by DGR News Service | May 26, 2020 | The Problem: Civilization

In this piece, Salonika explains how this culture prioritizes economic gains over human and natural welfare. She describes how series of toxic accidents in India (of which the Vishakhapatnam gas leak is one example) lays testimony to this fact. In such a culture, is it possible to hold the responsible actors accountable for their actions?

Vishakhapatnam Gas Leak: Who do We Hold Accountable?

By Salonika

On 7th of May, 2020, a gas leak on the outskirts of Vishakhapatman (R. R. Venkatapuram village) has killed 12 people, including 2 children, and injured 1000 others. Vishakhapatnam is one of the largest cities of Andhra Pradesh, the eastern state of India.

LG Polymers, along with other similarly damaging industries, were established in the outskirts of Vishakhapatnam in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. Within the five decades since then, urbanization has moved the city nearer to the industries.

Many fled their homes in the middle of the night. Some were fortunate enough to reach a place of safety, while others fell unconscious on the streets. At least 3 of the deaths were due to people falling unconscious under unfortunate situations: two people crashed a bike while fleeing the area; one woman fell off her window. Many more were found unconscious on their beds.

The gas, Styrene, caused itchiness in the eyes, drowsiness, light-headedness, and breathlessness. In severe cases, the gas causes irregular heartbeats, coma or death. A district health official stated that the long-term health effects of this accident is yet unknown.

The gas leaked from an LG Polymers plant around 2:30 AM, and spread around a 3 km (2 miles) radius. Workers reportedly failed to alert the local residents after they found out about the leak. The police were informed around 3:30 AM, and went to the scene, but had to retreat for fear of being poisoned.

It took hours before the situation could be stabilised. LG Polymers did not have any mechanisms in place to prepare for emergencies like this. This led the local youth, local police and personnel from National Disaster Response Force to act as first-respondents.

Who caused the leak?

Speculations have arisen suggesting that chemical reactions occurred during the lockdown in the plant due to inactivity, clogging the cooling systems, which caused the tanks to heat up eventually causing a leak. No inhibitors were found on the plant to slow the process in cases of emergency. The leak occurred after the operations on the plant restarted following the lockdown was eased in India.

LG Polymers (a South-Korean company) stated that it would be investigating the cause of the incident. It has also offered apology for those affected and promised support to affected and their families.

Meanwhile, the state Industries Minister, Goutam Reddy, stated that it appeared as if the plant did not follow proper procedures and guidelines during its reopening, and that legal action would be taken against the company. Investigators have also found that safety precautions had not been followed, calling it a “crime of omission“.

An official statement from LG Polymers itself suggests that management were aware of a possible disaster. Industries Minister Reddy has placed the burden of proof on LG Polymers to prove that there was no negligence on its part. A negligence and culpable homicide complaint has been lodged against the management of the plant.

LG Polymers have also admitted that it had expanded operations without due consent from regulatory authorities. On top of that, no preparatory mechanisms (a mandatory rule in India) were in place to handle an emergency state.

Contrary to this, other governmental and investigation authorities have issued statements that might suggest an act of compliance between the company and the authorities. The Director General of Police (Andhra Pradesh) claimed that all the protocols were being followed. Similarly, Chief Minister of the state stated that the company involved was a “reputed” one.

India: A history of toxic ‘accidents’.

When accidents become a regular phenomenon, is it even fair to call those ‘accidents’? Workplace accidents that kill humans and nonhumans, and pollutes natural entities (making the impacts last years, or decades, after the original accident) are not new to the country. Some of the most notable accidents being the Union Carbide gas tragedy (1984), Bombay docks explosion (1944), Chasnala mining disaster (1975), Korba Chimney collapse (2009), NTPC power plant explosion (2017), and Jaipur oil depot fire (2009).

The gas leak in Andhra Pradesh was one of three similar accidents within the same day in India. A paper mill in Shakti Paper Mill, Chhattisgarh (a state bordering Andhra Pradesh) hours before Vishakhapatnam accident, due to which seven workers were hospitalized. Similarly, later the same day, a boiler exploded at Neyveli Lignite Corporation in Tamilnadu (southernmost state of India), killing 1 and injuring 5.

These leaks comes just weeks after the coal plant accident in Singrauli. The coal plant leak itself was third of its kind in the past 12 months in the same area.

The new gas leak has also reminded some of the tragic Bhopal gas leak in 1984. More than 40 tonnes of deadly chemicals used in the manufacture of pesticides were released, resulting in an estimated fatalities between 16,000 and 30,000. After 35 years, the effects of the gas leak is still being felt among new born babies. The maximum charges faced by the perpetrators of the “world’s worst industrial disaster” was a two-years’ sentence in prison, and a fine of ₹5,00,000, sentenced 25 years after the incident.

Where do we place the accountability?

Perhaps the gas leak was a result of the Indian government’s premature decision to reopen the economy despite increasing cases of Covid-19 infections.

Perhaps the regulatory agencies are also at fault for failing to ensure that proper procedures were followed by the management while reopening the plant. In a place where enforcement of regulations have always been lax, the temporary closure of plants during the lockdown only exacerbated the problem.

Or perhaps, the plant’s management are a fault for not following the procedures and protocols, especially given that they were aware of the potential hazards and still failed to act on them.

Where we place the accountability for this gas leak often follows directly from who we believe is responsible for the leak in the first place. Given the frequency of industrial ‘accidents’ in India, would it be fair to place the accountability of this particular leak based on closely weighing which actor is most at fault for this isolated event? Or should this event be viewed as only the latest in a long series of industrial “accidents” occurring in India?

Certainly the government and the management could be held accountable for their negligence.

But where do we place the responsibility of opening a potentially toxic-gas-leaking plant in a residential area in the first place? Toxic chemicals like Styrene have always been a risk to the health and lives of humans and nonhumans. This, however, does not stop new plants (with inherent risks of fatal accidents) from being built in close proximities to natural communities.

The corporations and the elite classes that reap the benefits from these plants, after all, do not have to live anywhere near to these plants. The ones who are the most vulnerable to the risks of such accidents (both human and nonhumans) do not have a say in any operation of the plant. This is a classic example of ‘privatization of profits, externalization of costs and risks‘ notion upon which the current globalized, imperialist, capitalist system is based.

Corporations, by their very definitions, are created to maximize profits for their shareholders, disregarding any concerns for morality or compassion. When a corporation’s actions harm others, but maximizes its own profits, should it be blamed for acting in a way consistent with its design, or should we blame the culture that came up with this design in the first place?

In this case, the corporation failed to abide by the regulations and protocols in its jurisprudence. Even this is not a novel behavior for a corporation. In some cases, corporations have challenged, or even modified, laws of a nation.

As much as the corporation could be said to be acting in a way consistent to the rules of its creation, the same could not be said for the government. Ideally, a government should give precedence to the greater good of the (human) society over the selfishness of an individual (or in this case, a legal entity). The government failed to do so in two ways: by allowing the plant to open in the first place, and by reopening the plant without consideration of the risks involved. In both instances, economic gains were prioritized over the wellbeing of the human and natural communities.

Eventually, the burden of responsibility has fallen on the ones most vulnerable to these risks. Initially, the local people have organized protests to permanently shut the plant, after which LG Polymers began transporting 13,000 tonnes of Styrene gas back to its parent company in South Korea. Statements from authorities indicate a “revamping” of the plant. Closure of the plant seems to not have been discussed.

More recently, the demands have been modified to take a more moderate stance: including free ration for the villagers for 2 months, and that the workers previously employed on a contract basis be provided with a permanent job.

Salonika is an organizer at DGR South Asia and is based in Nepal. She believes that the needs of the natural world should trump the needs of the industrial civilization.

Featured image: Vishakhapatnam skyline by Av9, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

by DGR News Service | Jan 17, 2020 | Indigenous Autonomy

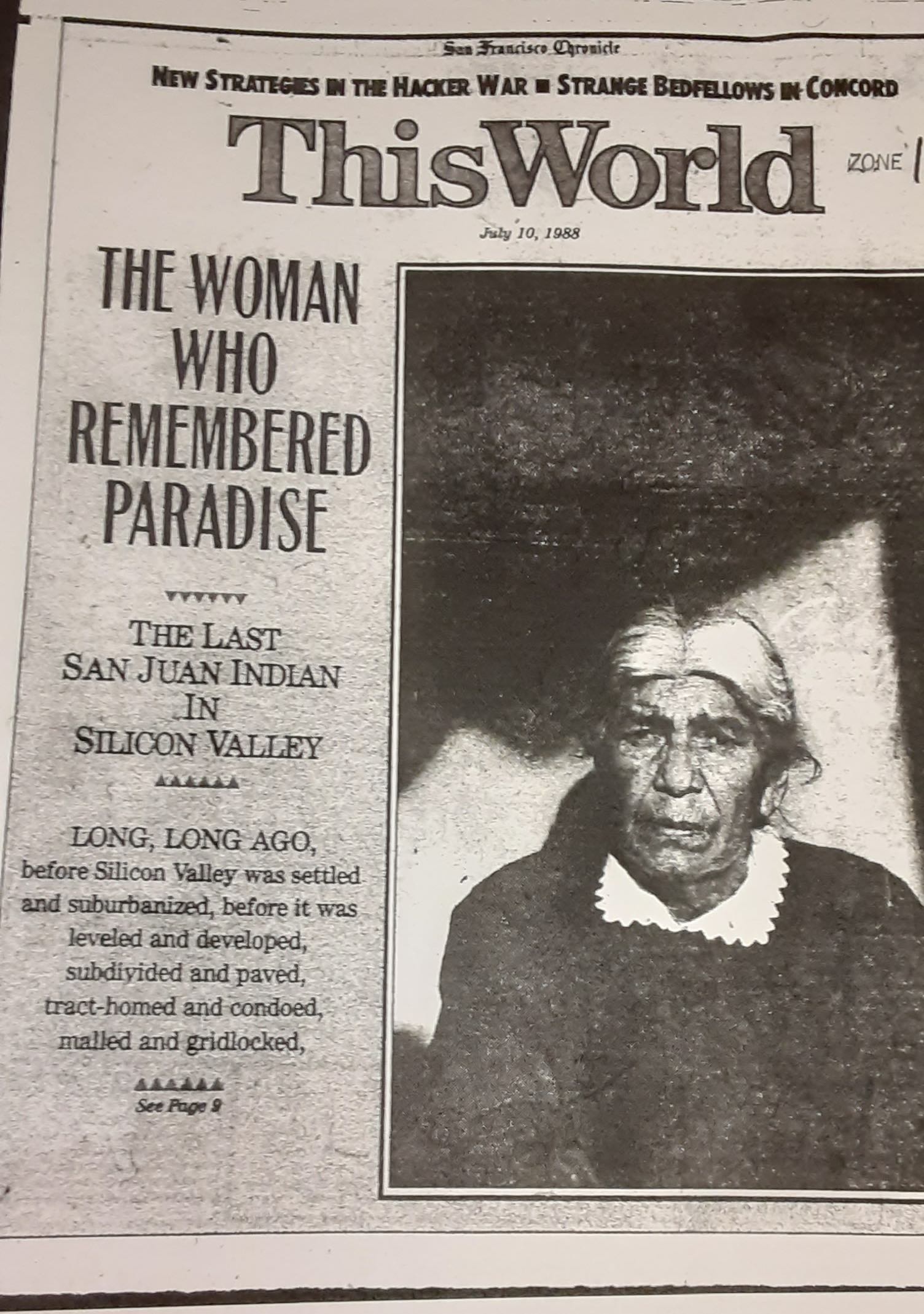

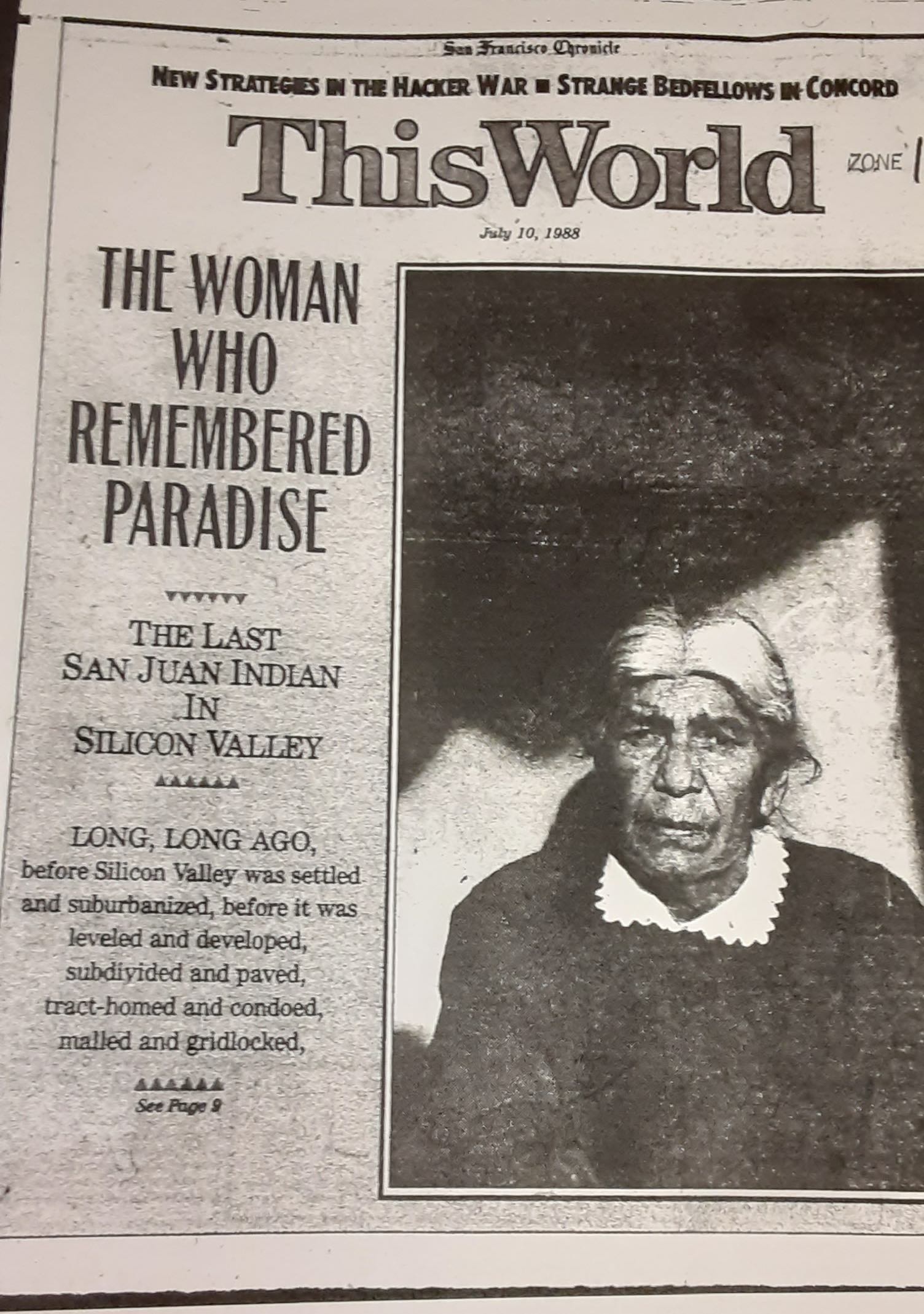

Editor’s note: The following is the complete text of Larry Engelmann’s “The Woman Who Remembered Paradise,” which first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, on July 10, 1988. The “Westerners,” whom the Spaniards called the “San Juan Indians,” are elsewhere identified as the Amah Mutsun people, who lived and hunted in what are today’s San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito Counties.

Anyone who finds this article as moving as we do is encouraged to visit the Amah Mutsun website. The tribe’s statements about themselves, their past and their future are equally educational and moving, and make it clear that while Ascención Solórsano may have been the last person fluent in the Mutsun language, the tribe itself is far from dead. Further reading has confirmed that Popeloutchom was NOT in Santa Clara Valley, but in the Pajaro River valley, around the present day town of San Juan Bautista, in San Benito County, just northeast of Monterey. At that time, the tribe’s range was roughly from there to Santa Cruz, and was the reason for the establishment of the missions at San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz.

This article does, in some ways, reflects the prejudices and simplistic understandings of anthropologists and of civilized attitudes towards the indigenous. However, it nonetheless gives valuable insight in the life of indigenous people of what is now central California. Thank you to Mark Behrend for providing this article, and for the above research.

The Last San Juan Indian in Silicon Valley

By Larry Engelmann

Long, long ago, before Silicon Valley was settled and suburbanized, before it was leveled and developed, subdivided and paved, tract-homed and condoed, malled and gridlocked, and long before the air was browned and seasoned, the streams and well waters shellacked with chemical solvents, before it was high-teched and silicon-chipped, mainframed and PC’ed, before it was airported, theme-parked and fast-fooded, before the rude snorting of the first automobile shattered the pristine silence on the narrow rutted trails that passed through miles and miles of gorgeous orchards, before Leland Stanford built his university, before the silver mines were chiseled out of the hills or the missions constructed, before Sir Francis Drake peered from the deck of the Golden Hinde at the Golden Gate, long before any European ever heard the word America, another race of people inhabited the place we call Silicon Valley. They believed they were living in an earthly paradise. They called it Popeloutchom.

The people of Popeloutchom were gentle. As gentle, it was said, as the climate and the cool breezes that slipped over the mountains to the west and whispered through the fruit trees and caressed all the living things in the valley each evening. They believed this valley was the most beautiful place in the world.

Because of that conviction they had no desire at all to travel far and look upon what must surely be lesser lands given by the gods to lesser men. In this garden of Popeloutchom, where the air was clear and the water pure and the Earth naturally fruitful and abundant, they were happy.

When the first Franciscan missionaries arrived and told the stories of their God and the Eden he had created for his first man and woman, the people of Popeloutchom were fascinated and flattered. Obviously, they felt, the God of the Franciscans had once seen this valley, and had tried to copy it for his people far away.

The important difference, of course, between his Eden and this place was that no one had ever been expelled from this paradise. Here there was no evil serpent and no fall from grace, no paradise lost. Popeloutchom was paradise preserved. In the English translation of their own language — a language long since lost — the people of Popeloutchom called themselves “the Westerners,” because they were the westernmost group of several loosely related tribes. Over the years, though, they had lost contact with their Eastern cousins, who had simply melted away, like snow before the summer sun. Yet the gods had preserved and sustained the Westerners in Popeloutchom.

The Westerners were an indigenous people, who knew neither treachery nor deceit nor war. They welcomed the befuddled strangers who sometimes stumbled upon their settlements. Such lost travelers were regarded as honored guests who would, when treated warmly, tell unusual stories about distant places and strange gods, before moving on.

And so the Westerners welcomed the first white men who “discovered” their valley. Unlike earlier travelers, however, these intruders came to stay. They constructed missions, put up walls and worshiped the God who created Eden. And they brought with them also their deadly trinity of cholera, smallpox and measles. The Westerners, with no immunity to the European diseases, began to die by the hundreds. Those few who survived were brought within the discipline of the missions. They lost their old faith and their old lands. They were given a new name by the missionairies. They became the San Juans.

And gradually, like their Eastern relatives, they melted away.

Early in the twentieth century, when historians and ethnologists tried to record the story of the Westerners, they found that those gentle people of Popeloutchom had become extinct. And they concluded, after careful research, that sometime around 1850, the last member of that kindly and tolerant race had vanished.

It came, then, as a substantial surprise when word was relayed to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., in late 1929, that all of the Westerners had not died. There remained, in fact, a single surviving full-blooded member of that tribe. And she wanted the story of her life and of her people recorded for posterity.

John Harrington, the Smithsonian’s leading ethnologist, rushed to California in order to transcribe that final testament of this rare survivor of a lost race, this last Westerner.

She called herself Ascención Solórsano, and for as long as anyone could remember, she had lived in Gilroy. There she was known, because of her curative powers, as a great and generous “doctora.” For several decades, the few remaining Indians of the region had known of the miracles performed by the doctora. Her wisdom, they believed, was the accumulation of learning of a hundred generations of Westerners.

Each day, the sick and the lame and the afflicted came to her from hundreds of miles away. They lined up in the doorway to her tiny house, and camped at night in her yard, transforming her property into a humble pastoral version of Lourdes. Inside, the doctora listened carefully to their tales of physical woe. Then she mixed tonics and ointments from local herbs and roots and dispensed them to the afflicted. It was rumored that the remedies of the doctora were always successful. She restored the health of anyone who sought her help. Those who could, paid for her miracles. Those who could not pay brought food or small articles of some value. And those who could pay with nothing material were reminded simply to remember the doctora in their prayers.

For many years the doctora tirelessly carried on her practice. The local press ignored her and the local authorities overlooked her. She practiced medicine without a license, to be sure. But those who were supposed to enforce laws forbidding such activities either never heard of her or never believed she existed. No complaints for malpractice were ever filed against the doctora.

Then, one night in the late summer of 1929, a light evening breeze whispered a prophetic message to the doctora. For all of her life, Ascención had read such portents and premonitory signs in the wind and rain, and in the lost language of the birds. She could read the messages from nature as easily as one today might read the headlines in a newspaper.

The wind told Ascención that she was going to die in three days. And so now at last the things that remained to be done must be done quickly.

She took out the black silk dress she had sewn years earlier to wear when she confronted death. She then said goodbye to her friends in Gilroy and went to the home of her daughter — who was half Indian — in Monterey. There, in her daughter’s tiny two-room frame house, she waited for death. A bed was set up in one room and several pillows were placed on it so that Ascención might sit up comfortably. Neighbors and friends were summoned to see her. And she shared with them all the stories and the collective memories of the Westerners. It was, she believed, the final gift of her lost race to the children of the despoilers of Popeloutchom.

Then, through her narrative, Ascención apparently assuaged the gods of the Westerners and aroused their compassion. As she spoke, day after day, her strength was restored and death was postponed.

When Harrington arrived from Washington, Ascención looked at him in silence for a long time. Then she pronounced her evaluation of the enthusiastic scholar. “You are a vehicle of God,” she said, “that comes to see me in the 11th hour to save my knowledge from being lost. I will teach you up to the last day that I can, and see if I can tell you all that I know.” This is what she told him.

“I have lived for 83 years. My mother, Barbara Sierra, lived for 84 years. And my father, Miguel Solórsano, lived for 82 years. One week after the death of Barbara Sierra, my father died of grief at the loss of his lifelong companion.”

Ascención, their only child, was taught the language and the legends of the Westerners by her parents. But with their deaths, the dialogue in the native tongue was relegated forever to the world of the spirits.

She said that the Westerners traced themselves back hundreds of generations to a time when men had descended from the gods and had been placed in Popeloutchom. This was followed by a great flood that caused the ocean waters to rise to the top of the Gabilan Mountains. Following the flood, the founder of the Westerners taught his children how to live on Earth, how to heal illnesses, how to prepare food, build homes and worship the gods. This father and teacher had then departed to the world of the afterlife in the west, beyond the mountains and the sea and the sunset. And there, after death, every Westerner would in his turn be welcomed by the father and teacher. Yet, after death, the Westerners might still visit their children and friends in Popeloutchom in dreams.

Among the Westerners, Ascención said, age was respected and venerated. It was not, as among the white people, considered simply a purgatory prior to death. With age, the Westerners realized, came wisdom and magical powers. Aged women, it was believed, had the power to control the growth of plants.

And death was not something that the Westerners feared. When death came, relatives of the deceased covered themselves with ashes and mourned openly. Some even removed themselves from other members of the tribe for several days and fasted and chanted songs of death.

In Popeloutchom, Ascención said, “nature provided such an abundance of food that the Westerners always had an oversupply of wild fruits, greens and seeds.” Consequently, they did not practice agriculture, nor did they ever cultivate the land. And except for the simple process of gathering food each day, work was completely unknown to the Westerners. They lived like Adam and Eve in Eden. Daily life was organized around leisure and play, and there was neither worry nor care about tomorrow.

The men and boys of the Westerners wore no clothing. And the women wore only a simple brief buckskin skirt. Yet, Ascención asserted, their skin did not burn in the summer sun, nor did they catch colds, even in the most severe winters.

The secret of their health, she believed, was the daily immersion in cold water. Each morning, as soon as they had risen from their sleep, every Westerner walked to the nearest river or stream. Even the tiniest infants were borne along. Then the Westerners jumped into the water and washed themselves. The practice was pursued every day of the year, regardless of the weather. When they left the water the Westerners returned to their dwellings for the morning meal.

The basic food of the Westerners was a gruel consisting of acorn kernels that were crushed and then bleached with water to remove the bitterness, then boiled with meat, fish or greens.

After breakfast each day, the Westerners began their daily activities. The gathering of food and fuel — the most important tasks — were considered an adventure and were carried out in both a communal and a leisurely way.

The men and boys hunted in small groups, leaving the camp each morning and returning late in the afternoon. They roamed the hillsides and the valley floor of Popeloutchom in search of game, especially deer. They were informal during the hunt, always making it more sport than work. When other local bands were sighted, the groups would stop to talk and exchange stories. If game had already been taken, part of it was cooked and eaten by both groups. Athletic competitions — running, wrestling and archery — were also common at these informal encounters.

The Western hunters had learned, through centuries of observation, the habits of their prey, Ascención recalled. They could, therefore, cover themselves with deerskin, walk on all fours like a deer, and approach their prey very closely. A small bird in flight could commonly be hit by most Western archers with a single arrow, so well did they understand the speed and flight patterns of the winged game of Popeloutchom.

In the rivers and streams of Popeloutchom, the men trapped fish in the shallows and then shot them with arrows. Sometimes, when hunting parties traveled as far as the western ocean, they took sea otter, seals and sea lions. And sometimes the hunting parties came upon a small whale that had been trapped in a tidepool or had washed ashore — a magnificent gift from the gods that might feed a single village for weeks.

While the men and boys hunted, the women and girls gathered acorns, roots, nuts, greens, fruits and other foods. In the quest for these, Ascención remembered, they blended conversation, laughter and singing. Like the men, they went out to their decidedly unstrenuous activity in small groups. Collecting firewood meant greater effort and travel, so there was seldom more than a single day’s supply of wood in any village in the valley — even when heavy rain clouds threatened.

The women also provided water for every household in a village. Water was carried from the streams in baskets woven by hand. The baskets were made from the roots of “cut grass,” and when they were filled with water they swelled and did not leak — not one drop, Ascención said.

The Westerners mastered countless crafts and passed the pride of workmanship on to each succeeding generation. The men made beautiful and powerful bows, reinforced with layers of sinew. They were master archers and could string and fire arrows with almost blinding speed. Their arrows, guided in flight by eagle feathers, slipped easily through the body of a deer or a bear.

The women were the weavers of baskets. They sat in a large circle out of doors and constructed baskets while they talked and sang. Each woman’s baskets carried a distinct design that reflected her individual creativity. The patterns were never repeated or copied. And at a woman’s death, her baskets were burned or given away to strangers.

More for sociability than protection, the Westerners lived in small villages. Each home resembled a beehive. They were constructed by driving willow poles into the ground in a circle, bending the tops together and then binding them. Horizontal poles were then laced through the verticals, and deer grass was applied as a cover. A few small holes were left as windows. The door was small and low and faced away from the prevailing winds. The ground served as the floor of the house. Sleeping mats were woven from bullrushes. Robes from deer and bear hides served as blankets.

Fifty years before Ascención was born, the first white men arrived in Popeloutchom, she said. They examined the countryside and named the land San Benito. They then built a mission and named it after a man who paid great deference to the practice of immersion in water — John the Baptist. They called the mission San Juan Bautista; the inhabitants of the 23 villages in the area near the mission were called simply San Juans, referring to their traditional practice of immersion in water. Then they taught the Westerners how to cultivate fields and work and how to pray and how to live. And how to die.

Not long after the first white men had arrived in the region, the gods of the Westerners had demonstrated their grave displeasure with the intruders. The gods, Ascención said, stamped their feet upon the valley floor and caused buildings to fall and great cracks to open in the ground. The white men, of course, were utterly terrified by the quaking of the Earth. They lived outside their homes for several days and nervously questioned the Westerners about the earthquake. But the white men remained. And in the years that followed, again and again the displeased gods of Popeloutchom pounded on the Earth in protest, but in vain. The white people poured in and disregarded the warnings.

John Harrington listened to Ascención’s tales of the Westerners and scribbled down page after page of notes. He was amazed at the comprehensiveness and vividness of her memory.

He was, however, only one of many witnesses to Ascención’s long narrative. Chairs were set up facing the bed in small, even rows, and dozens of local people came daily to sit silently for hours on end and hear this last Westerner sing and chant and whisper the ageless stories of her people one last time.

And as Ascención spoke of a world that was no more and that would never be again, she drew, day after day, untapped reserves of strength. Through October, November and December, she talked and Harrington wrote. Her audiences increased as word of the wise woman’s stories spread. And many of those she had cured traveled great distances to pay their last respects and to hear her last words.

But in January her strength suddenly started to slip away. And as the end neared, she began to hear and see the spirits of the Westerners in the room and outside the house, reminding her of stories she had not yet told and beckoning her to finish her work. As she spoke, more slowly now and almost in a whisper, she would suddenly point to someone sitting at her bedside and say, “The spirit of my father, Miguel, is sitting beside you!” Then she would speak to Miguel in a language no one in the room had ever heard before and would never hear again.

Finally, she heard the spirits of her race tapping at the door, summoning her. She had told John Harrington all she remembered of Paradise, a place once called “Popeloutchom.” Now she gazed at Harrington once more in silence for a long time. It was a sad, piteous look. But the sadness and the pity were not for herself, but for Harrington and for those of us who would read what she had whispered and he had written, and who would never ever look upon a place in this world as beautiful as her Eden, her Popeloutchom.

She closed her eyes and began very gently picking imaginary flowers from the blanket. Then, peacefully and without any struggle, she stopped breathing.

It was January 1930 when the last Westerner left Popeloutchom. The next morning some of the baskets she had woven were burned, and the others were given away to strangers.

by DGR News Service | Dec 3, 2019 | Defensive Violence, Direct Action

Photo credit: Kinessa Johnson and True Activist

Editor’s Note: DGR does not endorse Kinessa Johnson or VETPAW, and views significant parts of their work as problematic (e.g. pervasive use of nationalistic propaganda, an implicit white saviour narrative, and echoes of imperialism). However, this phenomenon is interesting and worth discussing.

by Liam Campbell

Kinessa Johnson is a heavily tattooed U.S. military veteran, she is also an experienced firearms instructor and mechanic. After completing one tour in Afghanistan she joined VETPAW, an NGO that focuses on providing training and resources for park rangers and anti-poaching groups that protect endangered species. According to Johnson, park rangers in Africa face extreme danger “they lost about 187 guys last year over trying to save rhinos and elephants.” VETPAW’s response is to send U.S. combat veterans to provide specialist training, in hopes that they can help park rangers reduce both poaching and their own casualties.

Framing their mission.

According to Johnson “after the first obvious priority of enforcing existing poaching laws, educating the locals on protecting their country’s natural resources is most important overall.” Although this perspective has an implicitly patronising tone, there is also some validity in it — park rangers are often under resourced, which results in poor training and inadequate equipment. Sending rangers highly-trained specialists makes sense, as does sending them better equipment. What gives me pause about a group like VETPAW is how they’ve framed their mission:

“VETPAW is a group of post 9/11 US veterans with combat skills who are committed to protecting and training Park Rangers to combat poaching on the ground in Africa.

We employ veterans to help fight the increasing unemployment rate of this group in the US but also, and most importantly, because their skills learned on the frontlines in Afghanistan is unrivaled. These highly trained service men and women lead the war against brutality and oppression, for both human beings and the animal kingdom.”

Problematic language.

What stands out to me is the combination of nationalistic buzzwords and the patronising framing. Why specify “post 9/11 US veterans?” Because those are all trigger words for American nationalism. It’s also problematic that their mission frames U.S. veterans as champions who opposed “brutality and oppression.” Last, but not least, is their use of the phrase “animal kingdom” which is a subconscious frame implying an inherent hierarchy (where, presumably, either humans or a christian god presides at the top).

Ecofascism.

To me, this phenomenon is reminiscent of proto ecofascism, the first seed of a new form of fascist movement that wraps itself in nationalistic flags and hides behind the morality of environmentalism. It’s also concerning that groups like VETPAW would have an obvious appeal to combat veterans who are interested in hunting economically desperate Africans, under the guise of charity.

Deep Green Perspective.

From the a Deep Green Resistance analysis perspective, this is a complex issue. It would obviously be better to quietly and respectfully provide resources to indigenously-led groups but, on the other hand, if organisations like this end up resulting in tangible reductions in poaching, that may be better than nothing. What do you think about this issue?

Let us know in the comments.

Join the Resistance

Deep Green Resistance is a political movement for liberation and revolution. We aim for nothing less than total liberation from extractive economics, white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, industrialism, and the culture of empire that we call civilization. This is a war for survival, and we’re losing. We aim to turn the tide. We mean to win.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 17, 2019 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The collusion between officials and poachers was exposed in India’s Down to Earth magazine. © Down to Earth

by Survival International

Park officials in India’s Rajaji Tiger Reserve colluded with poachers in the killing of endangered leopards, tigers and pangolin, according to an investigation by a senior wildlife officer.

The accused officials range from the park director to junior guards. WWF-India boasts that it trained “all Rajaji frontline staff in skills that were vital for protection,” including law-enforcement. It also provided vehicles, uniforms and essential anti-poaching equipment to the guards.

The investigation, reported in India’s Down to Earth magazine, found that not only were officials helping to hunt down and kill wildlife, they also beat and tortured a man named Amit – an innocent villager who was trying to stop the poaching.

Officials are reported to have arrested Amit under false charges, resulting in him being detained for up to a month. He was also beaten and given electric shocks by a wildlife warden and two range officers.

These revelations of serious human rights abuses by guards trained and supported by WWF follow the recent Buzzfeed exposés that WWF funds guards who kill and torture people.

The involvement of those supposed to protect wildlife in hunting is common. A UN report in 2016 confirmed that corrupt officials are at the heart of wildlife crime in many parts of the world, rather than tribal peoples who hunt to feed their families.

Stephen Corry, Survival International’s Director, said today: “Rangers who poach as well as violate human rights won’t surprise those environmentalists who’ve been speaking against fortress conservation for years. Corrupt rangers often collude with poachers, while tribal people, the best conservationists, bear the brunt of conservation abuses.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the New Park City Witness index to read more.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

In Park City, the task is clear: Stop climate change, or the snow stops. Snowpack is the region’s freshwater supply and water is life. So, stop climate change or the community will lose life.

This is not news to most Parkites. And, thankfully, many Parkites have taken, at least, some kind of action. Park City Municipal Corporation hopes to achieve carbon neutrality, for the whole community, by 2032. An electric bike program was recently introduced, and electric city busses now run routes through town, in an effort to reduce carbon emissions. In a truly amazing display of community generosity, $38 million was raised to protect Bonanza Flats from development.

Meanwhile, there are a growing number of us in Park City, and across the country, who have lost faith in the traditional tactics employed by the environmental movement for creating change.

We voted. Many of us helped Barack Obama gain the presidency only to see American natural gas production increase by 34% and crude oil production increase by 88% since George W. Bush’s final year in office. Our votes couldn’t stop Donald Trump from gaining the presidency and everyday brings more news of his insanity. The EPA is gutted. The United States pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord. And, climate change deniers occupy many of the federal government’s most powerful positions.

We reduced, reused, and recycled. Then, we learned that the general consensus amongst climate scientists is that developed nations must reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% below 1990 levels by 2050 to avoid runaway climate change. While it was still funded, the EPA reported that small businesses and homes accounted for 12% of total US greenhouse gas emissions while personal vehicles accounted for less than 26% of total US emissions. Based on these numbers, we realized that even if every small business and home in America reduced its emissions to zero and each American drove cars that emitted no greenhouse gas, the United States wouldn’t even come close to that 80% goal.

We participated in traditional conservation efforts. We helped to save Bonanza Flats from the bulldozers and chainsaws. But, we have not yet saved Bonanza Flats from the droughts, the wildfires, the fungus-killing aspens, and the pine beetles all made worse by climate change.

We are ready for escalation. We are ready for direct action.

**

Beneath the positivity, the small victories, and the feel-good atmosphere characterizing life in a mountain town like Park City, a desperation quietly grows. Climate change worsens, mass extinction intensifies, and natural communities collapse. Parents and grandparents fear for the futures of their children and grandchildren. Older generations approach the end of their lives worrying that they failed the younger generations. Younger generations wonder if they truly are disempowered, or if disempowerment is an illusion ensured by the apathy they’ve been labelled with.

For the most part, the desperation remains unacknowledged, unnamed, and repressed. Removed from the violence producing our material comforts and granting us the ability to live in a place like Park City, many never feel the desperation. Those who do doubt the authenticity of their intuition and wonder if the desperation is a sign of mental illness, proof that something is wrong with them, or a character flaw. When the desperation is expressed, those who point it out are called alarmists, conspiracy theorists, and sensationalists. When the reality described is too obvious to ignore, those who describe it are accused of causing paralysis and depression.

Nevertheless, the planet’s health is critically threatened. And, things are getting worse. We must act urgently and decisively. For those of us who know this, the question becomes, “How do we encourage others to act with the necessary urgency and decisiveness?”

***

In 2012, the Summit Land Conservancy published the second edition of Park City Witness: A Collection of Essays and Artwork Celebrating Open Space. In her introduction, Cheryl Fox – Executive Director of the Summit Land Conservancy – wrote, “Today we face unprecedented challenges to our natural environment. Solving this problem is the moral challenge of our century. The question we must ask is not ‘what can I do?’ but ‘what is the right thing to do?’”

I completely agree with her. Several months before I read her words, I wrote in my essay “Park City is Still Damned,” “Don’t ask, ‘What can I do?’ Instead ask, ‘What needs to be done?’”

So, what is the right thing to do? What needs to be done? Ms. Fox concluded her introduction with, “I encourage you to read this book. Then go out to the trails, the mountains, the creek that you have helped to save. Watch for angels or demons and the messages they send, and then bear witness…”

It’s been five years since Summit Land Conservancy published its celebration of open space in Park City Witness. In that time, the list of the indicators of ecological collapse has only grown longer. Witnesses, testifying in court, take an oath to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. There are angels on the trails, the mountains, and in the creeks. But, there are demons, too. If we only bear witness to beauty, to optimism, and to celebration, we are liars. Telling the whole truth demands that we confront the demons, no matter how horrifying they are.

I have devoted my writing career to two principles: The land speaks. And, I have a responsibility to communicate what the land says as best I can. I hear the land speak of beauty. I also hear the land speak of horror. In Park City, while most writers and most artists focus on stories of beauty, who will confront the stories of horror?

We need new Park City witnesses. I cannot ask anyone to do what I myself am not willing to do. So, I commit, publicly, to being a new Park City witness. One who lives as honestly as possible with two realities. There is beauty and there is horror. The horror will consume the beauty if it is not confronted, described, and resisted.

To give my commitment substance, I have acquired a reliable vehicle, spent weeks researching, cleared my schedule, and formed a plan to visit places in Park City and across Utah where horror threatens to overwhelm beauty. These are places like the planned site for the Treasure Hill development, the Uintah Basin, oil refineries in North Salt Lake, the White Mesa uranium mill, and the coal mines in Price. My experiences will form a place-based series. Each essay will grow organically from the natural community it is written from. I welcome community discussion, comments, and feedback. The Deep Green Resistance News Service has graciously agreed to publish the writing this journey produces and you can follow along here. Please feel free to contact me.

My purpose is simple: In each place, I will search for beauty and I will search for horror. Then I will ask of that place, “What do you need?” I will listen for as long as I need to, knowing that the land rarely speaks in English and rarely observes a time recognizable by common human patience. After this, I will write. I will write as honestly as possible.

I hope to give a voice to those who feel the desperation. I hope to comfort those who feel crazy for the intensity of their concern. I hope to demonstrate that their concern is justified. I hope to catalyze the courage we so desperately need to resist effectively.

I hope to be a new Park City witness.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org