by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 6, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the twenty-second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In Part One (read here), I explored the importance of viewing our resistance as acts of self defence and counter violence. I also discussed the two main arguments against using force, and that the moral question needs to be reframed. The decision about what strategy and tactics to use depends on the circumstances, rather than being wedded to one approach out of a vague ethical dogma.

Peter Gelderloos, an anarchist writer, reframes the question of if tactics are violent or not, by asking if the tactics are liberating when we are meant to be obedient consumers. Does the action result in space being reclaimed and held. Examples of this are the Spanish Civil War, Greece uprising of 2008, the Oaxacan state resistance to the Mexican government in 2006, and Hamburg 1986/7. [1]

If those fighting for a better world are going to be successful, then we all need to resist in the ways that make sense to each individual or group, and play to their strengths. At the same time, activists need to respect others ways of resisting, and work out how all these different methods can strengthen each other to build a movement. This approach is known as “Diversity of Tactics,” or more recently “Full Spectrum Resistance” or a “Holistic Resistance Movement.” [2]

Gelderloos describes how nonviolence fundamentalists view a social conflict as a chessboard where the movement’s leaders try to see or control all the pieces. The diversity of tactics perspective sees it is as a vast, opaque space with countless actors, whose needs are not always compatible as the struggle shifts. This involves agreeing zones for different tactics to be employed so tens of thousands of people can surround a summit and blockade; or disrupt with a combination of peaceful marches, sit-ins, lock-ons, tripods, barricades, riots in nearby business districts to draw of police, and then fight with them in the streets. [3]

Gelderloos explains that approach has been successful, but it requires all the groups with different tactics to work together. [4] It also requires the protest to not be centrally controlled, and that there be no central focus to the event, but many individuals and groups resisting as they see fit. [5] A recent example is the 2012 Barcelona uprising following a general strike, where several thousand people held space and some fought with the police and temporarily liberated space. [6] However, employing a diversity of tactics approach as part of a nonviolent mass movement campaign can be counterproductive if the campaign needs nonviolence discipline to be successful. If the aim of the nonviolence campaign is create a dilemma for the authorities or to get them to overreact then it is very important that nonviolence discipline is maintained. This is a very different strategy to the idea of holding space. Both have an important part to place in our resistance depending on the circumstances.

There are a number of different forms of direct action, with varying effectiveness through history. When different types of protest and direct action are combined they can make the overall movement for change more effective by opening avenues of resistance that are not easily co-opted or controlled by the state. Those that fail to see the importance of supporting all of the direct action tactics available, weaken the movement. To quote Ann Hansen from the Canadian militant group Direct Action: “Instead of forming a unified front, some activists see the sabotage of destructive property by protesters as being on the same level as the violence of the state and corporations. This equation is no more accurate than saying that the peace of a concentration camp is the same kind of peace that one finds in a healthy society. If we accept that all violence is the same, then we have agreed to limit our resistance to whatever the state and corporations find acceptable. We have become pacified. Remaining passive in the face of today’s global human and environmental destruction will create deeper scars than those resulting from the mistakes we will inevitably make by taking action.” [7]

Nonviolence advocates such as Marty Branagan generally don’t support the use of diversity of tactics, and some argue that the use of force by some discredits everyone at an action. In their view, if the majority of a group has decided to use nonviolent methods, then why “should they be forced to allow violent tactics to taint their protest?” [8]

Gelderloos respects those whose concept of revolution is to work for peace and follow a philosophy of doing no harm. He argues that the basis of respect is recognising the autonomy of others, and allowing and supporting them to fight for freedom in their own way. It’s appropriate to criticise those we respect, but not to try to make them become more like us: “the purpose of that criticism is to learn collectively at the point of conflict between our differences, not to turn them into Black Bloc anarchists.” [9]. He believes that we are all suited to different tasks, based on our temperament, abilities, experience and ideas about revolution. All of them are necessary; it’s a disservice to revolutionary principles to rank some of them over others. Glorifying illegal and combative tactics would create the same dynamic in which nonviolence fundamentalists create by only considering nonviolent methods. [10]

The legitimacy of nonviolent fundamentalists’ ideology must be constantly reviewed and assessed to determine if it is capable of achieving the social change it promises. Its lack of success does not mean abandoning all forms of nonviolent struggle, and only pursuing armed struggle. Instead we need to consider and develop the broadest possible range of thinking and action to resist the state. Rather than view different forms of resistance as separate components, they should be viewed as a continuum of activity from petitions, to demonstrations and protests, to the use of force in self defence. [11]

Jeriah Bowser offers a framework for resistance that includes both violent and nonviolent tactics. It offers a four-stage path for individuals from a disengaged pacifist to an engaged, empowered, and dedicated view of resistance towards oppression.

- The first stage is “colonization,” which most people experience when they cannot actualise their dreams, goals and desires.

- The second stage is “decolonization,” where individuals engage in an activity that breaks their view that they are weak and subservient, so they now feel empowered to “stand up for themselves.”

- Stage three is “active nonviolence,” with the use of empowered, creative and effective alternatives to passivity or violence.

- The final stage is “total liberation” – “a world built on the principles of love, community, connection, respect, mutual aid, egalitarianism, voluntary participation, and freedom where all living beings on the earth are free from oppressive violence.” [12]

It’s important to recognise that civilisation has stolen and hidden the history of rebellions and revolutions and the knowledge of the methods to carry them out. In simpler times, those suffering under oppression could rise up, and knew how to sabotage the machines and infrastructure of those in power. I echo Gelderloos in his call to relearn these important skills and knowledge. [13]

If we look at history we can see that the general pattern of movements is to start off nonviolently. If this does not prove effective, and state repression increases, some carry out more militant resistance. Examples of this would be the Suffragettes, African National Congress and Umkhonto we Sizwe in South Africa, the French Resistance, Irish Revolution, resistance to the oil companies in the Niger Delta – see Resistance Profiles for Ken Saro-Wiwa and Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, and later, Movement for the Emancipation for the Niger Delta and Niger Delta Avengers. That is the path we’re on in defense of the earth and we are at the early stages of militancy being considered justifiable for environmental protection.

With regard to thinking about new tactics, Derrick Jensen states:

“Bringing down civilization first and foremost consists of liberating ourselves by driving the colonizers out of our own hearts and minds: seeing civilization for what it is, seeing those in power for who and what they are, and seeing power for what it is. Bringing down civilization then consists of actions arising from that liberation, not allowing those in power to predetermine the ways we oppose them, instead living with and by–and using–the tools and rules of those in power only when we choose, and not using them when we choose not to. It means fighting them on our terms when we choose, and on their terms when we choose, when it is convenient and effective to do so. Think of that the next time you vote, get a permit for a demonstration, enter a courtroom, file a timber sale appeal, and so on. That’s not to say we shouldn’t use these tactics, but we should always remember who makes the rules, and we should strive to determine what ‘rules of engagement’ will shift the advantage to our side.” [14]

We in DGR are committed to the protective use of force and would never condone anything that results in any living being suffering. We have a long way to go convincing people that using force in defense of the living world is justified. It will mean convincing one person at a time. We need to build a movement that has this as its goal and then for that movement to act in defense of the living world.

Finally, I want to quote Mark Boyle’s vision of peace in our world:

“What I am searching for is an unrecognisable and long-since forgotten brand of peace. One which is free from the systemic violence that invisibly infiltrates almost every aspect of the ways by which we civilised folk meet our needs and insatiable desires. A type whose essence disrupts our tamed minds and reveals itself as much in the calm tranquillity of an ancient woodland as it conceals itself within the timeless chase between wolf and doe. A peace strangely imbued in a lioness’s ferocious defence of her cubs and the trilateral struggles of bear and salmon and streams, all of whose stories and ancestral patterns weave together the majestic fabric of The Whole and keep its harmony from unravelling at the seams. The peace I seek…is the peace of The Wild, one free from civilised, urbane notions of violence, nonviolence and pacifism.” [15]

Endnotes

- The Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 215-236

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 5/6

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 237

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 238

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 239-247

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 265-6

- Direct Action: Memoirs of an Urban Guerrilla, Ann Hansen, 2001, page 471

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence, The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 132

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 241

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 242

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, page 1998, page 94

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence and the State, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, page 97-114, read online

- The Failure of Nonviolence, page 275

- Endgame Volume 1, Derrick Jensen, 2006, page 252

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, page 3

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 24, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: RCMP in riot gear during raid on anti-fracking blockade, Mi’qmak territory, Oct 17, 2013. From Warrior Publications.

This is the twenty-first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

The destruction of our world isn’t an “environmental crisis,” nor a “climate crisis.” It’s a war waged by industrial civilisaton and capitalism against life on earth–all life–and we need a resistance movement with that analysis to respond.

I spent years as a liberal environmentalist, believing the propaganda from the state and the mainstream environmental movement that change will come about through top down solutions and technology fixes. Well, look where that’s got us – increasing destruction of the biosphere, accelerating species extinction and repeated failures of climate negotiations that are sold as successes.

When I finally understood that this approach wasn’t going to work, I got involved with the UK climate movement, but was unconvinced of their strategy and tactics. I respected the work being done but it looked hopeless considering the scale of the problems and the system causing them. In 2012, I read the Deep Green Resistance book. The book proposed a resistance movement forcing a crash of industrial civilisation and ending ecocide that made far more sense to me than anything else being offered. A strategy that is appropriate to the scale of the problem.

I see this response as self defence, or counter-violence. What is counter-violence? Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth coined the term to mean the violent, proportional response by colonised people to the coloniser’s violent repression. It has since been used more generally to refer to by any group’s use of force in response to state violence. [1]

Other terms for this response might be ”protective use of force,” “holistic self-defence” [2] or “defensive violence.” I find these ideas a relevant and useful way to frame how to respond to the destruction being inflicted on our world by industrial civilisation.

Self-defence actually discourages aggression and is a much better principle to use as a starting point than nonviolence. The definition of self-defence, agreed after thousands of years of experimentation, is that you can use the necessary amount of force to end an attack. Self-defence is a right and duty; a community that does not defend itself against aggression encourages further aggression. If aggressors are willing to kill or hurt anyone who gets in their way when taking what they want, there is little that those that practice nonviolence can do.

Most resistance movements in history have resorted to the use of force in response to the violence directed against them. They are simply defending themselves against violence by governments or the state. Mike Ryan articulates this well: “We accept the necessity of armed struggle in the Third World because the level of oppression leaves people with no other reasonable option. We recognize that the actions of Third World revolutionaries are not aggressive acts of violence, but a last line of defense and the only option for liberation in a situation of totally violent oppression.” [3]

So if freedom fighters in less industrialised countries are considered justified by many in using force against oppression, then why not in the industrialised world? Why not sabotage industrial infrastructure, if it amounts to self-defence? Perhaps because our conditioning to not act is too strong–we are too comfortable and have too much to lose. And therefore our collective inaction admits our participation in the oppression of other people.

When thinking about self-defence, we first need to be clear on what we mean by violence: Is fracking, deforestation, the damming of rivers, factory farming and the trawling of oceans violence? We also need to ask if non-humans who use force to protect their habitat, pack or family are violent? Your answers to this questions will affect if you think humans acting in self defence of their home or people are justified. [4]

Self-defence is a right we must reserve for ourselves. It we do not, then we invite violence attacks on ourselves, our families and our communities. Self-defence is the only thing that keeps violent institutions in check. It must also be combined with genuine solidarity with all non-human and humans under attack.

Assata Shakur, founding member of the Black Liberation Army and former Black Panther, clearly understood the need to fight back against the FBI and police who were killing black liberation leaders and activists. [5] Following the shooting of two New York police officers she said: “I felt sorry for their families, sorry for their children, but I was relieved to see that somebody else besides black folks and Puerto Ricans and Chicanos were being shot at.” [6]

The US communist Angela Davis describes how any revolutionary movement focuses on the principles and goals it is aiming to achieve, not the way they are reached. She described how society’s systemic or structural violence is on the surface everywhere, so is going to lead to violent events.

The former Black Panther Kathleen Neal Cleaver describes how the systematic violence against people of colour in the form of bad housing, unemployment, rotten education, unfair treatment in the courts–as well as direct violence from the police–led to the Black Panther Party forming to defend themselves.

I feel a deep sadness for what is happening to living beings and the natural world. I have been so well trained and conditioned by this culture that I struggle to really feel angry about what is happening. I think feeling angry is the appropriate response. We need to stop being so polite and positive, and connect with our anger about the destruction that is taking place. People alive now will be measured by those that come after by the health of what’s left of their landbases. [7] What matters is being effective, not moral purity about using only nonviolent tactics. We need a new Three R’s; instead of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, they should be Resist, Revolt, Rewild. [8]

The two main arguments against using force or violence are that it is morally wrong and ineffective. The moral question needs to be reframed. Instead of judging if an act of force in an isolated situation is justified, we need to ask what actions are necessary to ensure the least amount of suffering to living beings overall. This means seeing ourselves as connected and as part of nature, and then acting in defence of life. To quote Mark Boyle: “We need to defend the Earth with the same ferocity we would evoke if it were our home, because it is. We need to defend its inhabitants with the same passion as if they were our family members, because they are. We need to defend our lands, communities and cultures as if our lives depended on it, because they do.” [9]

There isn’t any one strategy or tactic that is necessarily more effective than another. It depends on the circumstances. Those that advocate the use of force certainly don’t argue that it’s a more effective tactic and that nonviolence should never be practiced. [10] To think that violence is not effective is deluded. Clearly violence is effective because that is what the state uses. Of course, the ends achieved through undesirable means may not themselves be desirable. Also most revolutionary and decolonisation struggles have involved nonviolent and counter-violence movements working in tandem. [11]

Bowser writes:

There is a very simple activity you can do to examine your own relationship with nihilism and resistance. Picture somebody you love deeply…Next, picture that person being viciously beaten to death by a gang of heavily armed policemen and soldiers…who are virtually undefeatable. What would you do?

The voice of nihilism, the cry of fears says, “It’s hopeless, you could never stop the beating, they all have guns and weapons and you only have your fists. Besides stopping the beating is illegal, and you don’t want to break the law, do you? Just stand there, try not to look, and be grateful that it isn’t you.”

The voice of resistance, the cry of love, says “I don’t care what the odds are or who says what is illegal, I have to do everything in my power to fight to defend what I love. I must spend all my energy and effort attempting to stop this horrible thing, even if it’s the last thing I do. I must fight to resist this atrocity, or I am not worthy of this person’s love.” [12]

I think that most would fight to defend their love ones, although some may be too damaged by this culture to do this. Ultimately we need to ask “What do you love and what are you willing to fight for?”

This exercise also brings up an important point about legitimate and illegitimate use of force or violence. The state likes to pretend that its use of violence is legitimate against foreign states, “terrorists,” or its own citizens. But in fact there are no legitimate governments in existence in the world. They all exist because they or their predecessors conquered an area and now dominate it with the use of, or threat of the use of, violence. “Government” by its very nature isn’t legitimate. It exists to concentrate wealth for the few at the expense of the many. We need to look to indigenous people to see how people can be organised in a legitimate way–small human-scale groups (about 100 people), where they choose their own leaders, have a council or elders and are committed to living in balance with their landbase.

Indigenous societies would not understand the modern legalistic view of “violence” or the state’s exclusive claim on violence. Violence (or the use of force) is something that has been taken from us and it is something we need to take back. [13]

Sakej Ward is Mi’kmaw (Mi’kmaq Nation) from the community of Esgenoopetitj (Burnt Church First Nation, New Brunswick). He speaks regularly on the resurgence of Indigenous Warrior Societies which act in defence of the land. On the topic of violence he explains that when you have an empire, you need a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. If citizens act in self defence, the state will classify this as illegal violence. The state will use violence and consider this a legitimate idea of the rule of law. He believes it’s very important to reject the imperialist notions of this monopoly on violence, that we should all be able to say “I can defend myself.”

This is the twenty-first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

Endnotes

- See Chris Hedges’ recent article http://www.truthdig.com/report/page4/the_great_unraveling_20150830

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 6

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, page 1998, page 147

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, page 31-2

- Assata: An Autobiography, Assata Shakur, 1987, page 349

- Assata: An Autobiography, page 339

- Endgame Volume 2: Resistance, Derrick Jensen, 2006, page 731

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, page 23

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, page 127

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2007, page 6, read online

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 89-91 and The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon, 1961, page 27-29

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, page 33, read online

- Introduction to Civil War in journal Tiqqun, pages 34 and 46, read online

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 8, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the fifteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

This post will look at if nonviolence is effective and why it has become the default tactic of activists in industrialised countries. I’ll then conclude this run of posts on the problems of pacifism and nonviolence.

Is Nonviolence Effective?

Nonviolent resistance dominates most activist groups and campaigns in industrialised countries. If it were effective as a tactic, wouldn’t things be better than they are? Perhaps many nonviolent campaigns and movements do not adequately plan out their strategy and tactics. A number of nonviolence fundamentalists do state that nonviolence is powerless against extreme violence, [1] which is perhaps a good description of the society we live in.

Ward Churchill is clear that revolutionary strategy and tactics need to be tested to see if they’re able to achieve the goal of liberation. [2] If a critical assessment is not done, then there is a risk that the dogma of nonviolence takes precedence over achieving the goals that have been collectively set. [3]

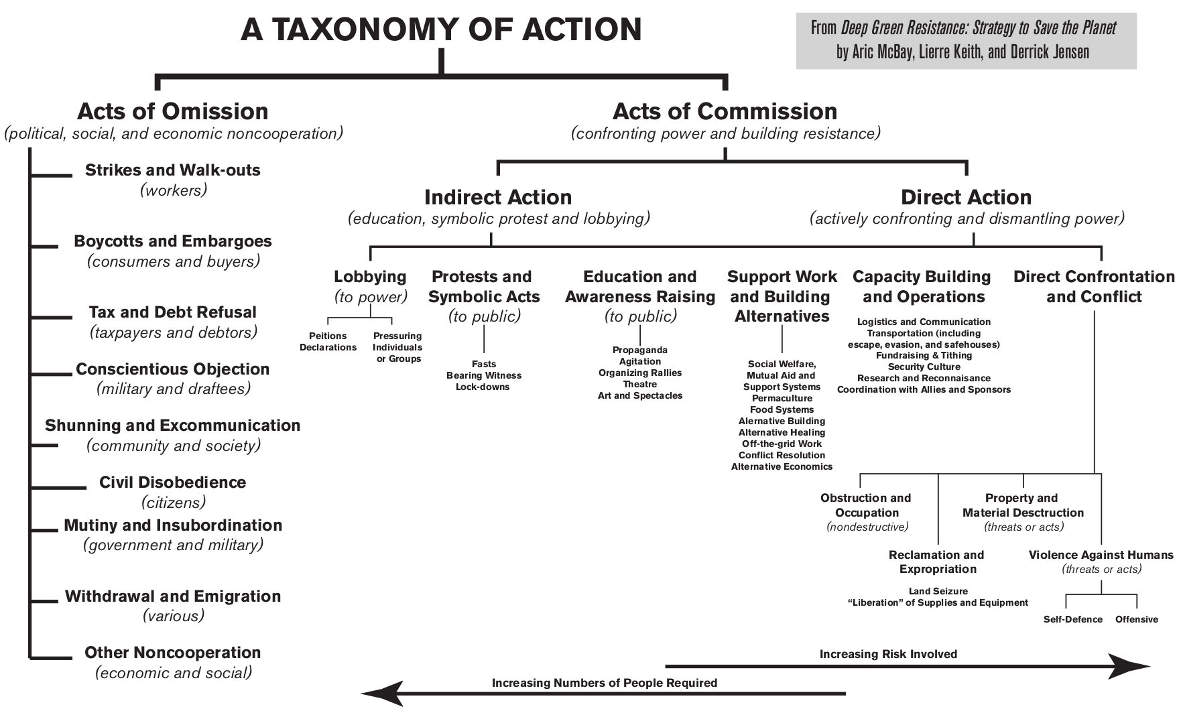

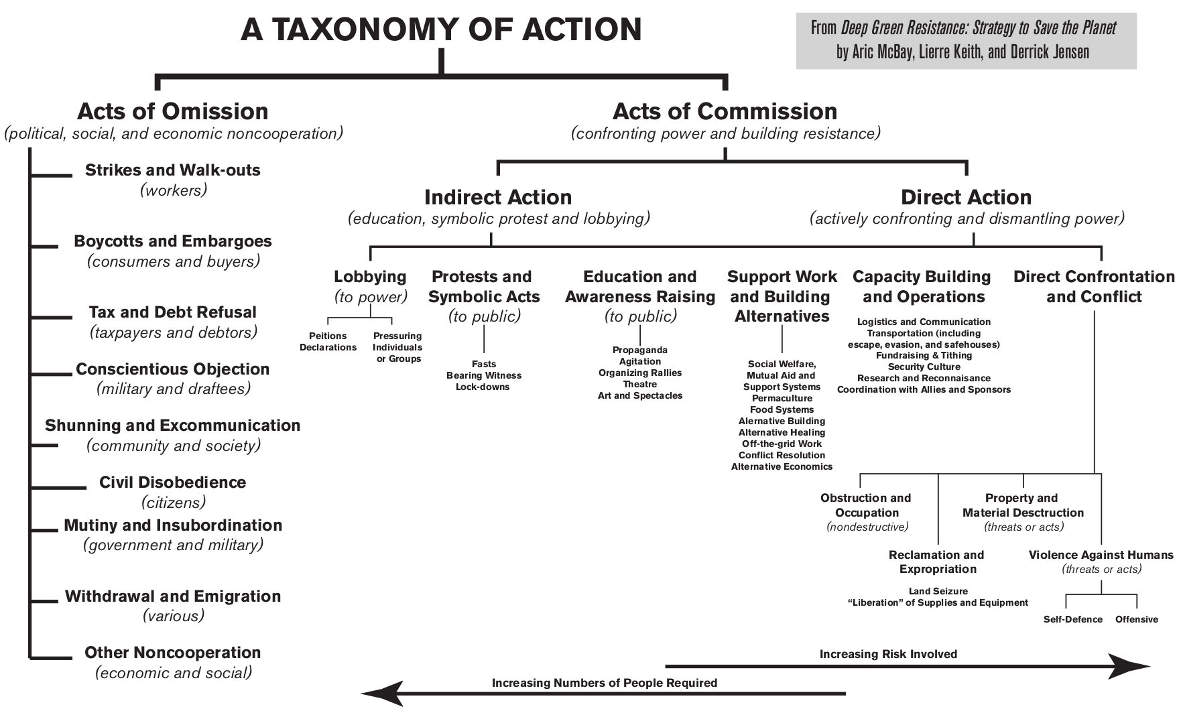

Using pacifist and nonviolent methods self-restricts activists to a limited number of tactics and gives little chance of surprise. Their responses become predictable to the state. Those advocating force are not doing so because they want violence, but because our options are so limited that at times it’s necessary. [4] We need to use nonviolent tactics to resist but it’s not enough. We need the whole range of tactics to be available to us if we’re going have a chance of a livable planet (see the Taxonomy of Action image below, and a full page version here).

Why Has Nonviolence Become the Default Tactic of Activists in Industrialised Countries?

Nonviolence became popular during the civil rights and anti-war movements, and has now become the accepted method of challenging the state. Many radical activists have internalised the taboo around the use of force and go along with the generally accepted view that the use of force is wrong under any circumstances.

There has been little intellectual or practical effort to examine the nature of revolutions and what’s required to ensure they happen in industrialised countries. This has created a vacuum, which has been filled with the most convenient and readily available set of assumptions – pacifism or nonviolent resistance. [5] Gelderloos puts this shift down to the disappearance or institutionalisation of the social movements of the past. [6] The heavy involvement of NGOs, mass media, universities, wealthy benefactors, and governments has made a move towards “civil” resistance all but assured. [7]

Another very important factor that has caused nonviolence to become the most common tactic in mainstream activism is that it allows people to protest and campaign without too much risk to themselves. They can feel that they are doing something to alleviate their guilt about the way the world is run and the amount of suffering taking place. They can bear moral witness, posturing as decent people but actually being complicit in the crimes that they purport to oppose by not doing what it takes to win. This is also known as the “Good German Syndrome.” [8]

According to Derrick Jensen, claims that militant actions will threaten one’s own resistance are similar to death camp inmates employing different approaches to survival. In these camps, some want to make things more comfortable, and perceive those that want to escape as threats to those who want a bit more soap or food. This causes a “constriction in initiative and planning” in those inmates who have not been completely broken and approach the daily tasks of survival with ingenuity. Indirectly, their field of initiative is constantly narrowed by those in control. This relates to the lack of effectiveness of our current resistance to the state; many are captives of this culture who have not been completely “broken,” but have been traumatised to the point that their “field of initiative” has been consistently narrowed by the state. Prolonged trauma results in a reduction in active engagement in the world because the victim learns that they are being watched, that their actions will be thwarted, and that they will pay dearly for them. [9]

Churchill outlines a process of radical therapy with five phases to work through the pacifist problem.

- Values clarification, where the need for revolutionary social change is explained. The difference between needs based on reality or feeling is explored. The goal of this phase is to determine if the person’s values are consistent with revolutionary change or reform.

- Reality therapy, which involves direct and extended exposure to the lives of oppressed people in industralised and less industralised countries. Those undergoing therapy would live in these communities for extended periods of time, eating the food and getting by on an average income for that community.

- Evaluation, which is a period of guided and independent reflection upon the observation and experiences in “the real world.”

- Demystification, at this point participants will argue that militant resistance is necessary but may not want to engage in it themselves. They may have never handled weapons, so are scared of them. In this phase, they are trained how to use weapons. This stage is not about training guerrilla fighters, but rather showing the participants that they can learn these skills—that a weapon is simply a tool, although a powerful and dangerous one—and therefore that the decision to use force is a tactical one.

- Reevaluation, in this phase participants will be helped to articulate their overall perspective on the nature and process of “revolutionary social transformation,” which includes their understanding of what specific roles they might take in the process. [10]

Where does this leave us? Jeriah Bowser argues:

[There is an] incredible amount of misunderstanding, narrow-minded dogmatism, and animosity that I obverse with many resistance communities. No matter what the social issue at hand, I have almost always found the parties involved to be rigidly polarized on the issue of violence: is it an acceptable tool to use for resisting oppression or not?

I believe both camps have much to offer the other, but we must first look at ourselves and examine our own positions critically, seeing the ways in which we might limit our own cause through hypocrisy, ignorance, privilege, personal fears and insecurities, and a misunderstanding of historical events. Then we can begin to understand the other side of the position, see the reasons that many people have chosen the alternative option, and ultimately try to find truths within their position that we can echo and sympathize with. To fail to consider and understand the other is to consciously remain ignorant. [11]

I completely agree with Bowser that those advocating force and those advocating nonviolence need to learn from each other, work together in solidarity where we have the same aims. It is achieving our collective goals that is important, not the tactics we employ—assuming these tactics aim to defend life.

Nonviolence fundamentalists paint those who think it might be necessary to use force as evil; but they all want the same thing: a just, sustainable world. The choice between using non-violence or force is a tactical decision. Those who advocate for the use of force are not arguing for blind unthinking violence, but against blind unthinking nonviolence. [12]

People who care about living in that just, sustainable world need to truly commit to their passion and act in whatever way makes sense to them. It is up to each individual and community to decide how to resist. The ultimate arbiter should be effectiveness. It is not right for others to judge those who choose to use force in service of revolution, especially if they are white, male and privileged.

Ultimately, the choice is not between nonviolence or violence, but between action and inaction .

This is the fifteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 59

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 93/4

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 137

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 92-4

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 89

- e.g. anti-war movement, environmental movement

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 13-14

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 14

- Derrick Jensen is referencing trauma expert Judith Herman in Endgame Volume 2, Derrick Jensen, 2006 page 724-6

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 95-102

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State Paperback, Jeriah Bowser, 2015, page 38, read here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 4

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 30, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Derrick Jensen

When I find myself in times of trouble, I’m less interested in Mother Mary’s wisdom than I am in Joe Hill’s: Don’t mourn; organize.

There’s a sense in which Trump’s election is a surprise, similar to how we somehow seem to be continually surprised when easily predictable negative consequences of this way of life come to pass. So we’re surprised when bathing the world in insecticides somehow causes crashes in insect populations, when covering the world in endocrine disrupters somehow leads to the disruption of endocrine systems, when damming and dewatering rivers somehow kills the rivers, when murdering oceans somehow murders oceans, when colonialism somehow destroys the lives of the colonized, when capitalism somehow destroys communities and the natural word, when rape culture somehow leads to rape, and so on. And we’re surprised when a racist, woman-hating culture elects a racist man who hates women.

But there are also many senses in which the rise of Trump or someone very like him was entirely predictable.

An empire in decay leads to a desperate push to the fore of values manifested by Trump: woman-hatred, racism, the scapegoating of those who impede empire, and a willingness to do whatever it takes to maintain that empire, to “make America [Greece, Rome, Britain, China] great again.”

When those who have been able to exploit others with impunity find their way of life (and more to the point, the exploitation and entitlement upon which their way of life is based) crumbling, what do they do?

We’ve seen this before. Why did lynchings of African-Americans go up soon after the Civil War and the end of chattel slavery? Why did the KKK rise again in the 1910s and 1920s? What is the relationship between Germany’s economic collapse in the 1920s and the rise of Nazi fascism?

Nietzsche provides one answer: “One does not hate when one can despise.”

So long as one’s exploitation of others proceeds relatively smoothly, one can merely despise those one exploits (despise, from the root de-specere, meaning to look down upon). So long as I have unfettered access to the lives and labor of, say, African-Americans, everything is, from my perspective, A-Okay. But impinge in any way on my ability to exploit, and watch the lynchings begin. The same is true for my access to other so-called resources as well, whether these “resources” are “timber resources,” “fisheries resources,” cheap plastic crap from China, or sexual and reproductive access to women. So long as the rhetoric of superiority works to maintain the entitlement, hatred and direct physical force remain underground. But when that rhetoric begins to fail, force and hatred waits in the wings, ready to explode.

Oh, but we wouldn’t do that, would we? Well, what if someone told you that no matter how much you paid to purchase title to some piece of land, the land itself does not belong to you. No longer may you do whatever you wish with it. You may not cut the trees on it. You may not build on it. You may not run a bulldozer over it to put in a driveway. Would you get pissed? How if these outsiders took away your computer because the process of manufacturing the hard drive killed women in Thailand. They took your clothes because they were made in sweatshops, your meat because it was factory-farmed, your cheap vegetables because the agricorporations that provided them drove family farmers out of business, and your coffee because its production destroyed rain forests, decimated migratory songbird populations, and drove African, Asian, and South and Central American subsistence farmers off their land. They took your car because of global warming, and your wedding ring because mining exploits workers and destroys landscapes and communities. Imagine if you began losing all of these parts of your life that you have seen as fundamental. I’d imagine you’d be pretty pissed. Maybe you’d start to hate the assholes doing this to you, and maybe if enough other people who were pissed off had already formed an organization to fight these people who were trying to destroy your life—I could easily see you asking, “What do these people have against me anyway?”—maybe you’d even put on white robes and funny hats, and maybe you’d even get a little rough with a few of them, if that was what it took to stop them from destroying your way of life. Or maybe you would vote for anyone who promised to make your life great again, even if you didn’t really believe the promises.

The American Empire is failing. Real wages have been declining for decades, for the entire lifetime of most people living today in the U.S. Indeed if real wages peaked in 1973, the last of those who entered the workforce in a time of universally increasing expectations are retiring. Sure, some sectors of the economy have done well, but what of those left behind? What of those whose livelihoods have been destroyed by a globalized economy, by the shifting of jobs to China, Vietnam, Bangladesh?

What happens to people in a time of declining expectations? What is the relationship between these declining expectations and the rise of fascism?

Two decades ago now a long-time activist said to me that Walmart and its cheap plastic crap was the only thing standing between the United States and a fascist revolution.

But cheap plastic crap can only put off fascism for so long.

There’s a difference between the ends of previous empires and the end of the current empire. That difference is global ecological collapse. Empires are always based not only on the exploitation of the poor but on the existence of new frontiers. Any expanding economy–and all empires are by definition expanding economies—need to continue expanding or collapse. America grew because there was always another ridge to cross with another forest to cut on the far side, always another river to dam, another school of fish to find and net. And the forests are gone. The rivers are gone. The fish are gone. The pyramid scheme upon which both civilization and more recently capitalism are based has reached its endgame.

And rather than honestly and effectively addressing the predicament into which not only we ourselves but the world has been pushed, it’s far easier to lie to ourselves and to each other. For some—and Democrats generally choose this lie—the lie can be that despite all evidence, capitalism need not be destructive of the poor and of the natural world, that the “invisible hand of Adam Smith” can, as Bill Clinton put it, “have a green thumb.” We just have to do capitalism nicely. And another lie—this one more favored by Republicans and manifested by Trump—is that the sources of our misery do not inhere in capitalism but rather come from Mexicans “stealing our jobs” and not remembering their proper place, from women no longer remembering their proper place, from African Americans no longer remembering their proper place. Their proper place of course being in service to us. And of course those damn environmentalists—“Enviro-Meddlers,” as some call them—are to blame for denying us access to that last one percent of old growth forest, that last one percent of fish. This lie blames anyone and anything other than the end of empire.

All of which brings us to the Democrats’ responsibility for Trump’s election. There has not been a time in my adult life—I’m 55—when Democrats have maintained more than the barest pretense of representing people over corporations. Through this time Democrats have functionally played good cop to the Republicans’ bad cop, as Democrats have betrayed constituency after constituency to serve the corporations that we all know really run the show. For generations now Democrats have known and taken for granted that those of us who care more for the earth or for justice or sanity than we do increased corporate control will not jump ship and support the often open fascists on “the other side of the aisle,” so these Democrats have calmly sidled further and further to the right.

Bad cop George Bush the First threatened to gut the Endangered Species Act. Once he had us good and scared, in came good cop Bill Clinton, who did far more harm to the natural world than Bush ever did by talking a good game while gutting the agencies tasked with overseeing the Act. Clinton, like any good cop in this farcical play, claimed to “feel our pain” as he rammed NAFTA down our throats.

What were we going to do? Vote for Bob Dole? Not bloody likely.

Obama made a big deal of delaying the Keystone XL as he pushed to build other pipeline after other pipeline, and as he opened up ever more areas to drilling. He pretended to “wage a war on coal” while expanding coal extraction for export.

What were we going to do? Vote for Mitt Romney?

For too long the primary and often sole argument Democrats have used in election after election is, “Vote for me. At least I’m not a Republican.” And as terrifying as I find Trump, Giuliani, Gingrich, Ryan, et al, this Democratic argument is not sustainable. Fool me five, six, seven, eight times, and maybe at long last I won’t get fooled again.

What we must finally realize is that the good cop act is, too, simply an act, and that neither the good cops nor the bad cops have ever had our interests at heart.

The primary function of Democrats and Republicans alike is to take care of business. The primary function is not to take care of communities. The primary function is not to take care of the planet. The primary function is to serve the interests of the owning class, by which I mean the owners of capital, the owners of society, the owners of the politicians.

We have seen over the last couple of generations a consistent ratcheting of American politics to the right, until by now our political choices have been reduced to on the one hand a moderately conservative Republican calling herself a Democrat, and on the other a strutting fascist calling himself a Republican. If we define “left” as being at minimum against capitalism, there is no functional left in this country.

For all of these reasons the election of Trump is no surprise.

But there’s another reason, too. The US is profoundly and functionally racist and woman-hating, nature hating, poor hating, and based on exploiting humans and nonhumans the world over. So why should it surprise us when someone who manifests these values is elected? He is not the first. Andrew Jackson anyone?

If that activist was right so many years ago, that cheap plastic crap from Walmart was the only thing standing between us and fascist revolution (and of course this cheap plastic crap merely pushed this social and natural destructiveness elsewhere) then he had to know also that cheap plastic crap is not a long term bulwark against fascism. It can only keep those chickens at bay for so long before they come home to roost.

The good cop/bad cop game is a classic tool used by abusers. You can do what I say, or I can beat you. You can sell me your cotton for 50 cents on the dollar, or I can hang you on a tree next to the last black man who refused my offer. Germans offered Jews the choices of different colored ID cards, and many Jews spent a lot of energy trying to figure out which color was better. But the whole point was to keep them busy while convincing them they held some responsibility for their own victimization.

I’ve long been guided by the words of Meir Berliner, who died fighting the SS at Treblinka, “When the oppressors give me two choices, I always take the third.”

By choosing the third I don’t mean simply choosing a third party candidate and perceiving yourself as pure and above the fray, as capitalism still continues to kill the planet.

I mean recognizing the truths about this whole exploitative, unsustainable, racist, woman-hating system. Recognizing that the function of politicians in a capitalist system is to act very much like human beings as they enact what is good for capital, as they facilitate, rationalize, put in place, and enforce a socio-pathological system. Recognizing that capital—including the functionaries of capitalism called “politicians”—will not act in opposition to capital because it is the right thing to do. These functionaries will not act in opposition to capital because we ask nicely. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism impoverishes the poor worldwide. They will not act in opposition to capital because capitalism is killing the planet. They will not act in opposition to capital. Period.

The power they wield, and the way they wield it, is not a mistake. It is what capitalism does.

Which brings us to Joe Hill. Don’t simply complain about Trump. Don’t simply throw up your hands in despair. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that the good cops would, if just unhindered by those bad cops, do the right thing or act in your best interests. Don’t fall into the magical thinking that capitalists will act other than they do. And certainly don’t take for granted that somehow magically we and the world will get out of this predicament, that somehow magically an anti-capitalist movement will spontaneously generate, or an anti-racist movement, a pro-woman movement, a movement to stop this culture from killing the planet. These movements emerge only through organized struggle. And someone has to do the organizing. Someone has to do the struggling. And it has to be you, and it has to be me.

A doctor friend of mine always says that the first step toward cure is proper diagnosis. Diagnose the problems, and then you become the cure.

You make it right.

So what I want you to do in response to the election of Donald Trump is to get off your butt and start working for the sort of world you want. Don’t mourn the election of Trump, organize to resist his reign, and organize to destroy the stranglehold that the Capitalist Party has over political processes, the stranglehold that capitalists and racists and woman-haters have over the planet and over all of our lives.

For more of Derrick Jensen’s analysis of racism, hatred, and the violence of civilization, see his book The Culture of Make Believe

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 20, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the thirteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Problem Two with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Nonviolence and pacifism as a Religion

Nonviolence fundamentalists do not deal well with the criticisms of their ideology and seem unphased by logical and practical critiques. Ward Churchill argues that it is delusional, racist, and suicidal to maintain that pacifism is always the most effective and most ethical approach. [1] He maintains that dogmatic pacifists (nonviolence fundamentalists) tend to deal with criticisms of their ideology by simply holding fast to their beliefs and reiterating pacifist principles. [2]

Pacifism and nonviolence originate from and share deep-seated ties to major religions. [3]

Derrick Jensen describes how pacifists put their self conception of moral purity above stopping injustice. [4] When he advocates for the use force in the fight to stop the destruction of the plant, liberal environmental activists and peace and justice activists often react with what Jensen calls the “Gandhi shield.” The Gandhi shield à la Jensen consists of repeating Gandhi’s name and invoking an inaccurate history to support dogmatic pacifism.

Peter Gelderloos in Nonviolence Protects the State dedicates a chapter to how nonviolence is deluded. This appears to be a trend noticed by many who must deal with the cult of dogmatic pacifism. Nonviolence fundamentalists are often caught up with principles, rather than focusing on what is needed to be effective. [5]

Nonviolence fundamentalists often base their worldview on a good-versus-evil dichotomy, and believe that they are good and positive for being peaceful and the state is bad and negative for using violence. This dichotomy results in a social conflict being framed as a morality play, with no material outcome. [6] I can see why some find the violence/nonviolence binary appealing; it’s straightforward but it doesn’t help us understand or act in the complex reality we all live in, especially if fighting for a better world.

Derrick Jensen states that for many pacifists, morality is abstracted from circumstance, meaning that direct violence is always wrong, under any circumstances, even if it might stop even more violence. [7] Does this mean the Jews that took up arms at the Nazi death camps were evil and wrong? Of course not. [8]

Problem Three with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Privileged and the Politics of the Comfort Zone

In Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos describes how nonviolence fundamentalists do not deal with oppression because of their often privileged position, and argues that nonviolence is often rooted in racist, statist, and patriarchal ideologies. Jeriah Bowser describes the typical “privileged pacifist”, who criticises those using violence and often does not see their own privilege. [9] Churchill describes the hypocrisy of pacifists supporting armed movements in colonized countries but being absolutely committed to nonviolence in the West. [10] It is not the place of pacifists or anyone in the West to tell oppressed people in colonial or neocolonial countries how to resist the oppression they face. [11]

Ward Churchill states that if you’re comfortable compared to others in your culture, this is a privileged position in society:

There is not a petition campaign that you can construct that is going to cause the power and the status quo to dissipate. There is not a legal action that you can take; you can’t go into the court of the conqueror and have the conqueror announce the conquest illegitimate and told to be repealed; you cannot vote in an alternative, you cannot hold a prayer vigil, you cannot burn the right scented candle at the prayer vigil, you cannot have the right folk song, you cannot have the right fashion statement, you cannot adopt a different diet, build a better bike path. You have to say it squarely: the fact that this power, this force, this entity, this monstrosity called the state maintains itself by physical force, and can be countered only in terms that it itself dictates and therefore understands.

It will not be a painless process, but, hey, newsflash: It’s not a process that is painless now. If you feel a relative absence of pain, that is testimony only to your position of privilege within the Statist structure. Those who are on the receiving end, whether they are in Iraq, they are in Palestine, they are in Haiti, they are in American Indian reserves inside the United States, whether they are in the migrant stream or the inner city, those who are “othered” and of color, in particular but poor more generally, known the difference between the painlessness of acquiescence on the one hand and the painfulness of maintaining the existing order on the other. Ultimately, there is no alternative that has found itself in reform there is only an alternative that founds itself — not in that fanciful word of revolution—- but in the devolution, that is to say the dismantlement of Empire from the Inside out. [12]

Problem Four with Pacifism and Nonviolence: Nonviolence Fundamentalists Complicity with the State

Another problem related to the last critique is nonviolence fundamentalists’ complicity with the state, when existing power structures aren’t challenged and the nonviolent activists “play the role of dissent,” which ultimately empowers and legitimises the state. Churchill describes how pacifism pretends to be revolutionary, with the “rules of the game” having been already agreed by both sides – demonstrations of “resistance” to state policies will be permitted as long as they don’t interfere with the actual implementation of those policies. [13]

Of course, not all nonviolence is so false, but the majority of pacifistic resistance could be described as a “performance.” The outcome is never in any doubt.

Nonviolence fundamentalist also criticise those who call for the use of force or violence, but will ignore the state violence happening every day. [14]

Bill Meyer makes the point in his essay that, contrary to expectations:

Nonviolence encourages violence by the state and corporations. The ideology of nonviolence creates effects opposite to what it promises. As a result nonviolence ideologists cooperate in the ongoing destruction of the environment, in continued repression of powerless, and in U.S./corporate attacks on people in foreign nations.”

Anarchist writer Peter Gelderloos has serious issues with nonviolent activists working with the police by giving them information (snitching); removing masks, which is effectively snitching; using cameras to take photos of militants; and planning march routes in cooperation with the police. [15] Of course, there is a legitimate place for creating “family friendly” resistance spaces and marches, but resistance must extend well beyond this.

Gelderloos describes how nonviolence fundamentalists often operate as “peace police” to control protests. Examples include policing resistance to the I-69 in the US midwest in the 1990’s and 2000’s, protests against the police murder of Oscar Grant in 2009 in San Francisco, and the protest march against the police murder of homeless man Jack Collins in Portland in 2010. [16]

Derrick Jensen describes how nonviolent protesters have turned on Black Bloc Anarchists for smashing shop windows. [17] Ward Churchill describes how pacifists have reported militants to the police and have worked to tone down actions to make them more symbolic. [18] It’s important to ask why white support for the Black Panthers disappeared when they responded to violent state repression with armed resistance. [19]

Nonviolence fundamentalists are very open about working with the police to inform on militants that might “ruin” their protest. Srdja Popovic in Blueprint for a Revolution promotes taking pictures of anarchists and uploading them to social media. Marty Branagan in Global Warming, Militarism and Nonviolence: The Art of Active Resistance, suggests forging links with the police to try to get them to defect to the protest movement.

For me, I can see why there might be resistance to Black Bloc activities at a nonviolent protest as described in post seven. I can also completely understand why individuals want to use Black Bloc tactics at another ineffective protest. But what is appropriate very much depends on the circumstances of each protest event. The use of militant resistance at a nonviolent protest can dilute and disempower the message and reduce the movement building potential.

With regard to talking or working with the police: I think that trying to convince police to join resistance movements is a good thing to do where the opportunity presents itself, of course being aware that the police may simply be trying to gather information from you. It’s a fine line to walk, and not for everyone. I do not think it is acceptable to work (or suggest working) with the police to inform on other activists.

This is the thirteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 84-86

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 83

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 83/4. Endgame Vol.1: The Problem of Civilization, Derrick Jensen, 2006, page 295 and 300

- Engame, page 298/9

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, Peter Gelderloos, 2007, chapter on nonviolence being deluded, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 52

- Endgame, page 296

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 53

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 111, Read online here

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 70

- How Nonviolence Protects the State, page 22/23

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 27/8

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 71-3

- Elements of Resistance: Violence, Nonviolence, and the State, page 40-5, Read online here

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 261-3

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 137/8 and page 126-9

- Engame, page 81-84

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 67

- Pacifism as Pathology, page 69

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org