by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 14, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Lierre Keith, author of Deep Green Resistance, has very clear views on

using nonviolent direct action. These views have been strongly influenced by Gene Sharp’s work. She states that the first question activists must answer is whether the political system they seek to change needs to be adjusted inside a basically sound institutional framework, or whether it requires more fundamental change. If the political system requires fundamental change, such change cannot be achieved by compromise or persuasion; it necessitates some kind of struggle that inherently involves conflict. Those who believe such institutions to be sound will “keep banging their head[s] against these institutions but the institutions will not yield to their fundamental principles.”

Keith points out that neither engagement in a struggle nor the use of force necessitates violence. At this stage the question of whether to use force or nonviolent tactics is premature; decisions about tactics come later.

Keith is critical of the liberal notion of consent, as she does not consider consent to be freely given. Consent is extracted from the ruled either ideologically or by terror and force. Therefore, the whole function of power is to extract consent. In Keith’s view, consent is actually a euphemism for submission. She explains how most of us don’t want to be forced to consent or submit, we want to be fully informed people who have actual choices to control the material conditions of our lives. We do not want to be given choices within such limited conditions; we want to actually control the conditions, so that our choices are choices in a meaningful sense. Keith states that, as a group, we can choose to remove our consent from the systems of power or not. If it is agreed that we wish to remove our consent, the question becomes: how best to do that? How best to get people to understand that they can remove their consent, and then, how to organise that withdrawal so the systems crumble?

Keith describes how nonviolent direct action impinges on the state’s power more directly than using force, because their power comes from the population. For Keith this is the important insight into why this technique works. When the population takes back their political, economic, and social power from the state then “the state is left with nothing.” Withdrawing power does not work if just done emotionally, and that this is where many on the left have gone wrong.

Another important point Keith makes is that nonviolent resistance to power makes visible the repression and structural violence of the system. Therefore, for a nonviolent campaign to work, those involved must maintain nonviolent discipline. Keith explains that such commitment is crucial to the success of this strategy because it reveals the violent overreaction of those in power. If the movement reacts with force, it will look like a riot to those observing (or those sitting on the sidelines trying to work out which side to join), and it will be difficult to distinguish between the violence of the state and the self-defense of the activists. Such a situation demonstrates how a diversity of tactics can be problematic – it can cause the movement to be viewed negatively and therefore make it less effective. Diversity of tactics does have a part to play in our struggle, but timing is important. I will discuss this topic more in a future post.

Keith is clear that verbally appealing to or begging the powerful for some kind of conciliation is not nonviolent direct action; it is a verbal appeal or a conciliatory effort. She states that these actions do not actually confront power but are merely a rational or emotional appeal. Nonviolent direct action doesn’t work because it is morally or spiritually superior, it works because it:

- exposes the violence of the state and demystifies power

- breaks through the psychology of the oppressed

- ultimately removes the support on which the powerful depend

Keith concludes that nonviolent direct action can work, but when determining our tactics we must always ask these key questions: is it going to work for the struggle we are in? Do we have enough people and time? It takes a lot of people and time to learn from the mistakes of initially using nonviolent direct action to get to a point when a movement can use it effectively. [1]

In Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, Ackerman and Kruegler argue that having a strategy and applying it properly are the most important factors determining the outcome of a nonviolent conflict.

They define strategy in this overarching sense as “a process by which one analyses a given conflict and determines how to gain objectives at minimum expense and risk.” [2] They also explain that “strategic performance is likely to be a significant, possibly the dominant, factor in the outcome of nonviolent struggle.” [3]

Ackerman and Kruegler also state the need to distinguish between policy, strategy, and tactics when addressing a conflict. Within this framework, “policy” consists of the objectives that define an acceptable outcome, and will therefore determine when the activists stop fighting. Strategy, in this more focused sense, is the plan for achieving the objectives, which may need to adapt to the group circumstances. Tactical decisions are related to how to initiate or respond to interactions with the opponent. [4] Ackerman and Kruegler identify twelve principles of strategic nonviolent conflict. [5]

Twelve Principles of Strategic Nonviolent Conflict

Principles of Development

1. Formulate functional objectives.

2. Develop organizational strength.

3. Secure access to critical material resources.

4. Cultivate external assistance.

5. Expand the repertoire of sanctions.

Principles of Engagement

6. Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control.

7. Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons.

8. Alienate opponents from expected bases of support.

9. Maintain nonviolent discipline.

Principles of Conception

10. Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic

decision making.

11. Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of the protagonists.

12. Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives.

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2gRtXp3qp8

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993, page 6

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 2

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 7

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 21 and read online

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 7, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the sixth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Gene Sharp is perhaps the most important modern advocate of nonviolence. In his 1973 three-volume book Politics of Nonviolent Action, he describes the theory behind the power of nonviolence, the categories of nonviolent actions, nonviolence strategy and organisation, and problems nonviolent campaigns and movements will need to overcome. The focus of his work is to encourage populations in countries with dictators to use nonviolent strategies and tactics to transition them into democracies. He also wrote From Dictatorship to Democracy, a condensed version of his earlier book that specifically focuses on overthrowing dictators through nonviolent methods.

Sharp argues that the sources of political power depend on the obedience of subjects; people obey because of habit, fear of sanctions, moral obligation, self-interest, psychological identification with the ruler, and absence of self-confidence. He contends that those in power rule by the consent of the people and that this consent can be withdrawn. Yet he notes that as power is controlled by a small number of people, systems and institutions of power are hard to change.

In Sharp’s model, nonviolent action is designed to be employed against opponents who use violent tactics, by creating a “special, asymmetric, conflict situation, in which the two groups rely on contrasting techniques of struggle, or ‘weapons systems’—one on violent action, the other on nonviolent action.” He believes that state repression is designed to be used against violent resistance, and so will have different results against nonviolent resistance. Sharp describes that it would be hard for the state to justify brutal repression against a nonviolent movement, so the repression will be more limited. He believes that the state may be concerned that overreacting will cause it to lose support, so it would prefer that the rebels use violence or force.

Sharp proposes a method called “Political Jui-Jitsu” to deal with violent repression. If nonviolent resisters maintain their nonviolence, then the state’s repression can be exposed in the worst possible light. According to Sharp, this will cause a shift in public opinion and power relationships in a way that favours the nonviolent resisters. If and when the state overreacts, this can cause sections of the population who were sitting on the sidelines to start supporting the protesters.

This theoretical advantage of nonviolence, however, assumes the repression is not too harsh to destroy the resistance movement, and that nonviolent resisters have the support of the majority of the population. Sharp does concede that if nonviolent actionists are few in number and lack the support of majority opinion then they may be vulnerable. His model also assumes that the state will use violence brutal enough, and that this violence will be publicised enough, to motivate a change in public sentiment.

In his writings, Sharp stresses the importance of strategy and tactics when planning a nonviolent campaign. According to this analysis, [1] key elements of successful nonviolent resistance movements include:

- an indirect approach to challenging the opponent’s power

- psychological elements such as surprise and maintaining morale

- geographical and physical elements

- timing

- numbers and strength

- the issue and concentration of strength

- and taking the initiative

Sharp also lists 198 methods or “weapons” of nonviolent action and identifies twelve factors that affect which methods could be used in distinct circumstances. [2] He divides the 198 methods into three categories: nonviolent protest and persuasion, nonviolent noncooperation, and nonviolent intervention.

Nonviolent protest and persuasion involve mainly symbolic acts of peaceful opposition or attempted persuasion. Nonviolent noncooperation occurs when activists deliberately withdraw their cooperation from the person or institution with which they are in conflict. This can include either economic or social noncooperation. Nonviolent intervention involves directly intervening in a situation in ways that may disrupt or even destroy behavior patterns, relationships, or institutions.

Sharp argues that for a nonviolent group to be successful, they need to achieve one of three broad processes in relation to the state or ruler: The regime needs to accommodate the ideas of the nonviolent group; or be converted by them; or the demands of the nonviolent group may be achieved through nonviolent coercion against the regime’s will.

This is the sixth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 492-500

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, page 115

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 2, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the fifth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Gene Sharp, founder of the Albert Einstein Institution, a non-profit dedicated to the study of nonviolent action, defines nonviolence as “the belief that the exercise of power depends on the consent of the ruled who, by withdrawing that consent, can control and even destroy the power of their opponent. In other words, nonviolent action is a technique used to control, combat and destroy the opponent’s power by nonviolent means of wielding power.” [1]

Nonviolence can be described as principled or pragmatic, reformist or revolutionary. Robert J. Burrowes describes how revolutionary nonviolence aims to cause significant, long term change and works towards a peaceful, egalitarian and sustainable society. [2] The Gandhian form of principled, revolutionary nonviolence is sometimes referred to as orthodox nonviolence. [3] Nonviolence can also be categorised as actions either of concentration or dispersal. Actions of concentration involve people coming together for marches and protests. Actions of dispersal would be boycotts and stay-at-home strikes, or other distributed action. [4]

In Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler differentiate between nonviolent sanctions and principled nonviolence, pacifism, or satayagraha. Sanctions are the use of methods to bring pressure to bear against opponents by mobilizing social, economic and political power without causing direct physical injury to the opponents.

Some nonviolence advocates argue that nonviolence and pacifism get confused, when they are in fact very different. [5] Principled nonviolence is synonymous with pacifism or Gandhi’s satayagraha or “truth force.”

In Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill describes pacifism as promising “that the harsh realities of state power can be transcended via good feelings and purity of purpose rather than by self-defense and resort to combat.” [6] Churchill argues that proponents of requisite nonviolence believe that nonviolent resisters must not inflict violence on others but may expect to experience violence directed against them. [7]

Peter Gelderloos describes how nonviolent activists seem to prefer one term or another—“pacifism” or “nonviolence”—some making a distinction between the two; he also notes that these distinctions are often inconsistent. Nonetheless, pacifists and nonviolent activists tend to work together with little concern for their chosen identity or ideological label. Gelderloos defines pacifism/nonviolence as a way of life or a method of social activism that avoids, transforms, or excludes violence while attempting to change society to create a more peaceful and free world. [8]

Gelderloos also takes issue with pacifists or nonviolent activists who distinguish themselves as revolutionary or non-revolutionary. He maintains that both groups work together, attend the same protests and generally use the same tactics. It is their shared vision of nonviolence, Gelderloos argues, and not a shared commitment to revolutionary goals, that primarily informs with whom they work. [9]

Bowser identifies pacifists as holding two unifying beliefs: beliefs in anti-war and anti-oppressive violence. He uses the term “pacifism” to mean ineffective, disengaging non-resistance and the term “active nonviolence” to describe offensive, creative action, where those practicing it put themselves in physical danger and engage in direct action, property destruction, and civil disobedience. [10]

“Civil disobedience” is a term coined by Henry Thoreau in 1849 in his essay of the same name. He describes civil disobedience as willful disobedience of laws considered unjust or hypocritical. Sharp defines civil disobedience as a “a deliberate, open and peaceful violation of particular laws decrees, regulations, ordinances, military or police instructions, and the like which are believed to be illegitimate for some reason,” adding that “civil disobedience is regarded as a synthesis of civility and disobedience, that is, it is disobedience carried out in nonviolent, civil behavior.” [11]

Lierre Keith, one of the founders of Deep Green Resistance, considers nonviolent direct action to be the most elegant political technique that has been used successfully over the last fifty years around the world. She describes how unlikely it is to shift the stance of those who have a profound moral attachment to true pacifism. She also maintains that those who support direct action using force or militant tactics need the support of nonviolent activists. She emphasizes that it is not helpful to get into conflict with these activists and that it is better to thoughtfully engage and disagree.

US attorney Thomas Linzey and his organisation Community Environmental Legal Defence Fund (CELDF) have developed a strategy described as “collective, non-violent civil disobedience through municipal lawmaking” to elevate community rights over corporate rights. The aim is to stop corporations coming into local communities and damaging the local environment or economy to make a profit.

Read on at What is Nonviolent Resitance? Part One

Featured image by Daniel Marsula/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Endnotes

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 4

- The Strategy of Nonviolence Defense: A Gandhian Approach, Robert J. Burrowes, 1996

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 139

- Unarmed Insurrections: People Power Movements in Nondemocracies, Kurt Schock, 2005

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 111

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, page 1998, page 45

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, page 1998, page 126

- How nonviolence protects the state, Peter Gelderloos, 2005, page 6, read online

- How nonviolence protects the state, Peter Gelderloos, 2005, page 7, read online

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence and the State, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, page 8, read online

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 315

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 23, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Before looking at nonviolence, it’s important to define what violence is, as it is often understood in varied and misleading terms. The aim of the next three posts on violence is to move away from the binary thinking of violence versus nonviolence and to appreciate the complexity of this topic.

In Endgame I: The Problem with Civilization, [1] Derrick Jensen maintains that many words and contexts are needed to approach a more complex understanding of what violence means and entails. He lists the following categories of violence in a discussion meant to provoke readers into (re)considering what forms of violence they oppose:

- unintentional and intentional violence

- unintentional but fully expected violence (when you drive you can fully expect to kill insects)

- distinction between direct violence and violence that is ordered to be done by others

- systemic (and hidden) violence

- violence by omission – by not acting leading to harm

- violence by silence – witnessing violence and not acting

- violence by lying – supporting those that carry out violence

Peter Gelderloos, author of The Failure of Nonviolence, writes critically of a typical human mindset, particularly by humans who occupy positions of institutionally maintained privilege: “If it’s done to me it’s violence. If it is done by me or for my benefit, it is justified, acceptable, or even invisible.” [2] He argues that violence doesn’t exist as an act but rather as a category; and that it is a concept regularly redefined by the state for the purpose of protecting and perpetuating systems of oppressive power. Gelderloos also asserts how common it is for people to describe things that they do not like as violent.

In Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon suggests that “an act is violent if its recipient experiences it as an attack or as deliberate endangerment.” [3] He offers a comprehensive review of the thinking on violence in relation to activism by asking two fundamental questions: what is violence, and can violence be justified?

Gordon makes a useful distinction between the violence of the anarchist movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the violence of today. The political violence of past centuries often involved mass armed insurrection and the assassination of heads of state and business leaders. Today, it tends to involve non-lethal violence during protests, property destruction, and clashes with law enforcement. [4]

Gene Sharp, known as the “father of the nonviolent revolution,” argues that violence is a way to influence behavior by intimidating people. His list of what constitutes violent actions includes conventional military action, guerrilla warfare, regicide (the killing of a king), rioting, police action, private armed offensive and defence, civil war, terrorism, conventional aerial bombing, and nuclear attacks. [5]

Bill Meyers argues that the corporate state intentionally confuses language used to discuss issues of violence in order to neutralise opposition: “It is important to distinguish exactly what is meant by violence, not being violent, and the ideology of Nonviolence. Most people have a pretty clear idea of what violence is: hitting people, stabbing them, shooting them, on up to incinerating people with napalm or atomic weapons. Not being violent is simply not causing physical harm to someone. But gray areas abound. What about stabbing an animal? What about allowing someone to starve because they cannot find means to pay for food? What about coercing behavior through the threat of violence? Through the threat of losing a job? Violence as a dichotomy, with the only choices being Violence or Non-violence, is not a very useful basis for political discussion, unless you want to confuse people.”

A good place to start is the Oxford dictionary definition of violence: “behavior involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something.”

In Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle seriously considers if inaction can be considered violent. He asks whether there is a definition or understanding of violence that can take into account the idea of inaction, the act of witnessing gross injustice and doing nothing within one’s power to effectively combat it. [6]

Boyle argues that when asking if an action is violent or an appropriate use of force, the intention of those that carry out the action needs to be considered. He offers the example of a tooth being pulled out either as an act of care by a friend if the tooth is causing a lot of pain, or by a torturer to inflict pain.

Boyle’s ultimate definition of violence is the “unjustified use of force in ways that are intentionally or culpably injurious to another entity, or insensitive to that entity’s own needs or The Whole of which it is one part. It encompasses actions that, through willful neglect, indirect conscious complicity, or the imposition of a set of conditions, contribute to the injury of another entity.” [7]

For Pattrice Jones, both concepts and context must be considered when defining violence. When many people say “violence,” they often mean some sort of violation that involves actual or the threatening of physical force. Following this logic, both force and violation must be present for an act to be considered violence. She observes that in law there is a distinction between violence and justifiable use of force, and between violent and nonviolent crime.

With regard to context, she notes that “if we understand violence to be injurious and unjustified use of force then we can never discern whether or not an act is violent apart from its context.” Thus, there is no need to waste time arguing about abstractions; justifiable use of force isn’t violence. We can move on to consider the more important question of how much force is justifiable in defence of human and non-human life and the earth. The line between force and violence can only be determined based on the context of the situation.

Jones poses intriguing questions when contemplating the use of force in any given situation: is the action likely to result in a desired outcome; is the same outcome likely to be achieved as quickly or certainly by some other means; and is the level of force being contemplated proportional to the level of harm that is trying to be prevented? [8]

This is the second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Endgame Volume 1, Derrick Jensen, 2006 page 399-400

- The Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 20/21

- Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon, 2007, page 78-95 https://libcom.org/files/anarchy_alive.pdf

- Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon, 2007, page 79-80, read online

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 3

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 38-43

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 45/6

- Igniting a Revolution, Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella, 2006, page 323

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 19, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Via Deep Green Resistance UK

2016 is predicted to be the hottest year since records began and environmental devastation is increasing. With so little time left and the whole world at stake, are the radical changes to halt climate change and ecocide being made? The simple answer is no, based on species extinction and the continuing global extraction and burning of fossil fuels.

Resistance movements need to be strategic to be effective. This involves selecting appropriate tactics to use and if a tactic is not effective, then choosing another. Nonviolent direct action (NVDA) is important to our struggle to stop environmental destruction, but it is only one tactic. I have found discussions about the appropriate uses of nonviolence, force, and violence unclear and often confusing, which led me to research the topic in greater depth.

Within activist communities and broader society, there are two widely-held perspectives on nonviolence. Some choose NVDA for strategic reasons. They may also see the importance of using force in some situations, if appropriate, but may or may not ever use force themselves. There are also those people who oppose the use of force no matter the circumstances. Any criticism in my articles is directed at the latter perspective as those who hold this perspective routinely mandate nonviolence across whole movements, and categorically reject the use of force or militant resistance, even in self defense. I will refer to people from this perspective as “nonviolence fundamentalists.”

In future articles I will explore what thinkers of the last 150 years have about these ideas, starting with violence. For now I will list those on either side of the debate that I have studied. There are of course others.

Nonviolence fundamentalists include:

Those that support NVDA and the use of force/militant resistance include:

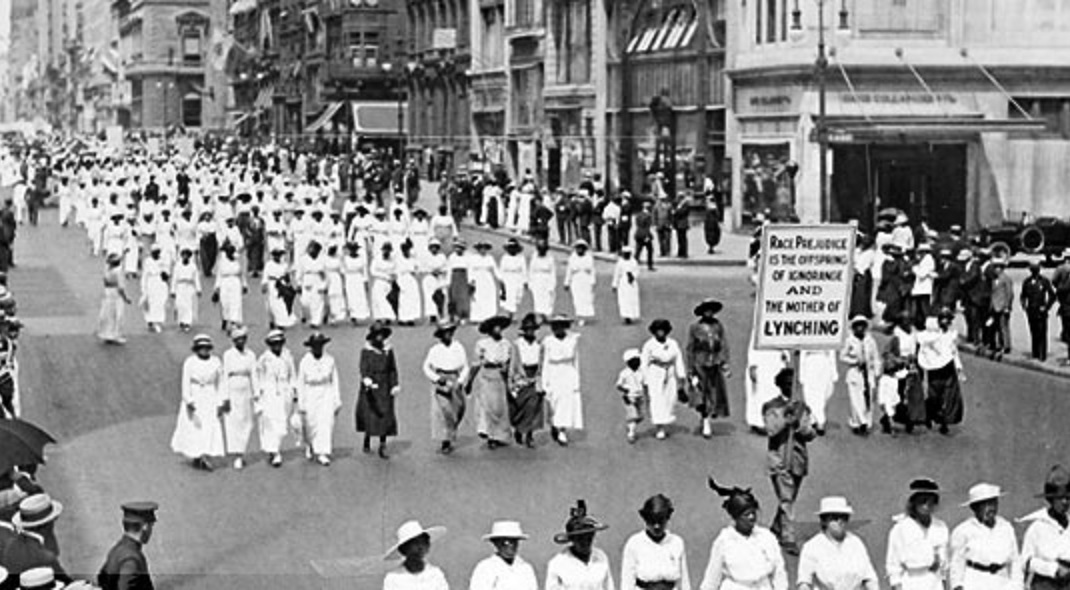

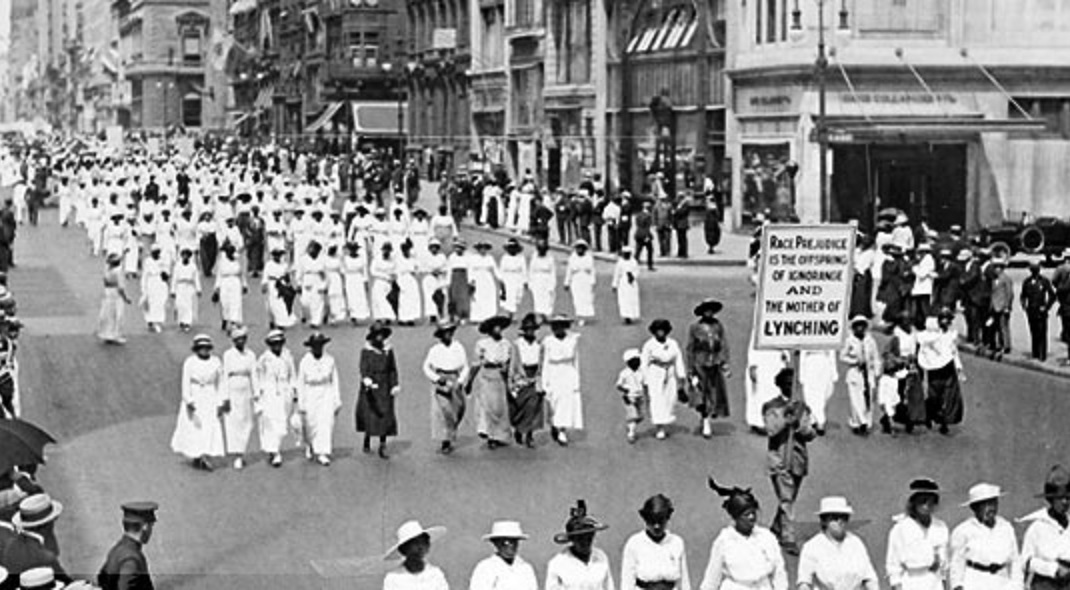

I would also add that most of the people that have written about violence, nonviolence, the use of force or militant resistance are men. I extensively researched women’s contribution to these topics and included everything relevant, without shoehorning them in to appear right on. Women have been very active in struggles using force and nonviolence tactics but it is mainly men that have written about it. This is consistent with men’s dominance in most areas of life. If I have overlooked anyone, I apologise and do set me straight. Some of the amazing women that have been so important to past struggles include Harriet Tubman, Blanca Canales, Angela Davis, Kathleen Neal Cleaver, Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst, Ulrike Meinhof, Ida Wells-Barnett, and Sojourner Truth.

Featured image: Nonviolent Direct Action at Livermore Lab, byJames Heddle/EON

This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org