Carter Dillard is the policy adviser for the Fair Start Movement. He served as an Honors Program attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice and also served with a national security law agency before developing a comprehensive account of reforming family planning for the Yale Human Rights and Development Law Journal.

Coastal Restoration: Saving Sand

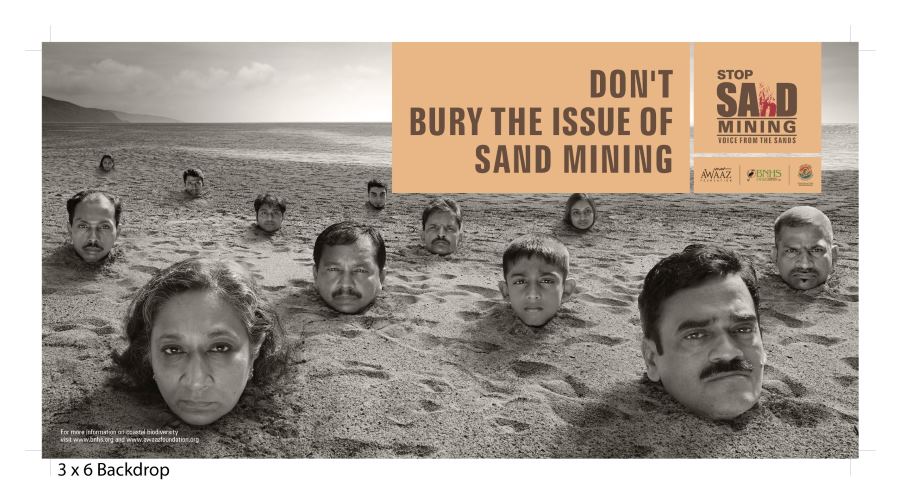

Editor’s note: It’s a coast – not a beach, we forget that when our society talks about going to the beach. A beach is for basking in the sun, getting a drink, and dabbling in the water. But a coast is far more than an entertainment place for humans, it’s a habitat for a variety of animals and plants. Sand mining is a threat to these ecosystems and criminals operate it illegally. Construction companies need sand for their concrete as the demand for buildings soars. They seal the planet by destroying coastlines – and beaches.

While beaches are being stolen in poor places, they are being nourished(replenished) in wealthy places. Beach nourishment is the process of placing additional sediment on a beach or in the nearshore. A wider and higher beach can provide storm protection for coastal structures. Sediment is commonly dredged offshore and pumped directly onto the beach, dumped nearshore by a hopper dredge, or occasionally sourced from an inland location. It is an exercise in futility that destroys natural ecosystems and subsidizes wealthy beachfront homeowners at taxpayers’ expense, particularly as worsening storms resulting from climate change demand investment in more permanent solutions to beach erosion. The sea level will rise and people living there will have to move.

It is time to stop building infrastructure and trying to control nature.

By Melissa Gaskill/The Revelator

Increasing demand for this seemingly abundant and common material harms human and natural communities — and fuels a lucrative and dangerous illegal industry.

Coastal ecosystems — including oyster reefs, sandy beaches, mangrove forests and seagrass beds — provide important habitat for marine life and food and recreation for people. They also protect shorelines from waves and storms. But these precious systems face serious threats. This article looks at what put them at risk, along with examples of efforts to restore and protect important coastal ecosystems around the world.

We need to talk about sand

Most people don’t realize that these humble grains — that ubiquitous stuff of vacations, ant farms and hourglasses — are the second-most used natural resource in the world after water. According to a 2019 report from the United Nations Environment Programme, we use more than 55 billion tons of it per year — nearly 40 pounds per person per day.

And a lot of that sand comes from illegal activity, involving criminal gangs who mine, smuggle, and kill for the precious material.

The Building Blocks of Modern Society

Sand — legal or otherwise — gets used to enhance beaches, extract petroleum through hydraulic fracking, fill land under buildings, and make computer chips.

But the biggest amount by far — an estimated 85% of the sand mined globally — goes into making concrete. Concrete combines two key ingredients: cement, a binding agent made from calcium or other substances, and aggregate, which is either sand or a combination of sand and gravel. Quality concrete requires jagged and angular aggregate grains — a quality found in only a tiny fraction of the worlds’ sand, most of it on beaches and in rivers. This sand also is easy and cheap to mine, and it’s located close to much of the construction taking place around the world.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, world consumption of aggregate for all uses exceeds 40 billion metric tons (44 billion U.S. tons) a year — an estimate that’s likely on the conservative side and represents about twice the amount of sediment carried annually by all the world’s rivers. (Sediment from land rocks is the source of most coastal sand, which also comes from shells and marine organisms pulverized by waves, the digestive tracts of coral-eating fish, and the remains of tiny creatures called foraminifera.)

Not surprisingly, UNEP calls management of sand one of the greatest sustainability challenges of the 21st century.

The organization also warns about sand mining’s serious consequences for humans and the natural environment.

Removing beach sand leaves coastal structures more vulnerable to erosion even as climate change raises sea levels and makes storms more intense. Transporting sand generates carbon dioxide emissions. Sand mining has political and cultural consequences, including effects on the tourism industry, and creates noise and air pollution.

Coastal sand mining also destroys complex ecosystems. The microorganisms, crabs, and clams that live in beach sand are important food sources for birds. Sea turtles and several bird species nest on sandy beaches. Seagrass, an important food source and habitat for marine residents, needs sandy ocean floor to grow. Stretches of underwater sand provide habitat for sea stars, sea cucumbers, conchs, and other critters, and are feeding grounds for flounder, rays, fish, and sharks.

Removing sand also affects water quality in the ocean and depletes groundwater.

Stolen Sand

Yet this harm is not the only issue. Increasing demand for sand has created a vast illegal industry resembling the organized criminal drug trade, including the same violence, black markets, and piles of money — an estimated $200 to $350 billion a year. Of all the sand extracted globally every year, only about 15 billion metric tons are legally traded, according to a report from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

Pascal Pedruzzi, director of UNEP’s Global Resource Information Database-Geneva, became aware of illegal sand mining when the Jamaican government asked UNEP in 2014 to find out why the island had a serious beach erosion problem.

“There was a lot we didn’t know about sand extraction, including how much was being taken,” he says.

Or from how many places: Sand is mined from coastal environments in at least 80 countries on six continents, according to the 2022 book Vanishing Sands, written by several geologists and other experts on coastal management and land rights.

The book outlines a litany of sand crimes, from seemingly small to massive. In Sardinia, Italy, airport officials have seized about 10 tons of sand over 10 years, much of it carried in thousands of individual half-quart bottles. In Morocco, criminals removed as many as 200 dump trucks of sand a day from massive dunes lining the Atlantic coast.

According to Africa’s Institute for Security Studies, illegal sand mining in Morocco is run by a syndicate second in size only to the country’s drug mafia. It involves corrupt government and law enforcement officials and foreign companies. Much of the Moroccan sand, for example, ends up in buildings in Spain.

In India demand for sand tripled from 2000 to 2017, creating a market worth 150 billion rupees, just over $2 billion. Multiple diverse and competing “sand mafias” run mining sites surrounded by armed private security guards. Their weapons likely are obtained illegally, given the difficult process of acquiring guns legally in India.

Photo by Sumaira Abdulali – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

The NGO South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People reports hundreds of deaths and injuries related to illegal sand mining in India each year, including citizens (adults and children), journalists, activists, government officials, and law enforcement.

There are similar stories in Bangladesh, Cambodia, elsewhere in Africa, and in the Caribbean — almost everywhere sandy coastal areas can be found.

How to Solve the Problem

UNEP has begun tackling the problem of sand mining, putting forth ten recommendations that include creating international standards for extracting sand from the marine environment, reducing the use of sand by using substitutes, and recycling products made with sand.

While these recommendations target legal sand mining, more responsible management and reduced overall demand also should make illegal mining less lucrative and, therefore, less common.

“The good news is there’s a long list of solutions,” says Peduzzi. “We start by stopping the waste of sand. We can make the life of buildings longer, by retrofitting them instead of knocking them down. Maybe change the use of a building over time, as a school first and then 50 years later, a place for elderly people. When a building needs to be destroyed, crush and reuse the concrete. Build with wood, bricks, adobe, and straw.”

Building with straw also could reduce burning of crop waste. Every year, India produces 500 million tons of straw but burns 140 million tons as “excess.” One company there, Strawcture Eco, is using straw to create wall and ceiling panels that are fire resistant, insulating, and sustainable.

Alternatives to sand in concrete include ash from waste incineration and aluminum smelting waste. Peduzzi notes that ash creates concrete that is about 10% less solid, but points out, “that is still pretty good. You can use it to make buildings, but maybe not a bridge.”

The UNEP report notes that involvement from industry, the private sector, and civil society is vital in solving the problem. For example, shifting away from building with concrete will require changing the way architects and engineers are trained, acceptance by building owners, and new laws and regulations.

“We rely on sand, as a commodity,” Peduzzi says. “But we also need to realize its ecosystem services. We must be wiser about how we use it.”

UNEP hopes to collect solutions into a single, accessible online location (although it currently lacks funding for the effort). The idea is to create a hub for policies and technological solutions, Peduzzi says, and to develop best practices for them. The Global Initiative report on India also calls for a website for tracking illegal sand mining hosted by a think-tank or journalism agency — a sort of crime-spotters portal where people could anonymously upload evidence.

Shifting Sands, Shifting Thinking

William Neal, an emeritus professor at Grand Valley State University in Michigan and one of the authors of Vanishing Sands, suggests in an email that finding sand substitutes is not enough. Coastal communities, he says, need to retreat from rising seas rather than build more hard structures such as seawalls. This “shoreline engineering” often destroys the very beaches it is intended to save, he explains, and the long-term cost of saving property through engineering often ends up exceeding the value of the property. Seawalls also tend to simply shift water elsewhere, potentially causing flooding and significant damage along other parts of the shoreline.

Peduzzi also espouses shifts in thinking, including how we get around in cities.

“Instead of building roads for cars, build subways,” he says. “That moves people faster and gets away from fossil fuels. The icing on the cake is that when digging subway tunnels, you are getting rocks, generating this material instead of using it. Cars are not sustainable — not the material to make a car itself or the roads and parking lots.”

Without systemic changes, the problem of sand removal is only going to grow bigger as the population increases and people continue to migrate from rural to urban areas, increasing the demand for infrastructure like roads and buildings.

“The problem has been overlooked,” Peduzzi warns. “People need to realize that sand is just another story of how dependent we are on natural resources for development.”

The Revelator is an initiative of the Center for Biological Diversity.

Title photo: Calistemon/Wikimedia Commons CC-BY-SA-4.0