in the same game won’t either. A new game, or an assortment of new games, might. The needed change is fundamentally a cultural change, not a piece of legislation or a piece of technology, and it is a change that is struggling from many directions to break through. The mainstream culture is focused on news-making individuals, institutions and events – not systems – so this cultural shifting is relatively invisible and under-reported. Have faith in it, be on the look out and maybe even jump in somewhere.

This essay, under the title “What We Think Is What We Get”, is from Jim’s new book, Positive Thinking in a Dark Age. It originally appeared in the online journal Swans Commentary.

Featured image by Santhosh Sivaramalingam

by DGR Editor | Dec 15, 2016 | Male Supremacy, Repression at Home

by Renée Gerlich

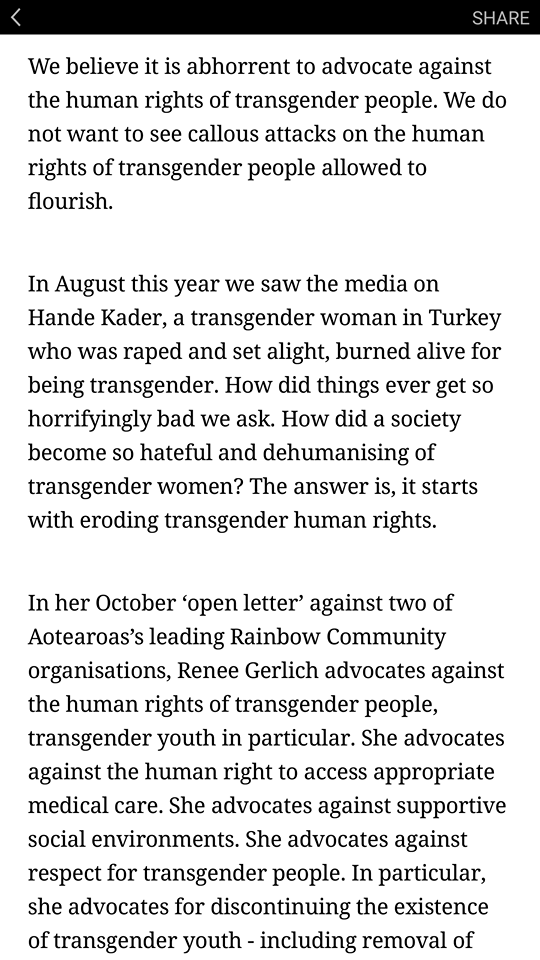

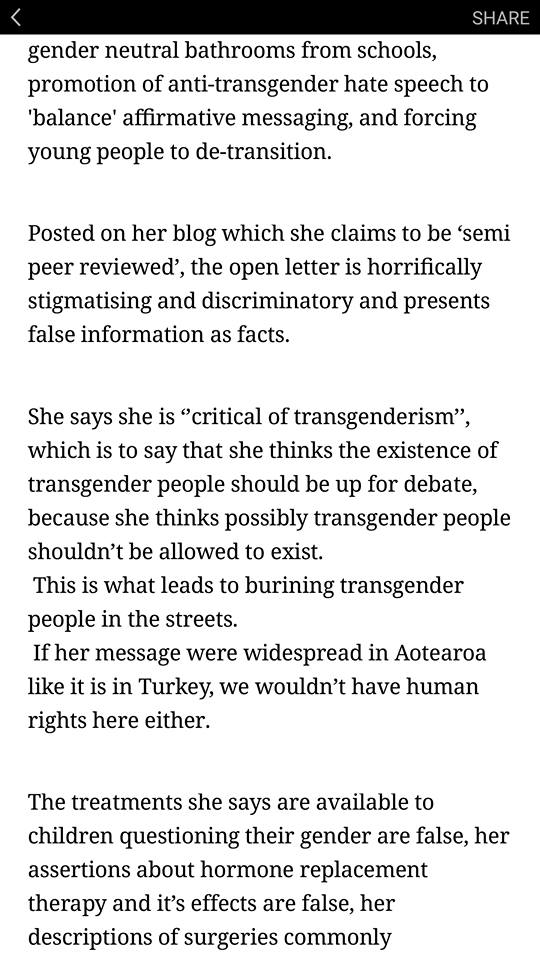

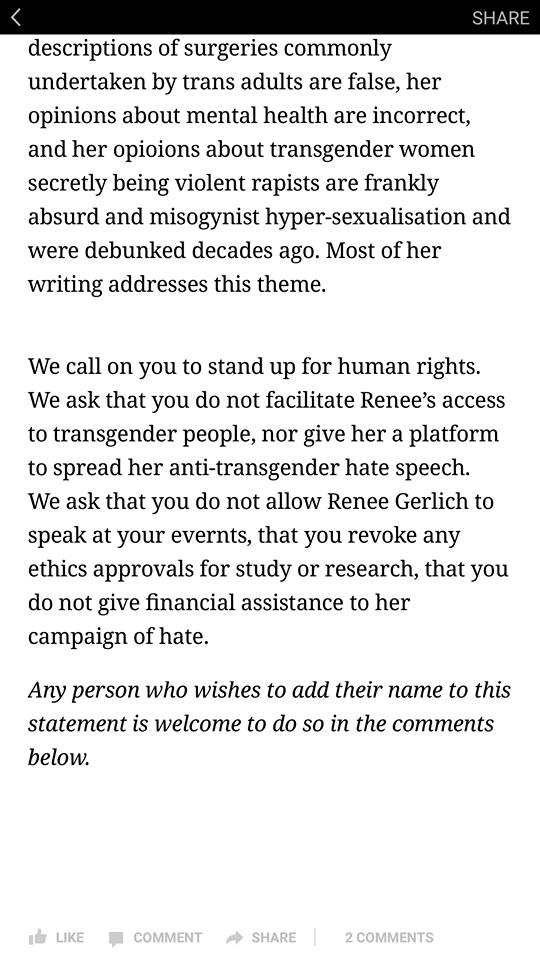

A New Zealand Prostitutes Collective (NZPC) spokesperson has instigated an online pact against yours truly. That might flatter me, if it weren’t so effective. It’s titled “Against Human Rights” – appropriately, since it exists specifically to help negate an individual woman’s rights to further education, a voice, and a livelihood. The pact (below) misrepresents my concerns about women‘s safety and the medicalisation of gender, and asks signatories to collaborate in withholding study, speaking and work opportunities from none other than myself.

This pact was instigated just after I was banned from the Wellington Zinefest, a community hand-made book market; and just before I lost my job. The reason Wellington Zinefest gave me for their ban was that my work is critical of both prostitution, and gender identity politics, and this makes me “unsafe”. Supporters of this ban then trained their attention on the impressionable new manager at my work, making her nervous with allegations of “hate speech”. Her response to that peer pressure has given me enough material for a five-page personal grievance for workplace bullying. I chose to resign.

So forgive me, but I have some bones to pick with the local liberal feminist scene.

I think feminism is in dire straits, and that is exemplified by my own situation, as well as other events we celebrate as successes. I would like to point the finger at whoever is ultimately, specifically responsible for manipulating women into the position we are in, on our turf; but that would take the kind of organised investigation I am not resourced for. All I can do is observe what we are doing in the name of “feminism”; consider who that is serving, what difference it is making, and compare that to the aims of feminism. Feminism is of course the movement to end rape and the systemic, sex-based oppression of women by men in power.

It looks to me like, in Wellington, “feminism” is in a state where it is insisted that women must be content with the routine and systemic pornification and commodification of our bodies. If we don’t like it, if we raise any issues with it – with the sex trade, or sex-based oppression – we’re treated with hostility. We are labelled prudes, not “sex positive” enough, blacklisted, and forced to recognise where our place is.

Women back-up dancers represent the male gaze in Ambition

The NZPC pact against me, if successful, is the kind of thing that could help put a woman on the street. This collaborative agreement to withhold opportunities from me is taking effect – I have lost my job – and whether or not I have other support, job prospects, or family behind me, is not of interest to NZPC or their followers. If I’m tracked closely enough (even my friends get text messages asking them, “how can you be friends with Renée?”) will I find another job in this city? This real-life pile-on has chances of real, destructive success. Indeed, that’s the appeal of witch hunts – they’re so easy to make effective. One woman rarely stands much chance against a mob.

If this pact did succeed in putting me on the street, I’d find what many women find: that the most readily available option to me, to sustain a livelihood, would be prostitution. This is not a far-fetched scenario, it happens all the time. That’s what keeps the industry alive – women are pushed out of options, and are left with that one.

Where would I go for support if it happened to me? To NZPC?

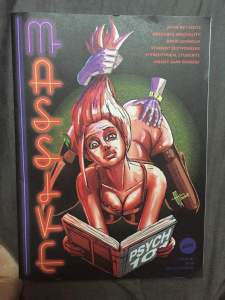

Magazine cover for Massive

Even the likes of Mike Hosking and Tony Veitch (a sports commentator who broke his partner’s back) don’t get this kind of treatment from liberals – pacts to cut off their options. I’m not comparing myself to these misogynists – but their example demonstrates who liberals truly get excited about hounding and destabilising. A Mike Hosking petition says, “We no longer wish to see or hear any more from Hosking on our TV screens” – nice and specific. I can’t even find a Veitch petition, and Veitch is still on air. Mine wants me indefinitely silenced – even though I have no platform – through an indefinite commitment to bad-mouthing.

In fact, Darkmatter performer Alok Vaid-Menon – a rape apologist and open misogynist, performed a slam poetry series earlier this year in Wellington. When I raised the issue of his public misogyny and rape and paedophilia justifications, I was told on no uncertain terms that I was not to speak about them, because Vaid-Menon is transgender. So he may have his global tour in spite of overt misogyny; I may not have my job, because of my feminist politics. Carwyn Walsh, the magazine editor who published this Massive cover also stayed in his job, while my public objection to it as offensive, was cited by the Wellington Zinefest committee as one of the reasons I was banned.

Again, the message is clear: I’m to know where my place is, as a woman.

Compare this to a lot of the other liberal feminist successes of late. They seem to almost be predicated on women flaunting some conformity to that very premise: we know where our place is. We, collectively, don’t mind being sexualised or pornified by men. We either aren’t aware of it, think it’s harmless, or we find it empowering and fun.

Hera Lindsay Bird, an incredible poet, rocketed to celebrity status this year with a stunning first book, creating her platform with an abundance of talent – and the poem Keats is dead so fuck me from behind.

City Gallery billboard

In 2015, the City Gallery placed this image, Gigi on their floor and on a Courtenay Place billboard. Regardless of her talent as a fine art photographer, the reproduction of pornography is one of Fiona Pardington’s major claims to fame. Local producer, beat-maker and musical powerhouse Estère just released an album in which the title track, Ambition, features “Magdelaine Lavirgin, bordello resident,” who “wants to be the United States President”.

There’s a “Free the Nipple” event coming up this month (“How far will you go for equality?”), asking women to get topless on Oriental Bay for gender equality, and that follows October’s Naked Girls Reading night. Both these events are international franchises. One guy told me he likes the idea of “Free the Nipple”, because he thinks it makes “porn redundant” – places it at his doorstep. There’s no shortage of leery commentary to be found about Free the Nipple from men online. That alone should make us question whether such events really bring about social change, and challenge to male power – or whether they co-opt feminist language to keep women in our place.

Women seem to be engaging in these events as activism because we somehow believe that normalising exposure of “the nipple” will help liberate “it” because men will become so accustomed to seeing female breasts in everyday settings, that they will no longer find them arousing, and then women will finally have the same privilege as men do to go topless. One of the problems with this notion is that it rests on the same habituation principle as pornography does, and the trajectory does not lead to liberation. What happens instead is that men are habituated and desensitised to the point of boredom, and then the game is lifted. In pornography, that means more explicit degradation and violence. Men did not used to like watching a woman being anally raped until she suffers rectal prolapse: they do now. It’s called “rosebudding”, and it’s the new trend.

The point is, that as long as power is still in men’s hands, and men are still buying women, using pornography, broadcasting misogyny, and capitalising from it all, while controlling every position and institution of influence there is – the habituation principle doesn’t work in women’s favour. If we are not taking power away, but we are taking more clothes off in more places, we are succumbing to the demands of men. If we are forcing or coercing other women to accept this status quo, we’re doing the patriarchy’s work for it, gratis.

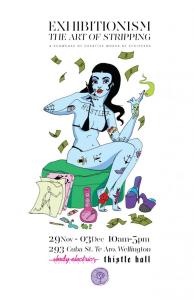

The Art of Stripping is an exhibition that recently showed at Thistle Hall, offering nipple plaster castings. The exhibition showed art by women who strip in Wellington strip clubs, claiming to demonstrate how “women involved in sex work are all unique and complex people”, though the show was still geared toward ultimately leveraging women’s creativity to legitimise the sex trade. Free trial pole dance classes and burlesque shows are never lacking in Wellington, which normalise that trade too; then of course there’s the usual barrage of objectifying advertising and media, that all these “feminist” activities still insist on distinguishing themselves from. They’re meant to be more sophisticated, avant-garde, political and literary than low-brow mainstream objectification.

Naked Girls Reading, an international campaign. Photo: Facebook event page

Estère’s Ambition music video, featuring Magdelaine Lavirgin (“bordello resident”) presents a telling commentary. Estère’s music has a rebellious, politicised, independent spirit. I Spy, for instance is a song about child poverty, inequality and the 1% caricatured through Baba Yaga imagery. To understand Estère’s punch is to know too that she can shake the world up from home in her pyjamas if she wants to: she makes music with a portable Music Production Centre called Lola, recording the slamming, for instance, of a cutlery drawer; the banging of a drumstick against a lampshade. Her search for rousing sound in her surrounds reminds me of the music company Stomp – except she is one woman.

Ambition presents Lavirgin as strident, not downtrodden. According to a meme Estère has made, “Emancipation of the afro” is one of Lavirgin’s campaigning platforms – she whips a blonde wig off at the video’s opening to liberate her afro by the end of the song, in a profound gesture of black liberation. Estère’s presence, spunk, creative integrity and production talent is jaw-dropping.

Estère’s Lavirgin is not a prostituted woman. She’s the “empowered sex worker” of liberal feminist mythology. She struts in a red cocktail dress pursued by figures in suits with cameras for heads that shine their lights on her. Presumably these camera-headed suits are pornographers, or perhaps they stand more abstractly for the male gaze; Lavirgin in any case, barely pays them notice. She’s just too sassy.

These pursuers eventually tear off their headgear and suits to reveal themselves as a group of women who then hoist up Lavirgin like a prize, decorate her with jewellery and fan her with star-spangled American flags in her presidential chair. To me, this video is a portrait and snapshot of the state of feminism in Wellington; the song a rather cutting anthem. It’s a depiction of the liberal feminists of Wellington and their downright worship of sex trade lobby spokespeople. The video contains vital motifs and messages about black liberation. Yet parallel to that, it tells a story of women, consciously or not, doing the patriarchy’s work for it: the promotion of pornography, and legitimising of prostitution.

It is possible to examine what really happens when a woman sex trade lobbyist – someone with vested interests in promoting the idea of “sex work” as “empowered” – gains access to the highest halls of power. It is not good news for women. Kat Banyard’s book Pimp State discusses how Alejandra Gil, a convicted sex trafficker, managed to lobby the U.N. and Amnesty International into developing policy of benefit to pimps and traffickers such as herself. She’d had a fifteen-year prison sentence for trafficking women and girls; it’s not hard to see why she’d want the sex trade legitimated. It doesn’t help the girls and women who are trafficked and prostituted; neither does our mainstreaming of this kind of lobbying.

Radio New Zealand seems in on this too. The Wireless published an article this year, about how “stigma” causes violence in prostitution (not pimps or johns), and RNZ did a terrible podcast on prostitution that was more like a lobby-produced advertorial.

It is worth considering too, that when Eleanor Catton (another magnificent creative and heroine of mine) won the Booker Prize, she did so for writing an 832-page novel in which the central protagonist is a prostituted woman, but rape is barely mentioned and prostitution hardly problematised.

I know that I will get in trouble with sisters for writing this; I’ll be accused of attacking women. I still think we need to be talking about the trends that might be keeping us “in our place”, keeping us immobile and unthreatening, while we enter a Trump-era of escalating violence, exploitation, attacks on reproductive rights, mass manipulation and hostility toward women.

With regard to that manipulation – consider that businessmen-pornographers have been grooming the market to make porn socially acceptable in the interests of capital gain since the 1950s. The first years of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy, Bob Guccione’s Penthouse and Larry Flynt’s Hustleron the shelves saw these pornographers work hard to normalise porn. By the 90s, bunny merchandise was being consumed by women everywhere – the bunny branding everything from stationery to pyjama pants.

“It was a very different world,” says feminist writer Gail Dines, “after Hefner eroded the cultural, economic, and legal barriers to mass production and distribution of porn.” It is now even considered up for debate now whether pole dancing is the best after school activity for 8-year-olds.

How did this shift to the mainstream happen? The answer is simple: by design. What we see today is the result of years of careful strategising and marketing by the porn industry to sanitise its products… reconstructing porn as fun, edgy, chic, sexy, and hot. The more sanitised the industry became, the more it seeped into the pop culture and into our collective consciousness.

Free the Nipple, Naked Girls Reading – these are global franchises, they are not grassroots community events. Where this pressure and facilitation and support comes from to run them, we need to understand. We need to understand that this is part of the normalisation of pornography, prostitution and porn culture, which are absolutely and inextricably intertwined with male capital gain, male entitlement, rape culture, sexual violence and the notion of women as property. That notion is shared by conservatives and liberals alike. Both these political groups are male dominated. Both have ways of capturing and co-opting of feminist language and ideals to keep women “in our place”.

Radical feminist midwife MaryLou Singleton sums it up beautifully. “There is liberal patriarchy and there is conservative patriarchy,” she says,

but I agree with Sunsara Taylor, the founder of Stop Patriarchy, that between the pope and the pimp there is really no fundamental difference. But right now, our options are being set up so that you can either align with the ‘Pope Lobby’ or the ‘Pimp Lobby’.

This manipulation and recruiting of women into sex-trade promotion through liberal politics has been successful to the point that porn and sex are now for all intents and purposes, synonymous. As Dines states, if you are anti-porn, you get slapped with the label “anti-sex”. This shows to what extent women have had the wool pulled over our eyes. Our sexuality istheir industry.

I have a fantasy of my own: of women rejecting that colonisation of our bodies and sexuality. Of women no longer pulling punches. What if Estère’s powerful contribution to black liberation struggle was combined with a rejection of prostitution as a tool of women’s subordination? What if Lola really held the power to boot the Chow brothers – known abusers who capitalise from exploitation of women in Wellington – out of town? I think she does hold that power.

What if Hera Lindsay Bird used her stir-up, startle-power to expose anti-feminism in the literary world? What if Fiona Pardington photographed johns and pimps and brought their abuse to light in chiaroscuro, instead of re-photographing already exploited women? If Eleanor Catton, after being called an “ungrateful hua” on air, called for a cull of commercial radio misogynists? If Hadassah Grace used her writing talent, slam voice and powers of intimidation to get White Ribbon ambassadors to check their phallocentric campaigning, re-open Christchurch’s Rape Crisis centre, provide some actual analysis, and perhaps support free self defence for women?

What if Free the Nipple was a women’s gathering, like the consciousness-raising, political gatherings of the 1970s? Like, if we all got bullied, banned and censored for talking sexual politics alone (fuck that)… what if we organised?

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2016 | Gender

New Books Highlight the Debate between Radical Feminism and Transgender Movement

by Robert Jensen

Within feminism there has been for decades an often divisive debate about transgenderism. With increasing mainstream news media and pop culture attention focused on the issue, understanding that feminist debate is more important than ever.

Two new feminist books that analyze transgenderism (Sheila Jeffreys’ Gender Hurts: A Feminist Analysis of the Politics of Transgenderism and Michael Schwalbe’s Manhood Acts: Gender and the Practices of Domination, which includes a chapter on “The Limits of Trans Liberalism”) are helpful for those who are concerned about the harms that result from the imposition of traditional gender roles but do not embrace the ideological assumptions and assertions of the transgender movement.

The propositions below are not taken directly from those books, whose authors may not agree with my phrasings. I am not trying to summarize their arguments but instead hope to bring greater clarity to the debate with a concise account of my position, which is rooted in a radical feminist analysis of sex and gender. I present these ideas as a series of propositions to make it easier for readers to identify where they may agree or disagree.

Biological and Cultural

We are a sexually dimorphic species, male and female. Although there is variation, the vast majority of humans are born with distinctly male or female reproductive systems, sexual characteristics, and/or chromosomal structure. Intersex people are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the definitions of female or male; the number of people in this category depends on the degree of ambiguity used to mark the category. Intersex conditions are distinct from transgenderism.

The biological differences between males and females that are tied to reproduction are not trivial; no species can ignore reproductive realities. Not all females have children, but only females can bear and breastfeed children, which no male can do. Therefore, human communities have always, and will always, recognize two distinct sex categories, male and female. There has always been, and always will be, some sex-role differentiation in human communities.

Other observable or measurable physical differences (average height, muscle mass, etc.) between males and females may be socially relevant depending on circumstances. Sex-role differentiation based on those differences may be appropriate if it can be shown to be necessary in the interests of everyone in a society. This claim is asserted far more often that is demonstrated.

People from varying ideological positions also claim that these biological differences give rise to significant differences in moral, intellectual, or emotional characteristics between males and females. While it is plausible that differences in reproductive organs and hormones could result in these kinds of differences, there is no clear evidence for these claims. Given the complexity of the human organism and the limits of contemporary research, it’s unlikely we will gain definitive understanding of these questions in the foreseeable future. In the absence of evidence of the biological bases for moral, intellectual, or emotional differences, we should assume that all or part of any differences in observed behavior between males and females in these matters are a product of cultural training, while remaining open to alternative explanations.

In short: males and females are far more similar than different.

Patriarchy

Today’s existing sex-role differentiation is the product of a patriarchal society based on male dominance. In that system, males are socialized into patriarchal masculinity to become men, and females are socialized into patriarchal femininity to become women.

In patriarchy, sex-role differentiation supports male power and helps make the system’s domination/subordination dynamic seem natural and normal. Moral, intellectual, and emotional traits are assigned differentially to each sex, creating what we today typically call gender roles. This patriarchal system of control—which is complex, adapting to changing conditions and to resistance—is designed to justify and perpetuate male dominance.

The gender roles in patriarchy are rigid, repressive, and reactionary. These roles constrain the healthy flourishing of both males and females, but females experience by far the most significant psychological and physical injuries from the system.

In patriarchy, gender is a category that functions to establish and reinforce inequality.

Radical Feminism

In contemporary culture, “radical” is often used dismissively as a synonym for “crazy” or “extreme.” In this context, it describes an analysis that seeks to understand, address, and eventually eliminate the root causes of inequality.

Radical feminism opposes patriarchy and male dominance. Radical feminism, which challenges the naturalizing of the process by which patriarchal societies turn male/female into man/woman, rejects patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender roles.

Radical feminist politics addresses a wide range of issues, including men’s violence and sexual exploitation of women and children. Many radical feminists critique the gendered dress/grooming/presentation norms imposed on females in patriarchy, such as hyper-sexualized clothing, make-up, and ritualized behaviors of subordination, arguing for the elimination of these practices, not for males to adopt them as well.

The goal of radical feminism is a world without hierarchy, in which males and females would be free to explore the range of human experiences—especially experiences of love, whether sexual or not—in an egalitarian context.

Transgender

Transgender is defined as “A term for people whose gender identity, expression or behavior is different from those typically associated with their assigned sex at birth.” The transgender movement rejects the automatic sorting of males and females into the categories of man and woman, but does not necessarily reject gender roles. Some in the transgender movement embrace patriarchal gender roles typically attached to the cultural categories of masculinity and femininity.

While not all people who identify as transgender have sex-reassignment surgery or use hormones or other treatments to modify their bodies, the transgender movement as a whole accepts and/or embraces these practices.

Most radical feminists, who seek to eliminate patriarchy and patriarchal gender ideology, disagree with this transgender approach. Most radical feminists believe liberation is achieved through a political project that transcends patriarchal gender, rather than accepting those gender roles and merely seeking to allow people to move between the categories. Radical feminist politics focuses on challenging the patriarchal gender ideology that restricts the freedom of most individuals, especially women and others who lack power, to explore the fullest range of human experiences.

Nothing in a radical feminist analysis minimizes the social and/or psychological struggles of—nor provides support for violence against—people who identify as transgender or people who do not conform to patriarchal gender norms but do not identify as transgender. Radical feminism is not the cause of those struggles or the source of that violence but rather advocates for an egalitarian society with maximal freedom without violence.

Ecology

Many people, whether radical feminist or not, are critical of high-tech medicine’s manipulation of the body through the reckless use of hormones and chemicals (which rarely have been proved to be safe) or the destruction of healthy tissue to conform to arbitrary beauty standards (cosmetic surgery such as breast augmentation, nose jobs, etc.).

From this ecological approach, such medical practices are part of a deeper problem in the industrial era of our failing to understand ourselves as organisms, shaped by an evolutionary history, and part of ecosystems that impose limits on all organisms.

People are not machines, and treating the human body like a machine is inconsistent with an ecological understanding of ourselves as living beings who are part of a larger living world.

Public Policy

The state should not limit people’s freedom to choose, when those choices do not harm others. Disagreements can, and do, arise over identifying and assessing harms.

Transgender claims have led to a variety of policy debates, especially concerning the integrity of female-only spaces that are designed to foster a sense of safety and expressive freedom for females generally (such as cultural institutions) and particularly to create safety for females who have been victims of male violence (such as rape crisis and domestic violence centers). Forcing female-only spaces to accommodate people who identify as transgender reinforces patriarchy as a system and harms individual females.

Public funding for sex-reassignment surgery (such as through Medicare) raises serious public health questions that cannot be resolved by simplistic freedom-to-choose arguments.

Transgender practices involving children that are questionable on public health grounds (such as the use of puberty blockers) raise serious moral questions about our collective obligation for children’s welfare.

Intellectual Practice and Rhetoric

As in any contentious political debate, angry and uncivil words have been exchanged. People on all sides should be respectful and careful in choices of language.

Labeling a radical feminist position on these public policy issues as inherently “transphobic” or describing radical feminist arguments on the issues as “hate speech” are diversionary tactics that undermine productive intellectual and political discussion. A critique of an idea is not a personal attack on any individual who holds the idea.

This critical analysis does not demand that people accept these principles in constructing an individual sense of self. These propositions are relevant to such individual decisions, but are presented in the context of collective decision-making about public policy.

Conclusion

Transgenderism is a liberal, individualist, medicalized response to the problem of patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms. Radical feminism is a radical, structural, politicized response. On the surface, transgenderism may seem to be a more revolutionary approach, but radical feminism offers a deeper critique of the domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of patriarchy and a more promising path to liberation.

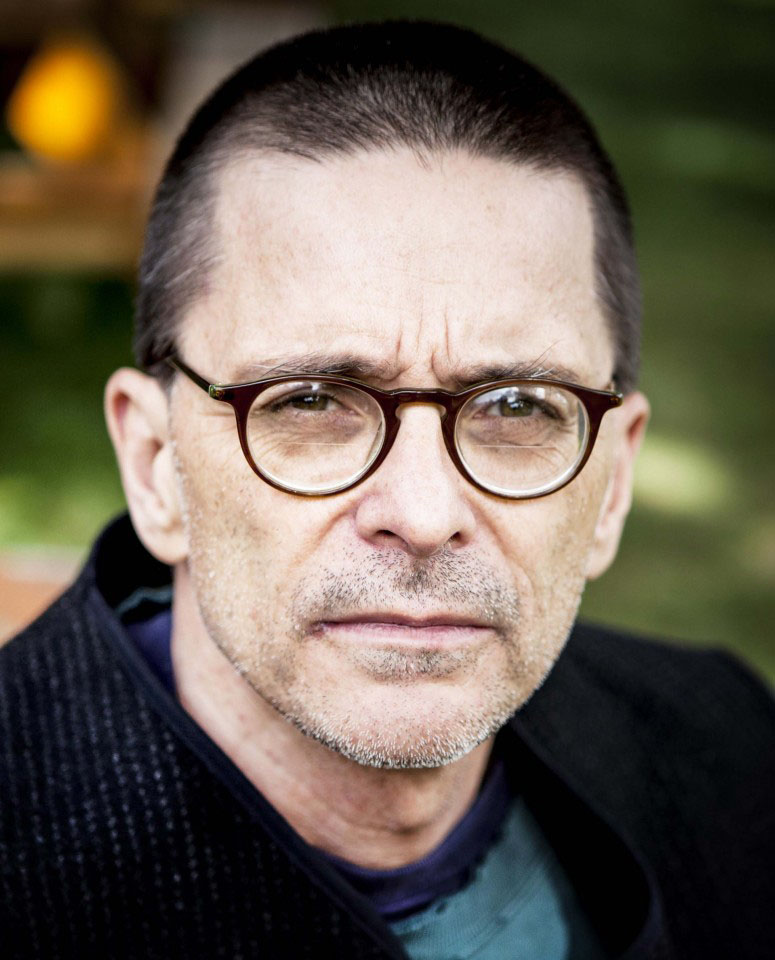

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include Arguing for Our Lives: A User’s Guide to Constructive Dialogue (City Lights, 2013) and Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity (South End Press, 2007).

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 1, 2016 | Gender

By Robert Jensen / Voice Male Magazine

A few weeks after I had published online a critique of the ideology of the trans movement, I was at lunch with a friend who has long been part of various movements for racial, economic, and gender justice and works as a diversity coordinator at a nearby university.

The meeting came on the heels of a local activist bookstore denouncing me in an email to its listserv, which had led to tense conversations with some comrades. At the end of lunch, my friend hesitantly brought up the controversy, and I got ready to hear her critique of my writing.

Instead, she leaned forward and said, “I don’t dare say this in public, but I agree with you.”

It was reassuring to know that someone whose work I respected shared my analysis. But it was disheartening to be reminded that a progressive/liberal orthodoxy on trans issues has left many people afraid to speak.

Most people involved in feminist movements know how bitter the trans debate has become, and those of us who identify with radical feminist principles are used to being labeled transphobic TERFs (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist), sometimes even accused of supporting a climate of violence against trans people. My goal here is not to assign responsibility for the breakdown of dialogue, but to point out one consequence of this state of affairs: Many people are afraid not only to disagree with the trans movement’s policy positions but even to ask questions about the underlying claims.

I have condensed into a question, a challenge, and a concern what I believe are the most important points in the trans debate.

The Question

If the claim of trans people is that they were born into one biological sex category, such as male, but are actually female, what does that mean? Is it a claim that reproduction based sex categories are an illusion? That one can have a female brain (whatever that means) in a body with male genitalia? That there is a non-material soul that can be of one sex but in the body of the other sex? I struggle to understand what the claim means, and to date I have read no coherent account and am aware of no coherent theory to explain it. (Note: The concerns of a people born intersex are distinct, raising issues different from the trans movement.)

The Challenge

If the claim of trans people is that they were socialized into one gender category, such as man/masculinity, but feel constrained by the category or feel more comfortable in the norms of the other category— that I can understand, partly as a result of my own negative experiences with the culture’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms. But those norms are the product of patriarchy, which means we need feminist critiques of patriarchy to escape the gender trap. While some in the trans movement identify as feminists, others embrace traditional gender norms, and in my estimation the movement as a whole does not embrace a feminist critique of institutionalized male dominance.

The Concern

As one pro-trans writer put it after reviewing the dramatic interventions into the body that happen in sex-reassignment surgery— which involves the destruction of healthy tissue—“It can seem and feel as if one is at war with one’s body.” Is this procedure, along with the use of hormones—including puberty-blockers in children— consistent with an ecological worldview that takes seriously the consequences of dramatic human interventions into organisms and ecosystems? With so little known about the etiology of trans, is the surgical/chemical approach warranted? I have developed these ideas in more detail in online essays (details below), which I hope people will read and consider, and I am working on a book that puts these issues in the context of a broader critique of patriarchy and the politics of rape/sexualized violence, prostitution/pornography, and trans.

The pornography issue was where I first encountered the splits between radical feminism and liberal/postmodern feminisms; a radical critique of the sex industry, in which men buy or rent objectified female bodies for sexual pleasure, often got one labeled a SWERF (Sex Worker Exclusionary Radical Feminist), as if a critique of institutionalized male dominance was nothing more than an attack on vulnerable women.

Is sex reassignment surgery consistent with an ecological worldview that takes seriously the consequences of dramatic human interventions into organisms and ecosystems?

But I continue to believe that a focus on systems of oppression is essential. Since my first exposure to radical feminism in the 1980s, I have been convinced that such feminist intellectual and political projects are crucial not only to the struggle for gender justice but for any kind of decent human future.

Is reasoned and principled argument, within and between movements and political perspectives, possible? In some settings, the answer these days appears to be “no.” For example, when I submitted a piece (see “Feminism Unheeded” below) to a website that had previously published my work, I warned the editors that it was a controversial subject. But they accepted the piece, made a few changes in editing, and posted it online. Within a couple of minutes— so fast that no one would have been able to read the whole article—a reader denounced me as transphobic, and the editors of the site, who had originally thought the piece raised important questions, took it down within a few hours (it was posted later on a different site).

Perhaps if these debates concerned purely personal matters, there would be no compelling reason for a public discussion. But the trans movement has proposed public policies—from opening sex/gender-specific bathrooms and locker rooms to anyone who identifies with that sex/gender, to public funding for surgery and hormone treat-ments—that require collective decisions. There’s no escape from the need for everyone to reach conclusions, however tentative, about the trans movement’s claims.

The trans movement is, of course, not monolithic, and varying people in it will identify politically in varying ways. But after two years of further conversations, reading, and study, I will reassert the conclusion I reached in the first article I wrote in 2014:

Transgenderism is a liberal, individualist, medicalized response to the problem of patriarchy’s rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms. Radical feminism is a radical, structural, politicized response. On the surface, transgenderism may seem to be a more revolutionary approach, but radical feminism offers a deeper critique of the domination/subordination dynamic at the heart of patriarchy and a more promising path to liberation.

One of the most common reactions I’ve had from people in progressive/liberal circles who agree with this statement but mute themselves in public conversations is that, in plain language, they just want to be nice—they fear that any question, challenge, or expression of concern will hurt the feelings of trans people. Sensitivity to others is appropriate, but should it trump attempts to understand an issue? Is it respectful of trans people to not speak about these matters?

A couple of months after the lunch described above, I had a conversation with a long-time comrade in feminist and progressive movements, who agreed with my analysis but said that she thought trans people had enough problems and that she didn’t want to seem mean-spirited in raising critical questions.

“So, your solidarity with that movement is based on the belief that the people in the trans community aren’t emotionally equipped to discuss the intellectual and political assertions they make?” I said. “Isn’t that kind of a strange basis for solidarity?”

She shrugged, not arguing the point, but sticking to her intention to avoid the question. I understand why, but those who make that choice should remember that avoiding questions does not provide answers.

Robert Jensen is a journalism professor at the University of Texas at Austin and author most recently of Plain Radical: Living, Loving, and Learning to Leave the Planet Gracefully (Counterpoint/Soft Skull, 2015). Information about his books, article archives, and contact information can be found at http://robertwjensen. org/.

For more extensive analysis of the issues raised in this article, Jensen recommends the following:

“Some basic propositions about sex, gender, and patriarchy,” Dissident Voice, June 13, 2014.

“There are limits: Ecological and social implications of trans and climate change,” Dissident Voice, September 12, 2014.

“Feminism unheeded,” Nation of Change, January 8, 2015.

“A transgender problem for diversity politics,” Dallas Morning News, June 5, 2015.

by DGR News Service | Apr 17, 2016 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Prostitution

Featured image: Mining in Seite Suyos, Bolivia. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons user Mach Marco)

By Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

When living the dream means others will die

I want to tell you three stories of winning and losing, of selfishness and sacrifice, of this culture.

Story one. Last spring I gave a talk in a small farming community in northwestern Illinois. I drove there from my previous talk in Wisconsin, passing through prime agricultural territory, which is to say cleared and plowed and empty cornfield after cleared and plowed and empty cornfield. When I got to my destination, a delightful retired teacher took me to see the last remaining unplowed prairie in the county. It was more or less downtown, between a busy street and yet another field devoted to agriculture. As he led me across the slender tract, I couldn’t stop weeping at the sight of flowers who were once common and now barely hanging on, butterflies who were once common and now barely hanging on, a mother goose protecting her nest. My (human) host told me that even though this is the last six acres left—just six acres out of 360,000 in the county—the neighboring landowner refuses to stop applying insecticides and herbicides, which of course drift across the fenceline.

That evening, after he introduced me, I took the stage, sat down, and faced a roomful of members of this farming community. I thanked them for their hospitality, told them of my experiences of the previous twenty-four hours, then said, “I think the plow is the most destructive artifact humans have ever created. It destroys every living being on a piece of ground and converts that land to solely human use.”

The members of this farming community looked back at me. One gave a grim smile, then said, “Those plows paid for our houses.”

I nodded, smiled just as grimly, and responded, “That’s precisely the problem, isn’t it?”

Story two begins with me receiving an issue of my alumni magazine from the Colorado School of Mines, which featured an article titled “Hitting Paydirt.” The article tells stories of several “tremendously rewarding” discoveries. There’s a twenty-six-year-old CSM grad who discovered a “virgin deposit” of 2 million ounces of gold. Another grad discovered what became mines in environmentally ravaged Ireland; environmentally ravaged, war-torn, and rape-plagued Somalia; and environmentally ravaged, war-torn, rape-plagued, and slavery- and child-labor-infested Mauritania (the article, of course, only listed the countries, not their misfortunes, many of which are caused or exacerbated by resource extraction). But the story I want to focus on happened in Bolivia, where CSM grad Larry Buchanan, in the employ of a transnational mining corporation (with an address in the Cayman Islands for tax haven purposes, and having since that time gone through bankruptcy and changed its name, emerging as essentially the same company but without the debt), saw what seemed like a promising geological formation. He looked more closely, and found at the center of the deposit a village, complete with ancient stone church.

Buchanan describes it like this: “The silver deposit lay on the surface, mineralized ledges cropped out everywhere around and below a little indigenous village of rock, adobe and grass thatch, called San Cristobal. The cobblestone streets were paved with silver-bearing rock. The rock walls of the houses literally were laced with silver veins. You couldn’t take a step without touching silver. But somehow [sic] it had been overlooked [sic] by everyone [sic].”

He unintentionally answers his own question as to why these indigenous peoples had never put in an open pit mine: “The Quechua culture of southwestern Bolivia is one of multiple gods and spirits, one with a profound respect for the earth in general and curiously [sic], for rocks in particular. They believe rocks are their direct ancestors, living souls that speak, think, feel emotions, and have distinct personalities.”

Buchanan again: “We discovered nearly a half billion tonnes of those silver-plated ancestors of the Quechua. [Yes, he actually said that.] After a year of work, the engineers calculated it contained nearly a billion ounces of silver, enough ore to last seventeen years of intensive mining. The computer models proved it feasible: the profits would be more than enormous and the mine would become a money-machine. [Yes, he actually said that.] It was a company maker, a world-class discovery, a perfect setup.” The only thing in his way was “that poverty-stricken little village right on top of it. If we wanted to make a mine, San Cristobal had to go.”

But the village didn’t go down without a fight—between white people. Buchanan’s wife was against moving the village and forced Buchanan to sleep on the couch, only relenting when Buchanan agreed that they would move to the village for a while to bear witness to the destruction they were causing (or, to use his words, “the opportunities we were offering the people”). This strikes me as a classic example of the conservative/liberal one-two punch of oppression, with the conservative perceiving the oppression as good in itself, while the liberal bears witness to the oppression without doing much of anything to stop it. So Buchanan and his wife watched as people dug up bones from the village’s four-hundred-year-old cemetery to move to their new compound eleven kilometers away. Buchanan joined village elders as they crawled around the cemetery to beg forgiveness for disturbing the dead. He watched as bulldozers leveled the village in just four hours. It was all very difficult for him: “There were times I was literally brought to tears when I would contemplate what the people lost due to my discovery.”

What was once a living village where people resided with their ancestors in the walls, their gods all around them, is now a huge toxic hole in the ground. But it’s all good. Buchanan believes the people now live better lives in the compound; transnational corporations have made 70 billion dollars; and, best of all, Buchanan and his wife wrote a book about it all. “I came to learn life holds so much more of value than just a few billion dollars worth of silver,” he says. Having learned this valuable lesson, Buchanan moved on to other projects, and believes he has just recently discovered another billion-ounce deposit somewhere else.

Story three involves New Zealand tae kwon do athlete Logan Campbell, who funded his dream of reaching the Olympics through being a pimp. He made a lot of money providing women’s bodies for men to use. He even made a video to recruit women into working for him. The advertisement had lots of pretty pictures of women leaping for joy in fields, standing contemplatively on beaches, and sharing warm hugs with happy children. One female voice-over gushed, “When I was a little girl, I used to dream of a life of liberty.” Another asked, “Did you enjoy that? I sure did.” One said, “I’m living the dream.” And another said, “You deserve it.” The ad never did describe precisely what the “it” is that women deserve, but I think most of us would agree that most little girls don’t dream of economically coerced sexual relations with strangers not of their choosing, of years of post-traumatic stress disorder, of broken psyches and broken genitals and broken lives.

The point, really, is that Logan Campbell did get to live his dream. He went to the Olympics on the bodies of women, just like Buchanan’s “tremendously rewarding find” came at the expense of San Cristobal and its deities, and just as plows pay for houses at the expense of everyone else in the biological community. These are all dreams of fame, accomplishment, money, even what we consider necessities, like the way we feed ourselves and the way we financially accumulate. The problem is, all these dreams are someone else’s nightmare.

These stories are not merely what is wrong with this culture, they are the fundamental ethos of this culture: the fulfillment of personal, social, and cultural dreams at the expense of all others. No sane culture would in any way extol any of these stories. So long as these stories are seen as the fulfillment of dreams, where the subjugation of others is not seen as subjugating them but rather as helping them to “live the dream”; so long as this culture considers actions that lead to the destruction of ancient ways of life as “rewarding finds,” where your own murderous behavior is seen as “offering opportunities” for the victims; so long as we find it not only acceptable but right and just to convert the lives of others and the life-support system of the entire planet itself into fodder for us, there is little hope for life on this planet.

Originally published in the January/February 2013 issue of Orion