by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 4, 2013 | Strategy & Analysis, The Problem: Civilization

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

We’ll need a miracle to save the world, and the only miracle we’re going to get is us. Right now, we—as in life on this planet we—are losing. That nobody wants to say this out loud doesn’t change its truth: we are losing, and badly.

For all the tireless marching, writing, petitioning, film-making, and purification of our lifestyles, how much destruction has actually—in the real world, not just our hearts and minds—been stopped?

We are losing. No one wants to say this out loud. Every impassioned conversation, book, and documentary film seems to follow the same wishful script: things are bad—okay, things are really bad—and while that’s certainly not good, it doesn’t change the fact that we are actually winning, that our individual actions are making a difference, that hearts and minds are changing, that we’re on the cusp of a great turning, that sustainability is upon us. All this whether the greedy or ignorant like it or not.

With our hands up in the air, who will do the work to make sure this future turns to reality? It’s easy to be optimistic in the cradle of privilege. It’s easier to look out the window and see winds of change when that window isn’t found in a sweatshop or prison complex. Those who feel firsthand the destruction of life—of democracy, community, freedom, landbase, and bodily integrity—do not have this luxury; they cannot pretend justice is now, or will be, prevailing when every day is testament of the opposite.

Many on the Left would call this cynicism. They would say it reflects a negative attitude. They would say negative attitudes don’t get us anywhere. They fail to mention what will.

The first step to not losing is to admit that we are. Cynicism is defined as a “feeling of distrust.” We would all agree that it is distrustful of humanity to imagine that we can do nothing. But it is also distrustful of our own collective power to lie about our dire situation and stake the future of the planet on mere hope and prayer.

We are losing. Most of the world’s old-growth forests, prairies, and large ocean fish have been wiped out. Indigenous species—including human beings—are under perpetual assault. Every river in the world is contaminated with carcinogens. 27 million people live in slave conditions. One in four women are raped and less than 10 in 100 perpetrators spend even one night in jail. The richest 1% own more wealth than the poorest 95%. One in nine African-American men are incarcerated. Nearly half a million farmers in India have committed suicide after having their livelihoods destroyed by multinational corporations. Every moment, every hour, every day, every year, it all gets worse.

In giving up the fantasies of some inevitable paradigm shift and subsequent global salvation—however good the fantasies may make us feel—another option reveals itself: actually changing the world. There is no shortcut to the nitty-gritty work of organizing, mobilizing, and taking action. Those not blinded by privilege know this all too well.

Despite intricate visions of what is to come, the activists so quick to employ lullabies in the place of concrete action are in fact doing a great disservice to the struggle. For those actively engaged in challenging unjust power certainly need encouragement, yes, and certainly need the assurance of knowing a better world is on the other side, yes, but they do not need to be lied to and they do not need reality watered down. Calling this a disservice is an understatement. Activists betray the oppressed they claim to stand for by promising a future they won’t act to create. They are witnessing a crime—be it land theft, rape, white supremacy, gay-bashing, or ecocide—and doing precisely nothing, safe in the excuse of a sweet, imagined tomorrow. It doesn’t get much more cynical than that.

We are losing. Where is the evidence showing this is not the case? The world isn’t dying from a lack of righteous rhetoric or symbolic action; it’s dying from the largest campaign of exploitation staged by the most unholy of alliances between the richest 1%. More, it’s dying because we aren’t doing anything about it. Setting good and pure thoughts aside, we haven’t even really begun to do anything about it.

Admitting to the vastness of the odds we face does not imply giving up. On the contrary, it is a sobering reassurance that there is much work to be done. It is an obligation for each of us to act. As Lierre Keith puts it, “any institution built by humans can be taken apart by humans.” We may be losing, but this does not mean we can’t start fighting back; it doesn’t mean there aren’t those who already have. Indeed, it is the underprivileged that lack the naivety—and, indeed, the cynicism—about the possibility of social change who have been most courageously engaged in it.

Ours is not a happy story. But while scene after scene depicts ever more loss, the ending has not yet been written. This is not cause for guessing what will happen. This is cause for fighting like hell to make sure it includes a living planet.

Members of the dominant culture—including the most progressive and well-meaning of us—teeter between cynicism and blind hope. When we feel despair, it’s all we can do to desperately explain it away by conceding to our own powerless: the problems are too big, so we may as well give up. On the flip side, we see a glimmer of humanity beneath the haze of apathy and conclude a revolution is nigh. Neither impulse serves our struggle.

Right now, we are losing. We need to not be so cynical as to pretend this loss is inevitable and not so idealistic as to pretend that we can wish our way to victory. Change happens when we fight for it. To begin this fight, we’ll have to at least be honest about our predicament: those on the side of a just, sustainable world are losing to those who would destroy it. This means we need to try harder.

It took five centuries for the Irish independence movement to break the stranglehold of British colonial rule. Every generation passed down the struggle to the next one; they passed down a culture of resistance and the understanding that this fight is a long haul. Other resistance movements have shared the same courage and determination, struggling for years and years to taste justice, persisting even when all seemed lost.

We too often forget our own history. Far from five centuries, today’s activists can barely manage five minutes without gratifying results. Worst of all, these (non-)actions reflect their unfounded expectations and, when change invariably doesn’t show, they give up.

Denying reality because it’s hard. Promising results without any plan of action to see them through. These are the qualities of children, not a strategy for success. As Frederick Douglass so bravely said, “If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men [and women] who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle.”

The rest of the world beckons activists of privilege to see past our blinders, past our cynical apathy, and open our hearts to reality, however uncomfortable it may be. It’s time to say this out loud: we are losing. It’s time to make a promise and dedicate our lives to seeing it through: we will win.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.

A Swedish translation of this article is available at: http://djupgron.wordpress.com/2013/06/10/berattigad-till-forlust/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 7, 2013 | Gender

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

What makes a radical a radical is a willingness to look honestly and critically at power; more specifically, imbalances of power. We ask: Why does one group have more power than another? Why can one group harm another with impunity? Why is one group free while another is not? These kinds of questions have long been used by radicals to identify oppression and take action against it. The process has seemed both straight-forward and effective—until applied to the oppression of women.

As persistently as the radical Left has put names to the many rotten manifestations of the dominant culture, they have ignored, downplayed, and denied the one called patriarchy. While it’s generally understood that racism equals terror for people of color, that heterosexism equals terror for lesbians and gay men, that colonialism equals terror for traditional and indigenous communities, that capitalism equals terror for the global poor, and that industrialism equals terror for the earth, radicals somehow just can’t get that patriarchy equals terror for women. If it ever comes up at all, the oppression of women is diluted to the point of sounding more like a bunch of isolated, temporary, uncomfortable circumstances than what it really is: an ongoing war against the freedom, equality, and human rights of more than half the world’s population.

The degree to which sexism, male privilege, and patriarchy are not addressed amongst radicals is the degree to which they plague us. It’s a vicious cycle: as men on the radical Left repress feminism, they forcibly silence concerns about unjust male power within the radical Left, and thus solidify dominance over political movements which will likely never again be able to overcome unjust male power.

Patriarchy run amok is the enemy of truly radical activism. There can be no liberation in the world, if those claiming to fight for it aren’t ready for the liberation of women in their own ranks. As my dear neighbor says, “There’s nothing progressive about treating women like dirt; that’s what’s happening already.”

Maybe some of these men don’t see their privilege. Or maybe they see it fine and feel entitled to it. In either case, most are comfortable with the status afforded to them based on their sex, both in society and social movements. Men sit atop a hierarchy with half of humanity beneath us, forcibly there for us to talk at, dump undesirable work on, and use for sex. This reality doesn’t simply disappear by calling yourself “radical.” Indeed, any radical who doesn’t see this—never mind challenge and stop it—isn’t worth the name.

Too often, so-called radical politics are really just men’s politics. Righteous declarations about resistance to all forms of domination aside, men cleverly manipulate movements to stifle anything threatening our own power and privilege—including women.

Within this rigged game, radical men and the political groups they control are more than happy to address patriarchy; as long as they control the debate, it’s no sweat. With a snap of the fingers, the fangs of feminism disappear. Men are oppressed too, they plea. Things aren’t as bad as they seem, we learn. Women are liberated, they demand. And somehow, with all traces of common sense thrown to the wind, the radical Left as a whole eats the lies and turns them into political policy.

If only radicals would understand gender like they do race and class. It seems so obvious: gender, like race and like class, is a social construct that justifies the oppression of one group by another. That’s it. But ask most—though, especially men—on the radical Left about gender, and prepare for the bizarre. In taking power entirely out of the equation, they claim gender is really just a spectrum to choose from, or something innate and therefore inevitable, or even a metaphorical and playful war between the sexes.

In actual reality, gender is none of these things. It’s not a choice; women don’t have the power to decide to not be treated as they will within a woman-hating culture. It’s not natural; biology is an excuse used to justify the ideology of patriarchy. It’s not fun and the war against women is not metaphor. Assault, slavery, exploitation, trafficking, and second-class status are daily fare for women, and gender is the excuse. You don’t accept or play with a hierarchy; you dismantle it. Radicals should know this.

Gender is a terrible lie with the realest of consequences. It starts with human beings and socializes—read: deforms—them into classes of people called “men” and “women”. Further, it claims that men and women each possess an innate set of personal habits—and worth—termed masculinity and femininity, or “maleness” and “femaleness”. Men learn domination and women learn submission. Patriarchy thrives.

This social construction is the same with race and class. The difference is that radicals would have no problem—we hope—seeing through the idea of some innate (or chosen) “blackness” or “poorness”. No human being is born on the bottom of a hierarchy; women, like the global poor and people of color, are forced there.

Power isn’t pulled from thin air; it is taken from the powerless. If men have power, women don’t.

Masculinity is defined by the violation of boundaries. No longer simply human, men use sheer military-style force to get what they want, to satisfy an insatiable ego. Men prove we are real men by making others—often women—bend, and ultimately break, to our wills.

Male privilege is the grand rationalization, the justification of unjust power that we men try to make ourselves, and everyone else, believe. The lesson is that masculinity is normal and men are absolved from accountability; that men know best and are always right. The hierarchy thus becomes inevitable, resistance seeming like an utter waste of time.

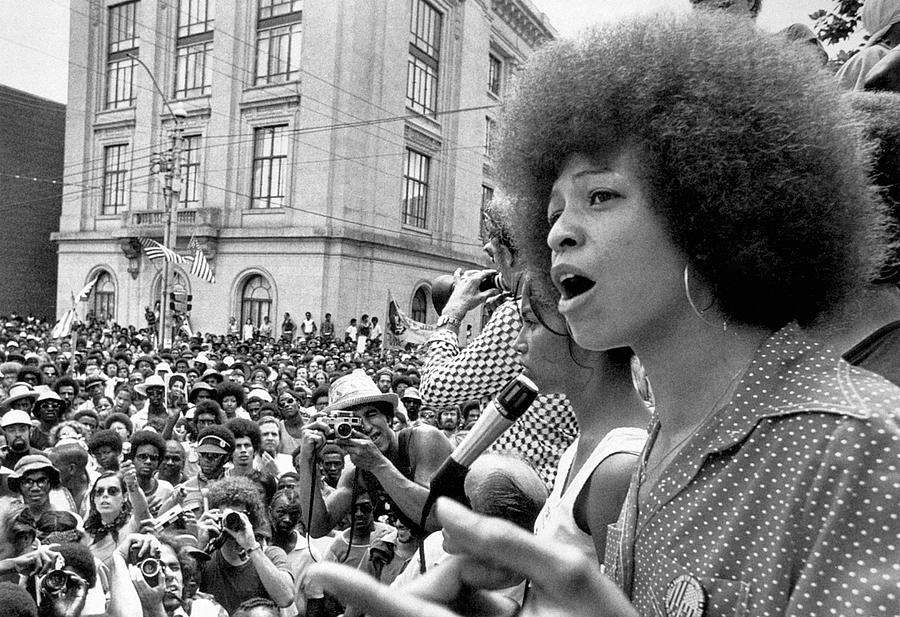

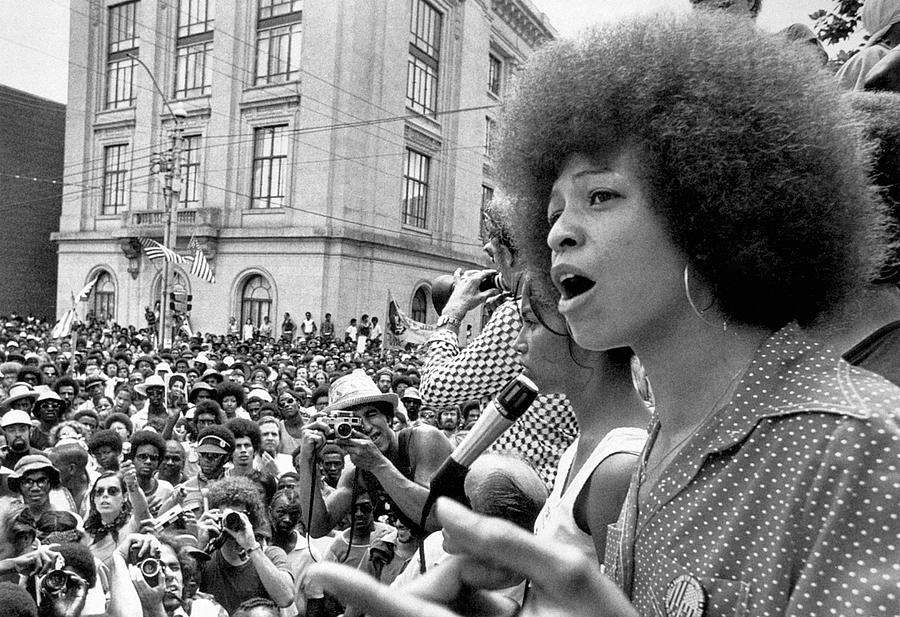

Feminism is the other side of the war. It is, in the brave words of Andrea Dworkin, “the political practice of fighting male supremacy in behalf of women as a class.” This commitment is radical politics at its most honest, which is precisely why the male-dominated radical Left stands in its way.

Feminism explodes the lies that make patriarchy seem benign. It demands full humanity for women and is willing to struggle to achieve it.

When we’re honest about the breadth of damage that gender does to women, we see the breadth of action necessary to get us from here to justice. Sexism is clearly not a mere uncomfortable circumstance, amendable by attitude alone. Rape, pornography, humiliation, trafficking, and reproductive slavery are anything but mental events. If the radical Left would look honestly at these atrocities—let alone, not participate in them—we’d know what to do: organize and resist.

Instead, radicals call it “sexual liberation” and choose to celebrate it—a heart-breaking legacy with its roots in patriarchy and history in the social movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s. If a woman can choose to fuck, they claim, she must be free.

Choice, however, is only as meaningful as what there is to choose from. Women can choose between invisibility and sexual exploitation; they can choose between poverty and sexual exploitation; they can choose between death and sexual exploitation. I’d trust radicals to call bluff here if the opposite—collusion with the sexual exploitation of women—hadn’t been confirmed over and over again.

Feminism strikes a nerve. When men don’t get our way, backlash isn’t too far behind. Feminists face it from all directions. It seems anarchists, communists, sexual libertarians, men’s rights activists, and right-wingers can agree on at least one thing: the sanctity of male power. Men, along with whatever groups they dominate, come out in full force to put women back in place, whether through slander, censorship, threats, or physical violence.

There’s been little reason for women to count the male-dominated radical Left as anything resembling an ally. On the contrary, radicals seem ever willing to lend a hand to the other side. Take just this past week for example, when one environmentalist woman was barred from speaking at a university’s Earth Day event because she happened to also be a feminist; and when a decades-old women’s music festival was publicly ostracized for not letting men in; and when a venue slated to host one of the world’s only radical feminist conferences is considering reneging on the agreement after ongoing harassment from radical and conservative men, alike.

But if it’s not blunt retaliation men use to silence feminist women, its outright lies. The most common one is that men are, in fact, oppressed too. The radical Left has taken the bait. In the face of story after story depicting the terror waged daily against women, radicals want to know one thing: what about the men?

Of course men experience oppression—but not because we are men. Patriarchy means that, no matter the individual man, he will be treated as more of a human being than a woman would within the same circumstances. Men may be subjugated in a myriad of ways—each abhorrent and deserving of resistance in its own right—but not because we were born not female. Indeed, even the most otherwise oppressed or egalitarian or radical men have the capacity to use their power as men to hurt women. We needn’t ignore one injustice to see another.

If we, as radicals, are to live up to our name and traditions by getting to the roots of unjust power, we need to reject and combat patriarchy on all counts, at every level. Every time we allow men to wield power over women, we help the enemy.

If radical men want to fight the power, as many claim, we can start with men’s power over women. We can resist domination in all its manifestations; even—or especially—when doing so threatens our own privilege; even when it means changing who we are.

There’s no revolution and no justice without freedom for women. Patriarchy is destroying our social movements as surely as it’s destroying the lives of women and as surely as it’s destroying the planet. As musician Ani DiFranco sings, “The road to ruin is paved in patriarchy.” The road to revolution, on the other hand, is paved in feminism. As radicals, the choice is up to us: ruin or revolution?

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance. He can be contacted at benbarker@riseup.net.

A Swedish translation of this article is available at: http://djupgron.wordpress.com/2013/05/12/den-sexistiska-radikala-vanstern-versus-kvinnor/

A French translation of this article is available at: http://coll.lib.antisexiste.free.fr/CLAS.html

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 1, 2013 | Movement Building & Support, Strategy & Analysis

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

Do you believe in a better world? Do you believe in one without the torture of poverty and slavery; without hierarchies based on dominance; without a dying planet? If you do believe in this world, what are you willing to do to help bring it about?

I know many who yearn for justice, but far fewer with any kind of plan for achieving it. There’s no lack of morality in this equation, just of strategy and, perhaps, courage.

Every movement for social change has understood that when a system of law is corrupt, we must turn instead to the laws of the universe: human rights, the living land, justice. These movements are always deemed radical—and that’s because they are. Hope and prayers do not alone work to change the world. We’re going to have to fight for it.

All your heroes of the past knew this. Those who won civil rights knew it. Those who won women’s suffrage knew it. Those who abolished slavery knew it. Those who freed India from colonial rule knew it.

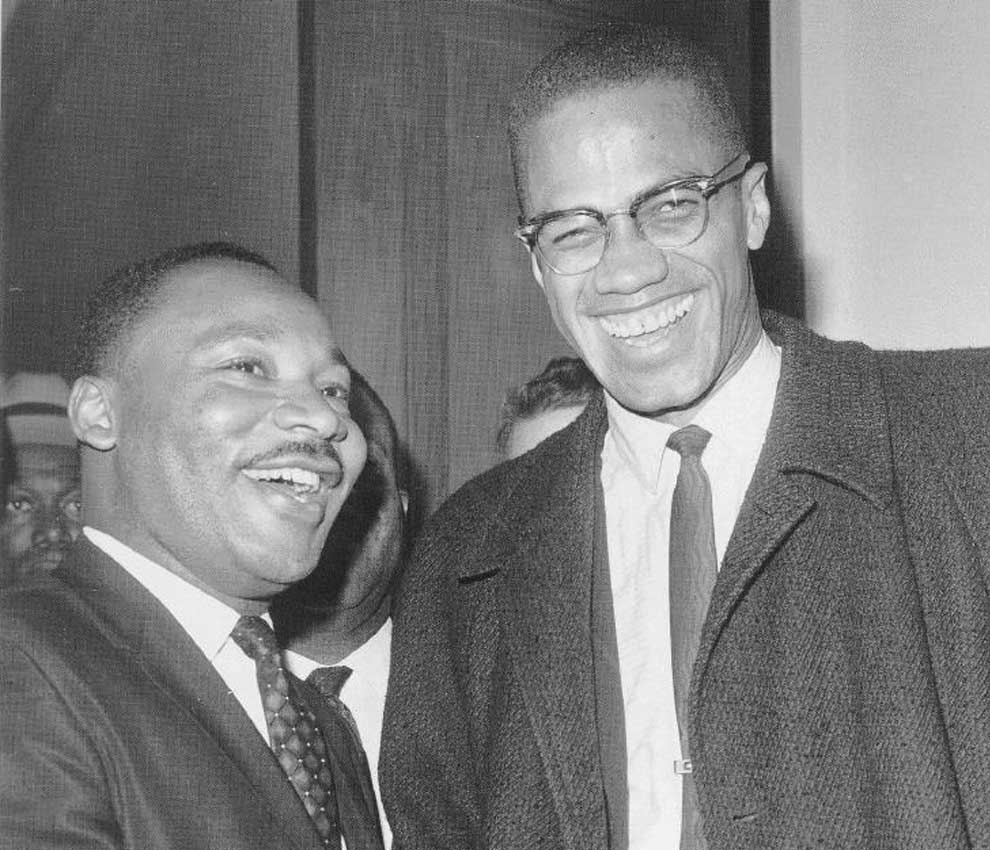

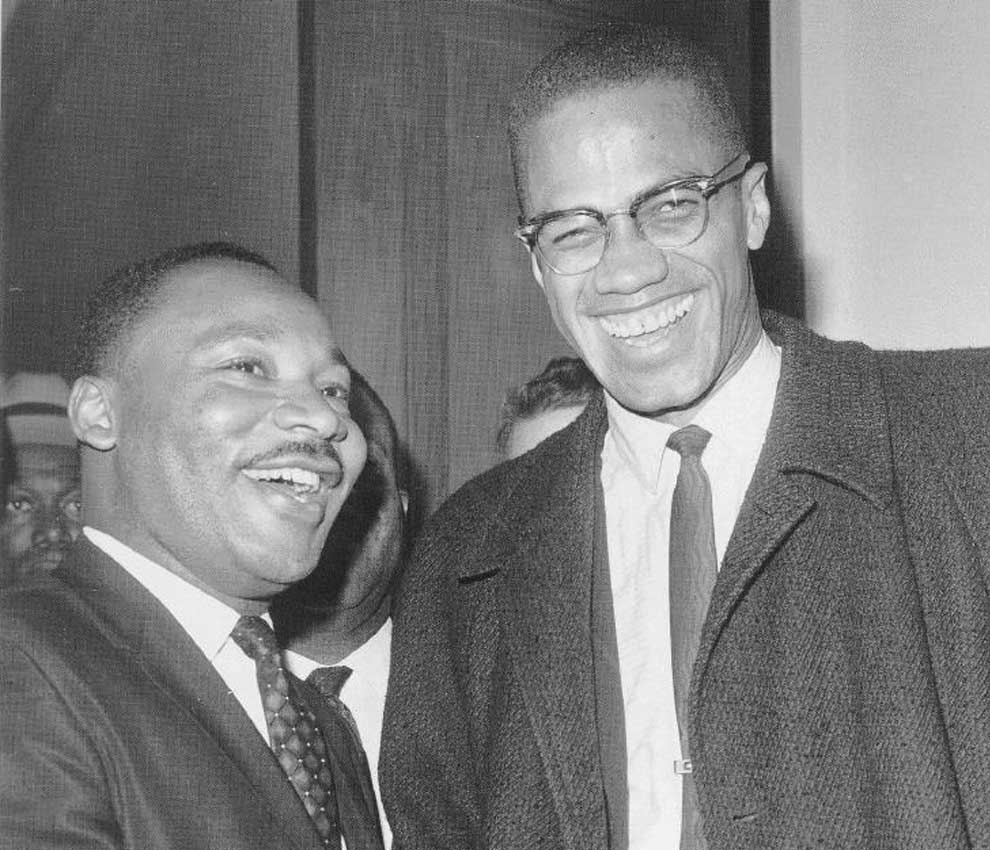

Martin Luther King, Jr. clearly understood this. He said, “Freedom is never given to anybody, for the oppressor has you in domination because he plans to keep you there, and he never voluntarily gives it up. And that is where the strong resistance comes. We’ve got to keep on keeping on, in order to gain freedom. It is not done voluntarily, but it is done through the pressure that comes about from people who are oppressed. Privileged classes never give up their privileges without strong resistance.”

All movements striking at the roots of social problems were—and still are—radical by default.

There’s no shortage of issues that need tackling today. Pick your favorite atrocity: dying oceans, species extinction, deforestation, climate chaos, pollution, violence against women, militarism, white supremacy, poverty, colonialism, homophobia, slavery, government corruption. The hard reality is that the world and all that makes life worth living is under attack—and we’re losing the battle. Everything keeps getting worse and our standards for success keep getting lowered. Never has there been a more critical time for those who want a better world to rise and make it happen. So what’s stopping us?

Of course there are vast and powerful entities wholly invested in and mercilessly guarding the way things are. This is an old story; we’re Margaret Mead’s small group of thoughtful, committed citizens taking on a giant. But in reality, we’re not even there yet. No, we’re still struggling to find unity amongst ourselves, to gather the people necessary to begin making any change at all.

It’s long past time to be forthright about what divides us as activists. Most all of us want to see the same outcome—a living planet, flourishing human communities—but we stumble on how to get there. Sure, some things we just won’t agree on, and that’s perfectly fine. But with the stakes so high, are we willing to forfeit all possibility of effectiveness because we can’t find a way to get along?

Let’s talk about our differences so we can better find our common ground. Writer Lierre Keith has investigated the history of social movements and emerged with much of the work done for us. She suggests there are two major currents amongst activists: liberals and radicals. This is not a dichotomy: like reform and revolution, both liberals and radicals have been necessary and complimentary to each other. The key is balance and respect for various approaches to the same problems.

The first difference between radicals and liberals is how we view individuals. Radicals see society as made of groups or classes; individual people share common clause based on shared circumstances and goals. Liberals, on the other hand, see individuals as just that; each person is distinct from another. The “working class”, for example, was a radical concept which liberals have largely removed from their discourse.

Next is how social change happens. Liberals lend their energy to ideals and attitudes, certain that change will come one heart and mind at a time. Institutions are the targets of radicals, though, with old corrupt ones sought to be dismantled and replaced with just, sustainable, new ones. If Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement would have focused solely on convincing whites that blacks aren’t inferior, they would have been taking the liberal route. If they would have focused solely on defeating racist laws, they would have been taking the radical route. History suggests that it was both that got the job done.

A final difference centers on justice and what we think it looks like. Radicals tend to measure justice by long-term material conditions—a lack of oppression and destruction in everyday life, now and forever. Morality is predetermined for the liberals, with the law or broader society acting as judge. Any win in the realm of free speech, for example, might look like a step in the right direction to the liberal perspective, whereas radicals might be more concerned with eliminating hate speech (and groups), whether or not it is legally permissible.

Despite the distinctions, effective activism hinges on understanding power and how it works. Wherever we may fall on the spectrum, we must keep our eyes on power: who has it, how it’s being used, and how it can be transferred from the hands of the powerful to the hands of the powerless. There is no way to talk about social change without talking about power.

Again, all throughout history liberals and radicals have employed complimentary strategies to make tangible differences in the world. We may feel uncomfortable working with each other, but it’s either that or an increasingly ruined world. The ethical choice should be clear.

What liberals need to understand is that any efforts challenging systems of power are and will be seen as radical. There’s just no way around it and forging distance from radical counterparts is not only useless, but a betrayal of freedom-fighters before us. We need to remember that Rosa Parks’ hero was Malcolm X. We need to remember that Gandhi was successful because he was easier to negotiate with than Bhagat Singh’s militants. Neutrality is complicity and it’s time to take sides: one hand is the small group of capitalist monsters profiting off of misery and on the other is anyone willing to resist injustice.

Recently, I had a conversation with a member of the Democratic Party which highlights how far from solidarity many liberals have strayed. Upon meeting, he asked what I did. “I’m a writer,” I said. About what, he wondered? “Radical social change,” I told him. And the next fifteen minutes, up until the point I politely left, saw him adamantly discouraging me from using such a confrontational and extremist term as “radical.” My claims that this desperate time calls for radical responses fell on deaf ears, because how desperate can anything be with a Democrat in the White House? In hindsight, I wish I would’ve reminded him just how radical the movements have been that are now allowing for black, female, and homosexual candidates from his Party to get in office.

What radicals need to understand is that what is most militant is not always what is right, both in terms of strategy and morality. And sometimes it is. Power only changes by force, but force can take many different forms. Suffragists lobbied and campaigned for women to get the vote, but when that wasn’t working, they added sabotage to their arsenal. Simultaneously used, their tactics proved part of an ultimately successful strategy. Both approaches were radical because they applied force, but they were employed in very specific times and contexts. Strategy allows us to choose between tactics with a lens of pragmatism rather than by whim of emotion. Whatever actions are taken, they must be well thought out and conducted with discipline.

Too many radicals today fall into the trap of black-and-white thinking. They see bad institutions and therefore all institutions are bad. They see useless reforms and therefore all reforms are useless. They see poor leadership, and therefore no leadership is better.

Radical or liberal, we really need it all. We need the community organizers, the gardeners, the healers, the warriors, and the artists. Most of all, we need to each other’s work as necessary pieces of the larger struggle.

Regardless of our route, activists need to always remember the world we’re working towards. Solutions will come only after we honestly name the problems. This means we cannot look away from the severity of the situation, even if it doesn’t make us feel good. Social change is about social change and not about any individual’s emotional state. Suffering is real and it beckons us to fashion adequate responses.

Changing the world means naming the one we’re presently stuck with. It’s time to say this out loud: the problems we face are systemic, not random; they are symptoms of a social and economic arrangement of power. I call that arrangement industrial capitalism. You may call it what you like. What’s important is that we all understand that there is no future in the way things are.

Liberals, radicals, and anyone working towards a more just and sustainable world cannot continue to spend so much time condemning each other’s approaches. There’s a name for this destructive tendency: horizontal hostility. And unless we want to in-fight to the end of the world, it has to stop.

Success will be the forging of a culture of resistance strong and vibrant enough to take apart this society and build a new one. This means vast networks of communities of people supporting each other’s efforts towards a common goal. It means the artists support the warriors who support the healers who support the gardeners who support the community organizers who support the warriors. Not all in a culture of resistance need agree on everything; we just need to pledge that we won’t turn on our own in the heat of the struggle.

For every year, every day, and every moment we don’t act strategically and decisively, another person of color is terrorized by white police officers, another woman is violated by men, another indigenous culture is stamped out, another species is added to the extinction list, the health of human community and the entire planet accelerates in decline.

Those with fire and love in their hearts, those who live by moral obligation, know that the time to act is now. So the question becomes: will you join us in finally and totally changing this world. Is your privilege and comfort more important than justice, or will you join us? Are your ideals more important than the hard truth, or will you join us?

If you want a better world, what are you waiting for? Find your allies, work out your differences, and get down to business.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 1, 2013 | Alienation & Mental Health

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

“There is a problem. It’s a big problem. It’s not just the kids in the inner city. It’s the average middle-class family dealing with this and suffering huge losses.” The problem is heroin. The voice quoted here belongs to a local parent who just lost two sons after they overdosed on the drug.

I live in a relatively small, mostly white, and definitely conservative Midwestern city where this just keeps happening: kids are dying. Heroin has been seeping into my community for years now. Combined with an already existing culture of heavy drinking, and the addiction, poverty, and violence that almost always accompanies substance use and abuse, the result should be obvious: a new twenty-something-year-old face in the obituaries every week. They didn’t die because they were simply irresponsible or reckless; this crisis is built in to the dominant culture, and nothing will get better until this culture is changed.

We live in a society that values money above all else. Money comes before education, before healthcare, before children, before community. Decisions affecting all of us are made according to profit motive rather than human need. On every level, capitalism systematically exploits and destroys healthy communities.

The backdrop to this local heroin crisis is a repressive city that does little to serve young people or anyone besides the rich elites who run it. Social programs and initiatives are relatively nonexistent. Cafes, music venues, and other social spaces are denied funding so that they usually have an expiration date of less than a year. We’re left with only a few options: get a job, get high, or plan to move away. The gate-keepers of this community enforce a terrible double-standard: they won’t talk about their kids who are shooting up and dying, but they also won’t provide (or allow) an alternative.

Speaking of no alternatives, about one-third of this country’s population is living below the poverty line or near it. The rich keep getting richer and the poor keep getting poorer. The places hit first and hardest are what Chris Hedges calls “sacrifice zones.” These are the colonies of empire—the ghettos, the barrios, and the reservations. Like the grieving parent alluded, it’s not uncommon that “kids in the inner city” die young, because those communities were gutted—flooded with alcohol, gentrified, and stripped of social services—long ago. But now, the pillaging has come around full circle to take even the children of the “average middle class family,” the children of the elites.

The story is the same everywhere: when there’s nothing to live for, there’s no reason to care about living. Hopelessness is universal.

Last night I had a conversation with one of my peers who quickly moved from this town as soon as she was of age. In just one year, 12 of her hometown friends have died from heroin or drunk driving.

My childhood best friend, 20 years old, overdosed on heroin. A year later, his friend, also 20 years old, overdosed on heroin. A person I had a crush on in the 8th grade recently died after driving drunk. A person I used to go skateboarding with in high school recently died after driving drunk and smashing his car into a brick wall. I wish I couldn’t, but I could go on and on.

My heart breaks a little more every time a young person’s life is so needlessly taken because of the sad, sorry culture built by generations before us. From Palestinian and Pakistani children bombed to death, to the guns fired by gang kids, to the unheard cries of suicidal victims of bullying, to the cities mourning too many heroin-related deaths to count—the young did not design this cruelty, nor do we have much of a say in changing it.

We have only two choices: adapt or die.

Some people can’t adapt. They were born into a body that simply doesn’t allow it—one that is female, one that is not white. Even if members of historically oppressed classes want to adapt to this culture, they are always denied the status of full human beings. But the choice was never meaningful for any of us; you can only adapt to drinking poison for so long before it kills you as sure as it does anyone else.

Adapt or die. Deep in our hearts, young people understand the profound sickness we are being socialized into. There’s little to make us feel alive in this routine of school, work, die. Save suicide, how do you cope with that? Welcome to addiction. It can be drugs, alcohol, money, sex, or anything that will numb the pain of being trapped in desperation. We’re floating in a sea of despair, struggling just to keep our heads above the water of self-destruction, but all the while sinking into a pit of hopelessness and forgetting what it means to feel alive. Eventually, as was true for my friends no longer living, a person just gives up.

Before fizzling out, many will grasp for control by abusing whoever is nearby. But perpetuating cruelty will not save you from emptiness. Breaking boundaries is a habit that can only end in overdoses, alcohol poisoning, bullet wounds, and a short life devoid of anything resembling love.

Adapt or die. The only way out of a double-bind is to tear it down and start over. Conformity will not get us anywhere. There’s no shortcut to a life of meaning and integrity. And to get there, we have to choose not to adapt, not to die, but instead to resist. We need take back the humanity we’ve been denied.

Capitalism requires obedience. It needs good workers, good consumers, and good citizens, who have submitted our own wills and desires for the sake of “the way things are.” Sure, we might get a little rowdy once in a while, but as long as we don’t fundamentally challenge the system in which we’re trapped, nothing changes. Dead kids are of no consequence as long as they remain powerless to the very end.

Many from generations before us have chosen to resist this corrupt arrangement. But far too many more have not; they accepted the system as their personal savior, always willing to defend their conditions and never raise a finger or mutter a word in defiance. The result is a world of expanding sacrifice zones, which have now become so large as to subsume the youth of everywhere.

When asked why she was protesting the liquor barons preying on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Lakota activist Olowan Martinez said, “Today I defend the minds of our relatives. Alcohol is a plague; it’s a disease; it’s an infection that causes our young people to kill themselves, to harm each other, to harm their own. We need to stop it before it’s too late. We came here to save the minds and mentality of our own nation.”

Young people today have no real chance of a future with good education, decent housing, and enough food or water. Moreover, we have no real chance of becoming who we are and who we truly want to be, no real chance of claiming the desires and dreams that are our birthright as sentient beings. The planet is burning, human societies are collapsing, and those in power are profiting from it all. It is our generation and those to come after that inherit this mess. We are living out an endgame and everything is at stake: life and all that makes life worth living.

Getting high will not make the horrors disappear. But until the horrors disappear, we can be sure that kids will keep getting high.

The youth have the most to lose, but we also have the most potential to turn things around. We can stop giving up our souls and, ultimately, our bodies, to this culture of despair. We can join with young people everywhere—from Palestine to Chicago, from Newtown to Pine Ridge—to let the powerful know that we will not be sacrificed for their profit. We will put down the drugs and put up our clenched fists. We will say enough is enough. We will not adapt and we will not die.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 1, 2013 | Movement Building & Support, Rape Culture

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

There’s no such thing as a functioning group of human beings existing without leadership or structure. That sentiment, while exalted by many on the radical Left, is a fallacy. Whether or not we want it to be true, human beings are by nature social creatures and we learn by the example of others, which is to say we learn from those we look up to and from the customs of the culture we live in. Leadership and structure are inevitable. The only questions are by who? and how?

Sure, radicals can reject this notion and operate as if it didn’t exist—it’s what many are already doing. But, all the while, our groups still move in particular directions, and it’s the members that take them there. Those who wish to prohibit leadership and formal structure are really just spawning informal versions of both, with themselves at the helm of control.

There’s a long history of this. From the anti-war movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s to the anarchists and Occupy movement of today, “leaderlessness” is almost taken as a given; it’s praised as an obvious first step in challenging power inside and out. Again and again, however, we see this paradox’s predictable outcome: when structure is not explicit, it takes its own form—one usually shaped by those most willing to dominate the group.

This was the lesson of the classic Leftist essay, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” in which author Jo Freeman argues that, as movements “move from criticizing society to changing society,” they need to honestly and openly address how they will organize themselves. “[T]he idea of ‘structurelessness,’” she writes, “does not prevent the formation of informal structures, but only formal ones.” So in all the backlash against formality, activists are only serving to undermine their own supposed ethics by contributing to unspoken rules and hierarchy.

Intentional organization may or may not lead to the egalitarian, functioning movements we desire—there are clear cases of both the success and failure of formally structured groups. Done well, however, structure can provide a means of accountability between members that their structureless counterparts inherently lack. In the best case scenario, the group’s expectations and rules (I hear the shrieking of purists already) are explicit and accessible to everyone, allowing leaders and followers alike to keep each other in check.

“A ‘laissez-faire’ group is about as realistic as a ‘laissez-faire’ society,” Freeman writes. “The idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.” Too frequently the backlash against group structure is a deliberate attempt on the part of a few to maintain invisible and unquestioned authority over a group’s ideas and direction. So begins elitism.

Jo Freeman claims that elitism was possibly the most “abused word” in the movements of her time and I’d say the same is true today. The term is too often thrown out thoughtlessly and on any occasion of mere disagreement. It becomes a tool for those who want to destroy potential for leadership; public attention of any kind is in this case conflated with power-grabbing and exclusivity, with elitism.

Still, elitism is very real and has very real consequences. Freeman writes, “Correctly, an elite refers to a small group of people who have power over a larger group of which they are part, usually without the direct responsibility to that larger group, and often without their knowledge or consent.”

There are numerous myths about what constitutes elitism: public notoriety, social popularity, the inclination to lead. But none of these are sufficient descriptors of the phenomenon. More than anything, accusing one of being an elite based on such qualities speaks to the paranoid and destructive tendencies of the accuser. As Freeman writes, “Elites are not conspiracies. Seldom does a small group of people get together and try to take over a larger group for its own ends.” She continues, “Elites are nothing more and nothing less than a group of friends who also happen to participate in the same political activities.”

Not surprisingly, these friends will—sometimes unthinkingly, sometimes intentionally—maintain a hegemony within the group they are part of by agreeing with and defending each other’s ideas almost automatically. Those on the outside of the elite group are simply ignored if unable to be persuaded. Their approval, says Freeman, “is not necessary for making a decision; however it is necessary for the ‘outs’ to stay on good terms with thin ‘ins’.” She continues, “Of course the lines are not as sharp . . . . But they are discernible, and they do have their effect. Once one knows with whom it is important to check before a decision is made, and whose approval is the stamp of acceptance, one knows who is running things.”

Unspoken standards define who is or is not entitled to elite status. And they have changed only slightly since Jo Freeman brought activist elitism under the spotlight; most have endured the test of time, destroying our movements and inflicting pain on many genuine individuals. Such standards include: middle-to-upper-class background, being Queer, being straight, being college-educated, being “hip”, not being too “hip”, being nice, not being too nice, holding a certain political line, dressing traditionally, dressing anti-traditionally, not being too young, not being too old and of course, being a heterosexual white male. As Freeman notes, these standards have nothing to do with one’s “competence, dedication . . . . talents or potential contribution to the movement.” They are all about selecting friends and contribute little to building functioning community.

Of course friendships are crucial to resistance; they represent trust and perseverance between freedom fighters, an absolutely necessary quality for the high-pressure nature of taking on systems of power. But basing our activist relationships on who we pick as friends—those who pass the test of those arbitrary standards—creates circumstances ripe for nasty division and social competition. And, writes Jo Freeman, “[O]nly unstructured groups are totally governed by them. When informal elites are combined with a myth of ‘structurelessness,’ there can be no attempt to put limits on the use of power.” Friend groups must confront this potential disaster by being honest and upfront about their relationship to one another. Further, they should advocate for transparency and processes of accountability. It is up to such friend groups to ensure that they do not succumb to elitism.

The same transparency and accountability must apply to leaders and spokespeople. It is not entirely the fault of those who fill those roles when they are viewed as insular gate-keepers of the movement. Without a forthright decision-making process, there’s no way for other members to formally ask to take the lead on a project or to publicly represent the group at any given time. Yet, some are naturally inclined to take initiative, and because they are not explicitly selected by their comrades to do so, they become resented and, too often, ousted.

And what does this accomplish? The group is left without energy to move it forward and the activists kicked out are now even less accountable to the movement of which they were once part. This purging has no future. Instead, our movements should be open and honest about what we want to convey to the public, who will say it, and when. If anyone is to be ejected, it should be because they consciously betrayed the trust of their comrades, not because they took initiative.

Unstructured groups may prove very effective in encouraging people to talk about their lives; not so much for getting things done. This is true from the micro to the macro; whether we’re talking about facilitating meetings, getting food to frontline warriors, or planning a revolution. Says Freeman, “Unless their mode of operation changes, groups flounder at the point where people tire of ‘just talking’ and want to do something more . . . . The informal structure is rarely together enough or in touch enough with the people to be able to operate effectively. So the movement generates much emotion and few results.”

Much emotion and few results. This is the standard mode of radical subcultures.

Structurelessness may be a romantic idea, but it does not work. The floors still need sweeping, the food still needs cooking, and if tasks aren’t explicitly assigned, they will, without fail, implicitly fall on the shoulders of a couple tired leaders. Frontline combatants cannot afford that sort of confusion; they need a detailed plan of action. Going with the flow might work fine for a potluck, but in a serious movement the flow will only lead activists into dangerous situations, wasted time, and compromised actions.

Jo Freeman continues: “When a group has no specific task . . . . the people in it turn their energies to controlling others in the group.” She goes on, “Able people with time on their hands and a need to justify their coming together put their efforts into personal control, and spend their time criticising the personalities of other members in the group. Infighting and personal power games rule the day.” The forecast was dead-on.

What can we do to save our communities and movements (or even build them in the first place)? The answer seems crazy, but really it’s simple: work together. In this age of immense individualism and pettiness, it may sound impossible, but I truly believe that, despite a few (often insignificant) differences, activists really can find common ground and tolerate one another long enough to make some tangible political gains. Sometimes, all it takes is having something to do. As Freeman notes, “When a group is involved in a task, people learn to get along with others as they are and to subsume dislikes for the sake of the larger goals. There are limits placed on the compulsion to remould every person into our image of what they should be.”

By adhering to an ethic (or is it non-ethic?) of leaderlessness and structurelessness, we set our movements up for failure. The longer groups continue on such a basis (or is it non-basis?), the less likely the pieces will be able to be picked up after the project inevitably collapses. And, as Freeman points out, “It is those groups which are in greatest need of structure that are often least capable of creating it.” Tedious and unglamorous as the work may be, we desperately need to learn to develop structure from the beginning, rather than hoping and praying it will come together organically. The fact is it almost never does and the result is a take-over by elitists who only run movements into the ground.

Structuring groups is hard work. Without structure, our energy is diffuse and largely ineffective. But bad structure almost always leads to crisis and, like a building that grows and grows until it all comes crumbling down, it often does more damage to those involved than it would have had there been no structure from the outset. And yet, the resistance movements this world needs require a means to stay organized and effective.

Here’s a story from just this week: “[Britain’s] largest revolutionary organization has been shaken by the most severe crisis in its history, stemming from the failure of its leadership to properly respond to rape and sexual harassment allegations made against a leading member, and, in turn, from attempts to stifle discussion of this failure and its consequences.” One leading member noted that “the party’s internal structures don’t have the capacity to judge cases of rape.” Need I say that radical groups desperately need this capacity? If we don’t know how to handle sexual assault—or any sexism, for that matter—when it arises, if we don’t know how to kick out rapists from our groups, how are we supposed to have the capacity to work together in dismantling vast systems of power?

What’s the alternative? In “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” Jo Freeman offers seven “principles of democratic structuring as solutions that are just as applicable now was they were then. The first is delegation: it should be explicit who is responsible for what and how and when they will do the task. Further, such delegates must remain responsible to the larger group. Accountability ensures that the group’s will is being carried out by individual members.

Next is the distribution of decision-making power among as many members as is reasonably possible. Following that, rotating the tasks prevents certain responsibilities from being solely in the domain of an individual or small group who may come to see it as their “property.” Allocation of these tasks should be based on logical and fair criteria; not because someone is or is not liked, but because they display the ability, interest, and responsibility necessary to do the job well. Next, information should be diffused and accessible to everyone as frequently as possible. And lastly, everyone should have equal access to group resources, and individuals should be willing and ready to share their skills with one another.

Such principles are easy to write or speak about, but much harder to put into practice. People without much power over this society are prone to grasp for it when they get a taste, but too often they are just stealing from yet another powerless person. Writes Florynce Kennedy: “They know best two positions. Somebody’s foot on their neck or their foot on somebody’s neck.” So, it is imperative that we safeguard against the pitfalls of horizontal hostility, especially as we work to create fair and effective structure. Leaders must be held accountable for the power they have. At the same token, we can no longer allow leadership to be systematically stomped out. We can no longer allow the tyranny of structurelessness.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.