Des Moines, IA – Ruby Montoya, admitted Dakota Access Pipeline ecosaboteur, stepped out of a car Wednesday morning in front of the federal courthouse in Des Moines, Iowa, and walked quietly into the building. Her dark hair was pulled back into a low bun and her long, teal skirt blew in the wind. Her attorney, Maria Borbón, walked behind her.

The atmosphere outside the courthouse that morning was mundane, lacking the usual fanfare of a high-profile political sentencing. No family, friends, or supporters were present for the two-day hearing, which brought to close a legal battle spanning almost exactly three years to the day. Montoya was ordered to spend the next 72 months of her life in federal prison—a sentence imposed for her fierce participation in the protest movement against the pipeline project, which at its height attracted tens of thousands to the icy plains of rural North Dakota.

Montoya was also ordered to pay over $3 million in restitution to Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), the multi-billion dollar fossil fuel transport corporation primarily responsible for the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, known as DAPL. She was ordered to pay the restitution jointly with her co-defendant Jessica Reznicek.

From her elevated platform, U.S. District Judge Rebecca Ebinger looked down on Montoya as she read aloud her sentence Thursday, stating in part that a long prison sentence was necessary to deter others from taking similar action. When the hearing was over, the judge nodded to the U.S. Marshals waiting in the back of the courtroom; they then approached Montoya and handcuffed her before leading her away.

It was a lonely end to Montoya’s yearslong journey from Mississippi Stand, the Iowa anti-pipeline encampment where she and Reznicek first met, to the most elaborate and successful campaign of sabotage to arise out of the No DAPL movement.

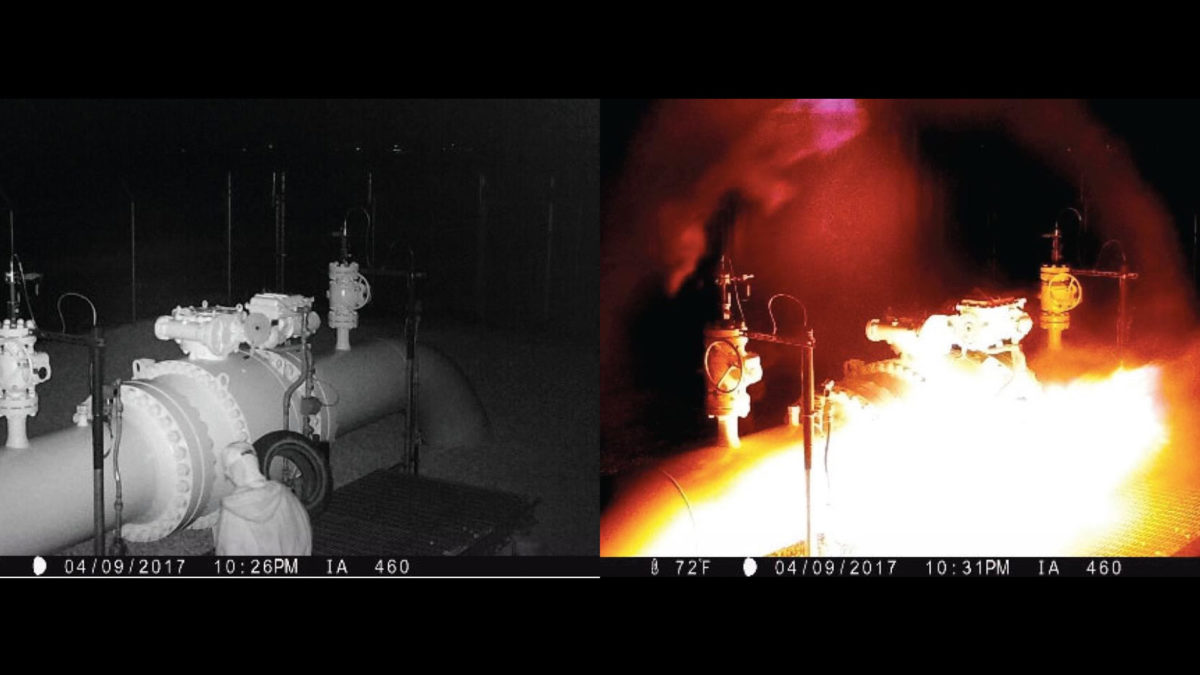

Between November 2016 and May 2017, Montoya and Reznicek attacked DAPL infrastructure in at least 10 locations, setting fire to construction equipment and using oxy-acetylene torches to cut holes in the pipeline’s steel walls. Prosecutors also alleged in court filings that two earlier acts of sabotage, for which the pair were not charged, matched the profile of their later actions.

According to the pipeline company, the attacks resulted not only in the $3,198,512.70 in damages Montoya and Reznicek were ordered to jointly pay in restitution, but cost ETP an additional $20 million in added security expenses as well.

In a dramatic press conference in July 2017, the two admitted to their direct action campaign before turning around and prying the letters off the sign in front of the Iowa Utilities Board Office of Consumer Advocacy, expressing no remorse for their actions. “If we have any regrets, it is that we did not act enough,”they wrote in a public statement at the time.

In June 2021, Reznicek was sentenced to eight years in prison, a term that included a domestic terrorism enhancement. Reznicek later appealed the enhancement, but it was upheld on June 6, 2022 by judges Ralph R. Erickson, David R. Stras, and Jonathan Kobes, on the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. (All three judges were appointed by former president Donald Trump.)

The course of Montoya’s three-year grind through the federal court system took many turns. She went through four attorneys and went from cooperating with her co-defendant to cooperating with law enforcement. During this legal process, she and Reznicek were labeled terrorists by the government, an highly political accusation that dramatically increased their possible prison sentences and created increased repression on environmental movements across the country.

A “Harmless” Terrorism Enhancement

In October 2017, less than three months after Montoya and Reznicek’s public confession, a group of 84 members of Congress wrote a letter to then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions, asking the Department of Justice to consider whether 18 U.S.C. 2331(5), the federal criminal code governing domestic terrorism charges, applied to acts of sabotage committed against the DAPL project.

The application of terrorism enhancements at sentencing can add a decade or more to a defendant’s sentence, and the decision to apply them is highly politically charged. According to the federal statute, crimes can be considered “domestic terrorism” if they “involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State” and are “calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct.”

There is a longstanding precedent for terrorism enhancements being used against animal rights and environmental activists. According to a 2019 study by The Intercept, of the 70 federal prosecutions of animal and environmental activists they identified, the government sought terrorism enhancements in 20. Those cases include 12 of the defendants in Operation Backfire, the major FBI operation that targeted the Earth Liberation Front, also known as ELF.

However, it’s also notable when terrorism enhancements are not applied. As many have pointed out, participants in the January 6th Insurrection have not received terrorism enhancements, despite participating in a political attack on the heart of the U.S. government, an event which led to several deaths. Neither Dylan Roof, the white supremacist who murdered nine African Americans in 2015, nor James Fields, the neo-Nazi who intentionally drove his car into a crowd in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing Heather Heyer and injuring 35 others, received terrorism enhancements.

In Montoya’s case, Judge Ebinger calculated that according to federal sentencing guidelines Montoya’s sentence would have been 46-57 months without a terrorism enhancement. The terrorism enhancement elevated her sentencing range to 292-365 months—a possible sentence of 24 to 30 years in prison.

In November 2021, Reznicek appealed her case, arguing that the lower court had erred in applying the terrorism enhancement for several reasons. Reznicek’s actions, her attorneys argued, did not constitute terrorism in part because they did not primarily target government conduct. The pair’s public statements “decried perceived failures of the government but did not make express or implied threats and did not articulate any hoped-for effect of the offense on government conduct,” Reznicek’s attorneys wrote in the appeal. “The only purpose articulated in the statement was to ‘[get] this pipeline stopped,’” they continued.

The court of appeals upheld Reznicek’s conviction and the application of the terrorism enhancement, claiming that it was “harmless” because Judge Ebinger would have sentenced Reznicek to 96 months in prison regardless of the enhancement.

During Montoya’s sentencing hearing, the prosecutor seemed to anticipate the same arguments raised in Rezniceck’s appeal, arguing that Montoya’s actions were clearly intended as retaliation for the government’s approval of the DAPL project and to influence its decisions about the project’s future.

Maria Borbón, Montoya’s attorney, seemed ill-suited to the task of countering these arguments as well as many other arguments made by the prosecution during the two-day hearing. Her courtroom conduct frequently appeared to frustrate the judge, who repeatedly lectured her on procedural norms of federal court. When asked to speak, her comments were often off topic and occasionally incoherent.

Federal judges have discretion to deviate from sentencing calculations, and in Montoya’s case, Judge Ebinger explained that she decided to depart downward from the possible 24 years allowable under the guideline calculation. Her consideration included Montoya’s mental health and extensive history of childhood trauma, her good behavior on pretrial release, and her efforts to assist the government through four “proffer” interviews in 2021 (the contents of which remain sealed).

Violent Extremism Research Center Director Claims Iowa Catholic Workers Further “Terrorist Ideology”

At sentencing, the defense called Dr. Anne Speckhard, Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE), who claimed that Montoya had been manipulated by what she called the “terrorist ideology” of the Des Moines Catholic Worker and the environmental direct action movements she’d been a part of.

The Catholic Worker movement was founded in 1933 by anarchist journalist Dorothy Day and French-born Catholic social activist Peter Maurin. The movement, which is ongoing, focuses on redistributing wealth and resources through food pantries and shared housing, and uniting workers and intellectuals through educational discussions and joint activities.

While Speckhard testified in Montoya’s defense, claiming she had little to no responsibility for the actions she took while in a “dissociated state,” her testimony also insinuated that the actions taken by Montoya and Reznicek amounted to terrorism. She referred to the Des Moines Catholic Worker as “cult-like” and claimed that Montoya had been “recruited” and “elevated” by Reznicek who preyed upon her weakness.

According to its website, ICSVE was founded in 2015 and works closely with both domestic government agencies like the Department of Homeland Security as well as military organizations like NATO.

ICSVE is one of several organizations and governmental bodies that promote an approach to domestic terrorism called “Countering Violent Extremism”(CVE). According to the nonpartisan think tank Brennan Center for Justice, CVE are a “destructive counterterrorism program” that is “bad policy.” The think tank also explains that CVE are “based on junk science, have proven to be ineffective, discriminatory, and divisive.”

After the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Justice named Boston as a CVE pilot program site in 2014, the ACLU of Massachusetts “raised serious concerns about the civil rights, civil liberties, and public safety implications of adopting this unproven and seemingly discriminatory approach to law enforcement.” Unicorn Riot spoke with an ex-FBI agent, Mike German, from the Brennan Center about CVE in 2017.

CVE originated in the United Kingdom as Preventing Violent Extremism or Prevent, which “led to repeated instances of innocent people ensnared, monitored, and stigmatized,” including a nine-year-old boy who was “referred to authorities for ‘deprogramming’ purposes,” according to the ACLU of Massachusetts. In 2016, Unicorn Riot covered a CVE panel in Minneapolis hosted by the Young Muslim Collective, a panel about resisting surveillance in 2017, and another in Boston in January 2018.

“She was not the one who struck the matches”

Since August 2021, activists and legal professionals have raised concerns that Montoya may have begun cooperating with law enforcement in an attempt to reduce her prison sentence by putting other activists at risk of prison instead.

In her August 2021 motion to withdraw her previous guilty plea, Montoya publicly cast blame on a slew of people and claimed she lacked the mens rea—the intention or knowledge of wrongdoing—to understand what she was doing. Montoya argued that her abusive father, her “coercive” co-defendant Reznicek, the Des Moines Catholic Worker, and possible undercover “government operative[s]” were each in part responsible for her actions.

In the months that followed, Montoya’s new attorney Daphne Silverman filed a series of sealed documents with the court, the contents of which are still unknown to the public. Filing sealed documents is a practice usually avoided by participants in political movements as it can raise suspicion within activist communities that a defendant may be attempting to cast blame elsewhere by informing on other activists.

Montoya and her attorneys have also continued to pursue the argument that some sort of government or private security operatives “influenced me” and “appear to be unlawfully pressuring me to engage in illegal acts,” as Montoya put it in a November 2021 affidavit to the court. The affidavit goes on to discuss three unnamed people Montoya says influenced her to use fire to damage construction equipment and even taught her how to weld.

According to Montoya, she and Reznicek traveled to Denver where the unnamed people taught them to use an oxy-acetylene torch and encouraged them to do so. “Inside Person 2’s house,” in Denver, Montoya wrote, “there were army training manuals of how to destroy infrastructure, and little else. They slept on sheepskin.”

In Montoya and Reznicek’s previous public statements, the pair claimed that they acted in secret without the knowledge or involvement of other activists. “It’s insulting on some level,” Reznicek said in a 2017 joint interview with Montoya, “but it needs to be cleared up. Ruby and I acted solely alone. Nobody else was involved in any of these actions. I think it’s hard for people to believe ― ‘How could these two women pull this off so easily?’”

Montoya’s testimony is the only evidence on record suggesting that the individuals she claims taught her to weld actually exist. If, indeed, they do exist, it is unclear whether they are actually government operatives or activists who believe in using direct action against the fossil fuel industry.

At sentencing, the federal prosecutor spoke of these assertions as though they were ridiculous, calling them “conspiracy theories” and even sought to increase Montoya’s prison sentence as a result of her implicating the government in her actions.

The historical record reveals that government operatives and informants, especially those employed by the FBI, pressuring activists into property destruction and even providing them the means to do so may be a conspiracy, but is much more than a theory. The fairly recent cases of Eric McDavid, in which a government informant concocted and lured him into a bomb plot and the Cleveland 4, in which a paid FBI informant sold fake C4 explosives to a group of young Occupy activists while also providing them drugs and resources, clearly document this reality. The history of FBI surveillance and entrapment of Muslim communities is even more extensive.

At sentencing, Montoya’s fourth attorney, Maria Borbón, argued that the courtroom should be closed during sentencing, referring to the “sensitive nature” of some of the topics discussed. The judge denied her request, saying that the public record in this case had already been “oversealed” in a manner that is “contrary to the public interest.”

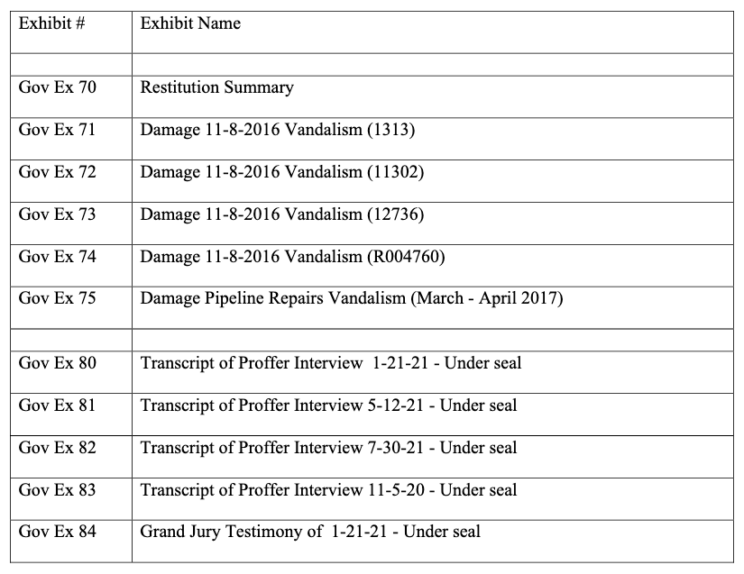

On the morning of the first day of sentencing, federal prosecutors filed an unsealed document containing a list of more than 80 exhibits they intended to use at the hearing that day. Most of the items on the list are public statements made by Montoya about her actions as well as assessments and images of the damage her and Reznicek caused to fossil fuel infrastructure. At the end of the list, as seen below, are five exhibits titled Transcript of Proffer Interview and Grand Jury Testimony dated from November 2020 to July 2021.

Although transcripts of these interviews remain sealed, their contents were briefly mentioned by the attorneys throughout the proceedings, including a claim by Montoya that at one point she threw away $5,000 in cash in an effort to stop Reznicek from continuing the sabotage campaign. This claim was part of a relentless attempt by Montoya and her attorneys to deflect blame for her actions onto her co-defendant and the Des Moines Catholic Worker House, especially its founder and de facto leader, former priest Frank Cordero.

“At no time did Ms. Montoya lead,” said Borbón. She claimed instead that Montoya’s actions were “directed by the household,” referring to the Des Moines Catholic Worker House. “She remained in the vehicle,” Borbón explained when arguing Montoya’s alleged lack of participation.

“She was not the one who struck the matches, she was not the one who put together the funds to continue the vandalism.”

Maria Borbón, Montoya’s attorney

However, according to the federal prosecutor, Montoya said in her proffer interview that she was the one who lit the match during their election night attack on construction equipment in Buena Vista County, Iowa. The prosecutor also said that in those interviews, Montoya says that she, not Reznicek, was the author of the pair’s 2017 public statement claiming responsibility for the attacks.

The government’s exhibit list also contains a listing for a document titled Grand Jury Testimony of 1-21-21- Under seal. It was not previously known to the public that Montoya had testified before a federal grand jury, and the reason it was convened remains shrouded in mystery.

“Misguided, wrong and lawless”

In her closing statements, Judge Ebinger identified “three versions” of the events of 2016 and 2017, each as told by Montoya at different points in time. The first is the story she told during her public confession and in the pair’s public talk at the Iowa City Public Library in August 2017. In this version, the judge said, Montoya appeared as “an educated woman who speaks articulately” and “passionately” about the value of property destruction in furthering the aims of the environmental movement.

“I have a choice,” said Judge Ebinger as she quoted Montoya’s description of why she joined the No DAPL protests, “I knew I had to go there. And so I hit the road.”

The second version is the story told by Montoya in the proffer interviews with the government, in which she knew the facts of each attack and could recite them in great detail to the willing ears of law enforcement. In this version, Montoya said that she had limited contact with Des Moines Catholic Worker Frank Cordero, hearing his thoughts mostly from Reznicek.

The third version is the story told by Montoya to her mental health providers, which they relayed in court during the sentencing. In this version, Montoya is a deeply traumatized and mentally ill person who was “coached” and “manipulated” into taking action by Cordero and Reznicek. According to Montoya’s care providers, she suffers from such severe post-traumatic stress disorder that she committed her crimes “in a fog” and in a “dreamlike” and “childlike state” of dissociation that she hardly remembers them.

The Montoya represented in the third version of her story is deeply sorry for her actions and it was this Montoya who addressed the court during allocution, the defendant’s formal statement prior to sentencing.

“I am here to take responsibility for my actions,” Montoya told the court, “which were misguided, wrong and lawless.” Nonetheless, she said through tears, she was on a “journey of self-accountability” which included her attempts to “rectify” her actions through her “statements to the government and my grand jury testimony.”

Despite her pleas, it was primarily toward the Montoya represented in version number one that Judge Ebinger directed her sentence, saying that Montoya’s statements during “the conspiracy period” were entirely “inconsistent with someone who is in a fog or a dreamlike state.” The judge quoted repeatedly from Montoya’s public statements, arguing that she was cogent, articulate and proud of her actions.

Nonetheless, the judge said, “the court recognizes and credits the adverse childhood experiences” testified to by Montoya, her mental health providers, and several family members. “PTSD frequently rears its head in this courtroom,” Judge Ebinger said.

In recognition of these challenges, she recommended that the Bureau of Prisons designate Montoya to a facility in or close to Arizona and that she be allowed to participate in any available vocational trainings during her six years of life in a prison cell.